Previous history

Introduction

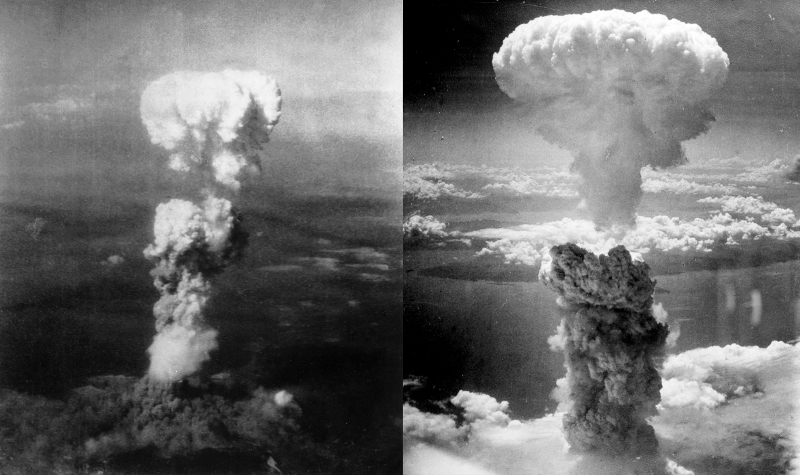

"I am aware of the tragic impact of the atomic bomb. It is a terrible responsibility which has come to us. We thank God it has come to us instead of to our enemies and we pray He may guide us in using it in His footsteps and to His purposes." Harry S. Truman, August 9th, 1945.Monday, August 6th, 1945 began as a beautiful and sunny day in Hiroshima. The city had fared rather well up to then. Just like in the rest of Japan, the city suffered from shortages of raw materials and food stuffs but generally speaking, the citizens were rather content. Up to that moment, Hiroshima had been spared the massive American air raids other cities in Japan suffered so much from but all that was soon to change.

Nuclear fission

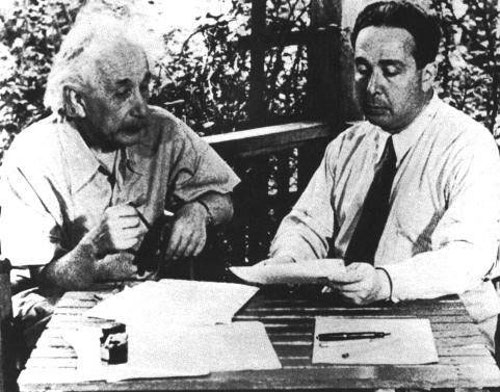

On July 17th, 1939, three Hungarian scientists, Leo Szilárd, Eugene Wigner and Edward Teller paid a visit to Albert Einstein in his summer residence at Peconic Bay on Long Island. The gentlemen talked for a few hours. In August, Szilárd and Teller would be visiting Einstein once more. The conversation was held in German mostly as Einstein was not very fluent in English yet. The Hungarian scientists and Einstein discussed a matter that takes us back to 1932.In 1932, British physicist Sir James Chadwick had discovered the neutron, a particle without charge, only mass, in the nucleus of an atom. During the following years, a number of physicists conducted experiments, firing neutrons at the nucleus of an atom. In a similar experiment in December 1938 in Berlin, conducted by German scientists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassman, the new element barium (Ba) was formed of about half the mass of a uranium atom. Two other German scientists, Lise Meitner and her nephew Otto Frisch therefore drew the conclusion that the atom had been split. Meitner, a Jewess originally from Austria, had escaped to Sweden via the Netherlands in 1938. Frisch passed Meitner’s idea to Danish scientist Niels Bohr. He investigated the idea further.

Bohr discovered, among other things, that a uranium isotope (U-235) would be easier to split than the natural version of uranium (U-238). U-235 however was and is very rare: a mere 0.7% of the mined uranium is U-235. Isotopes are atoms occupying the same position in the table of chemical elements as the element they belong to but with a different mass. This means that the isotopes of an atom contain the same number of protons (particles with a positive charge, as opposed to electrons which have a negative charge) but a different number of neutrons. Bohr discussed the findings of Meitner and Frisch during a scientific conference which was held in America on January 26th, 1939. In this way, Szilárd and his fellow physicists came to know about the idea of nuclear fission and its consequences.

Each physicist immediately appreciated the possibilities of nuclear fission. During fission, two atoms are formed with a positive charge repelling each other. Moreover, during fission a small amount of mass is "lost". This mass is being transformed into energy, according to the well known formula, discovered by Einstein: E=mc2, which would mean an extremely powerful explosion. As more neutrons are set free during fission than are being used for the fission, a chain reaction will be triggered freeing more neutrons splitting more atoms and so on. If one could succeed in starting such a chain reaction, it would be possible to produce a bomb with a terrible explosive power.

The three Hungarian scientists had drafted a letter they wanted to hand over to the President of the U.S. Franklin Roosevelt (Bio Roosevelt). In it, they pointed to recent developments that would enable the production of a nuclear bomb, at least in theory, and they warned of the danger of Nazi Germany developing such a weapon. At the time, this fear was certainly not unfounded. During the interbellum, Germany was the pioneer in the scientific field and did have the required raw material at its disposal: the uranium mines in recently annexed Czechoslovakia. In their opinion, the president of the U.S. should finance research into the development of a nuclear bomb so the country could stay ahead of the Germans in the construction thereof. They asked Einstein and a number of other prominent scientists to co sign this letter, which they did. On October 11th, 1939, banker Alexander Sachs handed the letter to Roosevelt. His exact reaction is unknown. After having read the letter, the president did remark something like "so we’ll have to somehow prevent them from blowing us up."

Further research

On October 21st, 1939, a committee was formed in the U.S.: the Advisory Committee on Uranium, chaired by scientist Lymann Briggs. After just one month, an advice was presented to Roosevelt, urging for more research. Unfortunately, only a small amount of money was made available for this, some $ 6,000 which was spent on a number of experiments by Fermi and Szilárd at Columbia University. After this, research in America petered out somewhat. The U.S. were not yet involved in the war and recognition of its importance did not penetrate yet.In particular the British insisted on more action by the Americans. Two physicists at Birmingham University, Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls published a memorandum in March 1940 indicating that a relatively small amount of uranium was required to produce a bomb. Initially, for instance in Szilárd’s letter, a critical mass of a few tons was reckoned with. Frisch and Peierls came to the conclusion that a few pounds would be sufficient to trigger a chain reaction. Consequently, the British formed MAUD (Military Application of Uranium Detonation) of which all important British physicists were members. Research was done into the enriching of uranium and other technical problems inherent to the construction of an atom bomb. Enriching of uranium was possible, according to research by Franz Simon.

In March 1941, MAUD published a report, stating that for a U-235 bomb, a critical mass of some 26 lbs was sufficient and that such a bomb would have an explosive power of 18 kilotons. The report was sent to the U.S. and ended up, unread, in a drawer of Briggs’ desk. Only after a journey to the U.S. in August by British physicist and MAUD member Marcus Oliphant, the matter swung into high gear. Oliphant discussed the matter with a number of American physicists including James Conant and Ernest Lawrence. Again, a number of investigative committees were founded in the U.S. In October 1941, science advisor Vannevar Bush submitted the MAUD report to the president. Subsequently, Roosevelt ordered the National Academy of Sciences to conduct research into the bomb project. The investigation gained more priority after the attack by Japan on Pearl Harbor, December 7th, 1941 and the subsequent declaration of war against the United States by Germany on December 11th. In December, Bush set up the Office of Scientific Research and Development in order to coordinate the various research projects and to start new and more intensive research.

Definitielijst

- Hiroshima

- City in Japan where the first operational atomic bomb was used on 6 August 1945.

- interbellum

- “Latin: Between war”. Years between the Great War and World War 2.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

Images

Development of the atom bomb

The Manhattan project

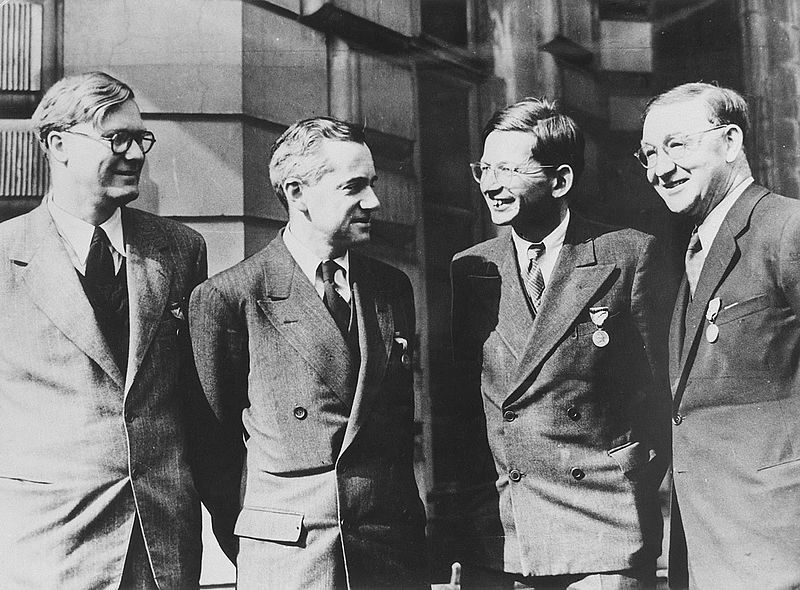

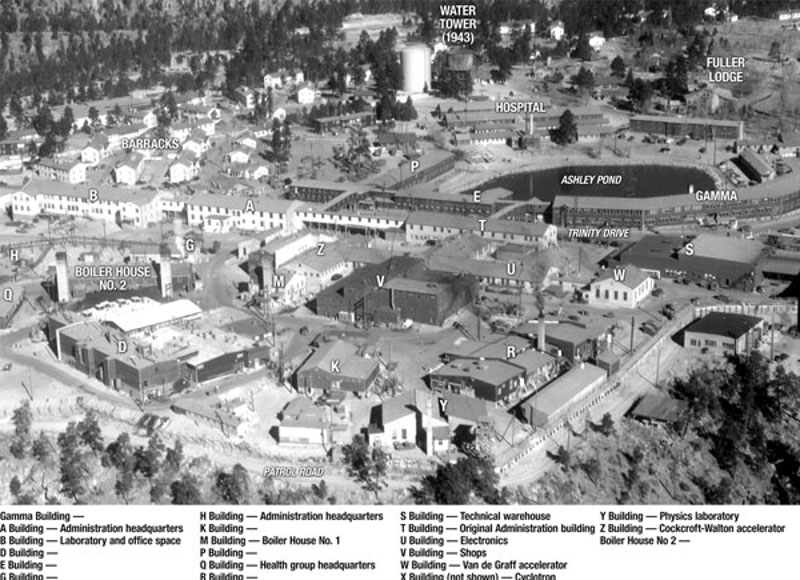

On January 19th, 1942, Roosevelt gave the green light for a project to develop an atomic weapon. The United States Army Corps of Engineers with its headquarters in Manhattan District, New York was in charge of it. Research was conducted into possibilities and costs inherent to the production and development of an nuclear weapon. In June 1942, this led to the start of the Manhattan Project and this name became official on August 13th of the same year.On September 17th, 1942, Leslie R. Groves, recently promoted to Brigadier-general, was placed in charge. Groves was an intelligent and respected officer who recently had made a name for himself with the construction of the Pentagon, the headquarters of the American armed forces in Washington. He was praised for his unbridled energy and his great gift for organization. The newly appointed chief immediately went ahead energetically. He managed to raise the priority of the project in order to make more funds and material available. Groves appointed brilliant physicist Robert Oppenheimer chief of the laboratory (henceforth designated Project Y) where the bomb would eventually be developed and produced.

On September 24th, 1942, by order of Groves, 8.8 square miles of land in Oak Ridge, Tennessee was purchased. Here, two plants for the enrichment of uranium were built. This area (henceforth designated site X) was selected because the many flood-control dams would provide the required electricity. Two methods were in use simultaneously as it was unknown which was best. In both, U-238 was transformed into a gas, uranium hexa-fluoride (UF6). In the gas diffusion process, the gas passed through a porous membrane with holes of 0.0000394 inch. The U-235 particles were slightly lighter so they could pass through the membrane while the heavier U-238 did not. In the electromagnetic process, the gas passed through a curved vacuum tank with a strong magnetic field. The lighter U-235 particles were diverted a little less and could be separated. The construction of the facilities required for the production took much time and money. Moreover, both methods had to be repeated frequently to produce a pure form of U 235. In 1942, a work force of 3,000 was employed in Oak Ridge; in 1945 this number had increased to 75,000.

In Hanford, in the state of Washington, usually designated as Site W, the nuclear reactors were built to produce plutonium. Early 1941 a team of scientists at Berkeley University, California, headed by Glenn T. Seaborg, had discovered that when uranium is bombarded with deuterium a new element is formed after a series of mutations, plutonium 239. Plutonium turned out to be even easier to split than uranium 235. In reality, only a small amount of the uranium was transformed. The plutonium had to be separated from the remaining uranium first. Hanford was considered the ideal site. Due to its distant location, it could easily be sealed off and the Columbia river provided the necessary cooling agent for the reactors. The reactors were fired up towards the end of September 1944 and on February 5th, 1945, the first 2.8 ounces of plutonium were delivered.

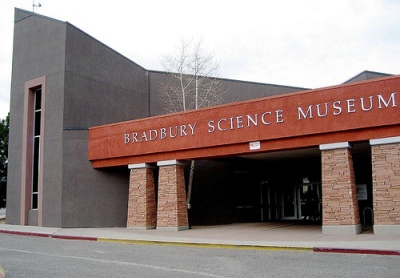

Los Alamos

Groves and Oppenheimer selected Los Alamos as the site for the location of the laboratory where the bomb was to be developed and constructed. This village in desolate and thinly populated New Mexico was best suited for conducting the secret project, more so because it could be well guarded and sealed off. December 2nd, 1942, the land and the existing boarding school for boys were purchased by the government. Los Alamos, 7,546 feet above sea level, expanded to a complex eventually employing 4,000 workers. Including the scientists’ partners, a total of 6,000 people resided in Los Alamos. The project was under the highest degree of secrecy. All mail addressed to the inhabitants of Los Alamos was to be sent to: c/o Military Agency, Office of U.S. Engineers, Box 1539, Santa Fe, New Mexico. This address was also entered on the drivers license of the employees and as place of birth of the children born here. All outgoing mail was censored and phones were tapped.Almost all well known physicists of their time were employed at Los Alamos, including the Americans David Bohme, Norris Bradbury, Richard Feynman, John Manley and Robert Oppenheim ere; the Dane Niles Bohr and Italian Enrick Fermi. The Manhattan Project eventually evolved into one of the largest operations of World War Two. A total of 130.000 persons would be employed in the various locations. The cost would ultimately exceed two billion dollars.

On December 2nd, 1942, at the Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago, Enrico Fermi succeeded in starting the first chain reaction. This was a giant step forward. This was by the way not the very first nuclear reactor. In June 1942, German scientists had succeeded in propagating electrons. But their experiment was not continued after an accident. In March 1944, the first ounces of enriched uranium, produced by the electromagnetic method, were delivered to Los Alamos. The facility for the gas diffusion became operational in February 1945. In July 1945, 22.5 lbs of enriched uranium was delivered to Los Alamos, 85% of this consisted of U-235. The required amount of uranium 238 for this project mainly came from a uranium mine of the Union Minière du Haut Katanga in Belgian Congo. After the Germans had occupied Belgium in 1940, the manager, Edgar Sengier had shipped the uranium to the U.S. as a precaution. No less than 540,000 lbs of this ore was openly stored in a warehouse on Staten Island. Another part came from a mine in Colorado.

Definitielijst

- Manhattan Project

- The American development of the Atomic bomb during World War Two.

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

Images

Delivering the bomb

Project Alberta

In March 1944, Leslie Groves had his first meeting with General Henri (Hap) Arnold, Commander-in-Chief of the U.S.A.A.F. in order to discuss how the atomic bomb could be dropped. At that moment in time, there was only one aircraft available, capable of carrying the atomic bomb with an estimated weight of 11,000 lbs, the British AVRO Lancaster. Using a British airplane could cause problems though as the Americans had little experience with the maintenance and technique of the Lancaster. Hope was therefore placed on the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, still under development. Nationalistic feelings certainly played a role in this decision. Major-general Oliver Echols was appointed liaison between the U.S.A.A.F. and the Manhattan Project. In fact, his deputy Colonel Roscoe Wilson was charged with this task. Within the Manhattan Project, a separate unit commanded by Captain William Parsons was founded, charged with finding the best way how to prepare the bombs in advance and how to drop them from an aircraft. The code name for this project was Alberta.On August 29th, 1944, Paul Tibbbets was selected as the pilot for the mission to drop the first atomic bomb. His commanding officer, Uzal Ent and three representatives of the Manhattan project – Lieutenant-colonel John Lansdale, Captain William Parsons and Norman Ramsey – briefed Tibbets about the mission at 2nd Air Force headquarters at Colorado Springs Army Air Field. Later, Tibbets declared: "They told me I was going to destroy a city with a single bomb. That sure came as a surprise." At that moment, Tibbets was already a well known pilot. He had piloted the leading B-17 on U.S. 8th Air Force’s first mission from England to Rouen in France on August 17th, 1942. He had also been involved in testing the B-29. He had 41 operational missions under his belt. At the end of the meeting, commander Ent stated: "Colonel, if everything goes well, you’ll be a hero but if it fails, you’ll be the greatest scapegoat of all time."

Tibbets was transferred to 393rd Bomb Squadron on Wendover Field, Utah. The operation was given the official code name Silverplate, also entailing training and conversion of the aircraft to prepare them for use of nuclear weapons. The latest version of the B-29 bomber was chosen for the attack. All armor plating and almost all of the defensive armament was removed, except the tail turret. This added 4,200 ft to the operational ceiling of the aircraft and speed and maneuverability also increased. From October 1944 onwards, the unit practiced intensively in dropping the atomic bomb. This entailed dropping a test bomb, in length and weight equal to the real thing, from an altitude of 29,500 ft within a circle 750 ft in diameter. This circle was shrunk to 328 ft in stages. The bomb had to be aimed visually; radar could not be used as it might interfere with the mechanism inside the bomb. Radar images would also increase the risk of misidentification of the target. During these exercises, experiments were also conducted with the remotely controlled detonator of the bomb. As soon as the bomb had been dropped, the aircraft had to leave the target area fast. It was assumed that the shock waves of the explosion could probably destroy the aircraft. The attack with the nuclear device would be carried out by a single bomber without any escort. The assumption was that the Japanese would pay no attention to a solitary aircraft.

All crewmembers involved were thoroughly screened by the intelligence department of the Manhattan Project. They were subjected to very severe security measures. Outside the base, the men were forbidden to say anything about their work. If they did, they were transferred to another unit immediately. The men were competent but discipline was sometimes poor. For instance they frequently misbehaved in their spare time.

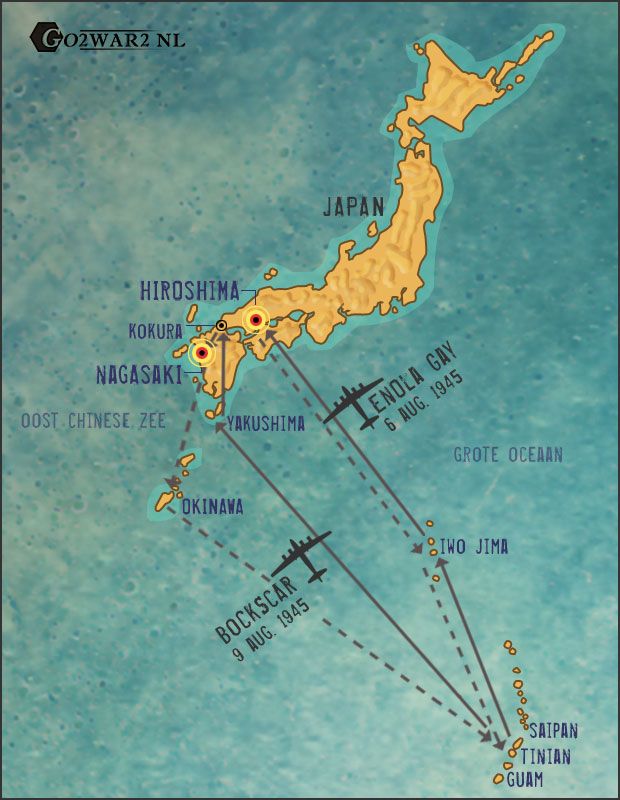

The 509th Composite Group

On December 17th, 1944, a new Bomb Group was founded, the 509th Composite Group, commanded by Lieutenant-colonel Paul W. Tibbets (he was to be promoted to Colonel in January 1945). The new unit comprised the 393rd Bombardment Squadron and the 320th Troop Carrier Squadron equipped with the C-47 Skytrain (Douglas DC 3) and the C-54 Skymaster (Douglas DC 4). In December 1944, 10 aircraft with 15 crews were temporarily transferred to Batista Field in Antonio de los Baïos on the island of Cuba in order to practice long distance navigation over the ocean. On March 6th, 1945, one more unit was added to the 509th, the 1st Ordnance Squadron Special (Aviation). This unit consisted of experienced technical personnel to supervise the technical equipment of the aircraft and the transport of the atomic bombs. The 509th now consisted of 1,767 persons (225 officers and 1,542 rank and file). In April 1945 they were re-equipped with the new Silverplate B-29s. These were equipped with improved fuel injected engines, electrically adjustable propellers and improved bomb doors.In December 1944, it was decided the attacks should be launched from the Marianas islands. In February 1945, Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz was informed about the (objective of the) Manhattan Project. Being Commander-in-Chief Pacific, the attacks would be launched in his theatre of operation. Initially, the missions would be flown from the island of Guam but some time later the island of Tinian was chosen as it had a better air field and lay 125 miles further to the north and so closer to Japan.

During April and May 1945, the 509th Composite Group was transferred to North Field on the island of Tinian. The unit was incorporated in the 313th Bombardment Wing. Security was tight. The crews were housed in a separate section of the base. Contact with other military personnel was restricted as much as possible. Apart from making some test flights, there was little to do for the unit in the next few weeks. Internal arguments erupted and discipline dropped somewhat. The crews of other units envied the men of the 509th as they did not have to fly any combat missions and were leading a comfortable and safe life. A somewhat cynical song arose, the first verse reads as follows:

- "Nobody knows

Into the air the secret rose

Where they’re going, nobody knows

Tomorrow they’ll return again

But we’ll never know where they’ve been.

Don’t ask us about results or such

Unless you want to get in Dutch.

But take it from one who is sure of the score,

The 509th is winning the war."

From July 1945 onwards, the 509th flew a total of 12 combat missions in order to experiment with the technique of dropping an atomic bomb. This meant one B-29 dropped a Pumpkin bomb on a Japanese city. A Pumpkin was a heavy 11,700 lbs incendiary bomb that strongly resembled the plutonium bomb, outwardly and ballistically, that would ultimately be dropped over Nagasaki. Apart from the nuclear charge, they were almost identical. During missions on July 20th, 23rd, 26th, 29th and August 8th and 14th, various bombers would drop a total of 49 of these devices.

Definitielijst

- Manhattan Project

- The American development of the Atomic bomb during World War Two.

- Nagasaki

- Japanese city on which the United States dropped the second atomic bomb on 9 August 1945.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Images

Targets

Japan on the defensive

In August 1944, the Americans captured the Marianas, a group of 15 islands, among them Guam, Tinian and Saipan. The Japanese main islands were now within range of the American Bomb Groups in the Pacific that were recently equipped with the B-29. The first attacks did not have the desired effect yet but when the new Commander-in-Chief, Major-general Curtiss E. Lemay proposed switching to strikes with incendiaries at relatively low altitude, they managed to inflict severe losses among the population and on the industry.Japan gradually lost more territory in the Pacific. In 1945, the Philippines were captured by the Americans. In February they lost the battle for Iwo Jima and in April, the Americans invaded Okinawa, some 347 miles from the Japanese home islands. In October 1944, they had switched to a new method of attack. Pilots let their aircraft, loaded with explosives, crash dive onto an American naval vessel in order to damage or sink it. The Americans were shocked by these suicide attacks, known as Kamikaze. It became obvious that the Japanese would keep resisting until the bitter end and that no means would be left untried.

On April 12th, 1945, President Franklin D. Roosevelt passed away unexpectedly. His vice-President, Harry S. Truman, succeeded him. At that moment, Truman did not known anything about the existence of the Manhattan Project. On April 25th, he was informed about it by his Secretary of War, Henry Stimson.

Nazi Germany surrendered on May 8th, 1945. The war in Europe was over now. At that moment it finally became clear that not much had come from the German plans to develop an atomic bomb. As early as 1942, Albert Speer had already ordered to slow down its development when it dawned on him that the project would take a long time and that Germany probably would not succeed in developing an atomic bomb before the end of the war.

Selecting the targets

Early 1945, when it became clear that the atomic bomb was almost completed, research was started into the best way to deploy it. There was no doubt whatsoever about the bomb being deployed at all. There was a war on and the United States had the means at her disposal to end it quickly. In April 1945, a commission was formed, chaired by Secretary of War Henry Stimson, recommending to deploy the bomb against a target in Japan without previous warning.Some scientists involved in the Manhattan Project proposed to drop a bomb, after a preceding notification, on an uninhabited area in the Pacific. Their underlying thought was that when the Japanese would observe what kind of dreadful weapon the Americans had at their disposal, they would agree to unconditional surrender. This idea was rejected. First, the fact that the bomb would not function was taken into consideration as a failure during a test explosion would not make the slightest impression on the Japanese. It was also feared that when the forewarned Japanese were to know where the explosion would take place, they might well move Allied prisoners of war into the area. Moreover, as a result of that kind of action, the element of surprise by the new weapon would be lost and doubt prevailed whether the deterring effect of such a test explosion would be strong enough. In a meeting with a number of high ranking military, including Groves, on June 1st, 1945, Stimson declared: "If we really expect the surrender of the Emperor and his advisors, we must deliver a severe blow to them, which will be convincing evidence of our capability to destroy the Empire with one stroke. A severe blow like that would save the lives of more Americans and Japanese than it would cost."

In April 1945. General George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff of the American armed forces, ordered Groves to select a number of possible targets for the atomic bomb. Subsequently, Groves formed a committee, chaired by himself. Following the advice of this committee, a Japanese military installation was sought, surrounded by houses and other buildings that could easily be destroyed. The town had to be large enough so the damage inflicted would be limited to the town itself in order to provide a good idea of the destructive power of the bomb.

During a meeting on May 28th, 1945, four cities in Japan were selected as targets: Kyoto, Hiroshima (an industrial center with a large harbor), Niigata (a port with steel and aluminum plants), Yokohma (a center of aviation industry and machinery) and Kokura (a center of the ammunition industry). Bombing these cities with conventional ordinance was prohibited until further notice. Leslie Groves initially opted for Kyoto because of the local intelligentsia which would be quite able to appreciate the power of the atomic bomb. Attacking Kyoto however met resistance from the Secretary of War, Henry Stimson. He argued Kyoto was of great religious importance to the Japanese and the city also possessed an impressive historical center, something Stimson had witnessed himself during his honeymoon. Therefore he pleaded to spare the city. Marshall shared his view and Kyoto was taken off the list.

Hiroshima

Next target on the list was Hiroshima. In August 1945, Hiroshima counted approximately 255,000 inhabitants. The city was built on six islands and surrounded by hills on three sides. 90% of the closely packed houses were constructed of wood. Hiroshima had a large harbor and well developed industry. It was a important center of ship building and aircraft production. The Mitsubishi company had a number of plants in the city. Also located in Hiroshima was the Toyota factory which churned out 6,000 rifles a week. The city also served as an important supply and communication center for the Japanese army and navy.The defense of Hiroshima consisted of 21 anti aircraft guns of various caliber, usually 2.8 or 3.1 inch. The city was poorly prepared for an air raid. The number of air raid shelters was insufficient. The fire brigade was poorly trained and there was too little pressure on the fire hydrants. From 1944 onwards, digging of fire trenches was begun for which hundreds of houses had to be torn down. Until August 1945, the city had been attacked only sporadically. On March 19th, 1945, four American fighter bombers dropped two bombs on the city, killing two people. On April 30th, a B-29 which had strayed from its formation, dropped nine bombs on the city, killing 10 persons. In the city a persistent rumor prevailed to the effect that it was being spared American air raids as Japanese living in the United Stated had been urging for this or because the Americans wanted to use it after the war as headquarters of the forces of occupation. Another rumor was that the city was being spared because the Americans had something special up their sleeves.

In June 1945, the Japanese garrison in the city was expanded in order to counter the expected Allied invasion on the home island of Honshu. Headquarters of the 2nd Army Corps, commanded by Field marshal Shunroku Hatta was set up in the castle of the city. In August, 40,000 soldiers and 5,000 marines were billeted in Hiroshima. The headquarters of the 59th Army and the 5th and 224th Division were also moved to the city. Initial steps were taken to establish a civilian militia. In this connection, women and the elderly were trained in using bamboo spears in combat. In order to repel the expected invasion, numerous small vessels made mostly of plywood and equipped with an explosive charge on the bows. were berthed in Hiroshima harbor. In case of a possible invasion, these vessels were to ram enemy ships.

Nagasaki

On July 22nd, Arnold had a meeting with Henri Stimson. Arnold suggested selecting Nagasaki instead of Kyoto as a possible target for the atomic bomb. The was the first time Nagasaki was mentioned. On July 30th, the city was added to the list of possible targets. Just like Hiroshima, the city had lots of industry and a large harbor. Mitsubishi had a number of plants in the city, producing goods such as weapons, ammunition, electrical equipment, torpedoes and steel. The company also owned a shipyard here. In August 1945, the city counted some 260,000 inhabitants. Just like in other Japanese towns, buildings consisted mostly of wood and paper. The Americans were aware a prisoner of war camp was located in the city. It was discussed therefore whether bombing of Nagasaki should be abstained from. Eventually, Stimson decided not to but the city was placed low down on the list.The PoW camp in Nagasaki, Fukuoka 14B, was some 820 yards from the central railway station near the river Urakami. The camp had been established in April 1943 to house 300 Dutch soldiers from the Dutch East Indies. Shortly after arrival, seven inmates had already died from dysentery, due to the bad hygienic situation during their transport. Living conditions in the camp itself were not so good. Feeding and housing were poor and the inmates were frequently tortured by their guards. Life in the camp however was not so harsh as the regime the inmates had been subjected to during their work on Birma-Siam railway line. During the cold winter of 1943-1944 dozens of Dutch died from pneumonia. The men were forced to work at the Mitsubishi shipyard, some 2 miles from the camp.

In June 1944, Fukuoka was expanded in order to house more inmates. Later on, a number of them was put on transport again. In the spring of 1945, work on the shipyard was suspended, owing to a lack of raw materials. The men were now employed in munitions and engine plants. On June 30th, 1945, the population of the camp consisted of 201 inmates, 153 Dutch, 19 British and 29 Australians.

Despite the official ban on conventional bombing, Nagasaki was attacked several times in July by the U.S.A.A.F. The heaviest attack was launched on August 1st, 1945 and caused considerable damage. Nothing is known about possible victims.

Definitielijst

- brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- caliber

- The inner diameter of the barrel of a gun, measured at the muzzle. The length of the barrel is often indicated by the number of calibers. This means the barrel of the 15/24 cannon is 24 by 15 cm long.

- Hiroshima

- City in Japan where the first operational atomic bomb was used on 6 August 1945.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Kamikaze

- “Divine Wind”. A kamikaze pilot would fly himself, his airplane and bomb(s) literally into an enemy target, preferably a US ships. This was a noble cause, considered a most honourable death for the emperor. Several thousands of kamikaze pilots died this way.

- Manhattan Project

- The American development of the Atomic bomb during World War Two.

- marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- Nagasaki

- Japanese city on which the United States dropped the second atomic bomb on 9 August 1945.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- PoW

- Prisoner of War.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Siam

- Name of Thailand

Images

Dress rehearsal

Test explosion

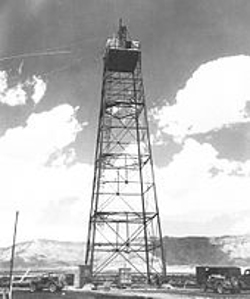

Prior to the actual deployment of the bomb, a test explosion was conducted. In late 1943, preparations for this were already on the way. In November 1944, construction of the base camp in Alamogordo was begun with. According to some sources, Harry Truman had decided as early as June 18th, 1945 that when the test was successful, the next two atomic bombs that came available would be dropped on Japan. It was decided to use the plutonium bomb. The detonator of the uranium bomb was considered so dependable, there was no need to test it. Another reason for this decision was the limited stock of fissionable uranium. On July 16th, 1945, the test explosion, code named Trinity, took place in Alamogordo, 185.6 miles south of Los Alamos. Welding goggles were distributed in advance to protect the eyes from the hazardous flash of light from the explosion. It is said that some persons had even applied sun cream. The scientists were not sure what to expect. No one knew exactly how far the chain reaction would go, it could even extend outside the target area. The radio active fall out could well be deadly.In the night of June 15th to 16th, the plutonium bomb nicknamed the Gadget was hoisted onto the top of a tower, 115 feet high at some 9.3 miles from base camp. It was chosen to have the explosion several hundreds of feet above the ground to simulate the effect of a bomb dropped from an airplane. Due to bad weather, the test was postponed and it was even considered cancelling it altogether as rain could cause shorting of electrical circuits inside the bomb. The weather conditions could also result in more radiation and fall out, radio active deposit resulting from a nuclear explosion. During the night however, the weather cleared and the rain stopped. The actual explosion took place at 05:29:45 hours. Mankind entered the nuclear era with a massive flash of light. Brigadier-general Thomas Farrell, Groves’ deputy, described the explosion as follows: "The effects can be called unknown, magnificent, overwhelming and terrifying. The landscape was lit up by a scorching light with a brightness many times larger than that of the sun. It was golden, purple, gray and blue. It lit up every summit, every ridge and valley of the nearest mountains with a clarity and beauty impossible to describe and you should have seen it with your own eyes to imagine it."

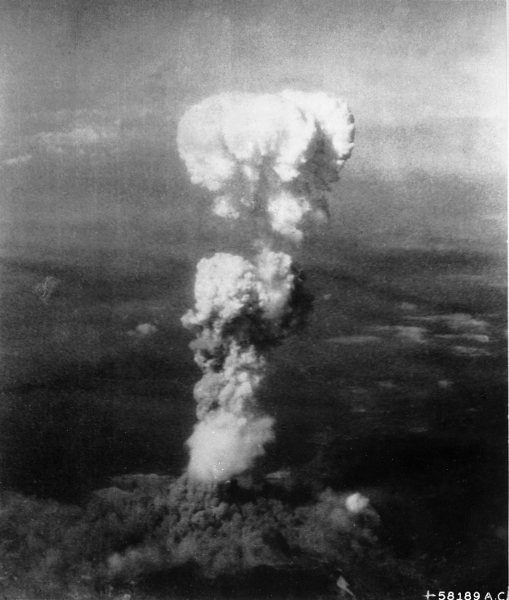

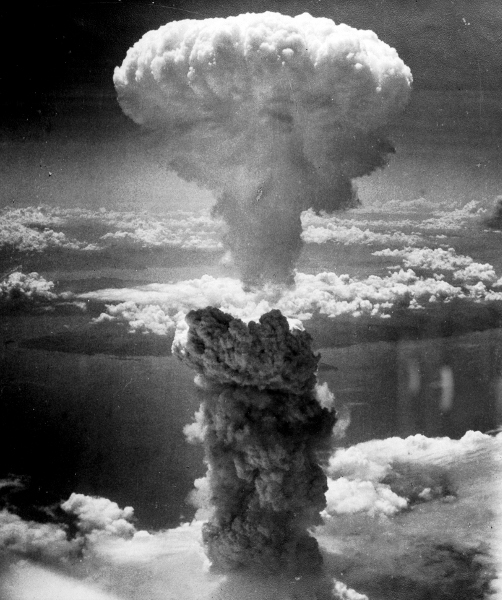

A mushroom cloud rose to an altitude of 39,700 feet. 40 seconds later, the deafening explosion and the shock wave followed. Estimates of the strength of the explosion varied between 18.6 to 21 kiloton, four times the strength the scientists had reckoned with. The temperature in the center of the explosion rose to 100 million degrees Celsius. Within a radius of 5,250 feet all animal life had disappeared. The tower carrying the bomb had literally vanished into thin air. Because the explosion had taken place at a height of 115 feet, the crater that was created as a result was relatively small. This was 5 feet deep and had a diameter of 29,9 feet. All sand in a radius of 2,400 feet had melted. At a distance of 1.8 miles, a soldier was blown off his feet by the shock wave which was still noticeable at a distance of 100 miles. After the successful explosion, Groves remarked: "The war is over. One or two of these things and Japan is finished.". Many stories have popped up after the war about Robert Oppenheimer’s words, for instance he would have quoted a verse from the Bhagavad (an ancient Hindu spiritual poem). According to his brother Frank, standing next to him, his statement was a bit simpler: "It worked."

In order to explain the light flash and the explosion, a message was released stating that a munitions shed containing gas grenades and pyrotechnical material had exploded on Alamogordo Air Force Base. News of the successful explosion was passed on to Harry Truman who was in Germany at the time to attend the Potsdam conference. The message read:

- Top Secret

Department of War

Section Confidential Messages

Secretary General Staff

Col. Pascoe, July 16th, 1945

Urgent

War 32887

To Hummelsine, for Colonel Kyle exclusively from Harrison to Stimson

Operation performed successfully this morning. Diagnose not yet complete but results seem satisfactory and already exceed expectations. Message to local press required as strong interest rising in a wide area. Doctor Groves satisfied. Returns tomorrow. Will keep you posted. End 161524

Potsdam replied with the following message:

- Top Secret

From: Endstation

To: Department of War

To: Secretariat General Staff, exclusively for Mr. George L. Harrison from Stimson

Top Secret S.V.C. 384:

My heart felt congratulations to doctor and consulting physician.

At this conference, Joseph V. Stalin (Bio Stalin) was informed about the existence of the Manhattan Project also. Stalin however had been informed a long time ago though as spies within the project had forwarded everything to the Russian secret service. When Truman informed Stalin about the existence of the bomb, he allegedly remarked coolly: "Well, I hope you’ll have something against the Japanese." The Potsdam Conference ended with a communiqué dated January 26th, 1945, in which the leaders of the United States, Great Britain and the Republic of China indicated that only unconditional surrender by Japan would be acceptable and that refusal of this offer would lead to utter and fast destruction. The Japanese did not accept the offer and decided to sweep it under the rug (mokasatsu in Japanese). On July 21st, Truman had already made the irrevocable decision to deploy the atomic bomb against Japan.

On July 25th, Thomas Handy, General George Marshall’s deputy who was in Berlin at that moment, issued an order, drafted by him, to General Carl Spaatz. The order for this had been given on July 24th by Henri Stimson. This order marked the following cities as possible remaining targets: Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata and Nagasaki. The attack was to be launched after August 3rd, weather permitting. On July 25th Truman wrote about the atomic bomb in his diary: "It seems like this is the most terrifying thing ever discovered but it can also become the most effective."

Little Boy and Fat Man

Most parts of the uranium bomb, including the firing device, were transferred to Tinian aboard the heavy cruiser U.S.S. Indianapolis. When the cruiser left San Francisco on July 16th, she was carrying all uranium available to the United States at that time. The cruiser arrived in Tinian on July 26th and four days later on her return journey, she was torpedoed and sunk. A number of other parts were transported by a C-54 of 320 Squadron. Members of Project Alberta had been ordered to have the uranium bomb ready for use on August 1st and the plutonium bomb as soon as possible after that. Ultimately. the uranium bomb was ready for use on July 31st.The uranium bomb was code named Little Boy. This name was suggested by Robert Serber and based on a character in the movie "The Maltese Falcon" from 1941. The bomb measured 9.8 feet in length, 28 inch in diameter and weighed 9.700 pounds. One of the men involved described it as an elongated trash can with fins. The uranium had a gross weight of 141 pounds, divided in two segments. Some sort of 6.6 inch gun with a barrel 6 feet in length was mounted inside the bomb. The largest chunk of uranium was the bullet weighing 84 pounds. This projectile had a hollow point and consisted of a number of rings. Behind the projectile were an explosive mixture and an electric detonator. The atomic bomb held numerous detonators that were activated in sequence. As soon as the bomb was dropped from the aircraft the process was triggered by the snapping of a few wires. One of the detonators was a radar system that activated the electric detonator of the bomb at an altitude of 2067 feet. This fired the gun and the bullet struck the uranium core creating a critical mass. At the moment the gun was fired, a device, made of polonium 84 – an initiator – inside the bomb started firing neutrons to get the chain reaction going. Beforehand, the scientists reckoned with an explosive force of between 8 and 15 kiloton. Only 0.0212 ounces of the uranium would ultimately be transformed into energy.

The plutonium bomb was code named Fat Man, a name derived from the same movie. The name was also based on the shape of the bomb. It measured 11 feet in length, 59 inch in diameter and weighed 10.295 pounds. In order to create a critical mass inside the bomb, use was made of an implosion. The detonator of the uranium bomb could not be used in the plutonium bomb as the chain reaction would not proceed according to schedule and too fast, resulting in relatively less explosive power. The plutonium was contained within an explosive device in the form of a lens. During the implosion, the material was compressed bringing the atoms closer together and so creating a critical mass. Lengthy research was conducted as to the correct shape and construction of this explosive device.

Fat Man contained 13.6 pounds of plutonium. The initiator of the bomb was made of polonium and beryllium and was designated urchin. The chain reaction would ultimately use 2.2 pounds of plutonium of which 0.0353 ounces would be transferred into energy. The parts of the plutonium bomb were transported by a number of converted B-29s. The plutonium core was transported in a C-54.

Definitielijst

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- Hiroshima

- City in Japan where the first operational atomic bomb was used on 6 August 1945.

- Manhattan Project

- The American development of the Atomic bomb during World War Two.

- Nagasaki

- Japanese city on which the United States dropped the second atomic bomb on 9 August 1945.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Images

First mission: Operation Centerboard

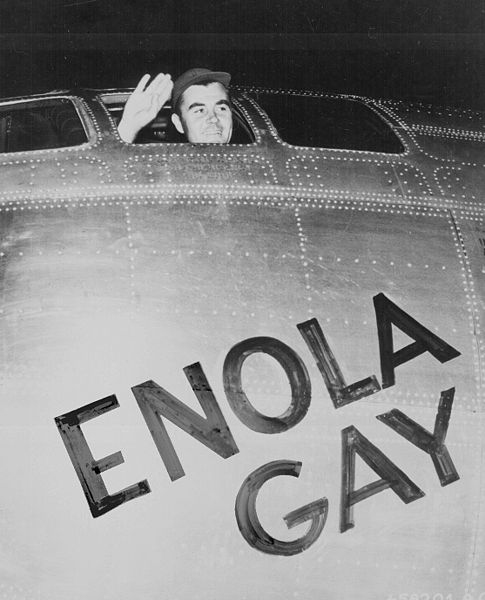

Enola Gay

The B-29 which was to fly the first mission, was selected by Paul Tibbets himself at the factory of the Glenn L. Martin Company. The aircraft was temporarily transferred to the crew of Captain Robert Lewis. Within the 509th Composite Group, Lewis was the most experienced pilot and he assumed he would be placed in charge of the mission to drop the first atomic bomb. He was therefore highly vexed when he found out that Tibbets was to fly the plane and he would act as co pilot. He also was uneasy about his regular navigator and bomb aimer being replaced. When Lewis discovered during the last pre flight check somebody had baptized "his" plane Enola Gay (after Tibbets’ mother), he became furious. Firstly because he did not approve of the name and secondly because he had not been informed in advance of this decision. A meeting took place between Lewis and Tibbets. What exactly was discussed is unknown but the result was that the B-29 retained the name. As a consequence, the relationship between these two men would remain uneasy, even after the war.On August 2nd, during a meeting with LeMay, it was agreed upon that Hiroshima would be no. 1 target. Two days later, the officers were instructed by Parsons about the coming mission. It was intended they would be shown a movie of the test explosion at Alamogordo but the projector was out of service. On August 6th, the last briefing took place at 00:00 hours. Next the chaplain said a prayer, especially written for this occasion. A few days before, Tibbets had been handed a number of cyanide pills. He and the crew were to swallow these in case they risked being taken prisoner by the Japanese.

The formation for the attack consisted of three aircraft. A fourth was held in reserve.

| Name: | Pilot: | Task: |

| The Great Artiste | Major Charles Sweeney | Carried scientific equipment in order to measure the force of the explosion and such. |

| No 91 / later designated as Necessary Evil | Captain George Marquardt | Carried photografic equipment to record the explosion. |

| Enola Gay | Colonel Paul Tibbets | Carried the bomb. |

| Top Secret | Captain Charles McKnight | Was held in reserve on Iwo Jima. |

- Colonel Paul Tibbets, pilot and captain

- Captain Robert Lewis, 2nd pilot)

- Major Thomas Ferebee, bomb aimer

- Captain Theodore van Kirk, nicknamed Dutch, navigator

- Captain William Parsons, armament specialist, commander of the mission

- First Lieutenant Jacob Beser, radarofficer

- Second Lieutenant Morris Jeppson, assistent armament specilaist

- Technical Sergeant George Caron, call sign Bob, tailgunner

- Technical Sergeant Wyatt Duzenbery, flight engineer

- Sergeant Joe Stiborik, radar operator

- Sergeant Robert Shumard, assistent flight engineer

- Private First Class Richard Nelson, radio operator

Destination: Hiroshima, Special Bombardment flight 13

At 01:37 hours, the scout aircraft took off. Possible targets for that morning were Hiroshima, Kokura and Nagasaki. The Straight Flush, commanded by Major Claude Eatherly set course for Hiroshima to check on the local weather conditions. Major John Wilson in Jabbitt III did the same for Kokura. Major Ralph Taylor flying the Full House reconnoitered the situation over Nagasaki. Just before the Enola Gay took off, Lewis addressed the crew: "Listen, you guys. This bomb costs more than a flattop. Don’t spoil it. We produced it. We’re going to win the war so don’t screw up."Departure of the Enola Gay was turned into a veritable media circus. No less than 100 persons were present, including journalists, high ranking military and scientists. The engines were started at 02:27 hours. Take off weight was 149.914 pounds, exceeding the limit by 16.755 pounds. The take off began at 02:45 hours. Take off and the outward flight proceeded without too much problems. The Great Artiste took off two minutes behind the Enola Gay, followed two minutes later by No. 91. A little before 03:00 hours, Parsons prepared the bomb. One of the things he did was placing the explosive powder.

In the night of August 5th to 6th, the air raid alarm was sounded three times in Hiroshima. Each time however, the all clear was sounded as the anti aircraft batteries had not observed any aircraft. At 04:55 Japan time (1 hour behind Tinian time) the Great Artiste and No. 91 joined the Enola Gay over Iwo Jima. At 06:30 hours, 2nd Lieutenant Morris Jeppson exchanged the green safety plugs for red plugs closing the electrical circuit to the detonator and definitely arming the bomb. A few moments later, Tibbets addressed the crew by intercom. He told them the aircraft was carrying the first atomic bomb. A number of crew members were still ignorant of this but they did have an idea. On 06:40, the Enola Gay climbed to 31,000 feet, the altitude the bomb was to be dropped from.

Shortly after, a message from the Straight Flush was received. She reported: "Cloud cover less than 3/10 at all altitudes. Advise bomb first target". The other scouts reported good weather conditions over Nagasaki and Kokura as well. Tibbets radioed the message "first" to Iwo Jima. By appearing over the city, the Straight Flush had alerted the Japanese anti aircraft defenses and the alarm was sounded again. At 08:00 hours, the all clear was sounded. The Japanese assumed the aircraft they observed were on a reconnaissance mission. At 08:09 hours, Tibbets started his final approach to the dropping point.

At 08:12 hours, the Enola Gay and the other B-29s of the formation were spotted by the Japanese look out. The message was relayed but they did not manage to sound the alarm on time. At 08:14 nine out of 12 crew members of the Enola Gay put on their welding goggles. Tibbets and Ferebee did not as their vision would be impaired too much. No interference by Japanese radar was detected. Ferebee started the synchronization of the aiming device. This warning signal, a high pitched tone was picked up by the other B-29s indicating the bomb would be released within the next 60 seconds.

At 08:15:17, the bomb doors of the Enola Gay popped open automatically. Freed of its dead weight of almost 5,000 pounds, the aircraft shot almost 10 feet upwards. Tibbets flung the plane in a steep 155 degrees banking turn. The timing mechanism flipped the first switch. The next seconds, the men looked at their watches anxiously, wondering whether the bomb would explode at all. At 8,800 feet, the air pressure switch closed. 43 seconds after the release of the bomb, at 08:16 exactly, at an altitude of 1,900 feet, Little Boy exploded with a loud bang. The bomb overshot the target, the Aioi bridge by 885 feet and exploded over the Shima clinic. The measurements taken to determine the force of the explosion showed varying results. Most were between 13 and 16 kiloton.

Definitielijst

- Hiroshima

- City in Japan where the first operational atomic bomb was used on 6 August 1945.

- Nagasaki

- Japanese city on which the United States dropped the second atomic bomb on 9 August 1945.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

Images

Atomic bomb on Hiroshima

Explosion

A purple colored light grew into an enormous fire ball of hundreds of feet across. The instruments in the cockpit of the Enola Gay were illuminated by the flash of the explosion. A thin mist arose. A giant mushroom cloud darkened the sky and rose to an altitude of 59,000 feet. The temperature in the center of the explosion rose to 25 million degrees Celsius, at ground level, it was 4,000 degrees. The shockwave of the bomb, created by the superheated air, had a strength of 5 psi and destroyed every building within a 5,250 feet radius. The wave was so powerful that aircraft on the city’s airport were bent like paperclips. An eyewitness later declared about this: "When the shockwave came, I was hurled through the room. I was flung from wall to wall and from the ceiling to the floor. My body was thrown around as if it were a ball." The pressure waves of the atomic bomb flung the Enola Gay upwards. The force was so enormous Tibbets initially thought a shell had exploded close to the aircraft.The fireball of the explosion measured 1,213 feet across. The heat was so intense, clothing and skin were fused together. Potatoes were cooked in the ground and granite surfaces were polished. The heat wave caused spontaneous combustion at a distance of over 2,000 yards. This effect was enhanced because all gas and power lines had been severed. The numerous fires that had erupted all over the city evolved into a giant fire storm, 2 miles across. The wood of shattered buildings was an ideal fuel, just as the thousands of wood fueled stoves the Japanese used for cooking their breakfast. Attempts at extinguishing the blaze were useless especially so as the main water lines were severed in thousands of places. Most people in town fell victim to this fire storm. Hundreds of persons who had sought shelter in the city’s water basins were boiled alive. Survivor Sadao Hirano said about the explosion: "Almost my entire body was burnt in three or four seconds. My skin was hanging loose. I wanted to take a drink but I couldn’t."

Consequences

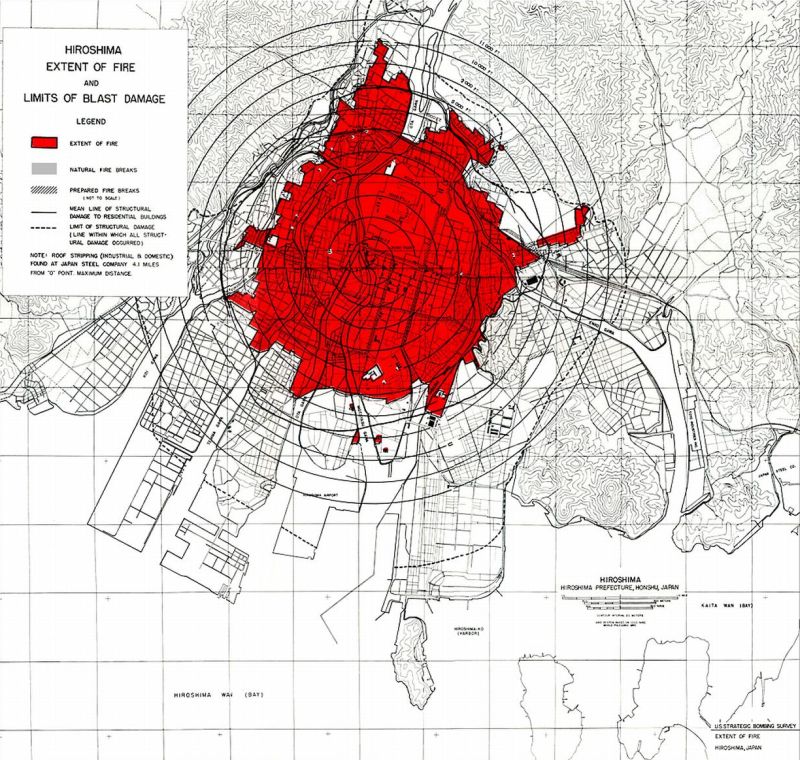

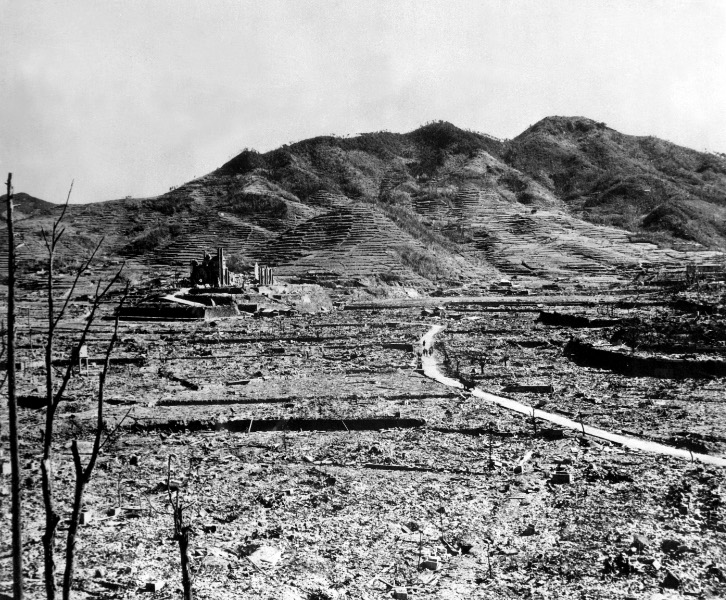

The nuclear explosion triggered an enormous amount of gamma and neutron radiation. In a radius of 0.8 miles, this level of radiation was lethal. 6,000 survivors of the fire storm later died from this radiation. About 30 minutes after the explosion, black rain came down in the western suburbs of the city. The droplets consisting of ashes and smoke were highly radio active and contaminated a large part of the city. About 30% of the survivors were injured by the radio active fall out. Many of them died of radiation disease during the next weeks. Others died years after the war of the cancer they had contracted from the radiation.Discussion about the number of victims, resulting from the explosion, is still going on. Most sources report that out of the 260,000 inhabitants of the city, some 78,000 were killed instantly, about 20,000 of them soldiers. Over 70,000 people were injured. Most of the deaths occurred in an area of about 46.332 square miles around the Aioi bridge. After the war long and extensive research by scientists of the Manhattan Project resulted in 66,000 persons killed and 69,000 injured. 62,000 out of the 90,000 buildings in the city were destroyed. All facilities were severely disrupted. Out of the 200 physicians in the city, 180 were either dead or injured. Only three of the 55 hospitals and First Aid stations in town were still operational. Eyewitnesses later reported hordes of living zombies wandering about the city in search of medical help or shelter. They were bleeding from many wounds, hairs and clothing had burned away and they were frequently burnt horrendously. Of the passengers in the tram in Hiroshima not much more was left than some black cinder.

Kinu Kasata, an inhabitant of the city, described the view of Honkawa primary school as follows: "All pupils who had assembled in the school garden for the morning break, were burned black, squatting in orderly rows, motionless." Most of the deaths occurred on what was called Ground Zero, the castle of Hiroshima, 984 yards from the epicenter. The shadows of the bodies, literally evaporated, of hundreds of Japanese soldiers and an American prisoner of war, who were doing their daily physical exercises, were etched on the training ground. Thousands of people working on the fire trenches underwent the same fate. At Kempei Tai headquarters, at just 437 yards from the epicenter, 12 American prisoners of war were interned. Most of them died instantaneously although it is said that a few of them were murdered in revenge later in the day by their guards or furious citizens.

The B-29s circled around the city at a distance of 11.18 miles to observe it. Tibbets asked his men to describe their feelings. According to his fellow crew members, Lewis said: "My God, look at that." After the war he declared he had said: "What have we done?" Beser declared in his turn: "It is pretty horrible but what a relief it worked." At 398 miles distance, the mushroom cloud could no longer be seen from the Enola Gay. At 14:58 hours, the aircraft landed on Tinian without any problem. They received a grand reception. Spaatz awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross to Tibbets on the spot.

Aid and rescue

Help in Hiroshima commenced slowly. Initially, many Japanese displayed an apathic attitude. A few hours later they swung into action. Schools and tram stations were used to assemble the huge numbers of victims. The Asano library was turned into a morgue. The suicide vessels were lashed together to form large rafts to evacuate the numerous injured from the city. Many people had sought shelter in the river, they were taken to the military hospital in Ujina. As the Mayor had died, Field marshal Shunroku Hatta took command of the city.It took until late afternoon of August 6th before the Japanese government was aware of what had happened in Hiroshima. The first indication was that the local radio station had stopped transmitting and despite furious attempts, it was impossible to contact the city. Only after a scout plane had been dispatched from Tokyo to Hiroshima and had transmitted its report, it began to dawn on the Japanese government what had happened to the city. On August 7th, Harry Truman made an announcement on radio. He stated that 16 hours before a single aircraft had destroyed the city of Hiroshima with only one bomb. He stated that the atomic bomb enabled the Americans to destroy the entire Japanese production capacity in every city. He threatened to unleash a "rain of ruin from the air," against Japan if she did not accept the declaration of Potsdam.

The same day a number of Japanese scientists visited the city and concluded it had been attacked by an atomic bomb, although other scientists doubted this conclusion. Subsequently, the Japanese government decided she was ready to capitulate under four conditions: maintaining the godlike status of the Emperor, the responsibility for the demobilization should be in the hands of the headquarters of the Imperial Army, no occupation by the Allies of the Japanese home islands, Formosa (today Taiwan) and Korea – both areas had been occupied by Japan since 1895 and 1910 respectively – and persecution of war criminals was to be left to the Japanese judiciary system. It was attempted to enter negotiations through the Soviet Union. However, surrender was furthest from the minds of elements within the armed forces. The chief of the General Staff, Soemu Toyoda argued that two or three atomic bombs might be ready at best and that more destruction might follow but the war would be continued nonetheless. On August 8th however, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and one day later, the Red Army launched the invasion of Manchuria that had been occupied by Japan.

On August 7th, a meeting was held between Rear Admiral William Purnell (the U.S. Navy representative to the Manhattan Project), Captain William Parsons, Colonel Paul Tibbets, General Carl Spaatz and Major-general Curtis E LeMay. Parsons, Purnell and Farrell were sometimes called the Tinian Joint Chiefs. They possessed full power of attorney on military matters and could make decisions independently. On August 7th, it was clear that the Japanese were taking no steps in the direction of capitulation. During the meeting of these five officers, it was decided to drop a second bomb on Japan. The next nuclear attack was scheduled for August 11th. It had been agreed before that Major Charles Sweeney would fly this mission. Sweeney’s own plane was the Great Artiste. During the attack on Hiroshima, she had been carrying scientific instruments and it was a lot of work to transfer all this equipment to another plane. When the weathermen predicted bad weather coming in on the 10th, the attack was moved up by two days to August 9th and it was decided that Sweeney would fly the mission in another B-29, the Bockscar.

Definitielijst

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- heat

- High-explosive anti-tank warhead. Shaped charge projectile to punch through armour. Used in e.g. bazooka or in the Panzerfaust.

- Hiroshima

- City in Japan where the first operational atomic bomb was used on 6 August 1945.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Manhattan Project

- The American development of the Atomic bomb during World War Two.

- marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Images

Atomic bomb on Nagasaki

Bockscar and her crew

On August 9th, at 03:47 Tinian time Bockscar, flown by Charles Sweeny, took off for the attack on Kokura. Nagasaki had been marked as the secondary target. The flight crew consisted of the following men:

- Major Charles Sweeney, pilot)

- Captain Charles Donald Albury, 2nd pilot)

- Second Lieutenant Frederick Olivi, 3rd pilot

- Captain James van Pelt, navigator

- Captain Kermit Beahan, bomb aimer

- Master Sergeant John Kuharek, flight engineer

- Staff Sergeant Raymond Gallagher, assistant flighht engineer

- Staff Sergeant Edward Buckley, radar operator

- Sergeant Abe Spitzer, radio operator

- Sergeant Albert DeHart, tali gunner

- Commander Frederick Ashworth, armaments specialist

- Lieutenant Philip Barnes, assistent armaments specialist

- First Lieutenant Jacob Beser, radar officer)

Prior to departure, all procedures to arm the bomb had been completed. Only the safety plugs had yet to be removed. The intended rendez-vous over Yakushima with Big Stink, flown by Major James Hopkins and Great Artiste flown by Captain Frederick Bock, did not proceed according to plan. The Big Stink was not at the designated location and altitude. Due to the imposed radio silence, communication between the two aircraft was impossible. In violation of his instructions, Sweeney decided to wait more than 15 minutes. After having circled around for 45 minutes, he decided to continue the attack anyway without Big Stink. On arrival over Kokura, the planned target in the city, the Arsenal (a Japanese army depot for equipment and munitions) was poorly visible due to the cloud cover. This was caused, besides other things, by the smoke emanating from a conventional bombing of the nearby city of Yahata. During the next 50 minutes, Sweeney made three bomb runs over the city but each time, Beahan decided not to release the bomb because he was unable to identify the target.

Bockscar came under fire from Japanese anti-aircraft defenses and fighters. The fuel supply decreased quickly. This was a problem as the pump of the reserve fuel tank was out of action. This had been discovered by the flight engineer before take off but the pump could neither be repaired nor exchanged as the attack could not be postponed. Neither could the atomic bomb be transferred to another aircraft because of the risks involved and also because this would have taken several hours. Considering the critical fuel situation, Sweeney and Ashworth decided at 10:30 to head for Nagasaki.

Explosion

At 07:50 on August 9th, the air raid alarm was sounded in Nagasaki; at 08:13 the all clear was sounded. At 10:53, Japanese radar picked up two B-29s. It was assumed these aircraft were on a reconnaissance mission so no alarm was sounded. Due to the remaining amount of fuel, it was clear in advance that only one run could be made over the city. Sweeney suggested to bomb by radar as he assumed there was cloud over Nagasaki as well. Ashworth agreed but the bomb aimer Initially refused although there was no real alternative. Once over the city, visibility proved to be sufficient though.Beahan released the bomb over the city’s stadium, assuming this was close to the designated target, the railway station. However, the stadium and the station were 1.8 miles apart. This caused the bomb to come down over the valley formed by the river Urakami, which meant the explosive force was contained by the surrounding hills but it did explode right over the industrial center of Nagasaki. The bomb was released on three parachutes. Fat Man exploded at 11:02 at an altitude of 1,650 feet. Ashworth described the detonation as follows: "The bomb exploded in a blinding flash and an enormous column of smoke whirled in our direction. From this column of smoke, a mushroom of grey smoke, lit up by red flames, rose to an altitude of 40,000 feet in less than eight minutes. We saw the shroud of black smoke through the cloud, ringed by fire over what once had been the industrial heart of Nagasaki.

The bomb generated an estimated explosive force of 21 kiloton and destroyed 44% of the city, an area of about 1.15 square miles. Over 50,000 buildings were destroyed or severely damaged. In a radius of 1.6 miles, even steel frames of factories were destroyed. All buildings within a radius of 1.49 miles were severely damaged. Even buildings at a distance of 4.35 miles collapsed. The hills at 1.24 miles distance were heated up sufficiently to change their colors. On seeing this, eye witnesses stated it looked like autumn had set in early. The crews of the observing B-29s reported five shock waves. Bockscar was only able to circle the city once as she was running out of fuel and so she was forced to land on Okinawa.

In an area south of the epicenter, up to a distance of 1.86 miles, fires erupted in numerous places. The shape of the city prevented a fire storm from breaking out. Discussion about the number of victims of the explosion is still going on and vary between 22,000 and 75,000. The most likely estimate ranges from 35,000 to 40,000. Scientists of the Manhattan Project concluded 39,000 people dead and 25,000 injured as a result of the explosion. After investigation, the Japanese themselves arrived at a verified number of just 23,753 dead, 1,927 missing and 23,345 injured. Most deaths occurred in the industrial heart of the city. In the Mitsubishi munitions factory, 6,200 out of a total of 7,500 workers perished. As a result of the attack, 150 Japanese soldiers died along with eight Allied prisoners of war: seven Dutch and one British.

Postman Sumiteru Taniguchi stated: "I heard an aircraft. It was strange because the air raid alarm had been lifted and then I looked at the city… I stood up and looked around. All around me houses had been destroyed. Only the last house, where I had to deliver mail, had been spared. I looked at my hands. The skin on my left arm, from my elbow to my fingers, was in tatters. Something blackish stuck to my hands."

Aid and rescue

Camp Fukuoka 14B was at 1.1 miles from the epicenter. On August 9th, a number of Dutch prisoners of war was charged with digging shelters against future air raids. Other camp inmates were busily clearing debris from the attack of August 1st. The men spoke of a lightning flash that penetrated everything and blinded them. The sun was darkened by the dust of the explosion and colored blood red. Bolts of fire shot in all directions. The camp buildings were destroyed by the shock wave. Everything was flattened. Only the steel skeletons of the factories still stood. The blast of the explosion was so powerful, all loose clothing was torn away. A Japanese guard, who had literally been scalped, was blown into the corridor the Dutch were working in. Three Dutchmen, who were having a short break, sustained severe burns. Other men who were clearing debris were burnt alive.The Dutchmen organized the evacuation of their injured themselves. Cadet Paul Jolly took charge. The were taken to a recently dug shelter. Franciscus Snijders wrote about salvaging the injured: "One of the cooks was extracted from the wreckage of the kitchen with a hole in his forehead from which his brains protruded. He was nearly dead. Then we went to the factory. Those with burns looked horrendous. Their skin hung in tatters from their heads and bodies. Underneath, enormous blisters developed causing much pain and making the faces look ghastly." Inmate P. Blok described how a severely injured Japanese soldier was kicked and beaten by his comrades as a servant of the Emperor was not allowed to show he was in pain.

Private M.J.L. Meegens got trapped under a steel beam of a crane in the factory where he had been working that day. Various prisoners attempted to free him but they were forced to abort their attempts as heat and smoke made further work impossible. His last words were, it is said: "Leave me, You go on." His charred body was found the next day. The Dutch inmates fled to the hills, climbing higher and further. They spent the night in a building in a higher part of the city that had suffered less damage. A day later, the inmates returned to the camp while others stayed in the hills. Later, they were herded together by the Kempei Tai and imprisoned again.

The fire department kept a cool head and started extinguishing the fires. Governor Nagato acted quickly as he had heard the stories about Hiroshima. He quickly called for trains to evacuate the injured. The dead were cremated to prevent diseases from spreading. The Dutch prisoners were given this task. On of them stated: "You had to pick up partially maimed body parts with your bare hands and take them to funeral piles." Symptoms of radiation disease started to appear. Persons began suffering from drowsiness, diarrhea, fever, vomiting and inexplicable bleeding. Others lost their hair, their mouth became inflamed causing their teeth to fall out. Deaths as a result of radiation disease occurred after a week. Even eight weeks on, people died. In Hiroshima the level of radiation had risen to 25 Röntgen; in Nagasaki the gamma radiation even reached a peak of 110 Röntgen.

Definitielijst

- heat

- High-explosive anti-tank warhead. Shaped charge projectile to punch through armour. Used in e.g. bazooka or in the Panzerfaust.

- Hiroshima

- City in Japan where the first operational atomic bomb was used on 6 August 1945.

- Manhattan Project

- The American development of the Atomic bomb during World War Two.

- Nagasaki

- Japanese city on which the United States dropped the second atomic bomb on 9 August 1945.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

Images

The aftermath

Japan surrenders

Plans were ready to drop even more atomic bombs on Japan. On August 10th and 14th, two more plutonium bombs would be shipped to Tinian. The next attack was scheduled for August 19th. These plans were overtaken by the events however.As mentioned before, the Soviet Union had declared war on Japan on August 8th. A day later, the Supreme War Council convened in Tokyo. The Japanese prime minister and the secretary of foreign affairs advocated surrender. The military commanders refused however and stuck to three conditions for surrender (unacceptable to the Allies): Tokyo was not to be occupied, Japan was to disarm her forces and persecute her war criminals herself. The discussion stretched on and on. In the end, in the night of August 9th to 10th, the unique decision was taken to ask the Emperor for advice.

In a subsequent meeting with his civilian and military advisors, Emperor Hirohito declared that unconditional surrender should be accepted as long as the position of the emperor would be guaranteed. After yet another meeting, the Japanese cabinet agreed. The message was passed to the Allies on August 10th. On August 14th, again a meeting was held during which the American response was discussed. Among other things, the Americans demanded the emperor be subordinate to the Allied Supreme Commander. Hirohito accepted the American answer by saying: "We shall have to accept the unacceptable and bear the unbearable."

That same day, Hirohito recorded a radio speech to be aired on August 15th. In order to prevent this, a number of Japanese officers attempted a coup but this revolt was quickly quelled. In his speech, the Emperor said: "The enemy has a new and terrible weapon at his disposal with the power to destroy many lives and inflict incalculable damage. If we are to fight on, this will not only result in total collapse and destruction of the Japanese people but it will also lead to the extinction of human civilization. Now that this is the case, how do we save two million of our citizens or do we do penance to the holy spirits of our ancestors? This is the reason why we have accepted the conditions in the joint declaration of the Allied powers."

After the war, Hirohito considered the atomic bombs the major reason for surrender. According to him, only then surrender became negotiable because of the situation being what it was. On September 2nd, 1945 the official signing of the capitulation of Japan took place aboard the American battle wagon U.S.S. Missouri. The war in the Pacific was over too.

Discussion

After the war, the deployment of the atomic bomb has been questioned many times. Opponents argue that Japan would have surrendered without the atomic bomb anyway and that use of this weapon only caused needless suffering of the civilian population. It is certain the Empire would have capitulated in the long run as Japan’s military situation was in fact untenable from early 1945 onwards. The question then remains how long this would have lasted. The Americans were working on plans for an invasion of the Japanese home islands. Losses of over one million servicemen were taken into account. This number is probably exaggerated but even then, there is no doubt about an invasion entailing serious losses. The Japanese Imperial army still numbered over two million men, moreover, from April 1945 onwards, preparations were started for the establishment of a civil militia, the National Voluntary Combat Corps which would number no less than 28 million men.During the conquest of Saipan and Okinawa by the Americans, Japanese military had forced the civilian population to commit suicide on a large scale. The Americans feared a repetition of this scenario during an invasion of Japan itself. In fact, there were no other alternatives to bring Japan to her knees. A blockade of the country, as suggested by some, would also have led to death by starvation of thousands of Allied prisoners of war and millions of Japanese civilians, before it would have produced any effect; if at all. Others argue Japan would have capitulated quickly anyway in case the Soviet Union had declared war on Japan but even this is far from certain. The battle could have stretched on for months with tens of thousands dead as a result. The invasion would have taken place anyway, even after the Soviet Union had declared war on the country as preparations for the American plans were already well advanced.

Deployment of the atomic bombs must be considered against the background of the time in which they were deployed. In 1945, there were only a few who denounced the use of it. Politicians and the majority of the scientists in the U.S. backed the decision. It would have been strange not to do anything with the weapon as so much money had already been spent on it. The majority of the American population agreed to the deployment of the atomic weapon. In November 1975, during a visit to the U.S., Hirohito declared: "I pity the civilians of Hiroshima but the attack could not be prevented as the war was still raging at the time."

Victims and survivors

Even long after the war, the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki continued to claim victims. Those who had been subjected to the radiation of the bombs on August 6th and 9th risked and still risk contracting cancer and other diseases. Even today, the ultimate number of victims cannot be determined precisely, also because the Japanese registration system did not function properly any more towards the end of the war. The remains of most victims have been cremated in the days after August 6th and 9th in order to prevent diseases from spreading. Also, the remains of many people have never been found. It was often said about people that died in Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the war their death was caused by the radiation they had been subjected to but this is far from certain however. A number of victims, including post war deaths that is often mentioned amounts to 140,000 in Hiroshima and 70,000 in Nagasaki. The Guinness Book of Records arrives at a total of 155,200 dead in Hiroshima during and after the war. A tablet on the monument at the epicenter in Nagasaki shows a total of 73,884 dead.In Japan, the survivors of the atomic bombs are called Hibakusha (those who received the bomb). After the war and even today in modern Japan, they and their grandchildren face discrimination. It was very difficult for a survivor to find a job or a marriage candidate as they were and still are considered unclean. In Hiroshima and in Nagasaki, strong peace movements are active. In both cities there is a peace park in commemoration of the survivors. The Genbaku Domu, the remains of a building that partially survived the explosion is a well known monument in Hiroshima.

Charles Sweeney passed away on July 18th, 2004. Tibbets died of a heart attack on November 1st, 2007. After the war, Sweeney and Tibbets have always defended the deployment of the atomic bomb. In their opinion, the capitulation of Japan was made possible in that way and the war was won. Theodore van Kirk died July 28th, 2014. The last crew member of the Enola Gay passed away with him. In 1955, in an interview with the New York Times, Van Kirk stated: "Under the same circumstances, I would do it again. We were at war for five years already. We were fighting an enemy who had the reputation never to surrender and never to accept defeat. It is difficult to talk about war and morale in the same sentence. During the war, so many questionable things have happened. Where was the morale during the bombing of Coventry, the bombing of Dresden, the Bataan death march, the rape of Nanking or the attack on Pearl Harbor? I believe that if a nation is at war, it must have the guts to do what has to be done in order to end that war and save as many lives as possible."

Definitielijst

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- Hiroshima

- City in Japan where the first operational atomic bomb was used on 6 August 1945.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Nagasaki

- Japanese city on which the United States dropped the second atomic bomb on 9 August 1945.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Images

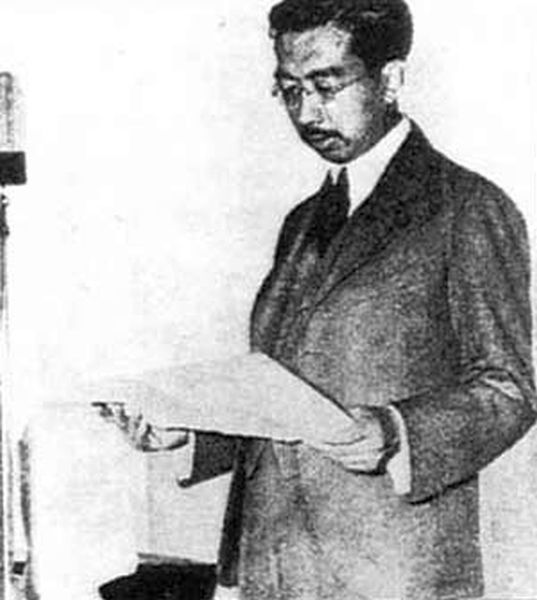

On August 14th, 1945 Emperor Hirohito records the radio address, announcing Japan’s unconditional surrender. Source: World War 2 database.

On August 14th, 1945 Emperor Hirohito records the radio address, announcing Japan’s unconditional surrender. Source: World War 2 database.Information

- Article by:

- Wesley Dankers

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 13-01-2017

- Last edit on: