Tannenberg Memorial

Part of a nation’s identity exists of a shared history. How people regard this subject varies per generation. Monuments express the zeitgeist, built to commemorate historical events, and symbolize the past and national identity.

Hero worship

In today’s Germany, people in general do not commemorate military acts of heroism, heroic personages or memorials. These types of hero worship do not longer suit the 21st century. People are rather pacifistic and tend to commemorate victims of the persecution and other acts of violence. This is not incomprehensible given the horrific events of the Second World War. Six decades before that, however, people thought very differently regarding this subject. To die for the country was tragic yet honorable. It is not surprising therefore that many memorials were erected to honor victorious battles, military leaders, and fallen soldiers. The Tannenberg memorial is such a monument.

In "Het bouwen in het Derde Rijk" ("Engineering in the Third Reich") written by G. Troost and published by Uitgeverij Westland in 1943, we can learn the following about the Tannenberg memorial. It is a perfect expression of the zeitgeist.

A united nation honors the memory of those who died for the community. During the years following the war, the ‘Volksbond voor de verzorging van Duitsche oorlogsgraven uit den wereldoorlog’ (People's Union for the care of German wargraves’) erected memorials for the front line soldiers in expansion of its tasks of looking after the soldiers’ graves from the war. These memorials expressed the reverence of the whole community for those who died during the war. The Tannenberg memorial, designated an Imperial monument by the Führer, proves how such a communal remembrance can be realized in a special local landscape such as East-Prussia. But it also proves that the national socialist philosophy was the first to create the conditions for such a significant monumental construction of these types of memorials. It used to be inevitable that the noise of daily life and the irreligious warts of tourist traffic could be heard even below the walls and towers of the Tannenberg memorial. In the new Germany, the grand Totenburg Tannenberg received great prestige. The landscape was significantly opened up and the memorial itself elevated. At the foot of the hill lies a lake surrounded by meadows and woodlands typical of East-Prussia. In the direction of the World War’s battlefield the forest is laid bare and against its backdrop one can find its mountainous area, for whichy such fierce battles were fought. Now, no noise can disturb the peace of the dead anymore. In sacred silence and loneliness, the Totenburg is positioned in the wide Eastern landscape where the great field marshal rests among his soldiers.

East Prussia

The memorial was erected in memory of the battle of 1914. The Russian and German armies clashed with each other during the battle that would last five days and resulted in a prodigious victory for the German army. 92.000 Russian soldiers were taken prisoner and 50.000 were wounded or killed.

Yet, first we need to understand what East-Prussia exactly meant. One who tries to search a map for its location today would be disappointed. It is important to understand that the European borders were subject to modification during the 20th century. Between 1871 and 1918, Germany, also known as the "Kaiserreich", was a monarchy that verged on approximately the same western borders familiar to us today. However, the country’s territory to the east in the direction of Russia was significantly larger. The former Schlesien (Silesia), Posen, East- and West-Prussia were located in what is nowadays Polish and Russian territory. After the defeat following the First World War a significant proportion of these areas were assigned to Poland. In total, Germany lost over 70.000 acres, or 1/8 of its territory.

East-Prussia continued to exist as a German province in the shape of a small area bordering on the Baltic Sea, but separated by Polish territory. This caused a lot of debates during the 1930s since Germany refused to accept its loss, partly because of a sizable number of ethnic Germans still remaining. This resulted in Germany’s quest to reconquer the territory in 1939 and subsequent the Second World War. After 1945, the area permanently belonged to Poland. Its residents are mostly Polish, and only its buildings still betray traces of German origin. Discussion closed, one is likely to think but occasionally, it erupts again like in 2004, for instance, when a few Germans demanded a compensation for expropriated possessions in the former German provinces. Another discussion still going on pertains to the 12 to 18 million German inhabitants who were dislodged.

The area of the battle and the memorial are located in today’s Poland. The country grew in size after 1945 due to its successes in annexing German territory. Yet it had to yield a bigger proportion of its eastern territory to Russia. Poland’s size shrunk with 20% which was more or less reoccupied by the communist country of Russia. Still remarkable, since the Second World War officially started in 1939 because Germany attacked Poland. Not until 1989 could the Polish residents enjoy the freedom which other countries were able to celebrate since 1945.

Hindenburg

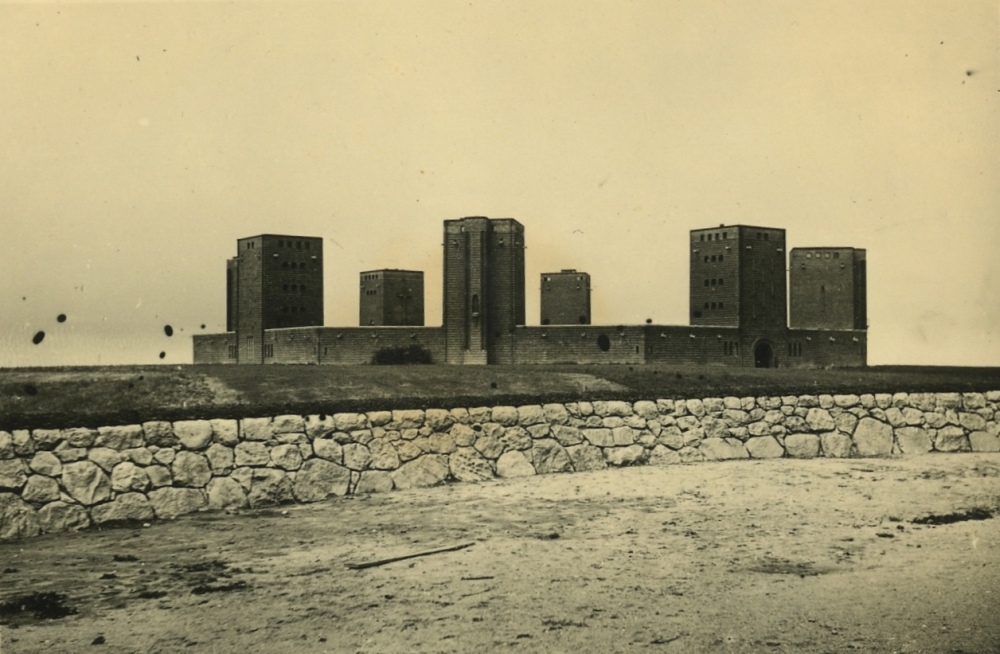

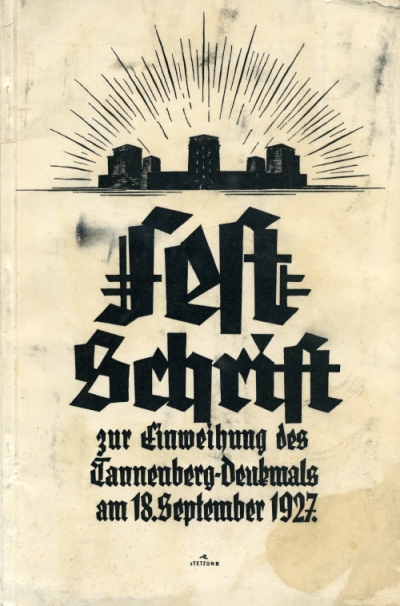

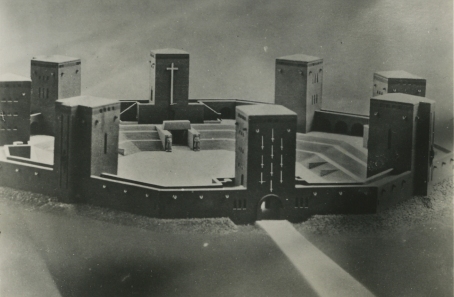

The Tannenberg memorial took the form of an octagon with towers on each corner with an average height of twenty meters. These towers offered a clear view on the battlefield and were connected to walls that surrounded the courtyard. In its midst stood a large cross surrounded by twenty graves of unknown soldiers. Memorial tables were dedicated to the forces that had contributed to victory. On September 18, 1927, after three years of building, the memorial was inaugurated by Paul von Hindenburg, the Reich’s president of the Weimar Republic. After his death in 1934 it would also become his mausoleum. Commanded by Adolf Hitler, Von Hindenburg was buried along with his wife, who died in 1921, in the complex which was intentionally rebuilt. A fitting location as Von Hindeburg was born in Prussia and, with his victory at Tannenberg, received the status of being its liberator. Yet his last will read differently: he had preferred a service in the Garnisonkirche in Potsdam and to be buried on the Neubeck estate, where he was born.

The complex soon became a tourist attraction, as can be concluded from the many photographs present in the German soldiers’ photo albums. This images in this article are also taken from these albums. After Hindenburg’s death Hitler could act without obstruction. The last obstacle to a totalitarian regime vanished due to natural courses. Von Hindenburg was honoured by means of coins and post stamps while the tentacles of the Third Reich penetrated further into society. The letter with Von Hindenburg’s post stamp now could be subjected to a critical inspection that could end with the author being thrown in jail or in a concentration camp. All the while the Reichsmark with Von Hindenburg’s portrait was used to purchase weaponry in preparation of a new war. On the same day, the Wehrmacht pledged its oath to Adolf Hitler, the new Reich’s president and Reich’s chancellor. What formerly required two different persons and functions now became a new Führer with unlimited power.

In April 1945 the Russian army reached Prussia, driving fugitives in front of them. The coffins of both Hindenburg and his wife were transferred in time to Germany to be reburied in the Elisabethkirche in Marburg later on, where they still are today. The remaining objects from the memorial such as banners were also transferred. Yet these objects are still missing.

The coffins of Hindenburg and his wife. In the background we can read the passages ‘die Liebe höret nimmer auf’ and ‘sei getrue bis in der Tod’. Source: Maurice Laarman Collection

Remains

When the complex was vacated the retreating Wehrmacht blew up the towers of the memorial. Hitler commanded to blow up the entire complex, yet there was a lack of sufficient explosive. After the war had ended, the Germans expelled, and the borders determined, the Polish stumbled upon a damaged memorial on their territory. They were not happy with a symbol of the Germans, who they so excessively despised. Consequently, the remains were demolished in 1948. The remaining material was very welcome during this period of shortages and was used to build some of the edifices in Warsaw.

Until the 1960s the ruins were easily recognizable. Nowadays the territory is a nature reserve which features some remaining stone foundations hidden beneath the grass. The nearby town is called Olsztynek, formerly called Hohenstein. The Tannenberg name appears disparately in current Polish history, however. During medieval times, the year 1410 to be exact, the German order of knighthood and the Polish King, who was supported by the Duke of Lithuania, fought each other. The latter was led to victory, and the Polish-Lithuanian empire experienced a period of prosperity. Each year the battle is being commemorated or celebrated with jousting and festivities.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

- Weimar Republic

- Name for the German republic from 1919 until 1933. Hitler ended the Weimar republic and founded the Third Reich.

Information

- Article by:

- Maurice Laarman

- Translated by:

- Mariska Buurlage

- Feedback?

- Send it!