Introduction

Vyacheslav Molotov was one of the most powerful men of the Soviet Union. He was Prime Minister of the Soviet Union from 1930 to 1941 but Molotov has become known most of all as the People's Commissioner for Foreign Affairs, a post he held for 13 years. When he accepted this post in May 1939, he had no experience whatsoever in the field of foreign policy but he proved to be gifted. Friend and foe alike acknowledged Molotov as an exceptionally talented diplomat. Although his contempories described him as a dull, opinionated and self-centered bureaucrat, at the same time he could display a casual ruthlessness towards the victims of the Stalinist regime. As intimus and confidant of Joseph V. Stalin, he played an major role in the terror regime that characterised the Soviet Union under Stalin. He readily admitted later he had put his signature to countless death sentences. In particular, Molotov owed his succesful career mainly to his unconditional loyalty to his mentor Stalin, something which applied to many other prominent Soviet politicians. For a long time, Molotov was considered Stalin's possible successor and he continued defending Stalin's controversial heritage fervently until his death in 1986.

Definitielijst

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Images

From editor to Prime Minister

Molotov was born March 9th, 1890 as Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Skryabin in the village of Kukarka in the Russian district of Vyatka (today the town of Sovetsk in the province of Kirov). Vyacheslav was the ninth out of 10 children of which three died at an early age. His mother came from a rather wealthy familiy that ran a busy grocery store; Skryabin senior worked here as a shop assistant.

Young Vyacheslav Skryabin started his secondary education at a grammar school but did not graduate. Subsequently he enrolled in a Realschule, a modern secondary school in Kazan, 124.27 miles to the south. Here Skryabin became politically engaged and in 1906 he became a member of the Bolshevist wing of the Russian Social-democratic Workers Party. In 1909, shortly before graduation, the youmg Bolshevic and two of his friends were arrested for revolutionary acts, expelled from school and banished to Vologda for two years. In 1910, Skryabin was allowed to take final exams as an external student, enabling him to take his secondary school certificate. In 1911, Skryabin moved to Petrograd (St. Petersburg). Officially he enrolled as an economy student at the Polytechnic Institution but in reality he continued his clandestine revolutionary work and in this way he could avoid conscription after World War One had broken out.

In 1912, Skryabin helped Lenin set up his party organ Pravda (The truth) and he became a member of the editorial staff of the new paper. Another dedicated Communist who also worked for Pravda in this period and with whom Skryabin became friends rather soon, was Joseph V. Stalin (Bio Stalin). In 1915, Skryabin took his pseudonym Molotov, derived from the Russian word for hammer, molot. He thought the word had an industrial and proletarian connotation. At the time, pseudonyms were very popular in Bolshevist circles and Lenin, Stalin and Trotski for instance were also pseudonyms. Molotov was arrested again in 1915 and this time he was banished to southern Siberia for three years but he escaped in 1916 and returned to Petrograd.

Career in the fledgling Soviet stateBeing a member of the party committee in Petrograd, Molotov played no small role in the aftermath of the Russian revolution of 1917. In these hectic times, Molotov displayed unconditional loyalty to Lenin and he never opposed changes in policy, even when he had a different opinion or when he did not understand the reasoning behind them. Later on, he would display the same blind devotion to Stalin.

In recognition of his merits and his loyalty, Molotov was quickly granted more responsibilities in the young Communist state. In 1921 he became full time member and Secretary of the Central Committee of the Party; in the same year he became candidate member of the Politburau and full time member in 1926. Molotov was no dedicated revolutionary nor a talented theoretician; his talents mainly encompassed the administrative field. He saw himself as a journalist first and foremost. In the same year, he married Polina Zhemchuzhina, a Ukranian Bolshevist and daughter of a Jewish taylor. They had one daughter, Svetlana.

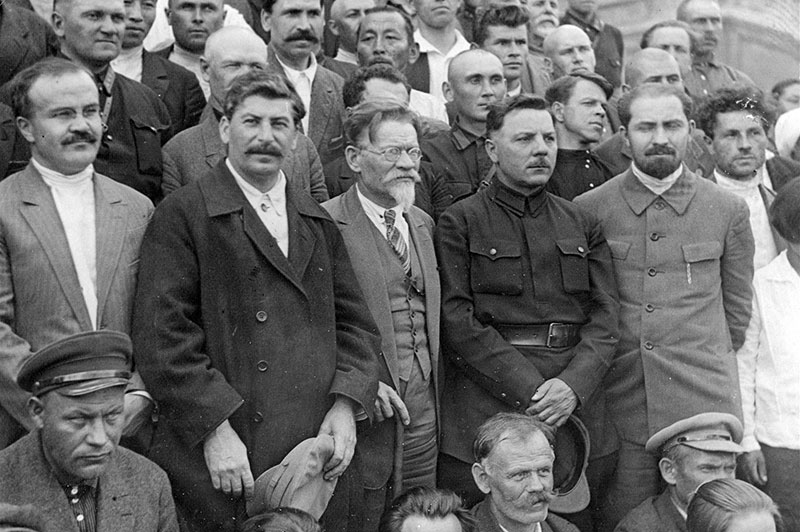

Internal AffairsAfter Lenin's demise in 1924, Molotov revealed himself as Stalin's most loyal follower, who would ultimately win the competition for power over leaders of the opposition within the Party such as Trotsky, Bukharin, Zinovyev and Kamenev. Under Stalin, Molotov co-operated dilligently in eliminating Communists who had fallen from grace. On December 19th, 1930, Molotov, aged 40, was appointed chairman of the Council of People's Commissioners, in other words, Prime Minister of the Soviet Union.

In this capacity, Molotov was the second man in the Soviet state and Stalin's most prominent spokesman. In the 30s, Molotov played a major role in internal affairs such as the Great Terror, the speedy industrialisation of the Soviet Union, the artificial famine in the Ukraine, the collectivisation of agriculture and the persecution of the Kulaks, the wealthy farmers. Molotov had been named head of the Politbureau Committee for Collectivisation; he boasted later that he had personally designated the areas from which tens of thousands Kulak families would be deported. Some three million Kulaks would not survive the harsh conditions of their deportation. Along with Stalin, Molotov was responsible for the starving of large segments of the Ukranian population in 1932 and 1933, the Holodomor; an estimated seven million civilians had starved to death in this period.

The Great Terror of the late 30s, to which millions of military, civilians, political opponents and other "enemies of the people" fell victim, consisted of large scale deportations to penal colonies but also of countless murders that had been explicitly approved by the party leaders. Most of the death sentences were signed by Stalin, Molotov, Kaganovish and Voroshilov (Bio Voroshilov). The victims were sentenced to death at break neck speed and often entirely unfounded. There were days in which Stalin and Molotov ordered more than 3.000 executions between them. "I signed most—in fact almost all—the arrest lists," Molotov later declared offhand. "We debated and made a decision. Haste ruled the day. Could one go into all the details?"

Definitielijst

- revolution

- Usually sudden and violent reversal of existing (political) the political set-up and situations.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Images

Foreign Affairs

While Stalin and Molotov conducted an extremely cruel internal policy, in the external sphere a particular peace loving policy was adopted and advances were made towards the major western powers. In the 30s, the leaders in the Kremlin found themselves threatened by an outspoken anti-Communist Nazi Germany in the west and a militaristic Japan in the east. The policy that was adopted in this period was that of a collective security in which a group of countries promises to intervene with military power in case one of the participants should be attacked. This course was embodied by Maxim M. Litvinov, since July 1939 People's Commissioner of Foreign Affairs and who was of the opinion that only collective security could guarantee peace in Europe. The major disadvantage of this system was that each member state was to be trusted to meet its obligation and that was exactly what was lacking during the interbellum. The major Western European powers, Great Britain and France saw nothing in collective security. Neville Chamberlain, the British Prime Minister rejected the idea from the beginning and believed that maintaining the dialogue with Adolf Hitler (Bio Hitler) was the only means that could offer any hope - he was of the opinion that a military partnership would put Hitler under dangerously high pressure - and the French were hesitant to conduct a foreign policy that differed much from the British.

Without British and French co-operation within a broad military partnership, no system of collective security could be developed. In the spring, negotiations between Litvinov and the British and French came to an end and on May 3rd, 1939 Litvinov was replaced by Molotov as Foreign Minister. On the one hand, Litvinov's name was too strongly connected to the failed notion of collective security; on the other hand, the Soviet Union considered an alliance with a major Europen power of crucial importance and if the British and French were not ready for this, making advances towards Germany might be a possibility. Litvinov was not the ideal person for this for he was of Jewish ancestry - his real name was Meir Wallach-Finkelstein - and the German press frequently named him Litvinov-Finkelstein. Moreover, Litvinov was married to an English woman and of rather pro-western orientation, an attitude that now had become undesirable. Molotov's appointment possibly was a signal to the Germans that the foreign policy of the Soviet Union still could turn either way.

Molotov the diplomatIt cannot be denied that Molotov owed his appointment as successor of Litvinov to his unshakeable loyalty to Stalin. In 1939 he had no experience whatsoever in the field of foreign policy. He had only been outside the Soviet Union once - to Czechoslovakia and Italy in 1922 - he spoke no foreign languages, he had never been in regular contact with foreigners and his geopolitical knowledge was extremely meager. Morerover, he had extremely strong anti-Western feelings.

In his new function, Molotov saw his main task in enlarging the territory of the Soviet Union. Territorial expansion and the spreading of Communism were, so the Bolshevists thought, part of the "'raison d'être" of the Soviet state. Many years after the war, Molotov argued that the most important result of the war had not been achieving peace; the main result was that a socialist system had been established in large parts of Central and Eastern Europe.

Immediately on taking office, Molotov was ordered to eliminate all Jewish workers from his ministry, probably to appease the Germans. In turn, Berlin did not immediately target Moscow but there surely were German officials who remarked that Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union matched well in certain ideological spheres. "Despite all differences in their respective views on the world," a German negotiator stated in July 1939, "there is one common element in the ideologies of Nazi Germany, Italy and the Soviet Union: opposition against the capitalist democracies. Neither we nor Italy has anything in common with the capitalist West. Therefore it appears rather unnatural to us that a socialist state sides with Western democracies." Despite far reaching differences, this mutual antipathy towards Great Britain and France formed a point of contact between Berlin and Moscow.

On March 31st, 1939, the day after the German occupation of Czechoslovakia, the Britsh had drawn a line by promising to come to Poland’s aid in case Germany should violate Polish independency. From mid April 1939 onwards, Hitler and his associates began considering co-operation with the Soviet Union, probably because they felt cornered. Negotiations between the Soviet Union and the British and the French continued nonetheless but the relatively low ranking Anglo-French negotiators displayed no definite drive or energy. Molotov got extremely worked up about these "crooks and liars" who "made use of all sorts of deceit and sick excuses". Molotov insisted on a military partnership but the negotiators did not wish to make any promises. The attitude of the Germans, with whom covert negotiations had been entered into, was the exact opposite. Hitler personally dispatched his Minister of Foreign Affairs, Joachim von Ribbentrop to Moscow and he made interesting economic, political and territorial proposals.

The negotiations progressed rapidly and on August 23rd , 1939, a German delegation flew to Moscow for final talks and the signing of the non-aggression pact. Stalin, Molotov, Von Ribbentrop and Ambassador Friedrich-Werner Graf von der Schulenburg discussed the last details, as well as the secret protocol, suggested by the Soviet Union and stipulating that Eastern Europe be divided between the two parties. (see Pact 23-08-1939). The pact, which has become known as the Molotov-Von Ribbentrop pact was signed in the early hours of August 24th by Molotov on behalf of the Soviet Union and by Von Ribbentrop on behalf of the Third Reich.

The pact was followed up by an extensive trade agreement. Immense amounts of grain, oil and other raw materials were transported to Germany. In exchange, the Soviet Union received valuable technology and machinery, locomotives, turbines, engines, generators, heavy weapons, various modern aircraft and military blueprints. Both parties would make good use of these commodities during the coming period, not in the least during the campaign against each other, one and a half years later. The Molotov-Von Ribbentrop pact was seen worldwide as a monster treaty, an inexplicable collaboration between two ideological enemies and a bizarre change of course by Moscow, particularly because the Soviet Union had recently conducted negotiations with the British and French. It had been a remarkable case of diplomacy by two relatively inexperienced foreign ministers.

In the course of 1940, Soviet-German relations deteriorated as a result of a dispute over issues like the Soviet attack on Finnland and the presence of German troops in Finnland and Romania. Molotov traveled to Berlin in November 1940 to discuss various issues such as joining the German-Italian-Japanese Tri Partite Pact (the Axis) but the negotiations ended without result. A few reasons were Molotov’s arrogant attitude, his lack of flexibility and his somewhat naïve notion of the German wishes.

In the spring of 1941, Molotov signed a non-aggression treaty with Yugoslavia and a neutrality pact with Japan. In accordance with the latter agreement, army units were freed that could be transferred from the Far East to the West after the German invasion. In addition, the treaty with Japan was a gesture of friendship, meant to make clear Stalin’s peaceful intentions towards the Germans. The Soviets were keen on maintaining a good relationship with Germany but the Germans had long since decided to invade the Soviet Union soon. In this period, Molotov found it hard to combine his duties as Prime Minister with his busy job as Foreign Minister and as a result he was dismissed as Prime Minister on May 6th. He was replaced by Stalin, making him vice-Prime Minister.

Definitielijst

- collaboration

- Cooperation of the people with the occupying forces, more generally spoken the term for individuals who cooperate with the occupying force is collaborator.

- Communism

- Political ideology originating from the work of Karl Marx “Das Kapital” written in 1848 as a reaction to the so-called class struggle between the proletariat (labourers) and the bourgeoisie. According to Marx the proletariat would take over power from the well-to-do classes though a revolution. The communist movement aspires an ideal situation where the means of production and the means of consumption are common property of all citizens. This should end poverty and inequality (communis = common).

- interbellum

- “Latin: Between war”. Years between the Great War and World War 2.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Kremlin

- Soviet administrative centre in Moscow.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- neutrality

- Impartiality, absence of decided views, the state of not supporting or helping either side in a conflict.

- non-aggression pact

- Agreement wherein parties pledge not to attack each other.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Images

A state of war

In the early hours of June 22nd, 1941, German troops crossed the border with the Soviet Union. The German Ambassador, Von der Schulenburg informed Molotov later that morning rather stiffly that a state of war existed between the two countries. "To what did we owe this," Molotov would have stammered. Molotov passed the message to Stalin and subsequently Molotov drafted a speech to announce the war. The text was intensively edited by Stalin but the famous, energetic final words seemed to have been drafted by Molotov: "Our case is just. The enemy will be defeated. Victory will be ours". (see Speech 22-06-1941). It was remarkable however that Molotov delivered the speeech and not Stalin. Stalin himself sought publicity as late as July 3rd, probably because he thought the details of the invasion had to be clear first before voicing his own opinion.(see Speech 03-07)

After the speech, the so-called State Defence Committee was installed, some sort of special war cabinet that would hold the highest political, economic and military power throughout the war. The idea was that the war required a maximum centralised system of government. Stalin chaired the five-man committee with Molotov being vice-chairman. In addition, Molotov became a member of Stavka, the supreme command of the armed forces, consisting of Stalin, Molotov and five army commanders.

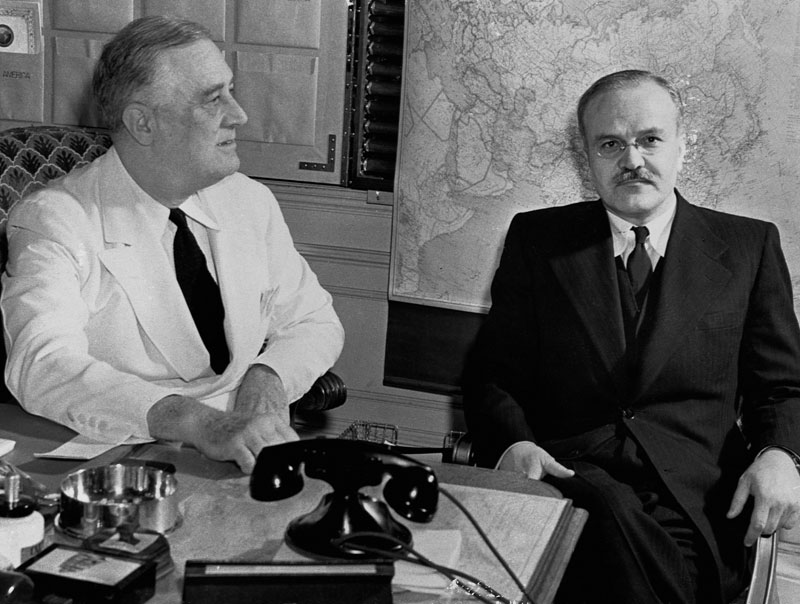

With the outbreak of war, Molotov’s main task was to enter into negotiations with Great Britain and later with the United States. The main short time goal was to enter into a partnership and to receive military support. From September 29th to October 1st, the three major powers held a conference in Moscow where it was agreed that the Soviet Union would receive arms, equipment, vehicles, trains, foodstuffs and a wide variety of other commodities under the Lend-Lease Agreement. Molotov also urged the British and Americans to open a second front in Western Europe in order to lighten the pressure on the Red Army but the Western Allies were not yet ready for such an operation. In May 1942, Molotov flew to Great Britain for talks with his equal, Anthony Eden. On May 26th, both ministers signed the Anglo-Soviet treaty with which the two countries entered into a military-political alliance. The same day, Molotov flew on to Washington where he talked to President Franklin Roosevelt (Bio Roosevelt) about further Lend-Lease deliveries and the second front.

It is remarkable that Molotov decided to appoint his predecessor, Litvinov his deputy in 1941. His connections with the west were now particularly appreciated. In 1941, Litvinov was dispatched to Washington as Soviet Ambssador but in May 1943, he was recalled to Moscow to enable him to fully concentrate on his task as Molotov’s deputy. Litvinov drafted valuable memoranda for Molotov and Stalin but at the same time, Molotov saw to it that Litvinov’s influence within the ministry remained limited.

Molotov took part in all conferences held during the war by the Big Three. In November 1943, he traveled to Iran with Stalin to take part in the Teheran Conference, the most important result being that the Western Allies would land in France in May 1944. In February 1945 Molotov and the rest of the Soviet delegation traveled by train to Yalta in the Crimea for the second major conference of the war. Since July 1944, Winston Churchill (Bio Churchill) in particular had urged to hold this Yalta conference to discuss issues like the post-war partitioning of Europe before the liberation was a fact. In July 1945, the Big Three met for the last time in Berlin at the Potsdam Conference to decide how Germany, after its recent capitulation, should be governed.

Additional tasksIn addition to his diplomatic work, Molotov was also engaged in various other projects during the war. He was actively engaged in the development of the tank industry and in 1943, he was named Hero of the Socialist Labor, the highest Soviet civil decoration for his great merits in this field. In addition, Molotov headed the nuclear program of the Soviet-Union although he was not convinced that the nuclear bomb could be deployed as a weapon. Due to the slow progress of this project, Molotov was replaced in this capacity by Lavrenty P. Beria (Bio Beria). As vice-Prime Minister, Molotov was also responsible for education and science; among other things, he solved disputes between scientists of the Moscow State University. In 1944, Molotov is said to even have contributed to the writing of the new Soviet national anthem. Having a variety of secondary tasks was not uncommon among high ranking Bolshevists: as Minister of Internal Affairs, Beria also had various side functions.

Character and working methodSubordinates considerd Molotov difficult to work with. He was unyielding, vindictive and cruel, he was obsessed by details, he frequently lost his temper in the face of other subordinates but he was extremey disciplined. Molotov lacked the knowledge and the education that were common for top diplomats but he was shaped by the cruelties of Stalinism, to which he had actively contributed but under which high ranking Bolshevists were not safe either. The result was that he stood his ground well in negotiations with world leaders and professional, experienced foreign colleagues.

Most foreign statesmen who dealt with Molotov saw him as an extremely capable diplomat. Winston Churchill called Molotov "a man of outstanding ability and cold-blooded ruthlessness, he was "robot-like" but also "an apparently reasonable and keenly polished diplomat." John Foster Dulles, the American secretary of Foreign Affairs who has had to deal with Molotov frequently since 1953, wrote: "I have seen in action all the great international statesmen of this century. I have never seen such personal diplomatic skill at so high a degree of perfection as Molotov's."

Foreign diplomats preferred to negotiate with Stalin however who was considered more lively and transparant. Milovan Djilas, a Yougoslav Communist leader who has met both Stalin and Molotov regularly, wrote that Molotov was unbending and unfathomable. "Molotov was almost always the same, with hardly a shade of variety, regardless of what or who was under consideration."

Stalin seemed to be all too happy to hide behind his foreign minister but this was just pretence: if no had to be said, this usually was done by Molotov while good news was passed by the Soviet leader himself. Moreover, Molotov’s messages to Moscow show he enjoyed more freedom of action than any other foreign minister under Stalin but it was Stalin who determined the course.

Definitielijst

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- second front

- During World War 2 the name of the front that the American and Brits would open in the West to relieve the first Russian front.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Stalinism

- Period in history of the Soviet-Union during which Stalin was the undisputed leader. The regime was totalitarian. Personality cult, terror of the secret police, cleansing, liquidations and an exaggerated chauvinism were characteristics of Stalinism. Many Eastern European countries adopted this form of dictatorship after the war.

- Stavka

- The high command of the Russian military forces in World War 2, chaired by Stalin.

Images

After the war

In the post war years, Molotov again traveled abroad many times. In 1945 for instance, he attended the Conference of San Francisco which resulted in the establishment of the United Nations and he headed the Paris peace talks of 1946-1947. Molotov attended various UN meetings in the United States where he made use of his right of veto so frequently that he was nicknamed "Mr Nyet" in diplomatic circles.

Problems on the homefrontJust like Molotov, his wife Polina Zhemchuzhina was also a top flight public official. She held top functions for years in the Department of Food Production. From 1942 onwards, Zhemchuzhina, who was fluent in Jiddish, supported the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. The purpose of this committee was to influence international opinion regarding the Soviet war effort and to solicit funds and support for the war. Stalin however fostered a deep aversion towards Zhemchuzhina. It had started years before in 1932, when Stalin’s second wife, Nadezhda Alliluyeva, committed suicide after having been humiliated by Stalin during a dinner. Zhemchuzhina had been friends with Alliluyeva and she had been the last person to see her alive.

This made her a suspect in the eyes of Stalin. Moreover, Stalin thought Zhemchuzhina exerted a negative influence on het husband and he therefore advised Molotov to divorce her but he refused. In 1939, during the Great Terror, the NKVD started investigating her for her so-called ‘contacts with spies’ but the interrogations of Zhemchuzhina’s colleagues produced such contradictory testimonials that she got away with a reprimand and a denunciation.

Towards the end of the war, Stalin began to distrust the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee; it would be a Zionist conspiracy attempting to introduce American capitalism in the Soviet Union. In December 1948, Zhemchuzhina was finally arrested for treason and sentenced to five years imprisonment in a labor camp. Molotov, still Stalin’s right hand man, was unable to effect the release of his wife, an indication that his influence was diminishing. Zhemchuzhina was released a few days after Stalin’s death in March 1953. Strangely enough, she remained kindly disposed towards Stalin. It is said her first question after her release was: "How is Stalin?" In the 60s, Stalin’s daughter Svetlana paid a visit to the Molotov family. "Your father was a genius," Zhemchuzhina had told her.

On March 4th, 1949, a few months after the arrest of his wife, Molotov was fired as Minister of Foreign Affairs because he refused to denounce her. This heralded a period in which a few other high ranking persons such as Malenkov and Beria fought their way to the top and in which Stalin unleashed a new wave of terror. During the 19th Party congress in October 1952, Stalin lashed out vehemently to some important ministers, including Molotov for not having dealt with the enemy forcefully enough during the war. Molotov fell from Stalin’s grace and his membership of the Politbureau was taken away from him.

On March 5th, 1953, the day Stalin passed away, Molotov was appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs again. He held this post for over three years but, being a fervent defender of Stalin’s controversial heritage, he collided with the new Soviet leader, Nikita C. Chrushev. His de-Stalinisation policy and his drive for peaceful co-existence with the West, went against Molotov’s grain. In June 1957, an opposition group headed by Malenkov and Molotov attempted to depose of Chrushev, mainly because they saw his denunciation of Stalin as unjust and hypocritical. The plot failed and the instigators were branded in the Soviet press.

In punishment, Molotov was appointed Ambassador to Mongolia, a post he held until 1960. In Chrushev’s vision, Molotov maintained all too friendly relations from Mongolia with the Chinese partyleader Mao Zedong, causing him to be transferred to Vienna as the Soviet representative to the International Atomic Energy Agency. However, Molotov continued criticising the party policy and in October he was recalled from Vienna and expelled from the Communist Party. Molotov retired the following year.

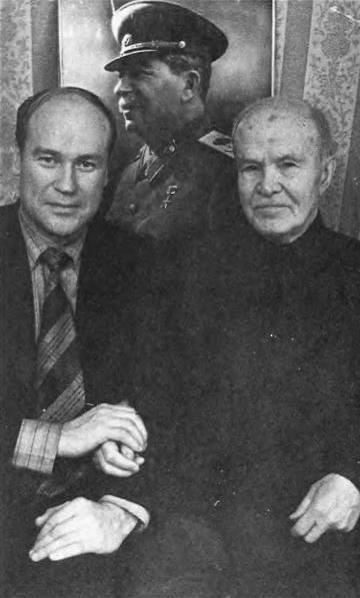

Last yearsDespite his retirement, Molotov kept very busy. He started writing his memoirs but not one magazine wanted to publish the writings of the old Stalinist. Moreover, he continued voicing criticism on Chrushev’s policy and later that of Brezhnev. Molotov frequently requested to be re-admitted to the Party but as long as he kept defending the crimes of the Stalinist regime, he could forget that. Molotov kept insisting publicly that the compulsory collectivisation and the terror had been necessary - he and Stalin had only made some "slight mistakes" and had gone a little too far. Yet, Molotov’s party membership was re-instated, after long urging, in 1984.

From 1969 onwards, the poet Felix Chuyev had a large number of conversations with Molotov. Writing memoirs was not done in Stalin’s circle of close associates - it was considered inappropiate attention for an individual within a system where everyone was equal - but Molotov accepted Chuyev’s proposal to hold a number of interviews. Molotov’s feeling that Chrushev and later Soviet leaders had betrayed the revolution was strong and he wanted to explain the reasons for the Stalin regime to the general public. Chuyev on his part recognised that those interviews could form a valuable portrait of an era: after all, Molotov was the only person to have shaken hands with Lenin, Stalin, Churchill, Roosevelt, Hitler, Hess (Bio Hess), Göring (Bio Göring) and Himmler (Bio Himmler). The compilation of the 140 interviews, in which Molotov is amazingly outspoken about his considerable role in the Great Terror for instance, was published in large numbers in 1991.

In his final days, Molotov was one of the last of the living Bolshevists of the old guard. He remained proud of Stalin and his heritage until the end. He also continued denying vehemently that the Molotov-Von Ribbentrop pact signed by him, had included a secret clause that had divided Eastern Europe between Germany and the Soviet Union.

In June 1986, Molotov was admitted to a hospital in Moscow, suffering from pulmonary inflammation, where he passed away on November 8th , 1986. He had suffered seven strokes in his life time and yet had reached the age of 96. Molotov was buried in the prominent Novodeviche cemetery in Moscow.

Molotov was highly decorated during his career. He was namend Hero of Socialist Labor and was awarded the Order of Lenin four times. A light cruiser and various towns and districts have carried his name for a while. Best known of these is the Russian city of Perm and the province with the same name which were renamed Molotov in March 1940 in his honor and on the occasion of his 50th birthday. The name Perm returned again in 1957.

Definitielijst

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- revolution

- Usually sudden and violent reversal of existing (political) the political set-up and situations.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Images

Information

- Article by:

- Auke de Vlieger

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

- 06-'42: Our Diary of the War

- 08-'45: Russia Smashes In to End the War With Japan

The War Illustrated

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- MAWDSLEY, E., Thunder in the East, Hodder Education, Londen, 2005.

- MONTEFIORE, S.S., Stalin, Orion Books Ltd., Londen, 2004.

- OVERY, R., Russia's War, Penguin Books, Londen, 1999.

- PLOKHY, S.M., Yalta, Viking, New York, 2010.

- RESIS, A. (RED.), Molotov Remembers, Ivan R. Dee, Chicago, 1993.

- ROBERTS, G., Molotov, Potomac Books, Dulles, 2012.

- ROBERTS, G., Stalin's Wars, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2006.