Previous history

Origins

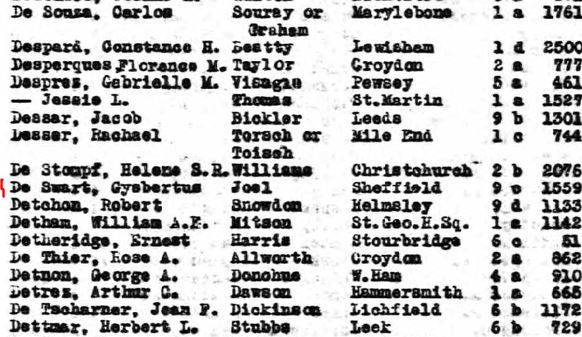

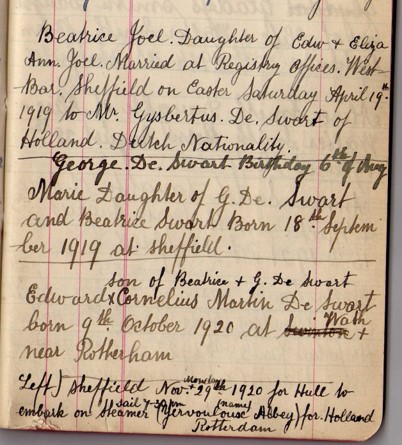

The story of Edward Cornelius Martin Swart began on October 9, 1920 in the village Wath upon Dearne, South Yorkshire, near Rotherham in England. He was named after his grandfathers: Edward on his mother’s side and Cornelis Martinus on his father’s side. Edward was the second child and first son of Gijsbertus de Swart (later also known as George Swart) and Beatrice Swart-Joel. At that time they already had a daughter, Marie (September 19, 1919, Sheffield). In the following years, the family expanded to eight members with Edward’s younger brother Sidney (May 6, 1923, Schiedam), his younger sister Beatrice and his younger brothers Geoffrey (May 3, 1930) and George (1935).

Dutch ‘roots’

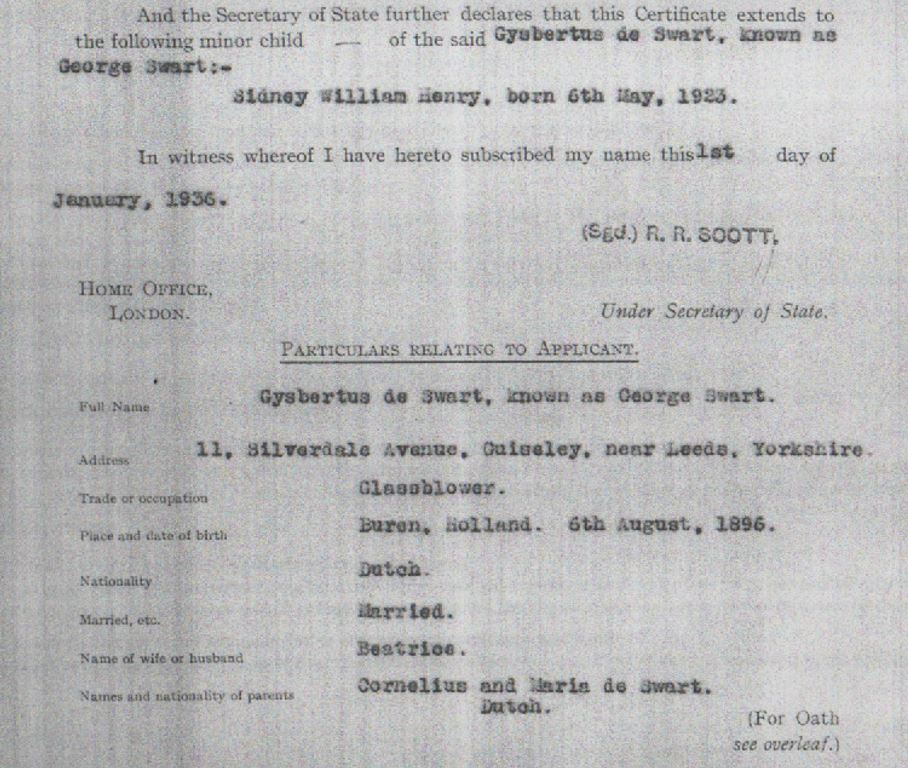

As their surnames suggest, part of the Swart family history lies in the Netherlands. In fact, father Gijsbertus de Swart was born on August 6, 1896 in Buren, Gelderland.[1] In his early years, Gijsbertus moved frequently with his parents. After Asperen (from April 22, 1899)[2], Kedichem (from September 14, 1910)[3] and Nieuwerkerk aan den IJsel (from January 1, 1914)[4] the family finally settled in Schiedam on July 10, 1915.

It is said that Gijsbertus then moved to England to avoid having to serve in the military.[5]. According to the civil registry of the municipality Schiedam, Gijsbertus did remain registered in Schiedam. The rest of the De Swart family also lived in Schiedam until at least 1924, but each child left the town on a different date. Once in England, Gijsbertus married Edward’s future mother, Britain’s Beatrice Joel, in 1919. Beatrice Joel was the daughter of Ed(ward) Henry Joel and Eliza Ann Joel-Cox. Gijsbertus and Beatrice married at the Registry Offices in West Barr, Sheffield on Easter Sunday, April 19, 1919. The same year, their daughter Marie was born.

Returning to Schiedam

Family records[6] show that following the birth of Edward on November 29, 1920, the four-member family left Sheffield shortly thereafter for Hull, to board the Jervaulx Abbey steamer[7] on a voyage to Rotterdam. Edward was three weeks old at the time. Now that the First World War was over, Gijsbertus had no difficulty showing himself again in Schiedam, where he was still registered. It is assumed in the family that Gijsbertus and his family stayed with his parents after their return, with the intention that his stay would last several weeks. However, Beatrice fell ill, which ultimately made this stay last no less than four years. Beatrice had extremely bowed legs, because she had rickets as a child. She may also have had a heart condition. It is unclear how long the family wanted to stay in the Netherlands, but a four-year stay with Edward’s grandparents was certainly not planned. As a result of this extended stay, Sidney was the only child born in Schiedam. Meanwhile, Gijsbertus was working as a gas fitter, according to the civil registry of the Schiedam municipality.

Final destination England…?

Dutch was the first language spoken in the household, but on July 29, 1924, the family relocated again, this time back to Sheffield, to mother Beatrice’s home town. Here they lived happily for the next few years, as more children joined the family.

In the year 1931, factory manager Frank Parkinson travelled to Sheffield to recruit staff for his factory’s glassworks in Guiseley, near Leeds in Yorkshire. Gijsbertus accepted the offer and the family moved again, to Guiseley. Gijsbertus, like his father an experienced glassblower by now, apparently had many Dutch and Belgian friends in Sheffield. Some of these friends came to Guiseley, where their friendships continued. It was partly because of these friendships that a lot of Dutch was still spoken at home.

A few more years passed before Gijsbertus became a British citizen on January 10, 1936, almost twelve years after their immigration to the UK. He would continue to live under the name ‘George Swart’ as he had probably called himself for some time. Sidney, the only child born in the Netherlands, was also naturalised that day. Edward and his siblings, like their mother, would now adopt the surname Swart without the Dutch ‘de’. In 1940, father George had passed away.

Definitielijst

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

Military career

Edward enters military service

After Edward’s childhood in Sheffield and Guiseley, he went straight from school to work in the factory’s glasswork of Frank Parkinson where his father also worked. Generations of his family had passed on the glassblowing trade, but Edward did not enjoy it. So shortly afterwards, he went to work as weaver and storekeeper for Edward Denison and Co. at the Westfield wool factory. This factory was in Yeadon, West Yorkshire, not far from Guiseley. It is not known how long he worked at both factories, but by then the Second World War had begun and the UK was at war.

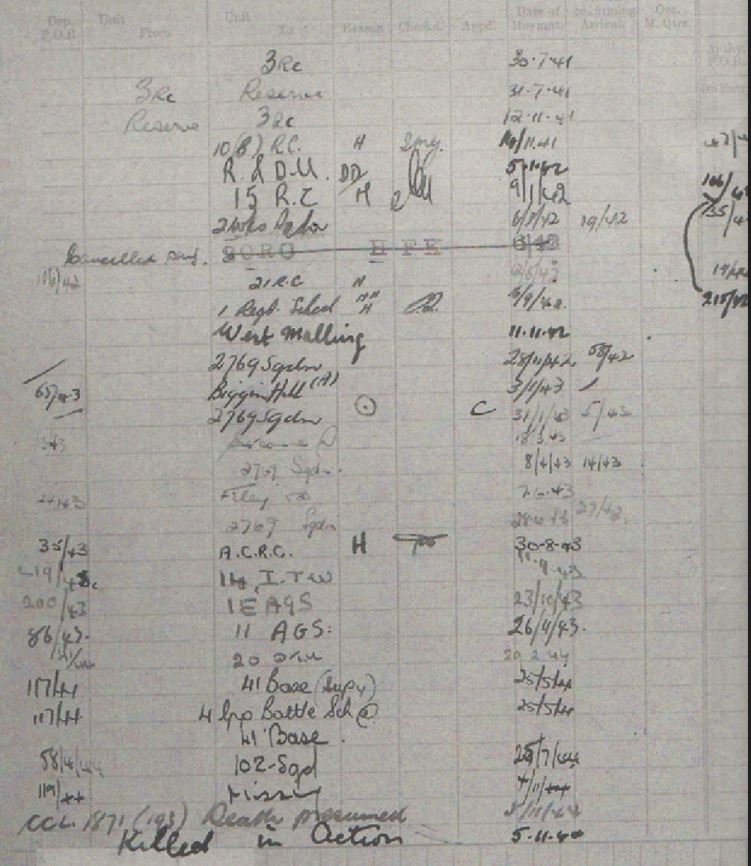

Although there is evidence that his younger brother Sidney joined the British Army (in the Reconnaissance Corps) and his other brother Geoffrey ended up in the Army too, Edward saw more merit in a role in the RAF; so much so that on Wednesday July 30, 1941, he went to the no. 3 recruitment centre RAF Padgate, between Liverpool and Manchester, to enlist in the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. There he received his service number 1486325 and started his military career.

Turbulent times in training

The following years, Edward saw a large part of the UK. His records show, among other things, that via Recruits Centre Blackpool, an Aircraft Delivery Unit and a Reception and Disposal Unit, he finally joined a squadron for the first time on November 28, 1942, the No. 2469 Squadron at West Malling and later Biggin Hill, both south of London. He joined an Initial Training Wing via RAF Hunmanby Moor in the north of England on September 11, 1943, probably at St Leonards in Sea and Bridlington, also in the north of England. It was probably here that Edward’s training officially began. A month later, he entered the Air Gunners School on October 23, where he was trained for his eventual position as an Air Gunner. Through another training unit and a ‘Ferry Pilots Pool’ Edward was assigned to his final squadron, the 102nd ‘Ceylon’ squadron at RAF Pocklington, about 12.5 miles east of York on July 25, 1944. This was already his twenty-fifth entry in his ‘unit file’.

By then, Edward had risen through four promotions and one demotion to Temporary Sergeant, at the time of his Air Gunner School.

Promotions and demotions

- 30-07-1941 Aircraftman Second Class

- 12-05-1942 Aircraftman First Class

- ??-??-???? Aircraftman Second Class

- 01-01-1943 Aircraftman First Class

- 01-08-1943 Leading Aircraftman

- 25-01-1944 Temporary Sergeant (T/SGT)

In the Ceylon Squadron

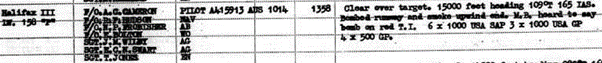

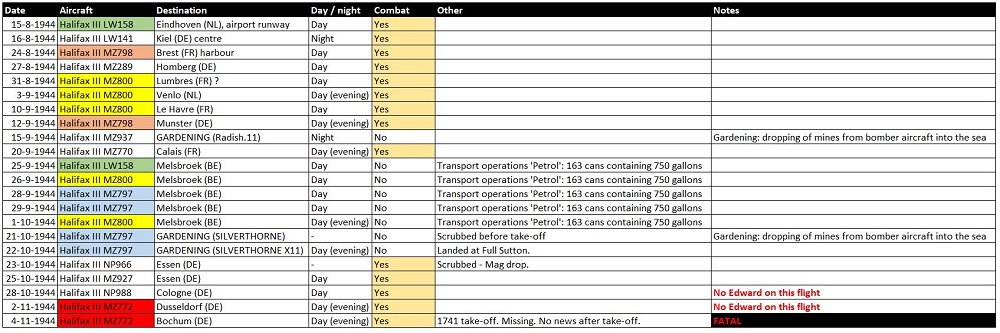

A month after joining the squadron, Edward experienced his first ‘combat flight’ as an Air Gunner, in the crew of Flight Officer A.C. Cameron. This daylight flight on August 15, 1944, in a Handley Page Halifax III with registration number LW158, attempted an attack on the runway at Fliegerhorst Eindhoven in the Netherlands. Edward was back in the Netherlands for a while anyway, if only briefly and in the air.

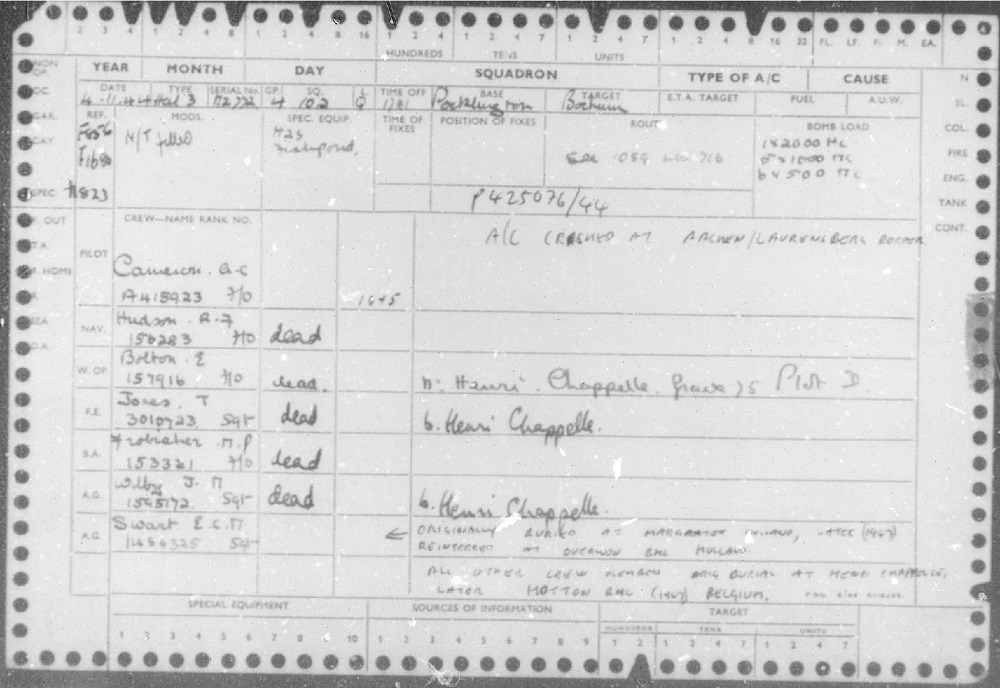

During the months August, September and October, Edward flew a total of twenty missions in various crews. He always flew Halifax IIIs, most often flying the MZ800 aircraft. He took part in day and night missions to targets in the Netherlands, Germany and France. Special flights included three planned ‘Gardening sorties’, where mines were to be laid in designated sea waters; two were carried out and one was cancelled before take-off. There were also five consecutive flights to Melsbroek Air Base, Belgium (B58 Melsbroek). These transport missions (operation ‘Petrol’) brought 750 gallons (about 2,800 litres) of fuel to the front each time.

Definitielijst

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Crash of the Halifax III MZ772

The fatal flight

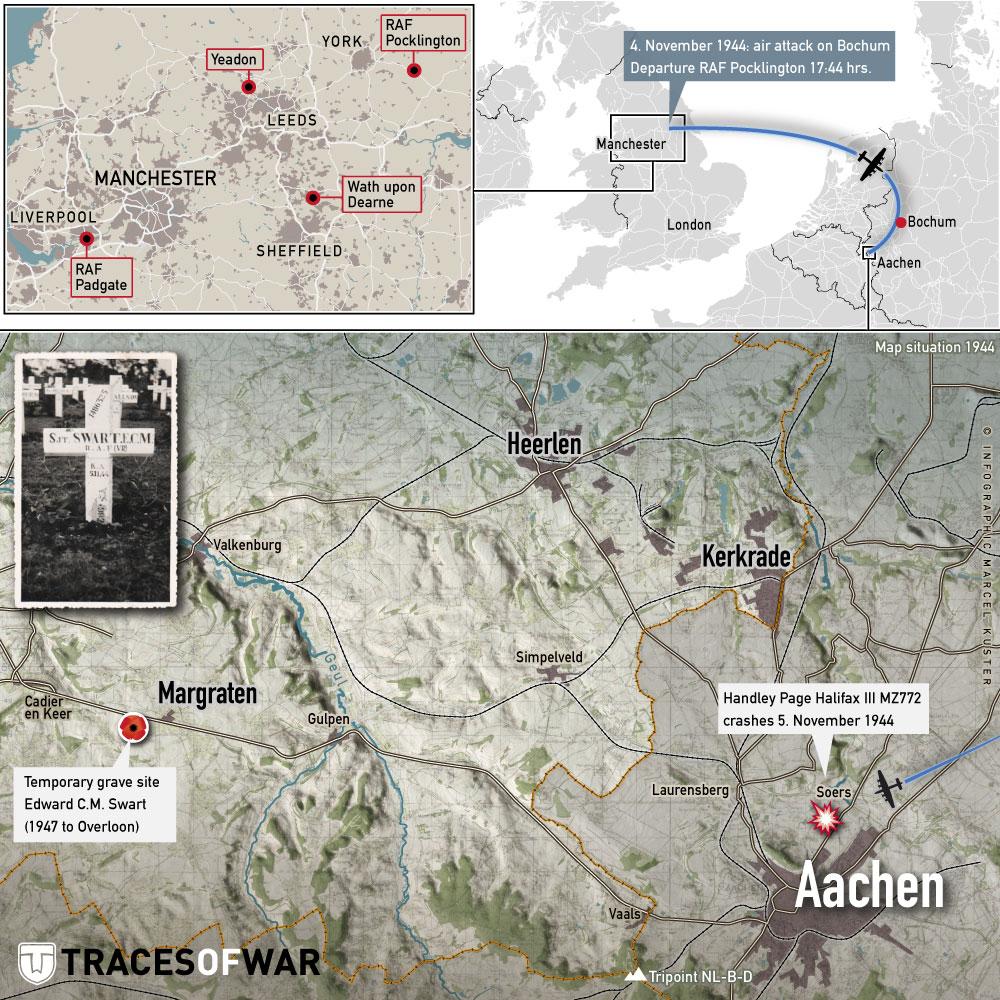

On November 2, 1944, Edward’s crew flew for the first time Halifax III MZ772 marked DY-Q on a mission to Düsseldorf. This aircraft had been used before, but not by this crew. It is also worth noting that Edward was not on this flight, but he was replaced by a Sergeant Wilson. On the previous flight Edward had been on leave on a mission to Cologne for an unknown reason. On the next flight Edward would return to the regular formation, but this would be his last. At 17:41 on November 4, 1944, the MZ772 left RAF Pocklington on a further night-time raid. In addition to Edward, the crew consisted of:

- Flying Officer Anthony Carlyle CAMERON (415923), Pilot

- Flying Officer Robert Frederick HUDSON (156283), Navigator

- Flying Officer Martin Peter FROBISHER (153321), Bomb Aimer

- Flying Officer Eric BOLTON (157916), Wireless Operator

- Sergeant Jack Madeley WILBY (1595172), Mid Upper Gunner

- Sergeant Thomas JONES (3010723), Flight Engineer.

Tonight’s destination: Bochum, Germany. A total of 749 aircraft took part in the raid, of which 28 were eventually lost (3.7%), mainly due to attacks by German night fighters.[8] It was a highly successful raid for the RAF, inflicting heavy damage on the centre of Bochum. Over 4,000 buildings were destroyed, including the steelworks. 994 people were killed. It was the last major raid on Bochum. The MZ772 with Edward on board crashed near Laurensberg, 4 kilometres north-west of Aachen, Germany, according to official records. The exact time and cause of the loss, according to the Aircraft Loss Card compiled by the Air Historical Branch after the war, have never been established. There is also no knowledge of whether the aircraft had been on its way to or from Bochum. Although Laurensberg was close by, the most likely crash site was the Soers. Two eyewitnesses are the most important primary sources.

Eyewitnesses

Local resident Hans Bücken Hans Bücken, born in 1935 and a native of the region, experienced the war at first-hand as a child. He knew of many crash sites, but not all. His notes include "Crash number 6 and 7", referring to Soers/Berensberg and Vetschau respectively. He came closest to these sites 2.5 miles from Aachen. Bücken describes the Soers crash site, near the old police headquarters, as follows: "The Soers is a district of the city of Aachen and lies roughly between Krefelder Straße and the Laurensberg district. Soerser Weg runs parallel to Krefelder Straße. These two streets are connected by Eulersweg. If you turn into Eulersweg from Krefelder Straße, Hubert-Wienen-Straße will be on your left after a few yards. This is the site of the old police headquarters. […] This area is now known as ‘Sportpark Soers’".[9]

Diary of local resident Antonia Jünger A second entry can be found in the diary of Antonia Jünger, who lived in Hasenwald in the former municipality Kohlscheid (now Herzogenrath). This hamlet lies halfway between Richterich and Rumpen on the Berensbergerstrasse. The woman kept a diary in two volumes from mid-1944 to May 1945. Under the entry for November 4, 1944, she wrote:

"Sehr viele Flugzeuge. 62 flogen direckt über den Hof. Die Erschütterung dauern an. Ein Am. Flugzeug zertrümmert in der Soers. Teile desselbigen flogen bis Holland."

Translation: "Many aircraft. 62 flew right over the yard. The shaking continues. An American aircraft crashed in the Soers. Parts of it flew to the Netherlands".

Eyewitnesses are otherwise rare in this investigation. This has to do with the fact that the crash site was on the front line of the war. Many civilians had sought refuge elsewhere.

Situation at the crash site

Dietmar Kottmann, president of the local history society ‘Laurensberger Heimatsfreunde’, wrote an historical article describing the chaotic conditions in the Laurensberg region during the final weeks of war. After the surrender of Aachen on October 23, 1944, the US Army found the city in disarray, with many buildings destroyed or badly damaged. Initially, all civilians remaining in Aachen were interned in a barracks in the south of the city and all German militaries were deported to prisoner of war camps in Belgium. Aachen continued to be shelled (including with V1s) from German positions to the east of the city. It is not known whether the Americans had noticed or documented any crashes during these days. Since about 90% of the population has been forcibly evacuated, it is possible that few people noticed the crash from a short distance on the night of November 4-5, 1944.

Timeline Aachen

- 12-09-1944: The First United States Army reached the German border at Aachen and aborted its advance due to lack of ammunition and fuel; operation Market Garden was given higher priority.

- Early October 1944: surrounding Aachen

- 23-10-1944: surrender of German troops defending Aachen

- November 1944: Aachen under US command

In 2022, there are no visible traces of this crash in the Soers region. An exact location has never been found and may never be found.

Seven graves, four burials

The ‘loss record’ of this flight tells us that the seven crew members were all found, presumably by the Americans, in the recently liberated area. There was probably no documentation of this on the US side due to the chaos. They were initially buried (as British) in an American cemetery, which reinforces the assumption that all crew member were recovered by the Americans at or near the crash site.

It is remarkable that all crew members, except Edward, were buried at the Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery and Memorial, while Edward was buried at the Netherlands American Cemetery and Memorial in Margraten. Subsequently, in 1947, all seven were reburied on their nearest Commonwealth War Cemetery. This is how the six finally ended up at Hotton War Cemetery in Belgium. Apparently, Edward and his other crew members were buried in Germany at different times and places, which may explain the two different burial sites.

Edward was eventually reburied at the Commonwealth War Cemetery on May 1, 1947. And so the story of a Briton with Dutch roots ended in a quiet, green cemetery in the Netherlands, where he remains to this day.

Notes

- Birth certificate Gijsbertus de Swart, to be consulted via Openarch.nl

- Civil registry community of Buren 1890-1899 (village of Buren), to be consulted via Regionaal Archief Rivierenland

- Civil registry community of Asperen: bl. 304-306 1890-1938, to be consulted via Regionaal Archief Rivierenland

- Civil registry Part 22, 1909 - 1921, wijk B (= continuation of part 19), archive number 0032, Archive of the community of Nieuwerkerk aan den IJssel, 1813-1928, inventary number 563, page 219. To be consulted via Samh.nl and Wiewaswie.nl

- Anecdote of the niece of Edward, Linda Woods-Sharples

- Notes Edward Henry Joel

- Springfield College

- Operations Record Book AIR-27-810-21

- E-mail contact with Hans Bücken 15 September 2022

Definitielijst

- Commonwealth

- Intergovernmental organisation of independent states in the former British Empire. A bomber crew could include an English pilot, a Welsh navigator, air gunners from Australia or New Zealand. There were also non-commonwealth Poles and Czechs in Bomber Command.

- Mid

- Military intelligence service.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

Information

- Article by:

- Lennard Bolijn-Verweijen

- Translated by:

- Lisanne Wehl

- Published on:

- 18-06-2023

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Sources

- Timenote.info - Edward Cornelius Martin Swart

- Air Forces WW2 Casualty : Sergeant E C M SWART (1486325), Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve [RAFCommands]

- Sergeant Edward Cornelius Martin Swart | War Casualty Details 1486325 | CWGC

- Edward Cornelius Martin Swart (1920 - 1944) - Genealogy

- SGLO Verliesregister

- Edward Cornelius Martin Swart's Family Tree

- Forces-war-records.co.uk: Edward Swart

- Rafcommands.com

- Forces-war-records.co.uk: Sergeant E.C.M. Swart

- Aireboroughhistoricalsociety.co.uk

- Chorley: Google Books

- Service number RAF Padgate

- UK National Archives

- UK National Archives: West Yorkshire Archive Service, Leeds, about empolyment at Edward Denison and Co.

- Tagesbuch Antonia Jünger, Heimatsverein Kohlscheid

- Laurensberger Heimatfreunde