Introduction

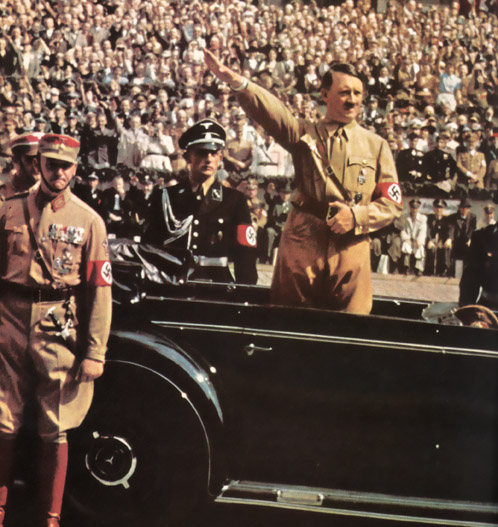

The rise of the Third Reich will be unveiled in this article, the central question being: "How did the Nazis manage to establish a dictatorship in Germany within a short timespan and with little actual opposition from the population?" It is not the intention to describe the history of the N.S.D.A.P. in detail. To that end, reference is made to the specific article about this party.

We will rather be looking at events and ideas that made the rise and growth of Nazism possible. It is remarkable that his occurred specifically in Germany: anno 1900 Germany was one of the most dynamic and progressive countries in the world. The country was considered the European role model for change and growth. Anti-Semitism was no worse than elsewhere in Europe and Germany was a solid and constitutional state. Yet an ideology emerged that would shake Europe to its very foundations. How was that possible?

Images

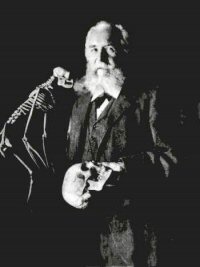

Bismarck

We now return to the era of Otto Bismarck, as the myth of the dictatorial leader which appealed so much to the imagination in the 20s and 30s, is based on him. Moreover, a few elements which would later become important foundations of Nazism, such as anti-Semitism and nationalism, surfaced steadily during this period. In addition, his politics in the second half of the 19th century, characterized by an aversion to socialism, liberalism, the parliamentary system and so on, has sown the seeds of the policy that we see emerging from the 30s onwards.

Otto Bismarck was born on April 1st, 1815, to an aristocratic family of real estate owners in Prussia, the so-called Junker class. During this period, at the Congress of Vienna (following the battle of Waterloo), the European states decided to establish a German Federation, consisting of 39 souvereign states. Supremacy lay with the Austria of Klemens von Metternich. This supremacy came to an end around 1848 due to an outbreak of a series of liberal revolutions in Europe. Within the German Federation, many were dissatisfied as well and they wanted to replace the the Federation by one German state. In the end, this revolution faltered because the most powerful royals and the army - Prussia and Austria - refused to come to an agreement. The German Federation was re-instated.

After his studies, Bismarck embarked on a political career which would ultimately bring him the post of Prime Minister of Prussia in 1862. At the time, Prussia suffered from a major political crisis. The liberals, who were moving forward again after the failed revolution of 1848, blocked the imposing of taxes until Emperor Wilhelm would place the army under supervision of the executive power. This would spell a major disaster however for the financing of the large Prussian military apparatus. By appointing the intelligent Bismarck Prime Minister, who did not shrink back from applying less legal methods, the Emperor managed to put an end to the crisis in his advantage.

Bismarck did not make himself popular in this way at all but that soon changed after the wars against Denmark and Austria in which he mananged to score victories time and again. These wars matched the ambitions of Bismarck who wanted to unify the many small German states into one large empire, naturally under Prussian rule. In this he saw no role for Austria. This led to war between the two countries In 1866 in which Prussia gained the upper hand. With the Treaty of Prague, the German Federation was dissolved. The northerly countries founded the North-German Federation along with Prussia while Austria and her allies, including Bavaria, founded the South-German Federation. As a result of this success in war, the 1866 elections ended in a resounding victory for Bismarck who had been abusing parliamentary rights for four years. The liberals suffered a major defeat. To many people, nationalistic feelings obviously weighed far more heavily than liberal principles, not in the least among liberals themselves.

As a result of the victory over Austria, tension with the French increased. Their political dominance in Europe was threatened by the rise of the North-German Federation, headed by a powerful Prussia. This led to war in 1870, which became known as the French-Prussian war which was won with flying colors by the Prussians in 1871. Bismarck made immediate use of this by entering into negotiations with the South-German Federation. They soon reached an agreement and the German Empire was proclaimed on 18 January 1871.

The constitution of the Second Reich, as the new state was called by some, gave the Emperor and his associates quite a lot of power. Theoretically, the new Reichstag (parliament) possessed more power but it had no authority over the ministers who were directed by Bismarck in his capacity as Chancellor, a function he had created for himself. The army also possessed a high degree of independency. The Minister of War was not answerable to the Reichstag but to the army. As a result of the victories in the wars against Austria and France, the army had built itself an enormous reputation. Militarism within the Empire became increasingly influential and it would even play an important part later on in undermining the German democracy and in the rise of the Third Reich. Bismarck allowed the army to evolve into a state within the state but at the same time, he played an important role in curbing the ambitions of that same army.

That is a remarkable observation for a man who was and still is remembered as a politician who did not shrink back from violence in order to achieve his aims. After the momentous wars in the 60s of the 19th century, Bismarck’s policy was primarily aimed at maintaining peace in Europe. This in order to give the young Germany the opportunity to grow internally and so to achieve a bigger chance of survival. On what is the image of Bismarck as the charismatic and autoritarian leader based then?

That image grew and was cultivated especially from the 20s of the 20th century onwards, based on memories of his inflexible policy against anyone who could be considered an enemy of the Reich. Think for instance of the Kulturkampf (the struggle between 1872 and 1879 against the power of the Catholic Church) and the anti-Socialist laws (for instance the ban on Socialist organisations and meetings). Each of these internal conflicts went with grievous violations of human rights but they did not achieve the results Bismarck had hoped for. Instead of removing the Catholics from politics, they joined forces in the Deutsche Zentrumpartei which would remain extremely loyal to the state. The Socialists gained more and more popularity and just before the beginnnig of World War One, they even became the largest party. As a result of this struggle, German Socialists shifted to the left even more and a deep chasm developed between them and the other civilian parties - read: liberals - which also formed the base of the crisis the Nazis would use to seize power. The middle class and the aristocracy, which later on would constitute the majority of Hitler’s followers, had never accepted the Socialist as a legal political movement. They also held quite a number of positions within the existing administrative agencies, such as the courts and they used this to fight the Socialists. This however could not halt the advance of the left but only deepend the chasm between the various ideologies.

After Emperor Wilhelm II had ascended the throne, Bismarck’s position weakened drastically. In 1890 he was forced to give up all his political functions. The fact that Bismarck’s politics did not always achieve the desired goal soon faded into oblivion in the 20s as attention shifted to his inflexibility and his eagerness to deal with enemies of the Reich.

Images

Growing nationalism and anti-Semitism

These differences and problems did not cause people to develop an aversion to politics, on the contrary, political discussions were held more and more frequently. The discussion about Germany’s place in Europe was a central theme. In the last decennium of his rule, Bismarck had focused primarily on maintaining peace in Europe as he feared that the fledgling German nation would not survive a big international conflict.

The Reichskanzler succeeding Bismarck were not interested in this attitude. When they made up the balance of the political situation in Europe, they saw their own country only as a second class nation after France and Great Britain. Their colonial empire with just a few colonies, especially in Africa, including Namibia, Togo and Camerun was disappointing. In order to create a counterbalance against the British, construction of a large fleet was embarked on. These ambitions were strongly supported by Emperor Wilhelm II himself.

Characteristic at the end of the 19th century was the founding of a large number of nationalistic organisations in Germany. That occurred in connection with the conquered colonies in Africa and the construction of the fleet. One of the most prominent organisations was the Allgemeiner Deutscher Verband (later renamed Alldeutscher Verband) which advocated expansion of German territory in the world and the Arisierung (Germanisation) of national minorities like the Poles in Germany itself, by for instance opposing the use of their native language in schools. Another one was the Flottenverein which would become the largest organisation. It advocated construction of a powerful German fleet and was sponsored, not by any co-incidence, by the armament manufacturer Krupp. These organisations can be seen as a kind of lobbyists that certainly influenced politics.

This increasing nationalism with its inherent ambitions on the one hand and the increasing anti-Semitism on the other cannot be viewed separately. At the end of the 19th century, the Jewish community was a strongly assimilated group which hardly distinguished itself from other Germans, except for its religion. Nevertheless, they were barred from holding higher positions in civil administration. As a result of this discrimination, some 100.000 Jews emigrated but the majority remained because of the economic boom and the industrialisation Germany enjoyed, especially in the second half of the 19th century. Notwithstanding the prevalent discrimination, the Jews were primarily an economically successful group. They also belonged to the more progressive part of society.

The combination of economical succes and the progressive attitude of the Jews was a thorn in the side of the more progressive elements that saw the industrialisation and its inherent modernisations with an unhappy eye. Anti-Semitism was not new in Germany or in Europe for that matter. The entire Christan history is characterised by it: traditionally the Jews were thought to be responsible for the death of Christ. Anti-Semitism, as it was known until then, was primarily aimed at the non-Christian belief of the Jews. At the end of the 19th century however, this also included the racial element.

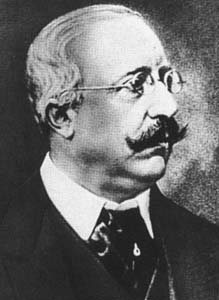

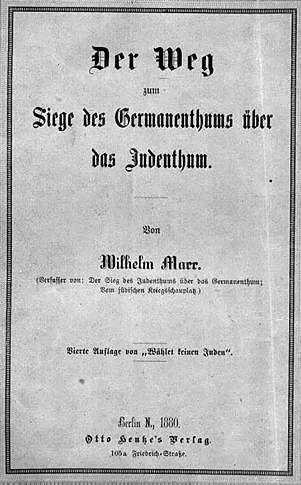

Jews were less and less recognizable as a religious minority. The switch from a religious to a racial discrimination can be placed in 1873 when a certain Wilhelm Marr published a book entitled: "Der Sieg des Judentums über das Germanentum von nicht konfessionellen Standpunkt" (The victory of Jewry over Germanism as seen from a non-confessional standpoint). In it he advanced the thesis that Jews and Germans belonged to different races. In a later book "Der Weg zum Siege des Germanentums über das Judentum" (The road to victory of Germanism over Jewry) he introduced the idea that Germans and Jews were engaged in a prolonged conflict which could only be solved by the disappearance of one of these groups. Assimilation therefore was no solution.

To prevent the Jews from winning, he founded the Antisemiten Liga, the first German organisation that strove for elimination of the Jews from society. A whole series of anti-Semitic authors who gradually gained influence, followed in Marr’s footsteps. And yet, the greater part of German public opinion was opposed to such racism. Proof of this can be found in the very limited and temporary success of the small anti-Semitic splintergroups in the elections. Especially the large working class turned its back on these groups as they were considered undemocratic.

Despite their limited success, the anti-Semites had managed to put the Jewish question on the political agenda. In the last quarter of the 19th century, anti-Semitism had become rather normal. In this context, we can see the term Arian emerge. The French theoretician on races, De Gobineau, in his work: "Essai sur l’inégalité des races humaines" (Essay about the inequality of human races), made a distinction between races, not based on color but on climatic conditions and geographic location. He considered the Arian race as mightiest of all. In itself, there was nothing new about the term Arian: it was an age old notion, referring to a group of people speaking a language of Indo-European origin. New however was the racial connotation that was attached to it from then on: the Arian race that lived on in the Germans could only survive as long as it remained pure. Mixing with other races was unheard of. In his book "Die Grundlagen des XIX Jahrhunderts" (The foundations of the XIX century), Houston Chamberlain blended that idea with social-Darwinism, the application of Charles Darwin’s theory on evolution to humans. Just like in the world of plants and animals, only the fittest will survive, thus the continuation of the human race can only be guaranteed when it rids itself of other, inferior cultures. We can see these ideas very clearly among Nazis. One example is the book "Der Mythos des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts" (The myth of the 20th century) by Nazi ideologist Alfred Rosenberg.

After the First World War, anti-Semitic language gradually grew stronger. In political debates, phrases like "the November traitors" or "the Jewsi Bolshevist conspiracy" were used and increasingly accepted. Although most people still rejected physical violence against Jews, a few eruptions of violence did occur, for instance in November 1923 in Berlin, which are characteristic for the growing radicalism against the Jews.

Images

The notion of Lebensraum and racial purity

Also borrowed from the animal world was the notion of territorial urge, the search for Lebensraum (Space to live). As the Arian race was the superior race, it was best suited to dominate the world. Therefore, it had to expand its territory. Geographer Friedrich Ratzel coined the phrase in 1897 in his book: "Politische Geographie" (Political Geography). It was no co-incidence that precisely in this period, the phrase Lebensraum emerged, popular among many prominent German politicians such as Erich von Falkenhayn, the Minister of War and Alfred von Tirpitz, State Secretary of the navy.

At the end of the 19th century, German industry enjoyed a strong growth and cities blossomed everywhere. This spoiled the rural idea, prevalent in the more progressive circles. By subjugating Slav farmers by means of a war, who were considered an inferior race, more Lebensraum and rural areas would become available. In political circles, thought shifted more and more towards terms of races. Foreign policy should no longer be carried out between states but between races. The interest of the state as such was considered of increasingly minor importance.

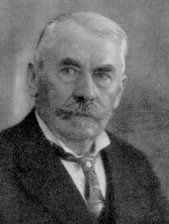

Someone who cannot be left unmentioned in this context is Ernst Haeckel (1834 - 1919). His book "Die Welträtsel" (The riddles of the world), a popularisation of Darwin’s ideas, became an absolute bestseller. He believed in the rightenousness of the extermination of inferior races. From the theory on evolution he drew the conclusion that all aspects of the world have their origin in one and the same essence. In this monism, as this train of thought is known, all possible forms of economics, politics and ethics are reduced to applied biology, a notion we also find amog Nazis. A good example is the principle of Lebensraum. The expansion of living space - read: conquering of territory - was seen in connection with a struggle between races in which the superior Arian race was to supersede the inferior races.

In addition to the idea of Lebensraum, the notion of racial purity was brought into vogue. Not only the inferior races were to be exterminated, the own race had to be purified as well. In the medical world, where the young science of genetics was rising, the policy that took care of the sick and disabled was opposed to. Such a policy would irrevocably lead to a degeneration of the own race. Alfred Ploetz, one of the first eugeneticians, therefore advocated the elimination of the inferior weak. That could be done in various ways: by sending them to the front, by abstaining from treatment of child diseases or to have a medical team decide at birth whether a baby was suitable to survive. In order to promote this view, he founded the "Berliner Gesellschaft für Rassenhygiene" (The Berlin association for racial purity) in 1905 which gradually won influence.

All these elements can be found again in Nazism one by one. Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf that only a Lebensraum of sufficient dimensions could guarantee freedom of existence to people. According to God, the earth had not been reserved for certain peoples. The strongest race was entitled to take possession of the territory. This could only be achieved in battle. For the expansion of Germany, Hitler turned to the East exclusively, to eastern Europe and the Soviet Union as the Arian core had disappeared from the local inhabitants. Moreover, the Soviet Union was ruled by the "international Jew." It was therefore impossible to distinguish between the struggle for more Lebensraum and the struggle between the races that Hitler envisaged. He wrote in Mein Kampf that the mistake should not be made to make the conquered Poles into Germans for instance. Each element, alien to the race, should be eiiminated. It is difficult not to think of Ploetz’s ideas in the numerous experiments the Nazis carrried out on humans to test their genetic theories such as the sterilisation of the mentally disabled and the euthanaisa policy concerning the physically disabled.

We should however not make the mistake to view all these philosophies at the end of the 19th century as one coherent ideology, the final straight course towards Nazism. Those who advanced these ideas without a discernable common denominator were mainly individuals, often with great mutual diffences. Yet, a few of these individuals began founding associations in order to combine the ideas mentioned above. Theodor Fritsch, known by his Antisemiten Katechismus and his Handbuch der Judenfrage (Handbook of the Jewish question), founded the Reichshammerbund in 1912 which was characterised by a fierce anti-Semitism, the urge for a restoration of a rural Germany and the conviction of the superiority of the Arian race. In his work, runic script and the swastika popped up for the first time as signs of the Germanism he idealised so much.

All told, the impact of the philosophies discussed above on government policy remained limited in 1914 but it must be obvious that many people were influenced by them. The influence of these ideas on Nazism are clear: anti-Semitism and racial purity would become the main pillars of Nazi ideology. After the First World War, the ideas about racial purity and social biology gained influence. Among prominent figures in health and welfare organisations, the conviction grew that it was necessary to establish a system to deal with social needs, crime and other deviant behaviour. It was intended to clear German society of this. Society was seen as a body that had to be stripped of all possible parasites and alien organisms. Eperts examined people such as criminals, the disabled, the sick, the so-called asocials and came to the conclusion they suffered from genetic disorders. Because these people formed a financial burden too great for society to bear, measures had to be taken to prevent them from passing on their evil genes. Sterilisation was advanced as a possible solution. This was applied not only in Germany but also in Sweden. However, more voices went up to liquidate these people. An ominous revolution in the medical world.

Images

The First World War

As mentioned before, at the end of the 19th century, a number of nationalistic movements was founded, the Alldeutscher Verband being one of the most prominent. Their ambitons were grand: after an internal cleansing, aimed at the Poles and especially the Jews, Germany was to grab global dominance. In order to realise these ambitions, some of these movements began working together. This was remarkable as up till then they had mainly been fighting each other. Thanks to this co-operation, they expanded their base and the number of their followers, enabling them to exert more pressure on the governemnt from 1912 onwards. The Emperor and his son were not entirely insensitive to the nationalist and anti-Semitic course of these movements.

Did this mean though that they formed the decisive factor in the outbreak of World War One? No, this nationalism was just one of the various elements that played a part in it.

At the beginning of the 20th century, an unstable balance of power existed in Europe, characterised by all kinds of military alliances. These were led by Germany and France, two sworn enemies. The balance was upset by a series of international incidents like the Russo-Japanese war, the crisis over Morocco and the Austrian ambitions concerning the Balkans. The assassination of the Austrian Crown Prince Franz Ferdinand was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back.

After Austria had secured Germany’s support, she presented Serbia an ultimatum, as that country was thought to be responsible for the assassination of the crown prince. The Serbs did not not agree and called on Russia, their traditional protector for help. There are various possible explanations as to why Germany supported Austria. Was it a conscious choice to provoke a war with dominance over Europe at stake? Conclusive evidence for this cannot be found. The spirit of 1914 can probably be explained by a combination of growing nationalism and social Darwinism (the battle of the Germans against the Slavs), widespread insecurity and fear of the future due to the international tension, industrialisation and modernisation of society but also by the optimistic idea that the war would not last for long; the so-called Augusterlebnis (August experience).

This hope had to be abandoned soon. The Germans did not succeed in defeating the French in a swift campaign, as had been intended in the Von Schlieffen plan. The initial quick start of hostilities soon bogged down in static trench warfare. Due to the failure of their plan of attack, the German were faced with a war on two fronts as the Russians meanwhile had launched their attack in the East. The mass slaughter in the trenches soon killed all optimism and idealism among the battling parties. Survival was now the central issue; it also applied to the common civilians. Starvation prevailed in almost all participating countries. Especially in Germany, the situation was extremely critical as she was completely cut off from world trade by the Allied blockade.

This dire situation required the harsh hand of a leader. The military commanders, Von Hindenburg and Ludendorff, the heroes of the battle of Tannenberg dethroned Reichskanzler Hollweg in 1916 and established a military dictatorship. This meant that the objectives of the war and foreign policy were henceforth decided on by the military, that the Reichstag was all but sidetracked and that every form of dissidence (such as pacifist as well as socialist critics) was silenced by means of censorship for instance. At the economic level, total war was proclaimed which meant that the entire economic production was aimed at the objectives of war. All available means were to be deployed in order to win the war. Piece by piece, these measures were also taken by the Nazis later on. In contrast to general belief, Joseph Goebbels was not the first to apply the principle of totaler Krieg.

These measures did not achieve much. The war in the west remained a stalemate, despite massive offensives at Ypre, Verdun and on the Somme. These battles claimed the lives of tens of thousands but not one army could force a decisive breakthrough. On the Eastern front, the Centrals enjoyed more success and pushed the Russians back. Their advance spelled the end of the Czarist regime. The Bolshevist Party, led by Lenin, was a strong opponent of war. The Bolshevists were only strengthened in their conviction by the continous Russian defeats. The October revolution not only got rid of the family of the Czar but also of the liberals who had formed a provisional government. Lenin established a Communist dictatorship characterised by a violent suppression of each and every political opponent, the Red terror. The entire society was based on Communism: abolition of private ownership and religion, imposing a planned economy and so on.

These events became known soon in the rest of Europe and they especially shocked the more conservative and aristocratic classes. In all countries, a strong socialist movement had emerged. The majority of those was moderate-minded and looked at the Communist terror with an unhappy eye. The right wingers equated them with Bolshevists however. The fear of the future that prevailed among many people was further strengthened by these events. In Germany, emotions died down quickly when the Bolshevists asked for negotiations. With the peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk in 1918, Germany annexed large stretches of territory in Russia and as a result, she could transfer her troops to the west. Belief in final victory blossemed once more. An ultimate offensive in 1918 should wrest a decision before the Americans were going to play a really significant role. Initially the Kaiserschlacht, as the spring offensive was called, turned out to be a great success. It was the strongest advance since 1914. Logistical problems, the deploymemnt of fresh American troops and better co-operation between the Allies however, prevented the Germans from achieving their final victory.

After the second battle of the Marne, the balance finally tipped in favor of the Allies. The Central states surrendered one by one, Bulgaria, Turkey, Austria, Hungary and ultimately Germany itself. At the end of September 1918 Ludendorff and Von Hindenburg informed the Emperor that the war was lost. Censorship and propaganda however kept the truth from the German population. Therefore the surrender in November 1918 hit even harder and many people got the idea they had been abandoned and betrayed. The German Reich, of which so much had been expected, had failed. Many looked back in sadness on the autoritarian leader Bismarck under whose leadership, it was assumed, such a thing would never have happened.

Images

The Treaty of Versailles

Yet, the worst was still to come. The last month of the war progressed very chaotically. A revolt of sailors in Kiel spread over the entire country. After the October revolution in Russia, Germany experienced its own November revolution. In imitation of the Soviets in Russia, Raden (councils), made up of workers and soldiers, were set up all over the country. They seized control in most German cities. While everybody was looking for explanations and culprits for the defeat, the spirit of the revolution spread ever further. Radical Communist threatend to seize power. In order to prevent this, the republic was proclaimed on November 9th , led by the socialist Friedrich Ebert. Von Hindenburg managed to persuade Kaiser Wilhelm to abdicate in Germany’s interest as he feared the Allies would refuse to negotiate with the Emperor. Wilhelm reluctantly agreed and went into exile in Doorn in the Netherlands. Following that, the strongest blow fell: the peace terms Germany was forced to accept.

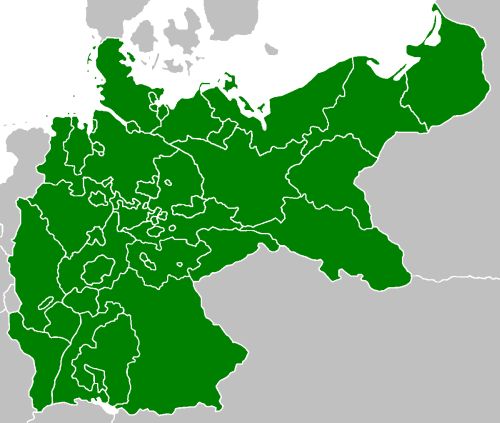

Separate pacts were signed with each of the Central powers. The treaty of Versailles stipulated the peace terms for Germany and those were very rigorous indeed. Germany lost the Elzas-Lorraine region to France, and Eupen, Malmédy and Moresnet to Belgium. The left bank of the river Rhine was occupied by the Allies and the Rhine region was demilitarised. Saarland was placed under supervision of the newly established League of Nations for 15 years after which it was allowed to determine its own fate. In the east, the treaty of Brest-Litovsk was annulled and Germany lost the Danzig corridor to Poland and the Memel area which would ultimately be incorporated in Lithuania. All German territory overseas was placed under mandate of the League of Nations and divided between Great-Britain, France, Belgium and other countries. The German army was reduced to a policeforce of 100.000 men and had to make do without heavy artillery, an airforce and a battle fleet. Later on it was also stipulated that Germany had to pay for the inflicted damage. Article 231 of the Treaty on the question of accountability stipulated that only Germany was responible for the damage the Allies had suffered. Most Germans considered these rigorouss terms a real humiliation, even an unjustified humiliation as many refused to accept that the German army had been defeated on the battlefield.

The idea that Germany had been betrayed by the enemies within was strong among the senior officers and soon spread among the general public. Ebert confirmed this thought on the return of the troops in Berlin, declaring: "It was not the enemy who defeated you." Despite Ebert’s speech, many Germans, especially the right wing politicians, held the new government, led by the socialists responsible for the "stab in the back." Many people in the Allied camp also found the imposed terms extremely rigorous, even too rigorous. In the second half of the 20s, more voices arose to - partly - revise the Treaty, in particular the amount of the repairation payments. One of the great advocates of this was the well known economist John Maynard Keynes who doubted whether Germany would ever be able to repay the astronomous amount of 33 billion dollars. As a result, a policy of appeasement emerged among most European governments, a policy the Nazis exploited extremely well in the 30s.

Images

The Weimar republic: years of crisis

Humiliated, weakend and ravaged by revolution, Germany had to embark on the experiment of a democratic republic.

In the young republic, power lay in the hands of a three party coalition, the Catholic Zentrumpartei, the social-democratic SPD (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschland) and the left liberal DDP (Deutsche Demokratische Partei). Chancellorship was in the hands of the social-democrat Friedrich Ebert. They were faced with huge problems: the famine had not yet been solved and a veritable pandemic of influenza claimed the lives of tens of thousands. A hyperinflation made the already bad economic situation even worse. Besides, the young Republic also had to deal with uprisings.

In January 1919, a Communist group, the Spartakists attempted to unleash a revolution. They hoped for the support of the returning soldiers. The revolution failed because the Freikorpsen, paramilitary units consisting of veterans and young men, sided with the Republic or rather, they chose sides against the Communists. The revolution failed and its leaders Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg were assassinated. The Communist uprising in Bavaria was also suppressed by the Freikorpsen. They numbered some 400.000 members, for whom normal civil life was very arduous. Many were unemployed and they felt very uneasy about the disappearance of the monarchy. They played a vital role in the mood of violence and rancour following the war. When the Freikorpsen were dissolved in 1921, many former soldiers joined veteran organisations. The most prominent was the "Stahlhelm - Bund der Frontsoldaten" (Association of front soldiers). The organisation evolved into one of the largest nationalistic and anti-republican movements in the Germany of the 20s. They also embraced the "stab in the back" legend wholeheartedly. The members appeared in the streets during parades, always in uniform as an expression of their attitude that the battle was still continuing even after 1918. It did not take long before connections were made between such paramilitary units and political parties. These so-called Kampfverbände (fighting units) served as security forces during political meetings, they intimidated opponents and did not even shrink away from murder. Mathias Erzberger for instance, a politician of the Zentrumpartei who had sat at the negotiation table in Versailles, was murdered by members of the Organisation Consul.

More positive was the fact that in January 1919, the first elections in which women were allowed to vote, were held. On February 6th, 1919 the "Verfassunggebende Deutsche Nationalversammlung" (Legislative German national assembly) a constitutional body, met for the first time in Weimar. They did this in order to evade the ongoing revolution in Berlin and so they gave the republic its unofficial name. The new constitution created a republican semi presidential system with a president and a chancellor as active participants in administration. The parliament, the Reichstag, was elected according to proportional representation, i.e. the percentage of seats won is proportional to the percentage of votes. Friedrich Ebert was named the first president and Philip Heinrich Scheidemann the first chancellor of the Weimarrepublic. August 11th, 1919, the constitution was officially signed by Ebert. A remarkable article in the constitution authorised the state president to rule alone in times of unrest and effectively bypassing parliament. This also meant he was empowered to deploy the army to restore order if he deemed it necessary. In principle, this article was meant only for exceptional situations but Ebert used it on no less than 136 occasions. By doing so, he undermined the democratic nature of the republic and created a dangerous precedent.

Nevertheless, the problems were far from over. The hyperinflation went on and on. In less than three years, the Mark had plummeted in value from 9 marks to the U.S dollar to 191 to 1. In November 1923, the absolute low was reached: 4.3 billion marks to the dollar. Due to the bad economic situation, the Republic claimed she could no longer meet the repairation installments imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. Early January 1923, France decided to occupy the Ruhr area to enforce payment. Workers and public officials in the region went on strike in protest. This completely wrecked the German economy, resulting in a massive hyperinflation. Because money had no value whatsoever anymore, goods were the only things of value. A huge crime wave deluged the country. Usurers and black marketeers abused the situation to enrich themselves.

In addition, the political landscape broke into slivers with a number of small extremist (left as well as right) and nationalistic parties. One of the newcomers was the D.A.P. (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, German Workers Party). Initially, this small party was hardly noticeable in the political arena but it would gradually evolve into the N.S.D.A.P. (Nationalsozialistiche Deutsche Arbeiter Partei, Nationalsocialist German Workers Party) of Adolf Hitler. The unrest and unhappiness among the population became clear in the elections of June 1920 in a resounding defeat for the Weimar coalition. The percentage of votes for the S.P.D., Zentrumpartei and DDP dropped from 76 to 46 percent. Owing to the electoral defeat of the ruling coalition, it was no longer possible to form a majority government, seriously narrowing the margin for new cabinets. The minority governments that took charge after 1920 - 20 different cabinets between February 1919 and January 1933 - frequently ran into problems. Yet we must not overestimate the instability of the governments of the Weimarrepublic. Despite the frequently changing cabinets, some departments enjoyed a long lasting continuity. Gustav Stresemann for instance was Minister of Foreign Affairs for six years. It goes withourt saying that so many changes in government did not imbue the population with much trust in the Republic.

Besides, there was also no love lost between the Republic and the army and the public officials who found it difficult to adapt to the new structure. The lack of loyalty of the army was evident during the Kapp-Lüttwitz putsch. In March 1920, orders were issued to dissolve "Marinebrigade Ehrhardt." The commanders, supported by Wolfgang Kapp of the Deutsche Vaterlandpartei (D.V.P.) and General Walther Freiherr von Lüttwitz refused to obey the order. The brigades marched on Berlin and President Ebert was forced to flee the city. Army commanders in other parts of the country also supported the putsch and that seemed to be the end of the young Weimarrepublic. A general strike, organised by the trade unions, saved the democracy however. Kapp, who meanwhile had proclaimed himself Reichskanzler and Von Lüttwitz did not succeed in making their authority felt. After a few days they fled the country. The putsch had failed, thanks to the workers and not to the Reichswehr which had refused to offer its support to the Republic. The army, commanded by the rightist general Hans von Seeckt was and remained a formidable opponent to the Weimar government. This bode no good at all for the future.

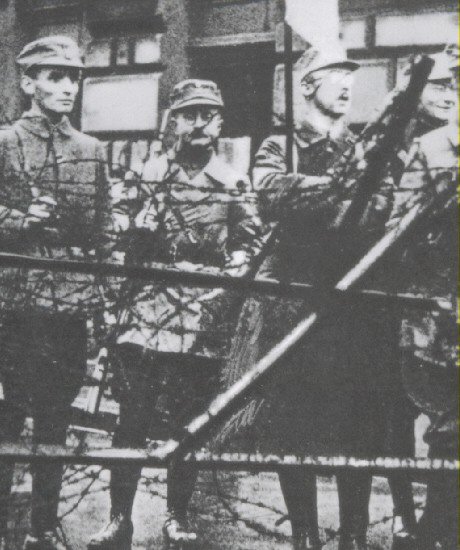

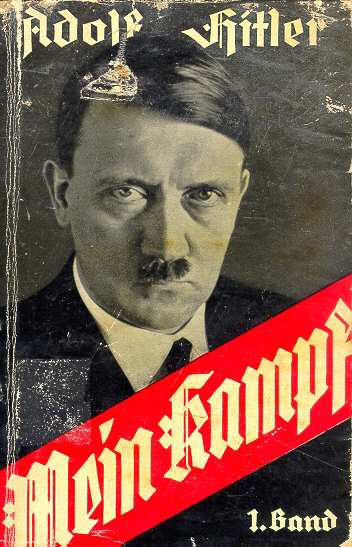

The political violence reached a new high in 1923. A Communist uprising in Hamburg for instance was bloodily suppressed. The best known action was the "Bürgerbräukeller" putsch in Munich. Some time earlier the "Kampfbund" had been established in Bavaria, a league of patriotic groups including the N.S.D.A.P. of Hitler, the "Bund Oberland" and the "Reichskriegsflagge". The SA, the paramilitary organisation associated with the N.S.D.A.P. took part in it, just like the WW 1 general Ludendorff. They planned a coup d’état in the federal state of Bavaria in order to oppose the Weimarrepublic from there. The putsch failed however and a few of the leading players like Adolf Hitler and Rudolf Hess ended up in prison. The influence of this event can hardly be underestimated. Hitler did not achieve his primary goal but at his trial, which was frontpage news nationwide, he made an impression with his talent as an orator. This meant a veritable propaganda victory for the Nazis. During his stay in prison, he wrote his famous Mein Kampf.

Images

Mein Kampf, the ideology of Nazism

Hitler was sentenced to five years imprisonment but he remained in jail for only 10 months. He was released on 20 December 1924. During this period he had written the first volume of Mein Kampf, entitled "Eine Abrechnung" (A settlement). The book was published on 18 July 1925. A year later, the second volume "Die Nationalsozialistische Bewegung" (Nationalsocialist movement) was published.

The work contained all important pillars of the nationalsocialist party. Radical anti-Semitism is one of them. In Mein Kampf he calls the Jews "Hebrew spoilers of the people" who had caused the defeat of the German army during World War One. If these "traitors, black marketeers, usurers and embezzlers" had been exterminated, it would have saved the lives of thousands of "valuable" Germans. This idea strongly appealed to people as it matched the "stab in the back" legend and the inflation of the time which had enabled usurers to make huge profits. The question is often asked where Hitler’s anti-Semitism stemmed from. As mentioned above, anti-Semitism was present all over Europe but it was especially strong in Germany. Hitler grew up in a culture in which anti-Semitism was considered all but normal. Apart from that, he had spent a few years in Vienna where he became familiar with the all-German train of thought of Georg Ritter von Schönerer and he had become an enormous fan of Richard Wagner’s music. This composer was known as a rabid anti-Semite who had written an essay about "Das Judentum in der Musik"(Jewry in music), accusing the Jews of not adapting to Germanic culture. Germanic legends and myths also played a central part In his operas. Hitler also strongly admired Mayor Karl Lueger, a fervent anti-Semitic demagogue who defended the thesis that a conspiracy existed between Jews and Marxists.

The anti-Semitic ideas Hitler already embraced, really rose to the surface after World War One. Germany’s defeat was a real shock to him. He was firmly convinced Germany had been betrayed. He soon saw the Jews, who he did not trust anyway, as the culprits. This became the central theme in all his speeches: the once so mighty Germany had been humiliated, weakend and betrayed by leaders who had cowardly surrendered the fatherland to mighty enemies. Those same enemies, and behind them the Jews, had the war and the revolution on their conscience. All social, economic and political problems could be traced back to this one source: the Jews. The only way to solve this problem was to eliminate the Jews from society. It included all Jews, so not only those practising the religion but anyone of Jewish descent, regardless of their belief. This elimination or extermination, as Hitler called it, was accompanied by violence from the beginning.

Hitler’s battle against the Jews is connected to his vision of the phrase race. In this he stood diametrically opposite the socialists and Communists who divided society in mutually opposing classes, e.g. the proletariat versus the bourgeoisie. Hitler on the other hand, fostered a racial vision: a struggle between races instead of classes. Different races existed among people with one subordinate to the other. This way he saw the Arians as superior while the Jews were no more than a race of parasites attempting to destroy their host from within. The stronger race was to try and exterminate the weaker in order to prevent going down itself. Blending of the two races was certainly impossible. For a race to survive, racial purity was an absolute requirement, just as sufficient Lebensraum was.

Hitler’s anti-Bolshevism originated from his anti-Semitism. Marxism, Bolshevism and Jews could not be viewed separately. In Hitler’s opinion, Marxism and Bolshevism were a Jewish invention, a sort of evil illness they wanted to spread among the Arian race. The German race needed more Lebensraum and this was to be achieved in the East. Over there, the Jewish-Bolshevists were in power and by dealing with them, he would kill two birds with one stone: more Lebensraum for the Germans and the extermination of the Jews who were in charge in the East. In this we see a clear example of social-Darwinism. Hitler saw international relations as a lasting racial conflict.

In order to be able to realise this, Germany had to renounce the Treaty of Versailles. In this way the country could rearm itself and focus on a war of conquest in the East. Before she could embark on this however, Germany had to be changed internally. Therefore the weak and internally divided Weimar Republic had to be dealt with. After his failed putsch, Hitler realised that a coup was not the correct way to seize power. He obviously needed more support from people in key positions in the existing order. He had paid too little attention to this in 1923 but he was not going to make that same mistake twice.

One by one, these ideas can not be viewed separated from Hilter’s nationalism. In imitation of the Schönerer mentioned earlier, Hitler had taken up the idea that the German speaking parts of Austria had to be added to Germany. In order to emphasize this nationalism, the Nazi party adopted a few old habits and customs. National traditions should be re-instated. The N.S.D.A.P. promoted a reform of German society and chose a return to the more orderly, simpler way of life of the past. Nationalism surpassed all classes and should lead to a national culture. Many people did not feel at all well within the "modern" Weimar Republic. The emergence of the tabloid press, new means of communication like the radio and the cinema, new forms of music like jazz and swing and modern art were considered by many to be a threat to the traditional cultural values. They felt order and discipline had been pushed aside by a more questionable morale, characterised by sexual and cultural freedom. Just like Hitler did, they saw the Republic as a degenerated broth of what once had been a famed Empire at the time of Bismarck.

The key to nationalsocialism lay in the notion of the Volksgemeinschaft (People’s society) which replaced the divided society (Gesellschaft) of the industial nation. The Volksgemeinschaft was an all encompassing community which regulated the lives of all individuals within. It was a mass community in which the earlier distinction based on for instance class, was replaced by the equal participation of all individuals within the community. The final result was that the nationalsocialist ideology demanded a total reform of German politics and culture whereby the community (in theory but in practice the state) controlled each and every aspect of the life of the individual. That idea forms the base of the slogan "Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer" (One nation, one state, one Führer). The Nazis wanted to create one nation within a larger state so to speak, directed by one man, Hitler. Nationalsocialism was aimed at penetrating the life of the individual by creating an organic society where everyone and everything was controlled and co-ordinated by the party as she was the guardian of the Volksgemeinschaft.

Mein Kampf was certainly not an immediate success, on the contrary; until the elections of 1928, only 4.000 volumes had been sold. From 1930 onwards, the time of the electoral breakthrough by the Nazis, sales rose dramatically. During the Third Reich it became an absolute bestseller. It was almost considered treason if one did not possess this book.

Images

The golden years 1924 - 1929

From 1924 onwards, the Weimar Republic enjoyed a period of relative rest and a steady growth of prosperity. Gustav Stresemann, the chairman of the D.V.P. played an impotant role in this.

In the middle of the Ruhrcrisis, Stresemann was appointed Chancellor of the Weimar Republic. A bizarre choice as he was known as an aggressive German nationalist, a fervent opponent of the Treaty of Versailles and a follower of the Emperor. As chancellor, he chose an entirely different route: he urged Germany to meet its international demands (make the repairation payments) and he strove for good relations with the Allies. In this connection, the Treaty of Locarno was an especially important step. This treaty was signed by Germany, France, Belgium, Great-Britain and Italy. The first three countries agreed not to attack each other, the other two acting as supervisor. Should one of the first three countries attack another country, the others would support the latter. Despite this treaty being rejected by German nationalists, Stresemann managed to guide Germany into membership of the League of Nations.

This peaceful policy did have a dark side however. Stresemann used his position in the League of Nations to fight the rigorous limitations imposed on the German army. He was of the opinion that the other great powers should impose similar rigorous limitations on themselves as well. This demand was unacceptable to the former Allies but it did pave the way to justification of German rearmament in the future. As Minister of Foreign Affairs though, Stresemann knew all too well about the secret pact with the Soviet Union. Germany possessed excellent equipment and had the engineers and the expertise for the production of armaments. The Soviet Union desperately wanted modern weaponry but she had neither the factories, the machines and the know for production, nor the money to buy weapons or expensive machinery. From the beginning of 1921 and in utmost secrecy, contacts were made between the leaders of the new Reichswehr and the Soviet Union to find a joint solution to their problems. On 7 April, 1921, Leon Trotski, People’s Commissioner and founder of the Red Army, received a report from his contact in Berlin, Kopp. It concerned a project that had been developed together with German officers. The project provided for construction of airplanes by the Albatroswerke, U-boats by Blohm & Voss and cannon and shells by Krupp. The project was indeed carried out from 1922 onwards. The secret was well kept until after the Second World War. Ii is clear that both the Red Army and the German Reichswehr were partly being expanded and trained in this period of co-operation.

The dualism in Stresemann’s politics can be explained by his realistic attitude, inspired by Bismarck’s Realpolitik. Stresemann was a nationalist who dreamt of a strong Germany. He was far from being an advocate of the Weimar Republic but he realised there was no better alternative at hand. He can best be described as a Vernunftrepublikaner, someone who accepted the Republic as the lesser of two evils.

In the interior, Stresemann managed to halt hyperinflation. He negotiated the retreat of French and Belgian troops from the Ruhr area, provided Germany resumed its repairation payments. The negotiations resulted in the so-called Dawes plan. This meant that the occupation of the Ruhr area was lifted and also included a number of measures making the repairation payments easier to afford. It also enabled Germany to contract foreign loans, especially in the United States. At the same time, the Stresemann government introduced the Rentenmark to replace the Papiermark that had totally devaluated. Owing to the measures taken by the Reichsbank, headed by Hjalmar Schacht, to protect the Rentenmark against speculation and as the currency gradually became more readily available, the population accepted this temporary currency and the hyperinflation was halted. On 24 August 1924, the definite currency was introduced, the Reichsmark.

Especially owing to the foreign (read: American) loans, the economy gained a new lease on life while the political situation was stabilised. A period of relative prosperity emerged. There was renewed security about the value of money. People needed to fear no longer that prices would be doubled the next day. Confidence in the Weimar Republic grew slowly. Confidence in the future was also strengthened when the popular war hero, Paul von Hindenburg was elected President. He was no advocate of the Republic but he strictly adhered to the constitution. In the long run, Von Hindenburg’s election was a disaster for Germany. As his tenure progressed, he became more and more convinced that the monarchy was the only legitimitate administrative system for Germany. Power within the Republic thus lay in the hands of someone who did not believe in democratic values and who had no intention whatsoever to defend them against possible enemies. This became clear at the beginning of the 30s.

In any case, this period of relative economic prosperity and political stability was called the Golden Years of the Weimar Republic. It is therefore no coincidence that extreme parties experienced little growth in this period. That also applied to the N.S.D.A.P. In the elections for the Reichstag in 1928, the Nazis won only 2.6% of the votes and had barely 12 representatives in parliament. Hitler may have had a great reputation and quite a number of spectators during his speeches but most Germans seemed to give the existing government the benefit of the doubt.

Yet the Weimar Republic remained a fragile entity. It was characteristic that these Golden Years were largely attributable to one man, Gustav Stresemann. Also, paramilitary organisations like Stahlhelm succeeded in expanding their influence and spreading their anti-republican ideas further. At beginning of the 30s, Stahlhelm counted more than half a million members, making it the largest Freikorps.

Images

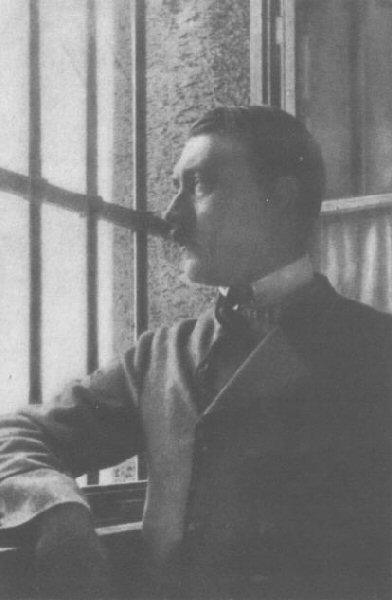

The downfall of the Weimarrepublic 1929 - 1933

The year 1929 proved a radical turn about in every aspect.

Thanks to a new strategy, the N.S.D.A.P. enjoyed an obvious growth for the first time. The party paid much more attention to local politics and to the farming community, the small landowners as well as the large ones. Later on, the emphasis shifted to the middle class. This new work method gained success quickly: the Nazis won the municipal elections in Coburg for the first time. Participation of the N.S.D.A.P. in the protest movement against the plan Young also gained electoral success. Together with the D.N.V.P., Stahlhelm and the Alldeutsche Verband, the N.S.D.A.P. formed the so-calle Harzburgerfront. This front was initially targeted against the plan Young (concerning a decrease of the repairation payments, not its abolition though), but it was clearly anti-republican also. The campaign was no immediate success but it won the N.S.D.A.P. a lot of publicity. Hitler rose in esteem as he was a member of the organising committee.

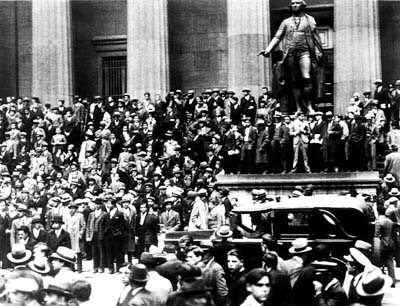

In the economic field, 1929 was an absolute disaster. In the 20s, the world economy enjoyed an enormous growth but especially the United States. The market price of shares was rising and kept rising. There seemed to be no end to the growth. More and more investors wanted to benefit as well and got themselves loans from banks in order to buy shares. The massive growth turned out to be an economic soap bubble because on the stock exchanges, the shares were impossibly overrated. On 24 October 1929 the bubble burst and shares plummeted in value. This caused enormous panic among investors who desperately attempted to sell their shares and obligations, causing the rates to cave in completely. Many lost almost everything they owned and were no longer able to repay their loans. This caused even banks to go broke. It resulted in a snowball effect causing the worsening economy to head for a recession (negative economic growth) fast. Owing to her leading position in world trade, the United States dragged the entire world down with her into an economic crisis.

As Germany had many unpaid loans in America, the country was hit extra hard by the crisis. There was no more foreign capital available and industrial production dropped by about one third. The number of unemployed soared to over 13 million. The Weimar government failed miserably to find an answer to this crisis. The population lost all faith in it and looked for answers in the extreme left (KPD) and exterme right parties (N.S.D.A.P.). Not by coincidence, the Communists too enjoyed a strong growth in this period. The Soviet Union, which had abolished capitalism, seemed to be immune to the crisis, thanks to its planning over multiple years. Even the Nazis adopted this idea when they introduced their Four Year Plans.

The KPD, led by Ernst Thälmann attempted to mobilize as many of these unemployed as possible for their political aims. The party considered this crisis the end of the capitalist system and organised large and often violent demonstrations and protest marches to hasten this demise further. Their actions drove the more prosperous citizens and the middle class straight into the arms of the N.S.D.A.P. which continued defending the right on private ownership.

In 1929, Gustav Stresemann passed away, the leading figure in the last years of the Weimar Republic. Without its leader, the D.V.P. left the government. From that moment on, not a single government enjoyed a majority in parliament. Heinrich Brüning of the Zentrumpartei became the new chancellor. He advocated a return to the Bismarck system. He wanted to diminish the power of the Reichstag and began to limit the freedom of the press. He attempted to halt the economic crisis by lowering government expenditures such the unemployment allowance. A counterproductive argument: in such an economic crisis the government should invest even more. Due to the loss of the American capital this was not so obvious. Moreover, Brüning was afraid that if expenditures by the government rose too much, this might lead to a hyperinflation like Germany had known after the First World War. Brüning’s measures led to an even greater poverty. He earned the nickname the hungerchancellor.

The dramatic economic situation and the bad measures by the Weimar government were a present the Nazis accepted all too gladly. During the next election campaigns, Hitler strongly emphasised the injustices in the Republic. Without advancing real solutions himself, he painted his audiences a picture of a unified and strong Germany. While the situation was nearly hopeless for many people, Hitler offered a message of hope. To many, Adolf Hitler became the strong, energetic leader who would relieve the country of its misery. Thanks to the well oiled propaganda machinery of Joseph Goebbels, this message could be heard all over Germany. The Nazis also adapted their use of language to the target groups. When they spoke to industrialists, they abstained from their anti-Semitic language. This way the party became more respectable and acceptable for the citizens in the higher and middle classes. The elections of September 1930 resulted in a huge victory for the Nazis: they received 6.4 million votes and won 107 representatives in the Reichstag.On the other side, the K.P.D. also made progress. Both parties were diametrically opposed to each other and continuously attempted to disturb each other’s partymeetings. This led to violent engagements more than once, often resulting in deaths. Especially in times of elections, skirmishes like that were the order of the day. This is characteristic for the increasingly radical way in which politics was conducted in Germany. Almost every session of the Reichstag boiled down to vulgar name calling in which both K.P.D. and N.S.D.A.P. continuously showed their disdain for the institution. The centerpoint of power many lay in the hands of Reichspräsident Von Hindenburg. He was already 84 years old and his tenure would end in 1932.

Presidential elections were held resulting in an all out confrontation between left and right. Hitler had put himself up as a candidate too. The strange result was that Von Hindenburg became the candidate of the left almost automatically. He was in no way whatsoever a follower of left. Just because he was the only one who could stand up to Hitler, he received support from the socialists. In spite of this support and that of the Catholic Zentrumpartei and the Liberals, Von Hindenburg just failed to reach a majority (49.6%) in the first round of voting. Hitler won 30%. Thanks to the so-called Deutschlandflug, when Hitler crisscrossed the country by airplane to deliver speeches, his number of votes increased to 37% in the second round. That was not enough however to defeat Von Hindenburg who won 53%. Hitler lost but these elections made it very clear that the Nazis were the strongest party and movement in Germany. Thälmann and his K.P.D. came nowhere.

Von Hindenburg appointed a personal friend, Franz von Papen Reichskanzler. He conducted an autoritarian rule but his government had little support in parliament and among the population. His cabinet was mockingly called the cabinet of barons as most of its members belonged to nobility and were not connected to any party. Von Papen did receive support from Kurt von Schleicher. He was the strong man in the German army and was appointed Minister of Defense. Both Von Papen and Von Schleicher were opponents of the Republic and wanted to return to the autoritarian hierarchy of the ancien régime. They wanted to gain Hitler’s support for their policy. To this end, the ban on the SA, imposed by Brüning, was lifted. Instead of calming the moods, this led to a new wave of violence with the Altonian bloody Sunday a sad climax. Near Altona in Prussia a large street brawl ensued between the SA and the Communist which led to 18 deaths.

Von Papen accused the Prussian federal government, one of the last democratic bastions against Von Papen (and Hitler) that they were unable to maintain order. The Reichskanzler persuaded Von Hindenburg to issue a decree. According to this, the Prussian government was dissolved on 20 July 1932 and its authority was transferred to Von Papen. This Preussenschlag spelled the end of democracy in Germany. The freedom of the press, restricted already, was restricted even further. The Nazis watched these events all too happily because in this way their opponents were eliminiated one by one. This became clear in the Reichstag elections of July 1932. The N.S.D.A.P. doubled its number of votes to over 13 million (37.4%) making her the largest party. The Nazis could certainly not attribute this to well worked out solutions for the crisis as they did not have any. Many voted for the N.S.D.A.P. out of dissension with the prevalent chaotic situation in all spheres.

To Hitler, these elections formed the token that it was time to seize power. He did not want to take part in a government if he would not be named Chancellor. Both Von Papen and Von Hindenburg refused to give in to this. This was a defeat for the Nazis which was confirmed in the new Reichstag elections in November 1932. They won a mere 196 seats against 230 a few months before. Von Papen did no longer enjoy the support of Von Schleicher and the army and was forced to resign. Von Schleicher was named the new Chancellor but he too enjoyed little support. Especially Von Hindenburg distrusted Von Schleicher. As Germany had returned in the mean time to the situation in which the head of state appointed the government, Von Schleicher was not granted the time to fully exploit the decline of the Nazis. He had to attempt to master the chaotic situation in Germany as soon as possible. In this he failed. Meanwhile behind his back, negotiations were going on in full swing to get Hitler appointed Chancellor. This was Von Papen’s idea, who still enjoyed the trust of Von Hindenburg and who wanted to settle his account with Von Schleicher. Von Hindenburg, who had no stomach for Hitler at all could reconsile himself with this idea because Von Papen was convinced that he, as vice-Chancellor could restrain Hitler. On 30 January 1933, Adolf Hitler was inaugurated as Reichskanzler. It was the beginning of the Third Reich.

Images

Information

- Article by:

- Gerd Van der Auwera

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 21-02-2016

- Last edit on:

- 14-06-2020

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Sources

- HAFFNER, S. Pruisen. Deugden en ondeugden van een miskende staat. Amsterdam, 2004.

- PIERIK, P. Hitlers Lebensraum. De geestelijke wortels van de veroveringstocht naar het Oosten. Soesterberg, 1999.

- WIEST, A. De geschiedenis van de Eerste Wereldoorlog. Aartselaar, 2002.

- HOBSBAWM, E. Een eeuw van uitersten. De twintigste eeuw 1914-1991. S.l., 1995.

- VERMEER, W. Duitsland, 1918-1933. Vervangen artikel op www.go2war2.nl

- Nazi-Duitsland

- Otto von Bismarck

- Alfred Hugenberg

- De nazi's en de medische wereld

- Bio-ethiek en nazisme

- Weimarrepubliek

- Weimarer Nationalversammlung

- Lebensraum

- Wilhelm II

- Wilhelm Marr

- Het Arische ras

- Franz von Papen