Introduction

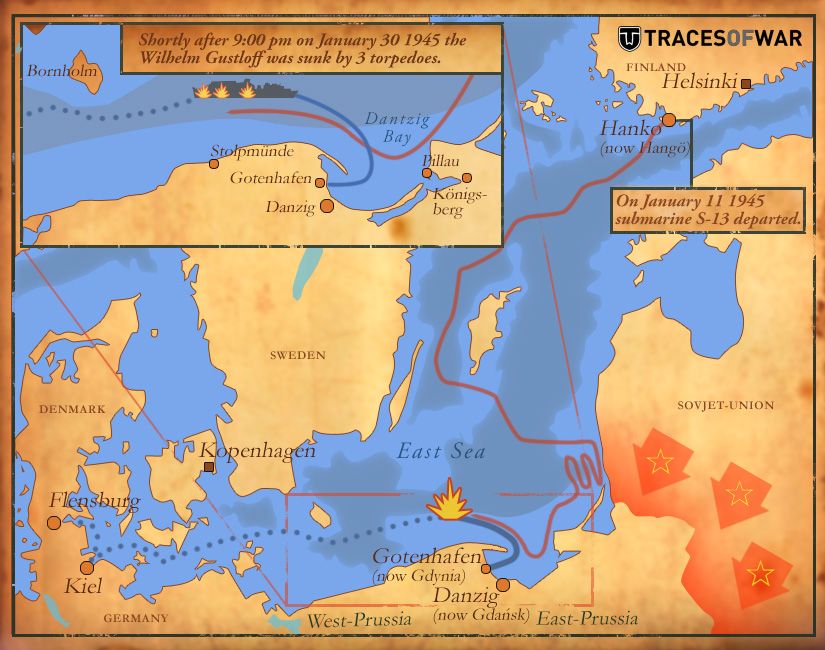

On January 30, 1945, at 21:45 hrs. The Nazi vessel Wilhelm Gustloff was hit by a torpedo. Moments later, a second and third torpedo hit the German ship with over 10,000 people aboard of whom almost 9,000 were civilian refugees. Seventy minutes later the former Nazi cruise ship was sunk and over 9,000 persons aboard were dead. The sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff is recorded in history as the greatest maritime disaster of all times. The three torpedoes were fired by the Soviet submarine S-13, under the command of Kapitan III ranga Alexander I. Marinesko. During the same mission, the S-13 sank another large German evacuation ship. On February 10, 1945, the Steuben was sunk by two torpedo hits. Nearly 4,000 persons aboard were killed in this disaster, again, most of them German refugees.

For the Germans, these maritime disasters were doubly bad luck, because, strictly speaking, the S-13 was not allowed to sail. On January 2, 1945, the S-13 should have left port because of the new Soviet offensive to expel the Germans from the Baltic. The S-13 and her crew were ready to leave, but their commander, Marinesko was not. He had been on shore leave for three days in the Finnish Turku but had failed to return to his boat, which was based in the occupied Finnish port. While the Military Police were looking for him, he returned on January 3, reporting that he could remember little of his escapades in the Turku nightlife. The secret police suspected him of desertion and treason, but he was lucky that his immediate superior believed him when he claimed that he had merely gone on a spree. His commanding officer needed Marinesko in order to allow the S-13, one of the better submarines of the Fleet, to leave port. Thus, eager to make up for his transgressions, Alexander Marinesko left towards the demise of the Wilhelm Gustloff and the Steuben.

After sinking these two German vessels. Marinesko was the tonnage ace of the Soviet submarine Fleet. Both German vessels represented a tonnage of over 42,000 tons together and no other Soviet submarine had come close to reaching that number. Marinesko expected to receive nothing less than the prestigious title of Hero of the Soviet Union. However, the Soviet authorities did not consider this title appropriate for him. When the sinking of both the German ships was acknowledged Marinesko was given the Order of the Red Banner. After the war, he was even relieved of his command due to problems with discipline, alcoholism and misconduct. He was demoted to Starshyi Leitenant (Lieutenant, 2nd Class). In October 1945 he was discharged from the Soviet Navy and tried to find a job in the merchant navy. In January 1946 he had to settle for a job as a warehouse manager in Leningrad. In this position, Marinesko was falsely accused of theft, convicted and sentenced to a Siberian camp. He survived the camp terrors, but died of cancer in 1963. In 1990 he was posthumously honoured with the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

Definitielijst

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Youth and education

Alexander Ivanovich Marinesko was born on January 15, 1913, in Odessa on the Ukrainian Black Sea coast. His mother was Ukrainian and his father, a Romanian sailor had fled to Odessa after being involved in one of the many mutinies during the Balkan wars and had changed his name from Marinescu to Marinesko. His son Alexander grew up in a city that became part of the Soviet Union, due to the fact that in 1922 Ukraine itself was proclaimed an independent Socialist Republic. In 1928, at the age of 15, he left the school where he had learned little more than to read and write. He got a job as a cabin boy on a cargo ship, but an authority with a lot of insight for talent noticed him and within a year, in 1930, Alexander Marinesko was enrolled at the maritime school in Odessa and in 1933 he completed his education. After concluding his training, he quickly rose to the rank of mate on a coaster of the Black Sea. The great breakthrough in his career came when he managed to save the crew of a torpedo-boat that capsized in a storm near the coast of the Ukrainian port of Skadowsk. The story of Marinesko’s courageous behaviour spread throughout the Black Sea Fleet and the Soviet navy persuaded him to join the navy and to receive training as a navigator, which he completed in November 1933. One year later the Odessa sailor opted definitively for the submarine service.

Alexander Marinesko turned out to be a born submariner. His street-boy past in Odessa had made him resourceful, and he turned out able to cope calmly with all possible circumstances. Moreover, he soon discovered his ability for leadership. He realized that he would never stand out in the navy if he did not choose smaller ships, where he could exercise his individualism. At the right moment, he chose the submarine service, as many crews were needed for the many new submarines that were planned in the various navy yards. The officer training for submarine crews was intensive, strict and heavy, but Marinesko passed with flying colours, and in March 1936 the sailor from Odessa was promoted to leitenant (sub-lieutenant). Shortly after that he became a member of the Komsomol, the organisation for young communists and a fanatic supporter of Stalin. The only thing against him was his passion for vodka and girls, dating from his youth.

After completing his nine month training period, Marinesko was appointed navigator on the submarine Sjtsja 306, launched a year earlier. Six months later he was sent back to school for training to become a submarine commander. This training he completed with great success, and in the summer of 1937, at the age of 24, he was appointed commander of the submarine M 96 at the rank of starshyi leitenant. The submarine had recently entered service and was a slightly improved Type XII version of the previous Malyutka-class (M-class) boats. The M-96 was only 45 metres long and had a displacement of no more than 250 tons and an armament of a mere two torpedo tubes and a 45 mm deck gun. Commander Marinesko and his 18 man crew, however, got along very well with this basic submarine that was stationed in Leningrad. In a time when the Soviet Navy was torn apart by Stalin’s purges, the M-96 set one record after another. Marinesko’s submarine was able to dive in 19.5 seconds against an average of 28 for the other boats in the Baltic Fleet and his training torpedoes nearly always made a hit. During the years preceding the Second World War, it was the best lead submarine with the best-trained crew of the Baltic Fleet.

Definitielijst

- Odessa

- Organisation of Former SS-members. Secret organization of and for former SS-members. Organised new identities and housing abroad after the war.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Second World War

The first years of the Second World War were very disappointing for Alexander Marinesko and the other submarine commanders of the Baltic Fleet. During the winter of 1939/1940, the Red Army fought the Winter War against Finland. With a relatively small army, the Finns succeeded in withstanding for months the overwhelmingly superior Soviet force, but the Baltic Fleet did not take part in this land struggle. After the courageous Finns were forced to their knees, the Soviets demanded large areas at the Finnish-Russian border, as well as the Finnish port Hanko on the eponymous peninsula. The Finnish port would be leased by the Soviets for thirty years. On June 22, 1941, the Germans invaded the Soviet Union as part of Operation Barbarossa. The embittered Finns had joined the Germans and recaptured at a rapid pace the lost territories. Soon, on September 8 of the same year, the Germans started the siege of Leningrad, which lasted until the beginning of 1944. The greatest feat of the Baltic Fleet, in difficult times for the Soviet Union, was the successful evacuation of Soviet troops from Tallinn, Estonia, in August 1941. The same Baltic Fleet got trapped by German and Finnish minefields and Hanko, Tallinn and other Baltic ports could no longer be used as bases. Moreover, the home base Leningrad was more and more difficult to reach. Kronstadt, a port on an island in the Gulf of Finland, 30 kilometres west of Leningrad, was forced to become the main base of the Baltic Fleet and consequently also for Alexander Marinesko.

Alexander Marinesko, the zealous submarine commander was annoyed by the fact that he was forced to observe the progress of the war in idleness, while the Germans and their allies penetrated further and further into the Soviet Union. However, it was going to get worse. On February 12, 1942, the M-96 was hit by a German artillery shell near Kronstadt and the submarine had to go into repairs for four months. Marinesko was forced to watch his crew lose their skills and training and he sought solace in drink and women. His alcohol abuse in particular, caused him problems, and he was excluded as a candidate for membership in the Communist Party. In the summer of 1942, Marinesko got a chance to show what he and his crew were worth. During a war patrol off the Finnish coast on August 14, he spotted the German gun platform Schwerer Artillerie-Träger SAT-4 Helena. The M-96 fired a torpedo on the enemy ship and Marinesko noted in his logbook that he had sunk a 7.000-ton enemy warship. After the war, the German vessel was salvaged, and it turned out to be only 400 tons. Marinesko had more than once exaggerated his reports, which made him untrustworthy with some of his superiors.

In October 1942 the M-96 was given another chance to prove itself. Alexander Marinesko and his crew were ordered to drop a commando team on the coast of the Gulf of Narva, Northern Estonia. The commando team was instructed to capture a German Enigma decoding machine. The attack on the German headquarters in Estonia failed and only half of the commando’s returned aboard the M-96, without the decoding machine. However, commander Marinesko fulfilled his task correctly and was awarded the Order of Lenin and promoted Kapitan III ranga (lieutenant commander). The most important factor for Marinesko was that he was allowed to be a candidate for the Communist Party again.

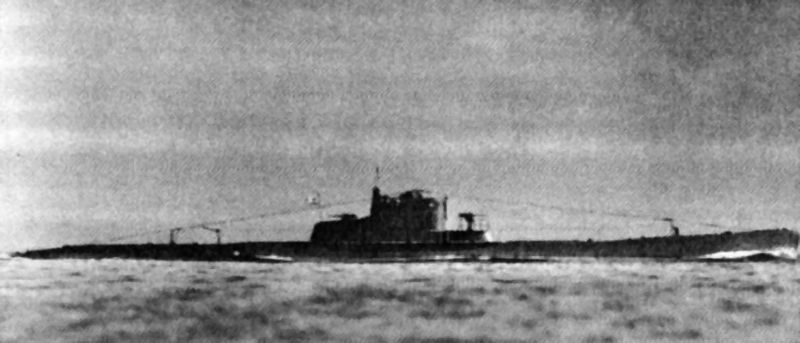

At the beginning of 1944, Marinesko was given the command of the modern Stalinets-class submarine S-13. This submarine, with a length of 78 meters and an underwater displacement of 1.050 tons was commissioned on July 31, 1941, and had already sunk, under the command of Kapitan III ranga Pavel Malantyenko, three enemy merchant vessels. The transfer to the S-13 coincided with the end of the German siege of Leningrad, on January 27, 1944. On September 5 of the same year, Finland made peace with the Soviet Union, which meant that the Gulf of Finland and its ports became available again for the Baltic Fleet. All this together offered Marinesko a much brighter prospect than the previous period. In October 1944, S-13 left her base in Hanko and a few days later took up position for the Bight of Gdansk, north of German-occupied Poland where much German shipping took place. On October 9, the S-13 spotted the German armed trawler, Siegfried, used as communications- and transport vessel. Marinesko fired all four bow torpedoes at the German vessel but all four underwater projectiles missed their target. Marinesko surfaced the S-13 and fired with the 100 mm deck gun on the Siegfried till she started to list. Later on, Marinesko claimed in his logbook that he sank a German ship of 6,000 tons. In reality, however, with the help of a tugboat, the 563-ton Siegfried was able to reach the port of Gdansk.

On December 31, 1944, the S-13 was moored at Smolny, the Finnish port of Turku. Stalin had ordered the submarines of the Baltic Fleet to launch a major offensive against German shipping in the Baltic Sea. On January 2, 1945, the S-13 would sail to obey this order. The submarine had taken on oil, torpedoes and supplies, and the crew was ready, but commander Marinesko was not. He had gone into hiding in the pubs and brothels of Turku and finally returned to his submarine on January 3. The military police had been searching him for a day. Marinesko’s superior, Kapitan 1 ranga (captain) Jevstafjevits Orjel, was convinced that the absence of his favourite submarine commander was due to an old fashioned Russian orgy of brawling and feasting and wanted to dismiss him with a reprimand. Orjel was well aware that, if he had taken Marinesko into custody, the S-13 would not have been able to set sail for an extended period and consequently would have been unable to obey Stalin’s order. The Narodnjj Komissariat Vnoetrennich Djel (NKVD), the secret service, however, had a different opinion on the matter.

The NKVD subjected Marinesko to a rigorous investigation and concluded that the controversial submarine commander should be transferred to Kronstadt on suspicion of desertion and treason due to extended and unauthorized absence in a foreign port. The crew of the S-13, led by Marinesko’s friend and first officer Kapitan III ranga Lev Jefremenkov, offered a petition to Orjel, stating that the S-13’s crew wanted to set sail as soon as possible to chase the fascists out of the Baltic Sea and that their commander should be allowed to resume his duty on board. Orjel considered Stalin’s total submarine war more important than the conviction of a prime submarine commander by the NKVD. However, by that time, the Soviet Union’s secret state police had already opened a file on Alexander I. Marinesko.

Definitielijst

- Enigma

- Cryptographic (de)coding machine used by the Germans during World War 2. The code was broken by the British with help from the Poles. Much German military information was known to the British in advance. This was a huge aid to the war effort.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Successes and disappointments

The S-13 had been given a fixed patrol sector at the Bight of Gdansk when she left the port of Hanko on January 11. More than 10 days later a message was received from the headquarters of the Baltic Fleet directed to all its submarines: "Offensive Red Army direction Dantzig developing well and will presumably force the enemy to the evacuation of Königsberg [the present Kaliningrad]. Expecting important increase of enemy shipping movements in area Bight of Gdansk." Good news, but no enemy targets appeared in Marinesko’s periscope. In the early morning of January 30, Marinesko summoned his officers and together they decided to try their luck at the Hela peninsula in the Bight of Gdansk. The independed-minded submarine commander, who rarely made use of the Boechta radio equipment aboard the S-13, now again failed to inform his superiors of his new position.

That same night, around 19:10 hours, the lookout of the S-13 noted lights on the coastline. Marinesko was convinced that those lights belonged to German vessels on their way to the west. He was determined to launch a surface attack although this was completely against the conservative Soviet views of those days. These views were simple: a submarine attacks when submerged. A surface attack, however, had many advantages. Making use of the diesel engines, the submarine was faster and more manoeuvrable. Moreover, the torpedoes could be launched with greater accuracy. Of course, the disadvantage of a surface attack was that the submarine could be noticed more easily by the enemy. That however was not Marinesko’s main concern because it was dark now and the fog and snow gusts would hide the S-13 from any lookout. Furthermore, Marinesko knew that the Germans did not have possession of radar planes and were desperately short on escort vessels. In between two snow squalls, Marinesko noticed two vessels, a large ship and a small one. The submarine commander was convinced that it was an evacuation ship and an escort minesweeper. This belief was almost correct, for the two were the Wilhelm Gustloff, packed with German refugees and her escort, the destroyer Löwe. The S-13 kept following the small convoy, as the submarine continued to hover between the coast and the enemy ships. In this way, the surfaced submarine was hardly visible to the Germans.

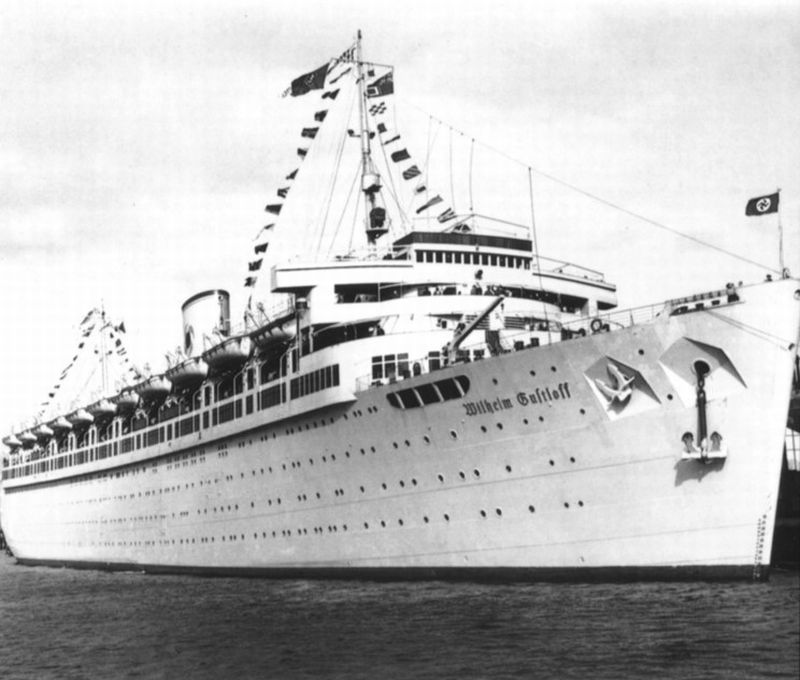

The Wilhelm Gustloff, the first large victim of Alexander Marinesko and the S-13. Source: Maritimequest

It took the S-13 nearly two hours to reach the right position for the attack. The enemy vessels began to round the Stolpe Bank, which they passed on the port side, the same on which the S-13 approached the German ships. He had the torpedoes set at a running depth of three meters. At 21:00 hours Alexander Marinesko gave the order to launch the four bow torpedoes. The first, third and fourth torpedo left the tubes but the second got stuck in the tube. While the torpedohandling crew were feverishly attempting to defuse the jammed torpedo, the other three hit the Wilhelm Gustloff on the port side. Marinesko kept the S-13 just above the surface while watching how the stricken ship lurched and began to heel. As soon as he was certain that the ship was going to sink, he had the conning tower cleared to dive as soon as possible to escape the escort vessel. While the torpedohandling crew defused the jammed torpedo, the S-13 was able to get away. It was only during the following night, that the S-13 surfaced and signalled to the Baltic Fleet at Kronstadt and home base Smolny that they had sunk a passenger ship of 20,000 tons with three torpedo hits. However, there was no source available that could confirm this and in Kronstadt they had the impression that Marinesko was exaggerating. Marinesko, who was unaware of the name of the ship he sank and of the magnitude of the disaster, caused by the sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff resumed his war patrol.

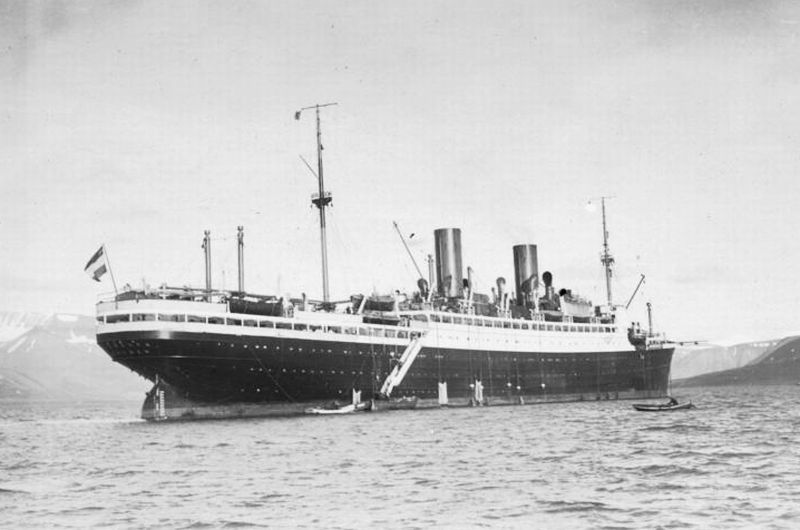

On the thirtieth day of the patrol, February 9, 1945, Alexander I. Marinesko struck again. From January 31, he remained in the vicinity of Stolpe Bank. Around 22:00 hours, the propellor noise of a convoy was detected on board the S-13 and a few lights were observed from the conning tower. Marinesko had his crew take up action stations and prepare for a surface attack of the convoy. However, one of the escort vessels approached the Soviet submarine, and the S-13 had to make a crash dive. It took more than an hour for Marinesko to manoeuvre the S-13 in a suitable position for an attack. This time he opted for a surface attack with both of his stern tubes so that the S-13 could make a quick escape after the attack. Both the stern torpedoes were launched on the largest ship in the convoy and both hit the ship. Marinesko saw the projectiles explode against the vessel’s hull, after which it sank immediately. Without knowing, the submarine commander had sunk the 17,500 ton passenger liner Steuben, which was packed, just like the Wilhelm Gustloff, with German refugees.

The Steuben, also torpedoed by Alexander Marinesko. Source: Bundesarchiv, N 1572 Bild-1925-079 / Fleischhut, Richard / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Within ten days, Marinesko had sunk two of the largest German ocean liners, killing 14.000 victims. This made him the tonnage king of the Red Fleet, and it had proved him right where his attack theories were concerned and had thereby, according to him, rehabilitated him after the incident in Turku. On February 15, he moored at the base Smolny in Turku. Here, Kapitan 1 ranga Orjel told him that, according to the Swedish newspaper Stockholm Tidningen, he had sunk the 24,000-ton Wilhelm Gustloff. Orjel also told him the name of Steuben the second major victim of the S-13. According to Orjel he was going to get the credit for both achievements.

On April 20, 1945, the headquarters of the Baltic Fleet published a list of awards, bestowed to navy personnel in the first three months of that year for bravery during combat actions. The S-13 was awarded a collective award, which made her a Red-Banner boat. This was a great honour and the S-13 was only the second Soviet submarine to receive this recognition. Marinesko, however, was disappointed. In his opinion, the S-13 should have become a Red-Guard ship, an award, received by only sixteen Soviet warships during the entire Second World War. Each crew member of the S-13 was awarded one of two classes of the Order of the Great Patriotic War, millions of which were awarded in the war. Marinesko was not satisfied. In his view, he should have been proclaimed Hero of the Soviet Union, but the five-pointed star was denied to him. He even was denied the second Order of Lenin but had to accept another Order of the Red Banner. Moreover, the citations about the awards of the S-13 and her commander did not mention the sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff and Steuben. This was a clear indication that the Military Council was not convinced that these ships were sunk by the S-13. This enraged Marinesko. While the S-13 was under maintenance, he spent his time in Turku, mostly drinking and arguing with everyone who dared to find any fault with his submarine. He never tired of telling his superiors that he had sunk German vessels with a total of 42,144 tons and so killed thousands of fascists. However, nobody listened to him.

To prove himself right, Marinesko started writing a book, with the title: "An analysis of torpedo-attacks of the S-13." He considered this as a future instruction manual for the Soviet submarine Fleet. He did not suffer from false modesty and felt that his experience and successes entitled him to advise on how to handle a submarine attack. As soon as the naval command had officially confirmed his successes, the rest of the Soviet navy would know also. He was the greatest, the tonnage king. In his book, he criticized the technical deficiencies and tactical inferiority of the Soviet submarine fleet. When Marinesko had his manuscript read by some of his colleagues and friends before submitting it to Orjel, they warned him that his comments on equipment, tactics and authority structure might be used against him. Shortly, the Soviet Union would not be needing submarine commanders like Marinesko any longer and Stalin and his secret police had already begun to arrest everybody with a semblance of dissent among the armed forces. Marinesko however, ignored all warnings and just as his friends had feared, his analysis provided ammunition to all of those who were envious of his successes, in particular the NKVD.

Marinesko made one last trip with the S-13. At the beginning of May 1945, he was ordered to sail and on May 9, the crew celebrated the end of the Second World War and the victory of the Soviets at sea. Stalin did not trust his Western Allies and kept his armed forces in readiness for a while.

Definitielijst

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- Great Patriotic War

- Soviet and Russian term for World War 2.

- Offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

After the second World War

It became an obsession for Marinesko to make the naval command recognize that the S-13 had sunk the Wilhelm Gustloff and Steuben. He made enemies and lost friends with it. He pestered staff officers with his demand to reconsider the list of awards and bored those around him with his moaning about injustice. In September 1945 Marinesko was relieved of his command of the S-13 and was given command of a minesweeper. Furious and drunk he refused to accept command of the ship and was demoted two ranks to starshyi leitenant. In November 1945 he was discharged from the naval service due to an indifferent attitude towards the military service. Marinesko applied for a job in the Soviet merchant navy, but his NKVD file appeared and he was rejected for not being reliable. In January 1946 the former submarine commander, bearer of the Order of Lenin, twice the Order of the Red Banner and various victory- and campaign medals was put ashore for good, and he got a job as a warehouse manager in a building materials company in Leningrad.

Life in Leningrad, just after the war, was hard and drab. The city was largely in ruins due to years of German siege. There was a great shortage of commodities and foodstuffs and the black market was booming as never before. Bribery and corruption formed part of everyday life. Marinesko was hurt and embittered by his discharge from the navy. Unable to find a seafaring job and drinking heavily he might easily, because of his background as a street urchin in Odessa, have taken up his role under the corrupt civil servants and profiteers, but he did not. He even accused the director and some workers of the state building company that employed him, of accepting bribes for the delivery of building materials to party officials who had expensive villas built outside Leningrad. The director waited for a chance to get rid of Marinesko.

Tons of damaged and rejected concrete blocks and bricks were piled up in the company courtyard. Marinesko suggested to the director that these materials be divided among the labourers of the company as a New Years gift. He supervised this distribution. A tattletale reported the distribution of the materials to the police. An inquiry led to the building company and its warehouse manager Marinesko. The director denied his authorization of distributing the materials among the labourers and Marinesko was charged with theft of state property and arrested. He was brought before a Special Council, consisting of three KGB officials who were specialists in political misdemeanours. Marinesko was found guilty and sentenced to three years in a labour camp in Kolyma, Siberia. It is not known which part of Marinesko’s secret police file had been involved here, but his judges must certainly have been familiar with it when they delivered their verdict on the former submarine commander. Kolyma was known as the most terrible of all labour camps, where most political prisoners were sent and rarely returned.

However, Marinesko’s fighting spirit was not yet broken, and during the journey of 10,000 kilometres with the Trans Siberian Railway in a prisoner carriage, in 1949, his natural leadership and decisiveness were evidently present. Every carriage had a leader appointed by the guards. In Marinesko’s carriage, this was a prisoner, sentenced to 25 years in labour camp for collaborating with the Germans by providing them with information about citizens. Among other things, the carriage leaders were appointed to distribute food rations in the carriages. After his sentence, Marinesko told some friends: "The bastards started to terrorize the rest of us. That scoundrel and his mates gave themselves two mugs of soup and all the others only one and not even filled. Soon enough I realized that in this way I wouldn’t see the Pacific Ocean and that I had to take action. Eight of us in the carriage were sailors and it didn’t take much effort to organize something. When the soup arrived and the rascals started the distribution I signalled and we attacked. We gave the fascist friend such a beating that he barely lived. But it did help. I appointed as carriage leader a fellow who got five years for pinching a can of meat while unloading a ship. When the head guard realized that we had no intention of escaping he did not bother about it and ignored what had happened. In that way, we reached Vladivostok."

With this typical toughness and state of mind, Alexander Marinesko was able to survive his penal period. He was able to convince the camp authorities of the fact that his group of eight sailors would form a formidable team of dock workers. The sailor from Odessa managed to have his team of eight sailors employed in the East-Siberian port Nagajevo where they loaded and unloaded ships that transported supplies for the mines in the labour camps. In this way, Marinesko managed to keep his men and himself out of the mines and alive. Marinesko was relieved in October 1951 without knowing why. After the long journey back to Leningrad, he was employed as a topographer and in 1953 as department head in a factory. He also was allowed again to rejoin the Communist party, which was a clear sign that he was forgiven for whatever it might have been that caused his exile to Kolyma.

During the period that Alexander Marinesko spent in Siberia, his most loyal friends quietly started a campaign for his release and rehabilitation. Little by little, they began to achieve something. The breakthrough came in 1960 with a television program about the sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff for which Marinesko was given the credit. Shortly after this, as an off-duty officer, he was reinstated to his former rank of Kapitan III ranga and given the corresponding pension. The Central Navy Museum in Leningrad honoured him for his achievements. In the museum, visitors can read that:

A.I. Marinesko commanded the S-13 between 1943 and 1945. The submarine sank three enemy vessels. On January 30, 1945, the S-13 attacked the Nazi ship Wilhelm Gustloff which was over 24,000 tons. Three torpedoes hit the target and the enemy vessel sank. Several thousands of soldiers, sailors and officers were on board the ship, used by the Hitler gang for the evacuation of Dantzig. There were also on board several military personnel of the submarine service.

Though the statistics were not entirely correct, this narrative brought Marinesko the public recognition for which he had been waiting, for over 15 years.

In October 1963, at the annual reunion of the Baltic Fleet in Kronstadt, Marinesko’s friends organized a ceremony in his honour with all the associated traditional protocols. After the ceremonies, they gave him a standing ovation. At last, he was given the honour due to him. Three weeks later he died of cancer in Leningrad.

In 1990 Marinesko was posthumously awarded the honorary title of Hero of the Soviet Union on the occasion of the forty-fifth anniversary of the Soviet victory in Europe. He was given a momument in Kaliningrad, [the former Königsberg] in East Prussia and a mausoleum in Odessa. To illustrate the extend of his rehabilitation, the submarine museum in St. Petersburg was named after him.

Definitielijst

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Odessa

- Organisation of Former SS-members. Secret organization of and for former SS-members. Organised new identities and housing abroad after the war.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Information

- Article by:

- Peter Kimenai

- Translated by:

- Cor Korpel

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related books

Sources

- DOBSON, C. e.a., De ondergang van de Wilhelm Gustloff, Elsevier, Amsterdam/Brussel, 1979.

- MALLMANN-SHOWELL J.P., Das buch der deutschen kriegsmarine 1935-1945, Motorbuch verlag, Stuttgart, 1995.

- POOLMAN, K., Allied Submarines of World War Two, Arms & Armour Press, London, 1990.

- www.wilhelmgustloff.com

- www.militaryhistoryonline.com

- www.en.wikipedia.org

- www.de.wikipedia.org

- www.uboat.net

- www.rusnavy.com

- www.maritimequest.com

- www.shipsnostalgia.com

- With thanks to Anne Palmer for her editorial work.