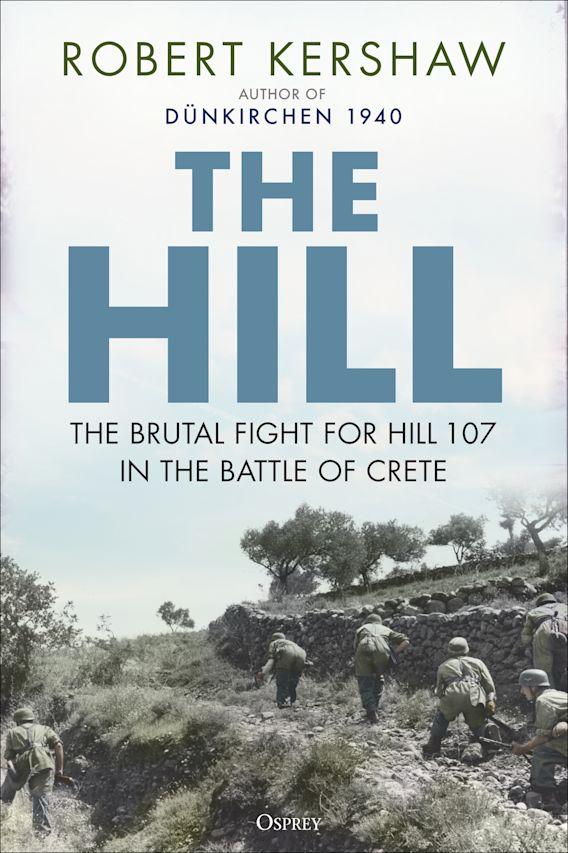

| Title: | The Hill - The brutal fight for Hill 107 in the Battle of Crete |

| Writer: | Kershaw, Robert |

| Published: | Osprey |

| Published in: | 2024 |

| Pages: | 368 |

| Language: | English |

| ISBN: | 9781472864550 |

| Review: | The conquest of the island of Crete in late May 1941 was a spectacular victory with a bitter aftertaste for the German air force. After nine days of fierce fighting, the Luftwaffe managed to bring this strategically located island in the Mediterranean Sea to its knees through heavy bombardments, paratrooper landings and glider assaults, but the losses incurred were disastrous. Particularly on the western side of the island, around the crucial airfield of Maleme and the nearby Hill 107, the Germans encountered fierce resistance from well-entrenched and determinedly fighting New Zealanders. Military historian Robert Kershaw has vividly reconstructed this three-day battle, utilizing both British and German sources. Crete, located between the Greek mainland, the coast of Libya, and the western part of Egypt, gained significant strategic importance after the German conquest of Greece in April 1941, with an eye on further German-Italian operations in Africa. The British were also aware of this. Following the retreat from Greece, New Zealand and Australian units settled on the island, joining the already present British garrison and Greek troops. On the eve of the German airborne landings, a total of about thirty thousand Allied soldiers were stationed on Crete, supplemented by around ten thousand Greeks. The defenders lacked sufficient tanks (there were only a handful of Crusader tanks) and artillery (what they had was mostly of Italian make), while the weakened Royal Air Force, with only about twenty aircraft, was no match for the Luftwaffe, which dominated the airspace around and above the island with nearly 300 bombers, 150 Stukas, and around 180 fighters. The motley collection of defending units was convinced the Germans would come, but there was enough time to dig cleverly chosen trenches and camouflage them well. It seems that the German preparation for the airborne landing on Crete was hindered by the simultaneously planned Operation Barbarossa - the invasion of the Soviet Union - which naturally took top priority in the allocation of resources and demanded much strategic attention from the high command. Additionally, earlier experiences with airborne landings in 1940 played a role. In a spectacular fashion, a small group of daring German paratroopers had managed to capture the strategically located Belgian fortress complex at Eben Emael, thus removing an important obstacle for the German tank advance towards France. This remarkable raid significantly boosted the already considerable self-confidence of Hermann Göring and his aviators, who believed their invincible Luftwaffe was suitable for any task. That was bravado. In reality, the large-scale airborne landings in the Netherlands could at best be called a partial German success, as the lightly armed and scattered paratrooper units that had landed around several airfields in South Holland could barely hold their own against Dutch counterattacks. Significant numbers of German paratroopers were taken prisoner. Additionally, the invasion of the Netherlands cost the Luftwaffe no fewer than 450 aircraft. Kershaw describes how the adventurous and ambitious Kurt Student, who was considered the founder of the paratrooper units (Fallschirmjäger) within the German army, took the initiative to visit Hitler and convince him of his plan to conquer Crete from the air. Student had at his disposal the XI Fliegerkorps, consisting of well-trained and motivated fighters who were to land directly on top of the Allied defensive lines using parachutes and gliders. The idea was to create panic among the defenders through bluff and surprise and to seize the initiative as attackers by not landing in one location and advancing from there, but by jumping simultaneously in multiple places and forming so-called 'oil spots' of units that remained in constant motion, thus preventing the formation of solid defensive lines. Logically, heavy weapons could not be carried by the Fallschirmjäger. This was not seen as an insurmountable problem, as the large number of Stuka dive bombers served as 'flying artillery,' while the island was heavily and systematically bombarded in the days leading up to the airborne landing. In his book The Hill, Robert Kershaw does not reconstruct the entire Battle of Crete, but focuses on the fighting in the northwestern part of the island, around the crucial airfield of Maleme and the strategically important Hill 107 opposite it. In the early morning of May 20, 1941, a German armada arrived, dropping at least three thousand bombs on the airfield and the hill in an hour and a half. Shortly thereafter, countless gliders full of soldiers began landing among the olive groves, while large numbers of paratroopers simultaneously jumped. The chaotic and deadly battle that ensued is vividly described by Kershaw, who constantly switches between the German and British (New Zealand) perspectives. The Battle of Crete lasted until June 1, when the last five thousand Allied defenders surrendered after more than fifteen thousand soldiers had been evacuated to Egypt. Kershaw's reconstruction makes it clear that the German conquest of Crete was a Pyrrhic victory. The lack of heavy weapons and faltering supply lines gave the landed German troops too little striking power, which could only be partially compensated for by the large air superiority. In total, the German forces deployed about 22,000 troops, of which an estimated more than five thousand were killed. These losses were so high that the role of the Fallschirmjäger was practically over after this. |

| Rating: |     Very good Very good |

Information

- Article by:

- Jan-Jaap van den Berg

- Published on:

- 04-07-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!