Prologue

In the night of December 14 to 15, 1941, the Dutch submarine Hr. Ms. O 16, sailing on the surface in the South-Chinese Sea, hit a Japanese mine. The vessel broke in two and sank within a minute. All crew members below deck went down with her. The six crew members on the bridge ended up in the water. Only one of them, Quartermaster Cor de Wolf managed to reach land after a swim of over 30 hours; he survived the accident and reported about it later.

Definitielijst

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

Previous history

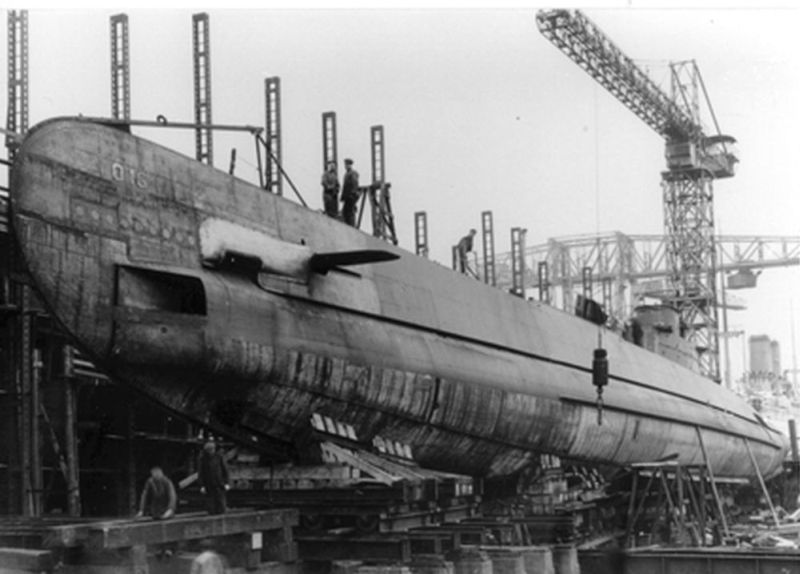

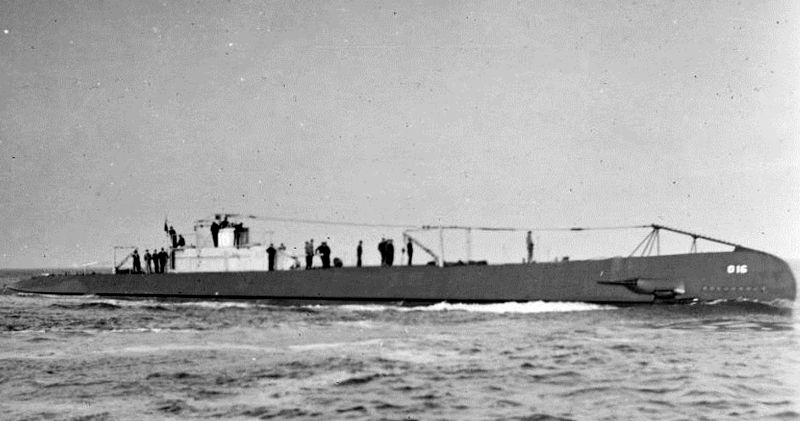

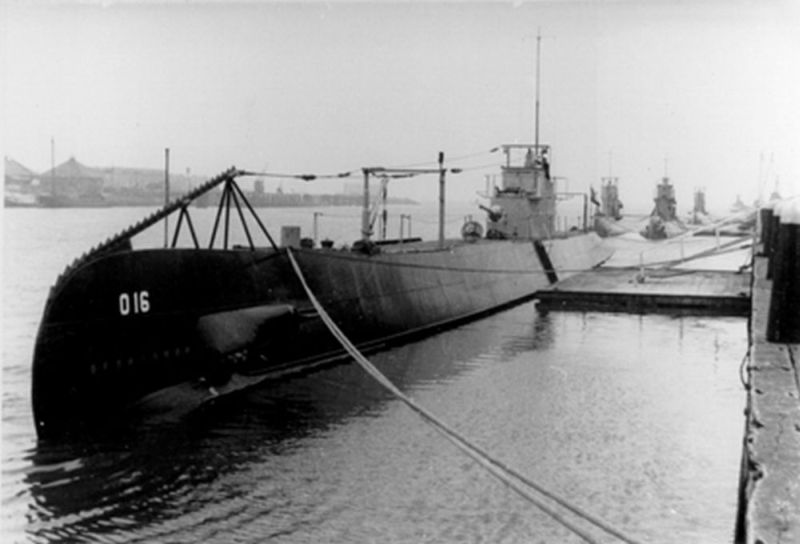

Hr. Ms. O 16 was commissioned on October 26, 1936. At that time, the Dutch submarine was one of the most modern in the world. The vessel, over 250 feet in length and displacing almost 1,200 ton submerged was constructed entirely of type 52 hardened steel and half of the habitual rivets had been replaced by far stronger welding joints. The submarine was armed with eight torpedo tubes, an 88mm deck gun and two 40mm Vickers machineguns. In addition, Hr. Ms. O 16 was the first Dutch submarine equipped with a noise detector of the Atlas Werke in Bremen and two Nedinsco periscopes, developed by a sister company in Venlo of the German Carl Zeiss company. Moreover, she was the first submarine in the world equipped with an experimental snorkel. This Dutch invention enabled a submarine to sail submerged on its diesel engines while sucking in air through a device fitted on a long extendable tube. All this made Hr. Ms. O 16 a fearsome offensive weapon.

On December 1, 1941 Hr. Ms. O 16 and the submarine Hr. Ms. K XVII were posted to the Dienst Onderzeeboten -DOZ 1- in the Dutch East-Indies. From that day on DOZ 1 was put under British operational command of the C-i-C China, vice-Admiral Sir Geoffrey Layton. As since May 10, 1940, general mobilization had been declared in the Dutch colony, the crew of Hr. Ms. O 16 had been brought up to war strength of 42 members. Layton stationed both vessels in Singapore and send them on patrol on December 6 in the South-Chinese Sea east of mainland Malacca, today Malaysia. En route to her patrol area to the south of the southernmost point of Indo-China, Hr. Ms. O 16 spotted two Japanese destroyers. Commander Luitenant-ter-Zee 1st class A.J. Bussemaker took no action however as the Netherlands were not yet at war with Japan.

Two days later, December 8, the crew aboard Hr. Ms. O 16 learned that the Imperial Japanese Navy had attacked Pearl Harbor and that the United States as well as the Netherlands had declared war on the Land of the Rising Sun. The message of the Navy Commander in Batavia -today Djakarta- read verbatim: 'war with Japan broken out, England and the US now allies'. The mission of the Dutch vessel had now turned into a war patrol. This meant attempts had to be made to sink enemy ships in order to inflict as much damage to the Japanese as possible and to defend the so-called Malacca wall, the defensive ring around Malacca. In the night of December 11 to 12 the first opportunity presented itself when the Dutch submarine spotted a Japanese troop carrier. Due to bad vision, a result of tropical thunderstorms, Commander Bussemaker couldn't see whether the enemy vessel had been hit by one of the three torpedoes that had been launched. That same night, Hr. Ms. O 16 spotted a second Japanese vessel that could easily be pursued because it carried a stern light. Having a light on the elevated aft deck of enemy transporters would trigger the sinking of four large Japanese merchantmen.

Definitielijst

- mobilization

- To make an army ready for war, actually the transition from a state of peace to a state of war. The Dutch army was mobilized on the 29 August 1939.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

First - and last - success of Hr. Ms. O 16

Unaware of being followed by an enemy submarine, the Japanese vessel sailed in the direction of the Malaccan mainland. Aboard the sub, a coast light was spotted making determining her position that much easier. The Japanese ship was heading for Patani and at night around 21:30 she dropped anchor in Sungei Patani Bay. Patani was located a little north of Kota Baru close to the border of Siam. Hr. Ms. O 16 surfaced and propelled by her W. Schmitt electric engines she slipped into the 30 feet deep bay unnoticed thanks to the expert navigation of navigator Van Eijnsbergen. Before the war, Luitenant-ter-Zee 2nd class of the Koninklijke Marine Reserve (KMR) H.J.J. Van Eijsbergen had sailed as a mate with the Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij (KPM) and knew the waters of the East like the back of his hand. To his great joy, commander Bussemaker spotted another three Japanse transporters at anchor. After Hr. Ms. O 16 had manouvered into position she launched four torpedoes from her bow tubes in quick succession at the enemy ships.

Commander of Hr. Ms. O 16: Luitenant-ter-Zee der 1e klasse A.J. Bussemaker Source: http://Dutch Submarines

All four projectiles hit their targets and three out of the four Japanese vessels sank in the shallow water. A fifth torpedo had to be launched from her aft tubes at the fourth Japanese vessel before it met the same fate as the others. Quartermaster De Wolf wrote in his declaration later on: 'now three other transporters are spotted ahead of us. Totally unnoticed we approach on the surface in silent mode. Then the order is given to prepare the tubes for launching. Of course, everything is ready and immediately afterwards, the order 'pin out!' is given. The last safety device to prevent the torpedoes from preliminary launching is removed. Slowly, the commander steers the boat into firing position. Five torpedoes are launched in quick succession. Five heavy explosions are heard by everyone below, meaning five hits. Afterwards, we quickly leave the inlet shaped by the coast line'.

According to Japanese information released after the war, in the night of December 12 1941, four of their transport vessels were sunk by an unknown submarine in the mouth of the River Patani: the Tosan Maru of 8,666 tons, the Sakura Maru of 7,170 tons, the Asosan Maru of 8,812 tons and the Ayata Maru of 9,788 tons. Although the vessels had been heavily damaged, they could be recovered, repaired and put back into service later in the war. Having said that, the daring attack of Hr. Ms. O 16 was a great success.

For the crew of Hr. Ms. O 16, it was important to leave the shallow bay safely after the attack on the Japanese vessels. The boat sneaked out of the bay on her electric engines and afterwards, it switched to her two 8 cylinder MAN diesel engines. Sailing at 18 knots, the boat set course for open sea. After the immediate danger was over, she continued at a more economic cruising speed and in the central the success was celebrated with wine and congratulations to commander Bussemaker.

As Hr. Ms. O 16 had only one torpedo left, she set sail for Singapore to replenish ammunition and stores. By day she sailed submerged on her electric engines and by night on her diesels at high speed, charging her batteries. Along the way, another Japanese transport was spotted but her last torpedo couldn't be launched as the vessel was hidden from view by a violent rainstorm. She continued her journey uneventfully until fate struck in the night of December 14 to 15.

Definitielijst

- Siam

- Name of Thailand

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Sinking of the vessel

Quartermaster De Wolf, who had the middle watch -from 00:00 to 04:00- came on the bridge at midnight to relieve the helmsman. Shortly after this release, five other crew members were on the bridge with him: the commander, the first officer and officer of the day Luitenant-ter-Zee 2nd class C.A. Jeekel, Corporal Engineer A.F. Bos, Seaman F. Kruijdenhof from Surinam and the youngest seaman, F.X. van Tol who had turned 21 on October 18. Both seamen acted as look outs. Commander Bussemaker had come up because from 11:30 onwards, a searchlight had been spotted which appeared over the horizon time and again. At about 02:00, De Wolf was ordered to maintain course in the direction of the light. After having held his course for about 30 minutes there was a violent explosion near both deck tubes. The quartermaster on the bridge described it as follows: 'suddenly, about 02:30 a loud bang, I see how the boat near the deck tubes breaks apart, an enormous column of water descends on the bridge, followed by the warm smell of diesel. The commander and the senior officer attempt to kick the tower hatch close but to no avail. My raincoat is caught in the equipment but I manage to pull free; the boat sinks within a minute, subsequently I am in the water'.

Hr. Ms. O 16 had struck a mine northeast of the island of Tioman and due to the explosion she had broken in two and gone down very fast. The 36 crew members below deck went down with her. The six men on the bridge ended up in the lukewarm but rough waters of the South-Chinese Sea. Quartermaster De Wolf reports: 'I look around me and find nothing, I start calling and get an answer, the others are floating a little further away, I swim towards them. As I reach them we are all together except the commander. We call the commander and we get answers but he can't come to us, he was probably too far away, I haven't seen him since too. I ask whether mister Jeekel knew what it could have been. He informed me it had probably been a mine. We determine where we were and it soon turned out that when we wanted to swim to the islands, we should keep the moon to our left and a star to our right. So we swam next to each other but Seaman Van Tol could hardly make it. We had taken our clothes off already but Van Tol still wore a small jacket and couldn't get it off. I couldn't watch this so I swam back to help him and I succeeded'.

'Daylight came and a few moments later, Van Tol went down. Far away on the horizon we saw the islands; I often encouraged the men to keep swimming. At 08:00. mister Jeekel went down as well. I asked Bos and Kruijdenhof how they were but their only response was : "thirsty." Gradually we could distinguish mountain tops on the islands. Rescue might be near, an airplane flew past but didn't see us. At 09:00, Seaman Kruijdenhof went under, I remember the time exactly because my watch ran until 10:00, then it stopped. I was left with only Bos then. We kept swimming but I noticed that the current pushed me far to the east of the islands. I then swam with Bos against the current till we were in line with the islands again and then straight on. Another airplane approached, it was a Dutch aircraft but it didn't see us either. An enormous thirst plagued me when the sun went down, 17 hours already. Thereafter Bos said to me "Cor, I can't make it anymore, if you get out of this alive, say hello to my wife and two kids", then he went down into the deep'.

Definitielijst

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

Rescue of Quartermaster De Wolf

Despite De Wolf having lost the other survivors and the disappointing meeting with the two aircraft had yielded nothing, somewhere he found the strength somewhere to go on. Only a person with the endurance and determination of a wolf can put up so much physical and mental strength. He wrote about this: 'again, I continue swimming, God continuously gave me the strength to remain afloat, I was pushed away by the treacherous current all the time. I swam like a robot, I didn't think of sharks, I didn't think of anything. Suddenly I saw land. I could hardly judge my situation anymore. Finally, after having swum some 35 hours, I reached the island on Tuesday around noon. The surf flung me onto the rocks. I got a deep cut in my back from one of them. Bleeding profusely from my back and legs, I remained lying on the rocks while the surf washed over my legs. The sun burned my body fiercely; intense pain in my back and legs and an enormous thirst brought me back to reality'.

Assuming that De Wolf could tell time fairly accurately from the position of the sun and he reached the island around noon, he had been swimming for some 33 to 34 hours and during that time covered a distance of some 50 miles, an unbelievable achievement that demands the highest respect. Without knowing it, De Wolf had beached on the island of Dayang or Pulau Dayang some 31 miles south from mainland Malacca. This uninhibited island is close to the larger Pulau Aur.

De Wolf may have reached land but he wasn't out of the woods yet. His survival depended on finding water and help. He wrote about this: 'I had to get water, that was my main concern. I then started walking uphill for some five hours but to no avail, there was no water there. I fell everywhere, got up again, thistles scratching my entire body. As I didn't find any water up the hill, I decided to go down again and spend the night on the rocks. When I came down, I found a crevasse with water running out of it. I laid down to drink, then I fell into an irregular sleep, I woke up time and again. Throughout the night, something nibbled at my toes but I didn't have the energy to ward it off. Up until today, I don't know what it had been. As the sun rose, I attempted to walk around the island; it wasn't easy because of rocks everywhere, between 20 and 23 feet high. After climbing and clambering for a long time, I reached the side of the island. To my great joy I spotted a small fishing vessel. I yelled as loud as I could , the young native heard me and came sailing towards me'.

The Malaysian gave the Dutch mariner a cocoanut to quench his worst thirst and hunger a little. In addition he gave him a shirt and gestured to come with him in his boat. The Dutchman accepted this offer thankfully and was taken to another, inhibited island. In a kampong, he was given some clothing and was taken to the kepala kampong -the village eldest. De Wolf explained in bad Maleis -native Indonesian language- what had happened and he was received warmly. He was offered a hut and a plate of sago with rice and water. Next day, a Malaysian Customs official working in Singapore and who spoke English well, arrived in the village. The Dutchman asked him if he could be taken to Singapore so he could report to the submarine base. He stayed in the kampong for three days and in that time the village elders decided to take the blanda (white man) to mainland Malacca and from there to Singapore.

On Saturday December 20, 1941, De Wolf and four inhabitants of the island left at 08:00 in a boat to Malacca where they arrived in the course of the day. There they joined a group of Chinese who were on their way to Mersing, a small town on the eastern coast of Malacca, accompanied by a guide. Plodding through jungle and marshes they arrived in the vicinity of Mersing. A few Malayans who went ahead to cut a path through the jungle, encountered a man who identified himself as an Australian soldier. He belonged to Allied troops who were establishing posts on the Malaccan coast from where they could reconnoiter eventual enemy amphibious landings. The Australian took the Dutchman to his base camp while the islanders returned to their vessel. De Wolf was well received by the Australians and was given food, shoes, clothing and medical care. After interrogation he was taken to Singapore in a 'luxurious Ford V8' as he called it.

On arrival in Singapore De Wolf was admitted to the sickbay in the camp of the Dutch submarine service, The physician who examined him declared he was healthy and only needed enough water, food and rest to recuperate. The next day he was interrogated by two Dutch naval officers who later reported on the fate of Hr. Ms. O 16. Later that day, the Dutch quartermaster was taken to vice-Admiral Layton who wanted to hear firsthand what had happened to the Dutch sub under his command. The same afternoon, De Wolf departed for Batavia aboard the confiscated KPM vessel Hr. Ms. Janssens. On arrival in the capital of the Dutch East-Indies, he reported to vice-Admiral Conrad Helfrich, the commander of the Dutch Navy in the East, who promoted him to boatswain. After a few days of rest, Boatswain De Wolf was posted aboard Hr. Ms. K XI and in March 1942 he escaped to Australia with this boat. He served in the Dutch submarine service for the remainder of the war.

Definitielijst

- kampong

- Malayan word for village( in the vicinity of a city), neighbourhood, quarter, fenced off yard, living area.

Epilogue

The report of the two Dutch officers who had interrogated Quartermaster De Wolf could lead to the assumption that Hr. Ms. O 16 had entered a British minefield. In the report the remark was made that it was doubtful whether De Wolf had been swimming as long as he had indicated. Commander Bussemaker was aware of the presence of British mines south of Tioman so the report suggested that he had altered course due to an error in navigation or bad weather. That kind of mistake could blemish the excellent reputation of Commander Bussemaker and his navigation officer Van Eijnsbergen.

On December 21, 1941, all radio communication was lost with the Dutch submarine Hr. Ms. K XVII which at that moment was in the same area as Hr. Ms. O 16 had been. In order to solve the mystery surrounding the disappearance of Hr. Ms. K XVII, H.C. Besançon, the son of Commander Besançon of K XVII, to search for the lost sub. Via the Instituut voor Maritieme Historie -IMH or Institute of Naval History- he made contact with the Australian diver Michael Hatcher. who had discovered the wreck of a submarine in the South-Chinese Sea near the island of Tioman. In May 1982, Besançon Jr. and Hatcher led a diving expedition to the wreck. Based on the recovered bronze helm the unknown sub could be identified as Hr. Ms. K XVII

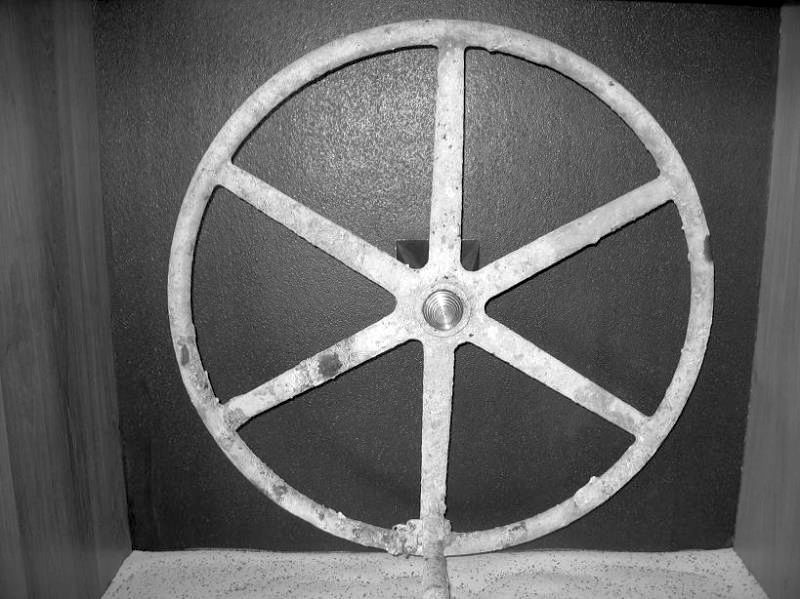

.In 1995, Swedish diver Sten Sjöstrand reported he had discovered yet another wreck of a submarine at less than 10 nautical miles from the wreck site of Hr. Ms. K XVII. Urged on by the next-of-kin of the crew members of Hr. Ms. O 16, the Koninklijke Marine organized an expedition to the newly discovered wreck in September 1996. Among the members of the expedition, apart from H.C. Besançon, H.O. and A.P. Bussemaker, sons of Commander Bussemaker and like Besançon Jr. retired Navy officers were present. The wreck, with a giant hole in the hull forward of the bridge was identified from some recognizable parts as that of Hr. Ms. O 16.

According to Japanese data released after the war, it appeared that the auxiliary minelayer Tatsumiya Maru had been ordered to lay mines to the southwest of Tioman even before the attack on Pearl Harbor. On December 6, 1941 however, the Japanese vessel had been spotted by a Dutch seaplane northeast of Tioman, causing the vessel to alter course. Before the minelayer returned to base though, she laid a defensive screen of 456 mines, 20 nautical miles from her original position and squarely across the route of both Hr. Ms. O 16 and Hr. Ms. K XVII. This exonerated the commanders and their navigation officers from any incompetence. Moreover, the position of the wreck proved that Quartermaster De Wolf, taking account of the local currents, certainly had been swimming for over 30 hours to save himself.

Cornelis de Wolf was decorated with the British Distinguished Service Medal for extraordinary bravery and ingenuity in wartime, by Royal Decree No 90 of March 7, 1947 he was decorated with the Bronzen Leeuw for extraordinary bravery and the Oorlogsherinneringskruis He retired on August 1, 1962 in the rank of opperschipper. 'The wolf of O 16' died in November 1983.

Information

- Article by:

- Peter Kimenai

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 25-03-2023

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- BEZEMER, K.W.L., Zij vochten op de zeven zeeën, Uitgeversmaatschappij W. De Haan N.V., Zeist, 1964.

- BOSSCHER, PH., M., De Koninklijke Marine in de Tweede Wereldoorlog deel 2, Uitgeverij T. Wever B.V., Franeker, 1986.

- MARK, C., Schepen van de Koninklijke Marine in W.O. II, De Alk bv, Alkmaar, 1997.

- MüNCHING, L.L. VON, Schepen van de Koninklijke Marine in de 2e wereldoorlog, De Alk bv, Alkmaar, 1978.

- POOLMAN, K., Allied Submarines of World War Two, Arms & Armour Press, London, 1990.