Rise and fall of the Panzerarmee Afrika

North-Africa was a battlefront opened by Adolf Hitler in 1941 after the Italians had suffered a massive defeat in the battle of Beda Fomm against the British, between February 5 and 7, 1941, from their colony Libya on British Egypt. That battle was the finale of Operation Compass, which the British launched on 9 December 1940. The Italians were then further pushed back by the British to El Agheila. As a result, the Allies had advanced 497 miles in two months and had destroyed an army of 10 divisions, made 130,000 men prisoners of war, and captured 180 medium-heavy tanks, 200 light tanks and 845 cannons. The disadvantage of this victory was that Germany became involved in the battle.

Overview North-Africa (top) and the retreat of the Italian army, culminating in the crushing defeat near Beda Fomm (bottom, February 1941). Source: Marcel Kuster

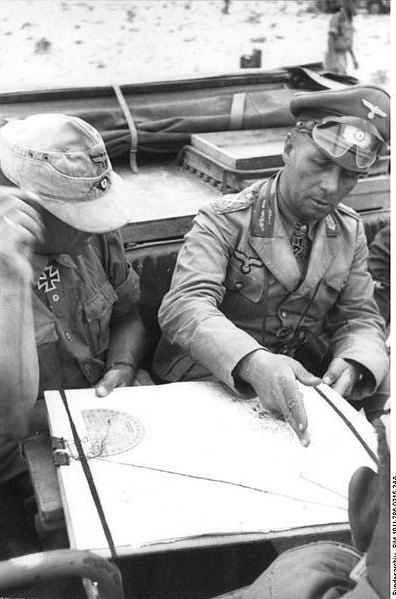

Hitler was far from pleased with this state of affairs among the Italians and ordered Generalleutnant Erwin Rommel on February 6, 1941 in Berlin to take command of a small German unit in North-Africa. The aim of this unit was partly to save the Italian allies from destruction and to prevent the Vichy-French army from joining the British in North-Africa. The choice for Rommel was moreover rejected by a number of officers within the Oberkommando des Heeres. They preferred Generalmajor Hans Freiherr von Funck be appointed to this post, because he had knowledge of the terrain there. However, Hitler disliked Von Funk, because he was a good friend of Generalmajor Werner von Fritsch who had been disgraced in 1938. Incidentally, there are indications that the Deutsches Afrikakorps (DAK) was part of a larger operation, to eventually advance through the Middle East towards the Caucasus. The unit initially consisted of two divisions, the 5. Leichte Division and the 15. Panzer Division (which only arrived in May 1941). In addition, Rommel was given command of two more Italian divisions. Formally, the German commander was subordinate to the Italian general Italo Garibaldi, with whom he later had quite a lot of discussions. In practice Rommel had a direct line with Berlin, the Oberkommando des Heeres and Hitler, so actually he worked a lot with Italians.

The logistical situation was quite complicated for the Afrikakorps, because the British with the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean and the Royal Air Force in Malta, had a great deal of battle power, which allowed them to attack the supply lines rather uninhibitedly. In favour of the Germans, was the underestimation of the British commander General Sir Archibald Wavell, who particularly misjudged the DAK's offensive attitude. What further complicated the long-term situation was the planning and execution of Operation Barbarossa, Germany's massive operation against the Soviet Union. This attack started on June 22, 1941 and would take up many troops and logistical resources, with the result that the DAK was certainly not at the top of the army's list of priorities.

In July 1941 the DAK was reinforced with some Italian units: the 20th Italian motorized and the 21st Italian Infantry Corps, to which the 10th Italian Infantry corps was added later. This can be seen as a reward of Hitler and Mussolini for the successes of Erwin Rommel. In addition, he received permission from Germany to form the 90. Leichte Afrika Division of a few separate German units in North-Africa (which were not part of the aforementioned units). Probably because of the ongoing Operation Barbarossa, in which the Wehrmacht tried to bring the Soviet Union to its knees, Rommel did not receive any further German troops.

Definitielijst

- DAK

- Short for Deutsches Afrikakorps. German expeditionary army, sent out in 1941 to support their Italian allies in their desert war in North Africa.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Continuing logistic challenges

Erwin Rommel became known for his daring way of waging war, in which tanks and speed were enormously important. Because Rommel's tanks often made rapid progress, it was an enormous task in the vast desert landscape to supply these troops. On top of that, in the Mediterranean, there were still many ships of the British Navy, which would certainly not fail to target supply ships of the DAK. The British also owned the island of Malta, and from that island they were able to ensure that Rommel always received less than 60% of his supplies. These two facts meant that the DAK faced considerable logistical challenges. That situation did not change during the entire deployment, not even when the DAK became part of Panzerarmee Afrika. It is so important to emphasise the logistical problems, as they often severely limited the deployment possibilities of troops for commanders. Especially in 1942 this became painfully clear, as can be read below.

Many of Rommel's officers fell ill during the fighting in North-Africa, so many key figures often had to go to Germany for medical treatment. The poor supply of fuel, ammunition and food, which left the troops with too little or bad food, certainly did not help. This was a common thread in the fighting throughout the presence of the Afrikakorps and later the Panzerarmee.

Definitielijst

- DAK

- Short for Deutsches Afrikakorps. German expeditionary army, sent out in 1941 to support their Italian allies in their desert war in North Africa.

Desert war until December 1941

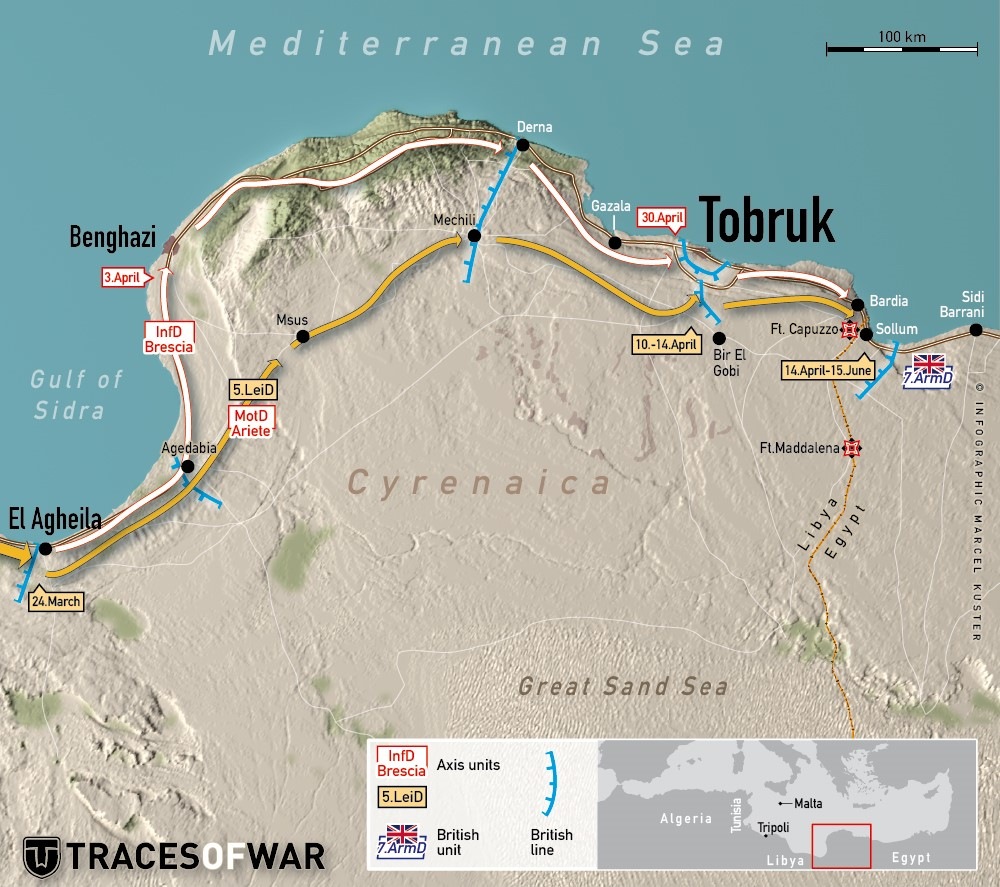

After his arrival, Rommel managed to reorganize the Italian troops and thus stop their flight from the British army. The DAK had orders in February 1941 to postpone operations until the 15. Panzer Division had arrived in full in May 1941. Commander Rommel, however, had overestimated the strength of the British and discovered that the British were actually much weaker. Therefore he decided to attack the city of El Agheila with the Afrikakorps on March 24, 1941 by means of the 5. Leichte Division and did so successfully. Before the DAK was fully deployed in North-Africa, Erwin Rommel continued his advance in early April, as he discovered that the British were retreating. To everyone's amazement he did so successfully, because in March and April of 1941 he and his troops conquered all of Cyrenaica, an area covering all of eastern Libya. All this time he did not have access to 15. Panzer Division, but only the 5. Leichte Division, the Italian Brescia Division (Infantry) and the Ariete Division (Mechanised). The advance only stopped near Sollum at the end of May 1941. Part of the forces from the Afrikakorps was then deployed in the first siege of Tobruk, the port city that the Germans were unable to capture in 1941. The factors in the rapid advance of the Afrikakorps were pure bluff, good communication between different army units and the concentration of the attack on the weaker parts of the British army (such as the lightly armoured infantry vehicles, instead of the British tanks). Rommel also concentrated the DAK on one point to force a decisive breakthrough there and he accomplished this, with the aid of the rather chaotic retreat of the British troops.

Rommel attacked prior to the arrival of 15. Panzerdivision in May 1941 and surprised both friend and foe with his victories. Source: Marcel Kuster

He pulled around fortified positions with his armoured vanguard to attack them from the rear or he had his infantry units deal with them. He usually did not allow his enemies time to regroup. His performance earned him the nickname The Desert Fox. The British certainly had an interest in praising Rommel's achievements in order to explain away their defeats and cover up the failing leadership. Rommel was not always very popular with his subordinates, especially because he cared little about the lives of his men when waging an attack. The commander of the 5. Leichte Division, Generalmajor Heinrich Kirchheim wrote to Generalstabchef, Generaloberst Franz Halder about Rommel in April 1941: "He shuttles all day among his scattered troops, orders them to attack and drives his soldiers through it." On the other hand, he also commanded respect from the ordinary soldiers, because he often stayed at the front and shared their hardships.

Rommel's initial success did not last long, as 10. Luftwaffekorps received orders to move its headquarters to the Balkans, rather than to Sicily. This prevented the Germans from maintaining their grip on Malta and offered the British room to strengthen their air base on Malta. This was so successful that in the second half of 1941 up to 77% of the supplies for Afrikakorps never reached North-Africa. Malta had thus become a serious threat to the survival of the German and Italian troops. On July 21, 1941, Churchill replaced General Archibald Wavell with General Sir Claude Auchinleck. When Operation Crusader was launched under his command on November 18, 1941, the DAK was eventually defeated and driven out of Cyrenaica, partly due to the poor logistical situation. The British supremacy in manpower and equipment certainly played a role in this. Nevertheless, the DAK managed to inflict considerable damage to the attacking British troops in a daring counterattack between November 21 and 27, 1941. The success of that attack around Gabr Saleh and Sidi Rezegh, despite many destroyed British tanks, even caused great headaches to the British commanders (especially General Norrie, commander of the 30th Army Corps), who desperately withdrew troops. The Afrikakorps came within a hair’s breadth of turning the Crusader tide against the British. However, the Allies recovered, aided by British supplies not having been discovered by the Afrikakorps and good leadership by General Auchinleck, and pushed back the German-Italian troops. Around the turn of the year, Rommel and his troops were back to square one.

Definitielijst

- DAK

- Short for Deutsches Afrikakorps. German expeditionary army, sent out in 1941 to support their Italian allies in their desert war in North Africa.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Tobruk

- Small bunker. Usually manned by one soldier with a machinegun, but there were also bigger tobruks equipped with a canon or mortar.

Rommel's counterattack towards the Gazala line

- Afrikakorps: 21. Panzerdivision, 15. Panzerdivision.

- 90. Leichte Motorisierte Division.

- XX Italienische Motorisiertes Korps: Ariete Division, Trieste Division.

- XXI Italienische Infanteriekorps: Pavia Division,Trento Division, Sabratha Division.

- X Italienische Infanteriekorps: Bologna Division, Brescia Division.

In January 1942, Rommel launched a new offensive, partly in order not to have his base and seaport Tripoli in Libya taken away by the British. In view of the British having very long supply lines because of their victory in the Cyrenaica, it was Rommel’s motivation for taking advantage of this opportunity. In addition, the Germans were able to intercept and decipher messages from the American military attaché Colonel Bonner Fellers, after Italian agents had stolen a codebook from the American embassy. Rommel could use that information to see exactly what the status of his British opponent was. In order to complete the picture, the Panzeramee itself had also gathered intelligence (intercepted radio traffic from the 8th Army) about his opponent and this clearly showed that the British were not well positioned.

Based on all this information, an attack was planned on January 21, 1942 to drive the British back. The plans of this attack were kept secret from everyone except for a select group of officers. Also the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW), which the Panzerarmee was part of since December 1941, knew nothing of the attack. This was because of the Italians who previously leaked information to the British in 1941 (caused by the infiltration of secret agents into the highest Italian military command). Also the OKW had occasionally leaked information to the Italians, who in turn passed on that information to the British. Rommel even decided to tell them lies, which put the opponent on the wrong foot once the attack actually started. Keeping the attack secret really came as a surprise. When the tanks of Panzerarmee Afrika began to roll, they completely surprised the British.

After Operation Crusader, in which they expelled the Afrikakorps from Cyrenaica again, the British did not expect their opponent to counterattack again so quickly. The British troops were scattered all over Eastern Libya, making it impossible for them to fight the German-Italian troops. Moreover, the troops were also in a bad state. The 7th Armoured Division stayed in Cairo for maintenance and was replaced by the inexperienced 1st Armoured Division. Other experienced units, such as the Australians who had stubbornly and heroically resisted the previous year in the Libyan port city of Tobruk, had been transferred to the Far East where Japan had gone on the offensive in December 1941. Lieutenant General Sir Neil Ritchie was commander of the British 8th Army and had a fairly successful military career, but mainly as a staff officer. As commander of a unit, Ritchie had very little experience and that cost him dearly when Panzerarmee Afrika attacked on January 21, 1942. Ritchie ignored advice from his veterans to withdraw, causing the 1st Armoured Brigade to be annihilated.

The German-Italian force pushed forward and headed for Benghazi, the main prize of this attack, on January 29, 1942, and managed to capture the city, partly through deception of Ritchie's command. It did not stop there, because the British retreated to the so-called Gazala line. Panzerarmee Afrika chased the British to that line and could not attack any further after that, which stopped the operation. It was a great success, because the British were completely surprised and were again driven out of the Cyrenaica with heavy losses. After this attack there was a period of relative calm for the ground troops on both sides in North-Africa. This period lasted until May 26, 1942, but it did not apply to logistical, air and sea troops who fought unabatedly for influence in the Mediterranean.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- infiltration

- Quiet incursion into enemy lines prior to an attack.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- Tobruk

- Small bunker. Usually manned by one soldier with a machinegun, but there were also bigger tobruks equipped with a canon or mortar.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Advancing to Tobruk

In the first half of 1942, the supply of Rommel's troops did not improve, but apart from the numerical minority in tanks, the technological backlog now also needed to be considered. In 1942, the British were able to introduce the M3 Grant tank from the US. These tanks, with their 75mm gun, were superior to the German PzKpfw III tanks, which were armed with 50mm guns. The Eastern Front was given priority by Nazi Germany, and that started to be a problem in North-Africa. In addition, the British were still able to disrupt the German supply routes.

In the calmer period for the land armies, the British constructed what was known as the Gazala- Line. An originally Italian defensive line in Libya that was fortified by the British. Extensive minefields were created and reserve troops and supplies were provided behind the defense line. The British had superiority in manpower and technique at that time.

With a lot of bragging, Rommel decided to launch an attack. He did so on the May 26. Panzerarmee Afrika attacked the Gazala Line (Italian 10th and 11th Army) with a part of infantry units, while Rommel in personal command, with the Afrikakorps (15.Panzerdivision, 21. Panzerdivision, 90. Motorisierte Division, joined by the Italian Ariete motorized division) pulled around the line and attacked the British in the rear. Because the British were superior in men and equipment and because of incomplete information on Rommel's side, this attack almost meant the end for the German-Italian troops. Because of poorly coordinated British attacks, which caused a lot of damage, Rommel and his army were able to fight on, but the fate of the troops on the German side was hanging by a thread. If the British attacks had been better coordinated, the Panzerarmee's complete Afrikakorps would have been decisively defeated. On June 4, there was a break in the fighting, which lasted until the British wanted to carry out another counter-attack.

During the attack described above, a unique situation arose, certainly by German standards. The deputy commander of Panzerarmee Afrika, General der Panzertruppe Ludwig Crüwell, went missing when, during an inspection flight in a Fieseler Fi 156 Storch on May 29, 1942, towards the frontline, he strayed way of off course and ended up on British territory. Crüwell was captured and the war was over for him. That was a huge loss for the headquarters of Erwin Rommel, who was also at the front. Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring happened to be visiting the headquarters of the Panzerarmee and Major Friedrich Wilhelm von Mellenthin, one of the staff officers, asked if Kesselring was willing to temporarily take over Crüwell's command. There was a real danger that the Italians would otherwise start a mutiny. Kesselring accepted with a certain reluctance, causing a Generalfeldmarschall (Kesselring) to temporarily subordinate himself to a Generaloberst (Rommel).

Rommel’s advance towards Tobruk (top, January-June 1942) and the attack of the Panzerarmee near Gazala (bottom, end of May/beginning of June 1942), inflicting a defeat on the British. Source: Marcel Kuster

The counterattack by the British followed on June 5, but lacked conviction, preventing them from breaking through the lines of the German-Italian troops. In addition, the Germans and Italians had cleared large parts of the minefield laid by the British. This had created much more room for maneuver. The British counter-attack was repelled and the Germans maintained their positions. Rommel and his army also wanted to conquer the city of Bir Hacheim, because it was a potential danger to their positions. On 8 June, Bir Hacheim fell into the hands of the Panzerarmee, despite fierce resistance from the French 1ère Brigade (Free Frenchmen) under the command of Général Marie-Pierre Kœnig. Rommel was thus able to consolidate his position on the battlefield.

A final offensive was launched on June 11, the aim of which was to break the British force. The British still had numerical superiority in tanks and men. However, the Germans managed to intercept a British radio signal with marching orders, so they knew exactly what the British were planning. Rommels troops maneuvered the British opponent into an ambush, causing the British to lose half of their tanks and the Panzerarmee to have won this battle decisively.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- mutiny

- Revolt of soldiers or sailors against the authorities.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Capture of Tobruk

The next target came in sight, the city of Tobruk, where the year before Rommel had not been able to break the resistance because of exhausted troops and a dramatic logistical situation. Before Rommel could advance to Tobruk, the British first had to be driven out of their positions on the Gazala line. Because of the victory in Bir Hacheim and the decimation of the British strike capability, the troops of the Panzerarmee were able to do so quite easily and march along the coast to Tobruk, chasing the British.

Panzerarmee Afrika then controlled the area to the west and south of Tobruk, so now they were also trying to control the eastern area to completely encircle the city. For this reason Rommel and his troops had to capture the city of Gambut, a city east of Tobruk. This was achieved on June 17, when the British 4th Armored Brigade was defeated and they retreated with the German 90. Leichte Motorisierte Division on their heels. The encirclement of Tobruk was a fact.

The German baseline was not bad around Tobruk. The city was defended by an insufficient number of troops, who struggled with low morale and the defenses were in poor condition. The cause was the construction of the Gazala-line, for which material from Tobruk was used (among other things mines were reused). The attack started with a large aerial bombardment, after which a diversionary attack was launched from the southwest towards Tobruk. The main attack was carried out by the Afrikakorps (the two German armored divisions), who had to outsmart the British 32nd Tank Brigade. The British had already lost considerable striking power because of earlier losses and now the troops of the Afrikakorps only needed an hour to completely destroy the brigade. Panzerarmee Afrika drew closer and closer to the city.

An English built Mark II Mathilda tank, captured by the Germans near Tobruk. Source: Wikimedia Commons

After the destruction of the British 32nd Tank Brigade, the resistance in the city was quickly breached and Rommel managed to completely take over Tobruk on June 21, 1942. The garrison commander, the inexperienced South African Major General Hendrik Klopper, surrendered the city while the port facilities had not yet been destroyed, so that they fell into German hands intact along with large quantities of British oil, food and equipment. This surrender resulted in 19,000 British, 2,500 Indian and 10,500 South African soldiers in German captivity. The fall of Tobruk heralded the end of a long string of defeats that the British suffered against the Germans. Panzerarmee Afrika had an incredibly high morale because of the victories and that certainly contributed to the good performance on the battlefield. Rommel knew the terrain very well because of the battles a year earlier, better than his British opponent. The British were also short of anti-tank armament and faced an failing leadership, unable to organize serious resistance. After the victory, Rommel was promoted to Generalfeldmarschall, the youngest in the German army at the time. He himself, would have much preferred to receive reinforcements to give shape to the continuation of this success.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Tobruk

- Small bunker. Usually manned by one soldier with a machinegun, but there were also bigger tobruks equipped with a canon or mortar.

Advancing to Egypt

After the fall of Tobruk, permission was requested to invade Egypt, the next target. Even though no real reinforcements were received, Rommel hoped to achieve this with 2,000 captured British vehicles. This was a momentum he did not want to lose. He was the only one who was convinced of possible success, because both the German and Italian army leaders thought it was a particularly bad plan. Malta was still in British hands, which made it difficult to assist the attack with German air support. Yet Rommel got permission, because Hitler was on his side.

The logistics did not improve after the capture of the port city of Tobruk, because the Italian Navy hardly used the newly acquired port. They preferred to sail to Tripoli or Benghazi, because those ports were closer to Italy. Rommel`s logistical problems were made even more difficult by the Italian navy, because everything still had to be transported by land for at least 715 miles. On top of that, the Italian Army faced a huge shortage of motorized transport and the fuel and food rations they provided were often of poor quality. When the British gained complete air superiority in mid-1942, that lifeline was very vunerable for Panzerarmee Afrika.

The responsibility of the supplies lay with the Italian supreme command in Rome, but this body was certainly not fond of Rommel and German interference in North-Africa. Rommel owed this partly to himself, because he could behave rather arrogantly. As a result, they often allocated much more supplies to Italian units, resulting in the German units receiving far less than what they needed, sometimes up to 70% less. When Rommel repelled many British attacks in July 1942, about a hundred German tanks waited in Italian ports for transport. On the proposal to make Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring responsible for the logistical situation of Panzerarmee Afrika, Rome reacted furiously and rejected the idea.

Only one day's rest was given to the troops of Panzerarmee Afrika, after which they received Rommel's marching orders to attack and defeat the British 8th Army. The first target was Mersa Matruh, a town about 140 miles east of Tobruk. That was also the next place the British had fallen back on. There was a great danger for Rommel and the Panzerarmee during this attack, as the whole road to Mersa Matruh was open allowing the R.A.F. and specifically the Desert Air Force to attack the German troops and Malta was also still in British hands, thereby minimizing German air support. This scenario unfolded on June 23, when Rommel's troops went on the attack. They gained ground and chased the British back, but at the same time they were mercilessly attacked by the R.A.F. from the air. By June 25, the Panzerarmee troops had reached a position 31 miles east of Mersa Matruh and were in Egypt. However, the Germans and Italians were severely battered, for example, there were only 42 operational tanks left in the Afrikakorps, which was still the nucleus of Rommel's army.

The rapid advance was undoubtedly clever, but it also cost Panzerarmee Afrika dearly. Morale was high because of the advance, despite the overdue maintenance of the equipment and the lack of supplies. Meanwhile, while the position at Mersa Matruh had been reached, the R.A.F.'s air raids continued without losing any intensity.

Within a few days, on June 28, troops of the Afrikakorps and the 90. Leichte Motorisierte Division had also seized Mersa Matruh. The troops then began chasing the British towards Alexandria. They drove mainly in captured British vehicles and on British fuel. The original German or Italian equipment was almost exhausted. The men were exhausted, some of them had hardly slept for 4 days, but the excellent morale allowed them to continue. The British had built up a new line of defense at El Alamein. The advantage of this position was that it could only be attacked from the front, because it was flanked by the sea on one side and the Qattara Depression (a salt marsh characterized by quicksand) on the other side. Here the advance of Panzerarmee Afrika was stopped by heavy artillery fire and the still constant RAF bombardments. In addition, an acute shortage of tanks and other armored vehicles certainly played a major role. After this attack, the fearsome Afrikakorps still had about fifteen tanks left. Whatever Rommel was planning, Panzerarmee Afrika had lost its striking power. With this, the dream of reaching Cairo was gone once and for all. The ball was now in the British court.

Definitielijst

- El Alamein

- City in North Egypt. The Battle of El Alamein took place from October to November 1942 and was a turning point in the war. The German-Italian advance in North Africa was finally halted by the Allies.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- Tobruk

- Small bunker. Usually manned by one soldier with a machinegun, but there were also bigger tobruks equipped with a canon or mortar.

The situation at El Alamein

When Rommel prepared his first attack on El Alamein on August 30, 1942, he had so few supplies that his tanks could only drive 75 miles each. When Kesselring claimed that he could guarantee the necessary fuel by air, Rommel was able to continue his attack. By comparison, Panzerarmee Afrika received 17,000 tons of supplies at the end of August, while the British were able to add 500,000 tons of supplies. In addition, the land supply lines of the Panzerarmee were extremely long, which meant that the little amount could also be attacked by the Desert Air Force.

Thanks to a large number of excavated British landmines, supplemented with variants of German manufacture, Rommel was able to set up reasonably good defensive positions. This enabled him to repel a first counter-attack by General Auchinleck between July 5 and 9, 1942. After this, Rommel decided to attack again with his army, but had to postpone those plans when all members of his intelligence company were killed or captured during an attack by the troops of the 2nd New Zealand Division on July 10. Among others, his main intelligence officer Kapitän Alfred Seebohm was killed in this attack. The Panzerarmee would not recover from this blow. With Seebohm's death, the British also managed to capture his notes. This was a heavy loss for Rommel. Before that, thanks to his good intelligence, he had always had an accurate picture of the enemy positions and forces. Now he had to determine his tactics without that advantage. In addition, at the insistence of the British, the Americans changed the codes for the military attaché, as a result of which this source of information was lost also.

After that, the remnants of Panzerarmee Afrikca still did not take offensive action, because Auchinleck had planned his next attack. The British did not gain any ground, but created an even more precarious situation with the ammunition supply on the German-Italian side. The position of the British 8th Army at El Alamein could only be attacked head-on and Rommel decided to take that risk, but his attack failed. Meanwhile, Auchinleck realized that many of the Italian units of the Panzerarmee surrendered considerably faster than their German colleagues and allowed themselves to be taken as prisoners of war. Therefore, he attacked mainly the Italian sectors successfully and the German units of the army served as a kind of fire brigade behind the front. General Auchinleck launched a total of ten offensives with the 8th Army against the Panzerarmee in July 1942 and they all failed. Despite the fact that the German-Italian troops were in poor condition, they still had enough strength to maintain their positions and to repel the British time and again. Towards the end of July 1942, there was a short pause in combat, in which both sides prepared for what was to come.

In the meantime, the British in North-Africa managed to achieve superiority in the air. That was a very important fact, because it would further worsen Rommel's logistics situation and make troop movements much more complex. In addition, his health deteriorated due to the brutal conditions and the enormous exhaustion of the first half of 1942, and he was one of the many soldiers who fell ill. Yet they continued. Rommel actually had to return to Germany for medical treatment, but when his own choice as replacement Generaloberst Heinz Guderian was refused him, the Desert Fox stayed in North-Africa.

In the meantime, the 8th Army got a new commander, Lieutenant General Bernard Montgomery. In addition, General Auchinleck was replaced by General Sir Harold Alexander as Commander-in-Chief Middle East. The first thing Montgomery did was make sure all small attacks stopped, because he wanted to attack, in a concentrated way and with great force. something Auchinleck would have wanted at an earlier stage as well.

Definitielijst

- brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- El Alamein

- City in North Egypt. The Battle of El Alamein took place from October to November 1942 and was a turning point in the war. The German-Italian advance in North Africa was finally halted by the Allies.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

Rommel's attack on El Alamein

Rommel had planned an attack with his troops on August 30, 1942. At the start, the British had three times more tanks and five times more planes at their disposal. In addition, Rommel was totally dependent on the supply of new fuel to keep his tanks running. Kesselring's promise to take care of this by air was honoured, only the fuel still had to be transported to the front. There, valuable time was lost that the Panzerarmee did not have.

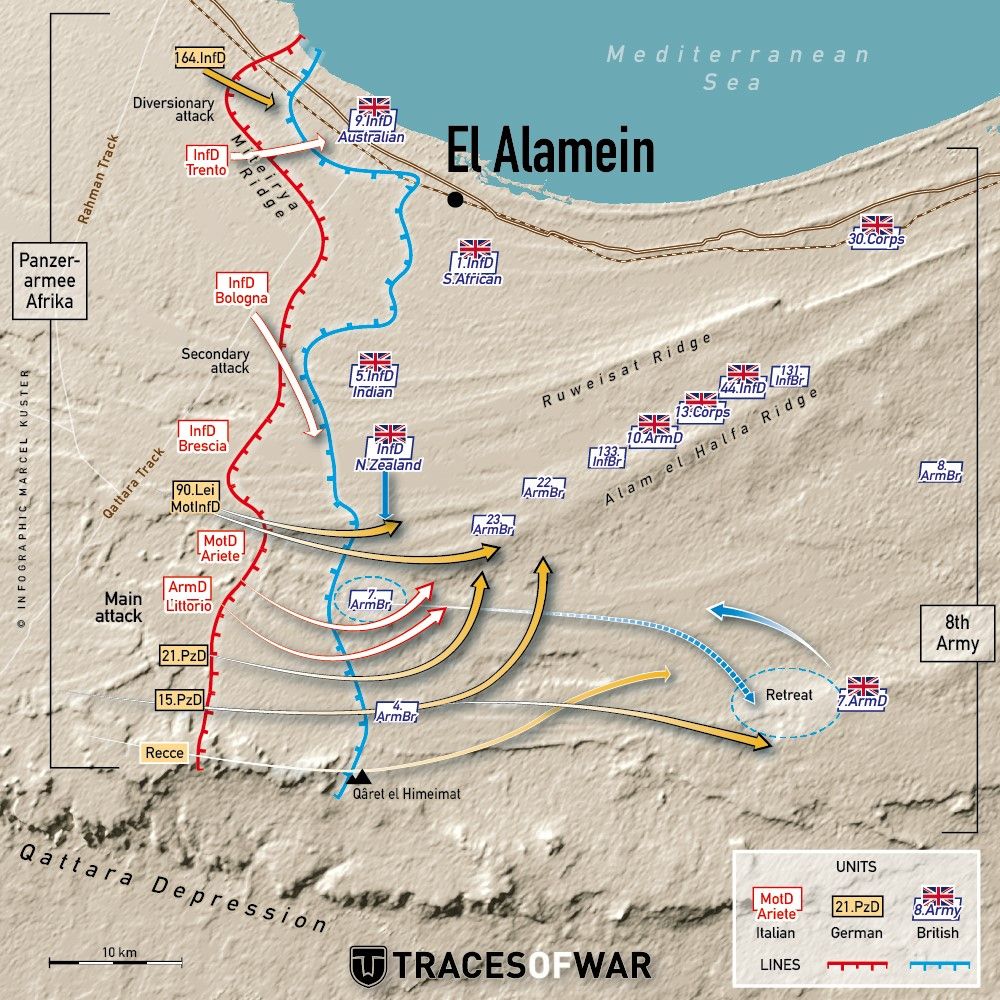

Rommel’s attack at El Alamein (August-September 1942), near Alam el Halfa. Note the deployment of the British rear guard (in line and in depth), where the attack was expected. In addition, the British had sown gigantic minefields making any movement impossible. Source: Marcel Kuster

Yet the attack continued and its success depended entirely on speed. However, there were two flaws in the attack plan: there was the severe fuel shortage described above and it was the same tactic that Rommel had already used in the North-African desert, so the element of surprise was lost completely

In addition, the British had discovered the plans for the attack because they had cracked the German Enigma code, which enabled them to decode a large part of German communications. Montgomery knew exactly what was to happen and set up his defensive plans accordingly with a large linear mechanized reserve. This reserve had to stop Rommel's encirclement at Alam el Halfa. The Afrikakorps, which so often had to form the force of the attack, was again the most important punching weapon. Only the troops were soon stranded in a huge minefield and were easily battered by the British, because they had nowhere to go. They gained ground, but at the cost of many soldiers' lives and fuel, which was already in short supply.

The next day, the Panzermee continued to attack the Alam el Halfa defence line, where the British had skilfully dug themselves in. At the same time, the bombardments continued, thanks to British air superiority. Rommel was therefore forced to withdraw his troops on September 2. While the Italians and Germans were doing this, the RAF remained active, causing considerable losses in equipment and men. The total losses of the British and the Axis powers were similar, but the difference was that Rommel could not make up for the losses.

At the same time the battle of Alam el Halfa was lost by the Panzerarmee, the British had also achieved superiority in the air and on the Mediterranean Sea. In addition, the U.S. Air Force had also appeared on the scene. Because of this, the prospects were quite poor for the Panzerarmee Afrika. Rommel realized that his last chance to reach the Suez Canal was lost. The tide had definitely turned, now to the disadvantage of the Axis Powers. After the lost battle, a pause in combat occurred, as Montgomery decided to maximize his equipment dominance, to the point where he was sure he could defeat Panzerarmee Afrika. In practice, this meant that there were many pauses between the various British attacks.

Definitielijst

- Enigma

- Cryptographic (de)coding machine used by the Germans during World War 2. The code was broken by the British with help from the Poles. Much German military information was known to the British in advance. This was a huge aid to the war effort.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

Developments during the lull at El Alamein

At El Alamein it became really clear how bad the supply of Panzerarmee Afrika had always been. The victories over the British up to this point meant that the Germans were able to make extensive use of British equipment and related supplies, but their own equipment and stock became increasingly scarce. On the British side, the supplies continued to improve, helped by shorter supply lines. This allowed the tide to turn against the troops of Rommel.

The superiority of the other side, on the other hand, had simply become too great, and the massive need for German troop deployment in the Soviet Union could not possibly change that, as no new German units were available.

Rommel got some reinforcements during the battles at El Alamein after repeated insistence, especially in the form of infantry divisions (one German and three Italian).

Meanwhile, his troops on the battlefield were in very bad shape. In the Afrikakorps there were only a few dozen medium tanks available and a few dozen tanks in poor condition or of an inferior type. With the Italians, the situation was no better. They still had several hundred light tanks that were completely unsuitable for such battles. In addition, the artillery had only two rounds per gun. Panzerarmee Afrika therefore made good use of British weapons and ammunition, but that did not alter the fact that the overall situation was downright lousy.

Hitler did not allow the German and Italian troops to retreat, whatever the circumstances. But even if they had wanted to, this would not have been possible because of a shortage of fuel. Montgomery's first real pinprick was an attempt to capture Tobruk with the Long Range Desert Group in combination with the Royal Navy. That action failed miserably: the Royal Navy lost four destroyers and a few escort ships and the Long Range Desert Group was all but annihilated.

At Alamein, Panzerarmee Afrika began to build a defence line near Alam el Halfa, the point where they had been stopped earlier by the 8th army. Use was made of the existing British minefields behind which anti-tank artillery and anti-aircraft guns were placed. The situation for the troops of Rommel was mediocre, as they had received a maximum of 40% of their supplies for eight months. Troops lived on a minimum of food and water and vehicles had a minimum of fuel.

In mid-September 1942, Rommel went via Italy to Germany to get medical treatment, because he had stomach ulcers, high blood pressure and liver problems. At the same time, he was summoned by Hitler to explain the North-African situation, and Rommel noticed that there was a false optimism about the situation in Germany and the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) did not realize how serious the situation was. All kinds of promises were made that could hardly be kept. At the same time, new commanders were appointed at Panzerarmee Afrika. All of them were highly respected officers, who finally solved the lousy situation of officers dropping out, but this did not help Rommel enough. In September 1942, while still recovering and in his absence, General der Panzertruppen Georg Stumme had taken command of the Panzerarmee.

Definitielijst

- El Alamein

- City in North Egypt. The Battle of El Alamein took place from October to November 1942 and was a turning point in the war. The German-Italian advance in North Africa was finally halted by the Allies.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Tobruk

- Small bunker. Usually manned by one soldier with a machinegun, but there were also bigger tobruks equipped with a canon or mortar.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

First massive attack by the British

On October 9, 1942, the fighting continued and the British intensified their bombing of Panzerarmee Afrika. The targets of these bombardments were stock depots, airports and harbours. The air raids heralded an attack against the German armoured troops, in which they had no choice but to dig themselves in and hope for the best. The lack of fuel nipped any other ambition in the bud. However, for better or for worse, the previously mentioned defence line was built. In spite of optimism on the part of the Panzerarmee, they were so outnumbered that the outcome of the coming battle was a foregone conclusion.

On October 23, 1942, the British ground attack on the German-Italian positions started with enormous superiority. It started with an artillery barrage by 1200 guns that lasted five hours. Consequently, parts of the siege's defence line and lines of communication were severely damaged. Bernard Montgomery attacked in the northern sector because the defence lines were strongest there. He therefore assumed that the Germans would never expect an attack here. To reinforce this impression, he organised a diversionary tactic, which had to show that the attack would take place further south. However, the effect of this was minimal. Contrary to what Montgomery hoped, the Germans and Italians sent only few troops to the southern sector. Moreover, the course of the British offensive gave them the opportunity to regroup their troops in the north in order to deal with the attack. Although the initial attack by the ground forces was met with a great deal of resistance and the gains were not as rapid as Montgomery had expected, their superiority and the tactics of continuous attack ultimately won the day. On October 24, 1942, General der Panzertruppen Georg Stumme was killed in an attack, causing the Chef des Stabes of the Panzerarmee, to ask Rommel to return early from his recovery period.

The moment Rommel returned, he found that the troops had not only been hit hard by the British, but also by disease due to malnutrition caused by the lack of supplies. In addition, the fuel supplies had run out, so Rommel had to move heaven and earth to do something about it. The numerical superiority of the British on the ground and in the air slowly began to take its toll. The attacks continued unabated and the Panzerarmee managed to launch a number of counter-attacks despite its terrible status. However, they were not a success and the lack of fuel began to determine the strategy.

On October 29, 1942, there was finally a short break for the German-Italian troops. During this break, the headquarters was visited by the Italian logistics officer who was responsible for the supply of stocks. He was severely brow-beaten and finally seemed to see the seriousness of the situation and also at the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) the optimism started to evaporate (until then, it had been believed that the Panzerarmee would hold out). The next day Rommel actually received 600 tons of fuel, which slightly improved the condition of his army.

Definitielijst

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Operation Supercharge and retreat of the Desert Fox

The situation was still difficult and Panzerarmee Afrika soon had to endure another attack from the British: Operation Supercharge. It began on November 1, 1942, with a large number of bombing raids by the RAF on the German-Italian positions. Then in the night of November 2, the attack was launched by the British with approximately 800 tanks. Rommel was only able to counter this with 90 German tanks, complemented by several dozen previously captured British tanks and 140 Italian light tanks, which were inferior to the Allied tanks. On top of that, the Panzerarmee was still struggling with a huge shortage of ammunition. These factors made operation Supercharge ultimately a success, although the German armoured troops still managed to inflict great losses on the British with the tanks they still had.

The British 8th army managed to make a breach in the front and it could not be closed. The 15. Panzerdivision of the Afrikakorps tried to do this, but all its tanks were destroyed and also very little remained of the other equipment. The 21. Panzerdivision was now effectively the only battle-ready unit in the Afrikakorps and similarly they had only 35 operational tanks left. Despite this, General der Panzertruppen Wilhelm Ritter von Thoma, commander of the Afrikakorps) succeeded in restoring the front line, even though this front line was insubstantial. At the end of the day, operation Supercharge did not have the destructive effect that Montgomery initially expected.

Erwin Rommel realized on November 3, 1942, that it was time to withdraw. He simply had nothing left to defend with. The troops on the flanks, the Italian and German infantry, were the first to act. They had to manually tow back their guns and repair them without the British noticing the retreat immediately. The British discovered the retreat only the day after, whereupon the German-Italian troops were bombed by the Desert Air Force. Despite the bad situation of the Panzerarmee, they had offered formidable resistance against the British during operation Supercharge and inflicted high losses on them. The British lost approximately 13,500 men and 500 tanks. The Germans and Italians lost 5,000 soldiers and approximately 200 tanks. In addition, the British took about 30,000 German and Italian prisoners of war. The heavy losses prevented Montgomery from continuing his attack on November 3.

It was at this moment that Rommel received an order from Hitler not to budge an inch. Rommel, who had taken an oath, ordered the withdrawal to be terminated. But less than 24 hours later, his conscience bothered him and he decided not to obey Hitler's order. Meanwhile, his troops were in very poor condition and the commander of the Afrikakorps, Von Thoma, was taken prison by the British. In addition, no fewer than six Italian generals were captured due to the delayed retreat.

On November 4, 1942 the retreat really started. Rommel ordered his troops to retreat to the positions near Fuka. On the way they were chased by Montgomery's troops, but still the Panzerarmee managed to stay out of the hands of the British, partly because Montgomery hesitated too much in the pursuit. When the German-Italian armies arrived at the position at Fuka, they were attacked by a superior number of British armoured vehicles, forcing Rommel to retreat further. In doing so, he was forced to leave behind the 10th Italian Infantry Corps, which was still too far away to join the retreat. The next line was Mersa Matruh and on the way there, the 21 Panzer division ran out of fuel and couldn't go any further. After miraculously repelling British attacks, they had to blow up all the jammed tanks and leave them behind. This meant that Panzerarmee Afrika had only 4 operational tanks left when they reached the positions at Mersa Matruh on November 6. 1942.

What happened next was pure luck as tropical rains slowed down the British advance and in some cases even interrupted it. This gave the troops of the Panzerarmee a little breathing space to reorganise. In addition, they received a small amount of fuel, enough to get the armoured divisions of the Afrikakorps moving again. At the same time, 600 men from the Ramcke Fallschirmbrigade appeared which had escaped from El Alamein and were able to rejoin Rommel's troops at Mersa Matruh.The British didn't let the Germans and Italians enjoy that pleasant surprise for long, because they attacked again quickly. However, the Panzerarmee always managed to outsmart the opponent, helped by German sappers who destroyed the infrastructure and used booby traps in order to slow down the British advance. This way Rommel managed to withdraw his troops just in time and prevent worse. At the same time, Montgomery was overcautious and did not exploit small successes to the utmost.

Definitielijst

- El Alamein

- City in North Egypt. The Battle of El Alamein took place from October to November 1942 and was a turning point in the war. The German-Italian advance in North Africa was finally halted by the Allies.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Two fronts in North-Africa from November 1942 onwards

At the same time, on November 8, 1942, a new army came ashore on the West African coast, an American-British army led by Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Forces Mediterranean Dwight Eisenhower. This turned the North-African theatre into a two-front war for Rommel. The American-British operation was called Torch, the landing of the troops on the Moroccan and Tunisian coast and the taking of Casablanca. This was a resounding success, because the Vichy-French troops in Morocco offered little resistance. They were taken prisoner of war or joined the Allies (support for the Germans was very low among Vichy-French troops). Now their next goal was to create a bridgehead in Tunisia to enclose the Panzerarmee Afrika from two sides. Rommel advised Hitler to withdraw all troops to the southern French and southern Italian coast, but Hitler ordered Rommel to stand firm.

In Tunisia new German troops were brought in to repel the attack. A paratrooper regiment led by Oberstleutnant Walter Koch tried to disrupt the Allied operation in Tunis, the capital. This barely succeeded, mainly helped by the tropical rainstorms. Tunisia had no paved roads yet, so the American-British vehicles quickly got stuck in the mud. In addition, the supply lines of this new force ran through the Atlantic Ocean, where the German submarines were still very active. This caused Eisenhower to quickly get headaches about German submarines that were seriously affecting its supply. On top of that, the Luftwaffe managed to gain air superiority over Tunisia, enabling them to bomb the American-British troops. Incidentally, it is important to mention that the Germans had built up much more war experience over the years and this success was largely due to that. The American-British troops on the African west coast were in fact raw recruits and therefore inexperienced

General der Panzertruppen Walter Nehring came to Tunisia on November 16, 1942 to lead the understrength 90. Armeekorps. With this unit he had to prevent the Allies from gaining a foothold in Tunisia. Earlier in 1942, he had also been commander of the Afrikakorps briefly. On November 20, 1942, the American-British troops tried to conquer Medjez el Bab with an overwhelming superiority. Initially this seemed to succeed, because only Walter Koch's regiment defended that position and could only hold out after the 90. Armeekorps, with their 88 mm Flak guns came to the rescue. In addition, a second parachute regiment was flown in: the Barenthin Fallschirmregiment. The Germans managed to consolidate their position and made a small amphibious landing between November 26 and 29, 1942, as well as a landing with paratroopers in the hinterland. Around this time, most of the new 10. Panzer-Division also arrived, under Generalleutnant Wolfgang Fischer, a very experienced tank division that had been active since the invasion of Poland in 1939. In addition, this unit had the latest PzKpfw VI Tiger I, a state-of-the-art tank with a formidable 88mm gun, unparalleled on the North-African battlefield.

Fischer immediately asserted himself by carrying out a counterattack, heavily targeting the poorly coordinated American-British troops with his new tanks. He then managed to take up a new position at Djebel el Ahmera, and thereby gained ground on the Allies. This success brought peace on the North-African battlefield, because Panzerarmee Afrika did not have to reckon with into account an attack in the back.

Definitielijst

- Flak

- Flieger-/Flugabwehrkanone. German anti-aircraft guns.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- paratroopers

- Airborne Division. Military specialized in parachute landings.

- regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- two-front war

- State that occurs when a country is forced to fight a war on more than one border or different areas. During both wars, the First and second, Germany had to deal with a Western and an Eastern Front. During the World War 2 Germany even faced a third front, the Southern front, including the Mediterranean and North Africa.

Retreat from Cyrenaica to Tunisia

At the end of the first week of November 1942, he issued orders to withdraw the entire Panzerarmee to the Gazala line, but after this was successful, large British troop movements were discovered that could endanger the survival of the whole Rommel force. Partly for this reason, Rommel ordered his troops to evacuate the entire Cyrenaica and eventually fall back to a defensive line at El Agheila, because otherwise his troops would face inevitable destruction.

On November 15 and 16, 1942, during the retreat from the Cyrenaica, the Panzerarmee's troops ran out of fuel. Despite the fact that they were trapped like rats and that the 8th army could easily have sealed their fate, this final judgement was not forthcoming. On November 17, some fuel supplies reached Rommel's troops, allowing them to continue the retreat. Benghazi was evacuated and port installations were blown up, after which Panzerarmee Afrika was able to retreat to the defence line at El Agheila. On their way there, the army ran out of fuel again, and every vehicle was sent to the port of Tripoli to get fuel. Because Montgomery actually went to war far too cautiously, Rommel managed to get the fuel to his troops with the previously deployed vehicles. After this, the entire Panzerarmee could retreat behind the defence line at El Agheila which would give them some time and air for a possible British attack. With this, the Panzerarmee had crossed the Cyrenaica earlier than the British in a lucky yet skillful way, thereby rescuing an army that would otherwise have been slaughtered by the British.

However, the situation was still very bad and Rommel calculated that from his once mighty Panzerarmee. in the best situation, he still had an almost complete division left. Yet his superiors were convinced that El Agheila had to be held. Rommel was furious and personally flew to Hitler, because he believed that the Italians presented the dictator with far too optimistic images. However, his arguments fell on Hitler's deaf ears and he was not allowed to withdraw. He did receive promises that supplies would finally be delivered, but these turned out to be empty promises. Now Rommel's troops had nothing to fall back on, no new troops to absorb losses, or supplies to make the difficult material situation a little better.

The once mighty Panzerarmee Afrika with its formidable punching weapon the Afrikakorps had become an empty shell. Repeated requests to retreat to mainland Europe were ignored and the fate of this unit was actually sealed. Montgomery continued to pursue the German-Italian unit, but time after time failed to defeat it. Because Rommel took little notice of the orders to hold out, the Panzerarmee was always able to stay out of the clutches of the British 8th Army just in time. The retreat from the positions near Agedabia is very striking, better known as the Battle of El Agheila. Rommel discovered concentrations of troops south of the Panzermee and could not afford a counterattack with the state of his armies. He decided to withdraw on December 12, 1942, to the Buerat position, about 217 miles west of El Agheila. He managed to hold that position until January 1943, mainly because the troops of the 8th Army were hindered by overstretched supply lines due to the rapid withdrawal of the Panzermee. It was not until January 23 that the British attacked again.

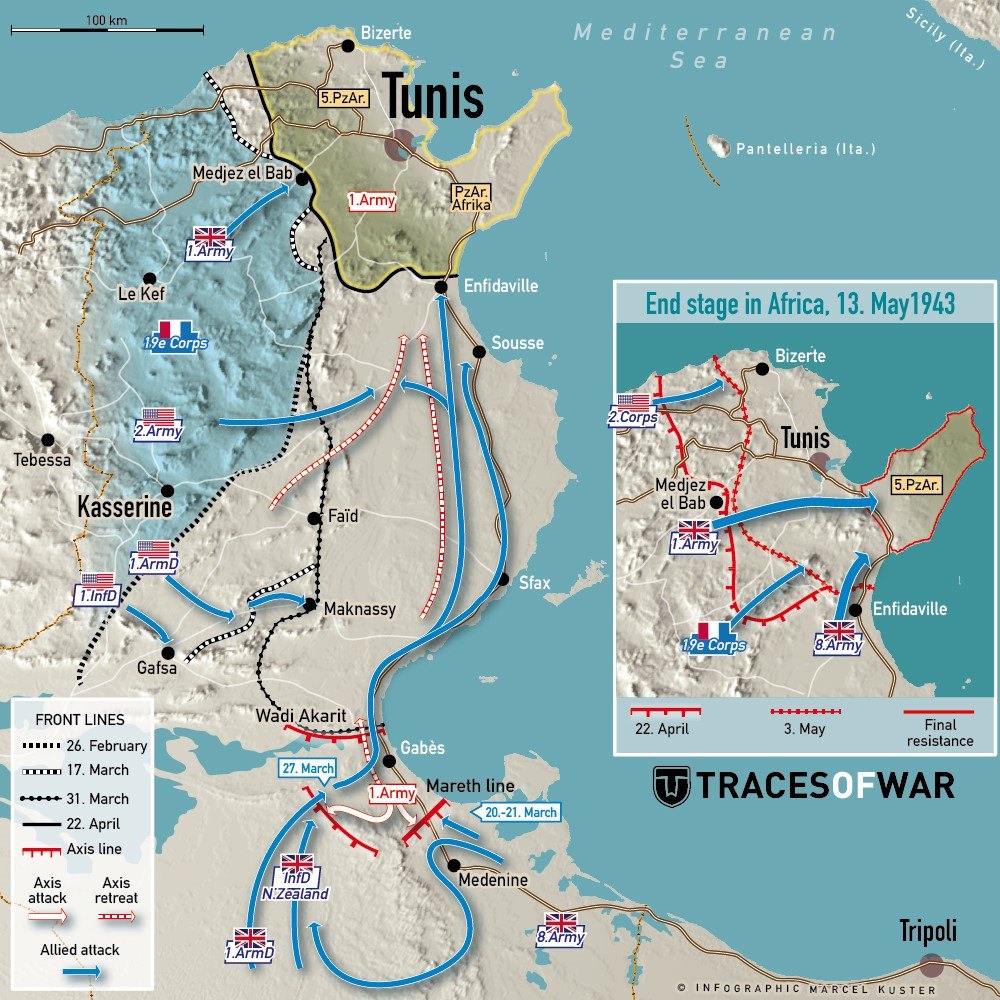

Panzerarmee Afrika retreated to Tunisia before that imminent attack and blew up Tripoli's port facilities on retreat. The troops retreated to the Mareth line, about 62 miles west of the Libyan border, where they were closer to the supply lines from Tunis and also closer to reinforcements that landed there because of Operation Torch. There was a short pause on the eastern front with the British (because the British had to restore the port of Tripoli), allowing Rommel to turn his attention to the western front, in collaboration with Generaloberst Hans-Jürgen von Arnim who was the new commander of the newly founded 5. Panzerarmee. He was not formally subordinate to Rommel, but to Kesselring as Oberbefehlshaber Süd, the German commander in the Mediterranean.

Definitielijst

- collaboration

- Cooperation of the people with the occupying forces, more generally spoken the term for individuals who cooperate with the occupying force is collaborator.

The last convulsions

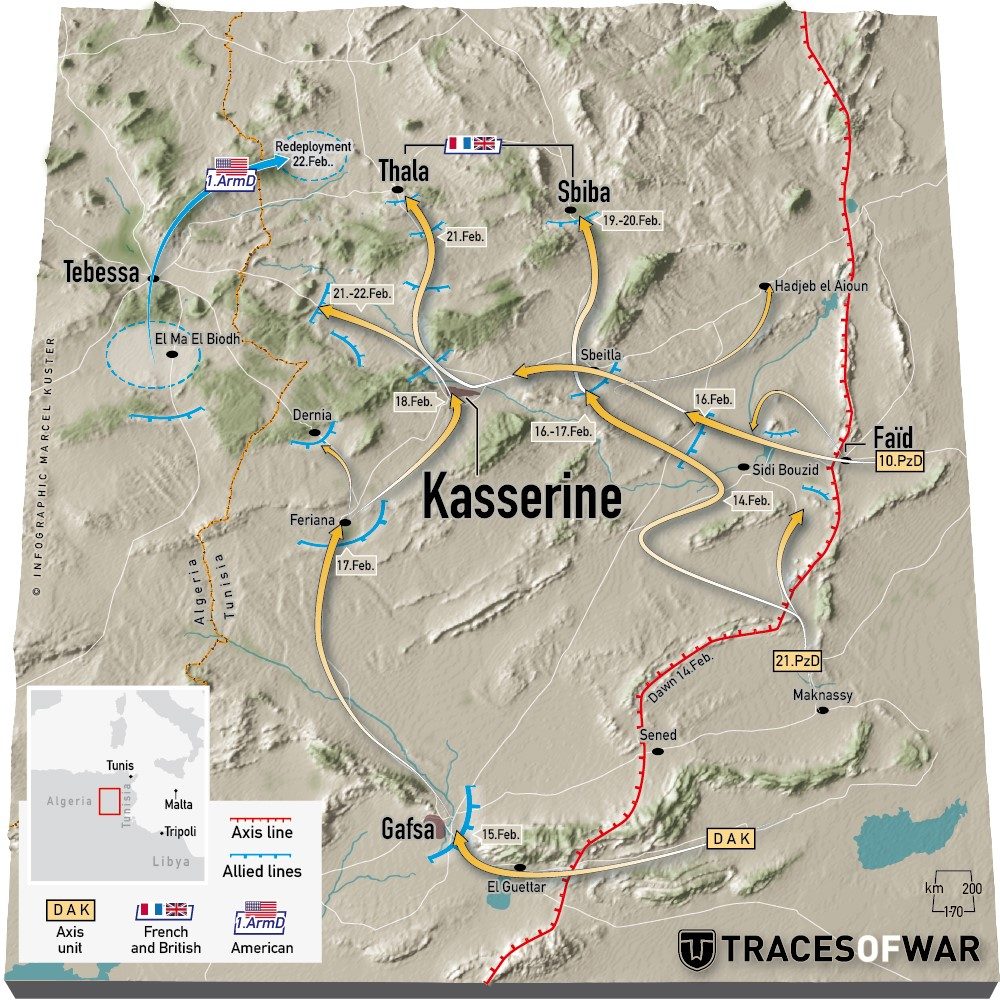

Von Arnim was put in charge of an attack in the west of Tunisia in February, with the aim of first driving the Americans and British back and possibly defeat them later. Rommel contributed with a so-called Kampfgruppe, a combat unit composed of the Afrikakorps, in this case with parts of the 21. Panzer-Division. This was complemented by parts of the 10. Panzer-Division of Von Arnim's army. Rommel managed to inflict a considerable defeat on the relatively inexperienced Americans and British on February 21, 1943, by conquering the Kasserine Pass and then forcing them into the defensive. Although this was a success, the American II. Corps, for example, lost more than 600 vehicles and 6000 troops, Rommel estimated the capabilities of the Americans and British in such a way that he didn't want to push on.. American reinforcements approached quickly and already on February 22, 1943, the losses started to accumulate as American-British resistance strengthened (reinforcements had been brought in). He also knew that the British in the east were still planning to launch an attack and that Panzerarmee Afrika had to face it as completely as possible.

Rommel’s last victorious battle in February 1943, the battle of the Kasserine Pass with his Kampfgruppe consisting of units of the Afrikakorps (DAK). Source: Marcel Kuster

The 21. Panzer-Division was not immediately released for the eastern front to help withstand an attack from the British. As a result, the Panzerarmee's eastern-based troops lacked essential troops to stop that attack. This also meant that there was no way to launch a successful counter-attack against the numerically superior British, who moreover, knew through intercepted messages exactly where the Germans' troops were located. A counterattack near Medenine was therefore quickly annihilated by the British. Rommel left the North-African battlefield on March 9, 1943, to be treated in Germany. He had been seriously ill for months and was also protected from captivity by Hitler. The command of Panzerarmee Afrika came into Italian hands and it was renamed the First Italian Army, although Rommel's Chief of Staff Fritz Bayerlein remained in charge of the German troops in that army.

From this moment on, March 1943, the German and Italian fought a lost battle. The Americans and British attacked the armies from the west and east, with a superior amount of men and weapons. The Panzerarmee gained fame by seemingly impossible victories but at the end of the day, defeat was inevitable. On April 22, Operation Vulcan was launched to close the ring around the German-Italian troops. Via Enfidaville and Medjez el Bab, the British and Americans entered Tunisia with superior forces. A successive operation, called Strike, ensured the capture of the capital Tunis and sealed the fate of the Axis troops in North-Africa. On May 13, 1943, all troops were taken prisoner and the North-African front was closed, resulting in a massive loss of 250,000 troops for the Germans and Italians. The battle was to continue on the European mainland. Because the Germans and Italians managed to keep Tunis, their dictators believed that a miracle was still possible. They sent fresh troops with brand-new equipment, despite warnings from their commanders to evacuate to southern Europe. All new troops, including equipment, were lost when the troops in North-Africa surrendered, leaving Southern Europe very vulnerable to an Allied attack.

Definitielijst

- Kampfgruppe

- Temporary military formation in the German army, composed of various units such as armoured division, infantry, artillery, anti-tank units and sometimes engineers, with a special assignment on the battlefield. These Kampfgruppen were usually named after the commander.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Reputation of the Afrikakorps and the Panzerarmee

Erwin Rommel was the charismatic commander of the Afrikakorps and then Panzerarmee Afrika. His presence alone made his men feel empowered in battle. Regardless of what status Hitler had attributed to Rommel, this was certainly Rommel's own merit. That certainly did not make him infallible, he also made mistakes, but it did give an enormous boost to the morale of his troops. The characteristic way of warfare, at high speed, concentrated and without long intervals, made the Afrikakorps and later the Panzerarmee famous. In addition, after the war, the image arose that the unit was more humane than other army groups of the Wehrmacht. That image needs nuance. In the article about the Einsatzgruppen on this website, you can read that Jews in North-Africa were also persecuted by an assassination commando led by SS'er Walter Rauff. There were also plans to deploy this Einsatzkommando in Palestine after the conquest of Egypt.

However, it can be assumed, that the German army in North-Africa treated its prisoners better than it did in the Soviet Union. While the struggle on the Eastern Front was portrayed in Nazi propaganda as a racial war against an enemy that was both racially and ideologically inferior, the British in North-Africa were considered an equal opponent. There are several examples of "chivalrous" actions by Rommel, although not all of them can be traced exactly. After the battle for Bir Hacheim, for example, Hitler ordered Rommel to execute all imprisoned members of the French Foreign Legion. However, Rommel ignored the order and had them treated like ordinary prisoners of war. There is also a story known of a British prisoner of war who complained to Rommel about the bad food they received, on which Rommel ordered them to give the same as his own soldiers. After the surrender of Tobruk, the 30,000 prisoners of war had little water for 48 hours, in part because of the chaotic situation. However, this also was the case for Rommel's troops. Some British officers demanded to sleep separately from the East Africans and Indians. Rommel rejected this demand, arguing that every soldier, regardless of origin, is the same and has the same rights.

When the troops of Rommel advanced towards El Alamein, the victories of Panzerarmee Afrika had severely broken the morale of the British. In Great Britain, the government of Winston Churchill was almost pushed aside (Churchill narrowly survived a vote of no confidence in parliament), and in Alexandria the British fleet was already preparing to leave. Demolishing squads were even called in to destroy the port installations. Many Egyptian citizens in Alexandria also lost confidence and left for Cairo en masse. At the British embassy in Egypt they already started burning secret documents. Finally, the commander of 8th Army, Auchinleck, was even considering giving up Egypt and retreating to Palestine. While these drastic activities did not reflect the reality on the battlefield at all — Panzerarmee Afrika — was vastly outnumbered in personnel, aircraft, vehicles and logistics), these activities do say a lot about the impact the Panzerarmee Afrika and commander Rommel had on all their victories.

It is interesting how people still talk about the Afrikakorps, when they want to designate the entire army in North-Africa, but this is factually incorrect, because in January 1942 the unit was given the status of an Armee and was therefore called Panzerarmee Afrika. In that capacity, it also existed longer and achieved the most striking victories, such as the capture of the port city of Tobruk. However, the strength of that Panzermee was formed by the Panzertruppen of the Afrikakorps with their tanks. They played an essential role in the way of warfare of Rommel's army.

Definitielijst

- El Alamein

- City in North Egypt. The Battle of El Alamein took place from October to November 1942 and was a turning point in the war. The German-Italian advance in North Africa was finally halted by the Allies.

- Foreign Legion

- French army unit whose soldiers and officers were foreign mercenaries. Also in Spain a foreign legion is part of the military forces.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Tobruk

- Small bunker. Usually manned by one soldier with a machinegun, but there were also bigger tobruks equipped with a canon or mortar.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Information

- Article by:

- Matthias Ouwejan

- Translated by:

- Fernando Lynch

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- HASTINGS, M., All hell let loose, Harperpress, London, 2011.

- KESSELRING, A., Soldat bis zum Letzten Tag, Verlag Siegfried Bublies, Schnellbach, 2000.

- LIDDELL HART, B.H., The history of the Second World War, Pan Macmillan, 1992.

- MITCHAM JR. SAMUEL W., Rommel’s desert war, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, 2007.

- PIMLOTT, J. e.a., Rommel and his art of war, Greenhill Books, London, 2003.

- REMY, M.P., Erwin Rommel, List Verlag, München, 2002.

- ROMMEL, E., The Rommel Papers.

- WESTPHAL, S., Generalstabschef dreier Feldmarschälle Rommel, Kesselring und von Rundstedt, Verlaghaus Würzburg, Würzburg, 2007.

Thanks to Fred Bolle, Wesley Dankers and Ed Woertman for their corrections and useful suggestions and to Marcel Kusters for having designed the maps.