1875 - 1943

Introduction

Father Lichtenberg was no stranger to war. As early as WWI he had worked as an army chaplain in the German army, and during WWII he remained true to his spiritual calling. However, his war experiences had brought him political awareness. He despised communism, and later, fascism. One motto in particular guided him in everything he did, and that was a well-known text from the Bible: You shall love your neighbour as yourself (Matthew 22:39). During WWII this would become the text Bernhard Lichtenberg frequently called upon when he protested the hideous Nazi regime.

Background

Bernhard Lichtenberg came from a small merchant’s family, who resided in the area of Breslau, Silesia. Olawa was Protestant in principle, but the Lichtenberg family belonged to a small group of Catholics. In 1875, Bernhard was born. He was the second child of the Lichtenberg family, who would eventually be blessed with 5 children. After completing grammar school, Bernhard was called into priesthood, and went on to study theology in Breslau. In 1899 he was ordained a priest, and remained working for Breslau’s Catholic community until he left for Berlin in 1913. There he served the Heart of Jesus community in Charlottenburg, a district of Berlin. Several years later, in 1932, he was ordained the Dom’s provost, second in charge of the Diocese of St Hedwig’s Church. He was concerned especially with the poor and the lonely.

However, Father Lichtenberg felt that his purpose lay beyond only serving the church. He had cultivated an interest in politics. Directly following WWI he became a member of the Catholic peace movement ‘Friedensbund Deutscher Katholiken’ (‘Peace Council of German Catholics’). In the 1920’s he was a member of the regional board of the Berlin district of Wedding and he was elected into the council of the ‘Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Konfessionen für den Frieden’ (‘Working Community of Confessionals for Peace’). When Bernhard Lichtenberg saw the power of the National Socialists grow rapidly in 1931, he called upon all his parishioners to watch the war movie Im Westen nichts Neues, based on the book of the same title by Erich Maria Remarque. That earned him comments of severe disapproval from ‘Der Angriff’, a newspaper initially founded by later propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels (Bio Goebbels).

A few years later, the National Socialists were firmly installed, and many new laws swiftly followed, which also applied to the church and its authority. An example is the old ‘Chancellor’s Paragraph’, dating from Bismarck’s time, which was reinstated. This law was an ordinance that prohibited misuse of the pulpit for political purposes. December 1934 would also see the passing of a law that prohibited slander of the state and the National Socialist Party. Needless to say, these laws almost immediately led to the arrest of many Catholic priests.

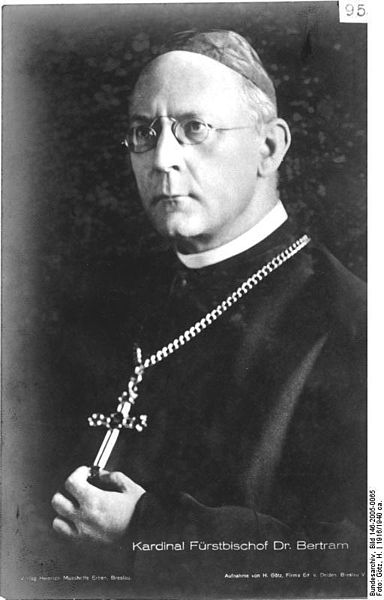

An announcement for an anti-Semitic boycott of Jewish companies would soon follow. Outraged at this news, Lichtenberg requested an audience with Cardinal and Archbishop of Breslau Adolf Betram, during which Jewish banker Oskar Wassermann was also present. Betram understood his concern, though he considered the Jewish matter a situation outside the Church’s jurisdiction. (What’s more, Cardinal Betram would later actively resist the Nazis during the war, but due to his attitude in 1933 he would remain a controversial individual.) However, this did not stop Lichtenberg from proclaiming his aversion to Nazism outside the confines of the church’s walls, which soon earned him a thorough house search by the Gestapo. This, too, did not abash the priest’s self-imposed task as a Christian, namely to help Jews. Especially those wishing to leave the country could always count on his assistance. The worst violation of human rights, however, was yet to come...

Camp Esterwegen

1933 proved a troubled year for German citizens as well. The first camps were deployed, initially for political opponents of the ‘Reich’. Among the prisoners were communists, socialists, pacifists, union members and freemasons. Camp Esterwegen was set up just outside Groningen as a penal camp for people both from Germany and abroad. Esterwegen, as Lager VII, was part of the Emslandlager, a complex made up of 15 camps with various functions, such as concentration camps, penal camps, POW-camps, and satellites of concentration camp Neuengamme. Camp Esterwegen soon established itself as a model camp, and after 1936 it became a penal camp. Every now and then, prisoners were released from Emslandlager, but not before they had received strict instructions to keep quiet about what happened in these camps. Naturally, the same held true for released prisoners from Esterwegen. However, even this pressure could not prevent news of severe torture and committed murders leaking to the outside world. In Esterwegen, guards shot at prisoners as a means of pastime, who ran and scattered in panic, often straight towards the electrified fence.

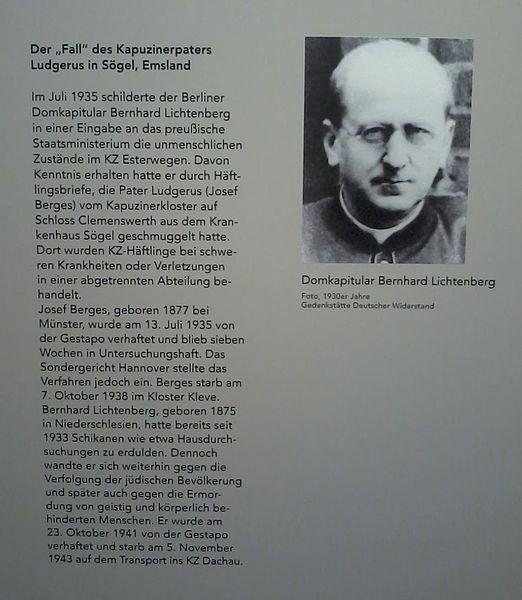

Lichtenberg first received news of these atrocious conditions in 1935, and he again protested. This made Bernhard Lichtenberg one of the few, if not the only, priest who voiced criticism of the horrors taking place in the concentration camps. In the spring of 1935 he took the brave decision to send an extensive report of the treatment of prisoners in Esterwegen to Reichsmarshall Hermann Göring. No reply ever came, nor did a change in the camp guards’ attitude, but Lichtenberg did make a name for himself as a troublemaker who needed to be taken care of. The Church, however, also took an interest in the defiant priest. Berlin had acquired a new bishop as of 1932, Konrad von Preysing, and he became a close friend of the Dom’s provost. He also advocated the rights of those prosecuted by the Nazi regime. Lichtenberg felt strengthened by this friendship and continued his crusade. He remained an active supporter of (mentally) ill prisoners who were suffering from the abhorrent regime. His sermons were drenched with fierce condemnation of National Socialist dogmas, also relating to Jewish brothers and sisters, for that is how he viewed them. His attitude was confirmed after the horrifying events of the night of November 9, 1938 (the Kristallnacht).

Kristallnacht

In the deep, dark, November night, all hell broke loose in Nazi-Germany. Countless Jewish-owned shops were vandalised, synagogues and other Jewish buildings were set on fire, and many Jews were arrested. A number of them were attacked or even killed in the same violent manner. But while the synagogues burned, the priests held their tongues. The only voice of protest came from Father Lichtenberg, who was fierce in his condemnation of the perpetrators: "We know what happened yesterday, we do not know what is to come. But we have experienced what happened today: outside, the temple burns. This is also a sacred house of worship." From that day onwards, the Dom’s provost prayed every day in St Hedwig’s Church, for Jews and for non-Arian Christians. For others, too, who had been affected by the regime, he prayed to God for comfort. This, however, still did not end Father Lichtenberg’s crusade. What’s more, fuelled by his anger at seeing how the old Germany was ruined by National Socialism, he became increasingly involved in ‘Earthly matters’.

Besides helping Jews to go into hiding, for which he contacted (among others) the Solf-Kreis (the cultural-political resistance froup led by Johanna Solf, who used her tea parties as a cover), he also filed a complaint against racial discrimination in air raid shelters with the city council, as well as a complaint against euthanasia programme ‘Aktion T4’. Since 1939, the disfigured or the mentally ill were systematically euthanized to keep the Arian race genetically pure. In 1941, Leonardo Conti was named Reichsgesundheitsführer (Empire’s Minister of Health), and in that capacity he was responsible for the execution of the euthanasia programme. Lichtenberg did not hesitate and wrote to the new authority, in which he described his objections against this un-Christian programme. Because of his continuous protests, it was only a matter of time before conflict with the government would arise. The Gestapo kept an even closer watch on the provost, but fate struck hard from an unexpected source.

The final battle

One day, Lichtenberg was praying aloud for the Jewish prisoners in the concentration camps. His prayer was overheard by two students, who reported him to the police. A new house search was the inevitable result. In his house, they found next Sunday’s sermon, which was a fierce reaction to an earlier propaganda pamphlet from Goebbels. It called upon the Arian Germans to refuse help to, or even conversation with, Jews. In his sermon, Lichtenberg called upon his parishioners to "love your neighbour as yourself". In addition to this argument, they also found a copy of ‘Mein Kampf’, covered in the provost’s notes. During his interrogation Lichtenberg stated that it was his duty as a Catholic priest to oppose the text, because the world described by the book went against every Christian teaching. He declared that he would fully accept any consequences that his views may lead to, as he was well aware they may. However hard the interrogations were, Lichtenberg remained true to his principles. In May 1942, the Berlin court judged that Dom’s provost Bernhard Lichtenberg was to be convicted of treason on grounds of the ‘Chancellors’ Paragraph’. The verdict was a two-year prison sentence, and he was taken to Tegel prison and later to Arbeitserziehungslager (‘work education centre’) Wuhlheide.

When the end of his sentence came nearer, Lichtenberg was visited by Bishop Preysing, who had a remarkable offer. The bishop had been approached by the Gestapo with the announcement that Lichtenberg would be released on the condition he would not preach for the remainder of the war. In October 1943, the provost was released, but soon arrested again for his continuing opposition. His new destination was to be Dachau camp. Lichtenberg, however, requested to go to Lodz instead. In Lodz, there was a Jewish ghetto, and close by was extermination camp Chelmo. Lichtenberg stated that the deportations clashed with Christian morals, and that as such he wished to guide (Christian) Jews as a clergyman on their journey to the extermination camp. Bishop Von Preysing tried with all his might to change his mind, because Lichtenberg’s health had suffered from his earlier imprisonment, and the bishop was worried about his friend. But it had been in vain, because Lichtenberg retained his position. He wanted to go to Poland. His request, however, was not acknowledged, and he was promptly deported to concentration camp Dachau. On November 5, 1943, he died in one of the many cattle carriages.

In 1965 his remains were transferred to the crypt of St Hedwig’s Cathedral in Berlin. On June 23, 1996, Pope John Paul II beatified him, and he was posthumously awarded the title Righteous Among the Nations.

Definitielijst

- communism

- Political ideology originating from the work of Karl Marx “Das Kapital” written in 1848 as a reaction to the so-called class struggle between the proletariat (labourers) and the bourgeoisie. According to Marx the proletariat would take over power from the well-to-do classes though a revolution. The communist movement aspires an ideal situation where the means of production and the means of consumption are common property of all citizens. This should end poverty and inequality (communis = common).

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- fascism

- Original name of the antidemocratic political movement in Italy under command of dictator “Il Duce” Benito Mussolini. Mussolini was the leader of Italy from 1922 to 1943. Nowadays the term fascism is a much used term for antidemocratic political movements. Sometimes German national socialism is called fascism.

- Gestapo

- “Geheime Staatspolizei”. Secret state police, the secret police in the Third Reich.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Mein Kampf

- “My Struggle”. Book written by Adolf Hitler, outlining the principles of National Socialism.

- National Socialism

- A political ideology drawn up by Hitler based on the superiority of the German race, the leader principle and fierce nationalism that was fed by the hard Peace of Versailles. National socialism was anti-democratic and racist. The doctrine was elaborated in Mein Kampf and organised in the NSDAP. From 1933 to 1945 National socialism was the basis of totalitarian Germany.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Nazism

- Abbreviation of national socialism.

- POW

- Prisoner of War.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Socialism

- Political ideology aiming at slight or no class differences. Means of production are owned by the state. Evolved as a response to capitalism. Karl Marx tried to substantiate socialism scientific.

Images

Memorial tablet for Bernhard Lichtenberg in the former Esterwegen concentration camp Source: Wikimedia.

Memorial tablet for Bernhard Lichtenberg in the former Esterwegen concentration camp Source: Wikimedia. Dr. Konrad Graf von Preysing, the new Bishop of Berlin delivers his inaugural address in 1935 Source: Bundesarchiv CC-BY-SA 3.0.

Dr. Konrad Graf von Preysing, the new Bishop of Berlin delivers his inaugural address in 1935 Source: Bundesarchiv CC-BY-SA 3.0.Information

- Article by:

- Annabel Junge

- Translated by:

- Nadia Guntlisbergen

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!