Introduction

Movie director Veit Harlan was a celebrity within he Nazi cinema. He was known for his melodramatic motion pictures but today he is better known for having directed the anti-Semitic propaganda movie Jud Süß. It was also this director who was selected by Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels to make a motion picture that was to convey the same message as his speech about Total War on February 18, 1943. On June 1, 1943, he sent the director a written order to make this Großfilm of movie corporation UFA which was to be named Kolberg. The text of this article about Veit Harlan was taken from the book Kolberg (about Hitler’s last propaganda movie and the rise and fall of a German city) by the same author.

Definitielijst

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

From stage to movie set

Veit Harlan was born in 1899, one of six children of a playwright.[1] After the gymnasium, he was trained as a silversmith and afterwards he was admitted to drama school, the highly regarded Max Reinhardt Seminar in Vienna. In 1916, aged 17, he reported for voluntary service in the German Imperial Army. The defeat must have been a deception for him, just like for many nationalistic Germans of his generation. From 1919, he found a new vocation on stage. He acted in the Preußisches Staatstheater for 11 years. During his stage career, he met his first wife, German-Jewish actress and cabaret singer Dora Gerson. The marriage did not last long though, from 1922 to 1924. On February 14, 1943 the woman, along with her second husband and two young children, would be murdered in Auschwitz.

On April 20, 1933, he had a role in the play Schlageter, performed in the theater mentioned before in the presence of Adolf Hitler on occasion of the latter’s birthday. The drama, written by Nazi playwright Hanns Jost (as of 1935 president of the Reichsschrifttumskammer) was about a German veteran form the First World War, committing acts of sabotage in the Rhineland after the war against the French occupier and executed by them for that reason. The play, based on a true story was the characteristic martyr tragedy the Nazis loved so much: self-sacrifice for the Fatherland as the highest honor.

In addition to his stage career, Harlan also acted in movies between 1927 to 1935. In that year he directed his first movie but it was Der Herscher from 1937 he made his breakthrough with. The main role was played by popular Emil Jannings who played a self-made business man whose wife suddenly dies. Hilde Körber, since 1929 Harlan’s second wife, played Jannings’ daughter. The actress would also appear in other movies by her husband, including Der Große König from 1942 about Friedrich der Große.

Definitielijst

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Rhineland

- German-speaking demilitarized area on the right bank of the Rhine which was occupied by Adolf Hitler in 1936 after World War 1.

Successful career in the Third Reich

Owing to his successes, Harlan gained a place in the high society of the Third Reich. He was on friendly terms with Goebbels, they frequented each other’s homes. On March 14, in Harlan’s home on 28 Tannenbergallee in Berlin, Goebbels sat with his ears glued to the radio, listening to the report of Hitler’s triumphant entry into Vienna.[2] Using a special pass, Harlan could always gain entry through the back door into the Ministry of Propaganda on Wilhelmsplatz in the German capital, a privilege enjoyed by only the most important movie makers.[3] Goebbels’ mistress, Czech actress and singer Lida Baarová, was a friend of Harlan’s second wife.

After a marriage of nine years, Harlan divorced Körber with whom he had three children. He married again in 1939, this time with a colleague from the movie set, Swedish-born Kristina Söderbaum, 13 years his junior. She appeared exclusively in a number of his movies, among them Jud Süß in which she played Dorothea Sturm, the woman raped by Joseph Süß Oppenheimer. She also appeared in Der Große König, Die Goldene Stadt (1942) and Immensee (1943) The attractive blond often played the naïve, lovable, childish woman, an example of the obedient, innocent Aryan young lady. As she died in the water in many roles, she earned the nickname Reichswasserleiche (water corpse). In the motion picture Opfergang (1944), she is seen horse riding in the surf, dressed in a white bathing suit (she later admitted she had been scared to death). With her girlish looks, her natural beauty and blond curls, she strongly appealed to the (male) movie goer. Almost all productions by her husband in which she appeared, were successful.

In a gesture of appreciation by the Nazi government, on March 4, 1943, Harlan was bestowed the title of professor on occasion of the 25th birthday of UFA. He was addressed by Ludwig Klitzsch, from 1927 to 1942 chief executive of UFA and later head of the financial department of the Reichskulturkammer. He praised the years of ‘excellent artistic craftsmanship’ of the director. ‘In your best movies and in particular during the war, you have grabbed the German population by the belt, strengthening its moral resistance.[4]

Definitielijst

- moral

- The will of the troops/civilians to keep fighting.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

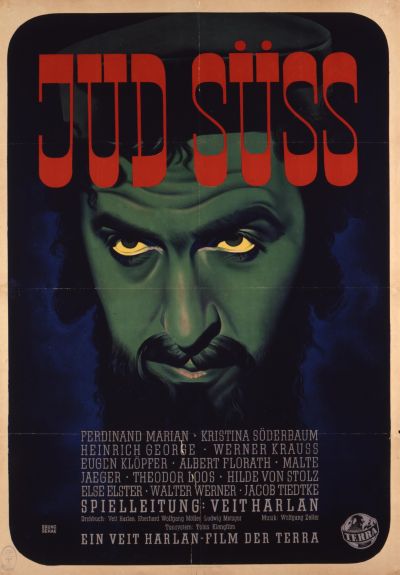

The maker of Jud Süß

Harlan was the director of the best known anti-Semitic propaganda movie Jud Süß from 1940. In this movie, produced by Terra Filmkunst, the Jewish banker Joseph Süß Oppenheimer is appointed by 18th century Herzog Karl Alexander von Württemberg as financial advisor. After taxes have been raised by Oppenheimer and the duchy is flooded by Jews after the ban on settlement had been lifted, a revolution erupts which ultimately leads to the expulsion of the Jews and the execution of the main character.

In addition to being corrupt and power mad, the Jewish character is also portrayed as a rapist. In one of the scenes he abuses a German woman, played by actress Kristina Söderbaum, Harlan’s wife. Goebbels was very pleased about the director’s description of Jews being unreliable and subversive. After having studied the script, on December 15, 1939, he entered the following in his diary: ‘The movie Jud Süß has been edited perfectly by Harlan. This will be the anti-Semitic movie’.[5] The minister was right, because the movie became a big success. In 1943, 20.3 million people had seen the movie. This number only applies to Germany because it was released in occupied countries as well, including the Netherlands where it became a flop however.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- revolution

- Usually sudden and violent reversal of existing (political) the political set-up and situations.

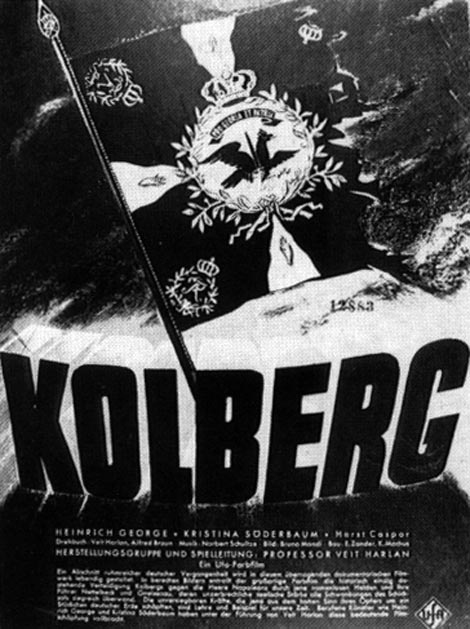

Production of Kolberg

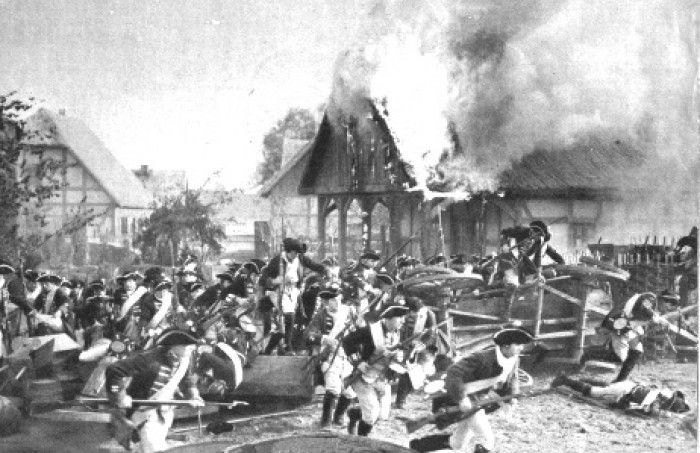

In the written order to make Kolberg, which Harlan received from Goebbels, the latter indicated that the intention of the movie was to ‘show that a population, united in the Heimat and at the front, defeats any opponent’.[6] The subject of the movie was to be the German city on the Baltic coast with the same name that was besieged in 1807 by troops of Napoleon. At the time, the Prussian army had held out for months supported by a civil militia against the besiegers. Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels wanted the Germans in 1945 to emulate the example of the Kolbergians in 1807: hold until the last bullet and defeat the enemy.

With Der Große König Harlan had already demonstrated he could handle a historic epos with an actual analogy. The movie is about how Friedrich der Große held out after the defeat in the Battle of Kunnersdorf, was victorious during the Battle of Torgau in 1760, saving Prussia from the brink of disaster against all expectations. One of the leading characters, a corporal whose actions decide the battle to the advantage of Prussia, dies in the arms of his leader, Friedrich der Große. When viewers replaced the 18th-century king with the dictator of the 20th century, then they had understood the message of the movie well: unconditional loyalty to and an unshakable belief in the Führer should lead to a big turnaround of the situation in the war in 1942, even though during the past winter when the advance into the Soviet Union had ground to a halt and imminent victory seemed impossible.

Whereas Der Große König was still in black and white, Kolberg was to be produced in Agfa color, developed in 1936 and the equivalent of the legendary American Technicolor. After Die Goldene Stadt and Immensee, Kolberg was the third color movie directed by Harlan. According to Goebbels, Harlan was eager to start work on Kolberg although the latter denied it himself. The director was wildly enthusiastic about the task, if we are to believe the diary entries of the minister.[7] Enthusiastic or not, Harlan started working on the script. Goebbels kept track of progress meticulously and criticized the contents if and when he did not like it.

Recording the movie was begun on October 22,1943. Not only did Harlan have a top cast at his disposal, including Heinrich George, Paul Wegener and Gustav Diessl; as to means of production he didn't want for anything either. Whereas German society was geared entirely to war production and the inherent frugality, Harlan could have anything at his disposal he deemed necessary for making his movie. By decree of July 4, 1943, Goebbels had granted him a production budget of 4 million RM. The movie would go way over; according to some estimates up to 8.5 million although a historian published a detailed calculation in 2011 amounting to 7.6 million.[8]

Those who participated in the movie were spared the misery at the front or the dangerous work in the war industry but the days of shooting were anything but a holiday. To camera operator Gerhard Huttula, participation in the movie was the ‘most embarrassing experience of my entire professional career’. In his view, it was ‘outright torture’ and ‘this man Harlan was a fanatic, really. He didn't care about his coworkers at all.[9] Allegedly, five figurants would have lost their lives during the shooting.

Definitielijst

- Propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

A major flop

In August 1944, recording was completed. It had taken longer than intended as actually the movie was to have been shown in cinemas as early as December 1943. Ten months of shooting had yielded 90 hours of movie. Several months passed before it was ready and shortened to a playing time of 111 minutes. When at the end of November, (according to Goebbels on December 1) Harlan had shown the first version to the minister, the latter was far from pleased with the result. The movie was too pacifistic for his liking and contained elements which would only frighten the movie goer. ‘Cut-cut, cut-cut, in this way some 2 million RM was edited out and disposed of’, Harlan said who apparently wasn't overly happy to delete valuable scenes ordered by his boss. In his words, work continued ‘day and night’ and ‘Goebbels watched the movie time and time again.’[10]

The trial run on December 23, in the presence of actor Heinrich George and movie maker Wolfgang Liebeneiner, triggered another reaction from Goebbels: ‘Instead of improving the movie, Harlan has made it worse,’ he furiously wrote in his diary. The movie had to be edited ‘radically’ to finish the movie on time before its premiere on January 30. Obviously, the minister had lost faith in Harlan’s ability to finish the cutting-and-pasting process properly because he left completion of the movie to Liebeneiner who made the last corrections on January 3, 1945.[11]

Compared to Harlan’s previous blockbusters, Kolberg was a major flop. At the moment the movie premiered in Berlin on January 30, 1945 and on the German U-boat base at La Rochelle in France, the Ardennes offensive had failed, the Red Army had advanced up to 43 miles from the German capital and cities were subjected to heavy bombing raids. As a result of the state of war, distribution of the movie faltered. In any case, German citizens did have something else on their minds other than to go and see a movie. Therefore, Kolberg wasn't only the most expensive but also the least watched movie produced in Germany up to then.

Harlan survived the war himself unscathed but after this house on Tannenbergallee in Berlin had become uninhabitable on December 12, 1944 due to bomb damage[12], the cinematographer and his family moved to Amtitz Castle in Gruben. This was the former residence of Prince Ferdinand zu Schoenaich-Carolath who had been imprisoned on charges of having listened to foreign radio stations.[13]

Definitielijst

- Ardennes offensive

- Battle of the Bulge, “Von Rundstedt offensive“ or “die Wacht am Rhein“. Final large German offensive in the west from December 1944 through January 1945.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- U-boat

- The German name for a submarine. German U-Boats (Submarines) played a very important role during the course of warfare until May 1943. Many cargo and passenger ships were torpedoed and sunk by these assassins of the sea.

Post war trials

Veit Harlan’s post war career bore much resemblance to that of his colleague movie maker Leni Riefenstahl. He also aimed at full rehabilitation and international recognition of his artistic work. His Nazi past would continue to haunt him for the rest of his life though. Right after the war, in May 1945, he wrote a ‘will’ explaining his position within Nazism. His defense was, he wouldn't have had another choice than making propaganda movies. He would repeat this excuse successfully until his death. His conviction of his innocence was confirmed three times by a court.

In December 1947, the deNazification tribunal in Hamburg placed him in the category Entlastete, meaning acquittal. This ruling caused commotion for instance among German victims of Nazi persecution and in the British Control Commission. A high ranking British official within the occupation authorities, considered the ruling ‘monstrous’.[14] A revision of the case, in which Harlan would probably be placed in the category Mitläufer (follower) was thwarted by a penal case which was opened against the movie maker by the public prosecutor in Hamburg in 1948, which led to a trial before the court in the same city. The simultaneous holding of two trials was considered unworkable so the deNazification tribunal ended without a definitive verdict.

During a trial in 1949, opened by two organizations of Nazi victims and others, Harlan was charged with crimes against humanity. By making Jud Süß he would have contributed to anti-Semitism which ultimately led to the Holocaust. The prosecution demanded two years imprisonment and a fine of DM 150,000, but the defendant was acquitted,[15] because ‘the connection between his movie and the crimes of the Nazis could not be established’. In 1950, the case was reopened because the high court in Cologne had rejected the earlier verdict because ‘the court hadn't sufficiently considered the subjective side of the case’. Once again, Harlan pleaded his innocence. He called Goebbels ‘the greatest demon of the past thousand years’ and claimed he couldn’t have rejected the order to make Jud Süß because this would have endangered his life and that of his family as well.[16] This time he was acquitted as well.[17]

A salient fact: the judge responsible for the last two acquittals wasn’t exactly unblemished himself. This Walter Tyrolf had been a member of the Nazi Party and at the time of the Third Reich, as judge of the Sondergericht, in Hamburg, he had frequently passed death sentences for petty thievery and ‘racial disgrace’, After the war, the judge could resume his work as usual.[18]

Definitielijst

- crimes against humanity

- Term that was introduced during the Nuremburg Trials. Crimes against humanity are inhuman treatment against civilian population and persecution on the basis of race or political or religious beliefs.

- deNazification

- Post war policy of the allies in Germany to punish Nazi war criminals and to remove known Nazis from positions of power or public service.

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Nazism

- Abbreviation of national socialism.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

Under fire

Because of his acquittal, nothing stood in Harlan’s way to resume his career as a movie maker after a ban of 5 years. In 1951, his first post war movie was released, entitled Unsterbliche Geliebtein which his wife also played a major role again. Ten more movies would follow, among them Anders als Du und Ich (§ 175) from 1957. What seemed like a movie advocating emancipation of homosexuals (intercourse between men was prohibited up to 1994, pursuant to paragraph 175 of the penal code of the Federal German Republic) was, according to a prominent German movie encyclopedia an ‘infamous, Fascist and amateurishly staged movie’.[19]

This homophobe movie, as well as all other post war productions directed by Harlan, could count on much criticism mainly from Social democrat and Jewish circles. In some cases his movies were banned by cinemas and received negative reviews in the (leftist) press. At premieres and public showings, protests erupted frequently, from students for example.[20] The director kept defending himself continuously, in particular against criticism of his Nazi past. In 1951 for instance, he reacted with a rebuttal against a critical article in the Hamburger Abendblatt. He denied ever having been an anti-Semite and indicated that in all trials, it had been established that he ‘with exceptional courage’ had stood up against Goebbels by siding with Jews and political opponents. ‘That I, an outspoken philosemite’[21] ‘was given the order to stage Jud Süß is a tragic case’, he wrote. ‘I have proven to the courts that I fought this order for so long that, in the presence of many witnesses, Goebbels yelled at me: "I can crush you."’[22]

Although much can be said against Harlan’ s defense that he couldn't have rejected making Jud Süß (he could have reported sick or have fled to a neutral country), his argument he had stood up for victims of the Nazis, isn’t just made up. For instance, during the recording of Kolberg he tried to protect his light technician Fritz Kühne against entering service in the Volkssturm for which he had been called up. If the man was to go to the front, he would have had to leave his Jewish wife Loni behind, seriously endangering her life. Their fear was so great, the couple committed suicide in their home in Potsdam on November 5, 1944. They left behind a note to Harlan and his wife, indicating that ‘all their goodness and love had been in vain’. The Kühnes expressed their deepest gratitude: ‘God will reward you for all you have done for us’. The couple’s funeral was attended by Kristina Söderbaum and her colleague Kurt Meisel. Harlan himself was too busy with Kolberg so he let it pass.[23]

In 1954 Harlan, still under fire, had enough. During a press conference in Zürich, Switzerland, he burned one of the last two remaining copies of Jud Süß and declared to be ‘deeply ashamed’ having been involved in this movie.[24] This did not prevent his work from not being appreciated by all. In 1963 for instance, performance of a play written by him and entitled Traumspiel was thwarted by local authorities. ‘This is pure slander’, was his reaction, ‘I have never been a Nazi’. He charged former Nazis with putting the blame on him. ‘It was the tragedy of my life that I was a gifted director with the intention to make good movies,’ he lamented. ‘I just had to take charge of the movie Jud Süß. I think it is unbelievable that it still haunts me.’[25]

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

Demise and aftermath

April 13, 1964, Veit Harlan died from cancer and a cardiac problem at the age of 64 in a hospital on Capri.[26] In the last years of his life, he spent much of his leisure time in his villa on the Italian island. He left his wife Kristina, with whom he had celebrated his 25th marriage anniversary three days before his death, with two children from their marriage and three children from his previous marriage to Hilde Körber. Maria and Susanne, his daughters from the latter marriage, used their mother’s Christian name during their stage careers in order to avoid association with their father’s blemished character. Their brother Thomas criticized the Nazi past of his dad. He compared Jud Süß to an instrument of murder.[27]

Kristina Söderbaum appeared in over 10 motion pictures between 1951 and 1993, including those of her husband. Her last appearance was in the badly judged, but English spoken German movie Night train to Venice, with Hugh Grant in which she played an elderly lady. She was still popular in post war Germany. She supported her husband in his defense against the accusations against him because of his Nazi career. In her words, Jud Süß had destroyed their lives.[28] A remark she made in 1991, following an interview with British documentary maker and historian Laurence Rees, says much about the way she looked back on the Nazi past. ‘To be honest,’ she told Reese, ‘since the end of the war, I tried to read about all the horrible things Hitler did. But it is very difficult, you know because he had the most beautiful blue eyes. And moreover, he always was extremely kind to me.’[29] Apparently, she was just as naive in real life as she was in the movie roles she played. She died on February 12, 2001 at the age of 88.

Notes

- Biographical data of Veit Harlan taken from:

- Moeller, F., Harlan - Im Schatten von Jud Süß (documentary), 2008;

- Noack, F., Veit Harlan: The Life & Work of a Nazi Filmmaker The University Press of Kentucky, Lexington in Kentucky, 2016;

- Jung, G., Veit Harlan - Ein Filmemacher im Faschismus, Diplomica Verlag GmbH, Hamburg, 2009

- Reinke, K.U. (red.), 30. Januar 1945 – Uraufführung in La Rochelle und Berlin, Atlas Filmhefte, deel 61.

- Reuth, R.G., Goebbels: Eine Biographie, Piper Verlag, München, 2012, p. 482.

- Moeller, F., Harlan - Im Schatten von Jud Süß (documentary), 2008.

- Reinke, K.U. (red.), 30. Januar 1945 – Uraufführung in La Rochelle und Berlin, Atlas Filmhefte, deel 61.

- Goebbels, J., The Goebbels Diaries, 1939-1941, H. Hamilton, Londen, 1982, p. 67.

- Eitner, H-J., Kolberg – Ein Preußischer Mythos 1807/1945, Quintessenz Verlags-GmbH, Berlijn, 1999, pp. 150-151.

- Chambers II, J.W. & Colbert, D., World War II, Film, and History, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1996 p. 70.

- Noack, F., Veit Harlan: The Life & Work of a Nazi Filmmaker, p. 222.

- Giesen, R., Nazi Propaganda Films: A History and Filmography, Mcfarland & Co, Jefferson, North Carolina, 2008, p. 171-172.

- Giesen, R. & Hobsch, M., Hitlerjunge Quex, Jud Süss und Kolberg, Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf, Berlijn, 2005, p. 455.

- Culbert, D., ‘Kolberg: Goebbels' Wunderwaffe as Counterfactual History’, Historical Reflections, deel 35, nr. 2, 2009, p. 132.

- Noack, F., Veit Harlan: The Life & Work of a Nazi Filmmaker, p. 228.

- Ibid., p. 257.

- Tegel, S., Jew Süß: Life, Legend, Fiction, Film, Continuum, 2011, Londen, p. 205.

- ‘Veit Harlan vrijgesproken’, Het Parool, 25-04-1949.

- ‘Veit Harlan opnieuw voor de balie’, Trouw, 01-04-1950.

- ‘Veit Harlan opnieuw vrijgesproken’, Trouw, 02-05-1950.

- Marek, M., ‘Fassbinders Vorbild’, Welt am Sontag, 11-04-2004, on: Welt.de.

- Heyne-Filmlexikon, via: Wikipedia.de.

- ‘Groeiende actie tegen nazifilmregisseur Veit Harlan’, De Waarheid, 01-02-1952; ‘Film van Veit Harlan in ons land?’, De Waarheid, 09-04-1953; ‘Harlan (regisseur 'Jud Süß') staat op come-back in Aken’, Het Vrije Volk, 08-06-1962.

- A philosemite is someone who is favorably inclined towards the Jewish people or the Jewish faith, the opposite of an anti-Semite

- Collem, S. van, ‘De Metamorphose van Veit Harlan’, Nieuw Israelietisch weekblad, 01-06-1951.

- Noack, F., Veit Harlan: The Life & Work of a Nazi Filmmaker, pp. 226-227.

- ‘Veit Harlan verbrandt "Jud Süß"’, Het nieuwsblad voor Sumatra, 21-04-1954.

- ’"Dit is je reinste laster..." - Veit Harlan zegt nooit nazi te zijn geweest’, Friese koerier, 23-09-1963.

- ‘Veit Harlan overleden’, De Volkskrant, 14-04-1964.

- Moeller, F., Harlan - Im Schatten von Jud Süß (documentary), 2008.

- Ibid.

- Rees, L., Their Darkest Hour, Ebury Press, Londen, 2007, p. 244.

Definitielijst

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

Information

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!