Introduction

On the 12th of December 1942, after a long and adventurous voyage, the Dutch steamship Ombilin of the Nederlandse Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij (Dutch Royal Cargo Shipping Company) was sunk by the Italian submarine Enrico Tazzoli. The crew of the Dutch ship survived the sinking and, after much travel on other vessels, managed to continue to assist the Allies. The captain and first mate of the Ombilin were taken prisoner by the Italians, and they were not freed until April 1945. This story outlines a clear picture of the many dangers crew members of merchant vessels faced during the Second World War.

Introduction of a mercantile vessel

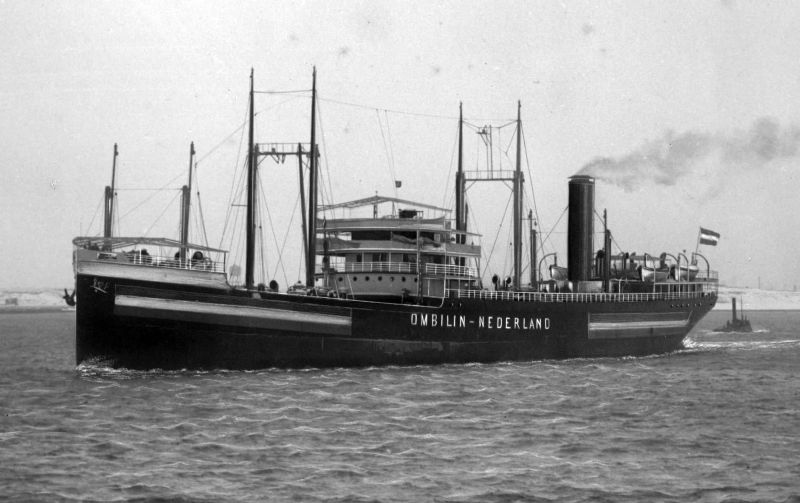

The order for the construction of the steamship Ombilin was delivered to the Nederlandse Dok en Scheepsbouw Maatschappij (NDSM) (Dutch Dock and Shipbuilding Company) in Amsterdam by the Nederlandse Koninklijke Pakketvaart Maatschappij (KPM). The KPM was a Dutch shipping company which was based in Amsterdam but had operational headquarters in Batavia on Java in the Dutch East Indies. The company maintained maritime connections to and from the Dutch colony. The Ombilinwas actually built to transport coal, but was also suited to transport other bulk materials and even general cargo. The vessel was added to the fleet of KPM in 1916. The Ombilin was for its time a large vessel with a water displacement of 5,658 tons, but only possessed a few Werkspoor Company triple expansion steam engines, which created about 2.200 horse power. The maximum speed of the riveted, steel coal loader, with a length of 128,1 meters, width of 16,5 meters and draught of 7,41 meters, amounted to only ten knots.

In 1916 the Ombilin was KPM’s biggest coal ship and the first vessel that was equipped with topside tanks to improve the stability of ship. This made it possible to speed up the loading and unloading processes. The SS Ombilin had limited facilities for passengers, as was normal at that time. (Incidentally, in 1937 the vessel provided luxurious accommodation for four lounge passengers.) In February 1916 the new steamship left the harbor of Ijmuiden and set sail towards the Dutch East Indies. Between both world wars the SS Ombilin actively transported coal and other bulk cargo. All those years it sailed under a lucky tropical constellation

On December 7th 1941, the Japanese Navy ended the prosperity of this period. On that day, they attacked the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor and crippled the American Pacific fleet. Three days later near the peninsula of Malacca on the mainland of what today is Malaysia, the British battleships HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse were sunk by Japanese planes. On 11 January 1942, the Japanese army started to conquer the first islands of the Dutch East Indies. During the night of 27-28 February, the combined fleet of the Americans, British, Dutch and Australians was crushingly defeated during the Battle of the Java Sea. After this, Java, the only remaining Allied stronghold in the Dutch colony, was left to the mercy of the Japanese conquerors. On 8 March 1942, the Dutch commander Lieutenant-General H. ter Poorten had to face defeat and signed the surrender. Singapore, the most important British stronghold, had already fallen on the 15th of February. The Japanese ‘Blitzkrieg’ had made sure that within three months almost all of Southeast Asia was occupied by the Land of the Rising Sun. However, the SS Ombilin had left the archipelago by that time.

Definitielijst

- Blitzkrieg

- The meaning of this word is “Lightning War”. Short and fast campaign. As opposed to a trench war the Blitzkrieg is very quick and agile. Air force and ground forces work closely together. First used against the Germans (September 1939 in Poland.

Images

The SS Ombilin during a shakedown cruise in February 1916. Source: Maritiem Digitaal.

The SS Ombilin during a shakedown cruise in February 1916. Source: Maritiem Digitaal. The KPM freighter Ombilin in the Dutch East Indies. Source: Maritiem Digitaal. Source: Maritiem Digitaal.

The KPM freighter Ombilin in the Dutch East Indies. Source: Maritiem Digitaal. Source: Maritiem Digitaal. The luxurious interior of the Ombilin. Source: Maritiem Digitaal.

The luxurious interior of the Ombilin. Source: Maritiem Digitaal.Odyssey of the Ombilin

On December 7th 1941, the SS Ombilin was in Singapore carrying a load of rice from Tegal on the north coast of Java. That same night Singapore was bombed by Japanese aircraft, but the Ombilin was not damaged. Nevertheless, that night, the steamship’s crew, under the command of Captain H. Ellens, was introduced to the violence of war for the first time. Because the bombings of the British colony continued, the unloading of the vessel was extremely difficult. Only after two weeks were the cargo areas empty. After that the ship had to depart for the nearby island of Bintan, located in the Riau archipelago, to load a shipment bauxite destined for America. Via Emmahaven harbor of Padang on the west coast of Sumatra, Bunbury in Southwest Australia and Wellington in New Zealand for refueling, the ship crossed the Pacific Ocean without any problems. After passing through the Panama Canal, the Dutch vessel reached the Atlantic Ocean via the Caribbean Sea where the German submarine offensive reached its height. The Ombilin still sailed beneath a lucky constellation, having reached Portland, Maine, on the northeast coast of the United States, unharmed on the 10 April 1942.

After this, in Canadian waters the Ombilin resumed carrying coal, but not before it was equipped with heavier armor and was prepared to stay in colder regions for a longer period. The Ombilin had been, after all, a vessel built to withstand tropical conditions. Furthermore, clothing had to be purchased urgently for the mainly Chinese and Javanese crewmembers. They had been walking around in their tropical clothes for several days. The Canadian Dominion Coal Company chartered the ship during the summer season, and until October 1942 the Ombilin took coal from Sydney in Nova Scotia to Montreal and other Canadian cities.

With winter approaching, the Ombilin left for Montreal in early October for extensive maintenance. Afterwards the Dutch sailed in convoy via Halifax, Nova Scotia, to New York, where a load of general cargo was taken aboard. The cargo consisted of heavy railway material, agricultural machinery, sawn timber, canons, munitions, light bulbs, paper and flour. On 8 November, the Dutch ship, again as part of a convoy, left to be reloaded in Trinidad. On 21 November, the Allied convoy arrived at the southernmost Caribbean Island. On 5 December, the Ombilin left Trinidad as part of a convoy of 18 ships heading for Cape Town, South Africa. The convoy was disbanded two days later because the ships had too many different destinations.

On the 7th of December, the SS Ombilin was located 350 miles from the South American coast, moving farther and farther away towards the east. Captain Ellens was aware of the dangers he and his crew could run into on the Atlantic Ocean. For this reason, he was constantly training his crewmen to lower and raise the lifeboats which were always turned outward so they could be launched faster. Furthermore, the lifeboats were in pristine condition and equipped with sails which could catch rainwater, which then would be transferred with hoses into barrels. Moreover, the Ombilins crew had found a resourceful solution for obtaining freshwater in case the worst would happen to the ship. They had cleaned oildrums, painted them white, filled them half-full with freshwater, and closed them tightly. The drums were placed on the open deck so if the ship were to sink they would wash overboard. Because the drums were only half full they would float. The crew of the SS Ombilin couldn’t have known all these measures would be needed much sooner than expected.

Definitielijst

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

Images

The stern of the coal tender Ombilin. Source: . Source: Maritiem Digitaal.

The stern of the coal tender Ombilin. Source: . Source: Maritiem Digitaal.Sinking of the Ombilin

At a speed of nine knots, the Ombilin slowly steamed towards South Africa. At 16:00hours, on 12 December 1942, the third helmsman H. G. Hanewinckel relieved J. Feller, the fourth helmsman of the Ombilin. It had been a calm watch, and Feller told Hanewinckel when handing over the watch, "Nothing special, good watch." Feller was about to leave the bridge when a large explosion sounded at starboard. Both Helmsmen were thrown to the deck. Feller was the first to get on his feet and he set the chadburn (engine order telegraph) at full speed astern to slow down the ship. Even though water was entering the engine room and the Javanese crew there had fled atop, Engineer L. Krijgsman carried out the order calmly. After Helmsman Hanewinckel had scrambled up, he saw thick black smoke coming out of cargo room No. 4. He also noticed that starboard longboat No. 1 had been shattered completely. After putting on his life jacket, he immediately went down to the chart room and gathered all nautical equipment, such as sextant, sea charts and binoculars. After this he hurried to lifeboat No. 2 on the starboard side, behind cargo area No. 4.

It became clear to Captain Ellens that his ship could not be saved. Out of the air vents of cargo room No. 4 blew a thick noisy flow of air reeking of burned gunpowder and coal. The hatches were laid open, the tarpaulin covers were torn, and the beams to support the hatch cover were raised upwards. Moreover, the engine room reported the rising water level. The torpedo most likely hit the Ombilin at the level of the starboard cargo hold between hull no. 4 and the starboard spare coal storage near the boiler room. Captain Ellens therefore gave the order to abandon ship. Together, he and the radio operators, A.J.H. ter Boo and A.F. Jolmers, who sent out an extensive SOS signal, threw convoy codes, the ship’s logs and other secret documents overboard in a weighted mail bag. After he checked the midships to see if anyone was left behind, he left the ship. Chief engineer T.H.C. Geenemans and second mate H.J. Visser had done the same in the stern.

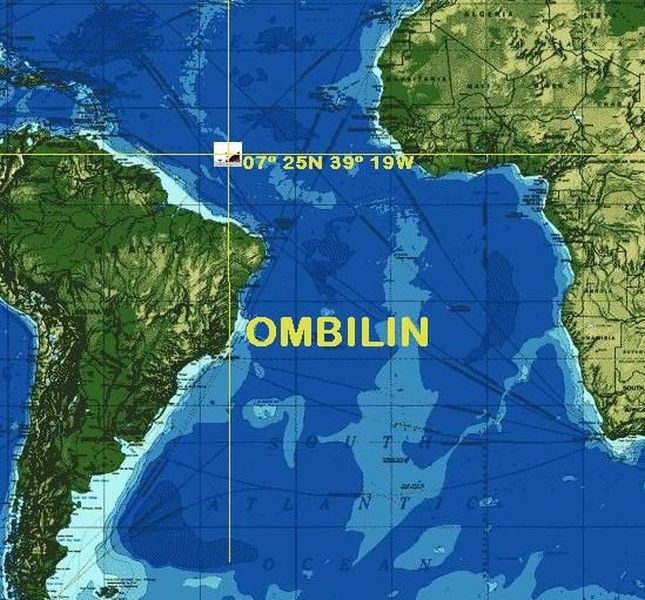

In the meantime, the three remaining lifeboats were launched into the water, as were the life rafts, which were promptly launched by Second Driver B. Jaspers. Portside lifeboat no. 2, belonging to Third Mate Hanewinckel almost failed. The back pulley was jammed, causing the lifeboat to hang forward at an angle of fifty degrees. The third mate managed to cut the pulley with an axe, making sure the boat entered the water in the right position, though with a hard landing. The third mate had to jump into the water and swim to his lifeboat. All crew members managed to reach safety in three lifeboats and life raft. At that moment, only twelve minutes after the torpedo had hit the ship, the old steamship Ombilin disappeared upright beneath the waves of the Atlantic Ocean, position 7°25’ North latitude and 39°19’ West longitude.

Part of the cargo of the Ombilin rose to the surface, covering the ocean in thousands of cheerfully floating light bulbs. Among the three lifeboats and the lightbulbs a light grey submarine, over eighty meters long, slowly emerged. Aboard the submarine the Italian flag had been hoisted, and a large part of the crew appeared excited, dressed in dirty clothes, busy handing out hand guns but most importantly photographing and filming equipment. The submarine’s commander, the long and slim capitano di corvette Carlo Fecia di Cossato, asked through a bullhorn in broken English if there were any wounded. After a negative answer by Captain Ellens, Carlo Fecia di Cossato ordered him and the first mate to board the submarine. Captain Ellens and Chief Engineer Geenemans followed these orders and were taken prisoner on the Italian vessel. After the submarine’s crew gave a can of drinking water to the remaining castaways, they disappeared under the water leaving the three lifeboats and the raft to their fate on the otherwise empty ocean.

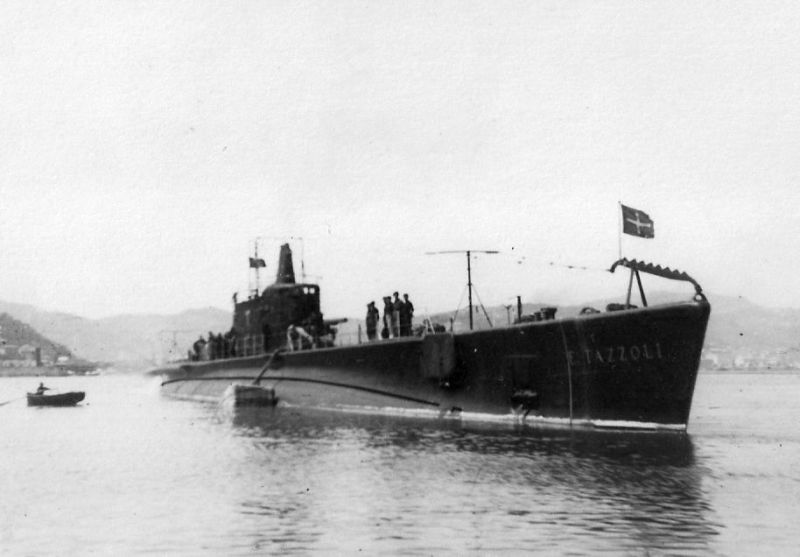

The steamship Ombilin had been sunk by the Italian Calvi-class submarine Enrico Tazzoli, which had an underwater displacement of almost 2.000 tons. The submarine, with call sign TZ, had been launched on the 14th of October 1935 at the Oderno Terni Orlando near Genoa for the Regia Marina, the Italian Royal Navy. Since 12 October 1940, the Enrico Tazzoli and her 66 crew members managed to sink fifteen Allied mercantile ships, sinking in total around 80.000 tons. This made the Enrico Tazzoli one of the most successful Italian submarines in the Battle for the Atlantic Ocean.

Definitielijst

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Images

The Italian Calvi-class submarine Enrico Tazzoli. Source: Navie Armatori.

The Italian Calvi-class submarine Enrico Tazzoli. Source: Navie Armatori. The commissioning of the Enrico Tazzoli. Source: Regia Marina. Source: Regia Marina.

The commissioning of the Enrico Tazzoli. Source: Regia Marina. Source: Regia Marina. The Commander of the Enrico Tazzoli, capitano di corvetta Carlo Fecia di Cossato. Source: Wikipedia.

The Commander of the Enrico Tazzoli, capitano di corvetta Carlo Fecia di Cossato. Source: Wikipedia.Fate of the Ombilin crew

After the Italian submarine had departed, all the Dutch castaways of the Ombilin got into the three life boats. The rations and drinking water were taken out of the rafts. With the aid of the small motorized punt, which miraculously was still floating, the crew was able to get the white barrels of drinking water out of the ocean. The motorized punt, however, got a piece of hawser in the propeller, so they had to abandon it. The three lifeboats now had to try and reach the mainland of South America by sailing. The castaways, however, did not lack water and possessed plenty of food. The environment in which they were torpedoed had its benefits. Survivors of the ships that were sunk in the North Atlantic and members of the Arctic convoys would have experienced greater hardships due to the intense cold. Of course, it was not a pleasant trip and everyone was tested mentally, but the crew members of the Ombilin were really fortunate. Everyone agreed on staying together, and, accompanied by the soft clinking of lightbulbs, they set a southern course. The next day they learned that staying together was difficult because of the different speed of each lifeboat. It was decided each sloop would continue alone.

The first lifeboat, commanded by Second Mate Visser, was noticed in the night of 18-19 December by the Argentinian tanker Santa Cruz on its way from Buenos Aires to Recife in Brazil. The castaways were taken aboard and looked after well. On the 22nd of December, the Santa Cruz arrived in Recife, and here also the crew members received good care. The seamen were accommodated in hotels and provided with clothes. Via Natal, Northeast Brazil, and Miami they reached San José near San Francisco on 14 January 1942.

On the 22nd of December 1941, the sloop of Third Mate Hanewinckel, who turned out to be the faster sailor, reached the north-coast of Brazil all on its own. The third mate of the Ombilin described their rescue as follows: "We found ourselves in a river with a heavy current; presumably one of the Amazon’s side branches. Discovered some cabins ashore and also a dugout and took around two hours all hands on the oars to make it through the rapids. Set anchor near the dugout. Couldn’t reach the shore by the sloop. The first radio operator (Ter Boo) and I went ashore in a canoe that came to pick us up. We were very kindly received by simple Creole fisherman. We got a cup of real Brazilian coffee which made us blissfully happy and furthermore, as good and as bad as it went, some information in Portuguese." The castaways turned out to have rowed and sailed 750 miles in ten days. The local fishermen guided the Dutch sloop to the city of Amapa where there was an airfield. Via Georgetown in Guyana, Trinidad and Puerto Rico, the twenty-two persons from Hanewinckel’s sloop arrived in New York on the 30th of December by plane.

The third sloop’s crew arrived one hour later in New York. The people on board this lifeboat, under the command of First Mate H.J. Scheffer were picked up by the British mercantile vessel City of Sydney, which sailed under the command of Captain G.V. Harris and was heading from South Africa to Norfolk, on the American east coast in Virginia. The Dutch sailors were received well and taken care of and arrived ten days later at the final destination of the British ship. After being interrogated by the US Navy, they left by train for New York. The entire 79-person crew of the Ombilin survived the sinking of their ship and, after a few weeks’ rest, again worked as crew on a ship to serve the Allied cause.

The fate of Captain Ellens and Chief Engineer Geenenmans was only known to the KPM after the war. Taken captive aboard the Enrico Tazzoli, they were treated well. They both got their own berth in the officers’ messroom and were allowed to move freely on board the submarine. When the submarine surfaced to charge the batteries, both men were allowed to go up and get some fresh air. They even experienced fighting: on 21 December 1942, the British vessel Queen City was torpedoed and on Christmas Day; the Filipino ship Dona Aurora suffered the same fate while sailing under an American flag. Christmas was extensively celebrated aboard the submarine and the merchantmen were fully involved in the festivities.

In January 1943, the Enrico Tazzoli started the journey home. On February 1st, the submarine reached her base in Bordeaux. The captured merchantmen were accommodated in a country house, and five days later they were taken by train to an internment camp in La Spezia, a harbor town in Northern Italy. After some months, they were transferred to a monastery in the Apennines, and after the invasion of Sicily they ended up in Bologna. Here they heard that on the 8th of September Italy had signed a truce. However, this did not mean the end of the sailors’ captivity. The Germans decided to transport the prisoners in cattle cars to Germany. Via Mossberg near Munich, Ellens and Geenemans, together with hundreds of other Allied merchant marine personnel, ended up in a camp near Hamburg. It took until the 28th of April 1945 before they were freed by British troops.

Definitielijst

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

Images

Epilogue

For Captain Ellens and Chief Engineer Geenenmans, the war lasted over three years, during which they were captives for two. They can be seen as the lucky ones, whereas thousands of their merchant marine colleagues lost their lives at sea. This applied to the crew of the Enrico Tazzoli. After the submarine was customized into a transport submarine, she left on the 16th of May, heading for Japan, with 165 tons of goods aboard. The Enrico Tazzoli, however, went missing on the 23rd in the Gulf of Biskaje. After the war the Italian Navy, joined by the British Admiralty and the US Navy, investigated the missing submarine. There was no confirmation of any successful Allied attack on the Enrico Tazzoli. It was only much later that the Royal Navy could report that the American destroyer USS MacKenzie, after sonar contact on the 16th and 22nd of May 1943, while guiding an Allied convoy in the Gulf of Biskaje, had launched two successful depth charge attacks on enemy submarines. The first assault sank the German submarine U-182, and the second would have sunk the Enrico Tazzoli. All crew members from the Italian submarine died.

In February 1943 capitano di corvette Carlo Fecia di Cossato personally was decorated by the German Grossadmiral Karl Dönitz, who was the operational commander of the Italian submarine. Di Cossato was then transferred to be commander on the torpedo boat Alisea. A few months later he became commander of a flotilla of torpedo boats where he successfully fought against German naval assets in the Mediterranean after the Italian truce. He was, however, very angry about his homeland’s defection to the side of the Allies and about the surrender of the Regia Marina. This was clear from the final letter he wrote to his mother. At age thirty-five, he committed suicide in Naples on the 27th of August 1944.

Definitielijst

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Images

The Enrico Tazzoli was probably sunk by an Allied depth charge in May 1943. Source: Navie Armatori.

The Enrico Tazzoli was probably sunk by an Allied depth charge in May 1943. Source: Navie Armatori. Capitano di corvetta Cossato is being decorated by the German Grossadmiral Karl Dönitz. Source: Sommergibili.

Capitano di corvetta Cossato is being decorated by the German Grossadmiral Karl Dönitz. Source: Sommergibili.Information

- Article by:

- Peter Kimenai

- Translated by:

- Joshua Rijsdam

- Published on:

- 17-08-2019

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!