Childhood years and pre war career

Introduction

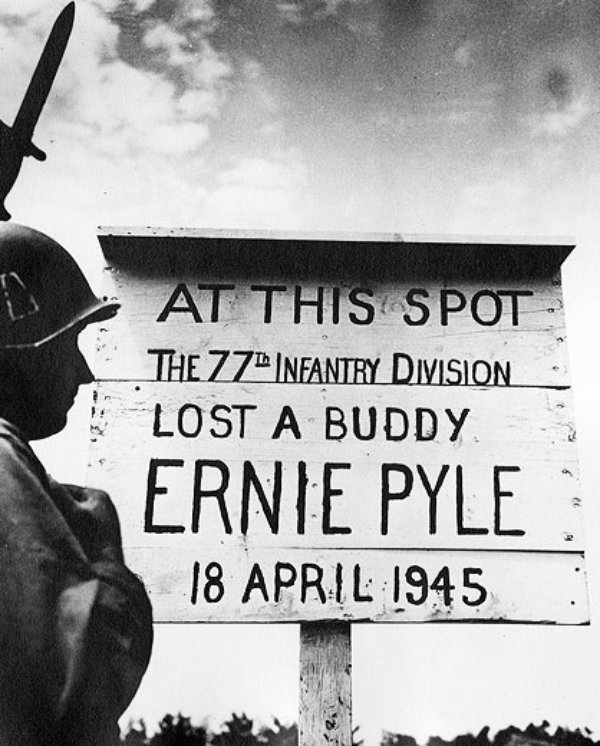

"At this spot, the 77th Davison lost a buddy". This text appeared on a wooden sign on a field grave on the Japanese island of Ie Shima on the Okinawa islands in the East-Chinese Sea. On April 18, 1945, while the battle for Okinawa raged in full, an American died for whom this sign was erected. He was neither a rifleman nor a Marine but a civilian. Not just any civilian; at the front as well as in the United States, he was the most popular war correspondent and Ernie Pyle was his name.

Country boy

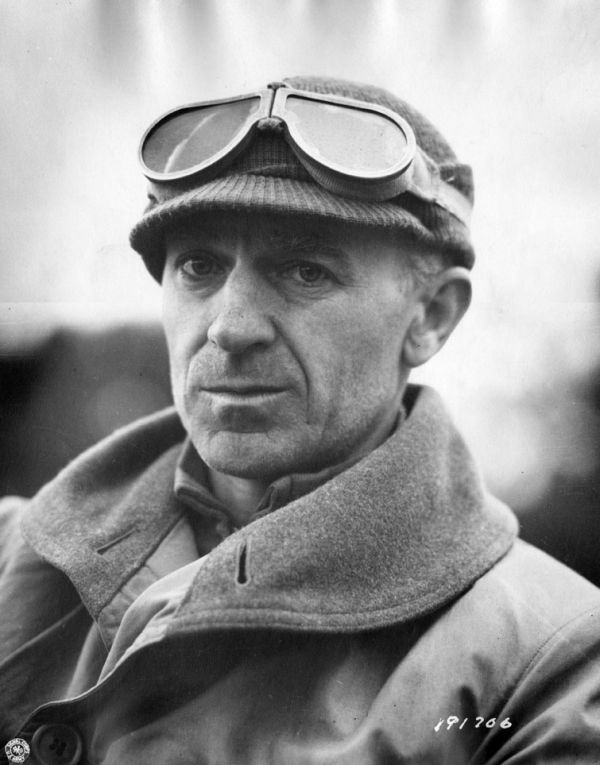

The road to national fame was a long one for Ernest Taylor Pyle, born August 3, 1900. His place of birth was a desolate farmhouse in the vicinity of the small village of Dana, 850 inhabitants in western Indiana. Endless agricultural fields, bisected by arrow straight roads made up the less inspiring landscape of Ernie’s youth. His father Will, a taciturn man, was the tenant of the farm as he could not find employment as a carpenter. Ernie’s mother, Maria Taylor-Pyle was quite different from her submissive husband. She was an outgoing and social farmer’s wife who pulled all the strings at home. Ernie was the couple’s only child. He was a dreamer who devoured adventure stories but he also worked hard at ploughing the land. Probably like so many of his contempories in a state with a yearly highlight, the Indianapolis 500, he dreamt of a career as racing driver.

At school, Ernie was an outsider, a country boy who looked up at boys from the city. Ernie got his first chance to escape from dreary rural life when America entered World War One in 1917. To his dismay, he was one year below the age limit. One month after he finally joined the Naval Reserve in 1918, the armistice had already been signed. Ernie was yet to see the front during the next world war. In 1919, the intelligent youngster started his curriculum at Indiana University in Bloomington. He selected economics as his main subject but in addition he attended classes in journalism. During his student period, he made contributions to the student paper "Indiana Daily Student." His journalistic example was Associated Press reporter Kirke Simpson who was awarded the Pullitzer prize in 1922 for an article on the burial of the "unknown soldier" at Arlington National Cemetery.

Restless young man

In order to broaden his horizon, Ernie traveled up and down the country during summer holidays. In the spring of 1922, he crossed the national border when he accompanied the university basketball team during its sea voyage to Japan. As he was not in possession of the required documents to enter Japan, he continued his voyage through China and the Philippines. With just one semester left, he dropped out of university, possibly following an incident with a teacher. In January 1923, he applied for the real journalistic work to the editorial staff of the Herald in La Porte in northwestern Indiana. His journalistic high during his tenure of only four months with the local paper was probably his infiltration in a meeting of the racist Ku Klux Klan.

In May 1923, Pyle made the transfer to "The Washington Daily News", a tabloid established in 1921 by the publishing firm of Scripps-Howard. The young journalist, who sometimes went to work in a logging shirt and woolen cap, was considered a little eccentric by his colleagues. However, he proved himself an excellent chief editor giving someone else’s work the drive the editor in chief wanted. Within a year, the restless young man had enough of the routine and he resigned in order to work as a sailor in the Caribbean for the next two years. Back in the U.S., he married Geraldine Siebolds from Minnesota whom he had met during his stay in Washington. Together with Jerry, his wife’s nickname, he traveled all across the U.S. in a T-Ford and a shelter. Their voyage ended in New York where they were to stay for the next 16 months and Ernie found employment as chief editor of "The Evening World" and the "New York Post."

Ernie could not find his feet in the Big Apple. Christmas 1927, he and his wife returned to Washington after a befriended editor in chief had made him an offer to return to the editorial staff of the Washington Daily News. This friend was Lee Graham Miller and until Ernie’s death, he would be an important associate and business representative of his. Manning an editor’s desk again did not appeal to Ernie at all and therefore he got Miller’s permission to write columns on aviation, apart from his function of editor in chief of telegraph messages. That turned out to be a lucky shot as everything pertaining to aircraft could count on lively public interest. When Ernie’s first column appeared in March 1928, aviation pioneer Charles Lindbergh had been the first to cross the Atlantic from New York to Paris non-stop ten months before. Civil aviation was developing fast and Pyle became a welcome visitor of air fields in Washington and surroundings.

Pyle felt like a fish in water among the air field personnel and the pilots. He was accepted as one of them for his straightforward and unpretentious attitude. His columns were widely acclaimed by a diverse audience for his informal language and his special attention to human interest. They soon appeared on a daily basis and later on, Pyle was appointed aviation editor for all the papers published by Scripps-Howard. Among the prominent persons he met as an aviation journalist were Amelia Earhart, the first female pilot to cross the Atlantic Ocean in 1932 and who did the same in 1935, the first human to cross the Pacific Ocean. As much as he liked being a columnist, in the spring of 1932, Pyle did accept the offer to become editor in chief of the Washington Daily News. He would hold this function for three years but he did not really feel at home in it. "It is a short-cut to insanity," he remarked once, referring to the organizational aspect.

A roving existence

It was far from obvious Ernie would spend the rest of his career as editor in chief of the Washington Daily News. He missed the writing that gave him the most satisfaction. In private life, things did not go too smoothly either. Jerry was pregnant but opted for abortion while Ernie would have liked to have kept the child. He was worried about his spouse who retreated ever further into herself and was fighting an alcohol addiction and psychic problems. Therefore, he changed course drastically in 1935. Inspired by a three-week journey through America, which had yielded good columns, Ernie got permission to write a six-day column while traveling which would appear in all Scripps-Howard publications. From 1935 to 1942, he and his wife crisscrossed a large part of the western hemisphere in a Dodge Convertible Coupe. The couple visited each American state and called on special geographical locations such as the lowest point of the United States in Death Valley and the southernmost point of Key West (Hawaii joined the Union as late as 1959). Everywhere he turned up, Pyle spoke to local representatives from all walks of life: young, old, poor or rich.

Pyle was to write 2.5 million words during his years as roving columnist. "News does not have to be important but has to be interesting," was his adagium. "Always look for the story, for the unexpected human emotion in the story. Try to write the way humans talk." He wrote in the "I" form and never raised himself above the people he wrote about. As a neutral observer, he reported on American society at the time of the Great Depression and President’s Roosevelt’s New Deal. (Bio Roosevelt). His stories about the freedom to travel to any corner of the nation, about common Americans holding on in difficult times and about rural living, touched the American souls in a fast changing period of modernization and urbanization. By his expressive way of writing, he took his readers to places where they had never been themselves. His columns were very popular among a broad section of readers and from the spring of 1939 onwards, they also appeared in other major newspapers outside the Scripps-Howard stable.

Ernie and Jerry enjoyed their roving existence. Ernie however suffered from the pressure to deliver his columns on time and the fear whether they were good enough. Abusive use of alcohol was his answer to the stress, the despondency and exhaustion he struggled with. This tenacious worry and the fear of success was to remain with him throughout his entire career as an author. Quitting his columns was no option to him nevertheless. After a tour of two months through Central America he returned to the U.S. in February 1940. Six months before, the armies of Adolf Hitler (Bio Hitler) had invaded Poland, unleashing a new global war. Pyle had wanted to travel to Europe before in order to report on the war and he pressed home his plan towards the end of 1940 but not before he had a house built in Albuquerque, New Mexico with a view on the Rio Grande Valley. He hoped Jerry could find peace there because when they had ended their roving existence, she again struggled with psychic problems that would deteriorate over time, despite the new house.

Definitielijst

- infiltration

- Quiet incursion into enemy lines prior to an attack.

Images

The first years of the war, 1940 to 1943

London during the Blitz

On December 9, 1940, Ernie Pyle arrived in England; the only West-European country still holding out against Nazi-Germany. The American wanted to experience the Blitz on London, the bombardments by the Luftwaffe on the British capital. The city had been bombed for the first time on September 7, 1940. After having wandered around the city for days without anything happening, Ernie witnessed his first bombardment on December 29. It was one of the most devastating bombings that would hit London during which over 160 civilians perished. From a high balcony he watched the scene over the skyline of he city for hours. In an article he described it as: "the most beautiful view I have ever seen." It was his honest expression how he experienced the brightly colored explosions and the sea of flames, as if he was watching a lavish show of fire works on Independence Day. At the same time he expressed his great sympathy and admiration for the steadfast attitude of the citizens of London during the Blitz in his columns. In the U.S., his articles were received positively. His article on the London bombing was taken over by the prestigious New York Times.

Back in Albuquerque in March 1941, Ernie was welcomed like a celebrity. In the streets everyone wanted to shake hands with him or to have pictures taken. Meanwhile Jerry went downhill: she made an attempt at suicide and suffered from a severe stomach ulcer caused by alcohol poisoning. Ernie took leave from September to December 1941 in order to take care of her although there was little he could do for her in her situation. Subsequently he made plans for a long journey that would take him to China, the Dutch East Indies and Australia among other countries. He did not get beyond San Francisco though as the authorities refused to give him permission to fly to Honolulu. That had nothing to do with himself but it probably was the revenge of the Department of Foreign Affairs over negative articles of Scripps-Howard on Roosevelt’s foreign policy. In the first few months of 1942, Ernie got into a depression and in April he divorced his wife.

As he was thwarted to travel to Oceania and Southeast Asia, Pyle decided to report for service in the navy, a day after his divorce. As he did not have the required length, he was rejected but despite his poor health and frail appearance, he did pass the physical test of the army. Instead of entering service though, he decided to travel to the United Kingdom once more to report on the build up of American troops over there. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, America had entered the war on Allied side. Ernie stayed in England for four months visiting numerous army compounds where American troops awaited their baptism of fire at the front. His columns in which he described the life of the soldiers and their relationship with the British were read greedily by the parents of the boys sent overseas and other staying behind on the home front. Consequently, his bosses permitted Pyle to stay another six months.

The Allied invasion in North-Africa

Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of French North-Africa was launched November 8, 1942. It was the first military operation with American participation. Two days later, Ernie Pyle arrived in the region with a convoy but it took until November 23 before he went ashore himself in the Algerian port of Oran. Prior to his arrival, the city had been taken from the Vichy-French by American troops and the front had shifted east towards Tunisia which had been invaded by the German army. Pyle decided not to follow the troops yet but to stay in Oran for the time being. He wrote a critical column about the inexperienced and poorly equipped American army needing months to defeat the Germans and about the weak policy towards the defeated French collaborators. Nevertheless the critical article passed the censorship, creating political turmoil in the United States.

At the American air base at Biskra, in the desert some 248 miles from Algiers, Ernie witnessed a German bombardment, three hours after his arrival in January 1943. Just like he let himself be inspired by the stories of pilots during his period as aviation correspondent, so were the experiences of members of the air force the main ingredients of his columns again. He left strategical and political evaluation to his colleagues. The death of soldiers or in particular the way they survived were often the main theme in his articles. For instance he wrote about how a pilot was extricated from his B-17 Flying Fortress after he had made a crash landing on the base and was killed in the process. And about the amazing return of another B-17 with its complete crew which had already been assumed lost. In his articles he let his own experience and emotions emerge clearly, just like he had always done in his pre war columns.

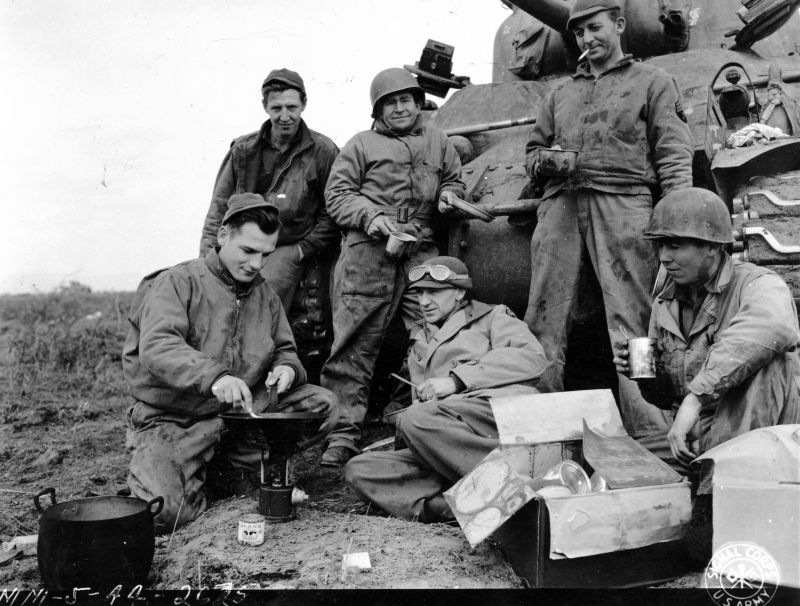

After his stay on the air base, Ernie joined troops of the U.S. 2nd Corps in Central Tunisia in January 1943. Although he was no soldier himself (correspondents were not allowed to carry arms) he was nonetheless readily accepted by the men who considered him one of the boys. He enjoyed their respect not only because he showed interest in the common soldier and could start a conversation easily, but also because he demanded no preferential treatment and lived like they lived. Pyle fed himself from the same field kitchen, dug foxholes and slept on the ground. This rough life did him a lot of good and yielded sufficient inspiration for his columns. "Ernie is there where the assault troops are," Lee Miller stated, "sleeping on the ground fully dressed, freezing to death, a month without a bath and so on. In my opinion, his stories on the life of our troops are great material for newspapers."

The uncomplicated life of the men and the excitement of war appealed to Ernie but he did not ignore the less romantic aspects. The homesickness, the endless hurry-up-and-wait, the absence of women and the fear of what was to come were subjects he wrote about as well. Deep inside he hated war and he would gradually express this in his columns more and more. He had his first negative experience in February 1943 during the battle for the Kasserine Pass in the Atlas mountains. The Afrikakorps commanded by Feldmarschall Erwin Rommel (Bio Rommel) penetrated the American lines, inflicting heavy losses – in human and material sense - on the Americans. As he would continue doing, in his columns Pyle took the part of the front soldier who had nothing to be blamed for, in his opinion. February 24, the Pass was back in Allied hands. After the Kasserine disaster, Ernie stayed in Algiers for a short while and then returned to the front. Meanwhile, on March 10, 1943, he remarried Jerry by proxy. She had spent some time with the nuns which had been good for her.

During the Allied spring campaign in Tunisia that was launched on April 22, 1943, ending in the Allied victory in North-Africa on May 13, Pyle went along with the American 1st Infantry Division for a few days, which had their work cut out for them during the advance on Bizerte on the northern coast of Tunisia. The bare fortified hills had to be taken from the Germans one by one. Ernie was impressed by the riflemen, normal boys who had evolved into battle-hardened warriors within a short time. In a column he called them "the mud-rain-frost-and-wind-boys..that wars can’t be won without". While most news bulletins focused on commanders and individuals mainly who had performed heroic deeds, Pyle evolved into the advocate of the "god-damned infantry," the common riflemen he considered underdogs and he wanted to give them the hero status they deserved.

Back in Algeria it must have become clear to Pyle his reputation had gone ahead of him. Readers considered him a personal friend and sent him loads of packages containing cigarettes, soap and sweets to share with the troops. Many worried parents sent him letters asking him to be on the lookout for their son, while parents of boys who had been killed sought solace with him. Pyle received so much mail he could not respond to all of it individually but in two columns he thanked his readers dearly for their letters and packages. Meanwhile, Time magazine had named him "America’s most read war correspondent." In November 1942, his columns appeared in 42 newspapers; in April 1943 this had risen to 122 with a sale of in total 9 million with the actual number of readers being even higher. Publishers of books and even Hollywood showed interest in his work so he didn’t have to worry about his finances anymore. During the war he would invest a large part of his income in war bonds and share it with friends and family.

Definitielijst

- Flying Fortress

- Nickname for the Boeing B-17 heavy bomber, because of its heavy defensive armament.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- strategical

- Multiple meanings. Used by the Americans to indicate air force units that had bombers.

Images

St Paul’s Cathedral remains undamaged during the bombardment of December 29,1940. Pyle reported on this event. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

St Paul’s Cathedral remains undamaged during the bombardment of December 29,1940. Pyle reported on this event. Source: Wikimedia Commons. American troops aboard a landingcraft heading for the beach near Oran in Algeria, where Ernie Pyle would go ashore too. Source: Imperial War Museums.

American troops aboard a landingcraft heading for the beach near Oran in Algeria, where Ernie Pyle would go ashore too. Source: Imperial War Museums.At the European front, 1943 to 1944

Campaign in Italy

The hectic city life in Algiers, including all social commitments and the large interest shown to him, soon became too much for Ernie. He sought refuge in an American army compound in Zeralda, some 12.5 miles from the Algerian capital.

It did not take long for the Allies to launch a new operation aimed at Sicily. The Italian island in the Mediterranean was to serve as a springboard for the invasion of mainland Italy, ruled by Hitler’s ally, Benito Mussolini (Bio Mussolini). The invasion, code named Operation Husky was launched on July 10, 1943. A few days before, Ernie had been transferred by the army from Algiers to Bizerte where he boarded the American flagship, U.S.S. Biscayne. Aboard this vessel he witnessed the departure of the assault fleet and the landing on Sicily. One and a half week later, he was to disembark himself.

Once ashore, Pyle followed Lieutenant-general Patton’s U.S. 7th Army in the direction of Palermo and its main objective Messina. During his stay on Sicily, the journalist was admitted to a field hospital of the 45th Infantry Division for a week. The diagnosis read "battlefield fever"; caused by "too much dust, bad food, exhaustion and the unwitting mental stress everybody in the front line suffers from," according to the physicians. After having recuperated sufficiently, he advanced together with troops of the U.S. 2nd Corps, witnessing fierce battles in the mountainous area on central Sicily. When he arrived in Messina in the middle of August, the battle was over and the entire island in Allied hands. Ernie had been deeply impressed by the fighting on Sicily. He saw more dead soldiers than in North-Africa. In the army hospital he witnessed severely maimed soldiers being brought in. In his columns he praised the good work of doctors and nurses and he gave solace to the home front that in any case, the victims were in good hands with a fair chance of recovery.

During his stay on Sicily, Ernie was also increasingly confronted with shell shock. Soldiers were totally beaten up mentally by the continuous violence of war. It was also during this time that George Patton (Bio Patton) had called two soldiers cowards and physically assaulted them as they suffered from shell shock. Ernie is said to have hated Patton. "Patton’s name calling, his showmanship and total neglect of human dignity were the exact opposite of Ernie’s docile nature, "a friend of his stated. In Ernie’s columns, Patton was not mentioned even once. Other than Patton, the sensitive journalist understood what soldiers suffering from shell shock had to go through. It became increasingly harder for him to be in a war zone. What he had experienced as an adventure initially was becoming an ordeal for him. He began to suffer from exhaustion, intestinal problems and depressions. "On particularly sad days, it is almost impossible for me to believe that anything deserves such mass slaughter and misery," he wrote in a letter to Jerry.

After having been overseas for 128 days, it was time for Pyle to return home. He arrived in New York September 7, 1943. Meanwhile, 149 newspapers printed his columns and modest Pyle had grown into a national celebrity. Journalists hunted him down for quotes and he was showered with invitations for public appearances and interviews. He retreated to Albuquerque for four weeks as Jerry was not doing well again. She had gone back to drinking and was admitted to hospital for a few days because of alcohol poisoning. During Ernie’s stay in the U.S., his book about his time in North-Africa: "Here is your war" was published on October 28. The book was quickly sold out and the New York Times called it "an important, deeply humane portrait of the American soldier in action." It was to be made into a movie entitled "The Story of G.I. Joe" by order of the department of public relations of the armed forces. The movie was released two months after Ernie’s death in 1945.

November 9, 1943, Ernie met one of his best known readers, the president’s wife Eleanor Roosevelt. The First Lady had invited him to tea in the White House. As columnist and mother of four sons serving in the army, she was highly interested in Pyle’s work. She suggested to write his next columns from the Pacific and report on the American struggle against Japan. Pyle however returned to "his boys" in Europe the same year where the battle had moved to the Italian mainland. With the city of Naples as starting point, he followed the advance of the U.S. 5th Army through Italy. The Italians had surrendered as early as September 8, 1943 but the German army had invaded the country from the north and put up a fierce resistance in the often mountainous terrain on the route of the Allied advance. It would take until May 2, 1945 before the battle for Italy came to an end.

Ernie’s most famous column, entitled "The death of Captain Waskow," was written on January 10, 1944. The column described the death of Captain Henry T. Waskow, company commander of the 36th Infantry Division. He was killed in action on December 14, 1943 during the fighting in mountainous terrain some 43.5 miles northwest of Naples. A few days later his body and those of other dead soldiers, were retrieved on the back of a donkey. Ernie described how the men mourned the death of their beloved commander. The moving article was printed all over the entire front page of the Washington Daily News. It was read on radio and taken over by numerous papers and magazines. It was also reprinted for the promotion of war bonds. Another column, written in Italy by Ernie, advocated the introduction of "fight pay," comparable to "flight pay" which was already habitual for airmen and discussed in Congress. It resulted in a bill, also called the Ernie Pyle Bill which provided an additional pay of 50% for soldiers on active duty.

Pyle’s last posting in Italy was the coastal town of Anzio, some 34 miles south of Rome. Allied troops had gone ashore here on January 22, 1944 in an attempt to circumvent the Gustav line. They were surrounded by the German army and it took until June 5 before the Italian capital was liberated. February 25, Pyle came ashore on the invasion beach at Anzio. Although it was hard for him to be in a war zone again, he stayed in the city for four weeks. He narrowly escaped death when on March 17, the Luftwaffe bombed the villa where he and other war correspondents were housed. A 500 lbs bomb landed right next to the building in which Ernie was sleeping on the top floor. His colleagues, who were all in the ground floor, feared the worst but Pyle was also unharmed. A wall had fallen on the bed in which he had been lying seconds before. He was very frightened but carried on as a major Allied operation was about to be launched.

Allied landing in Normandy

In April 1944, Pyle returned to London. The day after he had followed in the footsteps of his example, Kirke Simpson by winning the Pullitzer prize on May 1, 1944, he exchanged the British capital for the country. He paid a visit lasting a few days to an American Tank Destroyer Battalion and a B-26 Bomb Squadron. Because little was happening, Ernie had trouble writing interesting columns. That would change drastically on June 6, 1944, when Allied troops went ashore on the Normandy coast. Pyle did not belong to the chosen 28 journalists who went ashore with the assault troops on the first day, D-Day, but he arrived a day later on Omaha Beach in a Landing Craft Assault (LCA). Meanwhile, the front had shifted a few miles inland but the beach still showed the signs of battle: wrecked war material and the bodies of American soldiers who had been killed.

"I took a walk along the historic coast of Normandy in France," Ernie wrote in a column as if writing an article for a travel guide, "it was a beautiful day to roam about the beach. Men were sleeping on the sand, some of them forever. Men were floating in the water but they did not know they were in the water as they were dead." This veiled, almost poetical way to describe the atrocities of war had become Pyle’s trademark. He omitted the worst horror, knowing he would hurt the feelings of soldiers’ relatives. He always praised the deployment of the military and he offered consolation to the nation in trying times. Moreover, he had to take military censorship into account which demanded a pro American undertone from journalists. For Pyle, such a thing was without saying: speaking evil about American military did not enter his mind. This made him beloved, as became evident from the fact that in the days following D-Day, 90% of the letters to Scripps-Howard contained the question whether Ernie had survived the Allied invasion.

During the remainder of the Normandy campaign, Pyle initially advanced with the 9th Infantry Division during the capture of Cherbourg. Although he had witnessed a lot already, he was overwhelmed by the ferocity of the fighting and the number of deaths in Normandy. "This hedge-to-hedge stuff is a form of warfare we haven’t had to cope with before," he wrote to a friend, "and I have seen more dead Germans than ever in my life; Americans as well but not so many as Germans." He was under enemy fire more than ever and since the bombing in Anzio, he was startled at the sound of any aircraft flying past. His ulcer troubled him again and he had difficulty sleeping. Exhausted physically and mentally, he stayed in the rear area for a short while with a unit that kept busy with repairing weaponry. On July 17, 1944, his portrait appeared on the cover of Time Magazine with the headline "He loves people and hates war."

The blood was thicker than water and Pyle returned to the front troops in the same month. He followed the 4th Infantry Division in Operation Cobra which lasted from July 25 to 31, 1944; its objective breaking out of Normandy. From a seemingly safe distance he watched the Allied bombardment on St. Lô. He felt the explosions reverberate deep inside him. It was a sensation he had never experienced before. Many bombs were released earlier than planned and had caused havoc. Although he came through the bombardment unscathed himself, that did not apply to many soldiers in the surrounding open terrain. No less than 111 men were killed and nearly 500 injured as a result of that friendly fire. Ernie’s verdict on the disastrous blunder was mild. "The embitterment is followed by the sobering thought that the Air Corps is the strong right hand preceding us," he wrote in his column. "Anyone can make a mistake." It was an attitude devoid of criticism, characteristic for reporters during World War Two, which was abandoned by reporters in later wars such as Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan.

But despite his soothing words, the bombing had made an enormous impression on Pyle. He had literally become sick of it and was overcome by depressions. "That bombardment," he told his friend and business representative Miller, "was the most horrible I have ever gone through." He was afraid of losing his mind when he was to endure something like that once more. After he had witnessed the liberation of Paris on August 25, 1944, he decided to return home. "I have been submerged in it for too long," he apologized in a column that meanwhile was read by an estimated 40 million readers. "My soul is out of balance and my mind is shaken. The pain has finally become too severe."

Definitielijst

- D-Day

- The day of the long awaited invasion of western Europe in Normandy, France, 6 June 1944. After a long campaign of deception the allies attacked the coast of Normandy on five beaches to begin their march on Nazi Germany. Often explained as Decision Day, though this is entirely correct. The D stands for Day as generally used in military language. In this case it means an operation beginning on day D at hour H. Hence “Jour J“ in French.

- Destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- Gustav line

- German defensive line in the south of Italy to prevent the advance of the Allies.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Images

In southeast Asia

Pacific Theatre of Operations

After his return to the U.S., he spent a few days in New York, posing for sculptor Jo Davidson who made a bust of him which is now on public display in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington. He hardly got any chance to rest as various newspapers and radio stations tried to lure him with loads of money to come and work for them. Pyle had stronger ties however to his familiar relation with the Scripps-Howard leadership than to large amounts of money and could not be baited. During his stay in the U.S. he received two honorary doctorates, from New Mexico University and from Indiana University where he had studied himself. Initially, all appeared to go well with Jerry but in the period Ernie was back in Albuquerque, she cut her whole body with a knife and a shaving blade and she was subsequently admitted to an asylum.

Jerry’s self-mutilation was probably caused by her fear Ernie would return to the front again. Her fear was not unfounded as after Christmas he began preparing for a new journey. This time he would go to the Pacific Theatre of Operations. He felt duty bound towards the American G.I.’s who were fighting on this front and to whom he had not paid any attention yet. January 21, 1945. he landed on the island of Guam where the headquarters of the American Pacific Fleet was located. Here he was widely recognized as well. During his stay in the region, aboard the light carrier U.S.S. Cabot the navy familiarized him with a life much more comfortable compared to that at the European front. It made him think of a "leisure cruise in peace time." The crew wanted for nothing: pilots were sunbathing, tennis was being played on the flight deck. Steaks and ice cream, movie shows and hot showers competed the luxury life. The biggest enemy was the monotony on board.

During his stay in the Pacific, Ernie visited the island of Saipan as well where the grandson of an aunt was stationed as radio operator in a B-29 bomber. Writing in a cottage on the beach with palm trees and a refreshing breeze, he found it "a paradise." The men here also had an easy life as compared to their colleagues in Europe. There was another side to the coin as well though which Ernie would experience himself after he had landed on the Japanese island of Ie Shima on April 17. As part of the battle for Okinawa, the 77th Infantry Division was to capture the airfield on the island. Ernie was able to go ashore without any problems as the battle was raging farther inland. The next day, fate struck however as he hitched a ride in a jeep with Colonel Joseph Coolidge to find a new location for a command post. After having been suddenly fired upon by the enemy, they jumped into a ditch for cover. As Ernie looked up from there he was hit by a bullet in his left temple, just below the rim of his helmet. The 44-year old war correspondent and national hero was killed instantly.

Demise and remembrance

Ernie Pyle’s body was buried in a field grave on the island. A slip of paper was found among his personal belongings with a column he had written on occasion of the war in Europe being over. Although the German surrender was only three weeks away, the column was not published, Probably because it was gloomier than his readers were used to. He had written:

"Dead men produced in masses – in one country after the other – month after month and year after year. Dead men in winter and dead men in summer. Things you people at home shouldn’t even try to understand. For you at home they are just columns, figures, or a relative who went away and simply didn’t come back. You did not see him lying alongside a dirt road in France, grotesque and bloated. We saw him. Saw them in their thousands. That is the difference."

In the U.S. the news of the demise of the beloved correspondent was received with great sadness. Six days before, President Roosevelt had passed away as well."The nation is in mourning again by Ernie Pyle’s death," Roosevelt’s successor Harry Truman declared. Jerry was not to overcome the loss of her husband and passed away in November 1945 as a result of complications of influenza. Years later, Ernie Pyle was reburied on the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Punchbowl Crater on Hawaii. In April 1983 he was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart, although civilians are not eligible for this decoration which is only meant for military personnel wounded or killed in battle. The house he was born in, was rescued from demolition and relocated to Dana; it is a museum nowadays.

Definitielijst

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Purple Heart

- American military award. Awarded to those who got wounded during war.

Images

Information

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related themes

News

G.I. Stories 1941-1945 wants to bring the story of the American soldier to a larger audience

John J. Capasso runs the Instagram account @g.i.stories41_45, which is also the name of a series of booklets published between 1942 and 1945 by the US Army magazine Stars and Stripes about the Second World War. John also posts clips on YouTube and Facebook under the same name. G.I. Stories is one of the better history accounts and it frequently uploads high-quality content about American soldiers during the Second World War. He has more than 10,000 followers and posts content daily. We’ve emailed him some questions and he was kind enough to answer them.