Introduction

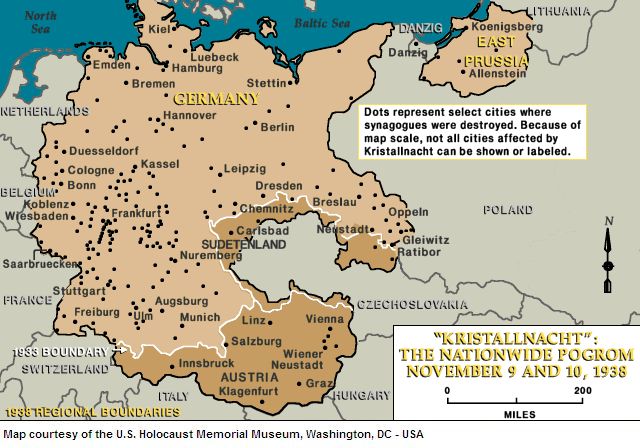

In the night of November 9 to 10, 1938, a large-scale and violent anti-Jewish protest took place in Germany and Austria. Jewish shops and homes were demolished and looted, synagogues were put on fire and individual Jews were mistreated and some even murdered. The protest had evolved into a pogrom. The night would enter the history books as the Kristallnacht (Night of Crystals).

The pogrom will be discussed in this article but special attention will be drawn to cause and consequence for this occurrence; an important turning point in the manner the Jews were treated by the Nazis. Whenever the genesis of the Holocaust – the systematic extermination of an estimated 5.1 to 6 million Jews – is discussed, the Kristallnacht cannot be left unspoken.

In this article, an attempt will be made to show the important role of the Kristallnacht in the history of the Holocaust. In order to achieve this, an image will be drawn of how the Jewish question was dealt with prior to and after the Kristallnacht. Certain measures that were taken in the aftermath of this pogrom form an important foundation for the organized mass murder, the Endösung der Judenfrage (Final solution of the Jewish problem) that was undertaken from 1941 onwards.

Definitielijst

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Kristallnacht

- The night of 9-10 November 1938. Over 250 German synagogues were destroyed. Tens of thousands of Jews were arrested.

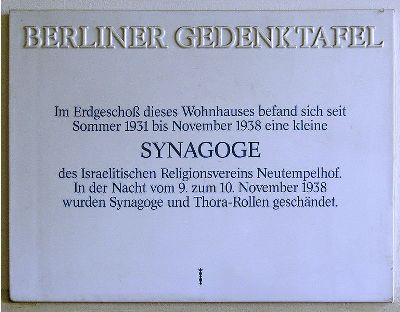

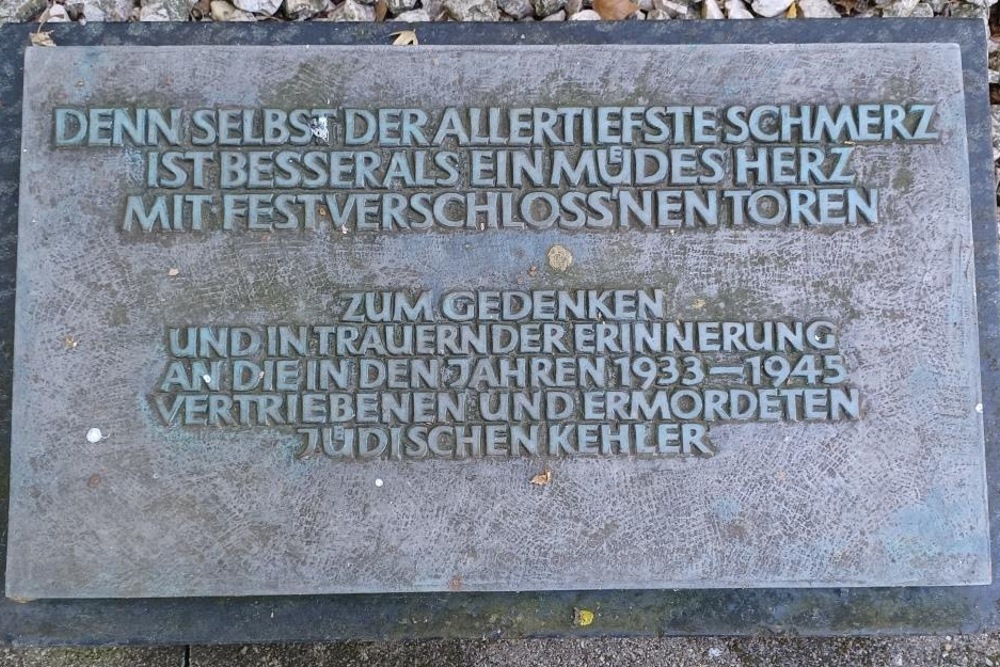

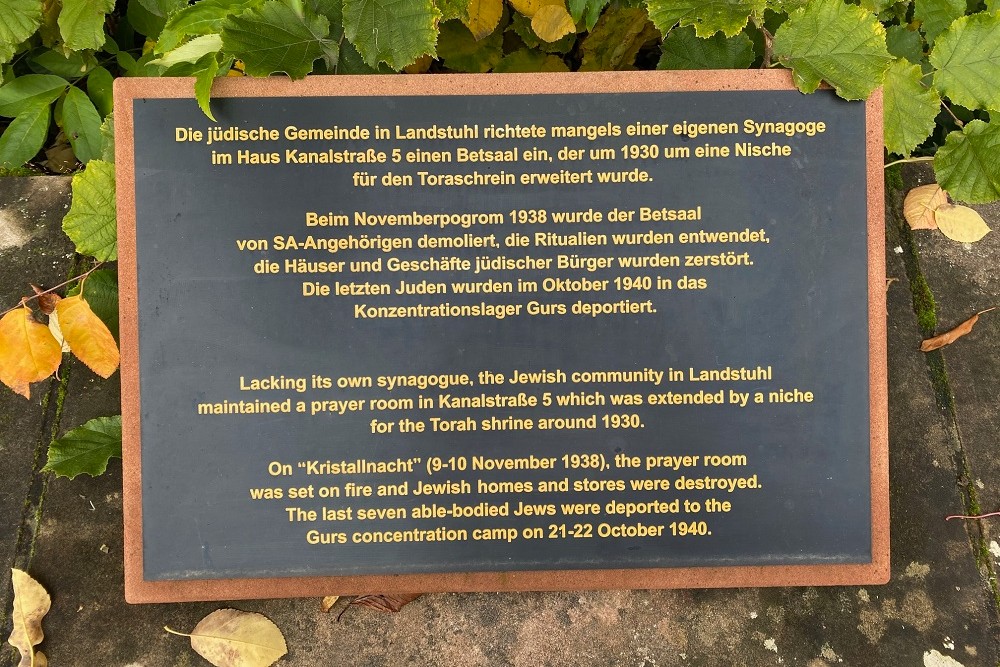

Images

Policy concerning Jews in Germany prior to 1938

From the early start of Hitler’s political career, his views about Jewry were clear. He wrote in his book "Mein Kampf"(my fight) he encountered the "Judenfrage" (Jewish problem) for the first time in Vienna where he had lived for 5 years. Partly influenced by anti-Semitic writings, he increasingly started blaming international Jewry for certain problems in society. He increasingly considered Jews as a destructive people responsible for the German defeat in the First World War and the demise of the former German Empire. As he later wrote in Mein Kampf, "Jewry was the nucleus of the decay of peoples and races and, in a broader sense, the destructor of human culture." He equated Jewry with Bolshevism which he hated and western capitalism. In his opinion, Russian Bolshevism could be seen as: "the attempt made by 20th century Jewry to achieve world dominance." Furthermore, Jews were, according to Hitler, the "masters of capitalism, " their goal being: "to force all free peoples under the straightjacket of international Jewish mega capitalism".

Being an experienced demagogue, Hitler managed to rally a large segment of the German population and many of them swallowed his anti-Semitic rhetoric like candy. In this period of economic malaise, the German population obviously was in need of a scapegoat and the Jews, a group that had continuously suffered from discrimination in the course of history, formed an ideal target. Hitler seized power on January 30, 1933 and from that moment on, the policy concerning Jews was established by the public authorities. The government busied itself issuing legislation aimed at excluding Jews from economic and social life. By means of anti-Jewish propaganda, launched by authorities, anti-Semitism was taken for granted by a steadily increasing segment of the population. Bullying Jews was encouraged and violence against Jews was hardly ever dealt with. In Germany, Jews gradually lost more and more of their rights and ultimately, the would even be deprived of their right to live.

In the months following the seizure of power by the Nazis, Jews were increasingly physically assaulted by members of the Sturmabteiling (SA) and other fanatic Nazi sympathizers. Although the Jews naturally felt unsafe by this violence, it still was unorganized and relatively small scale suppression. On April 1, 1933 the German authorities launched an anti-Jews action on a somewhat larger scale for the first time. In response to an anti-Nazi boycott, initiated by Jewish organizations, that day an anti-Jew boycott was held. The anti-Nazi boycott was organized in reaction to the way the Jews were treated but Joseph Goebbels considered them horror propaganda. During this one-day action, SA men posting in front of Jewish shops tried to prevent customers from entering. Jewish shops were marked with a Star of David and SA men standing in front of the shops held tablets displaying slogans like "Germans! Take note! Do not buy from Jews."

Although the anti-Jewish boycott was to progress peacefully, shop windows were smashed nonetheless and lootings erupted in many places. Jewish shop owners were also maltreated, just like for instance Jewish lawyers and judges who were forcibly expelled from court houses in various cities. In blatant violation of the strict orders from the organizers, shops of foreign Jews were attacked as well. Right from the moment of the announcement, the boycott drew fierce protests abroad. Probably fearing the economic consequences these protests from abroad could cause, it was eventually decided to limit the boycott to just one day instead of unspecified duration. While the official boycott had ended, locally it continued unofficially. The SA also kept up its violence against the Jews but after the top leadership of the SA had been eliminated in the Night of the Long Knives on June 30, 1934, the "brown bear" was tamed and violence in public against Jews occurred on a lesser scale for the time being.

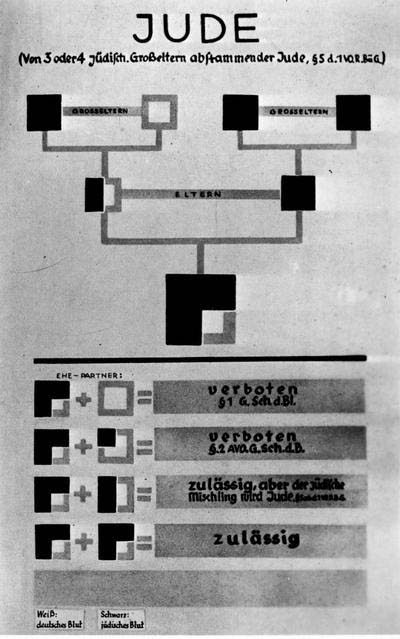

Between 1933 and 1935 the government imposed various limitations on Germans of Jewish descent. From April 29, 1933 for instance, Jews were no longer allowed to work as artists, journalists, movie makers or musicians and on December 31, 1935, the last Jews government officials were fired. The "Nürnberger Rassengesetze" (Nuremberg laws on races), instituted on September 15, 1935 were particularly stigmatizing. The Reichsbürgergesetz and the Gesetz zum Schütze des Deutschen Blutes und der Deutschen Ehre were applicable to the Jews policy. The Reichsbürgergesetz entailed that only Germans and people of related blood were considered Reichsbürger or State citizens and that only they could claim their political rights. Jews were still considered Staatsangehörige (subjects) but were deprived of their political rights. The Gesetz zum Schütze des Deutschen Blutes und der Deutschen Ehre served as a protection of German blood and the German honor. Pursuant to this law, marriages and/or sexual relations between Jews and Germans and those of related blood were prohibited. Moreover, Arian women below the age of 45 were no longer allowed to serve in Jewish homes. Partly on occasion of the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, the Jewish problem was shelved for the time being, In 1936 and 1937, no anti-Jewish laws worth mentioning were issued and the aggression against them also abated. In 1938 however, the policy concerning Jews would become a whole lot more stringent than before.

Definitielijst

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Mein Kampf

- “My Struggle”. Book written by Adolf Hitler, outlining the principles of National Socialism.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Night of the Long Knives

- Night of 30 June to 1 July 1933 during which Hitler killed many of the demanding leaders of the SA, including Ernst Röhm.

- Nuremberg laws

- Laws promulgated by Hitler on the party convention on 15 September 1935. These laws alter alia included regulations about marriage and intercourse between Jews and non-Jews. Jews were deprived of German citizenship. Also known as the racial laws.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

Images

A Jewish shop in Berlin during the boycot of April 1,1933. The sign reads: “Germans, watch out! Do not buy from Jews!" Source: Yad Vashem.

A Jewish shop in Berlin during the boycot of April 1,1933. The sign reads: “Germans, watch out! Do not buy from Jews!" Source: Yad Vashem. Members of the SA in front of a Jewish shop during the anti-Jewish boycot in Berlin. Source: Yad Vashem.

Members of the SA in front of a Jewish shop during the anti-Jewish boycot in Berlin. Source: Yad Vashem.Policy concering Jews in Germany from January to November 1938

In March 1938, Austria was annexed by Germany to the satisfaction of the majority of the Austrian population. In the first weeks following the Anschluß, the Austrian Jews were immediately subjected to various discriminating measures and public violence, just like after the seizure of power by Hitler in Germany. Under the direction of members of the Austrian branch of the N.S.D.A.P., Jews working in theatres, community centers, public libraries and universities were sacked. The offices of the Jewish community and Zionist organizations were shut down on March 18, 1938. All over the country, Jews were arrested and locked up at random. Various Austrian Jews grew so dejected, they saw suicide as the only way out of their misery. The suppression of Jews by the Austrian authority had gone off to a much more vehement start than in Germany after the first months following the seizure of power by the Nazis. As a lot of ground was covered in a relatively short period, the Austrian anti-Jew policy was just as fanatic – or maybe even more – as in Germany.

In 1938 more laws were issued in Germany, aimed at the almost total exclusion of Jews from social and economic life. The first of these discriminating laws was issued on June 25 of that year: from then on, Jewish physicians were no longer allowed to treat non-Jewish patients. These discriminating limitations imposed on Jews were meant to make them leave Germany permanently in ever growing numbers. An increasing number of Jews did not want to leave Germany at all but as appeared from the conference of Evian between July 6 and 15, 1938, they weren’t welcome almost anywhere. The conference was called by U.S. President Roosevelt and was aimed to advance the emigration of German and Austrian Jews. Roosevelt wanted to incite the congregated representatives to raise their immigration quotum but out of the 32 countries present, only the Dominican Republic seemed ready to do so, albeit against an extremely high price. Within the international community there was wide spread aversion against taking in Jewish refugees and this made the situation for German and Austrian Jews even worse.

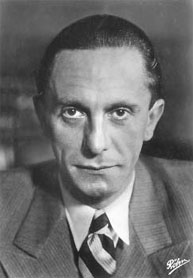

The Nazi plans to expel Jews from the country were thwarted by the outcome of the Evian conference. Tackling the Jewish question became increasingly more violent. Terror and more restrictive laws went hand in hand in the summer of 1938. Indidual Jews were often treated more violently by members of local party branches and synagogues and Jewish cemeteries fell victim to vandalism more often than before. Particularly in Berlin where the fanatical anti-Semite Joseph Goebbels wielded power in his capacity as Gauleiter, the Jews fell victim to all kinds of violent actions. On May 27, a crowd of over 1,000 strong took to the streets in Berlin and destroyed numerous Jewish shops. Not the vandals but the shop owners were arrested and placed in Schützhaft – preventive detention – ostensibly for their own safety. In mid-June this was followed up by a similar action when Jewish shops on the Kurfürstendamm were looted by party officials and plastered with anti-Semitic slogans. Fearing loss of face, these illegal actions were prohibited but this did not prevent similar actions from being executed in cities like Frankfurt and Magdeburg.

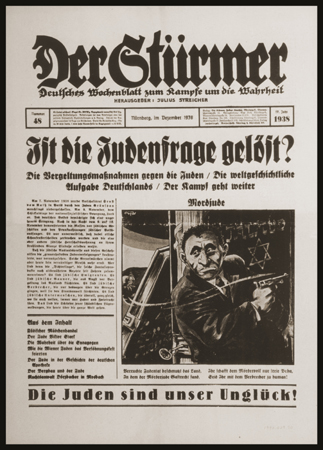

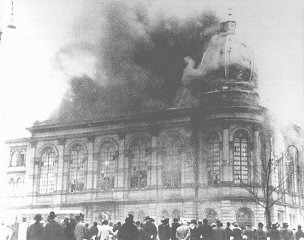

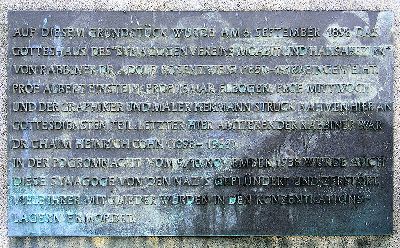

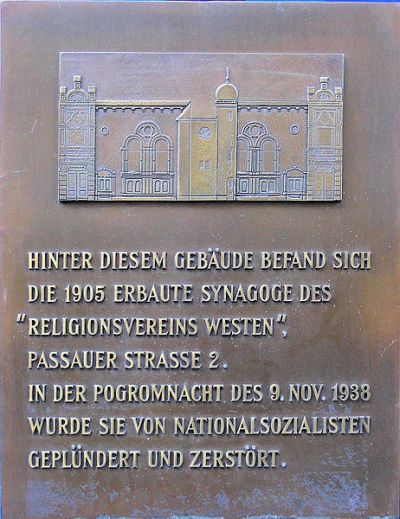

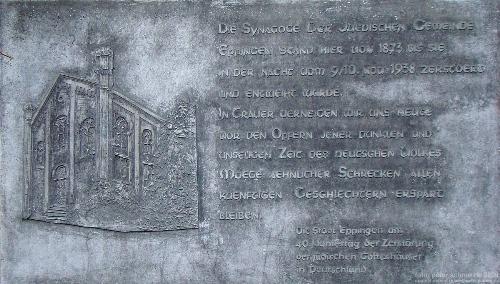

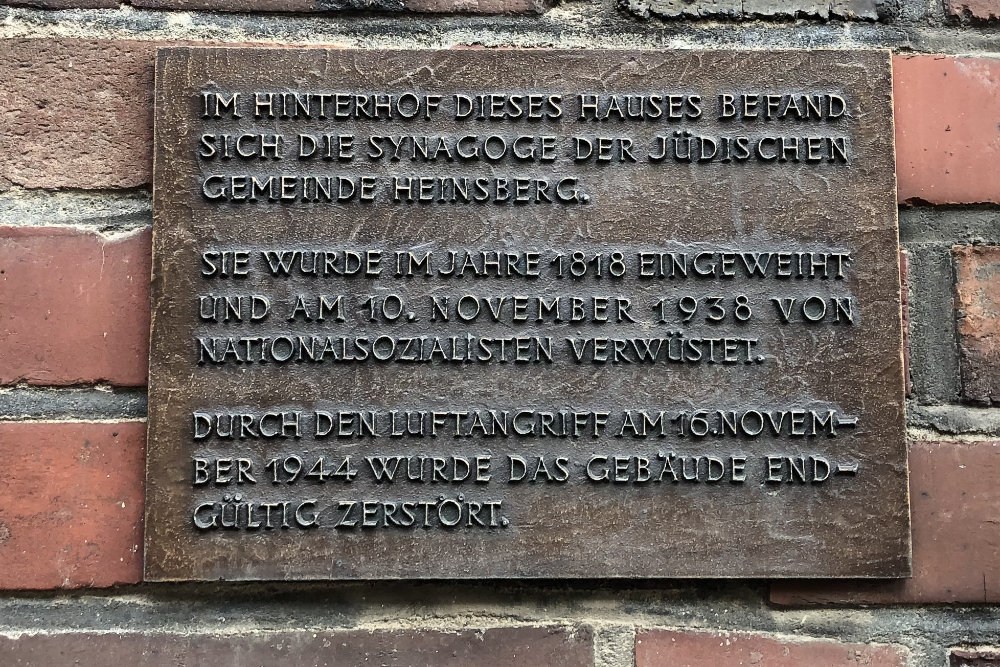

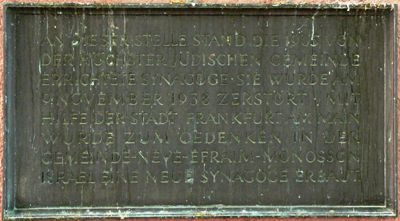

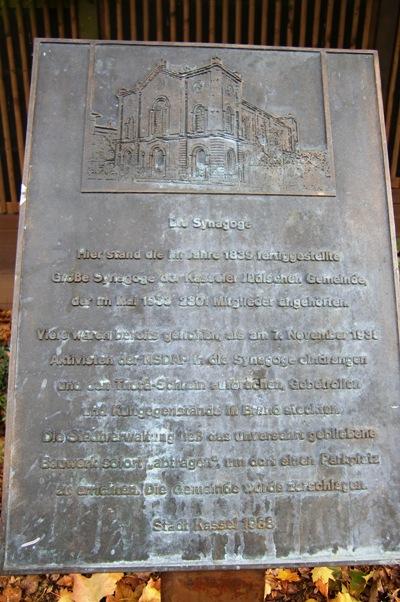

Although illegal destruction of Jewish shops was not approved, the German government did not shy away from demolishing Jewish buildings in a "legal" manner. On June 9, the major synagogue in Munich was destroyed by order of the government because Hitler had been complaining a few days before that this synagogue stood too close to the Deutsche Kunstlerhaus (German house of artists). The official explanation of the demolition was that the building was an obstruction to traffic. Fanatic anti-Semite Julius Streicher, editor of the Nazi magazine "Der Stürmer" emulated Hitler’s action on August 10 by ordering to tear down the synagogue in Nuremberg as it ostensibly defaced the image of the city.

Further stigmatization of Jews was again introduced by legislation: as per August 17, 1938, Jewish males were obliged to add the name "Israel" to their existing name, Jewish women had to do the same, using the name "Sara". Moreover, from October 5 they were obliged to have a "J" stamped on their passport. Meanwhile in Vienna, on August 26, the "Zentralstelle für Jüdische Auswanderung" (Central Jewish emigration office) was founded by Adolf Eichmann. This agency was to implement the emigration and expulsion of Jews from Austria. The Jewish community had to see to it that the number of Jews set by this agency, did actually emigrate. Wealthy Jews were to pay for the emigration of their poorer fellow Jews. Extremely high prices were charged for emigration papers and the possessions of Jewish emigrants were confiscated by this agency. After 1938, similar offices were set up in various countries.

Meanwhile, as of September 27, Jews were no longer allowed to work in court houses and economic exclusion of Jews had come a long way indeed. Early 1933, there were some 50,000 Jewish enterprises in Germany; in the fall of 1938, this number had dropped to 9,000. In the period between spring and fall of 1938, this process was accelerated: in February, some 1,690 enterprises were still owned by Jews: in October, this number had dwindled to only 666. Jewish enterprises were forcibly closed down or taken over by Arian entrepeneurs for bottom prices. Yet, this was still far from sufficient for the Nazi leadership for Hermann Göring, Plenipotentiary for the Four Year Plan announced in the same period: "the Jewish problem must now be solved with all means available because they (the Jews) have to disappear from the economy".

At the end of July, Hitler made a similar announcement but he took it a step further. To Goebbels, he had said: "All Jews must have left Germany within the next 10 years." In the meantime, Jews would have to serve as some sort of security: according to the Nazis, both Bolshevism and capitalism were strongly influenced by international Jewry and whenever war was declared on Germany, the fate of the Jews would be sealed. To what extent this theory has to be taken seriously is hard to determine but the fact remains that in 1938, the Nazis had still not succeeded in driving all Jews out of Germany and its annexed territories. The Jews no longer enjoyed political rights and socially and economically, they were being excluded in growing measure. The final goal: complete elimination of Jews from society was still a long way off and people saw steadily decreasing possibilities as to achieving this goal by the customary methods applied up till then. Instigated by propaganda, followers of Nazism took a steadily growing positive attitude towards violent and radical methods to "expel the biggest enemy of the German people, the Jew." In the Reich, the Jews felt an extremely threatening atmosphere arising. It was like a powder keg with a slow fuse.

Definitielijst

- Four Year Plan

- A German economic plan focussing at all sectors of the economy whereby established production goals had to be achieved in four years time.

- Gauleiter

- Leader and representative of the NSDAP of a Gau.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Nazism

- Abbreviation of national socialism.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- synagogue

- Jewish house of prayer.

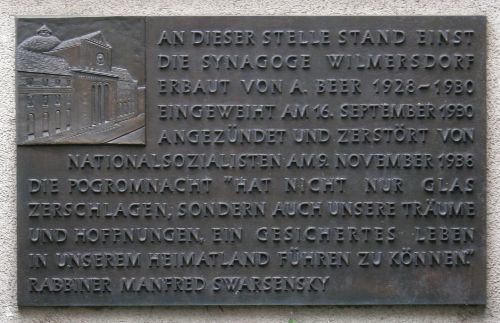

Images

The immediate cause of the Kristallnacht

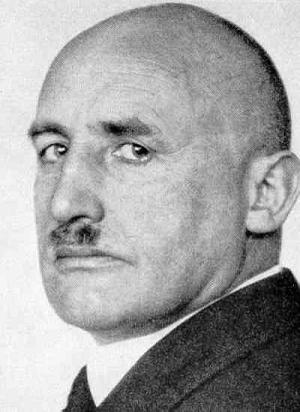

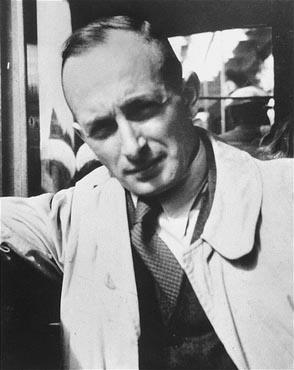

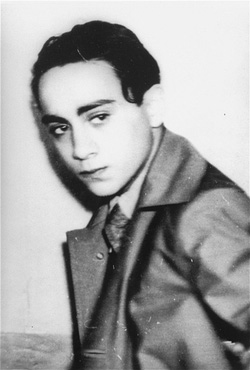

On October 27, 1938 the Nazis started arresting Jews with Polish passports living in Germany. A total of 18,000 Polish Jews were expelled from the country under the pretence that the Polish Minister of Internal Affairs had called on all Poles living abroad to have their passports stamped anew. After they had been expelled however, as from October 29, they were denied entrance to Germany. The Poles had not been informed of the huge number of refugees flooding into the country and they assembled the deported Jews in miserable circumstances in the border town of Zbaszyn out of necessity. When Herschel Grynszpan, a 17-year-old Polish Jew who had fled to France from Germany in 1936, learned his family had also been expelled from Germany, he decided, out of desperation, to kill the German ambassador in France in protest. In the morning of November 7, he entered the German Embassy in Paris and he was received by the third secretary of the embassy, Ernst vom Rath. He decided not to shoot the ambassador but this official: he fired five rounds, three of them missing their target. Vom Rath was rushed to hospital, gravely injured and Grynszpan was arrested by the French police. In 1940, the French authorities handed him over to the Germans. Although Joseph Goebbels wanted to hold a spectacular kangaroo trial in 1942, this has never taken place. Grynszpan’s ultimate fate is unknown but it is hardly likely he survived the war.

2,5 years prior to the attempt on Ernst vom Rath, the leader of the Swiss Nazi party, Wilhelm Gustloff had been murdered by the Jewish medical student David Frankfurter. At that time, reactions of fanatic party followers were quelled but this time, no one took the trouble. Goebbels had seen to it that ferocious attacks against Jews were published in the Nazi press: according to the Nazis, this attempt was not an action by an individual but an element of the Jewish conspiracy. These newspaper articles drew violence because without local party leaders having received orders from higher authority, in some locations synagogues were set on fire in the night of November 8, Jewish possessions destroyed and individual Jews abused. Goebbels wrote about the riots in Hessen: "In Hessen massive anti-Semitic demonstrations. Synagogues are being burned to the ground. If only we could release the wrath of the people now."

In the small German town of Bebra, the police reported about the riots of November 7 and 8 as follows:

- The radio announcement of 7 November 1938 at 10 p.m. regarding the assassination of a German embassy official in Paris by a Jew caused an emotional outburst and incredible rage among the population against the Jews. The rage drove the masses into the streets, breaking the doors and windows of Jewish houses and destroying the interior of the synagogue. During the night, groups assembled and continued the destruction.

One group gathered around 3 a.m. and destroyed the furniture in Jewish homes. Acts of stealing and plunder occurred, if one is to believe the Jewish complaints. In the course of destruction, damage was caused to property that had been Jewish in the past, but was recently transferred into Arian hands. The destruction went on until dawn. In the morning, once it had been established that property had been stolen from the sites that were broken into, the police swung into action. Signs were posted an the Jewish houses forbidding entry, and measures were taken to avoid looting.

On 8 November 1938 at 10 a.m., order was restored. Many were still congregating around Jewish homes, but these gatherings were not of a protest nature. There were curious school children and youngsters. The children and youth caught stealing or destroying property were removed from the scene and their spoils were confiscated. The Jews living in town left in the course of November 8.

To prevent plunder during the coming night, police reinforcement units were positioned and police patrols were intensified. During November 9, 1938, entrances to Jewish homes were sealed off with wooden planks and police presence was reinforced. The damage, not counting the synagogue, is estimated at 80,000 to 100,000 RM. During the anti-Jewish demonstrations, damage was caused only to property; there were no cases of personal injury to Jews.

Source: Yad Vashem Archive 0.51/100

In the evening prior to Kristallnacht, on November 8, Heinrich Himmler delivered an extremely heated speech about Jewry during a meeting with the highest ranking SS men, probably on occasion of the attempt on Von Rath. He said:

- Let no misunderstanding remain: in the next 10 years, we will surely get involved in precarious conflicts. It not only concerns the battle against nations, that will just be pushed to the front by our opponents but it also concerns the ideological struggle against the entire system of Jewry, Free Masonry, Marxism and churches of the world. These forces, of whom the Jews are in my opinion the inspiring pacesetters, the source of all evil, realize all too well that if Germany and Italy are not destroyed, they will be destroyed themselves. That is a straightforward conclusion. In Germany, the Jew cannot hold out. That is a question of years. We will drive them out with increasing and unprecedented ruthlessness. Italy is going the same way and Poland does not want the Jews.

Von Rath succumbed to his injuries in the afternoon of November 9. Goebbels wrote; "Nun aber ist es gar!" (That was the last droplet). Incidentally, the demise of Von Rath coincided with the 15th anniversary of the Bierhalleputsch, the failed coup of 1923 by Hitler and his followers. That night, Nazi big shots and Alte Kämpfer (old warriors) who had been active in the struggle for power prior to 1933, had convened in the old Munich town hall. Notwithstanding the failure of this putsch, commemoration was a yearly highlight for the Nazis. Hitler was present also. On his way to the meeting, Goebbels was informed of the riots in Munich as a result of the attempt on Von Rath. He indicated the police should act light handedly. Hitler had probably also been informed of the attempt on the secretary of the embassy as he had ordered his private physician, Karl Brandt, to lend medical assistance to Von Rath. During the reception, Hitler and Goebbels had a heated discussion but it is not known what had been said. Contrary to habit, Hitler left the meeting earlier than usual; he went to his apartment in Munich. There seemed to be no clue whatsoever he wanted to use the murder of Vom Rath to launch a large scale action against the Jews.

After Hitler had left, Goebbels delivered a short but vicious speech around 10:00 p.m. He said he had some news and he continued:

- Ernst von Rath was a good German, a loyal servant of the Reich who worked in our embassy in Paris to the benefit of our people. Shall I tell you what has happened to him? He was shot while executing his function, unarmed and unsuspecting; he came out to speak to a visitor of the embassy and got two bullets in his body. Now he is dead.

Do I have to tell to you which race that dirty swine belonged to, the swine who committed this heinous crime? A Jew! This night he is in a prison cell in Paris; he claims he has acted on his own, that nobody has made him perform this horrendous act. But we know better, don’t we?

Comrades, we cannot let this attack by international Jewry go unanswered. We must revenge it. Our people must be informed and their answer must be ruthless, determined and expedient! I ask you to listen to me and together we must formulate our answer to Jewish murder and the threat international Jewry poses to our glorious German Empire.

As he wrote himself, his speech was met by rapturous applause and subsequently, everyone ran to the telephone to get the action into high gear. He later wrote in his diary Hitler had given permission for these demonstrations during the discussion he had had with him earlier that evening. He wrote about it:

- I go to the party reception in the old town hall. Very busy. I explain the case to the Führer. He decides: let the demonstration proceed. Withdraw the police. The Jews must feel the wrath of the people for once. Such is the case. Immediately I gave the necessary orders to the police and the party. Then I shall deliver a short speech to the party leadership in this spirit. Rapturous applause. Everyone running to the telephone at once. Now the people will take action.

In the end, neither Hitler nor Goebbels had given an explicit order to party members to hold demonstrations against the Jews throughout the country. The message in Goebbels’ address, the tendency of which had probably been discussed in advance with Hitler, left little doubt: party leaders were given a free hand to execute actions against Jews on their own initiative. Goebbels’ speech was a crystal clear encouragement but carefully formulated as an explicit order for violence might draw protests from abroad. The protest had to look like a spontaneous outburst of anger but the way the Kristallnacht subsequently unfolded proves quite the opposite.

Definitielijst

- Alte Kämpfer

- “Old fighters”. German soldiers with experience on the war front. Sometimes used within the NSDAP for those who had been fighting for the same cause before. Soldiers with battle experience were considered heroes by recruits and the home front, especially towards the end of the war.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Kristallnacht

- The night of 9-10 November 1938. Over 250 German synagogues were destroyed. Tens of thousands of Jews were arrested.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- putsch

- Coup, often involving the use of violence.

- synagogue

- Jewish house of prayer.

- Yad Vashem

- Yad Vashem is Israel’s national Holocaust memorial where in addition to Jewish victims and resistance heroes, also non-Jewish helpers of Jews during the World War 2 are being honoured. Those non-Jewish are called the Righteous Among The Nations. Until the mid 90’s trees were planted for these rescuers. In 1996 a special remembrance garden was established displaying all of the names of the helpers. Every year new names are added.

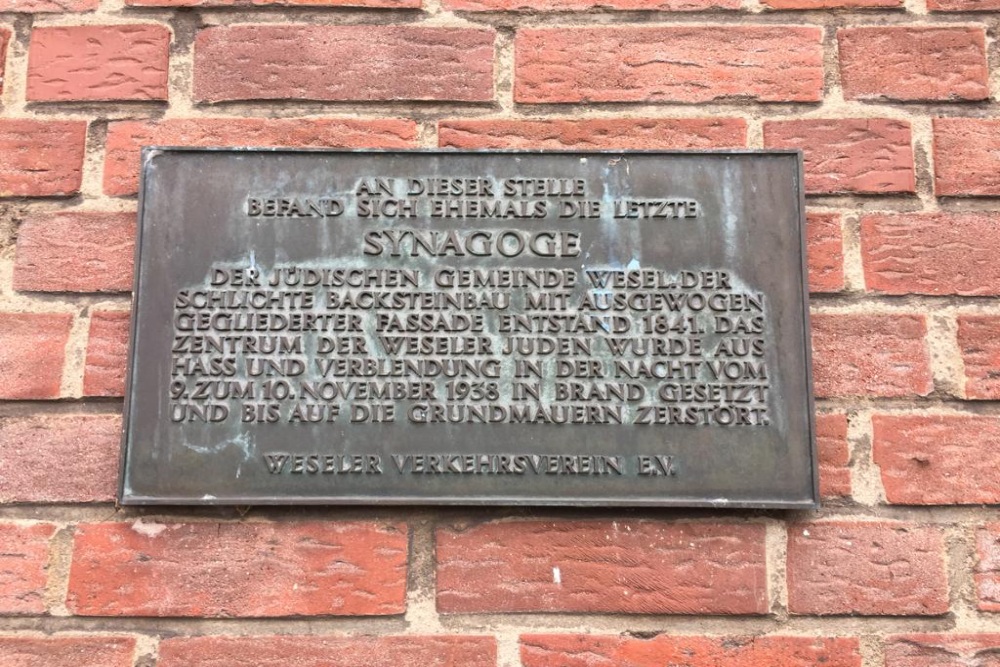

Images

Organization of the Kristallnacht

Instigated by Joseph Goebbels, a meeting with the Gauleiter and SA leaders was called in Hotel Schottenhammel following the reception in the old town hall. A party official briefed them about what to do. Instructions were then passed on by telephone to their subordinates. In the meantime, Goebbels was also busy issuing instructions. He gave the Gauleiter of Bavaria, Robert Wagner a little shove when he voiced doubts after the old synagogue on the Herzog Rudolphstraße was being demolished by SA troopers. In Berlin, Goebbels himself issued a direct order to demolish the synagogue on Fasanenstraße.

The top notch officials of SS and police were also in Munich to attend the commemoration of the putsch but they had not heard Goebbels’ speech. They heard about the action only after it had started. Reinhard Heydrich was staying in Hotel Die vier Jahreszeiten and was informed around 10:45 p.m. after the SA and the party had issued their first orders. Heydrich immediately contacted Himmler to learn how the police and the SS should act. Himmler and Hitler had attended the ceremonial inauguration of new SS members in the Feldherrnhalle – in the past the putsch had failed here on the street – and he was now in Hitler’s apartment for private talks. Probably on Hitler’s advice he decided the SS should stand aside during the protest actions. The SS shunned disorder and chaos so such actions were better suited to the SA which had never shied away from public violence.

From Gestapo headquarters at Prinz Albrechtstraße, Gestapo chief Heinrich Müller sent an urgent message by telex to all police stations in the Reich. He wrote that demonstrations against Jews could be expected all over the country. The Gestapo was not to intervene but was to cooperate with the local police to prevent looting and similar excesses. Preparations should be made for the arrest of 20,000 to 30,000 Jews and important archive material from synagogues and Jewish community centers had to be secured. As to Jews carrying weapons, his message read:

- Whenever Jews are encountered carrying weapons during the imminent actions, the most severe measures are to be taken. The SS-Verfügungstruppe and the Allgemeine-SS may be deployed in any phase of the operation. Suitable measures are to be taken to ensure that the Gestapo maintains control over the situation in all circumstances."

As early as November 8, the police had taken measures to prevent Jews from effectively offering resistance during a possible protest action. In Jewish homes, anything which could be used as a defensive weapon was confiscated. The police claimed that during a single action in Berlin, 2,569 daggers and swords, 1,702 firearms and 20,000 rounds of ammunition had been confiscated. Müller ended his telex with the announcement additional instructions would follow.

These more precise instructions came from Heydrich who sent a telex at 01:20 a.m., after his consult by phone with Himmler. Heydrich’s newsflash on the Kristallnacht reads:

- Copy of most urgent telegram from Munich of November 10, 1938, 01:20 a.m.

To:

All headquarters and stations of the State Police

All districts and sub districts of the SD

Urgent! For immediate attention of Chief or his deputy.

Following the attempt on the life of Secretary of the Legation Von Rath in Paris, demonstrations against the Jews are to be expected in all parts of the Reich in the course of the coming night, November 9/10, 1938. The instructions below are to be applied in dealing with these events:

1. The Chiefs of the State Police, or their deputies, must immediately upon receipt of this telegram contact, by telephone, the political leaders in their areas - Gauleiter or Kreisleiter - who have jurisdiction in their districts and arrange a joint meeting with the inspector or commander of the order police to discuss the arrangements for the demonstrations. At these discussions the political leaders will be informed that the German police has received instructions, detailed below, from the Reichsführer SS and the Chief of the German police, with which the political leadership is requested to coordinate its own measures:

a) Only such measures are to be taken as do not endanger German lives or property (i.e., synagogues are to be burned down only where there is no danger of fire in adjacent buildings).

b) Places of business and apartments belonging to Jews may be destroyed but not looted. The police is instructed to supervise the observance of this order and to arrest looters.

c) In commercial streets particular care is to be taken that non-Jewish businesses are completely protected against damage.

d) Foreign citizens - even if they are Jews - are not to be molested.

2. On the assumption that the guidelines detailed under paragraph 1 are observed, the demonstrations are not to be prevented by the police, which is only to supervise the observance of the guidelines.

3 On receipt of this telegram police will seize all archives to be found in all synagogues and offices of the Jewish communities so as to prevent their destruction during the demonstrations. This refers only to material of historical value, not to contemporary tax records, etc. The archives are to be handed over to the locally responsible officers of the SD.

4. The control of the measures of the Security Police concerning the demonstrations against the Jews is vested in the organs of the state police, unless inspectors of the Security Police have given their own instructions. Officials of the criminal police, members of the SD, of the Reserves and the SS in general may be used to carry out the measures taken by the Security Police.

5. As soon as the course of events during the night permits the release of the officials required, as many Jews in all districts - especially the rich - as can be accommodated in existing prisons are to be arrested. For the time being only healthy male Jews, who are not too old are to be detained. After the detentions have been carried out, the appropriate concentration camps are to be contacted immediately for the prompt accommodation of the Jews in the camps. Special care is to be taken that the Jews arrested in accordance with these instructions, are not ill-treated.

The regular police was to seal off destroyed shops and secure them. Rudolf Hess issued a similar order to the Gauleiter: "On explicit orders from the highest level, no arson shall take place in Jewish shops and such, whatever the situation."

No single order though prohibited setting fire to synagogues and Jewish community centers. As the SS and the police were clearly informed about the instructions concerning the protest actions, members of the SA were not informed of this particular order from Heydrich. They had the impression they had been given a free hand and hence, that night a huge eruption of ruthless violence took place against which the SS and the police were powerless.

Definitielijst

- Gauleiter

- Leader and representative of the NSDAP of a Gau.

- Gestapo

- “Geheime Staatspolizei”. Secret state police, the secret police in the Third Reich.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Kristallnacht

- The night of 9-10 November 1938. Over 250 German synagogues were destroyed. Tens of thousands of Jews were arrested.

- putsch

- Coup, often involving the use of violence.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- synagogue

- Jewish house of prayer.

Images

Kristallnacht

During the night of November 9 and 10, 1938, party fanatics, in particular SA troopers, had been ordered to spread terror within the Jewish community in Germany and the occupied countries. Many of them had previously attended the commemoration of the putsch and were drunk. In particular synagogues had to suffer but shops owned by Jews, Jewish department stores, community centers and homes were destroyed by the Nazis as well. Merchandise was stolen or thrown out onto the streets just like destroyed furniture and other personal belongings taken from Jewish homes. Individual Jews were also molested, sometimes resulting in death.

Goebbels had returned to his hotel at midnight after having attended the swearing-in of SS recruits in the Feldherrnhalle. He saw a red glow in the air, caused by the burning synagogue on Herzog-Rudolphstraße. He returned to the headquarters of the Gau where he was told that 75 synagogues had been put on fire, 15 in Berlin. The fire brigade was instructed only to prevent fire from spreading to adjacent buildings. Meanwhile, Goebbels had also learned that the Gestapo had issued the order to arrest 30,000 Jews. Goebbels was highly satisfied with the protest actions and he wrote in his diary: "From now on, those dear Jews will think twice before shooting a German diplomat out of hand. And that was the object of the exercise."

Nothing and nobody was spared by the mob; in Dinslaken, even a Jewish orphanage had to suffer. Someone responsible for the orphanage, possibly the manager, described his or her experiences of the night as follows:

- ...I recognized a Jewish face. In a few words the stranger explained to me: "I am the president of the Jewish community of Düsseldorf. I spent the night in the waiting-room of the Gelsenkirchen Railway Station. I have only one request - let me take refuge in the orphanage for a short while. While I was traveling to Dinslaken I heard in the train that anti-Semitic riots had broken out everywhere, and that many Jews had been arrested. Synagogues everywhere were burning!"

With anxiety I listened to the man's story; suddenly he said with a trembling voice: "No, I won't come in! I can't be safe in your house! We are all lost!" With these words he disappeared into the dark fog which cast a veil over the morning. I never saw him again.

In spite of this Job's message I forced myself not to show any sign of emotion. Only thus could I avoid a state of panic among the children and tutors. Nonetheless I was of the opinion that the young students should be prepared to brave the storm of the approaching catastrophe. About 7:30 A.M. I ordered 46 people - among them 32 children - into the dining half of the Institution and told them the following in a simple and brief address:

"As you know, last night a Herr von Rath, a member of the German Embassy in Paris, was assassinated. The Jews are held responsible for this murder. The high tension in the political field is now being directed against the Jews, and during the next few hours there will certainly be anti-Semitic excesses. This will happen even in our town. It is my feeling and my impression that we Vienna Jews have never experienced such calamities since the Middle Ages. Be strong! Trust in God! I am sure we will withstand even these hard times. Nobody will remain in the rooms of the upper floor of the building. The exit door to the street will be opened only by myself! From this moment on everyone is to heed my orders only!"

After breakfast the pupils were sent to the large study hall of the Institution. The teacher in charge tried to keep them busy.

At 9:30 A.M. the bell at the main gate rang persistently. I opened the door: about 50 men stormed into the house, many of them with their coat or jacket collars turned up. At first they rushed into the dining room, which fortunately was empty, and there they began their work of destruction, which was carried out with the utmost precision. The frightened and fearful cries of the children resounded through the building. In a stentorian voice I shouted: "Children, go out into the street immediately!" This advice was certainly contrary to the orders of the Gestapo. I thought, however, that in the street, in a public place, we might be in less danger than inside the house. The children immediately ran down a small staircase at the back, most of them without hat or coat - despite the cold and wet weather. We tried to reach the next street crossing, which was close to Dinslaken's town hall, where I intended to ask for police protection.

Just like anywhere else in the Reich where Jews did not need to count on police protection, this applied to Dinslaken as well. A police officer announced that Jews were not to get protection by the police and the children and their tutors were forcibly driven back to the orphanage where they were to remain under any circumstance. The work of destruction had not yet finished here, as appears from the sequel of the eyewitness account:

- About ten policemen were stationed there, reason enough for a sensation seeking mob to await the next development. This was not very long in coming; the senior police officer, Freihahn, shouted at us: "Jews do not get protection from us! Vacate the area together with your children as quickly as possible!" Freihahn then chased us back to a side street in the direction of the backyard of the orphanage. As I was unable to hand over the key of the back gate, the policeman drew his bayonet and forced open the door. I then said to Freihahn: "The best thing is to kill me and the children, then our ordeal will be over quickly!" The officer responded to my "suggestion" merely with cynical laughter. Freihahn then drove all of us to the wet lawn of the orphanage garden. He gave us strict orders not to leave the place under any circumstances. Facing the back of the building, we were able to watch how everything in the house was being systematically destroyed under the supervision of the men of law and order - the police. At short intervals we could hear the crunching of glass or the hammering against wood as windows and doors were broken. Books, chairs, beds, tables, linen, chests, parts of a piano, a radiogram, and maps were thrown through apertures in the wall, which a short while ago had been windows or doors.

Naturally, the pogrom did not remain unnoticed among the German citizens: many observed the catastrophe unfolding before their eyes. Some citizens were shocked but others encouraged the destruction and even participated in it. The massive destruction of the orphanage in Dinslaken likewise drew a large crowd:

- In the meantime the mob standing around the building had grown to several hundred. Among these people I recognized some familiar faces, suppliers of the orphanage or trades people, who only a day or a week earlier had been happy to deal with us as customers. This time they were passive, watching the destruction without much emotion.

The Berlin correspondent of the "London Daily Telegraph", Hugh Carleton Greene also witnessed the destructions and was astonished about the behavior of the onlookers of the pogrom. Later in the day he wrote:

- Mob law ruled in Berlin throughout the afternoon and evening and hordes of hooligans indulged in an orgy of destruction. I have seen several anti-Jewish outbreaks in Germany during the last five years, but never anything as nauseating as this. Racial hatred and hysteria seemed to have taken complete hold of otherwise decent people. I saw fashionably dressed women clapping their hands and screaming with glee, while respectable middle-class mothers held up their babies to watch the "fun".

In Dinslaken, the misery lasted until late in the morning. Meanwhile, the Jewish children had been assembled in the garden of the school, marked as the gathering point for Jews. The eyewitness account continues:

- At I0:I5 a.m. we heard the wailing of sirens! We noticed a heavy cloud of smoke billowing upward. It was obvious from the direction it was coming from that the Nazis had set the synagogue on fire. Very soon we saw smoke clouds rising up, mixed with sparks of fire. Later I noticed that some Jewish houses, dose to the synagogue, had also been set alight under the expert guidance of the fire-brigade. Its presence was a necessity, since the firemen had to save the homes of the non-Jewish neighborhood…

In the schoolyard we had to wait for some time. Several Jews, who had escaped the previous arrest and deportation to concentration camps, joined our gathering. Many of them, mostly women, were shabbily dressed. They told us that the brown hordes had driven them out of their home, ordered them to leave everything behind and come at once, under Nazi guard, to the schoolyard. A SA trooper in charge ordered some bystanders to leave the schoolyard "since there is no point in even looking at such scum!"...

In the meantime our "family" had increased to 90, all of whom were placed in small hall in the school. Nobody was allowed to leave the place. Men considered physically fit were called for duty. Only those over 60 - among them people of 75 years of age - were allowed to stay. Very soon we learned that the entire Jewish male population under 60 had already been transferred to the concentration camp at Dachau. During their initial waiting period, while still under police custody, the Jewish men had been allowed to buy their own food. This state of affairs, however, only lasted for a few hours.

I learned very soon from a policeman, who in his heart was still an anti-Nazi, that most of the Jewish men had been beaten up by members of the SA before being deported to Dachau. They were kicked. slammed in the face and subjected to all kinds of humiliation. Many of those subjected to these kinds of abuse had served in the German army during World War One.

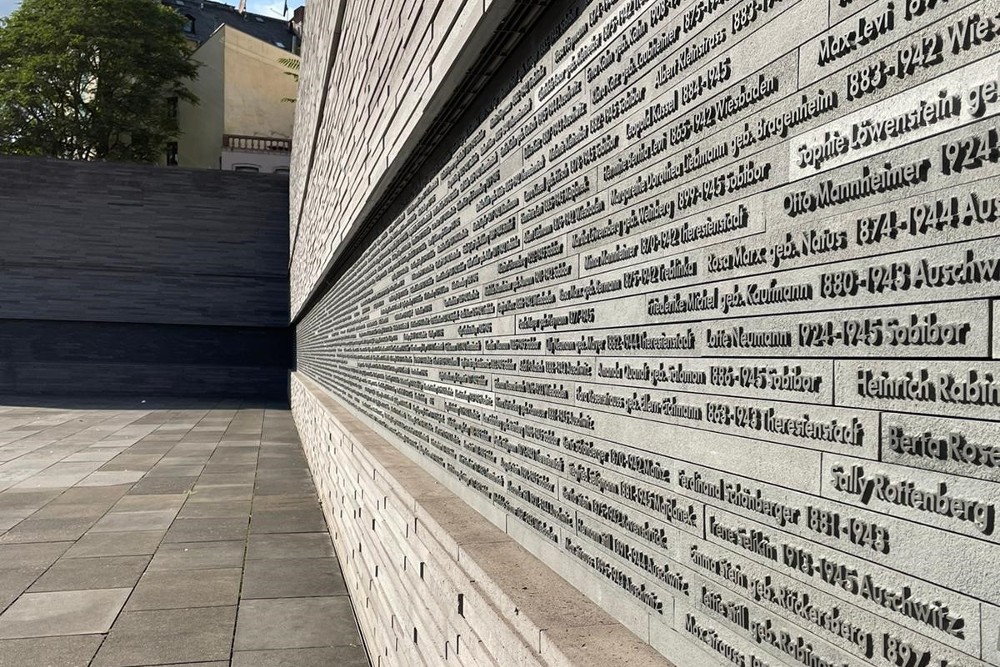

The scene that unfolded in Dinslaken was characteristic for the situation in the majority of German cities. The figures are chilling. During the pogrom – lasting some 24 hours – the first organized pogrom in Germany since the Middle Ages, at least 7,500 shops, 29 department stores, and 171 houses were destroyed. 191 synagogues were burned down and 76 damaged in some other way. 11 Jewish community centers, chapels and similar buildings were also put to the torch.

The human suffering can hardly described in numbers. Jews, including women, children and the elderly were beaten up and brutally molested. There were numerous casualties including some serious; probably some 600 people were permanently disabled. Although Reinhard Heydrich announced after the pogrom, 36 Jews had lost their lives, in January 1939 it was admitted that number stood at 91. Estimates after the war indicate 236 dead including 43 women and 13 children. Numerous Jews committed suicide that night. Out of the 30,000 Jews who were interned in concentration camps Dachau, Buchenwald or Sachsenhausen numerous others – some sources claim a number of 2,500 – lost their lives as a result of brute treatment. 7 Arians and 3 foreigners were also arrested and put in Schützhaft - preventive detention – ostensibly for their own safety.

Definitielijst

- bayonet

- Pointed weapon that can be placed at the end of a rifle and used in man-to-man combat.

- brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Dachau

- City in the German state of Bavaria where the Nazis established their first concentration camp.

- Gau

- “Shire”. District in the Third Reich established by the NSDAP.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- putsch

- Coup, often involving the use of violence.

- synagogue

- Jewish house of prayer.

- trooper

- Short for paratrooper.

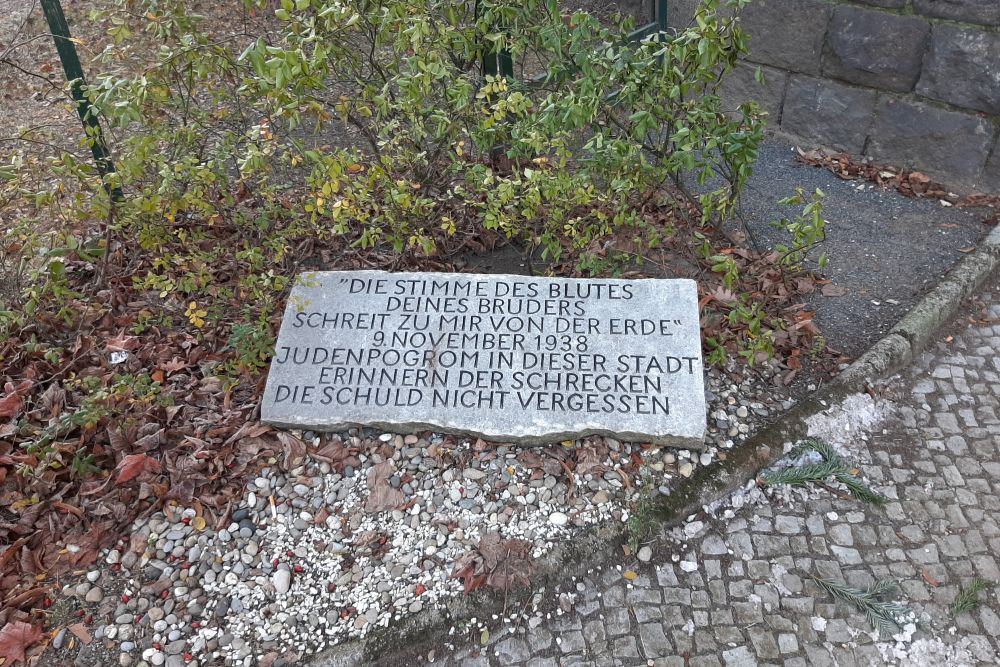

Images

The morning after Kristallnacht

In the morning of November 10, the street view in German cities was determined by the damage inflicted the night before. Most clearly visible were the smashed windows and the shattered glass on the sidewalks. Because of these pieces of broken glass, the night became mockingly known as Kristallnacht or Reichskristallnacht. This euphemistic term was frequently used in Nazi propaganda because the glow and glitter of crystal matched well with the positive approach to the pogrom that was being promoted. Moreover, this designation gave the impression that only a few window panes had been smashed which was of course furthest from the truth. Although today, the term Kristallnacht is widely used in Dutch language, abroad the term is somewhat questionable. Anglo-Saxon sources sometimes use the term Night of Broken Glass in order to avoid the ironic Kristallnacht. In the German language, some prefer the term Pogromnacht although this term, in contrast to Kristallnacht, is in fact too general to express the uniqueness of this occurrence. In Dutch, as well as in German and English, the term Novemberpogrom is used but the fact is that generally speaking, the term Kristallnacht is the most fitting to describe this historic event.

Throughout the morning, reports about the destruction were forwarded to Nazi authorities. Joseph Goebbels discussed the situation with Hitler and, influenced by the growing criticism by the highest Nazi echelons, it was decided that an end should be called to the demonstrations. Goebbels issued a decree in which he wrote cynically that when violence was accepted any longer "all kinds of scum will join in." In an official announcement he argued that he considered the acts of violence "the justified and understandable anger of the German nation about the cowardly murder of a German diplomat." He denied the numerous lootings and only wrote about "a few isolated cases" in which "old women probably had taken some trinkets or pieces of clothing for a Christmas present. Robbery or an attempt at robbery has not taken place".

Hermann Göring also played down the violence. In his words: "not a single Jew has been harmed. Thanks to the outstanding discipline of the German population, only a few windows panes have been smashed during the riots." In Nazi propaganda, the pogrom was depicted as a spontaneous outburst of popular anger. That higher authority had incited to public violence was vehemently denied. Probably not much value was attached to this official standpoint as anyone could have seen with their own eyes that mainly members of the SA and other party-connected organizations had been involved in the destructions. The party court later admitted "political actions like those of November 9 have been organized and executed by the party, whether it admits it or not."

Definitielijst

- Kristallnacht

- The night of 9-10 November 1938. Over 250 German synagogues were destroyed. Tens of thousands of Jews were arrested.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

Images

Response by German citizens

The response by German citizens to the public violence varied. During this particular night, some citizens had contributed to the outburst of destruction and violence. In some cases, even people with a prominent position in society had made themselves guilty of misconduct like in Düsseldorf where physicians from a local hospital had probably taken part in the violence. A large part of the citizens did not take part in the destruction and the violence directly but were involved in the looting of Jewish shops and department stores. Their motivation was not so much as hatred but sooner material envy or pure greed. On the other hand, there were people who lent material support or offered consolation to Jewish victims. The majority however seemed to have taken a passive attitude towards the tragedy that unfolded itself before their eyes during the pogrom. From the reactions of citizens after the Kristallnacht, it also appears that they hardly protested against the public violence and the destruction out of humane reasons.

Sopade, the leadership of the social democrats in exile reported: "such excesses are strongly objected to by the better part of the population," but it was also established that few citizens had protested against the pogrom. In a report of Sopade of December 1938, the following can be read about this:

- The broad mass of the people has not condoned the destructions but we must not forget that there are people in the working class who do not protect the Jews. Recently, incidents have occurred (..) Berlin: the attitude of the civilians was not unanimous. As the Jewish synagogue was on fire (..), one could hear a large number of German women scream: "This is like it should be; pity there are no Jews inside, this would be the best way to smoke out that worthless scum." Nobody dared oppose these sentiments openly. If there has been any speaking out in the Reich against the Jewish pogroms, the excesses of arson and looting, it has been in Hamburg and the neighboring Elbe district. People from Hamburg are not generally anti-Semitic and the Jews of Hamburg have assimilated far more than Jews in other parts of the Reich.

Source: Saul Friedlander: Nazi Germany and the Jews, Vol. 1 The years of persecution, 1933 – 1939. (New York 1997) p. 295.

Deutschland Berichte , a Sopade news publication, expressed itself in less negative terms about the attitude of the German population. It wrote:

- "Goebbels has wanted to try and convince the world the German people is fundamentally anti-Semitic in order to justify and excuse the atrocities for which the state is responsible. Those who had the opportunity to observe the Berlin citizens during the days of the pogrom, know full well that they have nothing in common with this brown barbarism. The protest of the Berlin citizens against looting and arson and against the bad treatment of Jewish males, women and children of all ages was clear to see. You could see the disdainful looks of people, you could see gestures of indignation and you could even hear words of shame and malediction. On Weinmeisterstraße a Feldwebel of the Reichswehr and a police corporal were protecting two elderly women and 6 or 7 seven children ageist a mob of party members and helping them find a refuge.

Nazi sources also report negative reactions from the public, the emphasis being mainly on indignant reactions from an economic rather than a humane point of view. In the monthly report of the President of Unterfranken, published on December 9, 1938, the attitude of the population is described as follows:

- A majority, especially among the rural population, regret the destruction of valuable goods, caused by these actions that in regard to our position as to raw materials, had better been beneficial to the entire society.

A similar report by the Regierungspräsident of Schwaben, published on December 7, 1938, contains something very similar:

- The murder by a Jew of the third secretary of the embassy in Paris has evoked angry reactions in all layers of the population. Generally speaking it was expected the central government would take some kind of action. This caused a full understanding of the legal measures imposed on the Jews. Yet, the majority of the population showed far less understanding and sympathy for the manner in which the spontaneous action against the Jews was executed. (..) The smashing of windows, the destruction of merchandise in shops and furniture in homes was considered an unnecessary destruction of valuable possessions which eventually turned into a loss of riches of the German nation. This destruction was clearly a direct contradiction of the aims of the Four Year Plan and in particular with the recently completed collection of second hand goods. (..) Furthermore, these events caused an unwanted expression of sympathy for Jews in the cities and rural areas.

Despite the inconsistencies in these sources, it is conspicuous that no impression whatsoever is made of the population unanimously backing the public violence. It would not be correct either to claim that this pogrom had enjoyed the full support of the German population because in the shops that were destroyed, German citizens had been regular customers up till then. Without the clientele the Jewish shop owners had among the German population, Kristallnacht would not have been necessary at all. After all, the protest action served a predominantly economic goal and the central government wanted to bring about the exclusion of Jews from the German economy that proved to be unachievable up till then. What anti-Semitic propaganda had not been able to accomplish, was now achieved by harsher methods.

These harsher methods were initially the violent protest action following the attempt on Ernst von Rath. A large part of the German population did not back this, out of compassion for the Jews but to a large extent out of dissatisfaction about the massive economic damage. Public violence was also considered unfitting in German culture and a step backwards in time. Reinhard Heydrich also was of this opinion because he called: "wild scenes like Kristallnacht an economic mess." He preferred a silent, bureaucratic form of terror over such public chaos, caused by gangs of drunken SS troopers.

In addition to the public violence, the anti-Jewish policy imposed by the government consisted mainly of legal suppression. Prior to Kristallnacht, laws had been issued in order to bring about the exclusion of Jews from society. The Kristallnacht was the occasion for an enlargement of this package of anti-Jewish laws. The German population hardly protested against this, neither before Kristallnacht nor after. Summing it all up we can maintain that the public violence was condemned by a large part of the German population but on the other hand there was no compunction against Jews being treated in a bureaucratic and legal manner. What happened inside the offices of the SS and the party regarding the Jews drew sporadic protest only. Only once, there was a question of collective protest against the handling of the Jewish problem in Germany when in February and March 1943, Arian women in the Rosenstraße in Berlin protested in their masses against the arrest of their Jewish husbands. The - the extermination of European Jews - took place, shrouded in secrecy and from then on, pogroms in Germany were avoided in order to prevent negative responses of citizens.

Definitielijst

- Four Year Plan

- A German economic plan focussing at all sectors of the economy whereby established production goals had to be achieved in four years time.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Kristallnacht

- The night of 9-10 November 1938. Over 250 German synagogues were destroyed. Tens of thousands of Jews were arrested.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Reichswehr

- German army during the Weimar republic.

- synagogue

- Jewish house of prayer.

Images

Response from abroad

Kristallnacht had not only drawn indignation among German citizens but abroad there were also shocked reactions to the violence in the night of November 9 and 10. Condemning articles had appeared in foreign media and the international Jewish community voiced vehement protests. Some countries decided to take in more Jewish refugees but in general, few concrete measures were taken that constituted an effective protest against the treatment of Jews in Germany. President Franklin Roosevelt for instance recalled the American ambassador in Germany in a symbolic gesture of protest but further measures by the United States, for instance an economic boycott, failed to materializer. The immigration quotum was raised but at the end of 1939, 309,000 Jewish refugees from Germany, Austria and Czechia had applied for asylum in the United States while the immigrant quotum stood at 27,000.

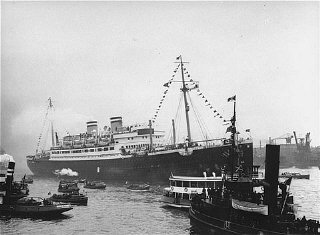

As some countries were willing to take in more Jewish refugees, numerous Jews found a safe haven. Following Kristallnacht, Great Britain for instance was willing to take in Jewish children below the age of 17. The action, known as the Kindertransport, eventually saved the lives of 10,000 children. The Jewish refugees aboard the German vessel St. Louis met an unfortunate fate however. This vessel departed from Hamburg, destination Cuba on May 13, 1939, carrying 936 passengers of which the majority was Jewish. On May 5 however, the Cuban authorities revoked their visa so when the vessel docked in Havana harbor, no one was allowed to disembark. In the end, after a long wandering voyage, the vessel returned to Europe. Most of these refugees were murdered by the Nazis, just like the majority of the other European Jews.

Despite the limits on immigration in foreign countries, some 282,000 Jews managed to escape from Germany until September 1939. Another 117,000 Jews managed to flee from Austria. The United States took in 95,000 refugees, 60,000 were taken in by Palestine, 40,000 by Great Britain and some 75,000 by Central and South-American countries, the largest numbers being taken in by Argentina, Brazil, Chili and Bolivia. Over 18,000 managed to flee to Shanghai as well, occupied by Japan at the time. Jewish refugees who had fled to countries like the Netherlands, Belgium and France only found temporary shelter: after these countries had been occupied by Germany, the tragedy started all over again for them. At the end of 1939, some 202,000 Jews remained behind in Germany and 57,000 in Austria. In Poland, other Eastern European countries as well as in the Soviet Union, many Jews remained behind, awaiting the tragedy that was looming on the horizon.

Abroad, Kristallnacht could have drawn attention to the handling of the Jewish problem by the Nazis but not enough to visualize the actual severity of the ultimate fate of the European Jews. However, nobody could have been informed yet of this ultimate fate: systematic physical extermination as the tackling of the Jewish problem took on a radical and disastrous form as late as 1941. In the days following Kristallnacht, a number of radical proposals were put forward though in order to solve the Jewish problem but large scale murder was not yet being considered seriously.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Kristallnacht

- The night of 9-10 November 1938. Over 250 German synagogues were destroyed. Tens of thousands of Jews were arrested.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Images

Response from Nazi circles

Although Joseph Goebbels appeared to be very pleased with the effect of the pogrom, directed by him, many of his colleagues within the party and the government voiced their disapproval about the massive chaos that had been caused. During a Christmas reception, Hjalmar Schacht, former Minister of Economic Affairs and President of the Reichsbank until 1939, voiced his comments about the pogrom as follows:

- Setting fire to Jewish synagogues, the destruction and plundering of Jewish stores and businesses and the mistreatment of Jewish citizens was such a shameless and outrageous action that every decent minded German must blush in crimson shame.

It is hard to judge what Schacht’s major reason for this vehement criticism had been but there can be no doubt that the effect this pogrom had on the economy was an important factor in his decision making. Shortly after Kristallnacht, Reinhard Heydrich estimated the damage at a few million Reichsmark and it was mainly this economic damage that met with the disapproval of many other high ranking party members and government officials. In particular Hermann Göring, Commissioner of the Four Year Plan was highly indignant about the enormous economic chaos that had been caused by the pogrom. Göring had not been involved in the organization of Kristallnacht and after having attended the commemoration of the putsch in Munich he had left for Berlin on his private train. As the highest ranking person responsible for the economy he had encouraged citizens to collect empty tooth paste tubes, rusty nails and other waste to be re-used and he could not stand that valuable possessions had been ruthlessly destroyed.

Even from within the SS there were indignant reactions to the damage inflicted. On November 14, 1938, Karl Wolff, Himmler’s chief of staff, told the representative of the League of Nations Burckhardt that the Reichsführer-SS condemned the pogrom. Admittedly, Heydrich and Himmler had been involved in the organization of the pogrom, contrary to Göring but they had surely wanted to prevent such economic damage, as becomes evident from the telex Heydrich had sent in the early morning of November 10 in which he called for prevention of looting. The indignation within the SS about the disorder during Kristallnacht may well have been an expression of discontent about the fact that they had been unable to prevent looting and other unwanted disorders. In any case, we can say that the chaos of Kristallnacht did not match the bureaucratic work methods of the SS. From the moment Himmler and Heydrich were put in charge of the solution of the Jewish question, they have never applied a method like this. Of course, the solution of the Jewish question the SS applied from 1941 onwards was far too gruesome to be executed in public.

In addition to Göring, Himmler and Heydrich, for instance Joachim von Ribbentrop, Minister of Foreign Affairs and his colleague of Internal Affairs, Wilhelm Frick voiced their indignation about Kristallnacht. What was the reaction of the all important person within the Nazi state? What did Adolf Hitler think about Kristallnacht? A question difficult to answer which can only become clear when we know the exact role he played in the organization of the pogrom. Although Goebbels was obviously the initiator and instigator of the pogrom, it is very likely Hitler consented to Goebbels’ plans. Everything points to Hitler having given his permission during the personal conversation he had with Goebbels during the reception in the old town hall. Goebbels wrote about his conversation: "I explained the situation to the Führer. He decides: Let the demonstrations continue. Withdraw the police. The Jews shall have to feel the anger of the people for once." It is quite possible Goebbels misunderstood Hitler’s words, whether on purpose or not and that he drew his own conclusion but there is another indication that seems to confirm Hitler giving his permission for Kristallnacht.

Around midnight, Himmler had a private conversation with Hitler in the latter’s apartment. Meanwhile, Heydrich had been informed of the disorders and phoned Himmler. He decided the SS should stand aside and although it is hard to prove, it is very likely Hitler knew about this conversation and was even involved in this decision making. Despite the vagueness about the subject of this conversation between Goebbels and Hitler and his involvement in the phone call between Himmler and Heydrich, chances are he made the decision at both decisive moments. Neither before nor after Kristallnacht though, Hitler took no responsibility whatsoever for the pogrom but this of course matched perfectly with the propaganda image of a spontaneously erupting protest.

In the days after Kristallnacht some high ranking Nazis, for instance Albert Speer and Alfred Rosenberg had the impression Hitler condemned the public violence. In public however, he never condoned nor condemned the pogrom. During a lunch on November 10, 1938 with Goebbels however, Hitler indicated he would take draconic measures against the Jews. In addition he announced, the Jews were to pay themselves for the damages inflicted by their attackers. There are no indications that Hitler distanced himself from his propaganda minister- a few days later they even went to the theatre together – and it looks like Hitler’s disapproval, of which Speer and Rosenberg spoke, was only meant to put them at ease and to ensure that such incidents were never to occur again.

Despite Hitler’s role as to the organization of the pogrom and his ultimate view on the matter not being certain, it can be safely assumed he made no attempt whatsoever to prevent the pogrom and during the days after, he was not involved in the final dealing of the problem. He was not present at the meeting of November 12, 1938 when the consequences of Kristallnacht and the further tackling of the Jewish problem were being discussed. This meeting, just like the organization of Kristallnacht, was a fine example of "working towards the Führer," as historian Ian Kershaw describes the political decision making in the Third Reich in his two-volume biography of Hitler. Being the organizer of Kristallnacht, Goebbels thought he had to do what Hitler expected him to do; just like those present at the meeting of November 12 tried on their own initiative to formulate a policy which they thought would match Hitler’s views.

Definitielijst

- Four Year Plan

- A German economic plan focussing at all sectors of the economy whereby established production goals had to be achieved in four years time.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Kristallnacht

- The night of 9-10 November 1938. Over 250 German synagogues were destroyed. Tens of thousands of Jews were arrested.

- League of Nations

- International league of Nations for cooperation and security (1920 – 1941). The League was located in Geneva, in neutral Switzerland. During the 1930s the league of nations could do little against aggressive behaviour of Japan, Manchuria, Italy, Abyssinia and Hitler. The league of nations was in fact the predecessor of the United Nations.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- putsch

- Coup, often involving the use of violence.

Images

Decision making after Kristallnacht

On occasion of Kristallnacht, an important meeting was called on November 12, 1938 at the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (state department of aviation). Subject of the meeting was the Jewish question as Martin Bormann, chief of staff of Hitler’s deputy Rudolph Hess had informed Hermann Göring in a letter that Hitler desired a co-coordinated solution of the Jewish question. The meeting was attended by a large number of representatives of German and Austrian ministries and government agencies. Present among others: Joseph Goebbels and other employees of the Ministry of Propaganda, Reinhard Heydrich on behalf of the SS, SD and Kripo, Kurt Daluege on behalf of the German police and Ernst Wörmann on behalf of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Others present were Minister of Internal Affairs Wilhelm Frick, Minister of Economic Affairs Walter Funk and Minister of Finance Graf Lutz Schwerin von Krosigk. The Austrian Minister of Finance, Dr. Hans Fischböck was present as well.

After Göring had indicated that the goal of the meeting was to take a decision as to the exclusion of Jews from German economy, he talked about Kristallnacht. He voiced vehement protests about the violent actions which had taken place. He indicated that not the Jews had suffered during this pogrom but the Reich. The problem was that a major part of the damage, estimated at 25 million RM by a representative of the insurance branch, officially had to paid out to the Jews. This of course constituted an enormous loss for the insurance companies and the Reich would surely not benefit from it. Another problem was that most of the destroyed buildings were rented by Jewish entrepreneurs and consequently the Arian owners were the ones to suffer most. A further estimate revealed that replacing the shattered window panes would cost 6 million RM in total. An additional problem was that production of this glass would take six months at least and had to be paid for with valuable foreign currency.

It was obvious that Kristallnacht had serious consequences for the Reich but a solution was at hand. It was decided that the insurance companies were to pay for all damages but the losses the Jews had suffered were to be paid out to the Ministry of Finance. In order to have the Reich benefit still more it was also decided to impose an appeasement fine on the Jews of 1 billion RM. This fine represented about 20% of all Jewish possessions. The fine was meant to emphasize that not the Germans were responsible for Kristallnacht but the Jews; after all, in the eyes of the Nazis, they had triggered this so-called justified spontaneous outburst of violence by the attempt on the employee of the embassy.

In the course of the meeting, Goebbels emphasized he deemed it necessary to exclude the Jews from social life as well. In Berlin he had already taken various measures accordingly but he desired emulation in the entire Reich. A few measures he proposed were banning Jews from entering cinemas, theatres, parks, beaches and swimming pools. He also found it disgusting that Jewish children were still able to go to German schools. Göring frequently reacted cynically to Goebbels’ remarks. He probably was still angry at the propaganda minister because of the difficult position he had been put in: after all, as senior responsible for the German economy he had suffered most as a result of Kristallnacht.

Heydrich also tried to make various proposals during the meeting in an attempt to meet Hitler’s expectations. He proposed to oblige Jews to wear some kind of insignia but for the time being, this measure was not introduced. Establishment of Jewish ghettos was also discussed but this did not come about either as Heydrich emphasized the police was unable to maintain control over such a ghetto. Heydrich also reported that Eichmann and his Zentralstelle für Jüdische Auswanderung (Central Agency for Jewish emigration) had managed to drive 500,000 Jews from Austria and that in Germany, they had only succeeded in driving 90,000 Jews out. If expelling Jews would be continued in this way, it would taken between 8 and 10 years before all Jews had been driven out. It became increasingly clear that the measures imposed up till then would not be sufficient to drive the Jews out of Germany fast.

Although the meeting could not arrive at a definite solution as the complete elimination of Jews from the Reich, various decisions were made to further exclude Jews from economic and social life. During this meeting, the following measures – and others - were decided on and in the following 2 to 3 months:

- Insurance companies were to compensate the damage of Kristallnacht in full but only Arians could lay claim to compensation. The losses of Jews were to be paid to the Reich.

- An appeasement fine of 1 billion RM was imposed on the entire Jewish community to pay for the economic damage inflicted during Kristallnacht.

- Jewish real estate owners and tenants were to pay for the damage to their shops and homes out of their own pocket immediately.

- Not a single Jew of German nationality was allowed to bring cases, arising from the pogrom to German courts.

- As of January 1, 1939, Jews were no longer allowed to run shops or wholesale stores, to have employees, to bring ready to use products on the market, advertize or accept orders. In addition, from this day on, no Jew was allowed to lead an enterprise, occupy a managerial position or be a member of a commercial enterprise.

- Drivers licenses of Jews were revoked.

- Works of art, jewelry, precious metals and shares owned by Jews were confiscated by the Reich.

- Jews were denied entry to theatres, concert halls, cinemas and museums.

These measures caused the Jews to be increasingly on their own. They could not trade with non-Jews and although ghettos would be established later on - and then predominantly in the East – they were concentrated in separate housing blocks. Around the outbreak of war in September 1939, the economic and social exclusion of Jews was well advanced. The war and subsequent expansion of territory offered fresh opportunities for the total elimination of Jews from society but caused new problems as well: Jews living in the captured areas had to be removed too.

More about the meeting described above: Discussion Jewish question, November 12, 1938.

Definitielijst

- ghetto