Introduction

Small State Diplomacy and Great Power Politics

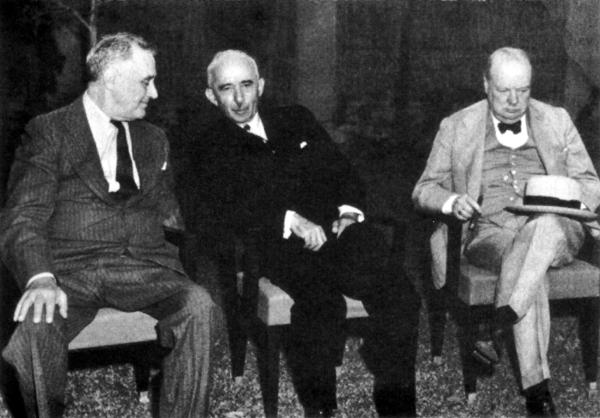

The Second Cairo Conference,[1] held in December 1943, was a critical diplomatic event where Turkish President Ismet Inönü met with President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The discussions focused on Turkey's potential entry into World War II on the side of the Allies. Ismet Inönü faced significant pressure from both Western leaders to join the war effort, primarily as a means to counteract Soviet influence in the region. The conference marked a shift in Turkish foreign policy from a primarily military-oriented strategy to one focused on political maneuvering and post-war positioning. Eventually, Turkey did join the Second World War symbolically in its dying months.

Franklin D. Roosevelt, Ismet Inönü and Winston Churchill at the Second Cairo Conference. Behind them their aides, including Anthony Eden. December 5, 1943. Source: United States Library of Congress

Regarding the subject matter and participants, the three Conferences (First Cairo, Tehran, and Second Cairo) were in part related and in part quite separate. The element of continuity running through all three meetings is to be found in the fact that President Franklin Roosevelt, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and their top advisers, including the Anglo-American Combined Chiefs of Staff, attended all three Conferences. The other principal participants, however, were different at each gathering. At the First Cairo Conference (November 22–26, 1943) the Anglo-American delegations conferred, in varying combinations, with Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek of China and his top military leaders on problems of the war against Japan. Then they flew to Tehran for four days of consultation (November 28–December 1, 1943) with Marshal Joseph Stalin, Foreign Commissar Vyacheslav Molotov, and Marshal Kliment Voroshilov on problems of the war in Europe. Back in Egypt for the Second Cairo Conference (December 2–7, 1943), they were joined by President Ismet Inonu of Turkey and other top Turkish officials for four days of talks about Turkey’s possible entry into the war against Germany.[2]

The Turkish tactics at Cairo, as they emerge from the records, interviews, and memoirs, were to conserve strength by remaining neutral for as long as possible, to obtain the maximum of armaments, and thus to prepare themselves for any eventuality posed by the Russians. They were prepared to go to war if the Allies insisted, but only if they supplied the necessary arms and, above all, sent a British or Anglo-American force into the Balkans.

Definitielijst

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

Turkey’s position during World War II at a glance

- Pasha, you left us hungry.

- Son, but I did not leave you fatherless.

Turkey's ability to maintain its neutrality for an extended period during World War II is undoubtedly the result of the bitter experiences it endured during World War I. In that war, the Ottoman Empire appeared to serve its own war objectives less and more to divert the firepower of Germany's enemies, thereby accelerating its own collapse. Therefore, the founding motto of the Republic of Turkey was "Peace at home, Peace in the World," and by striving to stay away from wars, the country aimed to accelerate its development. However, at the outbreak of World War II, Turkey prioritized defense expenditures, and throughout the war, the Turkish public faced poverty. During the height of the war, the Turkish government provided bread through rationing, ensuring everyone received the same amount. This poverty led to anger toward Ismet Inönü, who was one of the most significant figures and heroes of the Turkish War of Independence in the 1920s. After World War II, the opposition grew stronger, and only a few years later, an opposition party won the elections. After the war, an anecdote involving a small boy and Ismet Inönü during a public meeting was allegedly told. The boy shouted, "Pasha[3], you left us hungry," to which Inönü replied, "Son, but I did not leave you fatherless." This anecdote thoroughly describes the tensions between generations in Turkey during both wartime and post-war periods. It reflects Ismet Inönü's stance during the war and the hardships faced by the younger generation, who suffered from poverty while their fathers served in the military for almost four years, and who most likely voted against Inönü afterward.

Before World War II, in an effort to keep itself out of the war, Turkey signed several agreements: a Treaty of Friendship with Britain in April 1939, followed by a Tripartite Agreement with Britain and France in October 1939, and later a Treaty of Non-Aggression with Germany in June 1941. Balancing the interests of the warring parties was the very essence of maintaining neutrality.

During World War II, as Germany was stretching from Crimea to Rhodes, Turkey maintained diplomatic relations with Germany until August 1944. A German–Turkish Treaty of Friendship was signed on June 18, 1941, solidifying these ties. In October of the same year, the "Clodius Agreement," named after the German negotiator Dr. Carl August Clodius, was established. Under this agreement, Turkey agreed to export up to 45,000 tons of chromite ore to Germany between 1941 and 1942, and 90,000 tons annually in 1943 and 1944, in exchange for German military supplies. To counter this, the United States and the United Kingdom engaged in "preclusive buying," purchasing large quantities of Turkish chromite – even beyond their actual needs – to prevent its supply to Germany. Turkey's chromite ore was critical to Germany’s war effort, and its strategic neutrality and trade agreements significantly influenced the course of wartime economics and military capabilities.

During World War II, Turkey's strategic neutrality had a significant impact on the economic landscape of the Eastern Mediterranean. Although Hitler planned to invade Turkey after potentially defeating the Soviet Union, Turkey maintained neutrality to ensure regional peace and to facilitate crucial trade, particularly in chromite ore, which was vital for Germany's war economy. Chromite ore, which is essential for producing stainless steel and refractory bricks, was one of the few raw materials that Germany lacked adequate sources for within its own territory.

In 1938, world output of chrome ore was 1,125,000 tons per year, and the most important chrome producers before World War II were the Soviet Union, Turkey (neutral), Southern Rhodesia, the Union of South Africa, the Philippines, New Caledonia, Yugoslavia, Greece, and Cuba, with shares of world production of 19%, 19%, 16%, 16%, 6%, 5%, 4%, 4%, and 4%, respectively.[4] Considering that the Soviet Union consumed its entire production domestically, Turkey, Southern Rhodesia, and the Union of South Africa were the world’s leading chrome exporters. It is worth noting that, due to both the cost and risk of transporting chrome, and the fact that the producer countries were either allied powers or colonies of allied powers, Turkey was an indispensable source of chrome for Germany.

By early 1944, American experts estimated Germany’s chromite supplies at about 232,000 tons, with 46,000 tons coming from Turkey. The loss of these supplies was projected to be disastrous, potentially slashing German steel production from 35 million tons in 1943 to just 2 million tons per quarter by the end of 1944. This would also cripple the production of high-alloy steels and military ordnance, which would drop significantly.

Turkey's role was pivotal, as it was the only accessible source of chromite outside of occupied Europe by mid-1944. Despite an earlier agreement between Britain, France, and Turkey, which secured Turkish chromite for the Allies through 1942, the Clodius agreement allowed Germany to begin receiving Turkish chromite ore in January 1943. That year alone, Turkey exported more than 45,700 tons of chromite to Germany, effectively supplying most, if not exceeding, Germany's estimated annual requirement of 40,000 to 45,000 tons.[5]

Definitielijst

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- neutrality

- Impartiality, absence of decided views, the state of not supporting or helping either side in a conflict.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Invitation of conference

The President of Turkey, Ismet Inönü, was invited to Cairo through a letter personally written by U.S. President Frankli Roosevelt.[6] What is particularly interesting here is that Ismet Inönü would travel to Cairo aboard an American plane, escorted by both President Franklin Roosevelt's son-in-law and Prime Minister Winston Churchill's son.

President Ismet Inönü accepted the invitation "on condition that as between equals he is being invited to a free discussion and is not merely to be informed of decisions already arrived at in Tehran concerning Turkey." Another significant detail is that President Ismet Inönü; to avoid disrupting the balancing policy he had maintained with the Germans and to prevent giving the impression that military negotiations were taking place, brought no military advisors or bureaucrats with him. Of course, this had no practical consequence, as Ismet Inönü was a retired general and one of the leading commanders of the Turkish War of Independence. Thus, this situation exemplified a typical and pragmatic example of Turkey's nuanced diplomacy.

President Roosevelt to President Inönü[7]

Cairo, December 3, 1943.

My Dear President Inonu, I am sending one of my own planes to meet you and your party in Adana, together with my son-in-law, Major John Boettiger, who will hand this to you.

The plane is in command of Major Otis F. Bryan.

I hope you will have a smooth trip and I am looking forward with great pleasure to seeing you on Saturday afternoon.

Very sincerely yours,

F[RANKLIN] D R[OOSEVELT]

Conference Days

Just like a dialogue of the deaf

President Franklin Roosevelt of the United States and Prime Minister Winston Churchill of the United Kingdom, fresh from discussions at the Tehran Conference with Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, were poised to address the next strategic moves against the Axis powers. Turkish President Ismet Inönü arrived shortly after, bringing with him only a civil bureaucracy delegation keenly aware of the delicate position Turkey held between neutrality and active participation in the war.[8]

The daily meetings often commenced early in the morning and extended late into the evening, allowing for both formal negotiations and informal discussions over meals. The atmosphere was a blend of urgency and cautious optimism. Allied leaders were eager to secure Turkey's entry into the war to open a new front against Germany, while the Turkish delegation was measured, weighing the risks and benefits of abandoning their neutrality. Additionally, meetings were held not only with the leaders but also in detailed discussions between military officials regarding Operation Overlord (June 6 – August 30, 1944) and Operation Anvil - Later renamed "Dragoon’’ (August 15 – September 14, 1944).

The conversations were grounded in concerns over military resource allocation and aid, particularly the availability of landing craft for operations in the Mediterranean, which underscored many discussions. The President of the United States was particularly adamant that nothing should impede their primary operations—Overlord and Anvil—set to strike at the heart of German-occupied Europe. Even though Prime Minister Churchill was much more in favor of Turkey's entrance into the war, as was Stalin, though neither Stalin nor a Russian delegate attended the conference.

From the very beginning of the conference, Turkey’s Ismet Inönü and his delegation stated the lack of a concrete support plan and expressed concerns about Turkey’s preparedness. Winston Churchill promised at least 20 squadrons and indicated that the U.S. would contribute bombers, with additional tank needs being met via sea transport due to difficult rail access. With this proposal, the Allies were clearly pushing Turkey to decide to enter the war after six weeks of preparations. Ismet Inönü emphasized the necessity of a comprehensive defense plan before deciding on the timing of Turkey’s involvement, as well as the need for military specialists to come to Turkey for preparations, installations, and training so that Turkey could eventually be prepared to enter the war.

Ismet Inönü pointed out that the Allies were focused on other fronts and had not planned action in the Balkans. Winston Churchill confirmed this view but noted that, while the Turkish army was strong, attacking Turkey was not as straightforward as it seemed. The Soviet call for Turkey to join the war was significant, and Turkey was assured of support from Britain and the U.S. in joining the winning side. Ismet Inönü warned that the Germans had better-prepared Bulgarian forces than the Allies had prepared Turkey. Churchill indicated improvements in supplies since Adana. Prior to the conference in Cairo, on January 30, 1943, Churchill had secretly met with Inönü inside a train wagon to discuss Turkey joining the Allied powers and to arrange for the supply of RAF fighter squadrons and fully armored divisions to Turkey. After the meetings, dinners also showed that the atmosphere and informal gatherings were reportedly cordial but underscored by the high stakes of the negotiations. Winston Churchill was both persuasive and persistent, while Franklin Roosevelt adopted a more cautious approach, careful not to overcommit resources or promises. Ismet Inönü, a seasoned leader, navigated the pressures with prudence, seeking concrete assurances and mindful of his nation's preparedness.

A note from Admiral William D. Leahy very well described all discussions between all parties: "The next night, December 5, it was Churchill’s turn to entertain at dinner for Inönü. Same scene. Same cast. Almost the same lines, except that the Turkish President talked a little more freely and impressed me with his direct approach to the questions. He made it clear that before Turkey could come into the war, he would have to have enough planes, tanks, guns, etc., to make a strong resistance against invasion by the Nazis."

During a dinner with Franklin Roosevelt, Ismet Inönü reiterated his need for more substantial guarantees before abandoning neutrality, a sentiment that Roosevelt acknowledged, noting that if he were in Inönü’s place, he would demand more than the current assurances offered by Britain.

Thus, these debates in a vicious circle ultimately led to a stalemate, and, as a Turkish historian said, the conference was overall like a dialogue of the deaf.

At the end of the conference, this significant photo of the leaders from the conference shows their positions, as well as Winston Churchill's disappointed expression regarding the outcome.

Definitielijst

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- neutrality

- Impartiality, absence of decided views, the state of not supporting or helping either side in a conflict.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Between the lines from the conference

- By December 3, key discussions centered around Turkey's potential entry into World War II and its implications for Allied operations. President Franklin Roosevelt emphasized that nothing should impede Operation Overlord and Operation Anvil, which were the highest priorities.

He also stressed the need to secure sufficient landing craft for potential operations in the Eastern Mediterranean should Turkey join the war. - By December 4, the focus was on the strategic and political benefits of having Turkey enter the war, as well as the possible delays in this entry from December 31, 1943, to February 15, 1944. This delay was partly due to Russia’s stance on Romania's unconditional surrender. Agreements were summarized, stressing that neither Overlord nor Anvil operations should be hindered and that there should be adequate landing craft for the Eastern Mediterranean. Additionally, Admiral Mountbatten was to continue with his current resources. The Tripartite Meeting underscored the importance of Turkey joining the United Nations, with assurances from Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill that Russia would support Turkey if attacked. Winston Churchill proposed maintaining Turkish policy, supplying anti-aircraft materials, and positioning British and American combat squadrons, despite German protests and reactions from neighboring Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary. Roosevelt's dinner with Turkish President Ismet Inönü saw Winston Churchill pushing for Turkey to align with the Allies, while Franklin Roosevelt cautiously avoided making further promises of aid.

- On December 5, the issue of sending military resources to Turkey was a major concern, with fears that less critical operations might detract from the primary focus on Overlord and Anvil. During a second Tripartite Meeting, Ismet Inönü expressed skepticism about fixed dates for Turkey's entry and noted the absence of Russian representatives. In a separate meeting, Turkey showed tentative acceptance of the proposals but required assurances of adequate supplies, such as anti-aircraft guns and tanks, before committing to actions against Germany. Winston Churchill's dinner with Ismet Inönü continued the push for Turkey's commitment, with Winston Churchill's efforts being more forceful compared to the Americans' cautious urging.

- By December 7, the discussions revealed Ismet Inönü’s reservations about Turkey's preparedness and the need for essential supplies before committing to the war. He agreed to revisit Turkey's position after February 15, based on the status of preparations. Prime Minister Winston Churchill assurances included a guarantee that Bulgaria would not attack Turkey if Russia declared war. The next steps involved British experts visiting Ankara, Turkish generals meeting in Cairo for further talks, and ongoing diplomatic efforts from both the British and American sides.

After the second Cairo Conference

Even though Ismet Inönü reluctantly agreed, in principle, to enter the war on the condition of having a strong defensive system and adequate preparations, the military aid discussed throughout the conference was not provided to Turkey, and Turkey did not enter the war immediately following the conference. In response to increasing pressure in the following months, Turkey halted chromite shipments to Germany in April 1944. In June 1944, citing diplomatic reasons, Foreign Minister Menemencio?lu—who was known to be pro-German—was dismissed. By August 2, 1944, Turkey severed its relations with Berlin, officially shifting from a stance of benevolent neutrality towards the Allies to a pro-Allied position. With the Germans no longer posing a significant threat, Turkey declared war on Germany on February 23, 1945, and subsequently participated in the San Francisco Conference on April 25, 1945, alongside the Allies.

Strategies of the Countries

United KingdomWinston Churchill’s strategy aimed to utilize Turkey as a staging ground, employing air operations to weaken the German Balkan front. By establishing bases in Turkish airfields, the British could potentially capture the islands, enabling their fleet to reach the Dardanelles and drive German air forces out of the Aegean, thus disrupting enemy convoys. The British also sought to open a second front in the Balkans via Turkey in addition to the Italian invasion. Winston Churchill believed that merely preparing Turkey and allocating airfields was sufficient, without requiring additional land-based support.

United States of AmericaThe U.S. preferred a direct assault on Germany from Northern France rather than from the Mediterranean. Before the conference the US has a perspective that the timing for Turkey’s involvement in the war had not yet arrived, and continued sending arms and supplies to Turkey was planned. The U.S. had two main reasons for opposing Turkey’s entry into the war. Firstly, Ankara sought guarantees from Washington and London against Moscow, rather than Soviet aid, which could delay the invasion of France. Secondly, Turkey’s entry would negatively impact the Operation Overlord.

The Union of Soviet Socialist RepublicsThe Soviet Union’s foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov resisted Turkey’s early war entry, questioning the logic of supplying arms to a non-combatant nation and emphasizing that Turkey would need to endure hardship like Russia to be a part of the peace conference. First Deputy People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs of Soviet Union Andrey Vyshinsky also noted that Turkey’s entry would force Germany to withdraw 15 divisions from the Russian front and that Turkey needed to suffer during the war to be considered among the victors.

GermanyAdolf Hitler, whose strategy was focused on Russia, sought to maintain Turkey’s neutrality while ensuring that Greece fell under Axis control. In 1942, Berlin was reluctant to provide war materials to Turkey without receiving chromite ore in return. However, following the October 9, 1941, agreement and efforts by Ambassador to Turkey Franz Von Papen, an additional agreement was signed on May 30, 1942, allowing war material supplies in exchange for cotton, sunflower oil, and copper. Despite this, Turkey did not integrate this new agreement with the October 1941 deal and could only offer 45,000 tons of chromite for a tank division’s worth of materials in early 1943. Germany planned to take Eastern Thrace and the Dardanelles if Turkey entered the war, with operations scheduled for April 14, 1941. However, Franz Von Papen's efforts to prevent an attack on Turkish soil were not the primary reason for Germany's restraint; rather, Hitler's focus was on keeping Turkey neutral and only advancing into Greece. Instructions from February 27, 1941, indicated that German measures in the Balkans were directed against British forces in Greece, not Turkey. If Turkey considered this a cause for war, it was expected to state so clearly.

Republic of TurkeyAlthough Ismet Inönü agreed in principle to enter the war, he was determined not to commit Turkey without a strong defensive system and adequate preparations against potential attacks. Turkey's main position was to demand as much aid as possible for preparation, which in turn bought time and allowed Turkey to maintain its neutral position, avoiding the devastation of major cities like Istanbul and Izmir by the Luftwaffe and addressing concerns about Soviet objectives in the Balkans.

SECRET

[Cairo, 3 December 1943]

C. C. S. 418/1

ENTRY OF TURKEY INTO THE WAR

1. The object of this paper is to discuss the role that Turkey might be called upon to adopt if she agrees to come into the war, and the extent of our commitments likely to be involved.

TURKEY'S ROLE IN THE WAR

2. We consider that our object in the Balkans should be to bring about the surrender of Bulgaria and open a short sea route to Russia.

3. The surrender of Bulgaria is most likely to be achieved by:

a. Air action.

b. Russian diplomatic and subversive action.

c. The psychological effect of Turkey becoming an active ally of the United Nations.4. We do not propose that Allied forces should be concentrated in Thrace to cooperate with the Turks. In Thrace, therefore, the Turks must be persuaded to stand on the defensive and to concentrate their forces for the protection of the Straits. To assist them we would continue to bomb the Bulgarians.

5. The opening of a short supply route to Russia through the Dardanelles would achieve a considerable economy in shipping but might also enable us to take the strain off the Persian supply route. The Turks should be called upon to provide us with the bases from which to protect the convoys.

COMMITMENTS INVOLVED

6. The commitments which would be involved in the above policy can be considered under two headings:

a. Minimum air and anti-air assistance to the Turks, who make a great point of the necessity for protecting their main cities, communications and industries from German air attacks.

b. Action, within the capacity of the forces that can be made available, for opening the Aegean Sea, the capture of Rhodes and the other Dodecanese Islands.

Assistance to the Turks

7. We can provide a reasonable scale of air defense for Turkish key points.

Notes

- Edward Weisband, Turkish Foreign Policy, 1943-1945: Small State Diplomacy and Great Power Politics, Princeton University Press, 2015.

- history.state.gov

- Historical title of a Turkish officer of high rank.

- Murat Önsoy , The World War Two Allied Economic Warfare: The Case of Turkish Chrome Sales.

- Murat Önsoy, The World War Two Allied Economic Warfare: The Case of Turkish Chrome Sales.

- history.state.gov

- history.state.gov

- history.state.gov

Definitielijst

- division

- Military unit, usually consisting of one upto four regiments and usually making up a corps. In theory a division consists of 10,000 to 20,000 men.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- neutrality

- Impartiality, absence of decided views, the state of not supporting or helping either side in a conflict.

- second front

- During World War 2 the name of the front that the American and Brits would open in the West to relieve the first Russian front.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

Information

- Article by:

- M. Murat Can

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related books

Sources

- WEISBAND, E., Turkish Foreign Policy, 1943-1945, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2016.

- ÖNSOY, M., The World War Two Allied Economic Warfare, Vdm Verlag, Riga, 2009.

- Allied Relations and Negotiations with Turkey, US State Department.

- Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, The Conferences at Cairo and Tehran, 1943, Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute, United States Department of State.

- Keeping the Pot Boiling: British Propaganda in Neutral Turkey during the Second World War, University of Kent Blog.

- Panel on the 55th Anniversary of The Cairo Conference, 7th December 1998 Allied Relations and Negotiations with Turkey

- The Sextant, Eureka, and Second Cairo Conferences: November–December 1943 Papers And Minutes Of Meeting, The Joint History Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

- Overlord Versus the Mediterranean at the Cairo-Tehran Conferences, U.S. Army Center of Military History.

- Digital Archives of New York Times.

- The Austrian National Library, the Vienna edition of the Völkischer Beobachter.