Introduction

The siege of Breslau (the present Polish Wroclaw) took no fewer than 80 days and was fought between the Soviet sixth army and the garrison of the ‘Festung Breslau’ [Breslau Fortress]. Eventually, the Red Army would fail to capture Breslau, but the commander of the ‘Festung’, General der Infanterie Hermann Niehoff capitulated on May 6, 1945 and handed over the city to the Soviets. The siege of Breslau is considered to be one of the bloodiest battles of World War II, with many thousands of casualties on both sides. Many compare the fighting in and around Breslau with that of Stalingrad.

Definitielijst

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

Preview

On July 25, 1944, the town of Breslau was declared a ‘Festung’ (fortress), by Adolf Hitler, who thereby gave the order to defend the city at whatever the cost. Karl Hanke, (‘Gauleiter’ of Lower Silesia since 1941) was appointed by Hitler as ‘Kampfkommandant’ (battle commander). On August 25, 1944, the construction of fortifications and field positions began in order to strengthen the Festung Breslau. Coordinations for these preparations were executed by Generalmajor der Artillerie Johannes Krause, who on September 25, 1944, was appointed the first commander of the Festung. He was supported in this by Hanke.

Franz Kutschera (left) and Adolf Hitler (right) in 1944. Source: Nacistična raznarodovalna politika v Sloveniji v letih 1941 - 1945. Maribor, 1968.

On September 15, 1944, Hanke gave a speech in the Jahrhunderthalle (Hall of the Century), in which he demanded the introduction of a ten-hour working day in order to promote the expansion of the Festung Breslau. In October 1944 Breslau was bombed for the first time. Early in January 1945, Karl Hanke was asked about the future of Breslau, to which he replied:

'Russians wil never take it. I would rather burn it to the ground.'

Definitielijst

- Gauleiter

- Leader and representative of the NSDAP of a Gau.

Preparations

Strategically Breslau had a perfect location. It was surrounded by natural canals and marches, difficult for armoured and mechanized units to pass through. These natural obstacles were reinforced by fortifications. The formation of the Festung Breslau was accelerated by the fact that the city had already been used in the past as a fortress. Fortifications from earlier times only needed to be rebuilt and modernized. Sixteen fortresses had already been built in this way in Schwoitsch (now Swoiczyce).

The cityscape also was dramatically altered. After the forced evacuation of the population of Breslau, the Wehrmacht, aided by the Volkssturm and forced labourers, began to transform the city into a fortress. Houses, squares and streets were changed into independent strongpoints. In addition, streets were barricaded lengthwise and tank barriers were created in some places. Most of the buildings around intersections were demolished to increase the firing line and -angle.

The headquarters of the Festung commandant were located in the dungeons of the Taschenbastion. Field hospitals were set up under the Hauptbahnhoff and the Stiegauer Platz, (now: Strzegomski Square), together with warehouses for ammunition and foodstuffs. There was no lack of the latter, but there was a shortage of ammunition, mostly artillery shells.

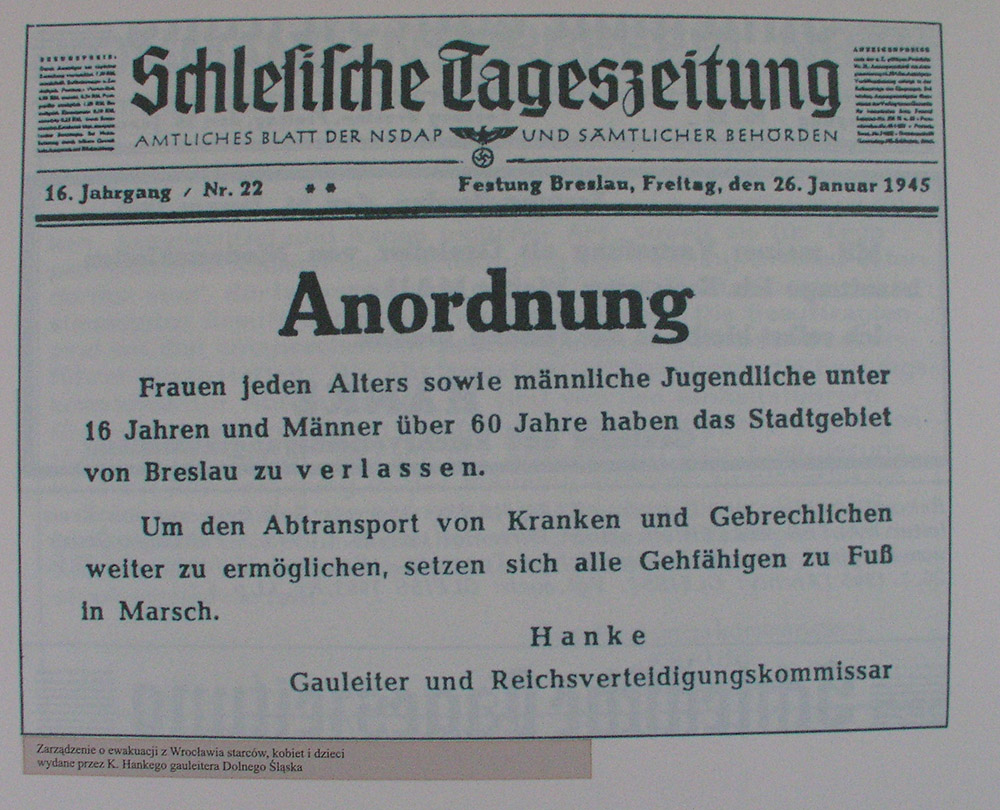

News item from the NS-Amtsblattes Schlesische about the evacuation of civilians from Breslau. January 26, 1945. Source: Wroclaw University Museum

Also in the vicinity of Breslau, fortifications were built. The construction of new defence lines began at the end of July and the beginning of August 1944. The most distant defence lines (up to 40-60 kilometres from Breslau) were ‘Hubertus’, ‘D-1’ and ‘D-2’. Their purpose was to prevent direct artillery fire on Breslau. The construction of another defence line ‘Bartholdt’, situated 20-25 kilometres distance from the bridges across the Oder, began on August 2, 1944. ‘Bartholdt’ consisted of an anti-tank ditch, trenches, machine gun nests and minefields. An outer defence line was created in the northern part of Breslau.

In the summer of 1944, the Breslau population was forced to perform a considerable part of the construction work. However, this did not lead to the desired results and soon forced labourers and POWs were employed for this task.

Simultaneously with the building of new fortifications, the formation and mobilisation of fortress units also began. On January 17, 1945, the following units were mobilized: the Landesschützen-Bataillon 599 and the Festungs-Batterien 3048, 3049, 3075, 3076, 3081 and 3082. To increase the personnel of the Festung, several military police posts were created, with the task of arresting every German soldier (regardless of rank or type of unit), who passed through Breslau. This applied also to civilians who were able to carry a weapon. This tactic proved to be very effective and within a short period of time the 609 Division zBv 'Sachsenheimer' was formed, composed of those who had the bad luck to get caught in this net. These persons were also used as replacements to reinforce combat-battered units, such as the 269 Volksgrenadier-Division.

SA-Obergruppenführer der Volkssturm Otto Herzog, around 1938. Source: Bron: E. Kienast (Hg.): Der Großdeutsche Reichstag 1938, IV. Wahlperiode, R. v. Decker´s Verlag, G. Schenck, Berlin 1938

On the night of January, 18-19, 1945 SA-Obergruppenführer der Volkssturm, Otto Herzog gave the order to prepare units of the first and second category for combat. At the same moment, the formation of the independent fortress-infantry regiments ‘Mohr’, ‘Sauer’, ‘Besslein’ and ‘Hanf’ began. On January 19, the German Army reinforced her tank defences along the Weide River (now Widawa) with additional howitzer batteries.

A Hitler Youth regiment and the SS regiment ‘Besslein’ (which consisted of many Dutch and French volunteers) were sent, later in January, to Breslau to reinforce the Festung’s garrison.

On the night of January 30-31, 1945 Breslau came under fire for the first time by Soviet artillery. That night, shells fell in the Kloster Straße (now Traugutta), the Martha-Straße (Lukasinskiego) and the Blockauer Straße (Swistackiego). The ‘Bethanien’ hospital was hit that night. These bombings increased during the month and resulted in many casualties, mainly since Breslau became a transfer hub for refugees. Notwithstanding the fact that the inhabitants of Breslau had already been ordered to leave the city, many of them were still in the city during those last days of January. To clear the sity completely of civilians, the commander of LVI Panzer Korps, General der Kavallerie Rudolf Koch-Erpach, issued the following order.

‘All children and women below the age of 40 years wil be removed from the Festung, in agreement with the defence commissioner of the Third Reich, starting from the morning of February 1, 1945’.

Sanctions were tightened and executions became more and more a part of daily life in Breslau. Those who were not in possession of the correct papers could expect the worse when arrested within the city limits. Breslau's vice mayor, Dr. Wolfgang Spielhagen, was executed by order of Hanke on January 28, 1945.

Around 700.000 persons left Breslau in January and February 1945, and 100.000 of those did not survive the terrible journey to the west. It meant that almost 230.000 civilians remained within the borders of the Festung.

Definitielijst

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- machine gun

- Machine gun, an automatic heavy quick firearm.

- regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

The Vistula-Oderoffensive

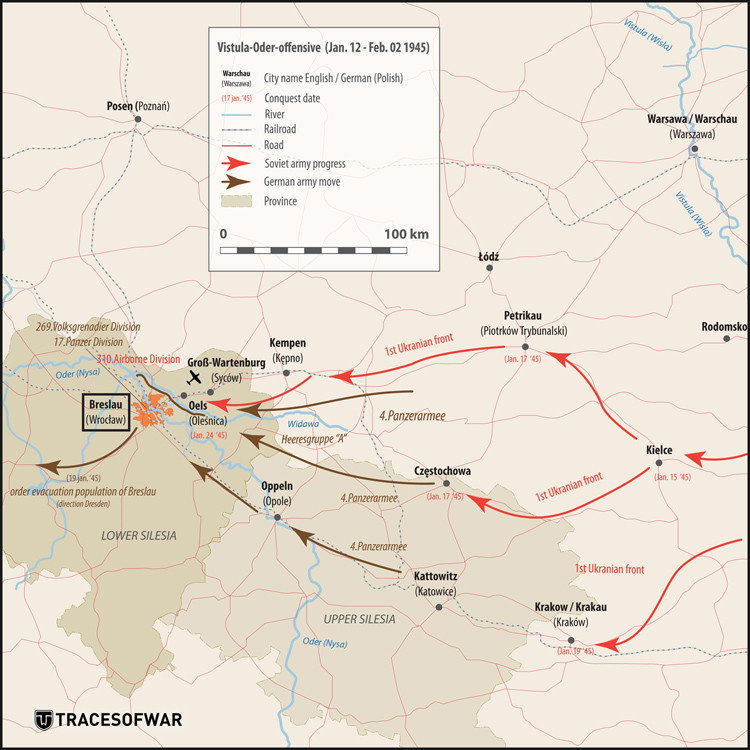

On January 12, 1945, the Red Army launched its Vistula-Oder offensive. The First Ukrainian Front led this offensive under Marshall Ivan Kovey, later reinforced with the First Belorussian Front of Marshall Georgy Zhukov. The 4th Panzerarmee, under the command of General der Panzertruppe Fritz-Hubert Gräser, tried with great force to stop the attack of the First Ukrainian Front, but after only hours of heavy fighting, the German defence line was breached in various places and the road to Breslau was open. On January 15, Kielce was taken by the Red Army, Rodomsko and Czestochowa followed two days later, then Piotrkow Trybunalski fell to the Soviets on January 18. On January 19, the most important city Kraków was captured from the Germans.

On this day, the inhabitants of Breslau were forced by an order of Karl Hanke to leave their houses and head for Dresden. At the beginning of 1945, Breslau was filled to capacity with refugees from areas, east of the city and that caused much disruption and chaos. A great number of them perished in the cold during this difficult journey. Others, who reached Dresden safely, would meet another horror scenario, namely the Allied bombing of that city, a few weeks later.

Generalfeldmarschall Ferdinand Schörner decided to withdraw his Heeresgruppe 'A' in the direction of the Oder River. The Germans however, were seriously hampered in this retreat, leaving the only escape route in the direction of Breslau between Kempen (Kepno), Groß-Wartenberg (Sycòw) en Oels (Olesnica). It did not take long before this escape route too was blocked, as a result of which, many German units became trapped in the so-called ‘Sycòw pocket’. Oels was the last major city before Breslau and therefore of tactical value, to both the Red and the German Armies. The 269. Volksgrenadierdivision was given the task of defending this city and was supported by the 17. Panzer-Division. On January 22, a large-scale air and ground barrage was launched on Oels. This barrage was so intense that the explosions could be heard as far away as Breslau. On January 24, Oels and its airfield were taken by the Red Army after two days of heavy fighting.

General der Infanterie Otto Wöhler (left) and Generalfeldmarschall Ferdinand Schörner (right). April 1944. Source: Bundesarchiv Bild 183-2007-0313-500

The battered 269.Volksgrenadier-Division retreated to the northeastern outskirts of Breslau and took up positions on the left bank of the Widawa River.

Due to the tactical value of Oels, this town was chosen by the Red Army as one of the most important transfer hubs for medical supplies, transport, ammunition and fuel to the units of the First Ukrainian Front, preparing for the attack on Breslau. The captured airfield was used by the 310th Air Division as a base and many of the larger buildings in the town were converted into field hospitals.

Definitielijst

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

A new commander for Festung Breslau

On February 2, 1945, Gauleiter Karl Hanke swore in newly formed Volkssturm units in Breslau. Meanwhile, the Festungskommandant Krause was incapacitated by pneumonia, and he required immediate replacement. This replacement came in the form of Generalmajor Hans von Ahlfen. He was personally selected by the supreme commander of Heeresgruppe 'Mitte', Generaloberst Ferdinand Schörner. His first official announcement to his troops was as follows:

‘On February 2, 1945, at 10:20 in the morning, I have taken over the tasks of the new commander of Festung Breslau".

The newly formed Volkssturm-units in Breslau, sworn in by Gauleiter Karl. February 2, 1945. Source: Bundesarchiv Bild 183-1989-1120-502

Immediately after his appointment, von Ahlfen went to work. A corps staff was assigned to him, due to the large number of units under his command. His first order concerned the reinforcement and reorganization of the units, stationed in Breslau and the formation of units that were specially trained in urban combat. As a direct result of an inspection, the type of camouflage for the units was modified. Also, new fortifications west of Breslau were built.

Von Ahlfen exchanged his VIII Military District headquarters for the underground bunker in the Liebichshöhe and from there he gave the order to blow up 40 of the 66 bridges in and around Breslau.

German troops, retreating to Breslau. February, 1945. The photo shows a Zugkraftwagen 1 t (Sd.Kfz. 10). Source: Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H26408

On February 3, the Festungs-Infanterie-Regiment ‘Mohr’ replaced the weakened 269 Volksgrenadier Division, which was responsible for the northwestern defence sector. At the same time, the Festungs-Infanterie-Regiment ‘Sauer’ was stationed north of the left wing of ‘Mohr’. Festungs-Infanterie-Regiment ‘Besslein’ was stationed in the sector Weistritz-Breslau Lissa and Festungs-Infanterie-Regiment ‘Hanf’ (supported by Festungs-Infanterie-Regiment ‘Wehl’) south of Besslein. The sector Klettensdorf-Herzogshufen-Brockau-Steine was defended by the infantry regiments ‘Reinkorbe’, ‘Kersten’ and ‘Schultz’.

While the mobilisation was in full swing, work began in Breslau on an armoured train. This work took place first in the FAMO factory and later on in the DOLMEL factory. The train was armed with four 88 mm cannons, flak artillery (one 37mm) and one four-barrel 20mm) and two heavy machine guns. The personnel consisted of 108 soldiers and civilian railway workers. The train was renamed ‘Porsel’, after its construction supervisor.

Definitielijst

- artillery

- Collective term for weaponry that fires projectiles. The modern term artillery mainly designates guns in general from which the range and calibres are outside certain boundaries. Artillery is also the name of the army unit which mainly operates such guns.

- flak

- Flieger-/Flugabwehrkanone. German anti-aircraft guns.

- Gauleiter

- Leader and representative of the NSDAP of a Gau.

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

The encirclement

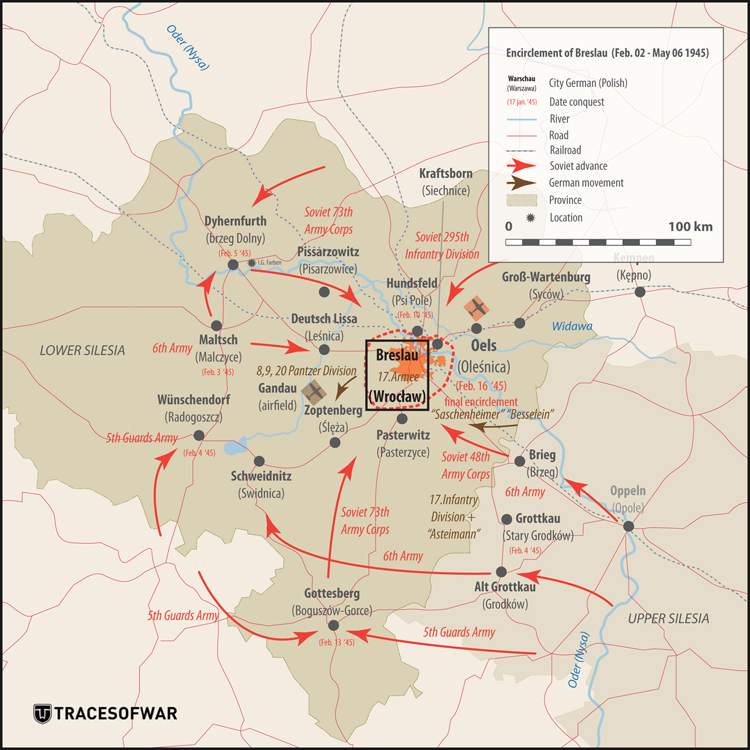

The Soviet armies, assigned to encircle and eventually capture Breslau were the 6th Army (under general Vladimir Gluzdovsky), the 5th Guards Army (under general Aleksei Zhadov) and the 21st Army (under lieutenant-general Konstantin Gusev). This assault group was supported by two fighter corps, one bomber corps and one assault corps from lieutenant general Stepan Krasovsky’s 2nd Air Army.

The 6th Army, with the support of the 7th Mechanized Guards Corps was ordered to attack Breslau from the east, and the 5th Guards Army was to attack from the southeast. The target for both armies was Schweidnitz (Swidnica), 50 kilometres southwest of Breslau.

Facing the Soviet Sixth Army, was the 17. Infanterie-Division, supported by Volkssturm battalions and elements of the CVII Panzerkorps. Opposite the Soviet Fifth Guards Army were the 269 Volksgrenadier-Division, Kampfgruppe 'Asteimann' and assault groups, consisting of military students. They had several tanks and tank destroyers at their disposal. The 17. Armee, which was responsible for the defence of Breslau, kept the 208. Infanterie-Division and the 311. Sturmbrigade in reserve. The 17. Armee could also count on the support of the Luftwaffe, which had better airfields at its disposal than the Red Army’s air force.

At the end of January, the Soviet 37th Army Corps captured the bridgehead across the Oder near the village of Pissarzowitz (Pisarowice). The Soviet 48th Army Corps crossed the frozen Oder southwest of Breslau, 12 kilometres from the city. Apart from this, the First Ukrainian Front captured and reinforced the Steinau bridgehead, north of Breslau.

On the night of February 3-4, units of the Soviet 6th Army took up positions on the bridgehead near Maltsch an der Oder (Malczyce). Not much later, the weather deteriorated in favour of the Germans. On the night of February 4-5, Kampfgruppe ‘Sachsenheimer’ launched an attack on Dyhernfurth (Breg Dolny). Since 1939, a production plant of the chemical concern ‘I.G. Farben’ had been located here, where tabun- and sarin battle nerve gases had been developed since 1942. The attack was split into two groups, one of which deployed storm boats. As soon as the Soviets caught sight of the Germans, they launched a chaotic counter-attack, that was repulsed by the Germans. While the infantry kept the Soviets at a distance, German sappers destroyed key factory parts and also dumped a stock of nerve gas into the Oder. The attack proved a success for the Germans and the commander of this assault group, Generalmajor Max Sachsenheimer, was awarded the Ritterkreuz mit Eichenlaub und Schwertern (Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords).

On February 4, the Soviet 5th Guard army and the 21st Army attacked from the Linden (Lipski) and Wünschendorf (Radogoszcz) bridgeheads and reached the city of Brieg (Brzeg) 50 kilometres south-east of Breslau, where they surrounded a German garrison of 3.000 troops. The Germans, however, refused to capitulate and launched a counter-attack on the next day. That same day, the Soviet 31st Mechanized Corps met the Soviet 5th Army at Grottkau (Grodkow), 20 kilometres south of Brieg. On February 6, another German counter-attack took place. This assault group, consisting of the 45th Volksgrenadier Division and 8. Panzer Division advanced towards Alt Grottkau (Stary Grodkow). During the ensuing fights, this village changed occupiers several times and was eventually captured by the Red Army.

On February 7, the German Army launched a major counter-attack with mechanized troops on the bridgehead of Maltsch, where the Soviet 6th Army had concentrated its forces for the attack on Breslau. This attack was repulsed twice by the Soviets, but the third German attack reached dangerously to Maltsch. Eventually, a well-organized Soviet counter-attack with tanks stabilized their situation.

On Februari 8, the Soviet 74th Army Corps approached Breslau from a distance of 8-10 kilometres. The next day the Soviet 7th Army Mechanized Corps advanced along the Breslau-Berlin highway and started to encircle Breslau from the south. This advance was temporarily halted by counter-attacks of a German assault group consisting of the 19th Panzer Division, the 20th Panzer Division and a number of reserve battalions. During this German counter-attack, the Soviet 57th and 25th Mechanized Brigades of the Soviet 7th Army were cut off from the rest. Eventually the Soviet reserve units stabilized the situation.

The Gauleiter and Oberpräsident Karl Hanke demands the defence of the city to the last man. Shown here: a poster of the first days of February 1945. Source: Bundesarchiv Bildt 183-H29355

On February 10, Soviet troops approached Breslau and clashed with the independent fortress infantry regiment ‘Mohr‘ in the residential area Sakrau (Zakrzow) of the Hunsfeld (Psie Pole) district. On that day, elements of the Soviet 295th Rifles division broke through the German defence lines, threatening the Hunsfeld train station. The German infantry regiment ‘Mohr’, had great difficulties coping with this Soviet assault group, on which the commander of the Festung decided to employ the independent fortress regiment ‘Wehl’ to support ‘Mohr’. On February 11, the German regiment ‘Wehl’ launched an attack on the Soviet positions in the ‘Mohr’ section. The bloody fighting that ensued lasted no less than 4 days. At the same time, a large German counterattack took place elsewhere, carried out by the 609. Festung-Division, the 269. Volksgrenadier-Division, the 208. Infanterie-Division and 10 Volkssturm battalions. Both counterattacks resulted in a temporary halt to the Soviet advance.

On February 13, the Soviet 5th Guards Army and the 6th Army met at Gottesberg (Boguszow). Breslau was now completely encircled. That situation turned out to be only temporary when two mechanized Soviet corps were transferred to the Gorlitz front. The Germans saw their chance and attacked immediately. The 8th, 19th and 20th Panzer-division attacked from both sides of the Zobtenberg (Sleza). The 19 Panzer Division even succeeded in opening a corridor to Festung Breslau and keeping it for a couple of hours. Thanks to this, several German front units were able to withdraw from the city.

On February 15, the German infantry regiment ‘Mohr’ withdrew behind the Widawa river. Kampfgruppe ‘Sachsenheimer’ and SS-regiment ‘Besselein’ were also forced to withdraw. That same day, the Festungscommandant Hans von Ahlfen ordered all citizens in Breslau (regardless of gender or age) to take up arms. He ordered also that excessive waste of petrol had to be avoided. On the night of February 15-16, the Luftwaffe resupplied Breslau by air for the first time. Every night, Ju 52/3m or Heinkel 111H would provide the city with 40 tons of resources. During the siege, the Red Army would position about 320 light and medium anti-aircraft guns, 150 anti-aircraft machineguns and 80 searchlights around the Festung, to impose an air blockade on the Germans. During the day, dogfights took place over the city.

On February 16, the Festung Breslau was finally encircled by the First Ukrainian Front. In addition, Hundsfeld, Sakrau (Gogolin), Pasterwitz (Pasterzyce), Deutsch Lissa (Lesnica), Kanthen and Kraftborn (Siechnice) fell into the hands of the Red Army.

Definitielijst

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Kampfgruppe

- Temporary military formation in the German army, composed of various units such as armoured division, infantry, artillery, anti-tank units and sometimes engineers, with a special assignment on the battlefield. These Kampfgruppen were usually named after the commander.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

Line of battle of the Festung Breslau Garrison. 1 February 1945

Garrison Festung Breslau

| - Commandant | Generalmajor der Artillerie Johannes Krause |

| - SS-Festungs-Grenadier-Regiment ´Besslein’ | Obersturmbannführer Georg-Robert Besslein |

| - Festungs-Grenadier-Regiment ‘Hanf’ | Rittmeister Karl Hanf |

| - Festungs-Grenadier-Regiment ‘Mohr’ | Major Walter-Peter Mohr |

| - Festungs-Grenadier-Regiment ‘Sauer’ | Oberst Hermann Sauer |

| - Festungs-Grenadier-Regiment ‘Wehl’ | Oberst Wolfgang Wehl |

| - 609.Division zBv ‘Sachsenheimer’ | General Siegfried Ruff |

| - Artillerie-Regiment ‘Breslau’ | Oberst Urbatis |

| - Pionier-Regiment ‘Breslau’ | Major Hameister |

Definitielijst

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

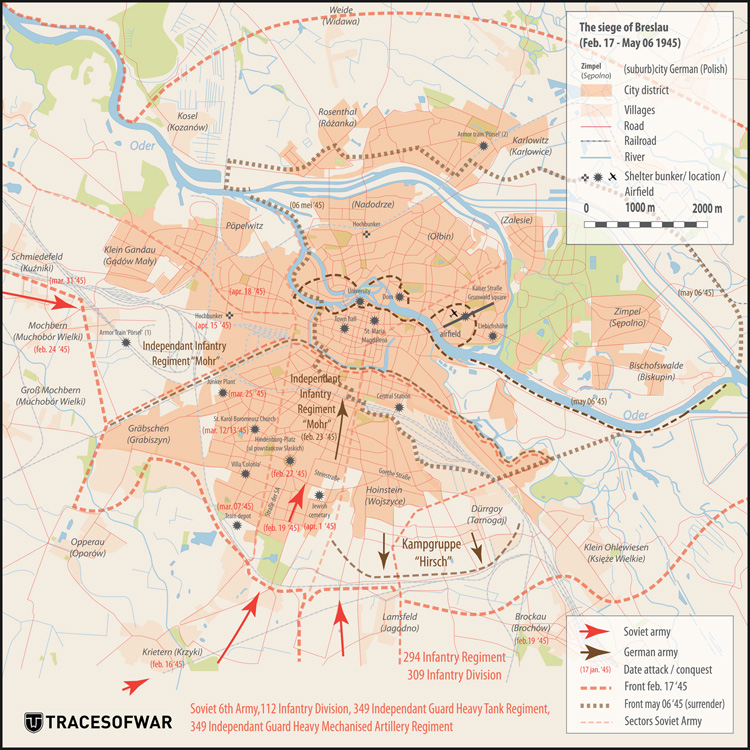

The Siege (February 1945)

The troop strength of the besieged Festung Breslau was 50.000 men (including 15.000 Volkssturm). The German units were well prepared, but lacked experience and had a shortage of tanks and artillery. General Vladimir Gluzdowski (Soviet 6th Army) estimated that there were about 65.000 troops, 559 pieces of artillery, 534 mortars, 37 tanks/tank destroyers and nine armoured cars in the Festung. The Soviet 6th Army, severely depleted by transfers and losses, only had 48.000 troops at its disposal.

The Soviet 6th army that besieged Breslau allowed Generalmajor von Alhfen 24 hours on February 16 for the Festung to capitulate. No answer came. The next day, the Soviet 6th Army was reinforced by the 294th Fighter Division and the 77th Field Fortification Section. That same day the first direct attack on Breslau, between Neukirch (Nowy Kosciol) and Brockau (Brochow) was launched. Heavy fighting ensued on the railway embankment in the city district Krietern (Krzyki), behind Breslau’s radio station building. This section was defended by the German independent infantry regiment l‘Wehl’. The Soviet Fighter Regiment (218th Fighter Division) and elements of the 309th Fighter Division were ordered to capture the Breslau radio station building. The Soviets launched various attacks, but each time they were repelled, resulting in their loss of a T-34/85 tank and several SU-76M mechanized artillery pieces. Eventually, the building was captured using a ruse. A reconnaissance company of the 307th Fighter Division, attacking the building, pretended to be German and even wore German uniforms.

Hans von Ahlfen (still Oberst at that time) in 1942. Source: Bundesarchiv B 145 Bild-F016218-0032A

The railway embankment also was eventually captured by the Red Army, which moved the fighting to the north of the city, in the area of the tram depot. There, the Soviets clashed with the 55th and 56th Volkssturm Battalion (part of Kampfgruppe ‘Hirsch’). The tram depot changed hands many times that day, but the German defenders were unable to hold the line and eventually were forced to consider the depot lost.

At the same time, Soviet units, who attacked from the direction of the Hoinstein (Wojszyce) and Lamsf’eld (Jagodno) districts, forced the ´Reinkorber’ regiment of the 609th Division back to the Dürrgoy (Tarnogaj). In addition, the Soviet units attacking from Hoinstein, advanced along the Heidaner Grenz Weg (ul. Dzjalkowa) and the Heindaner Feld Weg (ul. Jableczna). On February 19, the Germans withdrew from Brockau. The Soviets, however, were soon faced with a problem: the more they advanced into the city, the denser the residential areas became, and the number of obstacles and pockets of resistance increased.

On February 20, Breslau was subject to heavy Soviet aerial bombardment and artillery barrages. In the days that followed, fierce fighting ensued for the Strasse der SA (ul. Powstancow Slaskich) and adjacent streets to the south. On February 23, the Soviet 309th Fighter Division captured the cuirassier’s barracks.

The fanatical German defenders used everything they could lay their hands on. They even developed a method to launch U-boat torpedoes from train carriages. On February 23, von Ahlfen ordered the destruction of an entire district in the vicinity of the Kaiser Strasse (now: Grunwald square), in order to construct an alternative runway of 1300 meters long and 300 meters wide. Thousands of civilians and forced labourers were deployed for this project, many of them killed by the incessant artillery barrages and bombardments. It is difficult to imagine that so many would perish for an airstrip that never would be used

On February 24, the Luftwaffe sent a representative, Colonel Von Friedeburg, of the General Staff of General Robert von Greim’s Luftflotte 6, to the city to streamline the Luftwaffe operations for Breslau. That same day, Soviet troops reached the headquarters of the VIIIth Military District, they then advanced towards the railway that ran through the district Groß Mochbern (Muchobor Wielki). The German infantry regiment ‘Wehl’ tried to stop this attack, but failed and lost a good many troops during the fighting. To prevent the Soviets from breaking through the German line of defence, this regiment received assistance from several battalions of the infantry regiment ‘Mohr’. ‘Mohr’ also was confronted with a dire situation, when it was bombed immediately on arrival by Pe-2 bombers and targeted by heavy artillery and rocket launchers.

On the Soviet side, losses now started to become alarming. The German defenders were well hidden and even entrenched in underground tunnels and the sewer system. In buildings, which the Soviets thought they had captured, there still appeared to be German defenders, who, from their precarious situation, tried to recapture the building. When it was clear that a building could not be saved, it was usually blown up with explosives stored in the basement. Human tank destroyers, armed with Panzerfausten and Panzerschrecks, knocked out many Soviet tanks and other armoured vehicles during the first days of the siege.

The Soviets, however, quickly adapted to the situation and replaced their tanks with sappers who blew up barricades and strong points. Additionally, the Soviet 6th Army formed special assault units. These special units consisted of an infantry battalion, supported by two tanks or self-propelled guns, two heavy artillery pieces (152 or 203 mm), a light artillery battery, a sapper unit and a flamethrower platoon.

The Germans also lost many men during this hard fighting around Breslau. In the first week of the siege, 500 soldiers of the German infantry regiment ‘Wehl’ were killed. Additionally, in the same week, another 5000 soldiers were taken, prisoner. The ‘Reinkörber’ regiment was forced to withdraw from some streets, because of serious losses. On February 26, the ‘Mohr’ regiment had to yield half a street. On February 27, Soviet soldiers passed the Hindenburg-Platz (Plac Powstanców Slaskich), prompting the general staff to evacuate all citizens from the Goethe Strasse and the streets south of the Hauptbahnhof.

Dick Delchambre narrates:

My mother was requisitioned as a ‘voluntary nurse’. She saw a lot of blood and many dead and wounded, and what was particularly painful were the young soldiers calling out to their mother. During the war, she was repeatedly at odds with high-ranking officers who did all they could to save their own asses. When she wanted to speak to some officers who were hiding, she lost sight in one eye, due to a piece of shrapnel.

Definitielijst

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Kampfgruppe

- Temporary military formation in the German army, composed of various units such as armoured division, infantry, artillery, anti-tank units and sometimes engineers, with a special assignment on the battlefield. These Kampfgruppen were usually named after the commander.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- rocket

- A projectile propelled by a rearward facing series of explosions.

- U-boat

- The German name for a submarine. German U-Boats (Submarines) played a very important role during the course of warfare until May 1943. Many cargo and passenger ships were torpedoed and sunk by these assassins of the sea.

The siege (March 1945)

On March 1, after a failed counterattack in Dürrgoy, the Germans were forced back to the vicinity of the Gutenberg Strasse. Later that day, the XXXIX and the LVII Panzerkorps of the 4. Panzerarmee launched a series of counterattacks in the direction of Striegau (Strzegom) and Lauban (Luban, east of Breslau) to make the Breslau-Berlin railway accessible. Meanwhile, the 3rd battalion of the Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 26 at Breslau had landed. On March 2, Lauban had been recaptured by the 4th Panzerarmee and inflicted heavy losses on the completely surprised Soviet 3rd Guards armoured army. Due to this attack, a renewed link was established between Southern Germany and Upper Silesia (Oberschlesien) and the Ostrau-Karwin mining region in Moravia (Eastern Czech Republic). However, the main objective of the 4th Panzerarmee was to launch from there another counterattack, which was to break the siege of Breslau. The rapid action of the Red Army, however, prevented this, and these plans were never carried out. Between March 3 and 4, the 2nd battalion of Falschirmjäger Regiment z.b.V. ‘Schacht‘ landed in Breslau.

The fact that the Soviet 6th Army had penetrated deeply into the southern part of Breslau, was considered dramatic by the General Staff of Vem>Armeegruppe ‘Mitte’.

Generalfeldmarschall Ferdinand Schörner, the supreme commander of Heeresgruppe A and nicknamed ‘Bloody Ferdinand’, decided that Festung Breslau needed a more powerful commander, who reacted more aggressively and effectively on Soviet Actions. Apart from that, Schörner was convinced that Generalmajor Hans Von Ahlfen was too submissive to Gauleiter Hanke and therefore needed a more independent commander, who was more devoted to him. With this in mind, Schörner appointed General der Infanterie Hermann Niehoff, to replace Von Ahlfen as commander of Festung Breslau. On March 6, Niehoff landed on the Gandau (Gadow) airfield and arrived unannounced at the Festungs-headquarters, below the Liebichshöhe. The surprised Von Ahlfen handed over his command to his successor and outlined to him the situation on the Breslau front. On March 8 Niehoff officially declared that he was the newly appointed commander of Festung Breslau. Two days later, von Ahlfen left Breslau by plane,

From the moment that Niehoff was appointed commander of Festung Breslau, the period of rapid territorial gains for the Red Army was over. The Germans, who became more fanatical every day, forced the Soviets into bloody fighting for every house, street barricade and bunker. Flamethrowers and heavy explosives proved to be of little effect and other attempts to capture important defence sectors failed.

At the beginning of March 1945, most heavy fighting was done in and around the Bernhardin, Tarnogajska, Herderstraße, Elazna, Sudecka streets and the St. Karol Boromeusz church. This church was defended by a garrison of 40 men, armed with two heavy and four light machine guns, together with Panzerfausts. Every attempt by the First Battalion of the Soviet 957th Fighter Regiment to capture the church failed. Eventually, the church with its German garrison was blown up by Soviet sappers on the night of March 12-13. On March 7, fierce fighting broke out around several cemeteries in the south of the city and the tram depot on Seinstrasse. This tram depot changed hands various times and was eventually captured by the Red Army, who drove the German defenders back to Steinstrasse. That street was defended by elements of the ‘Kersten’ regiment, whose main point of resistance was a concrete school building. Finally, Soviet troops forced their way into the school using flamethrowers and bitter fighting ensued for every schoolroom.

On March 19, the Soviet 22nd Fighter Corps reached several streets and intersections, while the Soviet 74th Fighter Corps, with the aid of the 359th Fighter Corps, captured the Gräbchen (Grabiszynek) District. The Soviet 74th Fighter Corps made contact with the left wing of the Soviet 22nd Fighter Corps, which captured the district Herrnprotsch (Pracze Odrzanskie) with units of the Soviet 181st Fighter Division. North of Breslau the Soviet 294th Fighter Division captured the villages Weide (Widawa), Leipe Petersdorf (Lipa Piotrowska) and Polanowitz (Polkanowice).

In mid-March, the German defenders launched a counter offensive to isolate Soviet units in the district Mochbern (Muchobor) and to break through to the Zobtenberg (de Sleza). From March 20, this offensive was supported by the German armoured train ‘Porsel’, which moved on the Schmiedefelt-Mochbern route. The same armoured train also supported German units during fights around the airfield near Gandau. According to German sources, the train would have destroyed ten Soviet tanks and three aircraft after ten days of fighting. Eventually,’ Porsel’, was knocked out by heavy Soviet artillery fire. The undercarriage was severely damaged and about 30% of the crew were killed. The wreck was taken out of combat for repairs and to make up for losses. After repairs, the armoured train was deployed on the Karlowitz-Rosenthal route.

On March 25, with armoured cars and artillery, the Soviet 218th Fighter Division, attacked the ‘Junker’ factory (situated between the Gräbchener Straße and the railway to Königszelt/Jaworzyna Slaska). After four days of heavy fighting, the factory was taken by the Soviets. On March 29, the Polish 2nd Army arrived in Trebnitz (Trzebnica), about 20 kilometres north of Breslau, in preparation for entering the battle for Festung Breslau, On March 31, the city districts Maria-Höfchen (Nowy Dwor) and Schmiedefeld (Kuzniki) were captured by the Red Army, and the German defenders were driven out of Groß Masselwitz (Maslice Wielkie), endangering the Gandau airfield.

Definitielijst

- Armeegruppe

- Usually consisted of two or three neighbouring Armees, sometimes German and Axis-allied Armees. One Armee HQ, usually the German, temporarily became the commanding HQ of the other Armees. An Armeegruppe would always be subject to a Heeresgruppe. Later in the war the size of an Armeegruppe or Panzergruppe varied significantly. From 1943 onwards an Armeegruppe could be the size of an Armee or just the size of a corps.

- Fallschirmjäger

- German paratroopers. Part of the Luftwaffe.

- Gauleiter

- Leader and representative of the NSDAP of a Gau.

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- Junker

- “Junger Herr”. Young master, young lord. German nobility and/or land owners. A great deal of influence in the army and in politics.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

The siege (April Offensive and German capitulation)

For the planned Soviet April offensive, the weakened Soviet 6th Army was reinforced with the 112th Fighter Division, the 87th Independent Guards Heavy Tank Regiment and the 349th Independent Guards Heavy Mechanized Artillery Regiment. The Gandau airfield, situated in line of the attack, was defended by the Vem>Kampfgruppe 'Tilgner' and the Independent Infantry Regiment ‘Mohr’, which had entrenched themselves in hastily improvised defensive position west of the airfield. In the vicinity of the airfield itself, two Fallschirmjäger battalions (Kampfgruppe ‘Trotz’ and ‘Skau’), armed with an 88 mm FLAK battery and 20 mm guns from damaged planes. The German Third Tank Destroyer Company and Kampfgruppe ‘Wolf’ were also positioned there.

On April 1, the second offensive against Breslau broke out. This offensive was preceded by air bombardments on the outer defence lines and the city centre. In addition, a 90-minute artillery barrage took place. After this artillery barrage, Soviet infantry, supported by tank destroyers and heavy tanks, attacked the western defence sector. The Soviet 359th and 294th Fighter Divisions overran the German defenders on the railway embankment and during the afternoon advanced deep into Gandau and the airfield. In the south, the Red Army launched an attack in the vicinity of the Jewish cemetery Kozanow and West park, during which a large section of the ‘Mohr’ regiment was cut off from the main force. These cut-off soldiers entrenched themselves, together with their commander and the remainder of Kampfgruppe ‘Wolf’ in the Institute for the Blind. The fighting for the group of buildings lasted for three days before the last German defenders surrendered. The remainder of the ‘Mohr’ regiment retreated to the other side of the Oder, near the village of Ramsem (Redzin). At the same time, the Soviet 74th Corps pushed through the German defence line, after which the Soviet 181st and 112th Fighter Divisions were involved in the heavy fighting around the buildings of the Linke-Hofmann Werke and the FAMO factory.

The breakthrough in the western sector turned out to be dramatic for the Germans. Not only were they forced back three kilometres, but the airfield also had been lost, making it impossible to evacuate the wounded and the Luftwaffe support was severely hampered. The German pilots had no option, but to drop goods at night at random, risking that they would fall into Soviet hands.

On April 4, the Polish 2nd Army was ordered to take part in the Berlin offensive, leaving the Soviet 6th Army on its own to capture the Festung Breslau. During this period the Germans began to reorganize themselves and reinforcements were sent to the sector under attack. The territorial gains for the Red Army eventually proved also to be beneficial for the defenders, because the closely built-up area provided the possibility for ambushes and proved also to be a hindrance for Soviet tanks and mechanized artillery. Heavy fighting took place mainly around the Debowy-park, which was not captured until April 12.

On the night of April 5-6, the commander of Festung Breslau, Hermann Niehoff, evaluated the situation at the front. He reported to the supreme commander Ferdinand Schörner that the Volkssturm troopers were in a state of panic and the citizens were in despair. In turn, Schörner sent Niehoff’s message to Adolf Hitler. After reading this report, Hitler ordered that the Festung must be held to the last man. He did, however, intensify the air supply for the Festung.

After the capture of the Debowy-park, on April 12, the Soviets forced the Germans behind the railway line and clashed with elements of the German infantry regiment ‘Mohr’. These German units succeeded in stopping the Soviet attack at least temporarily. On April 15, the Soviet 135th Fighter Division was thrown into battle. After three days of fighting, this division captured thirteen blocks and the 25-metre high air raid shelter at the Striegauer Platz (Plac Stregomski). This bunker housed the IIB Hospital and was defended by a group of fanatical Waffen-SS soldiers, armed with heavy machine guns, grenades and Panzerfausts. The Soviets launched many bloody attacks against this bunker and eventually captured it after deploying heavy artillery.

On April 15, a large-scale German regrouping took place and the German infantry regiment ‘Besslein’ and the 509. Division were relocated in the western sector. On April 18, the Red Army took up positions in the Posener Straße (ul. Poznanska). Eventually, these troop replacements stabilized the front. The Soviet 6th Army seized its offensive at the end of April and took up defensive positions. The units of this army became too thin and the soldiers were too tired to function any longer. Apart from that, the First Ukrainian Front was already fighting in the Berlin streets and it was merely a question of time, before the German Army would capitulate. The last days of the siege were characterized by artillery barrages and a propaganda "offensive" with pamphlets and loudspeakers. During this phase, battle fatigue began to show among the population of Breslau. More and more, white flags began to appear, accompanied by daily executions by SS Sonderkommandos.

Dirk Delschambre, whose mother lived in Breslau, describes the final phase of the siege:

'During the final offensive, there had been a brief armistice in which the ‘last inhabitants’ were given the chance to either stay in the city and to adopt automatically the Polish nationality, or remain German citizens and move straight to the west. There were very large storage bunkers with food. These were opened during the armistice and the remaining population could take what they wanted. My mother and others had never seen such enormous food supplies. This bunker was apparently built in a special way, namely on a water bed or rubber bed, which made it bomb-free. When it was opened, the population was particularly affected by this secret, because people had nothing to eat. They did not want the supplies to fall prey to the Russians'.

People could go on transport with a maximum of 20 kg of luggage on two trains (that is: cattle wagons that were used previously for other means). After a couple of days, they arrived at Amsberg/Westphalia where they were interned in a former camp.

On May 4, representatives of the Reformed and Roman-Catholic churches in Breslau tried to convince Hermann Niehoff that further resistance was futile and that the best thing to do was to capitulate. The commander of Festung Breslau did not want to hear of this (yet). On May 5, Karl Hanke, appointed Reichsführer-SS by Hitler on April 29, fled from Breslau and took a plane to Prague. A few months later, he would die a violent death, presumably shot dead by Czech guards while attempting to escape from a POW transport.

On the night of May 5-6, a German antifascist sabotage-unit called the ‘Committee for a Free Germany’, led by Leutnant Horst Viedt, succeeded in slipping through the frontline. This covert operation ended in a fiasco including the death of 10 saboteurs, including the commander.

Delegation of German officers, just before the negotiations for the capitulation of Festung Breslau, May 6th, 1945 Source: Ryszard Majewski, Wrocław - godzina zero, Wrocław, 1985

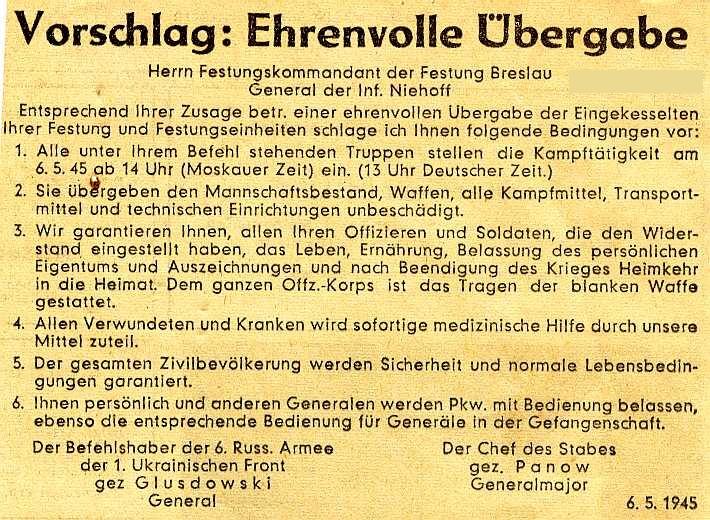

Early in the morning of May 6, Niehoff informed the Soviet 6th Army that he wanted to negotiate a possible capitulation. Representatives of both parties met each other at the intersection of Straße der SA (Powstancow Slaskich) and the Viktoria Straße (ul. Lwowska). The representatives of the Festung were Hauptmann Von Bruck and Oberst Tiesler (deputy commander). The Soviet representatives were Major Omar Yakhaev and Colonel V. Chichin of the 22nd Corps. The Soviet officers arrived in the afternoon at Niehoff’s headquarters. At their request, Niehoff and his staff crossed the frontline and arrived at Villa ‘Colonia’, the headquarters of the Soviet 22th Corps, at Kaiser Friedrich Straße 14 (ul. Rapackiego). There the commander of Festung Breslau signed the capitulation of his troops, at 6:20 p.m. At 9:00 p.m. the first Soviet units arrived in the centre of Breslau. The battle of Breslau was over.

Definitielijst

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- Destroyer

- Very light, fast and agile warship, intended to destroy large enemy ships by surprise attack and eliminating them by using torpedoes.

- Fallschirmjäger

- German paratroopers. Part of the Luftwaffe.

- FLAK

- Flieger-/Flugabwehrkanone. German anti-aircraft guns.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Kampfgruppe

- Temporary military formation in the German army, composed of various units such as armoured division, infantry, artillery, anti-tank units and sometimes engineers, with a special assignment on the battlefield. These Kampfgruppen were usually named after the commander.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- POW

- Prisoner of War.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

Aftermath

On May 7, the Germans who were made POWs were transported to a camp near Hunsfeld. In Moscow, the capitulation was celebrated with a 224-gun salute. The official announcement of the Soviet high command read as follows.

Breslau is taken. On May 7, after a prolonged siege, the units of the First Ukrainian Front gained full control of the city and the fortress. The German garrison, which defended the city has, together with their commander, Infantry General Niehoff and his staff have given up resistance and laid down their weapons and capitulated.The general staff of the 17.Armee sent the following radio message to the Festung:'It is with feelings of pride and grief that Germany’s banners are lowered in tribute to the steadfastness of the garrison and the self-sacrifice of the population of Breslau"

Immediately after the capitulation, there was nothing much left of the once proud Breslau. Of the 30.000 buildings, 21.600 were ruined or (heavily) damaged. Around 60% of the industry and 80% of the tram network and gas supply had been destroyed. On capitulation day the whole area was covered with 18 million tons of rubble.

According to the estimate of the British historian Norman Davies, 170.000 German citizens lost their lives. Other estimates speak of 20.000 civilian deaths. The German losses amounted to around 6.000 killed and 23.000 casualties. Additionally, 45.000 German were made prisoners. The ‘Luftflotte 6’ lost 147 planes and 61 were damaged, between February 15 and April 25, 1945. For the already weakened Luftwaffe, this was a horrific loss. SA-Obergruppenführer Otto Herzberg. Commander of the Volkssturm-units in Breslau committed suicide on May 6, 1945.

According to Soviet sources, the mechanized artillery- and tank units of the Soviet 6th Army would be responsible for the elimination of:

| Materiel and Personnel | Captured | |||

| Tanks: | 2 | Artillery pieces: | 3 | |

| Artillery pieces of various calibres: | 36 | Mortars: | 6 | |

| Mortars: | 22 | Heavy machine guns: | 5 | |

| Heavy machine guns: | 82 | Motorcycles: | 3 | |

| Hand weapons: | 210 | Bicycles | 52 | |

| Machine gun nests and bunkers: | 7 | Prisoners | 123 | |

| Soldiers and officers: | 3.759 | |||

Exactly how many men the Red Army lost in the battle for Breslau, cannot be determined with certainty until this day. Shortly after the capitulation, a temporary cemetery was established south of Breslau, for 6.000 Soviet fallen. However, this was not the only temporary cemetery in the vicinity of the city. The following diagram summarizes the irreparable losses of the mechanized artillery- and tank units of the Soviet 6th Army during the siege of Breslau.

| T-34 | IS-2 | SU-122 | SU-152 | Personnel | |

| Burned out: | 6 | 5 | 3 | 1 | - |

| Hit: | - | 7 | - | 3 | - |

| Mines: | 4 | - | 2 | - | - |

| Totaal: | 10 | 12 | 5 | 4 | 154 |

According to an estimate by Norman Davies, a total of 13.000 Soviet soldiers and 760 officers were killed during the fighting for the Festung. Eventually, the Soviet fallen would be buried in two permanent war cemeteries in the city.After the war, Breslau was annexed to: Poland and renamed ‘Wroclaw’. Most of the German population was driven out of the city or had already fled to the west.

Definitielijst

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Machine gun

- Machine gun, an automatic heavy quick firearm.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

The field of battle today

Those who wish to visit the former Breslau will not have wasted their time. The two Soviet war cemeteries are well worth visiting. The first one, situated at the ul. Karkosona consists of individual and communal graves of 760 Soviet officers, including 6 ‘Heroes of the Soviet Union’. The second war cemetery is situated at the ul. Dzialkowa. Here, no fewer than 7.500 Soviet Soldiers are buried in mass graves. The German fallen are buried in a large war cemetery east of Wroclaw, in the village of Nadolice Wielkie (formerly Groß-Nädlitz).

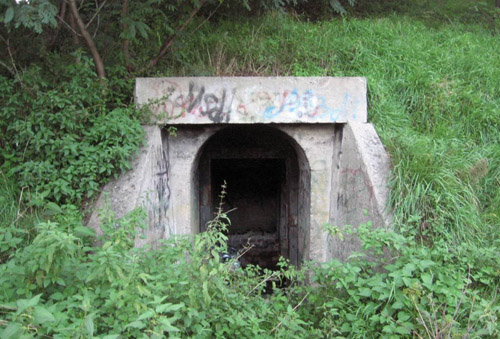

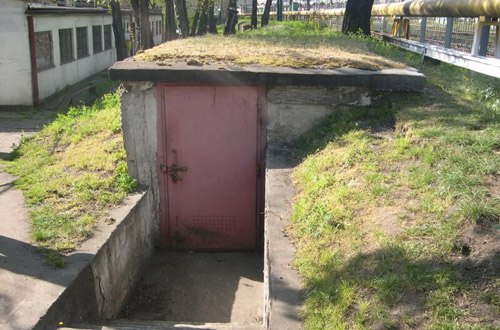

The Villa Colonia, where the German capitulation was signed on May 6, 1945, is still there. Apart from this, there are various shelters and combat positions that can be visited in and around the city. Many of the original German buildings that have survived the fighting, still clearly bear the traces of the battle. Some of them even have Soviet graffiti.

Definitielijst

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Information

- Article by:

- Kaj Metz

- Translated by:

- Cor Korpel

- Published on:

- 21-05-2023

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- DUFFY, C., Red Storm On The Reich, Castle Books, Edison, 2002.

- KRIVOSHEEV, G. F., Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century, Greenhill Books, Barnsley, 1997.

- SOLARZ, JACEK, Breslau 1945, Wydawnictwo Militaria, Warschau, 2007.

- ZIEMKE, E. F., Stalingrad to Berlin, University Press of the Pacific, Honolulu, 2002.

- Axis History Forum

- With thanks to Anne Palmer for her editorial work.