Youth and early career

Introduction

Arthur Nebe (1894-1945) was a police detective in Berlin and started his Nazi career in 1933 as a member of the Gestapo. Ultimately he rose to chief of the Reichskriminalpolizeiamt, the central office of the German criminal investigation police or Kripo. In the first months of the German invasion of Russia, Nebe was in command of Einsatzgruppe B. The mass murder on the Eastern Front he was involved in, was the prelude to the extermination of Jews in the extermination camps. In addition to his role in the extermination of Jews, Nebe also played a part in the persecution and deportation of Gypsys in Germany. Yet, at the same time, he acted as informer for the German military and conservative opposition. An important role was alloted to him during the attempt and coup of July 20, 1944.

This article is a summary of the book entitled "Het masker van de massamoordenaarr" by the same author.

Youth, World War One and the Weimer period

Arthur Nebe was born November 13, 1894 in Berlin, the son of teacher Adolf Nebe and his wife Bertha Lüder. August 7, 1914, he passed his final exam of the Gymnasium. Meanwhile, World War One had erupted and he reported as a volunteer in the Imperial army. He was promoted to Leutnant on February 20, 1915. From February 23, 1915 he fought at the front until the end of the war, being wounded twice due to gas attacks. On his return from the war, he was a highly decorated war veteran with the EK I and 2 (Iron Cross), the Ehrenkreuz der Frontkämpfer (Medal of Honor for front fighters) and the Verwundetenabzeichen in Schwarz (medal for the injured in black). After the war he remained active in the army as an adjutant.

After the German defeat in 1918, Nebe was honorably discharged from the army on March 30, 1920 and promoted to Oberleutnant a.D (retired). It was difficult for him to find a new existence in a Germany, ravaged by economic and political problems. Just like many other jobless veterans he joined a Freikorps, a paramilitary unit which armed itself against a leftist revolution. It was mainly due to the fact he had no university schooling and was unable to find work anywhere else and not out of vocation that he joined the Berlin police. On April 1, 1920, he entered service as Kriminalkommissar-Anwärter or student detective. His appointment as Kriminalkommissar followed July 1, 1923. August 15 the next year he married Elise Schäffer and daughter Gisella was born January 26, 1926.

In order to boost his career, Nebe took some semesters in medicine and economics at the university of Berlin. He made a quick career in the various departments of the criminal investigation department. He rose to leader of the narcotics department. In that capacity he wrote a publication in 1929 about the causes of drug use. In addition, he contributed to the magazine of the department, the Kriminalistischen Monatsheften. On April 1, 1931, Nebe was appointed chief of the department of robbery. In the 20s, he kept a low profile ideologically speaking and he was hardly active in the political sphere although his sympathies lay with rightist nationalism and not with his employer, the democratic Prussian government in which the social democratic party played an influential role.

Regarding his previous membership of a Freikorps and his aversion towards leftist political parties, Nebe felt attracted to the Nazi party and he joined it on July 1, 1931. November 5, 1931 he also enrolled in the SA where he would rise to Sturmhauptführer in 1936. As police personnel was prohibited from joining national socialist organizations, Nebe must have joined in secret. As early as 1933 Nebe and some of his colleagues within the Berlin police were already working towards a seizure of power by the Nazis. In 1932 they founded a trade union for Nazi police personnel. the Nationalsozialistische Beamten-Arbeitsgemeinschaft (N.S.B.A.G). Nebe and other members of the N.S.B.A.G. provided N.S.D.A.P. politician Kurt Daluege with information on the Kriminalpolizei and its leaders who could be useful once the Nazis were in power. Being a member of the Reichstag (German parliament) Daluege occupied himself with police issues and would be in charge of the Ordnungspolizei, the uniformed police, during the period of the Third Reich from 1936 to 1945.

Definitielijst

- Freikorps

- German paramilitary units established directly after the Great War by former front soldiers. These groups were often named after their commander. Freikorps formed the basis of the eventual SA or Sturmabteilung.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Iron Cross

- English translation of the German decoration Eisernes Kreuz.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Kripo

- Kriminalpolizei. Criminal investigation agency. Ordinary civilian police of Nazi Germany.

- Medal of Honor

- United States of America’s highest military honour. Awarded for awarded for personal acts of valor above and beyond the call of duty.

- nationalism

- The pursuit of a people to become politically independence or securing such independence.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- revolution

- Usually sudden and violent reversal of existing (political) the political set-up and situations.

Images

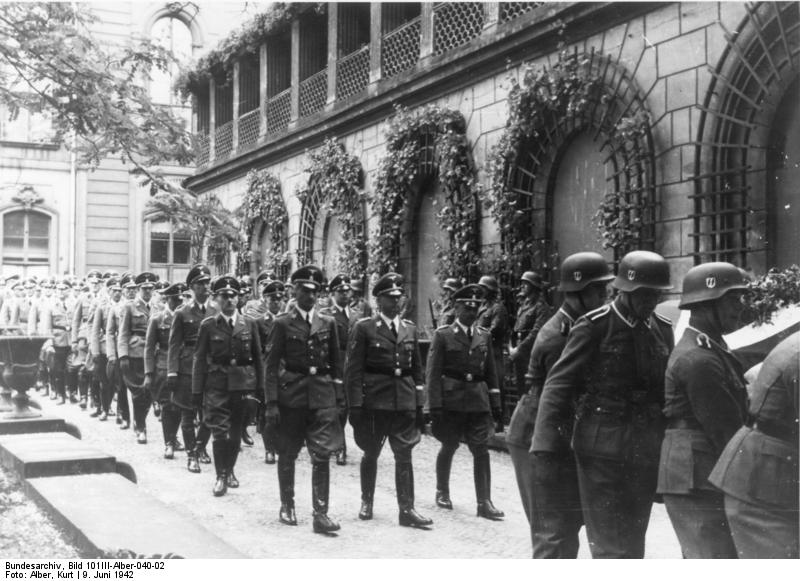

Chief of the Reichskriminalpolizeiamt.

Career in the Gestapo and the Kriminalpolizei

After Adolf Hitler had been appointed chancellor on January 30, 1933, Arthur Nebe’s career soared. He was called for by Kurt Daluege who meanwhile was engaged in police issues within the Prussian Department of Foreign Affairs and promoted to Kriminalrat (a police rank comparable to a captain in the army) on April 1, 1933. Nebe was transferred from the forensic department to the Geheime Staatspolizeiamt, the Prussian political police which formed the foundation of the Gestapo. Within the Gestapo, Nebe was appointed chief of the department responsible for investigation into political movements, including Communism, anarchism and the social democratic party. His promotion to Regierungs- und Kriminalrat followed on August 29, 1933.

Within the Gestapo, Nebe acquainted Hans Bernd Gisevius. Between the two, a friendship emerged based on their mutual aversion towards Rudolf Diels, the incumbent chief of the Gestapo. After a temporary discharge in 1933, Diels was permanently discharged in April 1934. After the war, Gisevius said about their unease about Diels that Nebe felt shocked by the murders of political opponents that Diels, with permission by Hermann Göring had the Gestapo carry out. According to Gisevius, the political assassinations between June 30 and July 2, 1934, better known as the Night of the Long Knives, were decisive. Nebe's criticism of the events in 1933 and 1934 probably formed the early base for his later involvement in the German resistance against Hitler but it did not prevent him from holding a top position within the Nazi leadership in subsequent years.

After Diels’ discharge and the take over of the Gestapo by SS leader Heinrich Himmler and his crony Reinhard Heydrich Nebe also took an important step in his career. Once again, he was called for by Daluege at the Prussian Department of Internal Affairs where he was told the leadership of the Prussian Landeskriminalamt, the central investigation department with its office in Berlin, was entrusted to him as per January 1, 1935. Formally, Heydrich was the head of the Kriminalamt and Nebe his deputy but daily management lay in Nebe’s hands. On April 1, 1935, he was promoted to Oberregierungs- und Kriminalrat.

In August 1936 Nebe was appointed chief of the Amt Kriminalpolizei, the department in Heydrich’s Sicherheitshauptamt responsible for criminal investigation. In addition, the Prussian Landeskriminalamt, headed by him, was given overall control of all forensic departments in the other federal states on September 20, 1936, making him the most powerful crime fighter in Germany. It would not take long for someone of his status to be incorporated in the SS. He entered service on December 2, 1936 in the rank of SS-Sturmbannführer. In July 1937, his position was further enhanced when the Prussian Landeskriminalamt was converted to a state organization. From then on, the organization became known as Reichskriminalpolizeiamt and Nebe could call himself Reichskriminaldirektor.

Led by Nebe, the Kripo was expanded further and became more professional. It was no longer a conventional forensic agency but just like the Gestapo, an organization based on ideology embedded in the Nazi machinery of terror. Tens of thousands fell victim to the joint efforts of the Gestapo and the Kripo. Not only those who had previously been sentenced for a crime but likewise, the homeless, gypsies, drunks and homosexuals were put in preventive custody as they, according to Nazi theory were suspected of having criminal leanings. Without intervention by a judge they sometimes were interned to be re-educated in a concentration camp for years where many of them died.

Blomberg – Fritsch affair and early resistance contacts

Despite the fact Arthur Nebe had risen to a high ranking position in Germany, he remained a critic of the Nazi regime. According to Gisevius, the Blomberg – Fritsch affair of 1938 put Nebe’s belief in Nazism further to the test. Both Generalfeldmarschall Werner von Blomberg, Reichsminister of War and Generaloberst Werner von Fritsch were brought down, the first because of a marriage to a prostitute, the latter because of a phony charge of having frequented a lover boy in Berlin. After both men had been dishonorably discharged Hitler replaced the Department of War by the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW, Supreme command of armed forces), naming himself commander-in-chief. He was able to do this without opposition by the army command. According to Gisevius, Nebe was enraged about the complacency of the army leadership. His own role in this affair is a dual one though: on the one hand he criticized Hitler’s increasing influence on the armed forces, on the other hand, it was his Kripo that provided the pornographic pictures of Blomberg’s wife as evidence against the general.

After Hitler had shaped the Wehrmacht to his liking, he was able to achieve his territorial goals. Following the re-occupation of the Rheinland on March 7, 1936 and the annexation of Austria on March 12, 1938, Czechoslovakia was next on Hitler’s agenda. There were high ranking military in the Wehrmacht though who feared that an invasion of Czechoslovakia would trigger a war against France and the United Kingdom. They were of the opinion, Germany was not yet ready for a new war and started making plans for a coup against Hitler together with a few conservative politicians and civilians.

Gisevius took part in the conspiracy too. He was charged with "preparing all measures required for a coup regarding the police." Nebe provided him with information as to where armed units of the SS were billeted. The coup would not take place as the Treaty of Munich, which provided for a non-violent solution of the crisis, took away the most important motive for the conspirators. Contacts between the military and civilian resistance decreased or were cut altogether and the organization fell apart. A few years later though, plans for a coup were drafted once again by mainly the same men.

Definitielijst

- Communism

- Political ideology originating from the work of Karl Marx “Das Kapital” written in 1848 as a reaction to the so-called class struggle between the proletariat (labourers) and the bourgeoisie. According to Marx the proletariat would take over power from the well-to-do classes though a revolution. The communist movement aspires an ideal situation where the means of production and the means of consumption are common property of all citizens. This should end poverty and inequality (communis = common).

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Gestapo

- “Geheime Staatspolizei”. Secret state police, the secret police in the Third Reich.

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Kripo

- Kriminalpolizei. Criminal investigation agency. Ordinary civilian police of Nazi Germany.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Nazism

- Abbreviation of national socialism.

- Night of the Long Knives

- Night of 30 June to 1 July 1933 during which Hitler killed many of the demanding leaders of the SA, including Ernst Röhm.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Second World War

Campaign in Poland and other activities in the fall of 1939

Instead of resisting Hitler’s plans for war, Arthur Nebe contributed to the invasion of Poland in September 1939. In order to justify the invasion, the SS and the Abwehr launched simulated attacks by Poles on German targets. To convince the world of the Polish aggression, an investigation committee headed by Arthur Nebe and Gestapo chief Heinrich Müller recorded the events of these "Polish" attacks. Nebe was also in charge of an investigation into the mass murder at Bydgoszcz (Bromberg in German) where Polish soldiers and civilians had allegedly caused a blood bath among the ethic German population. Although Nebe concluded the number of victims amounted to a few thousand, Hitler ordered this number to be set at 58,000. In the fall of 1939, Nebe was active in the Polish capital for three weeks. He was sent there to temporarily replace SS-Brigadeführer Lothar Beutel – who had fallen into disgrace – as the leader of Einsatzgruppe IV and commander of the Sipo and SD in Warsaw.

In the fall of 1939, Nebe occupied himself with the planned removal of some 30,000 Gypsies from Germany, considered racially inferior and anti social by the Nazis. Due to logistic problems, their deportation had to be postponed but that did not save them. Just like the Jews they would fall victim to a program of systematic extermination from 1941 onwards. In co-operation with the Kriminalpolizei, which saw to their registration and arrest, an estimated 15,000 German Gypsies were murdered by the Nazis; mainly in the extermination camps.

A few months after the outbreak of war, Nebe had to make an unexpected trip to Munich. On November 8, 1939 a failed attempt on Hitler’s life had been made in the Bürgerbraukeller. Nebe was in charge of the forensic investigation at the crime scene while the Gestapo was busily tracking down the culprit. The same day, 36 year old Georg Eiser was arrested. As late as the night of November 13 to 14, Eiser confessed in the office of the Munich Gestapo in the presence of Nebe. Eiser told them how he had prepared and carried out the attempt on his own. On April 9, 1945, after having spent years in detention, he was murdered in Dachau concentration camp by a shot in the neck, ordered by Hitler.

Commander of Einsatzgruppe B

As per January 1, 1941, Nebe was promoted to SS-Brigadeführer und Generalmajor der Polizei. From June 22, 1941, during the German invasion of the Soviet Union, he was in charge of Einsatzgruppe B. In the first 6 to 8 weeks of the invasion, the 4 Einsatzgruppen were mainly engaged in the execution of Communist officials, "alleged" partisans and adult Jewish males but from August onwards, Jewish women and children fell victim as well. Nebe’s unit operated in Byelorussia and in the region of Smolensk and was subordinate to Heeresgruppe Mitte. During his stay, he kept in touch with Oberstleutnant Henning von Tresckow the chief of staff of Heeresgruppe Mitte and his adjutant Leutnant Fabian Von Schlabrendorff. Both men were members of the military resistance and would be involved in various failed attempts on Hitler.

Nebe’s Einsatzgruppe left Germany from Pretzsch and arrived in Posen, Poland on June 23, 1941. A day later they continued towards Warsaw. July 5, Nebe and his staff reached Minsk where he established his HQ for a month. Meanwhile, mass executions were carried out on various sites. August 5, Nebe’s HQ was relocated to Smolensk. From there, Nebe was in charge of Vorkommando Moskau which was tasked with clearing Moscow and surroundings from Jews. The unit never reached Moscow however due to the failure of Operation Typhoon, the offensive launched against the Soviet capital by the German Wehrmacht.

August 14, 1941, Heinrich Himmler paid a visit to Minsk. The next day, the SS chief was present at an execution Nebe’s men carried out on his request. The executions took place in a forest north of Minsk. The victims were alleged partisans and Jews, including two women. After the war, witnesses testified Himmler had been nervous during the execution. He would even have panicked when the women did not die from the first shot. As he had now witnessed a murder action himself, he was worried abut the consequences these executions had on his men. Therefore he ordered Nebe to find a method of killing which would be less strenuous mentally for the executioners.

Along with Dr. Albert Widmann, a chemist from the Kriminaltechnisches Institut, Nebe carried out experiments with various methods of killing in September 1941. Mental patients were used a guinea pigs. A first test with explosives in a forest near Minsk proved to be unsuccessful, among other things because the disposal of the remains of the victims took too long. A second experiment in a psychiatric ward in Mahiljow (or Mogilev) was successful in the opinion of Nebe and Widmann. The victims were locked into a small chamber and subsequently gassed with the exhaust fumes of two trucks, fed into the chamber through a hose. The use of exhaust gasses was less strenuous mentally for the executioners and much more practical because trucks and rooms suitable for gassing were available almost anywhere.

At the time the Wehrmacht suffered heavy losses during Operation Typhoon, Nebe was no longer working in the Soviet Union: at the end of October 1941 he had returned to Berlin. On November 14, 1941 Berlin received a report which stated that up to that date, the number of recorded executions by Einsatzgruppe B stood at 45,467, most of those carried out during the 4 months Nebe was in command. After the war, his friends of the resistance tried to play down Nebe’s activities during the war. According to Gisevius, the number of victims was not correct: Nebe would habitually have exaggerated the number of executions by adding a zero to them. The actual number can never be ascertained but in general, historians assume the numbers reported to Berlin were actually correct.

Back in Berlin and the Great Escape

The four-month practical deployment in the Soviet Union was advantageous to Nebe’s career. November 9, 1941 Hitler promoted him to SS-Gruppenführer und Generalleutnant der Polizei. It appears from various sources however that Nebe’s work in the Soviet Union had done his mental health no good. His weak mental condition may well have been caused by the intricate split he was in: on the one hand he was the loyal servant of the Nazi regime, on the other hand he sympathized with the German resistance against that very same regime. Nebe’s resistance activities in the period between his return from the Soviet Union and the weeks prior to the attempt of July 20, 1944, consisted mainly of passing information to the resistance. During the week, he was present along with other heads of departments of the RSHA at the daily lunch meeting at Gestapo HQ on Prinz Albrechtstraße 8, initially chaired by Reinhard Heydrich and subsequently by his successor Ernst Kaltenbrunner. At table with the staff of the RSHA, Nebe gathered useful information which he passed on to his contacts in the resistance. There is no evidence showing that this information has been of decisive importance for the plans of the coup.

Following up on an advice from Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Nebe had himself operated upon in Vienna for the Basedow syndrome, an auto-immune disorder typified by hyper action of the thyroid gland. The operation went well and during his recuperation, Nebe established his temporary office in the health resort in Semmering in Austria. On his return to Berlin, Nebe maintained an unhealthy way of life. According to Bernd Wehner he made long days: while all of his associates had already left the building, Nebe was still at his desk doing paper work and smoking lots of cigarettes. In order to stay awake, he used pervitin, an amphetamine which today is known as methamphetamine or crystal meth.

The last big police case Nebe was involved in unfolded in the spring of 1944 and has become known as the Great Escape. In the night of March 24 to 25, 1944, 76 R.A.F. officers managed to escape from Stalag Luft III in Sagan in Lower-Silesia. The prisoners had escaped through a tunnel running beyond the perimeter of the camp. As soon as their escape was discovered, the German authorities ordered a Großfahndung (nation wide search). It took just a few days for the Gestapo and the Kripo to arrest all but three officers. Meanwhile, Hitler had ordered half of the escapees to be executed by the Gestapo in reprisal.

On a suggestion by Himmler, Nebe was tasked with selecting the names of the men to be executed. Max Wielen, chief of the Kripo in Breslau, testified before the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg on April 10, 1946, he had the impression Nebe was shocked by the order. He was of the opinion though, the order had to be carried out nonetheless as there could be no protest against an order by the Führer. After Nebe had passed on the names to the Gestapo, 50 of the arrested prisoners were "shot while trying to escape" by the Gestapo between April 6 and 18. Nebe’s role in the affair did not go unnoticed among the Allies and in December 1945, 8 months after his death he was officially still wanted by the British Secret Service.

Definitielijst

- Abwehr

- Term used for the German military intelligence unit during the WW1 and WW2. From 1935 onwards under command of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. The organisation often came into conflict with other secret services such as the SD and the Gestapo. During World War 2 under Canaris frequently a source for conspiracies against the Nazi regime until in 1943 a major conspiracy by a number of prominent members of the Abwehr was discovered and the Abwehr was placed under command of Himmler. After the assassination attempt on Hitler in 1944, Canaris was discharged and the Abwehr was dissolved. The conspirators and Canaris were prosecuted and in 1945 they were executed atc oncentration camp Flossenburg.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Gestapo

- “Geheime Staatspolizei”. Secret state police, the secret police in the Third Reich.

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Kripo

- Kriminalpolizei. Criminal investigation agency. Ordinary civilian police of Nazi Germany.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- RSHA

- Reichssicherheitshauptamt. The central information and security service of the Third Reich.

- Sipo

- ”Sicherheitspolizei”. Combination (since 1936) of the Gestapo and criminal police.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

The Bürgerbräukeller on November 9, 1939, a day after the bombing attempt by Georg Elser. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1972-025-10 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

The Bürgerbräukeller on November 9, 1939, a day after the bombing attempt by Georg Elser. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1972-025-10 / CC-BY-SA 3.0. Himmler discussing the investigation into the bombing attempt of November 8 in Munich on November 27, 1939. F.l.t.r. Franz Josef Huber, Arthur Nebe, Heinrich Himmler, Reinhard Heydrich and Heinrich Müller Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R98680 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

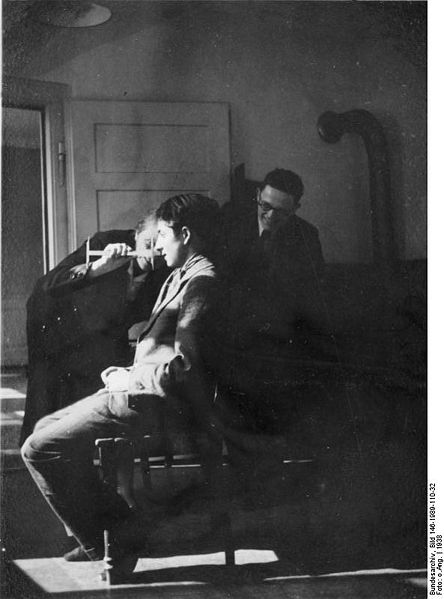

Himmler discussing the investigation into the bombing attempt of November 8 in Munich on November 27, 1939. F.l.t.r. Franz Josef Huber, Arthur Nebe, Heinrich Himmler, Reinhard Heydrich and Heinrich Müller Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R98680 / CC-BY-SA 3.0. Investigators of the Kripo measure the circumference of the head of a young Sinti (Gypsy) in connection with forensic research. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1989-110-32 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

Investigators of the Kripo measure the circumference of the head of a young Sinti (Gypsy) in connection with forensic research. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1989-110-32 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.The July conspiracy and his downfall

Involvement in the coup of July 20, 1944

July 20, 1944, a bomb placed by Oberst Claus Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg exploded in the chart room of Hitler’s HQ in Rastenburg where at that moment the dictator had a meeting with the army leadership. Subsequently, Von Stauffenberg hurried to Berlin where he and other members of the military resistance tried to seize power. Hitler however survived the blast and the coup ended in failure.

Nebe’s role in planning of the attempt and coup of July 20 was secondary only. He may have been informed of the plan but did not belong to the inner circle of conspirators. Since 1940 though, he had spoken about planning a coup and an attempt on Hitler with sympathizers. From that year on, he visited his friends Viktor Schulz and Dr. Albrecht Olbertz on some Fridays at the home of the latter on the Kurfürstendamm in Berlin. Both men were opponents of the Nazi regime and during their meetings with Nebe, later on also attended by police president Wolf Heinrich Graf von Helldorf, they talked about overthrowing the regime. According to Schulz, Nebe had decided as early as 1941 that Hitler should be disposed of.

The meetings in the Olbertz residence were more of a friendly nature, a meeting of equals, than of a conspiracy being hatched. The actual preparations for a coup were made elsewhere, for instance at the home of the Strünck couple on the Badensche Straße in Berlin. Nebe has visited the home of the Strüncks an unknown number of times but he doubted whether the coup that was planned there had any chance of success.

Nebe was to have been allocated an active role on the very day of the coup. The intention was that after Hitler had been killed in the attempt, he and a group of some 15 loyal associates were to arrest high ranking officials of the party and the SS in the meantime, including Joseph Goebbels. Nebe however was convinced from the start the coup was doomed to fail. On July 20, the conspirators frequently urged him to take action but instead of contributing to the coup, he entrenched himself in his office and later in the command bunker of Graf von Helldorf where he just sat waiting. When he was finally sure, Hitler was still alive, he realized it was better to act as if he knew nothing about anything and to return to RSHA Headquarters.

On the run

Initially there was no suspicion against Nebe within the RSHA which was in charge of tracking down those involved in the coup. He managed to keep up the pretence for four days , visiting the daily lunch meetings with Ernst Kaltenbrunner and the other department chiefs. Nebe attended this meeting for the last time on July 24. That day, his comrade in the resistance, Wolf Heinrich Graf von Helldorf was arrested (he would be executed on August 15, 1944). Subsequently, the soil became too hot under Nebe’s feet and in the night of July 24 he joined Gisevius – who had been in hiding with a befriended couple in Berlin since July 20 – and the Strünck couple. The four of them decided to flee from Berlin in Nebe’s Mercedes but as they were unable to find a suitable hiding place they returned to Berlin after a few days and went their separate ways.

In Berlin, Nebe found shelter for a few nights with a befriended female colleague, Adelheid Gobbin. At the end of July or the beginning of August she took him to an estate on Töpchiner Straße 18 in Motzen, a village on the Motzensee in a wooded area southeast of Berlin. The estate, where others in hiding were also housed, was owned by businessman Walter Frick, whose spouse was a childhood friend of Nebe’s wife. Nebe was to remain in hiding at this address until his arrest.

When Nebe did not appear at work on July 25, the Kripo launched a search action. Initially it was assumed he had committed suicide as he had made a depressive impression in the previous months. When he still had not been found at the beginning of August, the suspicion arose he might have had something to do with the coup. Himmler ordered he had to be found, dead or alive and a search warrant was issued. In order not to compromise the Nazi regime at home and abroad, due to the missing of a top notch official, Nebe’s function and rank in the SS were omitted. As a high reward would draw too much attention so this was limited to 50,000 Reichsmark. In November 1944, Himmler was convinced Nebe was a traitor and on November 30, 1944 he was degraded to SS-Mann, the lowest rank of the SS and dishonorably discharged.

Arrest and execution

On January 16, 1945, Gobbin revealed Nebe’s whereabouts under heavy pressure to Gestapo agent Willy Litzenberg. The same night, Nebe was arrested at the Frick estate by a Gestapo team and transferred to Berlin. Towards midnight, he was interrogated for half an hour by Gestapo chief Heinrich Himmler and Kaltenbrunner in Müller’s office in the Gestapo HQ on Prinz Albrechtstraße. After this short interrogation he was taken away to a cell in the building. A day later he was taken out of his cell to be interrogated once again. This would happen frequently until February 3.

February 7, 1945, Nebe was transferred by the SS to a cell in the SS barracks in Buchenwald concentration camp. He was imprisoned there pending his trial before the Volksgerichtshof (People’s Court) in Berlin on March 2. The court considered it established Nebe had been informed of the plans for a coup and that he knew an attempt on Hitler was part of the coup. The court also found him guilty of having made Kripo agents available to the conspirators. He was sentenced to death by hanging. According to a file of Plötzensee prison, Nebe was handed over by the Gestapo on March 2. He probably was executed as early as the next day. Contrary to Von Stauffenberg and other members of the resistance, Nebe is not honored any longer for his contribution to the coup as he had been too deeply involved in the Holocaust and other Nazi crimes.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Gestapo

- “Geheime Staatspolizei”. Secret state police, the secret police in the Third Reich.

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Kripo

- Kriminalpolizei. Criminal investigation agency. Ordinary civilian police of Nazi Germany.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- RSHA

- Reichssicherheitshauptamt. The central information and security service of the Third Reich.

Images

The Gestapo HQ on Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse 8 in Berlin, where Nebe attended the daily lunch conferences with the RSHA leadership. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R97512 / Unknownwikidata:Q4233718 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

The Gestapo HQ on Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse 8 in Berlin, where Nebe attended the daily lunch conferences with the RSHA leadership. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R97512 / Unknownwikidata:Q4233718 / CC-BY-SA 3.0. Article in a German paper about Nebe missing. Note the civilian picture and the remark he had probably fallen victim to a crime. Source: Bundesarchiv.

Article in a German paper about Nebe missing. Note the civilian picture and the remark he had probably fallen victim to a crime. Source: Bundesarchiv. The Volksgerichtshof in Berlin, chaired by Dr. Roland Freisler in session against the perpetrators of the coup of July 20, 1944. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 151-39-21 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

The Volksgerichtshof in Berlin, chaired by Dr. Roland Freisler in session against the perpetrators of the coup of July 20, 1944. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 151-39-21 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.Information

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!