Introduction

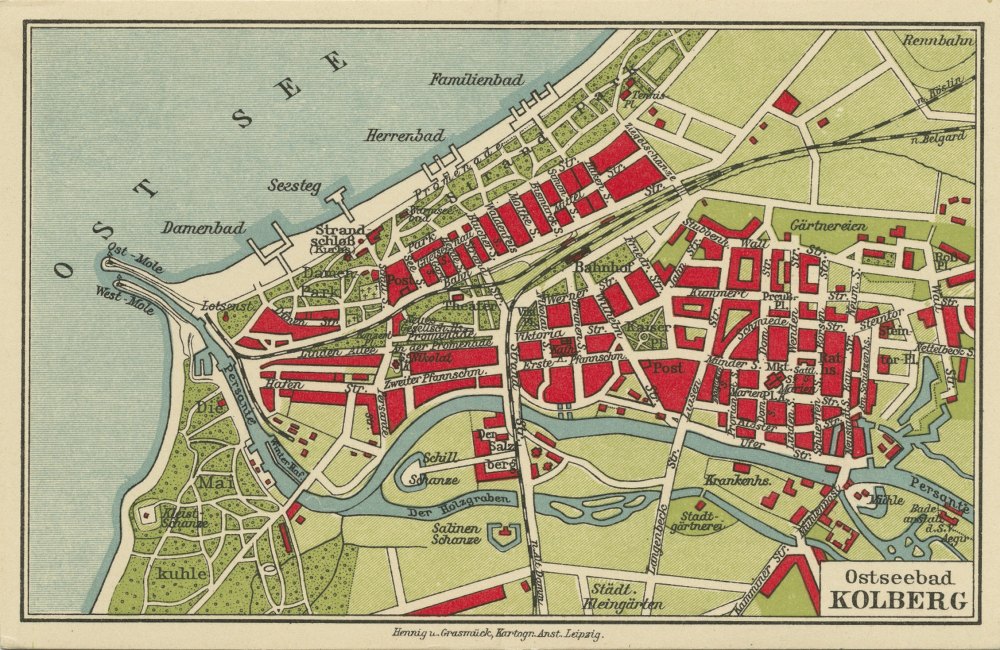

Between March 4 and 18, 1945 Kolberg (today Kołobrzeg in Poland) was under siege by troops of the Red Army and the Polish People’s Army. Since 1807, the former German bathing resort on the Baltic coast had seen no violence of war. At that time, the siege by troops of Napoleon was terminated after the signing of an armistice between France and Prussia. The propaganda movie Kolberg, which premiered in January 1945, about this siege was intended to encourage the Germans to hold out this time as well. In this it failed but until March 17, almost the entire civilian population was evacuated by sea from the city with fishing boats, merchant men and navy vessels. The majority of the military defenders of Kolberg also managed to escape by sea.

The following article is an abridged version of the book Hitler's Last Chance by the same author about Hitler’s last propaganda movie and the rise and fall of a German city. The book can be ordered in the webshop of Pen & Sword publishers.

Definitielijst

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

Previous history

The history of Kolberg on the Baltic Sea starts around the year 1000 as a west-Slavic settlement in the historic region of Pomerania along the river Persante.[1] As a result of the settling of German colonists in the late Middle Ages, a gradual Germanization took place. The city expanded with a predominant German population a few miles closer to the Baltic Sea and was granted city rights in 1255. The circular town was reinforced by moats and an earthen embankment. Kolberg developed into an important center of salt mining, trade and fishery. During the Thirty-Year War (1618-1648), the city was occupied by troops of Ferdinand II, the catholic emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. After a five-month siege, his troops surrendered to the Swedish on February 28, 1631. Shortages of food and a total lack of any chance of relief had made continuation of the fighting senseless. Swedish troops marched into town and would remain there until 1653.

In 1648, the Peace of Westphalia terminated the Thirty-Year War in the Holy Roman Empire. Lower Pomerania, including Kolberg, became part of the Duchy of Brandenburg-Prussia. Under Brandenburg rule, Kolberg was turned into a military fortress. From 1701 onwards, the city was part of the Kingdom of Prussia. Shortly after the beginning of the Seven-Year War in 1756, Kolberg would be put to the test. During this conflict, the fortified city would be under Russian siege three times, the first of which started on October 3, 1758. Due to a shortage of ammunition and the fear that Kolberg would be relieved, the Russians lifted the siege on October 28 and withdrew. It took until the summer of 1760 before they returned to lay siege to the city again. The Russians intended to attack Kolberg from both land and sea and capture it. Thanks to an attack from outside the city, led by the Prussian general Paul von Werner, the Russians fled on September 19, followed by the Swedish fleet a few days later.

The Russians didn't give up and laid siege to the city for the third time from August to December 1761. While the fortress was under enemy fire again from November 14, the German commander Heinrich Sigismund von der Heyde had the last bread distributed among his soldiers on December 15. Due to ice cold winter weather, their morale had dropped to a dismal low. Continuing the fight on an empty stomach and an exhausted spirit was useless and capitulation followed one day later. Russian control over the city wouldn't last long however. After the demise of the Czarina Elizabeth on December 25, 1761, she was succeeded by her nephew Peter III. The new czar was favorably inclined towards the Prussians and made peace on April 24, 1762. Russia returned the captured territory, including Kolberg, to Prussia.

Siege of Kolberg in 1761. Painting by the German-Russian artist Alexander von Kotzebue Source: Wikimedia Commons/Public domain

After a period of peace, lasting a little over 40 years, Kolbergians would have to endure a siege again which lasted from March to July 2, 1807. This time, the city was besieged by troops of French emperor Napoleon. The siege was laid after Napoleon’s triumphant entry in Berlin on October 27, 1806. The Prussian kingdom collapsed like a house of cards when various Prussian fortified cities surrendered without a fight. Led by the Prussian commander of the fortress August Neidhart von Gneisenau and civilian leader Joachim von Nettelbeck, Kolberg held out. In contrast to what was claimed in Prussian recorded history, the siege didn't end because of a Prussian victory. The defenders of the fortress may have held out until the end but it was the armistice between Prussia and France which ended hostilities.

In the 19th century Kolberg, as part of the German Empire would evolve into a popular bathing resort and spa. From a small fortified town, it had turned into a mundane spa around 1900. During the First World War Kolberg, situated far away from the front, was in use as a hospital town. From February 12 to July 2 1919, it was the seat of the headquarters of the Oberste Heeresleitung or high command of the army. Army commander Paul von Hindenburg took residence in a hotel which would be named after him after his departure. In the period between the two world wars, Adolf Hitler and his NSDAP won many followers in Kolberg. During the national election in 1933, the NSDAP won 9,842 (50.2 %) votes out of the valid 19,607 votes.[2]

Postcard from 1905. The beach castle of Kolberg. In the foreground basket seats on the beach Source: Brück & Sohn Kunstverlag Meißen

Although Jewish inhabitants had played an important role in the development of the city into a successful spa but like anywhere else in Nazi-Germany, Jews had to deal with anti-Semitism. From July 1935, Jewish bathing guests were refused. In May 1939, after all the bullying, discriminating measures and violence, only 83 Jews remained in Kolberg. In February 1940, the majority of them, along with a total of 1,200 Jews from Stettin and other municipalities in Pomerania, were deported to Lublin by train under the guise of ‘resettlement’ outside the German empire. Most of them perished in a ghetto or were murdered in extermination camp Belzec.[3] Whereas Jewish inhabitants were being deported, during the war large numbers of foreign civilians were taken to Kolberg to perform (forced) labor in agriculture and the industry. In 1944, Kolberg housed a total of 11,362 foreign workers, 3,941 of them Ostarbeiter or forced laborers from areas in Central and Eastern Europe occupied by the Germans.[4] In many cases, these laborers were treated badly by their German bosses.

Definitielijst

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

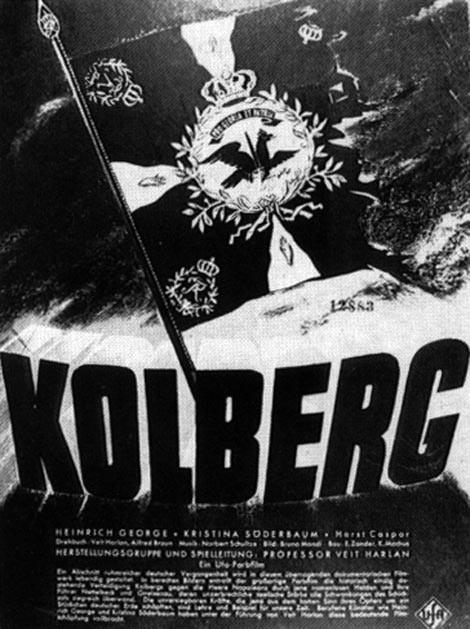

The propaganda movie

On June 1, 1943, Nazi minister of propaganda Joseph Goebbels ordered movie maker Veit Harlan to make a movie, entitled Kolberg which was to convey the same message as his speech about Total War of February 1943: mobilization of the German people and to hold out until the last man. The persistence of military and civilians alike in fortress Kolberg during the siege by the French was to serve as an example for the German movie goer. Goebbels ordered Harlan ‘to show that a united population in the Heimat and at the front can conquer any opponent’.[5] Earlier on, Harlan had been responsible for having directed the anti-Semitic propaganda movie Jud Süß of 1940. After Die Goldene Stadt (1942) and Immensee (1943), Kolberg was the third color movie directed by him. For this movie, the director had a star studded cast at his disposal consisting of Heinrich George (Joachim von Nettelbeck), Horst Caspar (fortress commander August Neidhart von Gneisenau) and Paul Wegener (Colonel Lucadou, the hated predecessor of Von Gneisenau). The fictitious Maria was played by Harlan’s wife, pretty, blond-haired Kristina Söderbaum who had played a role in the movies mentioned earlier.

The Berlin Sportpalast during Goebbels’ speech about Total War Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J05235 / Schwahn / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Kolberg was produced by the German movie corporation UFA, subordinate to the Ministry of Propaganda. Recording began on October 22, 1943. Not only did Harlan have a top cast at his disposal, regarding means of production, he didn't want for anything either. Whereas German society was entirely geared to war production and the inherent frugality, Harlan had anything at his disposal he deemed necessary for the making of his movie. In a decree of July 4, 1943, Goebbels had granted him a production budget of 4 million RM. The movie would go way over budget though, according to some calculations up to 8.5 million; although a historian published a detailed calculation, showing the cost to reach 7.6 million.[6]

Apart from a gigantic budget, Goebbels gave Harlan a free hand to ‘withdraw soldiers in any number desired from their service or training’. Moreover, Goebbels had assured him that ’whenever necessary all departments of the Wehrmacht, the Party and the State’ would be at his disposal because ‘this movie is to serve our mental waging of the war’.[7] No less than 187,000 soldiers would have been deployed as figurants, soldiers of Napoleon for example. In the movie, some mass scenes are included of the attack on Kolberg by Napoleon’s troops though but far less extras would have been needed for that. The excessive number was nothing more than propaganda and the number of 5,000, mentioned by a camera operator is far more plausible. A large part of the extras came from the Torpedoschule of the Kriegsmarine located in Kolberg. Apart from Kolberg, open air recordings were also made in Treptow, some 19 miles to the west and a little further inland. In addition, Harlan had part of the old city rebuilt in Groß-Glienicke near Berlin, in order to ‘shell and burn the buildings with Napoleon’s guns’.[8]

In August 1944, recording was finished. Filming had taken longer than intended because the movie would actually have been shown in cinemas in December 1943. Ten months of recording had yielded 90 hours of movie. Many months passed before the movie was ready and had been shortened to a playing time of 111 minutes. When in late November (according to Goebbels December 1), Harlan had shown the first version to the minister, Goebbels was far from satisfied about the result. He thought for instance, Harlan had put too much emphasis on the suffering of civilians in war time. The continuous killing and being killed would only be nerve racking to the viewer.

The movie had to be edited ‘radically’ to have it ready on time for the premiere on January 30. Obviously, the minister had lost his faith in Harlan’ s capability to complete the editing successfully and therefore he left completion of the movie to Harlan’s colleague, Wolfgang Liebeneiner who completed the editing on January 3, 1945.

Kolberg premiered in Berlin. In addition, Goebbels had the movie dropped by airplane over the German fortress La Rochelle on the French Atlantic coast so it could be shown to the men there. The movie certainly didn't become a blockbuster. Due to the shortage of cellulose nitrate, only 50 copies of the movie could be made. Whether all copies arrived at their destination is an open question regarding the chaos and destruction caused by bombings logistics also had to deal with. Apart from 13 cinemas in Berlin, within the German Empire Kolberg would have been shown in Breslau, Königsberg, Danzig, Neisse, Munich, Vienna and Hamburg. American media historian David Culbert estimates that only a few thousand Germans saw the movie during the war.[9] Compared to Harlan’s previous blockbusters, this of course was a huge deception. Kolberg wasn't only the most expensive but also the least watched movie made in Germany until then.

Definitielijst

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- mobilization

- To make an army ready for war, actually the transition from a state of peace to a state of war. The Dutch army was mobilized on the 29 August 1939.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Silence before the storm

A paradise, that is how Tina Georgi described Kolberg in the spring of 1944.[10] You could sleep well in the bathing resort because there were no air raids. Injured military recuperated in Kolberg in the sunshine. The orchestra of the spa played merry music for the people relaxing on the terraces, apparently oblivious of the fact that the Red Army was approaching fast. At the end of the year, it had almost reached Königsberg in East-Prussia and the distance between Kolberg and the front was a mere 248 miles.

The mood in the spa changed around August 1944. The usual hustle and bustle was no more. The municipal theater had closed its doors and no more concerts took place. Actors and musicians were called up this summer to work on the construction of the Ostwall or the Pommernwall a little closer. These defensive lines were to protect the German provinces in the east against a Soviet invasion. Directed by Gauleiter Franz Schwede-Coburg, in his capacity of Reichsverteidigungskommissar, civilians were called up to help dig tank moats and trenches and create field fortifications. They were transported to the front line along the river Weichsel by train or ship. Along with prisoners-of-war, East-European forced laborers, members of the Hitler Jugend, employees of the Reichsarbeitsdienst and the Organisation Todt they had to toil for days in the blistering sun.

On January 25, 1945, when roads were passable again thanks to the freezing cold and lakes and waterways frozen over, the Red Army launched its Weichsel-Oder offensive. The attack was preceded by a bombardment of the German lines lasting three hours, including the use of the notorious Katusha rocket launchers, better known as the Stalin organ after the organ like shape of the launching tubes. The Wehrmacht was no match for the enemy’s superiority of 1.6 million men and thousands of tanks and other war equipment. In less than a month, the front line shifted 311 miles in westerly direction. The Germans were driven out of a large part of postwar Poland and the distance between the front and Berlin had shrunk to less than 62 miles. From January onwards, large numbers of civilians left their home towns in East-Prussia, fleeing before the approaching Red Army. Escape by train was all but impossible. In ice-cold winter conditions, they made their way along snowy rural roads with sledges and carts filled with domestic goods and drawn by starving horses. Their destinations were the Baltic ports in the Danziger Bend from where they hoped to be evacuated by ship.

Refugees from eastern Prussia and German military on the run to the west Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1976-072-09 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Fear of the enemy was intense. Messages about plundering, raping and murdering Soviet soldiers couldn't be missed in German papers and news reels. Whereas women, children and elderly men fled before the Red Army, from October 1944 onwards all men between 16 and 60, not yet called up for military service, were enlisted in the Deutsche Volkssturm. Poorly trained and hardly armed, these aged men and fledgling youth of this civil militia were to defend their villages and cities against the Red Army on German territory. They weren’t up to their task and in particular during the fighting in East-Prussia and Pomerania, many would die in battle against the better equipped and more experienced Soviet military and their T-34 tanks and other hardware.

Definitielijst

- Gauleiter

- Leader and representative of the NSDAP of a Gau.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- rocket

- A projectile propelled by a rearward facing series of explosions.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Operation Hannibal and the Soviet advance

In the last week of January, just one third of East-Prussia was still in German hands. The Red Army had cut off the overland escape route and refugees from East-Prussia could only reach the more westerly German ports via the frozen Weichselhaf, a beach lake separated from the Danziger Bend by the Weichsel embankment. Engineers of the Wehrmacht had laid out some sort of four lane highway across the ice, bordered by trunks of fir trees stuck in the ice. Over half a million fugitives had taken this route across the ice, many of them subjected to fire from revengeful Soviet fighter pilots. After having crossed the Weichselhaf, they could be evacuated via the port of Pillau or on foot via the Weichsel embankment to Danzig and Gotenhafen.

Evacuation via the Baltic Sea was undertaken by the Kriegsmarine under the codename Hannibal. In his capacity as Seetransportchef Ostsee, Konteradmiral Conrad Engelhardt supervised this operation. In the summer of 1944, some half a million people had been evacuated from the Kurland peninsula and the Baltic states. Navy vessels as well as merchant men and even submarines were deployed just like large passenger liners which had been stripped of all luxuries like ballrooms and luxurious cabins in order to accomodate as many refugees as possible. One of those vessels was the KdF passenger liner Wilhelm Gustloff, in use since 1938 which met a gruesome fate on January 30, 1945. Carrying thousands of refugees, military and crewmembers, she was torpedoed by a Soviet submarine on her way from Gotenhafen to Kiel. Only 1,239 out of the more than 10,000 people aboard survived the disaster.

Vessels carrying German evacuees in the Baltic in 1945 Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1972-092-05 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Hundreds of thousands of civilians from Königsberg and elsewhere as well as injured military were evacuated from the ports of Pillau and Gotenhafen in January and February. Due to the poorly organized and far too late evacuation, many refugees on their way to a port would be overtaken by the Red Army. Whereas the fortresses Königsberg and Pillau held out, the Red Army made a circumventing movement with the ports of Danzig, Gotenhafen and Kolberg further west as its new targets. While the 1st White-Russian Front of Marshall Georgy K. Zhukov prepared itself at the end of January for an attack across the Oder, the last natural barrier between them and Berlin, it was covered on its right flank by the 2nd White-Russian Front of Marshall Constantin K. Rokossovski

In Pomerania and before Berlin, the Soviet troops had to be stopped by Heeresgruppe Weichsel, far less equipped and numerically weaker, which was commanded by militarily inexperienced SS leader Heinrich Himmler. A German counteroffensive on the Eastern Front in mid-February didn't help either because Hitler, despite urging by his chief of staff General Heinz Guderian, refused to bring up additional troops as he wanted to deploy them in for example Hungary. With this offensive, Nazi-Germany couldn't have influenced the outcome of the war in any way but it might have stabilized the front a little.

It became clear to Stalin that the capture of Berlin was possible, provided he would also capture the Baltic region. Soviet troops could just as well have ignored Lower-Pomerania and strike straight towards Berlin but Stalin was afraid the region could become a springboard for the Germans to attack the flanks of his troops. As to the Germans, Lower-Pomerania was an important link to 2. Armee that was fighting in west Prussia and an escape route for the civilian population.

While Soviet troops in the interior were advancing with unheard of speed, along the coast they faced a much tougher German resistance. Danzig and Gotenhafen in west Prussia would hold out until the end of March. At the beginning of that month, the 2nd White-Russian Front had reached the coast in a circumventing movement a little east from Köslin, a mere 25 miles from Kolberg. The overland route towards the German troops in Danzig and Gotenhafen had been severed as a result. On March 4, the traffic junction at Stargard, 19 miles east of Stettin, had fallen into Soviet hands. While German troops were pulling back to Stettin, Zhukov’s troops reached the coast west of Kolberg. Many villages in Lower-Pomerania, including the ports of Rügenwalde and Stolpmünde east of Kolberg, surrendered without a fight during the advance of the Red Army. The defenders of Kolberg wouldn't let that happen, just like in 1807. Whereas on March 10, almost the entire Lower-Pomerania had been captured by the Red Army from the German 3. Armee, Kolberg held out.

Definitielijst

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Fester Platz Kolberg

From the end of January until the beginning of March 1945, some 250,000 German refugees from the east would be accommodated in Kolberg, cared for, treated medically and passed on to other locations.[11] Until the siege of the city by the enemy however, refugees continued to arrive, from Pillau and Danzig for example from where many could not get away before all overland escape routes were cut off. Kolberg had suffered no more violence of war since 1807. Fortifications had been torn down, overgrown by shrubs or had become a tourist attraction. The declaration of the city to Fester Platz or fortified city had more symbolic than military value. For the first time on March 8, 1944, Hitler had designated 29 cities near the Eastern Front accordingly, meaning they had to hold out as a fortress, although there were no traditional fortifications at all or no longer in use. The intention was that these Feste Plätze would draw enemy troops like a magnet, tying them down and slowing their advance. In reality, the defenders with their insufficient means were being sacrificed in a senseless battle against an enemy whose advance could only be temporarily delayed by these local resistance nests.

As early as November 1944, the Generalkommando in Stettin had set up a defense plan for Kolberg, whereby three defensive belts were designated: the outer belt at 7.5 miles from the city, the center at 3 and the inner belt on the edge of the city. Where the soldiers to man these belts had to come from was anybody’s guess. Just like in 1807, use should be made of inundated areas. In early February 1945, civilians, foreign laborers and prisoners-of-war were to be deployed to erect fortifications on the edge of town but the rainy weather and the high level of ground water made construction difficult. Three bridges crossing the Persante, one of them a railway bridge, were rigged with explosives by engineers so they could be blown before the enemy could cross them.

Apart from the fortifications around Kolberg leaving much to be desired just like in 1807, there was another similarity with the past. At the time of the war against Napoleon, when fortress commander Lucadou was replaced, now another replacement had to be found for his 20th-century colleague Generalmajor Paul Hermann, 53 years of age and a veteran of the First World War. Suffering from sciatica and a broken lower arm from a fall on the ice, the general was in fact no longer fit for military service. He still had been able to arrange for Flak being deployed in the city and he had supervised the construction of fortifications but after being struck with the flu, his role was over. Oberst Gerhard Troschel of the engineers took over as temporary commander until on March 1, 50-year-old front officer Fritz Fullriede arrived to take command.

Fullriede didn't arrive in Kolberg with the same fighting spirit attributed to Von Gneisenau in the movie Kolberg. As early as September 2, 1944, the colonel had concluded in his diary that the eastern front was lost. He criticized the orders of his superiors and rejected the fact that young boys were deployed at the front as cannon fodder.[12] Hitler did not have to expect blind obedience from Fullriede. Cadaver discipline and the senseless sacrifice of human life were not the cup of tea of this sincere and free thinking new fortress commander. Arriving at his new post, he immediately ordered to terminate construction of the fortification as he found them senseless. There were not enough soldiers to man them and a modern, mechanized army wouldn't let it itself be delayed by means that were obsolete since the time of Napoleon.

Due to a lack of men, Fullriede ignored the plan to create three defensive belts. He would focus primarily on holding the area on the coast around the port and the mouth of the Persante in order to enable all inhabitants to be evacuated by sea and subsequently enable his men to withdraw via this route. All troops at his disposal were split in three units which had to defend their own part of the line around the city.

Kampfabschnitt West was responsible for the western line, including the Maikuhle, a park on the coast, and the beach west of the Persante. Mitte was the backbone of the defense and defended the southern edge of the city west of the Persante. Ost protected the eastern line east of the Persante up to the coast near the Waldenfelsschanze, a fortification that was no longer in use.

Kampfabschnitt West consisted mainly of two battalions of the Volkssturm, in total some 700 men. The units had been established in November and December and were commanded by 58-year-old Marine-SA Standartenführer Erhard Pfeiffer of the navy department of the brownshirts. Actually, the unit was only fit for guard duties. As often was the case for members of the Volkssturm, they were poorly armed, for instance with old shotguns with only one round and sports and hunting rifles. They sorely lacked machineguns and they were short of ammunition.

The armament of Kampfabschnitt Mitte wasn't much better. The group, consisting mainly of navy personnel, only had old Italian rifles at their disposal for which insufficient ammunition was available. Later, they would exchange these weapons for carbines. In addition they possessed hand grenades and 50 Panzerfäuste, a single-use anti-tank weapon. Commander of the group was 46-year-old Korvettenkapitän Waldemar Prien of Torpedoschule III situated in Kolberg. The nucleus of the Kriegsmarine-Alarmeinheit, established by him, consisted of pupils and staff of the torpedo school.

A member of the Volksturm training with a Panzerfaust. In Kolberg as well, men of this civilian militia were equipped with this weapon Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J31391 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Kampfabschnitt Ost was made up of the remnants of a training regiment of 3. Panzerarmee, commanded by 50-year-old Oberst Fritz Woller. Spread across the lines, a random selection of specialists was deployed consisting of railway workers, engineers, communication troops and a technical unit which was responsible for keeping open the radiotelegraph connection in which they miraculously succeeded until the end of the battle. Early March troops, cut off from their unit also arrived in Kolberg. Among them, French volunteers of the 33. Waffen-SS-Grenadier-Division Charlemagne, whose units had been cut to pieces during the fighting around Belgard and Köslin, some 15 miles inland from Kolberg.[13]

All told, Fullriede had between three and five thousand men at his disposal.[14] Apart from a shortage of men, light weapons and ammunition, there was also a lack of heavy weapons. For example, there were only eight damaged tanks available, abandoned by fighting troops.[15] In the report, submitted to the army leadership after the battle, the presence of eight light 10.5cm field mortars and 15 Flak of various calibers was mentioned. On March 6 and 7, 100 tons of various sorts of ammunition was delivered by sea.[16] In addition on March 5, an armored train was brought to Kolberg which after a few days was blown up near the main railway station by its crew due to a lack of efficiency in order to prevent it from falling into enemy hands.[17]

Definitielijst

- cannon

- Also known as gun. Often used to indicate different types of artillery.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- Flak

- Flieger-/Flugabwehrkanone. German anti-aircraft guns.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

Surrounded by the Red Army

The army advancing on Kolberg was one to be very worried about. The first wave of attack consisted of various units of the Red Army, belonging to the 1st and 2nd White-Russian Front. These included the 272nd Soviet Infantry Division (March 6 to 9) and the 45th Soviet Tank Brigade (March 4 to 7). The Persante was the dividing line between the two Fronts. In total, the besiegers would have had 1,200 guns at their disposal including Stalin organs and grenade launchers. The Red Army was probably supported by Germans of the Nationalkomitee Freies Deutschland, consisting of German prisoners-of-war who had defected to the enemy. The rumor that Germans were involved in the fighting was based on the fact that radio traffic in German was picked up from Soviet tanks.[18]

From March 7 onwards, a large part of the attack would be taken over by the 1st Polish Army, created in the Soviet Union and commanded by General Stanislaw Poplawski, part of the Polish People’s Army and belonging to the 1st White-Russian Front. Among the Polish units involved were the 6th (March 6/7), the 3rd (from March 9) and the 4th Infantry Division (from March 12). The Polish commander of the troops fighting near Kolberg was Brigade general Marek Karakoz. He had between 28,000 and 29,000 men at his disposal. He was ordered to capture Kolberg fast after which the 1st Polish Army could advance westwards in order to take over the coastal defense at the mouth of the river Oder and to provide cover to the flanks of Rokossovski’s 2nd White-Russian Front.

Leaving the capture of the town for the most part to men of the 1st Polish Army probably was a gesture from Stalin to the Poles in order to appease them. He desperately wished to keep Poland within his sphere of influence after the war. The dictator could easily afford to leave the capture of a less important city like Kolberg to the Poles. Communication between the Poles and the Russians, who continued to be involved in the bombing of the city, wasn't ideal though and this was probably one of the reasons why it would take until March 18 before the city was finally captured. By leaving Kolberg to the Poles, the Red Army could also concentrate on continuing its advance on Berlin.

Just like Napoleon hadn't reckoned with tenacious resistance in Kolberg in 1807, neither had the Soviet and Polish leadership in 1945. They thought to be able to overrun the little coastal town easily due to their supremacy. This proved disappointing because led by experienced commander Fullriede, the Germans would offer fierce resistance. Not because they all still believed in a German victory but to buy enough time to take the inhabitants and themselves to safety. This evacuation was far from easy because the number of citizens, some 35,000 in peace time, had more than doubled because of the arrival of refugees. Many had entrenched themselves in their horse carts or in cellars because all houses were already occupied.

In the evening of March 3 the last hospital train left Kolberg for Stettin via Treptow. Final destination of the train, packed with doctors, the injured and refugees was Berlin. A little later that night, a passenger train departed, destination Bad Kleinen in Mecklenburg. In the early morning of March 4, the last train with refugees still managed to escape unimpeded. A goods train, packed with refugees leaving a little later was intercepted by the Red Army.

On March 4 at 04:00, a state of siege was declared in Kolberg. This meant that full authority lay in the hands of the fortress commander. Those committing plunder or sabotage were sentenced to summary execution. Males not yet in military service and not in exceptional positions, were to report to the Schill barracks immediately where they would be placed in a military unit. Those trying to evade this faced summary execution as well. There also was the fear of unrest in the city, caused by resident foreign laborers. This fear mainly arose from racial prejudice because like German civilians in town, foreign laborers as well were trying to survive in a city that was being shelled heavily.

In addition to the railway connection, on March 4 drinking water was also cut off after the Russians had captured the water works. Some inhabitants had been smart enough to collect water in barrels ahead of time, sustaining them for a few days. Others melted snow or obtained water from the Persante. Due to enemy fire, this was very dangerous and in a later stage of the battle no longer justified. From March 5 onwards, there was no electric power either. Candles from the Dom were used to illuminate homes and shelters. Many inhabitants though left their homes because it wasn't safe there due to the shelling and moreover cold because of the shattered windows. They hid in shelters or cellars, wondering what to do next.

If the Soviets had hoped to capture Kolberg without a shot being fired, they were disappointed right on the first day of the battle. For example in the Altstadt, the original West-Slavic settlement, German forward posts managed to stop the enemy advance. After having been subjected to heavy fire for three days, the German defenders would be defeated as late as March 7. During the first days of the siege, the deployment of German warplanes – a rarity in those days – enemy tanks could be prevented from entering the city. Kolberg may have been shelled from various positions, including those east from the Maikuhle, but there was no fixed plan. The station and the railway to Belgard were being shelled by Soviet aircraft, causing the first civil victims. .[19] According to Fullriede’s report, 22 trains were ready in the station for departure but they could not get away any more.[20]

During the first phase of the siege the beleaguered city could still be supplied with food, and ammunition by vessels from Swinemünde and Stettin, thanks to the connection by sea. From the first day of the siege on, the harbor was subjected to fire although during those first days not so heavy as later on. During those days, chaos in the harbor was complete because people wanted to flee in their masses and the flow of refugees wasn't coordinated properly yet. Numerous people were trampled by horses which had broken lose and were in panic from the rumbling of guns and other noises of war.

It was a lucky break for anyone wanting to flee that there were many vessels at anchor in the harbor due to stormy weather during the previous days. In particular during the nights, under cover of darkness, vessels set sail carrying refugees. Usually the vessels assembled at the anchorages off the coast of Kolberg, sailing in convoy from there to the more westerly ports. The most important destinations were Swinemünde, Stralsund and Sassnitz on the island of Rügen. During their voyage, the vessels had to remain close to shore as deeper waters were mined.

From March 7 on, escape from the town was only possible by sea. Due to a lack of result, attempts to clear the passage along the beach to Gribow was prohibited by higher authorities. Prior to March 5, some civilians could have escaped by aircraft, taking off from Bodenhagen airfield east of Kolberg, although Luftwaffe pilots weren’t actually allowed to take refugees aboard. On March 5, the airfield could no longer be defended and had to be ceded to the enemy but not before part of the facilities had been blown by the personnel.[21]Employees of the airfield retreated to the city where they were deployed in the defense.

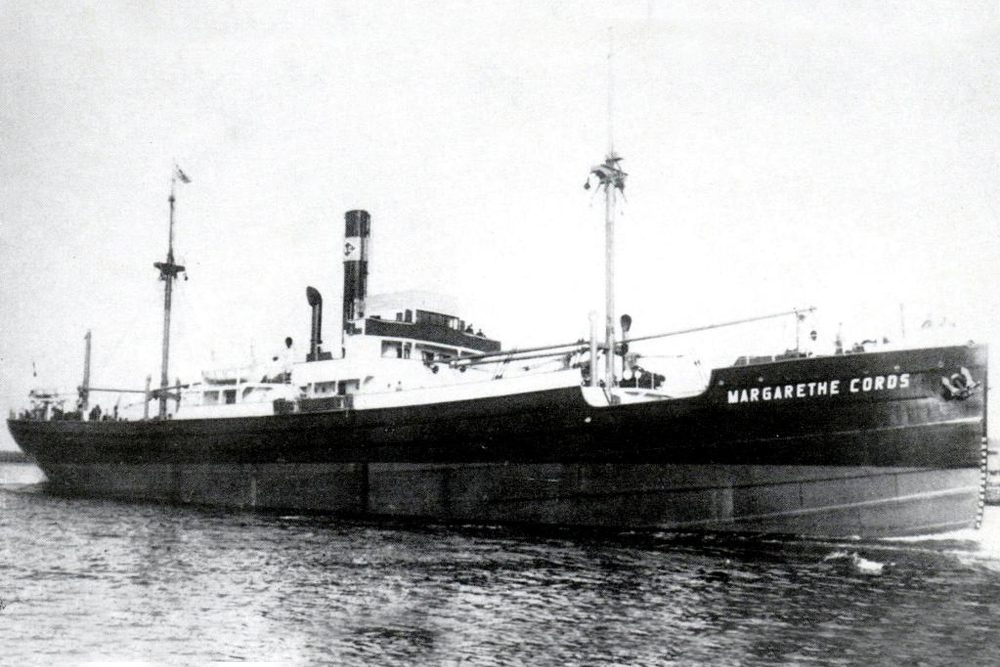

It was partly owed to the crews of the various vessels that generally speaking, the evacuation progressed smoothly. Fregattenkapitän Hans Kolbe was in charge of this operation, first from the U-Jäger 119 and from March 12 from the destroyer Z. 43.[22] A motley collection of vessels was made available for this: large and small, civil and military. Merchantmen and the Kolberg fishing fleet took part in the evacuation as well. In addition, the Kriegsmarine made a considerable contribution. For example, Siebelfähre were used to transfer as many people as possible to larger navy vessels on the anchorage. These vessels, developed by Friedrich Siebel were provisional landing craft of the Wehrmacht which would have been deployed in Operation Seelöwe, the invasion of Great-Britain. They were some sort of ferries or pontoons propelled by aero engines. Furthermore, minesweepers and Flugsicherungsboote or rescue vessels of the Luftwaffe were being deployed.

A Siebelfähre as deployed during the evacuation of Kolberg. Picture was taken in Yugoslavia in 1943 Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-005-0015-36 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Plagued by high seas, transfer from smaller vessels to larger ones wasn't only difficult for the evacuees but it required a high degree of seamanship from the crews as well. Once aboard, deprivations for the evacuees weren’t over yet. Conditions in the holds and cabins of the overcrowded vessels, usually lacking sufficient sanitary facilities were harsh. Most of those aboard weren’t used to sailing on rough seas so many suffered from seasickness.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Jäger

- Also called fighter plane. Fighter planes can be used for air defence (armed with guns and/or carrying guided missiles) or for tactical purposes (armed with nuclear or conventional bombs or rockets). The aircraft used for tactical purposes are also called fighter- bombers because they are bombers with the speed and manoeuvrability of a fighter. Tactical fighters, equipped with photographic equipment are also used as reconnaissance plane.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- shelling

- Indication for shooting targets with grenades. Both from artillery and armoured artillery.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

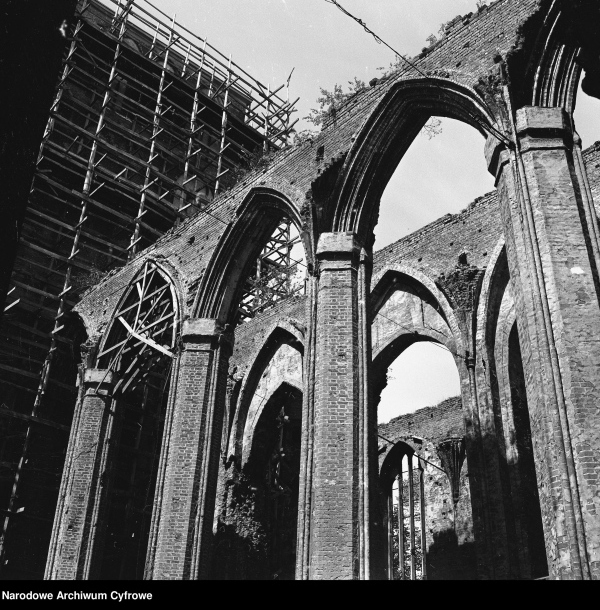

Urban battles

After the fighting had been raging in villages and settlements near Kolberg during those first days, on March 8 enemy troops approached the suburbs of the town. In the previous night, the ring around the city was closed. During the siege, the inhabitants watched how their city was gradually pounded to rubble. In the end, the enemy had over 20 artillery batteries at his disposal, shelling the city merciless.[23] The major targets were the harbor, the railway station and the front line. Especially the shelling by the Stalin organs left a deep impression. Someone described ‘the screaming and howling’ as ‘ominous’. ‘Now and then, it sounded like an unusual thunderstorm was unleashed over the city’ according to this witness.[24] More and more buildings caught fire, including the Dom and the municipal theatre on March 8. The next day, the church tower collapsed, robbing the city of its prominent recognition point. On various locations, carts abandoned by refugees were on fire with the corpses of dead horses next to them.

One of the locations where heavy fighting raged was near the railway station. A train can be seen departing at the last moment Source: Drzewieniecki Collections / Digital Commons Buffalo State

Many refugees in the harbor had found shelter in Fort Münde, the customs office and nearby houses. Here they found some protection against the variable wintry conditions while waiting for a ship to evacuate them. The beaches in the vicinity of the harbor were strewn with suitcases and other baggage, abandoned by the refugees. Along the front lay the corpses of dead German military. The Germans usually had no time or opportunity to bury their dead. Civilians buried their dead in court yards and gardens if possible.

Civil life in town suffered heavily from the relentless artillery fire. According to Fullriede there was ‘panic among the civilian population’ and also a ‘high mortality rate among infants owing to a shortage of milk and drinking water’. According to him, it happened frequently that mothers killed their own children or people committed suicide.[25] At the same time, the fortress commander praised the courageous conduct of many women ‘who, while helping to put out fires or recovering the injured, endangering their own lives, set an example to a large part of the male population’.[26]

On March 11, reinforcements arrived on the anchorage off Kolberg. Both destroyers Z 34 and Z 43 as well as torpedo boat T 33 dropped anchor here. Both destroyers were equipped with for example some 150mm guns and the torpedo boat likewise with four. .[27] The navy vessels were able to defend themselves with their anti-aircraft weapons against Soviet planes that attacked immediately. The artillery aboard the vessels was used to plaster enemy targets ashore. This meant a great relief for the defenders who had only five active 105mm guns at their disposal.[28] After having played an important role in stopping the enemy in the east, Z 34 left for Swinemünde the next day, carrying 800 refugees and 120 injured. She was still in open water when the Americans bombed Swinemünde.[29]

On March 11 and 12, enemy troops had managed to penetrate the line in the south and southeast of town after bloody fighting. They suffered huge losses from the heavy German fire from the naval vessels as well. On March 13, the defenders had almost completely pulled back to within the borders of the city, the last belt of defense. That day, Polish and Soviet troops attacked from all directions. The fighting was heavy in for instance the Maikuhle in the west and at the Waldenfelsschanze in the east. Troops of the Volkssturm were unable to hold their positions in the west and lost them to the enemy. Although an increasing number of soldiers deserted, in general there was no question of surrender yet. ‘We shall fight as long as there is one bullet left and we are still alive’, the Berliner Morgenpost quoted Heinz Bertling who was mistaken for the fortress commander.[30]

Polish military during the fighting in town Drzewieniecki Source: Collections / Digital Commons Buffalo State

The enemy placed great value on capturing both the Maikuhle and the Waldenfelsschanze. After all, the first location offered direct entry into the harbor and from the second location, the harbor was within firing range. On March 14, the enemy managed to penetrate deep into the Maikuhle. Fullriede placed the entire harbor area under command of Korvettenkapitän Waldemar Prien. On his orders, navy personnel established a new defensive line which was from that moment on almost continuously under fire. In the harbor, the German had blown the light tower on Fort Münde because it was a far too easy aiming point for the Soviet artillery.[31]

The Waldenfelsschanze couldn't be held either. From March 16 onwards, Stalin organs plastered the city from there. German artillery deployed in town was disabled for the most part. German infantry men could do little against the enemy. On March 15, reinforcements arriving by sea could make no difference as not everyone could be put ashore. On March 14, Polish military leadership had demanded the surrender of the Germans twice. Fullriede had taken notice of the first demand and he had ignored the second.[32] Calls for capitulation by the Soviets were being ignored as well. An unanswered ultimatum for the Germans to capitulate on March 15 before 16:00 was the last failed call to surrender.[33] What looked like German overconfidence was in fact a battle for survival. Even though the enemy had penetrated deep into the city and enemy artillery caused massive damage, thanks to the deployment of the naval guns, the harbor could be held and evacuation continued.

On March 17, evacuation of the citizens was complete. According to Fullriede’s report, since the beginning of the siege, fishing boats, merchant men and naval vessels had evacuated over 70,000 civilians. Apart from inhabitants of Kolberg and refugees from the east, this included members of unarmed civil organizations and foreigners (forced laborers and prisoners-of-war).[34] This didn’t mean the end of the evacuation from Kolberg though as the soldiers defending the town had to get away as well.

Definitielijst

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- shelling

- Indication for shooting targets with grenades. Both from artillery and armoured artillery.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Final battle and evacuation

On March 16, the enemy had penetrated into the city center. Parts not yet captured were continuously subjected to fire from the Russian artillery. The same day, the Russian 6th Rocket Brigade of the Red Army had arrived as reinforcement. Meanwhile, the defenders had an ever dwindling number of weapons at their disposal. The artillery had only rocket launchers available which were deployed on the beach. Most artillery crews had found shelter in the beach castle as they couldn't do anything elsewhere and did not want to sacrifice themselves unnecessarily. Just a few streets were still in German hands but the defenders were exhausted, physically and mentally and only continued fighting to survive. They knew that on leaving their positions, chances at escape were lost.

As early as March 16, fortress commander Fullriede had decided to evacuate his troops although he hadn't been ordered accordingly by high command. That day however, no vessels were available, postponing the transport for a day. The next day, permission to evacuate didn't materialize either. The high command of 3. Panzer Armee only reported that due to ‘overburden’ it was unable to pass on a decision. Fullriede therefore decided on his own initiative to launch the evacuation of the troops in the evening of March 17. Troops had to be taken off the eastern breakwater and from a predesignated spot on the beach. The injured had been evacuated beforehand. On the anchorage, a few ships were already waiting to pick up military.

In the early morning of March 18, Z 43 and T 33 returned to the anchorage where Z 34 was already at anchor. While the ship’s artillery delivered covering fire, Schnellboote raced to and from the eastern breakwater to transfer military to the waiting vessels. Boarding elsewhere was no longer possible as the enemy had taken up positions on the west bank of the Persante. A Siebelfähre, towed by a buoy boat, a small motor vessel for supporting tasks in the harbor, was deployed to evacuate navy personnel from the western part of the beach. Near the marina, the vessel picked up some members of the Volkssturm who had been left behind, as well as 50 soldiers from the eastern breakwater. With some 500 men aboard, the vessel was overloaded and on her way to the anchorage she listed heavily. While she was being fired upon by enemy artillery, those aboard were transferred to other vessels.[35]

A German Schnellboot such as was deployed during the evacuaton of military from Kolberg Source: IWM / Lt. J.E. Russell, Royal Navy official photographer

On March 17, the situation of the defenders of the city had become hopeless. In the Maikuhle, the enemy had penetrated to just 30 yards from the beach. Surviving troops of the Volkssturm, which had been chopped to pieces, drew back towards the harbor. In the city, isolated German soldiers were still fighting for the railway station and other targets. Buildings in the center were set ablaze by the Germans in order to create a wall of fire to stop the enemy advance. Captured German soldiers were taken to the city hall which had been captured by Polish troops. On the beach near the castle, the Germans still held a narrow strip, 1,800 yards long and 400 wide. Here and around Fort Münde as well, the defenders had dug in, awaiting transport.

After all military had been evacuated from the designated locations, fortress commander Fullriede followed them with a few members of his staff. First he made an inspection tour along the coast in a rubber dinghy before he and his men boarded Z 43 at 06:30.[36] Whereas 2,000 or more German soldiers were being evacuated, an estimated 300 men were left behind in the ruined city. They had not been able to reach the harbor from their positions or made up the rear guard which had offered resistance to the last. Others got lost or deserted. Hidden in cellars and among rubble they awaited the arrival of Poles and Soviets who would make them prisoners-of-war.[37] Fullriede left some 600 to 800 dead warriors behind of whom 441 had been identified in 2005 and registered in the Book of Honor of the Fallen of Kolberg.[38] Counting and identifying the German military victims was laborious as many of them had been buried in individual nameless graves or in mass graves.

The number of civilian victims is even harder to determine than the number of military victims. After all, there were many unregistered refugees, evacuees and foreign forced laborers in town. Estimates vary between a few thousand up to 17,000 civilian victims.[39] After the siege, many would die anyway. Among those remaining, there were many elderly and sick people who could not cope physically with the privations in the almost entirely destroyed city.

Polish soldiers in the captured town near Fort Münde in the harbor Source: Polish National Archive/Public domain

Later on, fortress commander Fullriede would describe the battlefield as the ‘firy hell of Kolberg’ and compare it to the battles of Verdun, Douaumont and the Somme during World War One.[40] In his report of the battle of Kolberg he proudly established that his troops ‘without their own anti-tank weapons’ had disabled 28 enemy tanks. Twelve of them had been knocked out with short-range weapons, the rest by Flak and artillery. Moreover, an unknown number of enemy tanks had been knocked out by German naval artillery. Fullriede praised the ‘flexibility and the accuracy’ of his artillery but also claimed that holding out for 14 days without the support of naval artillery, ‘would undoubtedly have been impossible’

Despite Fullriede having had ‘poorly armed and hastily established fighting groups’ at his disposal, according to his report, ‘human losses’ of the enemy were ‘extremely high’. ‘According to a careful estimate’, so the report reads, ‘substantiated by declarations of prisoners, the enemy has suffered losses up to 50 %’. Finally he concludes that ‘an entirely burnt out and ruined city’ has fallen into enemy hands. ‘The Dom is a burnt out and severely damaged ruin. All bridges across the Persante and the Houtgracht have been blown. The station and the shunting yard have been ruined, the port infrastructure is unserviceable for a long time. This is the profit the enemy made at the cost of enormous sacrifices in blood but also the price that was paid to save 75,000 people for the Reich.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Flak

- Flieger-/Flugabwehrkanone. German anti-aircraft guns.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Rocket

- A projectile propelled by a rearward facing series of explosions.

German defeat

The news of the loss of Kolberg also reached Joseph Goebbels, who actively kept track of all developments at the front. Earlier on he had could have noted in his diary that the defense of Kolberg held out, on March 19, he couldn’t ignore the defeat. ‘We had to evacuate Kolberg’, he wrote. ‘The city which has defended itself with such exceptional heroic courage, couldn't be held. I shall see to it that the evacuation of Kolberg will not be mentioned in the communique of the OKW. We can’t have that now, regarding the psychological consequences for the Kolberg movie’.[41] In so doing, the propganda minister wanted to prevent at all cost that the German population would hear about the loss of the city via the daily report of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht. Even during the final stages of the battle he wanted to do anything he could to prevent the Germans from losing their faith in the final victory.

Despite the fact that he had terminated the hostilities on his own initiative and surrendered Fortress Kolberg, when he returned to Germany, Hitler awarded him the Ritterkreuz mit Eichenlaub on March 23, 1945. "His gift for organization and his personal courage have played a decisive part in the defense of Kolberg,’ an article in a news paper reported.[42] On April 20 followed his promotion to Generalmajor

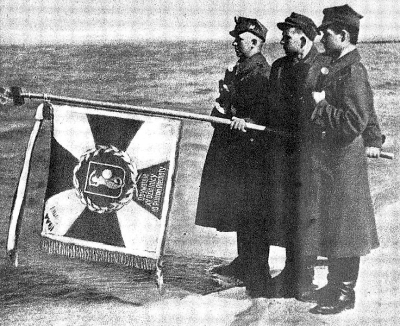

After their victory, Polish and their allies of the Red Army fired their rifles and guns into the Baltic Sea. Polish battle banners were symbolically dipped in the cold surf of the Baltic. The spontaneous festivities would have lasted for three days.[43] In comparison to the other belligerent parties, the Poles had probably paid the highest price for the capture of Kolberg. In the Book of Honor of the Fallen of Kolberg, 1,441 Polish victims are registered against 257 Soviets.[44] The latter number is probably higher actually because many soldiers of the Red Army had been buried anonymously, hence an exact number is difficult to determine. Right after the battle, a few dozen Polish and Soviet military were buried on the circular plateau of Fort Münde where the light tower once stood. During the sixties they were reburied in a military field of honor in the central grave yard.[45]

Definitielijst

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Polish take-over

Although Kolberg had remained completely undamaged during the war up to March 4, two weeks later it was one of the most heavily destroyed cities in the former eastern provinces of Germany.[46] An estimated 75 to 90% of the town was in ruins. In order to prevent an epidemic from erupting, removal of the corpses was priority no. 1 for the city council, to which authority had been transferred by the Soviets on June 1, 1945. Remaining German inhabitants and arrested looters were deployed to remove corpses from the houses and fish them out of the river. The recovered corpses were taken by horse and carriage to a park to be buried, sometimes anonymously in mass graves.

The first weeks after the take-over of the city by the Poles, from June 1, 1945 onwards known as Kołobrzeg, can be considered a period of pioneering. An unorganized immigration started by Poles settling in town, probably drawn by its location on the sea and the expected employment in the harbor. Most of them were adult males who wanted to bring in their families later on. Among them people looking for work and adventurers but also looters. Initiated by the repatriation office of the Polish government, families also settled in town after the war. At the end of 1945, 1,373 Poles lived here and 3,239 Germans. The expulsion of the latter to Germany had started after the Potsdam Conference of August 2, 1945. After the change-over from 1945 to 1946, expulsion would continue until at the end of 1946, there were probably no more Germans in the Polish town.

As late as the fifties, reconstruction of the town started in earnest, maintaining the original plan of the city as much as possible, although all streets were renamed in Polish. The harbor was made operational again and various (state) enterprises were opened. The Polish government had decided to redevelop the city into a spa and destination for tourists and recreation. Hotels were erected just like spa’s and other facilities. The Dom was partly renovated in 1958 and put to use as the Polish Museum of Arms which is now located elsewhere in the city.

TThe fall of the Iron Curtain and the Polish entry into the European Union triggered new impulses and brought hordes of tourists from the West. Germans once more enjoyed visiting the city. In the year 2000, the German-Polish relations were strengthened by the unveiling of a monumnent in the Maikuhle in memory of the Germans who had been buried in grave yards that had disappeared after the war.

Notes

- The major sources of the description of the history of Kolberg until World War One are:

- Voelker, J., Geschichte der Stadt Kolberg

- Eitner, H-J., Kolberg – Ein pruissischer Mythos 1807/1945

- kolobrzeg.de/geschichte-info/geschichte

- www.kolobrzeg.pl/historia-miasta.

- Rademacher, M., Deutsche Verwaltungsgeschichte 1871-1990.

- jüdische-gemeinden.de.

- Spoerer, M., ‘NS-Zwangarbeiter im Deutschen Reich’, Vierteljahrshefte für zeitgeschichte, nr. 49, Oldenburg, 2001.p. 674.

- Eitner, H-J., Kolberg – Ein Preußischer Mythos 1807/1945, pp. 150-151.

- Noack, F., Veit Harlan: The Life & Work of a Nazi Filmmaker, p. 222.

- Eitner, H-J., Kolberg – Ein Preußischer Mythos 1807/1945, p. 158; Kutz, J.P., ‘Veit Harlans Kolberg: Der letzte "Großfilm" der Ufa’, 2008, p. 2.

- Kutz, J.P., ‘Veit Harlans Kolberg: Der letzte "Großfilm" der Ufa’, 2008, p. 3.

- Culbert, D., ‘Kolberg: Goebbels' Wunderwaffe as Counterfactual History’, p. 136.

- Georgi, T., Mein Leben im Wechsel der Zeit, p. 168.

- Eitner, H-J., Kolberg – Ein Preußischer Mythos 1807/1945, p. 170.

- Kershaw, R., De straat: Oosterbeek-Arnhem, september 1944, pp. 44-45.

- Voelker, Johannes, Die letzten Tage von Kolberg, pp. 180-181.

- Schön, H., Pommern auf der Flucht 1945, p. 148.

- Voelker, Johannes, Die letzten Tage von Kolberg, p. 180.

- Gefechtsbericht über den Einsatz in Kolberg vom 4. - 18. März 1945, Bundesarchiv, BArch RH 84/2.

- Voelker, Johannes, Die letzten Tage von Kolberg, p. 70.

- Eitner, H-J, Kolberg: Ein Preußischer Mythos 1807/1945, p. 162; Gefechtsbericht über den Einsatz in Kolberg vom 4. - 18. März 1945, Bundesarchiv, BArch RH 84/2.

- Voelker, J., Die letzten Tage von Kolberg, p. 61.

- Gefechtsbericht über den Einsatz in Kolberg vom 4. - 18. März 1945, Bundesarchiv, BArch RH 84/2.

- Voelker, J., Die letzten Tage von Kolberg, p. 73.

- Schön, H., Pommern auf der Flucht 1945, p. 181.

- Gefechtsbericht über den Einsatz in Kolberg vom 4. - 18. März 1945, Bundesarchiv, BArch RH 84/2.

- Voelker, J., Die letzten Tage von Kolberg, p. 91.

- Gefechtsbericht über den Einsatz in Kolberg vom 4. - 18. März 1945, Bundesarchiv, BArch RH 84/2.

- Gefechtsbericht über den Einsatz in Kolberg vom 4. - 18. März 1945, Bundesarchiv, BArch RH 84/2.

- Schön, H., Pommern auf der Flucht 1945, p. 180; Detailed information about the armament of these vessels can be found on:

- Eitner, H-J., Kolberg – Ein Preußischer Mythos 1807/1945, p. 189.

- Voelker, J., Die letzten Tage von Kolberg, p. 117.

- Eitner, H-J., Kolberg – Ein Preußischer Mythos 1807/1945, p. 195.

- Voelker, J., Die letzten Tage von Kolberg, p. 125.

- Eitner, H-J., Kolberg – Ein Preußischer Mythos 1807/1945, p. 196.

- Voelker, J., Die letzten Tage von Kolberg, pp. 138-139, 148.

- Gefechtsbericht über den Einsatz in Kolberg vom 4. - 18. März 1945, Bundesarchiv, BArch RH 84/2.

- Voelker, J., Die letzten Tage von Kolberg, pp. 171-173.

- Duffy, C., Red Storm on the Reich: The Soviet March on Germany 1945, p. 233.

- Eitner, H-J., Kolberg – Ein Preußischer Mythos 1807/1945, p. 201.

- Voelker, J., Die letzten Tage von Kolberg, pp. 182-183.

- Voelker, J., Die letzten Tage von Kolberg, p. 178.

- Eitner, H-J., Kolberg – Ein Preußischer Mythos 1807/1945, p. 202.

- Goebbels, J., Dagboek 1945: 28 februari 1945-10 april 1945, p. 188.

- ‘Eichenlaub für Oberst Fullriede’, Deutsche Zeitung in den Niederlanden, 05-04-1945.

- Eitner, H-J., Kolberg – Ein Preußischer Mythos 1807/1945, p. 217.

- Voelker, J., Die letzten Tage von Kolberg, p. 199.

- Voelker, J., Die letzten Tage von Kolberg, pp. 200-201.

- Sources of the description of the post-war town:

- Suchu, J., ‘Kolberg (Kołobrzeg) an der Ostsee – Das Bild einer Küstenstadt auf wiedergewonnen Gebieten nach dem. 2. Weltkrieg’, Studia Maritima, vol. XXVII/2, 2014;

- Jancke, P., Führer durch eine untergegangene Stadt;

- miasto.kolobrzeg.eu/epoki-historyczne

- kolobrzeg.de/geschichte-info/geschichte .

Information

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 29-01-2023

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!

News

Hitler's last propaganda film premiered 79 years ago

January 30, 2024 marks the seventy-ninth anniversary of the premiere of Hitler's last propaganda film. The title of this film directed by German director Veit Harlan is Kolberg. The subject is the 1807 siege of the German city of the same name on the Baltic coast by Napoleon's troops. The Prussian army, supported by a civilian militia, had then held out for months against the besiegers. The film story was intended to inspire and encourage Germans in early 1945 to keep up the fight. The film and the rise and fall of the German town of Kolberg are the subjects of Kevin Prenger's latest book Hitler’s Last Chance: Kolberg. The following is an excerpt from his book. It is about the making-of of the film.