614th Tank Destroyer Battalion

"The 614th was activated at Camp Carson, Colorado, in 1942. I am one of its few original members," wrote sergeant Gordon B. McGinnis of B company to the newspaper of his native state.[1] This letter was published on 3 March 1945 in The Ohio State News. On that day, the 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion was in France, where the unit was recovering from the fighting that it had experienced in the previous period. However, the 614th was a remarkable unit, because in contrast to to other American combat units, it consisted of solely black soldiers.

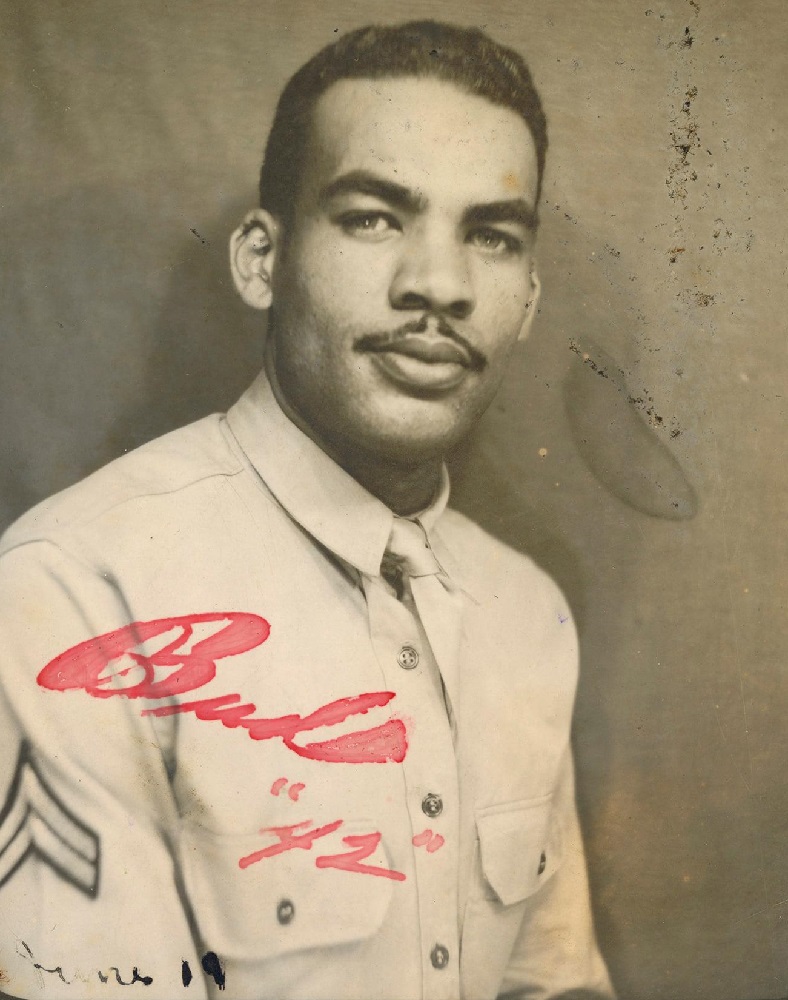

A photograph of Gordon McGinnis, here with the rank of Corporal. Source: Gordon McGinnis Papers, AR784, 1, 7, Special Collections, The University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.

Segregated tank destroyer battalions

On July 25 1942 the 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion was activated at Camp Carson, Colorado. As mentioned previously, the unit was made up of only black American soldiers. This was remarkable, because there were few combat units where black soldiers could serve. The American society was segregated, which meant that black Americans were separated from white society. There were special drinking fountains, houses, and toilets for African Americans. Due to the then present notions about race and descent, were most African American soldiers were assigned to service- or support units. It did not go without saying that there would be segregated combat units, and even if there would be, then it was the question if they would be employed for their intended task.The American tank destroyer were originally intended to stop the German tanks. The misconception was that the German Blitzkrieg consisted of a massed tank attack. The tank destroyer units were formed as a reaction upon this, with the thought that a concentration of enough anti-tank weapons would manage to stop the advance. Of the newly established tank destroyer units, there were also two segregated battalions: The 846th Tank Destroyer Battalion and the 795th Tank Destroyer Battalion. However, both units were never deployed, but deactivated after a time and converted to service units.

A three-inch gun of the 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion during a training exercise in England. Source: National Archives and Record Administration

Not fit for modern warfare

In February 1944 Congressman Hailton, who had served in the segregated 369th Infantry Regiment during the First World War, asked with several others why various black tank destroyer battalions and artillery units were broken up. The answer of the Secretary of War Henry Stimson as: "It so happens that a relatively large percentage of the Negroes drafted into the Army fall within the lower educational classifications, and many of the Negro units have been unable to efficiently master the technique of modern weapons."[2]

For the 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion, it was also unclear if they would see action at the front. They were armed with guns that had to be towed by halftracks, while other units were armed with dedicated tank destroyer vehicles, such as the M10 or the M18 Hellcat. These self-propelled guns had the advantage that they were much more mobile than the towed guns.

After the unit had completed its training, the battalion was transferred in July 1943 to Camp Hood, Texas, where they were employed as training troops. They had to perform special scenario’s for the nearby Officer Candidate School or carry out demonstrations. This period lasted until December 1943, when they finally received the orders for additional exercise, intended for overseas deployment.

This training period lasted until April 1944, but in June it appeared suddenly that the unit had not yet completed its training . Specifically, they had not yet finished their indirect firing training, through which targets could be engaged that were not directly within the line of sight. This was a setback for the soldiers, but due to their extra training, they felt even more prepared for their task. On 27 August 1944 they finally left America.

To the front

In October 1944 the battalion arrived in France. There the tank destroyers were temporarily stationed in the vicinity of Cherbourg. It was an uncomfortable period, because they wanted to go to the front and their lodgings were not good. Gordon McGinnis wrote about this period: "Those were days of sleeping in pup tents, with wooden floors; and it rained nearly every day; mud was terrible."[3]

But finally orders were received to proceed to the front. The 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion was attached to the 95th Infantry Division, and there they were employed in combat for the first time. During their service at the frontline the unit experienced various shellings. Gordon McGinnis wrote about them: "It was not nothing to hear the familiar sound of a German 88 on its way in and the debris flying when it went off."[4]

During a shelling of C company the vehicles of the first platoon were abandoned. Lieutenant Walter Smith and staff sergeant Christopher Sturkey managed to distinguish themselves at this time, because they managed to rally the men and bring the vehicles to safety.

On 7 December 1944 the 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion was attached to the 103d Infantry Division. Although the battalion received a cold welcome, this swiftly changed. The reason for this, was the battle of Climbach.

A three-inch gun of the 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion with the crew around of it. Source: U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center.

The Battle of Climbach

On 14 December a task force was prepared, consisting among others of a reinforced infantry company, a platoon of tanks from the 47th Tank Battalion, the third platoon of C Company of the 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion. Lieutenant Charles Thomas went along with the platoon, although he was not directly needed as a company commander. The task force was commanded by Lieutenant-colonel John Blackshear.

The goal of this task force was to seize the strategically situated town of Climbach. The Americans had been told by prisoners that the village would be poorly defended. On the road there the taskforce was shelled and Lieutenant Charles Thomas proposed to ride at the head of the column. When he went over the last hill to Climbach, his vehicle was immediately knocked out. The road had been mined and German antitank guns were aimed at the road. Despite the resistance and his injuries, Lieutenant Thomas ordered two of his four tank destroyers to take up position.

The tank destroyers were brought forward, and they positioned themselves in the open field near Climbach. This was a dangerous position, because the German guns clearly had them in their sights, and it didn’t take long before crew members were injured or killed. To make matters worse, German infantry attempted to overrun the two crews. With the help of a platoon of American infantry and the use of nearly all crew members acting as infantry, this attack was stopped. Meanwhile, a corporal ran between the two guns to aim and fire them.

All this time, Lieutenant Thomas remained in the field to encourage his men. He refused to leave the battlefield until another officer was present to take over command. Only after lieutenant George Mitchell had arrived, did he allow himself to be evacuated. After the attack was repulsed , Mitchell gave the order to bring the two remaining tank destroyers forward. They were deployed, but swiftly one of them was silenced by the German guns. The remaining cannon, under the command of Sergeant Dillard Booker, kept firing until the end of the day. Meanwhile, they almost ran out of ammunition, but at the last moment a driver of the platoon brought up a new supply.

While the black tank destroyers battled with the German forces in Climbach, the American infantry, minus the platoon that protected the tank destroyers, made a flanking maneuver and approached the village. A fierce battle ensued, but they managed to take the village. Once the fighting was over, it wasn’t them that took the village, according to the American infantry, but had the black tank destroyers of Third Platoon, C Company, had managed to do this.

The ferocity of the fighting becomes clear from the fact that the platoon lost three of its four guns and that half of the platoon was wounded or had perished. Still, the actions of the black tank destroyers impressed the white soldiers of the 103rd Infantry Division. They were praised for their courage and what they had managed to do. From a disadvantageous position, they took on an entrenched enemy. At Climbach the black tank destroyers had shown what they could do. They had won the respect of the white soldiers, and as McGinnis wrote: "we’ve been battling right along with the white boys of the division ever since."[5]

Lieutenant Charles Thomas was recommended for the Distinguished Service Cross, which had been just once awarded to a black soldier since the end of the war. Meanwhile, the third platoon was recommended for the Distinguished Unit Citation, a group decoration. They would be the first black unit that would get this award during the Second World War.

Winter on the western front

The relation between the white and black soldiers improved immediately, and the black tank destroyers would remain with the 103rd Infantry Division for the rest of the war. In December 1944 the Ardennes Offensive started, which forced Allied soldiers in the Alsace to move to the north to prevent the German breakthrough. When the Ardennes Offensive threatened to become a stalemate, the German senior staff looked for places elsewhere to break through . They chose operation Nordwind in the Alsace, because the lines were thinner, since many troops had been rushed to the north.

For the men of the 103rd Infantry Division this posed a risk, because they were in an advanced position and were in danger of being surrounded. Therefore it was decided to move the division back to the west in January 1945. Retreating in a blizzard, the division lost part of their motor pool and accompanying material. Also, the 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion lost several weapons. Three guns and six halftracks were abandoned and destroyed. The retreat was a costly expedition for the Americans.

The problems became even bigger when on 25 January 1945 the men of the third platoon C Company had installed themselves in the village Schillersdorf together with white soldiers of the 103rd Infantry Division. This place was suddenly attacked by soldiers of the Waffen-SS division Nord. A chaotic retreat followed. That day, 48 prisoners were taken by the German, including 12 soldiers of third platoon, C Company, 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion. The remaining prisoners belonged to the 103rd Infantry Division. While Schillersdorf was swiftly recaptured, the captured men, and two jeeps belonging to the platoon, had already been moved.

The rest of the month it remained quiet, also because the German high command decided to abstain from further attacks. The reserves had been depleted. Operation Nordwind had not achieved the desired success, and the German troops freed from this operation could be employed at the Eastern Front.

The last months

In the month of February , it was quiet. Terrain that had previously been yielded in the retreat was recaptured, and slowly the Americans advanced, although there were no major confrontations. The 103rd Infantry Division prepared itself for breaking through the German Siegfriedline. These positions were originally designed to resist a potential French attack from the Maginotline. The positions had been left unused, until they acquired new life once the Allies landed in Normandy.

After Task Force Rhine had forced a gap in the Siegfriedline at the end of March 1945, the Americans could advance again. The 103rd Infantry Division was granted a brief respite. The men had fought hard in the previous period, and they now received rest to take care of overdue maintenance and help the local authorities with their occupational tasks.

From 20 April 1945 the 103rd Infantry Division advanced rapidly through Germany. With them went the 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion, of which the combat units were employed as anti-tank forces in various task forces. The Third Reich swiftly collapsed from both sides , and the Americans raced to the East and South. The 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion was swept along in this race and when the troops of the 103rd Infantry Division took Innsbruck, in Austria, they were there. Troops of the 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion also went along when in May 1945 a taskforce of this division was sent to the South through the Brennerpass. The intention was to unite the Allied forces in the west with the Allied forces in the South. In this manner, Nazi-Germany would be surrounded from the east, south, and west. At the moment that the American Seventh Army and the American Fifth Army met each other, the soldiers of the 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion were present.

On May 8, 1945 the war in Europe was over and the 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion was employed as part of the occupational forces in Austria. The men finally had time to take care of much-needed maintenance, which they had been unable to do in the past couple of weeks. The men and their vehicles had been pushed to the limited during the advances. The Germans had not been given any time to reorganize. At last, the war was over!

Since the battle in Europe had finished, fewer troops were needed for the combat units. Men from the unit were transferred to other units or ended up in other functions. What remained of the battalion finally returned to America, and on January 31, 1946 the unit was disbanded.

A soldier of the 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion poses with a round. Source: U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center.

After the war

During its existence, the tank destroyer battalion had shown that black Americans could fight just as well as white soldiers. They had provided evidence against the racist remarks of Secretary Stimson, who claimed that black soldiers were unsuitable for modern weapons. As Gordon McGinnis wrote: "There was one thing that helped and that was to prove to the war department that the Negro is good enough to handle as highly skilled a unit as the tank destroyer, and it does call for skill."[6] For the white soldiers of the 103rd Infantry Division no further evidence was needed, because the men of the 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion had shown what black American soldiers could do. Several white soldiers of the division returned to America with different thoughts about race than when they had left home.

For the black soldiers, their return to America will have been less glorious, because their deeds were not always recognized. As difficult as it might have been, they needed to adjust to the lives that they had left behind. Despite that their photographs appeared in magazines and newspapers, or that Lieutenant Charles Thomas was decorated with the Distinguished Service Cross, were not all white Americans willing to regard the black soldiers as equal. This changed only in 1948 when president Harry Truman decided to end segregation in the American army.

With that, not all problems were solved yet, because the struggle for equal rights and recognition endured. During the Second World War, no black American had received the Medal of Honor. Long after the war, in 1992, would Charles Thomas receive the Medal of Honor posthumously.

Notes

- Gordon McGinnis Papers, Tells Of Experiences With Tank Destroyers In France, The Ohio State News, 3 March 1945.

- Stuart Omer Landry, The Cult Of Equality, 1945, 225.

- Gordon McGinnis Papers, Tells Of Experiences With Tank Destroyers In France, The Ohio State News, 3 March 1945.

- Gordon McGinnis Papers, Tells Of Experiences With Tank Destroyers In France, The Ohio State News, 3 March 1945.

- Gordon McGinnis Papers, Tells Of Experiences With Tank Destroyers In France, The Ohio State News, 3 March 1945.

- Gordon McGinnis Papers, Tells Of Experiences With Tank Destroyers In France, The Ohio State News, 3 March 1945.

Definitielijst

- Ardennes Offensive

- Battle of the Bulge, “Von Rundstedt offensive“ or “die Wacht am Rhein“. Final large German offensive in the west from December 1944 through January 1945.

- Blitzkrieg

- The meaning of this word is “Lightning War”. Short and fast campaign. As opposed to a trench war the Blitzkrieg is very quick and agile. Air force and ground forces work closely together. First used against the Germans (September 1939 in Poland.

- cannon

- Also known as gun. Often used to indicate different types of artillery.

- Destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Medal of Honor

- United States of America’s highest military honour. Awarded for awarded for personal acts of valor above and beyond the call of duty.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- shelling

- Indication for shooting targets with grenades. Both from artillery and armoured artillery.

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

Information

- Article by:

- Samuel de Korte

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related books

Sources

- KORTE, S. DE, The 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion, Pen and Sword, Barnsley, 2022.

- LANDRY, S.O., The Cult Of Equality, Pelican Publishing Company, New Orleans, 1945.

- Gordon McGinnis Papers, AR784, 1, 5, Special Collections, The University of Texas at Arlington Libraries, Tells Of Experiences With Tank Destroyers In France, The Ohio State News, 3 maart 1945, Gordon McGinnis.