Introduction

Sixty-seven years ago, the Allies landed in Normandy. In the wake of the British, Canadians and Americans followed the French, Dutch, Polish and Belgians. This is the story of how The Piron Brigade (1) entered into the history books of the Second World War.

Why talk about this in the pages of the Bulletin Segnia [A newsletter of the Belgian Cercle d'histoire et d'archéologie, Segnia]? The photograph of the author of this article explains it. He was a lover of good beer. He was a brewer himself and a long-time friend of Christian Bauweraerts, who relocated to Houffalize, and with Pierre Gobron, established the Achouffe Brewery for which Houffalize itself has come to be well-known. It was through Christian that Modeste’s manuscript has reached us.

In 1969, at an Antwerp Rotary meeting, Modeste had presented a brief account of his years in uniform while in England and in the area between Normandy and the Meuse River. That same year, his experiences were published in the Club Bulletin. He painted a picture of the less than ideal conditions in which a group of Belgians, who came from all walks of life, prepared for their engagement in the theatre of operations, without showcasing his personal contributions. Therefore, it seemed useful for us to pay tribute to these men who found the spirit to fight for their freedom and that of their countrymen.

The Author

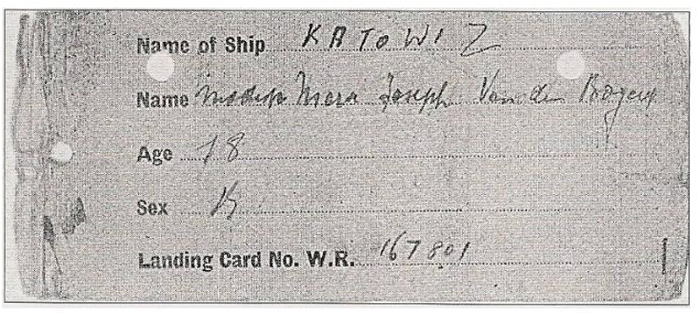

When war was declared, Modeste van den Bogaert was a student at the College of the Jesuits in Antwerp. He was drafted by the C.R.A.B. and was required to report to the Recruitment Center in Roeselare. As chaos reigned everywhere, he was first sent to Poperinge and from there to an area south of the Somme. His brother Étienne accompanied him. The movement of troops was done on bicycle. They were pushed back at the French border three times, before successfully crossing at the beaches of De Panne, Belgium. At Abbeville, France, they found themselves face-to-face with German Panzers. They then went to Calais where they boarded a Polish ship, called Katowiz after which they lifted anchor for the destination of Bordeaux.

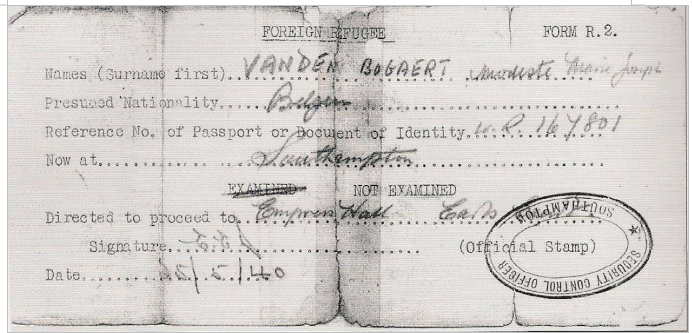

The British Admiralty decided otherwise, and after three days circling at sea, they instead landed at Southampton, England. Here they submitted to several identity checks. Modeste passed before two Scotland Yard police officers who asked him for the names of his parents and the occupation of his father. "A Brewer", Modeste replied. The quick follow up question was: "Which Brewery?", and just as quickly, Modeste’s response was: "De Koninck". One of the men from Scotland Yard replied: "What is the name of the cafe in front of the brewery?" Obviously, Modeste knew the answer: "De Pelgrim", which opened a big smile on the mouth of the inquisitor. He and his brother were subsequently accepted as foreign refugees on May 25, 1940. Modeste was assigned number 167801.

They met Michel Nève de Mévergnies who, like themselves, was stripped of everything except for a few small personal items. On May 28, the day the Belgian Army surrendered, they were lodged in Chiswick, by the Henry family, a quiet couple that relieved them of their misfortune. They had to adapt to the lifestyle of their British hosts, and with time, they began to appreciate the qualities and merits of their hosts. In September, the two brothers made contact with the Belgian Embassy where confusion caused a lot of tension. The arrival of the Jesuit Priest Robert Jourdain was a real blessing: while nobody was concerned about the plight of youth, the priest became a celebrity. Jourdain founded the Belgian College in Buxton, which was inaugurated in December by Prime Minister Pierlot. Hundreds of young Belgians continued their studies there, if not completing their secondary education. The Father was an ardent patriot since his youth, having also been the founder of the Free Belgium resistance during World War I.

The advice given by Father Robert helped the men understand the immediate priorities such that de Mévergnies and Modeste voluntarily enlisted in the British Royal Air Force. However, they didn’t have any aviation experience so they joined the Belgian ground forces in Tenby. Thus began a five year military career for Modeste, while de Mévergnies had his wish fulfilled: he joined the RAF as a pilot, but on May 9, 1943, died at the controls of his fighter plane which crashed near Weldon Bridge in the Northumberland. He was 19 years and 10 months old.

At Tenby, the Belgians numbered only a few hundred at the beginning of May, 1940, but, four years later, they formed a formidable unit. After having endured four difficult years of training as a commando, Modeste became a Lieutenant of an assault squad in August 1944 at Arromanches.

Note: Mr. Modeste Van Den Bogaert gave Chris Bauweraerts of Lachouffe Brewery this story in 2007. Modeste was the owner of De Koninck Brewery and passed away on October 1, 2010. In August, 2010, Modeste had sold De Koninck to Duvel-Moortgat. While Modeste was signing the sales agreement with Michel Moortgat, the CEO of Duvel-Moortgat , he stated that he was confidently placing his brewery in "good hands", with DUVEL-MOORTGAT. To commemorate the memory of Modeste van den Bogaert, the Antwerp Beer College (ABC), in collaboration with brewery De Koninck will organize the first Modeste Bier Festival on 1st and 2nd of October, 2011. Also a commemorative beer will be brewed. The "CUVEE MODESTE", a strong Scotch-style beer - a style that Modeste enjoyed particularly. This one-batch-in-a-year beer will be brewed a few days before the Modeste Bier Festival and will be cellared for 6 months before it will be released for sale.

footnotes:

(1) Jean-Baptist Piron (1896-1974), native of Couvin, took part in the First World War in an infantry regiment, then the Grenadiers. In 1942, he left Belgium to regroup in England. He becomes Lieutenant-General in 1947 and Chief of Staff – Land Force in 1951. BackDefinitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- collaboration

- Cooperation of the people with the occupying forces, more generally spoken the term for individuals who cooperate with the occupying force is collaborator.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

Modeste van den Bogaert Source: www.Go2War2.nl.

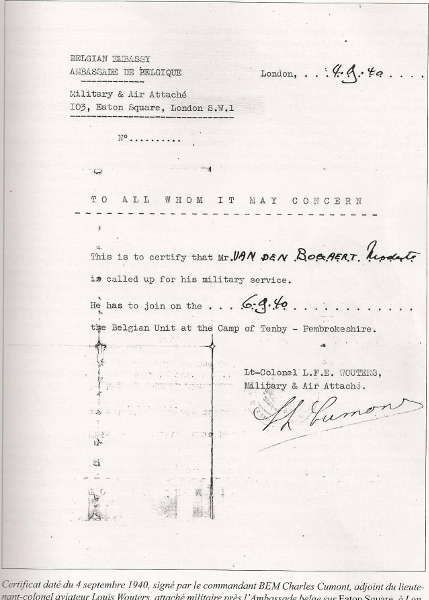

Modeste van den Bogaert Source: www.Go2War2.nl. Document in the name of the author, specifying the name of the boat which transported him to Great Britain and the number of his landing card.

Document in the name of the author, specifying the name of the boat which transported him to Great Britain and the number of his landing card.  Document dated May 25, 1940 in Southhampton, England, attesting temporary foreign refugee status to Modeste van den Bogaert, presuming Belgian nationality.

Document dated May 25, 1940 in Southhampton, England, attesting temporary foreign refugee status to Modeste van den Bogaert, presuming Belgian nationality. The Document

In old age, holes start to appear in one’s memory. Happily, not yet the lacerations which totally confuse the perception of experienced events. On the other hand, I’m not an historian, rather I am entrusting you with my personal memories.

One question is often asked: "How many soldiers landed on the coast?" We numbered 2,200 men.

Other questions:" Who were you?" Belgians, of course, but also Luxembourgers (371), Belgians from urban areas, but also the diasporas who never stepped foot in Belgium, the screw-ups, the escaped, the elders of the Foreign Legion, Belgians fighting for French, North African and Libyan armies, also deserters of the German Army, who were also Luxembourgers. (2)

"How and why did you rejoin this Belgian unit? Who took the initiative? How was it formed and how was it developed? For what mission was it conceived? By whom were they trained, equipped and specialized?" (3)

Answering these questions will cause me to reveal to you the sometimes curious or surprising sides of the brief history of the Belgians from England, or lay out the range of our differences, of our national differences, the hesitations of each, of the determination of others. There were the ambitious and the hesitant. There were the "chameleons". I give thanks for this long "Echternach walk" that continued for four years, but which, by the will and enthusiasm of some, and on the feet of this elite unit that was able to align alongside allies and bring an end to Nazism, enabling Belgium to be present in all the cenacles that have determined the fate and the future of people of liberated Europe.

1944-2004: 60 YEARS

Memories of events collide in my memory, as I try to put things in chronological order. Departing from England, the Brigade was in fact the 1st Belgian Group, which was not at all a traditional brigade, but composed of specific units whose mission was to pursue the enemy. A command staff was established and Major Piron set about organizing the battalion. Under a single command staff he grouped the various components of the organization. He eliminated individuals not fit for physical or moral reasons. He constituted a unit important enough for it to have true autonomy in combat, including the means of transportation and the ability to increase its firepower. It consisted of:

- 1. A Full Company (Headquarters Coy).

- 2. The First Belgian Fusiliers Battalion, comprising (3) companies of independent motorized fusiliers, with each company comprising three platoons of 40 assault troops ( 3 x 3 x 40 = 360 men).

- 3. A company of engineers.

- 4. 220 men armored car squadron.

- 5. Artillery battery.

- 6. Scouts (RECCE).

- 7. A unit of 3-inch mortars.

- 8. A detachment of anti-tank guns (ATK).

- 9. A detachment of anti-aircraft guns (AA).

- 10. Communications (TTR).

- 11. Medical staff.

- 12. Chaplaincy

- 13. A military prosecutor.

- 14. A liaison service.

Tilbury, England: Embarkation on the evening of August 4, 1944 in the evening on four Liberty ships - 500 vehicles and 1640 men.

Arromanches – Courseulles, France: August 5 - disembarkation.

Dover-la-Delivrande - Plumetot: August 6-10 - regroup.

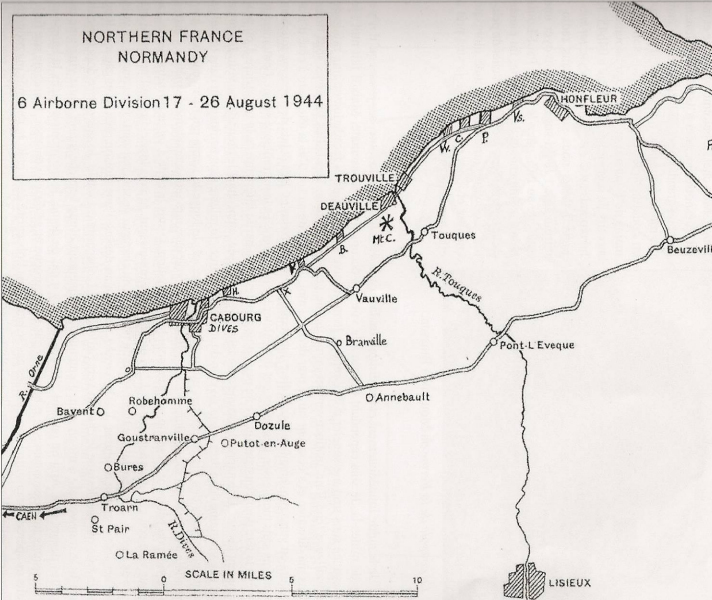

Sallenelles - Bay of Sallenelles: August 11- deployment on the front, support the units of the 6th Airborne Division under the command of General Richard Gale, including the 6th Air-Landing Brigade – a component of the Canadian 1st Army under the command of General Crerar. (4)

Footnotes:

(2) The unit was made up of servicemen who participated in "Campaign of 18 Days", among them wounded veterans evacuated to Great Britain with suffering English comrades. Modeste explains: "After being nursed back to health, they rejoined the core of war volunteers that arrived in England as civilians. A premier contingent of legionnaires of Belgian origin in the service of France then came to enlarge the ranks. They came back from Narvik where, under the orders of Koenig, they had been fighting against the Germans. Soon after, the evacuees arrived from Belgium and the occupied territories. Many of those who joined the battalion later had spent many long months in Spanish prisons. In November 1940, the Belgian government in exile in London began to call up men of military age. Those responding came from all corners of the world and many among them were forced to serve in the Belgian army, so they weren’t the most enthusiastic. Many had never set foot in Belgium or had moved away many years ago. They weren’t even familiar with the local languages. They reunited there, men from every social condition, coming from different lands, more or less of young age, more or less legitimate, those who couldn’t wait to fight the enemy and those who were less enthusiastic. After the Allied landings in North Africa, many young legionnaires, liberated from their obligations to the French government, joined the battalion. Having left Belgium in order to be free, they were arrested by the Pétain police who gave them a choice: being taken to Germany, get sent to a work camp or sign on for 5 years with the Foreign Legion in Africa. Back(3) At the beginning of his service, a soldier was paid a shilling per week. Equipment was insufficient. The most resourceful made deals with the local population. Sometimes, either for distraction or consolation, some drank. Little by little, things fell into place under the authority of officers who too their responsibilities seriously, and were well-suited for their positions. Thanks to their tireless work the battalion earned the respect of their English counterparts. They had a sense of a unified mission to defend the coasts threatened by a German invasion. Until the end of 1942 the ground forces were stationed in Wales and its bordering counties. In June, 1942, to satisfy those who were impatient, the government created a unit of commandos (Captain George Danloy) and a unit of paratroopers (Lieutenant Edward "Eddy" Blondeel). As such, the battalion ranks lost many good men to these other groups. In September 1942, the battalion was attached to the 49th Division of Royal Scotch Fusiliers. Important maneuvers took palce in South Wales. Major Piron is designated the Commander of the 1st Battallion. Manpower was readied. The unit becames a Brigade. Piron surrounded himself with devoted and qualified officers, and is promoted with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. In January '44, the Brigade is in the area of Ramsgate. In clear weather, the men could actually see the the French coast. They took part in loading and unloading exercises. Seeing the concentrations of materiel in the ports of the south, they had a preview of the big day approaching. In April however, they were sent to Norfolk. Disappointment was obvious - it was a shock for them to learn that they wouldn’t be landing on the first day of the invasion, that their turn would have to come later to put to use their prior years’ experience and training. After several weeks, the Brigade was sent to Newmarket, to receive new equipment and more powerful vehicles. After new maneuvers were overseen by high-ranking British officers, the order was given to rejoin the 21st Army Group on Normandy front. Back

(4) The 21st British Army Group comprised the 2nd British Army (Dempsey), and the Canadian 1st Army (Crerar) - which was comprised of the 2nd Canadian Corps (Simonds) and the British 1st Army (Crocker) (comprised of the Belgian Brigade, the Dutch Brigade, the first Special Service Brigade, the 6th Airborne (Gale), the 4th Special Service Brigade, the 49th West Riding Infantry Division, the 51st Scottish Infantry Division and the 7th Armored Division. Richard N. Gale (1896-1982) was made head of the 1st Parachute Brigade in September 1941; in April, 1943, he took command of the 6th Airborne Division. In September, 1944, he left the Division for the 1st British Airborne Corps. Henry Duncan Crerar (1988-1965) became head of the 1st Canadian Army in March, 1944 and held the command until July, 1945. Back

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- D-Day

- The day of the long awaited invasion of western Europe in Normandy, France, 6 June 1944. After a long campaign of deception the allies attacked the coast of Normandy on five beaches to begin their march on Nazi Germany. Often explained as Decision Day, though this is entirely correct. The D stands for Day as generally used in military language. In this case it means an operation beginning on day D at hour H. Hence “Jour J“ in French.

- Foreign Legion

- French army unit whose soldiers and officers were foreign mercenaries. Also in Spain a foreign legion is part of the military forces.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- moral

- The will of the troops/civilians to keep fighting.

- Nazism

- Abbreviation of national socialism.

- paratroopers

- Airborne Division. Military specialized in parachute landings.

- squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Images

Lieutenant Colonel Piron commanded the Belgian Brigade which liberated The coastal sector of the Sallenelles at Cabourg

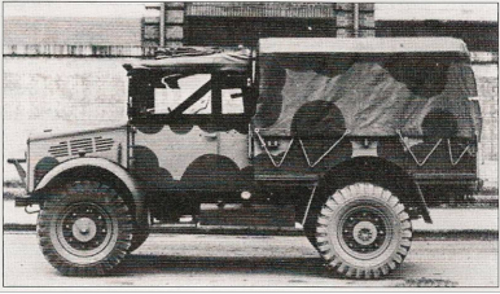

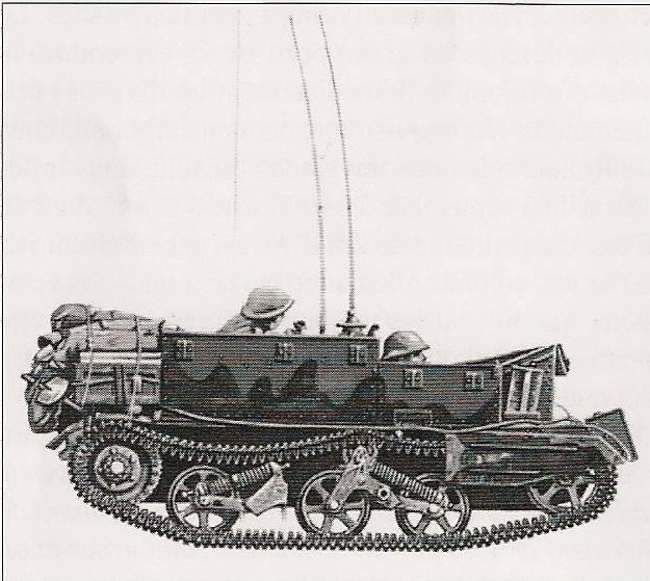

Lieutenant Colonel Piron commanded the Belgian Brigade which liberated The coastal sector of the Sallenelles at Cabourg  The Bren Carrier was armed with a Bren machine gun and was utilized for observation activities and transportation of the wounded

The Bren Carrier was armed with a Bren machine gun and was utilized for observation activities and transportation of the wounded  A Staghound armoured car in the markings of the 1st Belgian Armoured Car Squadron of the Brigade Piron.Shown on the Airfield of Ursel (B) in 2008 Source: Paul Hermans.

A Staghound armoured car in the markings of the 1st Belgian Armoured Car Squadron of the Brigade Piron.Shown on the Airfield of Ursel (B) in 2008 Source: Paul Hermans.Theatre of Operations

1. Normandy

The Sallenelles - the Orne estuary - Pegasus Bridge - London Bridge – Sites of the parachute landing of the 6th Airborne Division, where several hundred gliders littered the field, some broken, many in a better state, near bridges of the Orne Canal. The place is "Dantesque". For two months, furious fighting there had taken place without any of the combatants having conquered the other’s territory. So, each camp had all the time to fortify its positions.

The 3rd Company of the Belgian Brigade occupied the left side of the position. My platoon was located the furthest left along the Normandy front. On our left, the Bay of Sallenelles, the Orne estuary, was a muddy swamp, and the area closest to the sea submerged at each tide. A band of dunes rose up along the horizon. 850 meters in front of our positions, was an elevated mound on top of which stood a solid concrete blockhouse that was part of the defenses of the Atlantic Wall. This fortification housed a 88 mm gun, two rapid fire guns (Boffors brand), large-caliber guns (Spandau) and a battery of Nebelwerfer, also called Sobbing Sisters. Also, there were Flak guns and anti-tank weapons, the formidable Panzerfaust.

To the right of the dunes, winds the coastal road of Sallenelles-Cabourg. Even further to the right was the farm of Moulin du Buisson which held a shelter of interior fortifications that hid a defensive position that was as powerful as the one obscured by the dunes. Into the road was dug a deep crater, which served as an anti-tank ditch. This area was protected by 4 to 5 rolls of barbed wire and anti-tank and anti-personnel mine fields and many booby-traps.

The infamous Norman hedgerows bordered the meadows, where, about 1500 meters from our position, was located the formidable Merville Battery fortification of the Atlantic Wall. Their 100mm guns, protected in casemates, were aimed at the Sword Beach landings. (5) On the eve of the landings, (75) British paratroopers were either killed or wounded in attacking this battery. Of the (220) German defenders, only (20) survived unscathed. The commandos stayed only long enough to neutralize the four guns. A German counterattack was immediate and they recaptured the battery. The Germans still maintained control of the battery when we arrived.

The German soldier was, in general, disciplined, crafty, courageous and clever. However, we had a common enemy: mosquitoes – not in the millions, but the billions. At dusk, our heads were swarmed by the cursed insects. Fortunately, we were able to fashion netting around our faces with material that was originally made for colonial troops which we were able to utilize instead. Another type of wound would test us: the stinking odor of the decomposing corpses of men and of cattle in decomposition which laid everywhere on the ground. These corpses often had booby traps attached to them, so nobody ventured to move or bury them. When the air was very still, the odor was really nauseating.

The graves of hastily buried soldiers lined the paths we traveled. Rain washed away the thin layer of earth that covered them. Exposed skulls, knees, and boney toes reminded us of the tragic reality and continual dangers which we faced. Another "scarecrow" was the presence of mines strewn all over the terrain. Mines of all kinds: anti-tank, anti-personnel, jumping mines and booby traps with the cleverest mechanisms. One had to be continually worried about them.

The quality of the German armaments was superior, especially the Tiger and Panzer tanks. The 88 mm gun was a wonder. It pierced any type of shielding from a good distance, and was multi-purpose: flak, anti-tank and field cannon. The Panzerfaust was liberally provided to the German infantryman and terrified Allied tank crews. The Nebelwerfer was terrifying because it decimated us into a million pieces. The Germans were experts in the use of the mortar. They attribute more than 70% of the allied infantry casualties to mortar fire during the battle of Normandy. The Germans were tricky and ingenious and knew how to position booby traps in order to surprise us.

On August 16, 1944, an order came down for the Brigade to ready an offensive against the enemy as part of Operation Paddle (6). At dusk, three platoons of shock troops were to take positions as close as possible to the enemy positions. My group, the 4th of the 3rd Company, moved along a line about 70 meters from the road Sallenelles-Franceville, the road being impassable because of mines. We had to occupy La Ferme Blanche located at the height of the curve of the road at least 200 meters from the casemate and La Ferme du Moulin du Buisson and, if possible, to overrun this position. The 5th platoon of the 2nd Company under Second Lieutenant Raymond Van Remoortel moved along a line 150 meters on our right and crossed the sunken road leading from La Ferme Blanche to La Grande-Ferme du Boisson – different from La Ferme du Moulin du Buisson. This Grande-Ferme du Boisson was an enormous complex of buildings surrounding an interior court like our Brabanconnes farms. A sunken lane connecting the two farms was bordered by enormous hedges which ran the length of the path.

A third squad from 1st Company advanced from La Ferme du Buisson and moved towards the Merville Battery and Franceville. My squad and the one on our right achieved their objective. The Van Remoortel platoons, that of the 2nd Company, in the center, crossed the sunken road and found itself in the middle of a minefield before the first mine exploded. The men made a half-turn but mines started to explode. The Germans sighted these men and sprinkled them with a rain of mortar shell and machine gun fire. Three quarters of Remoortel’s men were wounded. The wounded men trekked to our position at La Ferme Blanche. It was 2:30 AM. My squad leader called for me and told me that our position was dangerous. If the top advisors weren’t informed that we now occupied this position, they could conclude that it was still held by the Germans and they would shell our position with our own artillery at 4:45 AM. I told him, "It’s simple, send them a message." But we didn’t have a radio, and we couldn’t locate one! I suggested sending a messenger to the Command Post, to Major Paul-Louis Nowé, Commander of the 3rd Company, a relative of our friend Pierre Nowé. My squad leader, Edouard Gonthier asked who to send and I answered him that I was ready to carry out this mission.

I left immediately and headed towards the front of the farm, on a side road, because I knew that there were no mines there. However, I was exposed to the sight of the occupants of the casemate. But it was night, and I wasn’t concerned about being spotted. I was in front of the house when a burst of machine gun fire lit up the darkness. Instinctively, I turned towards the casemate. Tracer bullets were fired in my direction and hit the wall behind me. I threw myself on the ground. My head was next to a glass transformer with electrical wires coming out of it and which were lying next to me. I was lying in broken shards of glass without getting cut. Machine gun fire broke the transformers, and then went quiet. Slowly, I raised my head to determine from which direction the bullets were coming. A layer of morning fog settled there, preventing the gunner from seeing me. I crawled about 20 meters to a corner wall of the farm. I readjusted my equipment in which electric wires were tangled up and which dragged on the ground. I walked along the edge of the farm to arrive at the hedgerow parallel to the Sallenelles road. After having walked about 40 meters, I arrived at the back of the building. Suddenly, without any warning, I am the target of machine gun fire; the gunner empties his clip with less than 12 meters of distance between me and him. Impotent, I see the flashes of arms fire which hit me in the face. The fire goes silent. The gunner’s assistant loads a new clip. I recognize his voice and overpower it with a flood of insults. I have luck on my side. I jump over a wall partition that leads to a hedgerow which borders the path towards Sallenelles. I’m in total darkness. I know that I must cross a transverse hedgerow halfway. I hear the snap of a dead branch about 20 meters in front of me. Friend or enemy? Enemy, there’s no doubt. I hurry along the large hedgerows. The footsteps are coming towards me. The man passes very close without noticing me and then his footsteps are lost in the darkness of the night. I resume my journey towards Sallenelles. A sentinel orders me to stop. Password? I did not forget it. The sentinel approaches me in astonishment. Justifiably so, as he has just spotted a German patrol and I came out of the same spot where the enemy had disappeared into the night.

Without delay, I went to the Command Post of Major Nowé. When he saw me, he asked, "How many dead? How many wounded?" I could reassure him; when I left the platoon, there were no casualties. On the other hand, 2nd Company had about 10 wounded at La Ferme Blanche. From his observation post at this distance, it was obvious that he could have mistaken us for the enemy. He offered me a glass of wine, and then another which I had no difficulty in drinking. He now knew that La Ferme Blanche was in our hands. I left with five medics back for my post at which the wounded continued to arrive.

Once back, I learned of the death of Raymond Van Remoortel, my friend, aspiring Commander of 2nd Company. He had been wounded by an explosion of mines. Having refused any assistance, he dragged himself to our position. He was probably wounded a second time. An enemy bullet completed its mission and his body was retrieved by Leon Zielinsky.

Dawn breaks. We are regularly hit with heavy enemy fire from atop a hill, safely in his fortress, the enemy dominates our position. Our artillery and 3 inch mortars punish them accordingly. The day progresses and we remain pinned down. The slightest movement results in a barrage of gunfire or mortar rounds. Nothing to drink, no food, just the exchange of gunfire between the two camps. During this time, our armored tanks engaged fire at the crossroads near La Ferme du Buisson. They progressed in small steps along the gigantic hedges, parallel with the German positions, because this route is truffle of mines. These smart fellows laboriously draw out enemy fire.

Around 16h00, hidden by the high vegetation, the armor-plated car of lieutenant Henri Sauvage (Troop I) arrived without difficulty to La Ferme Blanche, to the crossroads about 150 meters from the bunker. The 88 cannons fired two shots. Fortunately, its trajectory sight was put out of order earlier when hit by one of our mortar rounds, so the 88 shells missed their targets. It was the last time that this gun spit. Our artillery and the cannon from Sauvage’s armored car took it out. The enemy’s resistance was bending.

During this time, a platoon from 1st Company, left La Ferme du Buisson and cut a passage through the mine fields and infiltrated the enemy positions by working around its defenses. A squadron of the 12th Devonshire and elements of the First Royal Ulster Rifles infiltrated and overran the Merville Battery positions. (7) The defenders easily gave up this strong point of the Atlantic Wall. Franceville was captured by the men of the 1st Company; enemy positions were captured one after the other.

We explored the entrances to La Ferme Blanche and discovered, on the other side of the road, in front of the farm, approximately 20 dead cows in an advanced state of decomposition. Around the abandoned, elevated German positions were ten disseminated corpses. Another twenty wounded soldiers were laying about the immediate surroundings and about forty who weren’t seriously wounded were taken prisoner, while a few others escaped. The bottleneck which for two months prevented any advancement along the coastal route was finally overcome.

Miraculously, we deployed our platoon and suffered only light casualties. Without hesitation, we pursued the fleeing enemy. We went past Franceville. It’s approximately 20h00 when we arrive at Hôme-sur-Mer. The first supplies for this day reached us here. We bivouacked in the village school, but we all couldn’t stay there because mortar shells were striking all around us. It rained abundantly. I was exhausted and fell asleep on a pile of gravel. During the night, I laid underneath my trench coat, which slipped off without my realization and I slept for several hours without being covered. As a result, my clothes were thoroughly soaked.

August 18 – my birthday, but I don’t even think about it. Two days pass. We clear the field of mines. We hauled in a righteous booty. We also cleaned and serviced our equipment. On August 20th, we arrived in Cabourg and passed through la Dives. All the bridges were blown up, so our wheel vehicles with our supplies couldn’t cross. So, we lugged our weapons, ammunition and a few small bags. The Belgians then took the city of la Dives, then Houlgate. Next, we climbed la bute de Chaumont where we waited for the enemy. We lost five men including an FFI officer.

From ambush to ambush, we progressed along the coastal road. We successively liberated Auberville (Intersection Marie-Antionette. In fact, the main road through Auberville is now called Rue Brigade Piron 21-22 Aout 1944.) Villers-on-Sea, Blonville-sur-Mer (Mont Canisy Battery) and reached Deauville. Enemy resistance stiffened at la Touques, Trouville-sur-Mer, Pont-l’Évéque and Lisieux. The battalion of fusiliers continued its progression along this route and took Villerville, Cricqueboeuf, Pennedepie, the coast of Grâce et Vasouy to emerge at Honfleur, where I lead the advance. We passed the Church of Saint-Catherine and descended towards the basins; we went along their entire length - a walk frequented by today’s tourists. We headed immediately towards the mouth of the Seine. The local resistance had already made our task much easier.

Let’s return to the armored tanks. Since the beginning of Operation Paddle, our armored tanks supported the 6th Airborne Division which progressed on the axis of Caen, Troarn, Dozule, and Pont-l’Évéque. They were the backbone of this unit. It was at Branville where Lieutenant Roger Dewandre (later Lieutenant-General), distinguished himself in traversing severe enemy fire in crossing the town, then still occupied by hundreds of Germans, in order to inform the command of the 6th Airborne of the enemy positions. His actions earned him the Military Cross. Risle, small tributary on the left bank of the Seine, was the next obstacle. We moved on to Foulbec, which was 7 km to the south of the modern bridge at Tancarville. The Germans observed us from a wooded peak where they were positioned with four 88’s and a dozen large gauge mortars. They let us stumble into their trap. It was at this time that our armored tanks joined us. The platoon led by Léo Van Cauvvélaert arrived at the crossroads near the Risle bridge which had been blown up. My platoon followed at 150 meters. It was at this moment that a fiery hell rained down on our men. We were blinded and asphyxiated by the acrid smoke from the explosions. Several comrades were killed. The divisional artillery executed a fire bombing on the German position in the woods. Several airplanes also took part. Having taken care of them, we advanced towards the east, towards the forest of Brotonne, in a buckle of the Seine. Forty thousand Germans were taken prisoner. Thousands of horses and mules wandered in the forest. Hundreds of corpses were lying under the trees of the forest. It was stunning.

Footnotes:

(5) The German command of the Merville Battery was Lieutenant Steiner. The battery held four main bunkers protected by machine gun nests and 15-20 cannons. The site was neutralized by the 9th British Paratrooper battalion, lead by Lieutenant-Colonel Terence Otway, just before the first landings on Sword Beach. Back(6) Operation Paddle – the code refers to the many rivers, marshes and flooded zones which barred the roads out of Normandy towards the Seine. This offensive was launched the moment they completely encircled the German forces in the Falaise-Argentan pocket.Back

(7) The 12th Battalion Devonshire Regiment and the First Battalion Royal Ulster Rifles belong to the 6th Air-landing Brigade of the 6th Airborne Division. The Devons arrived by sea, the Ulsters were transported by air in the Ranville area. British airborne divisions were linked up (two parachutists and an airplane) comprised of battalions, elements of various weapons (artillery, anti-tank devices and anti-aircraft) and support services (also paratroopers and airlifts). The regiments were administrative units and sub-divided by battalions, of which the number is function of importance of the recruitment in the area of origin of the regiment. In the case of the 12th Devons, the recruits told stories of Devonshire.Back

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- caliber

- The inner diameter of the barrel of a gun, measured at the muzzle. The length of the barrel is often indicated by the number of calibers. This means the barrel of the 15/24 cannon is 24 by 15 cm long.

- cannon

- Also known as gun. Often used to indicate different types of artillery.

- casemate

- Enclosed bombproof area, made out of stone or concrete and used to install guns and/or other firearms. Casemates contain various loopholes to enable gunners to use their weapons. They are part of a larger defense system (roundel, bastion, fortress and others) or are an indiidual defensive position in a defense line. In the Netherlands the word (as kazemat) was standard use for a bunker or pillbox.

- Flak

- Flieger-/Flugabwehrkanone. German anti-aircraft guns.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- machine gun

- Machine gun, an automatic heavy quick firearm.

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

- mortar

- Canon that is able to fire its grenades, in a very curved trajectory at short range.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- Panzerfaust

- German anti-tank gun used by the infantry. Consists of a long tube with the grenade mounted at the front side. It was a disposable weapon. After being used it cannot be reloaded. Major disadvantage is the long flame back blast from the tube.

- paratroopers

- Airborne Division. Military specialized in parachute landings.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Images

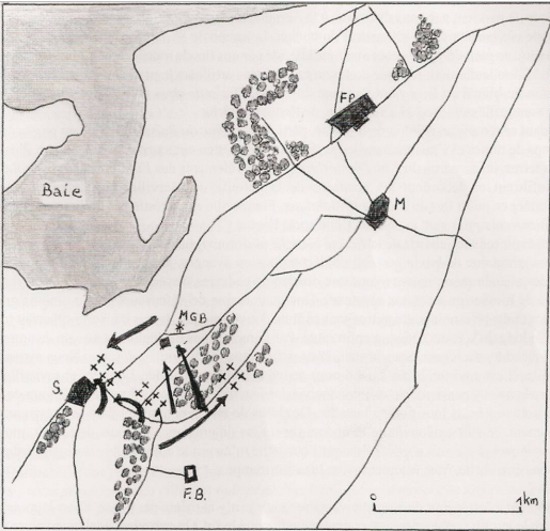

Attack on "Moulin du Buisson". S=Sallenelle - FP=Franceville-plage - M=Merville - MGB= "Le Moulin du Grand Buisson" - F.B.="Ferme du Buisson".

Attack on "Moulin du Buisson". S=Sallenelle - FP=Franceville-plage - M=Merville - MGB= "Le Moulin du Grand Buisson" - F.B.="Ferme du Buisson".  D Day Merville In Normandy Remembers Fallen Source: YouTube.

D Day Merville In Normandy Remembers Fallen Source: YouTube.The next Theatre of Operations

2. Right Bank of The Seine

On August 30, we crossed the Seine above Caudebec-en-Caux. We walked west towards Le Havre, the large port city. Bolbec and Harfleur were occupied by armored tanks. The battalion of fusiliers was deployed, ready to defend the big harbor. However, on September 1, the Brigade received orders to fall back. We had to promptly rejoin the Britannic Division and move north. After regrouping and refueling, we moved quickly east towards Rouen, which we crossed. Next, we changed directions to the north and reached Arras September 3 at 04h00. On the nights of the 2nd and 3rd, at about 01h30, a rather unusual event took place: about 50 km from Arras, in the darkness, a Brigade column was inadvertently joined by a German vehicle column. The presence of two Tiger tanks filled those who witnessed it with terror. Fortunately, the German column left as discretely as they appeared. When one considers the carnage that these tanks would have wrought on the Belgian column, it’s remarkable that we escaped so easily.

At Arras, the Brigade was put under control of the 30th Britannic Corps, led by General Horrocks. He contacted Piron and shared his plans with him: "Tomorrow, I plan on taking Brussels; your presence on my flank is indispensible. Your motorized column will escort the tanks of my Welsh Guards (8) to intervene in case they are stopped by obstacles or your infantry can provide assistance." And so began the triumphant march towards Brussels. (9)

3. Belgium

On September 3, we crossed the French-Belgian border at Rongy, to the south of Tournai. (10) It is a moment of great emotion. We crossed Peronnes, Antoing, Leuze, Ath, Enghien; we were stopped at Bierghes. We hit a patch of resistance at a park in Enghien and it was necessary to put it down, but local partisan resistance took care of it for us. During this time, Captain Rene Didisheim accompanied the forward observers of the Welsh Guards which emerged on the main square of Brussels; Burgermeister Jef Van de Meulebroeck just established his office at city hall. (11) On September 4, the Brigade, escorting the Welsh Guards, entered the capital by the Porte de Halle. It was delirium. My unit had to return to the Grenadiers’ barracks to get quartered for the evening. The next day, my company took a position at Zaventem and Evere where pockets of resistance still existed. (12) We stayed there two days after which we stayed in the barracks at Vilvorde. We enjoyed two days of rest, but were busy washing clothes and cleaning our equipment. Some among us had the authorization to rejoin their family. The country was still not yet completely liberated.

On September 11, the Brigade left the Brussels’ area and crossed Louvain, Diest, Schaffen and Paal and established a bridgehead at Beringen. While crossing the Canal Albert, mortar shells exploded all around us. We headed in the direction of Beverlo. We take the direction of Beverlo and to a place in front of the church at Heppen, to the west of Bourg-Leopold. The area was wooded and the enemy was everywhere. We identified a German detachment of motorized cannons at Oostham. (13) My platoon occupied the northwestern edge of the village. Around 17h00, with the assistance of three men, I took on the responsibility of finding food for the evening. In crossing the main square of the village, we noticed a British tank and several vehicles of the 3rd Company, Bren Carriers, several 15 cwt Bedford, etc. People were gathering everywhere. We passed in front of the church and crossed the road leading towards Bourg-Leopold. We gathered on the median surrounded by village school buildings. The cooks had set up their ovens and the evening supper was served. Suddenly, we heard the sound of an explosion. We went back and saw an enormous, gray cloud of dust enveloping a tank. We thought the tank started a fire, which always created a similar cloud of dust when the ground was dry. We realized we were wrong when we heard the shrill whistle of about twenty falling projectiles. We scrambled for shelter. I hit the ground with my head behind one of the front wheels of a 15 cwt Bedford. Shells were bursting everywhere then followed by silence. I heard persistent breathing. I lifted my head; a metal fragment about 60 cm long had grazed my helmet and cut a horizontal tear in the tire which was deflating slowly. Immediately, I realized I might have been wounded and discovered a cut on the index finger of my right hand. Once again, I had been frightened, but came away without serious damage.

At the church square, it wasn’t going as well. The devastation was extreme. My friend Charles Van Oppens, of the Van Cauwelaert platoon, had his skull fractured by an explosion. Other men are less seriously wounded. The Bren Carriers were destroyed. And the enemy was always observing us. At Hechtel, the British advance guard, which overflowed camp Borough-Léopold, clashed with the SS. Street battles took place at Hechtel for two days and the Germans managed to retake the village twice. The village was completely destroyed. Not a single house remained intact. Meanwhile, our 2nd Company surrounded camp Borough-Léopold. We accomplished an unforeseen task there, the release of 950 political prisoners that had been imprisoned by the Dutch SS – the same ones that clashed with the British at the Hechtel intersection.

On September 12, the enemy still occupied the woods in the area and badgered us relentlessly. The snipers were a major problem. That same day, my platoon was in Heppen. In the afternoon, we received an order to conduct a patrol to flush out these marksmen hidden in the surrounding woods, in the direction of Oostham. I offered to lead the mission. As we were leaving our position, Louis Goetz, officer-candidate, recently attached as head of our group, seeing me take the lead, instructed me to yield the command to him. So he took my place. The patrol flushed out the enemy and they could easily identify Goetz as the commander because of his ostensible officer stripes of which he was so proud. The bullet intended for him rebounded off of his revolver, given to him by his father, and struck him in the chest. Corporal Andre Devos ran to his side and Goetz had enough strength to say "I’ve been hit in the heart," before he succumbed. Louis was a charming, worthy comrade whose reasoning was persuasive and who is dearly missed. I question myself still, why him and not me?

On September 13, beyond Heppen, our squad took a position along the Bourg-Leopold railway line, in front of the train station. At dusk, we observed a procession of walking ghosts – recently liberated political prisoners, dazed and wearing only tattered rags. It was shocking! The next day, my squad occupied the edge of Bourg-Leopold along the road leading to Lommel. Our view was blocked by tall trees occupied by the enemy who could observe us. In the afternoon, a sniper’s bullet fired from a long distance – we couldn’t even hear the rifle shot – grazed the top of my helmet after which it lodged in the ceiling of the shed we occupied.

On September 15 and 16, we stayed in Bourg-Leopold. On the 17th, a Sunday, we were the amazed spectators of an aerial parade of hundreds of gliders flying right above our heads. It was the beginning of "Operation Market Garden" which had as its goal the capture of the bridges at Eindhoven, Nijmegen and Arnhem, and the opening of a passage in the Ruhr basin. The same day, the 30th Corps of General Horrocks went on the offensive to rejoin the airborne troops dropped in the areas of Nijmegen and Arnhem. The tanks of the Welsh Guards, supported by the 50th and 45th Divisions, drove a line from Hechtel towards Neerpelt, Lommel Valkenswald and Eindhoven. The weather was overcast so the fighter bombers could not intervene. The Germans were entrenched in the woods on either side of the route. The British had the task of extracting themselves from this situation. After heavy losses, however, they were successful in breaking the headlock. Valkensward and Eindhoven were taken.

On September 18th, we received orders to defend the right flank of an attack from our position in Neerpelt to Eindhoven. Our artillery covered the movement of Allied troops to the north at the very limit of our range of fire. The next day, the 3rd Company crossed Hechtel, in ruins, and around Wijchmaal and Peer towards Kaulille, on the south bank of the floodway. We occupied the Coopal factory and had some difficulty in suppressing enemy incursions south of the canal. Our men captured fifteen soldiers of Asian origin from the Vlassof army. At Bocholt, the Germans launched their soldiers on the south side of the river and the Maton squad of 1st Company was harassed by snipers that our 6-pounders took out. In general, the enemy remained vigilant and continually harassed us. We captured three German parachute platoons.

September 21 - My squad received orders to take a position on the south side of the canal between Kaulille and Bocholt. We were marching single file behind the Van Caulwelaert platoon when suddenly a detonation occurred. Then Frans Rombauts, wounded in the head, was felled by a sniper’s bullet. On the 22nd, a tank column crossed the canal. It seemed the enemy retreated back to Weert. Then the Weert area was liberated and our engineer, Lieutenant Lefevre, was instructed to span a Bailey Bridge across the canal on the Bree-Kessenich route (towards Roermond, NL).

On September 25, the Brussels Bridge was inaugurated by Piron at 08h15. Our armored tanks had crossed this bridge charging towards Maaseik. It is the same bridge that the whole 21st British Army used for launching its attack on Roermond and Venlo in Dutch Limbourg. Our tank group used it as well for reaching the Wessem-Weert canal when the Germans attacked during the crossing. For them, it was henceforth about defending their homeland (Heimat in German). They still held the bridgeheads on the southern bank of the channel. Upon leaving Maaseik, we followed the Meuse and we deployed south of the channel. Our infantry occupied Ophoven, Kessenich, Thorn, Ittervoort, Hunsel and Ell. It was September 25; we remained stuck there for 50 days, from September 29 until November 17. The front extended for 20 km. We occupied in fact a chain of strong points, often separated by more than one kilometer, from one to the other. If we had to defend our position during the day, the American tanks would have come to assist us. At night, it was a completely different scenario because the German patrols would penetrate our lines and aggressively circulate behind our positions. The fog often worsened the situation by reducing the visibility to nothing. So, we ensured the bond joining the British army on our left and American on our right; we occupied the angle formed by the Meuse and the Wessem-Weert channel. Here are some highpoints of this period of time:

- On September 29, the Brigade was placed under the command of the 29th US Army and received the support of a number of tanks. October 2, the Brigade executed an infrastructure attack to seize Wessem, fortunately without a casualty. October 7, we received a visit from Prince Charles, regent of Belgium, and the mail problem was resolved. October 10, fourteen men, ten of which were from my platoon, disappeared in the fog of night at an advanced post of Sandfort. October 14, the infantry of the 1st Company attacked Ittervoort at night, possibly with local assistance. October 16, during an offensive at Wessem, six men from my platoon were taken prisoner and the head of the Gonthier platoon was taken out of combat. We lost two of three machine guns.

- October 18, my platoon occupied a brick factory, halfway between Thorn and Wessem; the platoon was reduced to less than two-thirds of the men. We lost two of three Brens; we did however retrieve two Spandau’s (MG42) and munitions from the enemy. We were under attack the whole evening; it was almost hand-to hand combat. At dawn, we identified four of our assailants, paratroopers from the Herman Goering division.

- October 27, a German patrol of 40 men infiltrated Thorn. Street fighting ensued. There was a lot of destruction. Result: the enemy had 4 killed, 6 wounded and 30 prisoners. On our side Chaplain Nobels took a bullet in the chest, the Nurse Sergeant Barra was found in his underwear having been taken prisoner temporarily by the Germans, and we transported five seriously wounded soldiers.

- October 31, we were placed under the command of the 8th British army. We were relieved by the 53rd Welsh Division, the 4th Armored Division and the 7th Infantry Brigade which occupied our sector. Our Brigade was placed along 2km of the front.

- From November 2 to 6, we conducted numerous patrols.

November 6, General Dempsey, commander of the British 2nd Army, arrived in person to congratulate the men of the Brigade for their accomplishments.

November 9, Lieutenant Colonel Piron was informed of a large scale attack would take place near the Brigade positions. Roermond and Venlo were the objectives. Snow started to fall but melted the next day. It was cold.

November 10, the enemy was nervous. The Brigade was given the mission of establishing a bridgehead on the north side of the Wessem-Weert canal on the evening of the following day between Hunsel and Ell. - On the morning of November 11, our platoon was subjected to a shelling from 88mm cannons. Exploding shells burst shrapnel above our heads. Two of my platoon sergeants were injured a few hours apart in the afternoon: Jean Boijen and Robert Beyen. I helped evacuate them to the aid station. When darkness fell, the Brigade artillery unleashed a violent shelling on enemy positions as Rogge of the 3rd platoon of the 2nd Company attempted to establish the bridgehead. They fired 3-inch mortars and artillery. As the boats were placed in the water to cross the canal, a smoke screen hid them from the view of the enemy. Rogge was able to set foot on the other side, but the losses were heavy: 4 killed, 9 seriously wounded and 1 slightly wounded. Rogge himself was hit by shrapnel, but was unwilling to be evacuated until he was certain the bridgehead was established. He returned to the friendly side of the river where 1st Sergeant Silverman came to welcome him. They took seats in a Jeep and drove to the aid station. It was about 21h30.

While Rogge prepared his assault, my squad was charged with protecting its flanks. With four men, I left the stand of fir trees where my platoon was in position. I crossed a plowed field approximately 250 meters across and arrived at the bank of the canal above an abandoned farm where men of our armored tanks were on the lookout. The canal is bordered by a path established on the high bank about 1.5 meters. After having crossed this obstacle, one had to take the tow path downwards. The sky was cloudy and produced total darkness. On our right, at about 600 meters, the Germans always held a bridgehead on our bank. The danger was that they sent men to attack the Rogge home base which was 400 meters to our left. In fact, my patrol is in position more or less halfway between Rogge and the enemy. Arriving at the bank, we heard German voices which reached us from the opposite bank of the canal. The Germans apparently wanted to move a piece of artillery in order to take the interconnecting bank along the waterway.

I ordered my men to remain safely on the canal bank while I moved to the sloped bank on the other side of the canal. The efforts of the enemy to move their artillery proved futile because of the extremely wet condition of the earth due to recent rains. For five minutes, I observed their movements and I heard the officers swearing at their men. A light breeze agitated the surface of the water and resulted in continuous splashing. Turning to my right, I observed in the darkness, along the surface of the water the shadows of strange shapes which weren’t there a moment before. I realized that there were shadows of an enemy patrol which was moving down the tow path.

At this time, one of our own, which occupied the farm, crashed through a roof. The noise was heard by the soldiers of the enemy patrol who immediately froze. The officer leading the patrol was very close to me. With a hand signal, and without a single word, he ordered his men to squat down. I observed their little game, and I take a Mills grenade in hand. My Schmeisser was ready to fire but I waited. The last two men in the German line fixed the tripod of their machine-gun. The head of the patrol was now squatting. Sensing my opportunity, I straddled the bank while escaping from the bullets of several automatic weapons. I retrieved my helmet, which I had lost in my haste. I launched a grenade which explodes but I am also the victim of several German grenades. My sight was completely obscured by two blasts to my left eye; my right eyelid was also wounded. I felt intense heat in my chest. I opened my uniform and felt my chest with my right hand – nothing there. I was still trying to locate the wound when blood squirted out of my neck. I realized the tragedy of my situation. I gripped the wound with my right hand and raised my eyelid with my left hand. I saw moving shadows. One of the men from the farm came to my assistance. Together, we crossed the plowed field, the 300 meters that separated us from the stand of fir trees. Blood ran abundantly. I lay on a stretcher and was transported to the rescue station. There were 400 meters to cross but a German patrol operated behind our positions. We wasted valuable time, but it all worked out. The stretcher was deposited on the hood of a Jeep that came to meet us and we drove to the aid station at Hunsel. It was also at this same time that a Jeep was transporting Gerard Rogge and Silverman to the same aid station. I heard a violent explosion; their Jeep had just driven on top of a mine. Rogge and Silverman were killed.

I was placed in a medical tent full of many wounded and dying. A doctor listened to me and observed my wounds under an electric light. He told me, "I have no blood with which to give you a transfusion because my supply is all exhausted, but tell me how you were able to stop the hemorrhaging?" I told him, "I pinched the wounds." As such, he told me to keep pinching them. I was transported by ambulance along with many other wounded. Roads were made difficult by the rains and the English supply lines slowed all movement. British divisions were preparing an attack which had to pass through the bridgehead established by Rogge and his men. Behind our lines, 400 pieces of artillery were ready to open fire on the enemy in preparation for the invasion. (14) The ambulance could finally move through the traffic after two hours of vain attempts. It was 02h00 November 12 when we arrived at Wijchmaal (Peer) where the Brigade hospital was located. Medical Capitan Vermeylen, a friend, notified of our arrival, gave me the essential blood transfusion. I had a pierced carotid artery. I recall being very cold during the transfusion and fainting at the beginning. Once the transfusion started, I lost consciousness. I was transported to the main hospital in Eindhoven where I regained consciousness. Moreover, I had to explain how I was wounded – enemy action or self-inflicted (15) – before being admitted into an operation room. With the aid of a scissors, all of my uniform, soaked with blood, was removed. A grenade rolled out of one of my pockets and onto the operating table. Panic in the room. I took it in my hand and was reassured that the pin was still in it, and handed it to an assistant. My wounds were treated and two days later, I was flown to Brussels in an old tin can – a Handley-Page from WWI! The wind gusted and it rained buckets. It was an eventful, shaky flight. The men with broken bones screamed in agony. I was transported from Brugmann to Jette.

The Ophthalmology unit was extremely busy during this period of time. The main Ophthalmologic doctor, Stallard, a track and field athlete in the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, removed the foreign object from my left eye. For a month, I could not move with a bandage wrapped around my eyes. I was then transferred to a convalescent home in Tournai. (16) A month after that, I left for Brussels, this time to a military hospital on Couronne Street. The conditions were unpleasant: I was placed in a large common room with about 40 other wounded, some Belgian, but many British and often in worse shape than me. Doctor Lister was very thorough and discovered a second foreign object in my left eye. After extraction, I stayed another month in this room. It was freezing on account the coal reserves for heat had been reduced to nothing. The authorities were stingy and the rations were scrupulously controlled. In the room, all we had was a single coal stove that we could burn for one hour in the morning and one hour in the afternoon. We had to eat our meals in the central kitchen with the help of wounded German prisoners.

Beginning on February 20, 1945, I was placed on sick leave that I spent with family in Aartselaar. So I had the opportunity to get to know the V-1 and V-2. On March 25, I returned to the military hospital on Couronne Street for an exam where I was determined to be fit for service. April 15, I became an instructor for young recruits at Bourg-Leopold. I stayed there three weeks before being transferred to the Reinforcement Holding Unit in Neerpelt, where I served until June 3 as a 1st Sergeant Major.

It was there that I saw the end of hostilities and the unconditional surrender of Germany. I left with a paid vacation for three months from the State and on September 3, I could enjoy an unlimited leave, in other words, my demobilization. Around September 15, a rural policeman from Aartselaar came to find me and to personally give me, ironically, a military order to return me to the barracks for military studies. At that time, I was studying the course material to receive a degree in Agronomy and attended class in my uniform because I had not taken the time to acquire civilian clothing. I did not take time to acquire civil clothing. Needless to say, the rural policeman was issued a categorical refusal and returned empty handed.

Footnotes:

(8) The badges boar "Welch" and the English transcription "Welsh" appeared in the publications mentioning the original units from Wales. The Guards Armored Division was composed of the 5th Guards Armored Brigade, 2nd Armored Battalion Grenadier Guards, 1st Armored Battalion Coldstream Guards, 2nd Armored Battalion Irish Guards, 1st Motor Battalion Grenadier Guards; of the 32nd Guards Brigade: 5th Battalion Coldstream Guards, 3rd Battalion Irish Guards, 1st Battalion Welsh Guards; of divisional troops: reconnaissance (Household Cavalry), anti-tanks, artillery, anti-aircraft, communications, and engineering. Command: Major General Alan H.S. Adair from October 1942. The 32nd Brigade follows the axis of Tournai, Leuze, Ath, Enghien, Hal with, on its left flank, the 5th Brigade. Little before 20h00, a tank of the 2nd Household Cavalry Regiment, in reconnaissance for the 32nd Brigade, penetrating into the capital. Back(9) The Piron Brigade included 110 officers, 1880 non-commissioned officers and troops and 500 vehicles. Back

(10) The first vehicle of the Piron Brigade crossed the border at Rongy on September 3, 1945 at 16h45. Back

(11) It was at 10h00 September 4, 1945, that Captain Didisheim made contact with the Burgermeister of the capital, re-establishing his office by the Resistance the previous evening. Back

(12) The three motorized infantry units of the Piron Brigade was stationed at Evere, at Melsbroeck-Zaventem and at Petit-Chateau, the tank squad and the artillery battery occupied the Etterbeck barracks. Back

(13) C. RYMEN, the Panzerjager-Abteilung 559 at Limbourg (September 1944), Beringen combat, Beverlo and Oostham of the 3rd Company (Lieutenant Franz Kopka) of Panzerjager (559th Battalion of Major Erich Sattler) supported by the foot soldiers of the 3rd Infantry Regiment 723 (Colonel Vehrenkampf) of the 719th Infantry Division, the paratroopers of the 1st Fallschirmjager-Regiment 2 (Captain Finzel), of the Fallschirmjager-Regiment 6(Lieutenant Colonel von der Heydte) and of the 7th Fallschirm-Division (General Erdmann), elements of the SS Battalion Landsturm der Niederlanden. These units were commanded by General Kurt Student which momentarily occupied a Command Post at Heppen. Back

(14)Modeste adds: "The allied artillery attached to the Belgian battery pounded the German positions beyond the Wessem-Weert canal. Then it was the tank flame throwers that sprayed the enemy defenses along the canal with their flaming liquid. They were followed by amphibious tanks with Flails (spinning chains with steel balls for clearing mines) which crossed the canal, in front of the British Infantry. The attack was successful without too much loss of life. Roermond fell and Venlo was taken. The Brigade retreated from the combat zone November 17. Our troops enjoyed a well-deserved rest at Louvain. As such, the Brigade ceased its activities. Special weapons such as artillery, tanks, engineering were separated. The First Belgian Fusiliers Battalion was used to frame a new unit that inherited the prestigious name of the Piron Brigade whose manpower was considerably increased. This unit was distinguished as an Allied unit from April 5 until the end of hostilities." Back

(15) Priority was given to men who were wounded in combat over those that had self-inflicted wounds. Back

(16)Modeste adds: "The convalescent center at Tournai was situated in the old barracks, and was outdated and uncomfortable. There wasn’t a single officer among the men. The center was under British command and had only non-commissioned officers and regulars. We wore special uniform, dark blue and resembling pajamas more than a uniform. Demanding forms of discipline reigned and the program included a lot of exercises. There were wood and mechanical shops. At the back of my room, along the outside wall, I could see a small, peaceful garden with trees. But in the center was a post made from a railroad tie. It was an execution post at which several partisans were shot. There were some wilted flowers at its base. I had the impression that I was in a detention camp instead of a recovery center. Back

Definitielijst

- Abteilung

- Usually part of a Regiment and consisting of several companies. The smallest unit that could operate independently and maintain itself. In theory an Abteilung comprised 500-1,000 men.

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Cavalry

- Originally the designation for mounted troops. During World War 2 the term was used for armoured units. Main tasks are reconnaissance, attack and support of infantry.

- heat

- High-explosive anti-tank warhead. Shaped charge projectile to punch through armour. Used in e.g. bazooka or in the Panzerfaust.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

- mortar

- Canon that is able to fire its grenades, in a very curved trajectory at short range.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- paratroopers

- Airborne Division. Military specialized in parachute landings.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- shelling

- Indication for shooting targets with grenades. Both from artillery and armoured artillery.

- sniper

- Military sniper who can eliminate individual targets at long distances (up to about 800 meters).

Images

Churchill tank crews of 34th Tank Brigade watch the RAF bombing the defences of Le Havre, 10 September 1944 Source: Wikimedia.

Churchill tank crews of 34th Tank Brigade watch the RAF bombing the defences of Le Havre, 10 September 1944 Source: Wikimedia. The British Army in North-west Europe 1944-45 Churchill bridgelayers, Sherman flail tanks and infantry during the assault on Le Havre, 13 September 1944 Source: Wikipedia.

The British Army in North-west Europe 1944-45 Churchill bridgelayers, Sherman flail tanks and infantry during the assault on Le Havre, 13 September 1944 Source: Wikipedia. Scenes of jubilation as British troops liberate Brussels, 4 September 1944. A carrier crewed by Free Belgian troops (Brigade Piron) is welcomed by cheering civilians Source: Wikimedia.

Scenes of jubilation as British troops liberate Brussels, 4 September 1944. A carrier crewed by Free Belgian troops (Brigade Piron) is welcomed by cheering civilians Source: Wikimedia. Crossing the Seine and the advance to the Siegfried Line 24 August - December 1944: The inhabitants of Brussels greet British and Belgian troops after the liberation of the city Source: Wikimedia.

Crossing the Seine and the advance to the Siegfried Line 24 August - December 1944: The inhabitants of Brussels greet British and Belgian troops after the liberation of the city Source: Wikimedia. Joseph Van de Meulebroeck presents colours to the British Guards Armoured Division at the victory parade in Brussels in 1945 Source: Wikipedia.

Joseph Van de Meulebroeck presents colours to the British Guards Armoured Division at the victory parade in Brussels in 1945 Source: Wikipedia.Afterword

What did I retain from this turbulent period of my life?

- The friendship of today which unites the survivors of this epic period and the intimate, fraternal ties that connect us from the danger that we faced together, arm in arm.

- The satisfaction of seeing that our efforts and pain were not in vain and that for 60 years, Europe hasn’t had an armed conflict.

- The discovery that, when the situation was truly perilous, when the future of the country was in jeopardy, the Flemish, Wallons and the people of Brussels could form a single, welded and interdependent body.

- The pride that comes with the fact that the Belgian Brigade could respond to a higher calling with courage, which was proven by the vast majority of the men that served.

- The chance to walk shoulder-to-shoulder with men of exceptional valor, which was a source of moral support, and proved the real value of human life.

- The realization, during our stay in Great Britain, the qualities of a people standing up to the challenge launched by the Nazis against the entire world, when everywhere else, the vanquished had lost hope.

Disappointments, however: Many of our contemporaries are unaware or pretend to be unaware of the consented sacrifices made during this trying time by our countrymen who remained in the country under the boot of the occupier and by those who took up arms to fight. Let us not forget that ignorance and insouciance are the germs of intolerance. Lastly, I think that our modern society has to remember those who possessed the best qualities human beings have to offer, sacrificing their lives so that others could live in freedom for generations to come.

I would like to recognize the thousands of aviators who faced the most perilous of situations, to those who fought the battle of England, to the aerial combatants, to brave soldiers on all sides, to the sailors of the allied fleets, to those of British Navy, Belgian Navy, to all of the allied navies, without forgetting those of the merchant marine, which battled the enemy underneath - the submarines of the Kriegsmarine.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- moral

- The will of the troops/civilians to keep fighting.

Images

The gravestone of Modeste van den Bogaert on cemetery Schoonselhof. He has been burried as a resistance fighter and veteran Source: Grafzerkje.be.

The gravestone of Modeste van den Bogaert on cemetery Schoonselhof. He has been burried as a resistance fighter and veteran Source: Grafzerkje.be.Information

- Published by:

- Leo G. Lensen

- Published on:

- 13-02-2016

- Last edit on:

- 21-11-2023

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related books

Sources

- FLORENTIN, EDDY, Operation Paddle, Presse de la Cite, 1993.

- OTWAY, TERENCE B.H. LT-COL., D.S.O., Airborne Forces, Imperial War Museum (May 1990), London, 1990.

- WISE, TERENCE, D-Day to Berlin, Arms and Armor Press, London, 1979.

- Collectif, sous la direction du Prof. ULg F. BALACE, Jours Libérés (I)Vol. 19 - F. BALACE, << La nuit la plus courte. .. La liberation de Bruxelles >> - pp. 55-79 Dexia Banque, Bruxelles, 1995

- Collectif, sous la direction du Prof. ULg F. BALACE Jours de Londres, Vol. 16-18, L. A. BERNARDO Y GARCIA, << Tenby ou la genèse des Forces de Terre belges en Grande—Bretagne >> ccl. Dexia Banque, Bruxelles, 2000

- Magazine 39-45, n‘° 184 François de LANNOY, Le général Koenig ed. Heimdaî, Bayeux, 2001

- Magazine Hisioriea, Hors-serie n° 77 Francois de LANNOY, 2Isr Army en Normandie ed. Heimdal, Bayeux, 2003

- Magazine 39-45, n° 209 Carl RYMEN, La Panzerjâger-Abteilung 559 à Limbourg (septembre 1944) ed. Heimdal, Bayeux, 2004