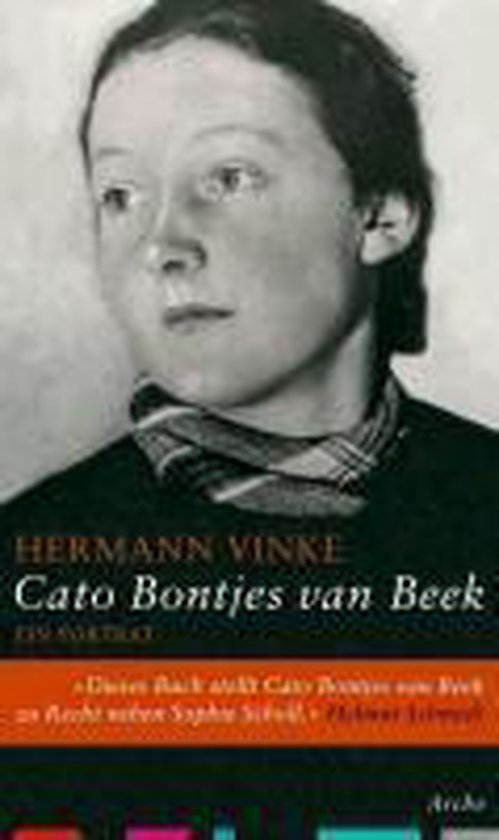

Cato Bontjes van Beek (1920-1943)

Introduction

"I only want to be one thing - a human being!" - Cato Bontjes van Beek

Cato Bontjes van Beek, known by friends and family as Dodo, was a happy-go-lucky child who lived life to the full. She made friends easily and was often found encouraging her brothers, sisters, and the neighbourhood children to go walking or swimming, or to take part in sports matches and theatre shows. Along with her gregarious nature, Cato was outspoken on matters of fairness and justice.

The Young Cato

Cato Bontjes van Beek was born in Bremen on 14 November 1920 to a family of painters, musicians and ceramic artists. She was the first daughter of the strikingly attractive dancer Olga Breling and the ceramist Jan Bontjes van Beek. Olga was the youngest of six daughters of painter Heinrich Breling and his wife Amelie, who were co-founders of the artist community in Fischerhude, a village close to Bremen. Jan was a German citizen, born of Dutch parents, maritime engineer Eduard and his wife Cato. In the First World War, Eduard volunteered as a sailor in the imperial Navy. His post-war revolutionary activities later earned him the nickname 'the red sailor'.

Two years after the birth of Cato came a sister, Mietje, and a year afterwards a brother, Tim. In order to take care of the household and bring up the children, their mother gave up her demanding dance career and became a painter and sculptor. As was normal in artistic families, the children were given free rein to develop themselves.

When Cato was eleven years old, she went to live with her aunt and uncle in Amsterdam. They had no children of their own. Cato attended the German Kaiser Wilhelm School there. For the eleven-year-old, living in a big, foreign city would have been an experience filled with new impressions and experiences. Cato's open and somewhat boisterous nature remained unchanged, much to the surprise of her uncle and aunt, who had expected a well-behaved girl, not a ‘tomboy’. The Nazis were not yet in power, and there was as yet no tension to speak of. The situation in Fischerhude had changed by the time Cato returned there. Just as in the rest of Germany, there were marches and torchlit parades, and banners and uniforms filled the streets. The Bontjes van Beek family paid little serious attention to these goings-on, and the children would laugh at their mother’s impressions of Adolf Hitler and Reichspropagandaminister Joseph Goebbels.

In contrast to a lot of other children, Cato, Mietje and Tim were not members of the Hitler Youth, and therefore could not participate in activities that were organised for members. However, at the insistence of their teacher, the Bontjes van Beek children received extra instruction on Saturday afternoons, in order to make them more 'respectful'.

Still, it seemed like a happy childhood. But dark clouds were soon to gather over the family. In 1933 Jan divorced Olga and left the house in Fischerhude for good. He went to Berlin to begin a new life with his new wife, Rachel Weisbach. Because of the children, Jan and Olga decided to keep in contact.

In January 1937, Cato, now 16, decided to go to England to work as an au pair and to learn the language better. Through her aunt Amelie Breling’s connections, Cato obtained a position with the Beesley family in Winchcombe, a picturesque village in the Cotswolds. The family and their visitor got along famously, the father even giving Cato driving lessons. To make some pocket money, Cato gave German lessons to English schoolchildren, spending the extra on theatre and film tickets. The experience that made the biggest impression was the fulfilment of her childhood dream: flying. A great admirer of Amelia Earhart, Cato flew in a double-decker plane, writing home enthusiastically about the experience. In her letters home the name ‘John’ came up more and more frequently. John Hall was a friend of the Beesley daughters, five years older than Cato and a student of agriculture. He was interested in Buddism, a subject that was also of great importance to Cato. She had begun to learn more about philosophy and religion, and in Hall she found a great conversationalist. Given all these new experiences and connections with mentors and friends, Cato understandably found it difficult when her time in England came to an end.

Definitielijst

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

A New Path

Once back in Germany, Cato had difficulty finding her life's purpose. She still had no idea of what she really wanted to do with her life, switching between aviator, theatre star, ceramist and globetrotter. In any case, she moved in with her Aunt Jossie and Uncle Hans Schultze-Ritter in Berlin who, at the request of Cato’s mother, were to further Cato's cultural education. This wasn't surprising, given Aunt Jossie's chosen profession of composer and Hans's occupation as a music teacher. Cato was, as in England, regularly found in theatres, museums and galleries. Her plan to become an aviator could not be realised immediately. At the insistence of her aunt and uncle, she was first to obtain a business education before deciding anything concrete. Cato agreed without a word of protest. She countered her disappointment by becoming a member of the 'NS-Frauensegelgruppe', an association of women gliders. That this organisation was national socialist did not bother her. Cato wasn't interested in politics, she wanted to fly! She wrote to her sister Mietje to say: 'I will always go my own way. No one can stop me. If I want to be an aviator, I'll be one.'

From October 1937 until April 1938 she followed a glider training course. But life took her in a different direction. After training as an administrator, she obtained an internship in Bremen at the engineering firm Heyse & Eschenburg. It wasn't the most suitable environment for her, but she decided that such experience was needed if she was later to work in her father's company. She had finally decided to follow her father's path and to become a ceramic artist.

In this period there was however some relief. A year after she left England, John Hall came to visit her in Fischerhude, much to Cato’s delight, and her mother and sisters were very impressed by the Englishman. An engagement between Cato and John was the logical outcome of the visit, after which John returned to England.

An Ominous Development

In the spring of 1939, Cato went through a phase wherein she dreamed of very unsettling events. These dreams seemed to presage future happenings, although Cato could not yet explain their meaning explicitly. The dreams first began about gliding. In these dreams Cato was caught with her glider in a heavy storm. In another dream, she was a guest of Kaiser Wilhelm II and his wife in Doorn, the Emperor’s residence in the Netherlands in which he lived after his exile from Germany in 1918. There, Cato had a political discussion with the Kaiser and his wife, in which she defended the opinion that all people should be paid equally, regardless of whether they were workers or scholars. The Empress did not agree. Later, Cato dreamed that she was sentenced to death, but did not know why. She witnessed her passage to the execution chamber and experienced her beheading.

In the autumn of 1939, Cato left Fischerhude to live with her father in Berlin. The Wehrmacht had occupied Poland, and the beginning of the Second World War was a fact. Cato felt powerless. Her sister Mietje joined her in Berlin. Cato worked in her father's company while attending graphic design classes. Jan was anti-Nazi and Cato became involved in smuggling food for Jews in hiding. She also helped collect money so that her father and his anti-fascist friends could buy food on the black market. Further, Cato assisted in the collection of clothes for young people who wished to escape Germany via the Alps.

Cato could not avoid the Reichsarbeitsdienst (RAD). Young women were obligated to spend half a year working in a business that was involved in the war effort or in agriculture. At the end of April 1940 she travelled to RAD-Lager Blaustein, in Kreis Rastenburg, East Prussia (now Kętrzyn, Poland), working first in a kitchen and then on the land. It was a hot summer and the work was heavy-going. Whilst at work, Cato suffered from an infection of the leg. As a consequence, she was able to return to Berlin in September. In her sickbed she read the Russian classics, awakening her political consciousness.

Back in Berlin, she quickly made new friends, including Katja Casella, an art student, and Hannes Lange, a student of medicine. Hannes was immediately attracted to Cato, but she did not return his love, for her heart was still with John Hall in England. Old friendships were also of great importance to Cato, such as that with Helmut Schmidt, who later became the Chancellor of West Germany. However, Schmidt broke off relations with Cato after reproaching her for taking too many risks. For example, during a party attended by Schmidt, Cato and her friends spoke negatively about the Nazis. The guests didn't know Schmidt at all: he could have quite easily been a Gestapo agent.

Daily, whilst commuting between her father's business and their house, Cato witnessed the departure of French prisoners who were sent on the S-Bahn [Stadtschnellbahn, intercity train] to forced labour camps. Outraged over their fate, she decided together with her sister Mietje and three friends to supply food to the men. Just before their departure, the women mingled with the passengers and handed out food, cigarettes and sewing materials. According to the law of the Third Reich, such actions made the women guilty of high treason, but this fact seemed of little importance to them.

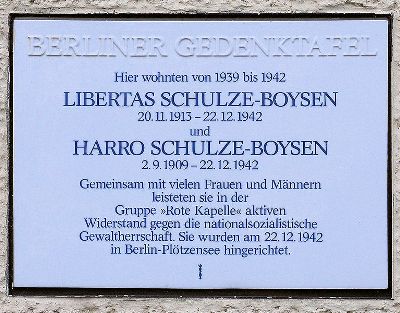

In the beginning of October 1940, Cato became a member of the Rittmeistergruppe, a collective of communist and anti-fascist idealists set up by neurologist and psychotherapy professor John Rittmeister.[1] Her motivation came from the raids that sought to remove all Jews from Berlin. Her Jewish neighbours had fallen victim to the relentless persecution, and Cato knew exactly what awaited the Jews. She had heard about the extermination camps from soldiers on leave, and was determined to resist the regime. But that was not the only thing that pushed Cato to action. She found the constant marches, swastikas, and mass rallies alarming, and felt compelled to act. 'Old people talk, young people take action', she said, and she intended to stick to her words. The aim of the Rittmeistergruppe was to instil peace through discussions and lectures. Young people gathered once a week in Rittmeister's apartment to discuss the political matters that occupied them. This passive approach came to an end in June 1941, when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. The group worked together with the Schulze-Boysen collective[2], which was set up and led by Harro Schulze-Boysen, lawyer and officer of the 'Luftfahrtministerium' [the Aviation Ministry], and his friend Arvid Harnack, economist and legal secretary. They had links with the Soviet government, although this fact was not known by the young members. Rittmeister was given the task of collecting information via foreign radio stations. Any important information that was collected was to be given by Rittmeister to Schulze-Boysen. The latter then used the intelligence in pamphlets and a paper called Die Innere Front.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Reichsarbeitsdienst (RAD)

- Labour service for men between the age of 18 to 25 years old introduced in Nazi Germany in June 1935.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

An Important Meeting

After Cato indicated that she wished to be more involved in the resistance, Jan Bontjes van Beek wanted to help his daughter. He knew Libertas Schulze-Boysen, Harro's wife, personally and introduced Cato to her.[3] Libertas was at that time working at the Ministry of Propaganda. An attractive blonde woman, Libertas was a model of sophistication. Cato was immediately impressed. The two women became friends and Libertas introduced Cato to the circle of friends around her and Harro. Libertas collected photos from the front via the 'NS-Kulturfilm-Zentrale', and Cato was for the first time confronted with the atrocities of the Einsatzgruppen [SS units]. Libertas noticed that Cato was ready to become more active and, to Cato's great enthusiasm, she invited her to join the resistance group. Cato helped with the paper and with the development of a six-sided pamphlet – Die Sorge um Deutschlands Zukunft geht durch das Volk – in which the group called for the overthrow of the regime.

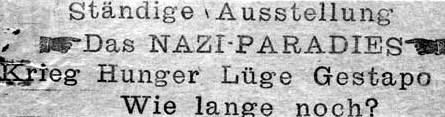

The pamphlet was distributed to a wide audience, and fell into the hands of the Gestapo. The finding of the treatise would eventually entail many arrests and executions, but in the early spring of 1942 no one suspected this outcome, least of all Cato. She was once again in love. Having lost hope of a future with John Hall after she had long waited in vain for communication from him, she had met a new boyfriend in the beginning of October 1941. Heinz Strelow was a former journalist for a communist newspaper, and came from a communist family that had contact with the Breling and Bontjes van Beek families in Fischerhude. Just after Hitler had come into power, Strelow was arrested for resistance activities and was a prisoner in a concentration camp. When war broke out he was exempted from frontline service because his mother, as a WWI widow, was dependent on her only son. Eventually, he was assigned as a non-commissioned officer to a weapons depot in Berlin, where he met Cato. A close friendship developed between them. After an argument with her father, who disagreed with his daughter’s plan to visit Fischerhude, Cato left the house and took on an old apartment with Heinz. Through Cato, Heinz also became a member of the 'Rittmeistergruppe'. Cato and Heinz wrote and copied pamphlets for the group, signing with the name Agis, after a king of Sparta who wanted to bring democracy to his people. The group members hoped through the distribution of the pamphlets to inform all Germans about what was happening under Nazi rule. But the group was also beset by internal problems. Heinz disapproved of Harro Schulze-Boysen's actions, which he saw as reckless in the extreme. Harro decided the mood and the momentum of various different campaign initiatives and let his opposition to the regime be known in a very public and expressive manner. For example, when the Nazis opened 'Das Sowjetparadies', an anti-Soviet exhibition, Harro had flyers with words such as 'Lies, Hunger and War' distributed around the city, despite resistance from other members. Cato's sister Mietje, who was also active in the resistance, found Harro a cold and callous man and was not interested in joining the faction. Soon, Heinz and Cato decided to leave, a decision that was made stronger by their dislike of Harro Schulze-Boysen’s aggressive leadership style. For example, when Cato refused to write a pamphlet calling for the sabotage of war material destined for the Russian front, he demanded that she complete the assignment, despite the fact that Cato had a brother, a nephew and friends fighting on the Eastern Front, and the exercise could put them in danger. Their withdrawal was however too late to prevent outside attention. The Gestapo already had both Cato and Heinz in sight.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- democracy

- From the Greek: demos (the people) kratein (rules). Democracy is a form of government elected by the majority of the people in which the people can check on the leaders and have the government resign in case a majority of the people no longer agrees with the government.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

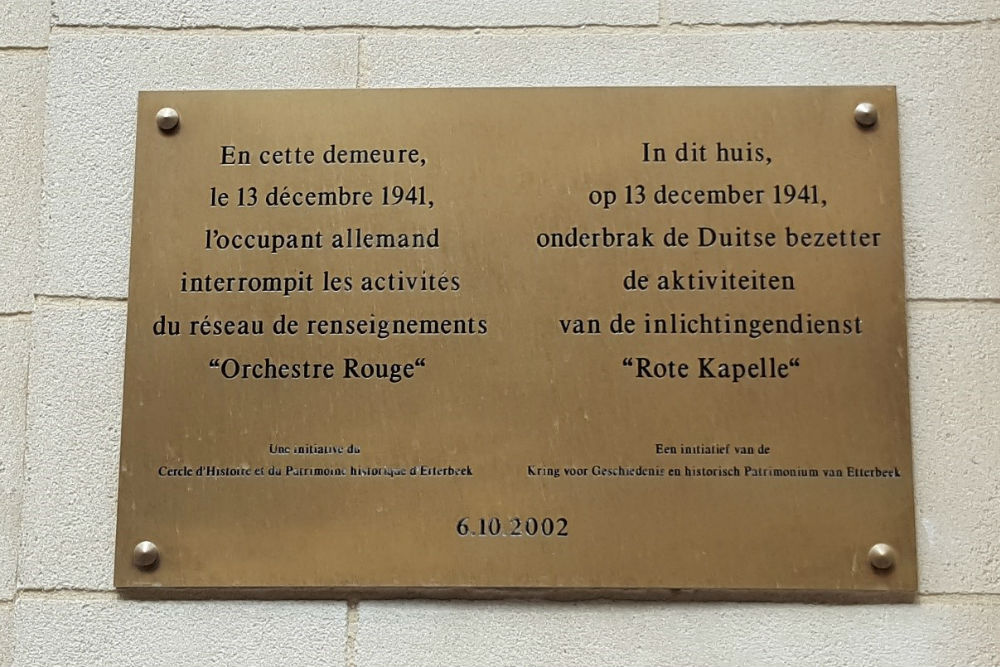

The Arrests

In the summer of 1942, Cato Bontjes van Beek walked for three weeks through the 'Böhmerwald' (the Bohemian forest) and the 'Bayerischer Wald' (the Bavarian forest), unaware of her impending arrest. On 30 June, the Gestapo dealt the final blow to the ‘Rote Kapelle’ or ‘Red Orchestra’ organisation, which was in fact a collection of resistance organisations that included the Schulze-Boysen collective. The radio liaison officer Johann Wenzel was arrested and the code was obtained by the Gestapo. The Russian secret service was unaware of the developments, and the Gestapo were able to gather the essential information needed to shut down the German side of the network. The Schulze-Boysen couple were arrested, and from that moment on other arrests quickly followed, partly due to informants who were placed in the cells with the prisoners. Heinz Strelow and the married couple, Arvid and Mildred Harnack, were also arrested.

Three months later, in the early morning of 20 September 1942, Jan and his daughter Cato were arrested at Kaiserdamm 22 in Berlin. They were taken away separately. Jan was taken to the Gestapo headquarters on Prinz Albrechtstrasse 8 and Cato was brought to the police station on Alexanderplatz. Her sister Mietje managed to avoid punishment. Jan was also lucky, being set free after three months in Spandau prison. No one, not even Cato herself, thought that she would be sentenced to more than a few years' prison. Nevertheless, her family worked to secure her release. Her mother Olga was at this time often in Berlin, as she wanted to be as close as possible to her daughter. She visited Cato frequently, bringing her food and clean laundry.

Definitielijst

- Gestapo

- “Geheime Staatspolizei”. Secret state police, the secret police in the Third Reich.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

The Trials

In December 1942, the trials of those arrested began at the 'Reichskriegsgericht' (the highest military court in Germany) in Berlin. The first trials were of the Schulze-Boysen couple, the Harnacks, Hans Coppi and seven other members. The chief prosecutor, 'Generalrichter' Manfred Roeder, was one of the most zealous. In the capacity of 'Oberkriegsgerichtsrat', Roeder was responsible for the sentencing of members of the 'Rote Kapelle' that marked the end of that organisation. He was subsequently responsible for the implementation of at least forty-five death sentences. During the trials, Roeder learned a great deal about the objectives of the 'Rote Kapelle'. He was convinced that the resistance organisation was in fact an espionage operation in the service of the Soviet Union. The death penalty was, given this conviction, a certainty for all members, including Mildred Harnack and Erika von Brockdorff, who were first sentenced to prison, until, one month later in January 1943, they were sentenced to death.

Generalrichter Manfred Roeder as a witness during the trial of Nazi jurists in 1947. Source: United States Army Office of the Chief of Counsel for War Crimes

Cato had learned about the death sentences of Arvid Harnack and Harro and Libertas Schulze-Boyson that were carried out on 22 December. However, she still hoped that her fate would be different. In prison, she got on with everyone, even the guards. She recited poetry, whistled, sang and exercised without being bothered by anyone. She also repaired male prisoners' socks and sent encouraging letters to their young family members.

On 15 January 1943, the 'Reichskriegsgericht' passed more judgements. Among the nine accused were Heinz Strelow and Cato Bontjes van Beek. In the so-called reasoning presented to the court - the sentences themselves were fixed long before - Roeder spoke strongly against the 'immoral' and 'decadent' lifestyle of Cato and Heinz. In particular, Heinz was still married; his wife was living in Hamburg. In further reasoning for the judgement, it was stated that Cato and Heinz's apartment was used for conspiratorial meetings. According to Roeder, discussions about leaflets and other subjects took place there. The actions that Cato carried out with Mietje at S-Bahn stations for the benefit of French prisoners remained unknown to the Gestapo, and these acts were therefore not taken into account in the trials.

On 18 January, the seven accused were sentenced to death, including Cato, due to 'participation in the preparations for high treason and assisting the enemy'. Cato expected that the sentence would be carried out quickly, as was the case with the first trials, and this idea put her completely at ease. She wrote to her mother to say: 'I feel a love for you, and for all other people, in myself. I am free of any feeling of revenge or hate’. Cato wrote letters unceasingly, until the very last moment.

Whilst waiting for the sentence to be carried out, Cato's family, friends and acquaintances wrote to the authorities to plead for mercy. The 'NS-Frauensegelgruppe' also submitted an appeal. The most important goal was to win time so that Cato’s supporters could fight for a review of the sentence. Cato herself wrote in support of her boyfriend Heinz Strelow. 'A person that writes such poetry could never pursue materialism, and therefore also cannot be a communist’, she argued[4]. In the same letter, Cato added that she expected no mercy for herself, if Strelow was not saved from the death sentence. Her attempt was in vain. On 13 May 1943, Heinz Strelow was executed by guillotine.

After mass death sentences were announced for a second time, many state prosecutors had had enough of Roeder's obsession. They turned against Roeder and argued for the acquittal of Liane Berkowitz and Cato Bontjes van Beek. 'Reichsmarschall' Hermann Göring, who had authority for such cases under Adolf Hitler, recommended that the death sentence of Cato Bontjes van Beek be revised. Hitler was however in favour of harsh sentences for resistance fighters and rejected all recommendations of mercy. The death sentence was upheld.

Tim Bontjes van Beek, Cato's brother, knew nothing about the resistance activities of his sister. Called up for military service, he had been fighting with the Wehrmacht on the Eastern Front since the summer of 1942. His dream of becoming a pianist was put on hold. In every letter that he wrote, he asked, 'How is my poor Dodo?'. He also wrote directly to Hitler's office to plead for clemency. To Tim's surprise, he was granted leave in order to visit his sister. Cato heard this information not long before they were reunited. He described the meeting thus: 'She wept bitterly when she saw me. I could hardly recognise her, she had lost so much weight from the watery soup. I fought back tears, and could barely speak.' After that day, 18 June 1943, Tim never saw his older sister again.

In the beginning of May, Cato was brought to the women's prison on the Barnimstrasse in Berlin. The news hit the family hard. It was not a good sign, and the fear increased that the sentence would indeed be carried out. On 24 July, Mietje was permitted to visit Cato. She described the visit to their mother: '[...] Cato was led in, in clogs, socks and a grey blouse. The guards stayed close by and I could hardly breathe’. 'How long can you hold on?' I asked. Cato replied: 'Until here!' and pointed to the letters on her armband - TK - 'Todeskandidat' - death sentence.

Definitielijst

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

The End

Thursday 5 August 1943 was a beautiful summer's day, the kind which Cato loved so much. She was taken, together with twelve other women and girls, to the Plötzensee prison. The realisation was sudden: it was over. Death would not be long in coming now. She still wanted to write letters to her brother Tim, sister Mietje and her mother Olga. At 16:45, she asked Pastor Ohm to celebrate the last meal with her. The church had never been a comfort to her, but the Bible, and especially the New Testament, was of great importance to Cato. At 19:00, she was taken to the section of the prison where the sentence would be carried out. She had just 40 minutes to live before the guillotine would end her young life. Fearless and unperturbed, the twenty-two-year-old Cato faced a death just like the one she had envisaged in her dreams two years before. From descriptions of the prison operations, we know that executions took place every three minutes. Cato would be the second-to-last prisoner executed that day. The time of the execution was 19:42. On the same day as Cato, fifteen others were also killed: twelve women and three men[5]. Hilde Coppi was one of the women. Her son Hans was eight months old when his mother's life was taken by the guillotine. Liane Berkowitz was the mother of a girl just a few days old. For her also, no mercy was shown.

Hilde Coppi was executed in 1943, after nursing her child for a period of a few months. Source: U.S. National Archives

Liane Berkowitz was pregnant, but this fact only delayed her execution until the baby was born. Source: U.S. National Archives

Still No Rest

The bodies of Cato Bontjes van Beek, Libertas Schulze-Boysen and Liane Berkowitz were not buried. They were instead brought to the Anatomical Institute of Charity in Berlin for autopsy. Corpses were often made available to hospitals for research purposes. The principal physician that carried out such practices was the gynaecologist and anatomist Hermann Philipp Rudolf Stieve (1886-1952), head of the Anatomical Institute.

Corpses were used for research, education, and medical illustrations. Before the Third Reich, anatomists obtained bodies from hospitals, psychiatric institutions and, to a lesser degree, from prisons. With the arrival of the Nazis, the number of executions in prisons increased sharply, often for minor offences. Nazi pathologist anatomists became an integral part of the machinery of death, and every prison that had an execution room was assigned an anatomical institute, and the anatomists were notified when executions were to take place. Stieve carried out research mostly on menstruation in young women. He had an obsessive interest about the influence of stress and terror on the female reproductive system. As soon as the date of an execution was known, Stieve would begin to observe the woman in question in order to determine the effects of the news on the prisoner. Soon after the execution, the body was made available to Stieve. It is known that he carried out autopsies on around 172 women. Amongst them were thirteen female members of the Rote Kapelle, that were beheaded by the Gestapo, but the corpses of some male members of the organisation also ended up in the hands of Stieve, including those of Harro Schulze-Boysen and Arvid Harnack.

Definitielijst

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

Epilogue

Cato Bontjes van Beek was not a political resistance fighter, was not religious, and not an intellectual. Yet she was daring, in an almost child-like way. Was she too naive? The police photos show a relaxed, almost smiling young woman in the bloom of her life. She loved life, and death was the last thing that she wanted. Her strong sense of justice and her compassionate nature gave her strength to resist the Nazi regime despite the risks. On her own account, her dreams had already warned her of what was coming and, together with her faith, they contributed to her calm reconciliation with death during her detention and trial.

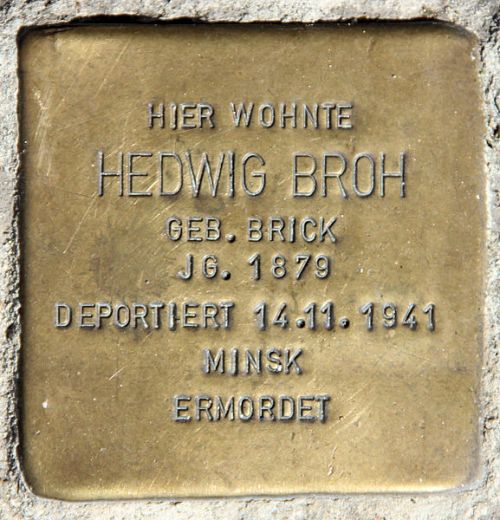

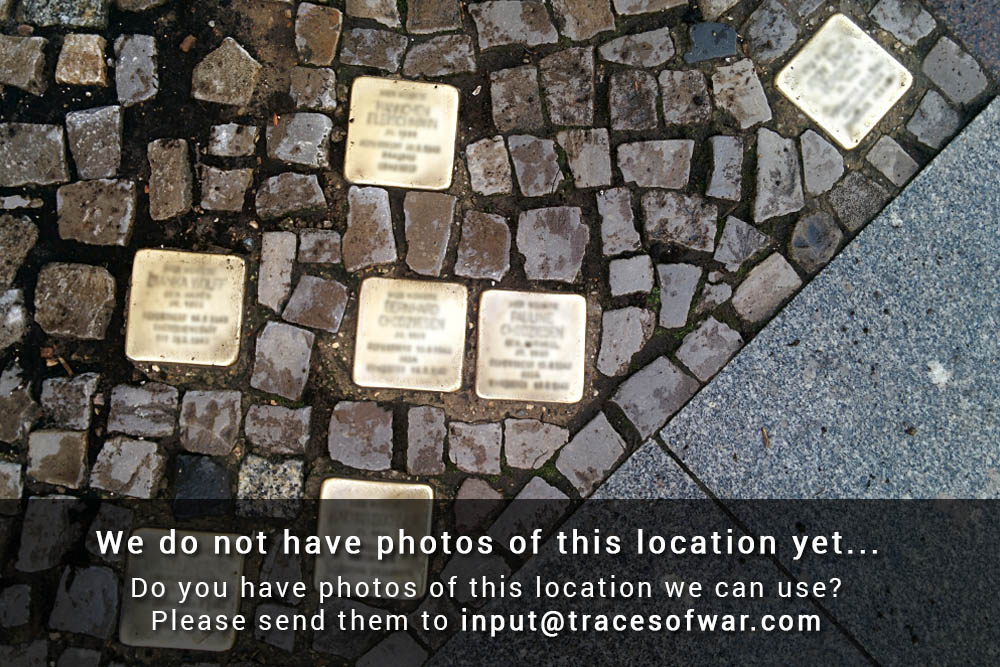

A memorial plaque (Stolperstein) in front of the house at Kaiserdamm 22 in Berlin-Charlottenburg. Source: OTFW, Berlin

After The War

The legend that the 'Rote Kapelle' was a spy ring persisted in the West decades after the war, not least because of Roeder. He found that the British and American intelligence services were interested in his findings. Decades later, Olga Bontjes van Beek continued legal proceedings for twelve years against the state of Lower Saxony to obtain her daughter's pardon, which was finally granted in 1999. ‘It's a shame that I will leave nothing behind but the memory of me,’ Cato wrote in her last letter to her mother. In the former German Democratic Republic, members of the 'Rote Kapelle' were considered heroes long after the war.

After the Fall of the Wall

In 1991 the gymnasium in Achim near Bremen changed its name to the Cato Bontjes van Beek Gymnasium. On the 14 November 2010, the Cato Bontjes van Beek Archive was opened by her brother Tim.

Notes

- Professor John Rittmeister (1989-1943) described himself as a humanist. On the 26 September, Rittmeister was arrested with his wife Eva. John was sentenced to death and he was executed in Plötzensee on 13 May 1943. Eva Rittmeister was sentenced to three years' prison, and was freed in April 1945.

- The Schulze-Boysen group was part of a more extensive organisation that would become known as the Rote Kapelle.

- Libertas Schulze-Boysen was born in Paris November 20, 1913 and executed on December 22, 1942 in Plötzensee.

- 'Materialism' here is meant in the philosophical sense. Materialists believed that everything in life and the universe can be traced back to matter. Materialism had many adherents, especially in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

- From 19:00 on 5 August 1943, the following men and women died under the guillotine at intervals of three minutes: Stanislaus Wesolek, Emil Hübner, Dr. Adam Kuckhoff, Frida Wesolek, Ursula Goetze, Maria Terwiel, Oda Schottmüller, Rose Schlösinger, Hilde Coppi, Klara Schabbel, Else Imme, Eva-Maria Buch, Anni Krauss, Ingeborg Kummerow, Cato Bontjes van Beek, and Liane Berkowitz

Definitielijst

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Information

- Article by:

- Annabel Junge

- Translated by:

- Tomas Brogan

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!