Preface

Emile Tielman was born on February 5, 1916 in Mojokerto, on the Indonesian island of Java. After World War II ended in Indonesia as well in August 1945, Emile went to the Netherlands in 1946 to recover from malaria and beri-beri. That year he studied meteorology and returned to Indonesia in 1947 as a meteorologist.. After he got married in 1960 he emigrated to America. There his daughter Ria was born. She studied, together with her friend Roberta, called Bobbi, at Drexel University.

In 1987, for her history studies, Bobbi received the assignment to interview a prisoner of war from World War II and present the result to her fellow students. She then asked Emile Tielman if he would write down his experiences as a prisoner of war and survivor of the Junyo Maru tragedy. He did and below you can read the precipitate of his handwritten letter to Bobbi.

Emile Tielman was retired in 1979 and passed away on Januari 4, 1998.

The Letter

Palm Bay, May 9th 1987

Dear Bobbie,

Thank you for your letter, the birthday congrats and sending me your love. The letter makes me very happy and gives me the stamina and inspiration to work on your project.

Let me start with answering your guestions. In the 1930's it became obvious that Japan tried to expand its territory by attacking the mainland of China in 1937, Indo China and intended to attack the Dutch East Indies, mainly for its rich resources like oil, pewter, iron ore, rubber and so on. Shortly before WWII, the Netherlands closed a pact with the U.S.A., purporting that if one of the two countries was attacked by an agressor the other partner would declare war on the agressor.

Holland was overrun by the Germans (May 5th 1940) and after that date, the Dutch East Indies, presently called Indonesia as a part of of Holland in South East Asia, was on its own.

Right after the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor (7 Dec. 1941) the Governor General (Representative of the Queen of Holland) of the Dutch East Indies declared war on Japan, on the same day the U.S.A. declared the war on Japan.

The attack on Pearl Harbor destroyed the U.S. fleet in the Pacific and all of South East Asia laid open for the Japs, including Australia. They invaded the Philippines, Birma, Guam, the Malayan Penninsula and the end of Febr. 1942, Singapore, the main fortress on the Penninsula, fell.

The British Navy lost their 2 mightiest battleships, The Prince of Wales, and the Repulse, so that rampart was gone.

The Dutch Navy suffered losses too and after the fall of Singapore only one battleship was left, the Karel Doorman. There was no air support, most of our planes were shot down and what was left was evacuated to Autralia, because the Dutch East Indies was considered a lost case.

Finally the Karel Doorman was sunk by a Jap. submarine and nothing was preventing the Japs to land. That happened in the morning of March 6th 1942.

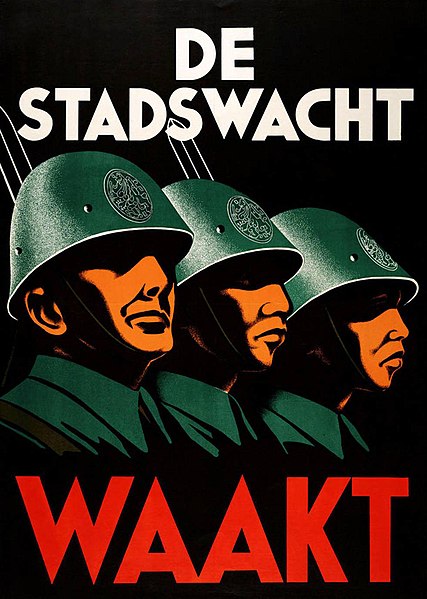

Stadswacht

Now I go back. When the war broke out (Dec. 8 th 1941) , every eligible man was drafted by the military, except the men working for services essential to the war effort. I worked for the meteorological service and was exempt from military duty. Employees of the met. service and others, also exempt from military duty, erected the "Stadswacht", translated "CivilGuard", a semi-military unitThe members were not really soldiers, but civilians who trained once a week, with the aim at preventing shooting and to maintain law and order where necessary. We carried arms but were not equipped like a professional army. I was stationed in Batavia, the capital of Java.

During the night of March 5th I was housed, with other members of of the Stadswacht, in the headquarters of a big oilcompany. Nobody slept and when we heard machinegun fire we know that the Japs had landed. The sound of gunfire came nearer and nearer, till it reached the building. We were instructed by our commander to wear a piece of white cloth around our right arm and outside the building was a white flag because resistance was useless. Then for the first time did I see Jap. soldiers. A Jap officer with half a dozen soldiers entered the building and asked for our commander, whom he addressed with the following words "For you the war is over". He then called in his unit, who dispersed in the building.

That was my first day of captivity, to end Aug. 26th 1945 in the jungle of Sumatra

Early in the morning of March 6th we were herded tohether in the parking lot of the building and marched off to a prison. This prison was built shortly before the war as a model prison of the Dutch Government. It had a very spacious court-yard and the side across the entrance was built in a semi-circle and divided in 3 parts. It was called circle block I , II and III. The Stadswacht was housed in the centerpart Circle block II. The rest of the prison consisted of 1 and 2 persons cells. The sanitaire conditions were fair. Gradually the Nips (Japs) were picking up the European males and the prison was filling up and when the prison was filled to capacity its occupation excisted of lawyers, doctors, high ranking executives, heads of business firms, young kids, too young to be drafted.

The Jap. commander, an economist treated us well and was very lenient.

He left the management of the internees to the the commander of the Stadswacht, we were allowed to receive packages from relatives once a week, even relatives were allowed to send food daily. Early in the morning the native guards unlocked the cirle block and the cells, and the inmates could do what they wanted. Play cards, exercise, read, you were free to do what you wanted.

730 Tokyo time we were locked in for the night, that was the daily routine.

The Hungarian Dance Band of the biggest hotel in Batavia was also picked up, they were allowed to bring their instruments with them. Once a week they performed for us and the Jap. commander liked it so much that he attended the show reguarly. He permitted us with X-mas to build a primitive stage and perform comical skits. He attendad this show also and had the greatest fun.

The food was eatable. In the morning coffee with a chunk of bread,baked of cornflour, lunch consisted of rice with a kind of soup, dinner was the same course.

We were even allowed to plant fast bearing fruittrees allong the walkway leading from from the entrance of the prison to the circle-block, and every morning a detail was led out of the prison into the space surrounding the prison upto the prisonwall which encircled the whole prison. I was one of the detail and we raised tomatoes, and al kind of vegetables. The fruit and vegetables were a nice variation of the menu, and working outdoors broke the monotony.

Bandoeng

This routine lasted till Febr. 14th 1944. On that day our campleader was summoned by the Jap. commander and was told that the prison had to be evacuated and al the inmates were to transported to Bandoeng, a town were I lived for 15 years and where my parents lived.

During the night of Febr. 15th we were marched to the station. We boarded the train in the dark and left Batavia to arrive in Bandoeng after 6 hours. We were housed in a vast complex of militairy baracks, already occupied by males picked up in that city and I was united with my father who was picked up after 4 weeks since the Japs. occupied Java.

Again the same routine. You could move freely in the compound, talk to friends or do what you wanted to do.

This internment differed from the one in Batavia because work-details were send out to work on various jobs in the city, what never happened in Batavia.

One morning when I was lined up for voluntairy duty, a Japanese cook needed 4 men. 2 to assist him in the cooking, and 2 to chop wood to keep his cookingfire going. I volunteered for the woodchoppers job, and selected me. That was the best job during my internment, because for a Jap. the cook was an exception. He was gentle and apparently, because he was always among food, was also generous in giving it away.

It was a healthy job, the whole day chopping wood, no smoking because cigarettes were not available, all the good food you could eat and the result was a muscular body.

The cook also allowed us to take the leftover food to the camp, what I did as a nice meal for my dad.

As usual this didn't last very long. Mid July 1944 the ex-Stadswacht commander was summoned by the Jap. commander and informed that the Stadswacht was now considered a military unit, because we were carrying weapons when we surrendered. Therefore the Stadswacht was to be returned to Batavia, and interned in a P.O.W. camp.

This time we were marched off in daytime to the station and when I looked back I waved my dad good-bye, never to see him again.

Back in Batavia we were housed in a vaster complex of militairy barracks than the one in Bandoeng and when we arrived there was already a considerable amount of P.O.W.'s. The routine was the same, you had freedom to move in the camp, and there were also details send out to work in the city. The big difference with the Bandoeng camp was that this camp was a transit camp. Drafts of P.O.W.'s were transported over sea and it was not known where to. It was mid year 1944, the Americans were advancing in the Pacific, but still we were treated fairly well. The doctors in the camp still had a limited availability of drugs and were treating the sick P.O.W.'s, and you must be real sick to be exempted from a draft. A sick man, diagnosed to have dysentery, was sure to be exempted. Irt was known that many P.O.W.'s just to dodge a draft, went to a sick person diagnosed as having dysentery, took a samp of his excrement, and contaminated themselves consuming it. Another difference of this camp with a civilian camp was the order that every P.O.W. must have his head shaved completely bald. So was my head and for the first time in my live I have a bald head. I must admit it felt good.

Then Sept. 13 th 1944 came the order: The Stadswacht had to be ready for transport.

Junyo Maru

After the order for transport was known, wild rumors were circulated through the camp. One was transport over sea, another that we were transpoted further inland, but not the definite destination.

Transport over sea meant 99% disaster. The American fleet had won supremacy in the Pacific. So did the British navy in the Indian Ocean. Transport further inland meant that we could sit out the war. What really our destination was became clear a few days later.

Early in the morning Sept. 14,sup>th the Stadswacht was lined up in the yard and marched off to the station. We boarded the train and bets were made. Would the train travel to the harbor of Tandjong Priok of inland? It traveled to the harbor, and now we knew. It was transport iover sea, where to, we didn't know.

Particulars about boarding cargo, departure will follow in a seperate article, what I write down is my personal experience.

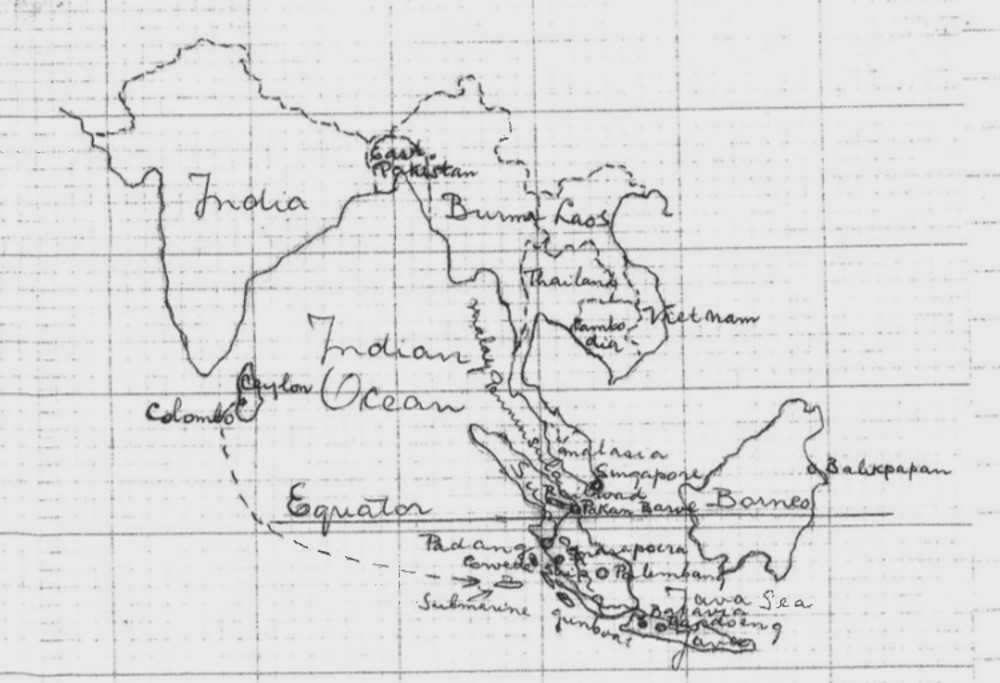

Boarding ws finished late in the afternoon Sat. Sept. 14 th, the ship stayed in the harbor. Sunday the 15th and Monday the 16 th sailed out of the harbor early in the morning. It sailed through Str. Soenda, and when the west-coast of South Sumatra became visible the ship followed the coast-line, but stayed 15 miles offshore.

All went well during daytime, also during the night, and it became Tuesday morning, Sept. 17 th, noon and the end of the day was nearing.

Than it happened.

It was around 5.30 P.M., we just had our eveningmeal and our ration of water and while I was screwing the cap on my watercanteen, I heard a man shouting at the railing: "Look, a f.... torpedo."

Then a deep muffled explosion.

The lid, covering the front hold flew open and I saw 5 bodies flying in the air, clearly silhouetted against the sky as if released by a giant spring. It didn't dawn on me, that we were hit, till the second explosion aft (???) of the ship. I looked over the water and saw the surface rising rapidly, that meant the ship was sinking.

Panic was now everywhere, men on deck were fighting to get to the railings and the ones who were below deck in the holds were screaming, fighting and struggling to leave the holds.

The ship had 3 army-trucks anchored on the upper deck and a soldier who laid underneath one of the trucks for shelter was caught under the rear tire of the truck with his hand, when the truck shifted by the explosion. He tried to free him frantically. I will never know if he succeeded. I fought my way to the railing and when the deck was 3 feet above water, jumped and swam away from the ship, as far as possible, to get away from the sucking when the ship went down.

I looked back and saw that the ship was broken in half, the bow and stem were protruding as giant triangles, but became smaller and smaller while sinking, till they vanished complete.

The ocean was now covered with bodies, dead and alive and all kinds of floating debris, a few rafts were floating overloaded with castaways but no lifeboats.

The sun dipped under the horizon and it was getting dark.

All I did was treading water, with no direction to go. It was pitch dark now, the sky was overcast. The screaming started. Cries in Dutch, English and Malayan language for help, many in agony, the sharks had found their prey.

The ship carried also a cargo of oil-drums when the ship went under. They floated free and by the swell of the ocean were bouncing against eachother. The result was such an eerie and ominous sound and with the screams for help all around, not to be imagined.

Then the notion that you were treading water in the ocean with hundreds of feet of water below you, what only meant: tread water of drown. I prayed for strength and not to be attacked by a shark and somehow I survived the first night.

The next day, after the sun was up, all you could see were floating bodies, debris, but no raft of life-boat in sight.

As i wrote before, by voluntering for woodchoppe in Bandoeng and later in work-details in Batavia, had I developed a very strong body, but I started to get tired now.

The day went and the second night came. By now I was fatalistic and ready to give up. But there was an inner-voice saying: "Don't give up, you are too toung to die." I was then 28 years old. By some miracle I survived the second night and at dawn the next day I saw the ship , a corvette, what was meant as escort for the cargo-ship. I was hallucinating and when I spotted the ship thought that I saw a mirage. It wasn't and to my greatest joy it was sailing in my direction. I thought that the look-out saw me and the ship tried to save me. But it changed its direction and made a turn of 900 at about 200 feet away.

It then laid still in the water to haul the survivors of a raft on board. I was really panicked. This was my last chance to survive. If I missed the ship I would certainly drown. I started swimming towards the ship and was approaching it foot by foot and had about 60 feet to go, when the ship started to move. It had taken in all the survivors on the raft and went on its way.

I tried to reache the ship with my last efforts, but it had gained speed and I still was 10 feet behind it. Luckily a Jap sailor saw me, with a rope in his hand. He threw me the rope, it fell short and I couldn't grab it. He threw it a second time and I prayed:"God let me catch it. This is my very last chance." I caught the rope and the sailor was hauling me in, till I was above the propeller of the ship. I felt it churning under my feet. The sailor saw the danger, pulled me awayand hauled me on deck. I was safe, after floating ± 38 hrs in the ocean.

All I could do was sitting on the deck, with my head between my knees, and let the world go by. Then somebody shook me vigirously. I looked up and saw a medic with a bottle of iodine in one hand and a thin cotton swab in the other. He pointed to my legs. I looked at them and understand what he meant.

I had a finger-long wound on my left leg, apparently caused by a piece of floating debrissa by the stay in the salty water, bitten out so deep that you could easy lay your index-finger in it. He dipped the swab in the bottle and desinfected the wound. I was oblivious to the pain, all I wanted was to rest.

The ship continued its course. Survivors who could be reached with ropes were hauled on deck, the ones who couldn't be reached were left alone.

There were floating corpses everywhere you looked, you saw the agony in the eyes of the unlucky ones out of reach of a saving rope, but you were so apathetic, that only this thought crossed your mind: "Thank God . It's me on deck and not in the ocean."

The ship was sailing a straight course, it never diverted or altered its course for a floating raft or survivor and late in the afternoon it sailed into the harbor of Padang where it docked. We were put ashore and herded into a big warehouse where we were fed and could rest. I stretched out on the bare floor and slept immediately. Army trucks arrived after a few hours and we were driven to a vacated prison in the city, and unloaded.

This is were we had to spend the night. The conditions in the prison were unhuman. No sanitaire facilities at all. The drainage gutters were overflowing with human excrements and maggots, the stench of urine was nauseating and your bed was the bare floor of the cell, crawling with lice, no opportunity to take a bath or wash, nothing, not even the bare essence.

But you were so apathetic that nothing could matter any more. I slept through the night, oblivious of the lice.

Pakan Baroe

Early the next morning we were loaded on army trucks and the yourney across Sumatra to Pakan Baroe begun. We crossed the Equator,and saw the monument, erected by the Dutch Government, on the spot where the imaginary Line crossed the road.

We reached our camp in Pakan Baroe at dusk and saw other camps with P.O.W.'s who arrived earlier.

The conditions were harsher . The camp consisted of a wooden structure, erected in a clearing in the jungle, no sanitaire facilities or hygiene, nothing. The food was not sufficient and the labor exhausting. The prisoners had to build a rail-road and as the rail-road progressed we had to evacuate the original camp, to be housed in another. The Japs didn't celebrate the sundays, so you ere working 7 days a week and that took its toll. Many survivors, alreay weskened by the ordeal, died and our numbers were depleted considerable.

I contracted malaria within 2 weeks, so did others.

Christmas 1944 came. I remember that we found a little tree in the jungle, that resembled an evergreen. We took the tree to camp and with rags of clothing made tiny bows that resembled snowflakes. That was our X-mastree. After X-mas, 1945 set in.

The malaria attacks occured more frequently. I contracted Beri-beri, a disease caused by complete lack of vitamins, whereby the flesh of the body swells like a balloon and became so weak that I was sent to the main camp, at the beginning of the rail-road. That was July 1945. In that camp I made myself a pair of wooden clogs and one day scratched the inside of my right foot at the ankle. The tiny scratch grew out to a tropical ulcer and because my body didn't have the least resistance to fight the infection, it became one big festering sore. We still had our own doctors in the camp, no medicine or antibiotics at all. The only way to clean the wound was with maggots. Flies laid there egg in the wound, it was then wrapped with rags desinfected by the sun and after a week when a doctor took off the bandage, the maggots jumped out of the wound. But the wound was clean.

I then contracted dysentery. Luckely it was benign, if you contracted amoeb-dysentery it meant certain death.

I was the so weak and sick that I only could move with the greatest effort and was waiting for the end.

Freedom

August 1945. Rumors were circulating in the camp that the war was over because an unusual activity was observed in the Jap quarters. Papers were burned, their attitude towards us changed and more food came into the camp. Then August 26 th our camp commander was summesied by the Jap commander and was informed that Japan had lost the war and he now surrendered to the Dutch.

When the news became officially known in the camp I felt a great sence of relief and joy. I had made it.

Now relief-goods were parachuted into the camp by the British Airforce from Singapore, medicine, supplies, clothing. Due to the good food and the proper medicine I recovered speedily.

The whole camp was evacuated in Nov. '45(???) and flown to Palembang, where we were housed in a secured part of the city, what we named 'The Concession'.

We could write letters now. I wrote my mother that I was alive and survived the war and asked of my father came home already. She wrote in her answering letter, that my father died in the camp March 25 th 1945.

When we celebrated X-mas and we were all together, we counted how many were left of the draft that left Tandjong-Priok the 16 th of Sept. '44. The count came to 79.

From the 6500 men who left Java that day 79 survivors were left. I am one of them.

We could not leave Palembang, till after a few months. There was no government established yet in Java, there was fear of hostilities of the native population and finally in Febr. '46 we were allowed to enter Java. I was reunited with my mother and sister, luckely they were in good health.

I couldn't resume work, I still had malaria and beri-beri and April '46 was send to Holland for 1 year to recuperate.

I took a course in meteorology during that year, and returned April 1947 to the Indies as a meteorologist.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Information

- Article by:

- Leo G. Lensen

- Published on:

- 09-05-2022

- Last edit on:

- 19-08-2022

- Feedback?

- Send it!