Previous history

In August 1939 Hitler anticipated that the Allies would not come to Poland's aid if he could make them believe that Germany had fallen victim to Polish aggression. Prior to the start of "Fall Weiss", the invasion of Poland, several border incidents were staged by German commandos, disguised as Polish rebels. The most notable of these attacks was the Gleiwitz incident which occurred on the night of August 31-September 1.

The 111-metre-high transmitter mast, which remains to this day, the highest wooden building in Europe Source: Koos Winkelman.

The Gleiwitz radio station (today Gliwice) is nicknamed the 'Silesian Eiffel Tower' because of its shape. The radio tower is still in use and mainly draws tourists due to two special facts. First, it’s the tallest wooden construction in Europe. Second, it was here that an incident took place that Hitler used as a pretext to invade Poland. The Gleiwitz incident was an attack organised by the Nazis that had to appear as a Polish act of aggression.

After the armistice of November 11, 1918, and the signing of the Treaty of Versailles a year later, there was a lot of frustration in Germany about the compulsory ceding of territories. In the east, they lost West Prussia and Silesia to Poland. On top of that, the neighbouring Poland got a connection with the Baltic Sea, which separated East Prussia from the rest of Germany. Hitler was determined to overturn the so-called 'diktat’ of Versailles and get back the lost territories. After the Rhineland occupation (March 1936), the Anschluss (March 1938) and the annexation of Czechoslovakia (March 1939), he turned his attention to Poland. The plan was set for August 26. All Hitler needed in the summer of 1939 was a 'casus belli', a reason to start a war.

Definitielijst

- Anschluss

- The joining of Austria to Germany. The annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany on 12 March 1938. Austria became part of Greater Germany.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Rhineland

- German-speaking demilitarized area on the right bank of the Rhine which was occupied by Adolf Hitler in 1936 after World War 1.

Preparations

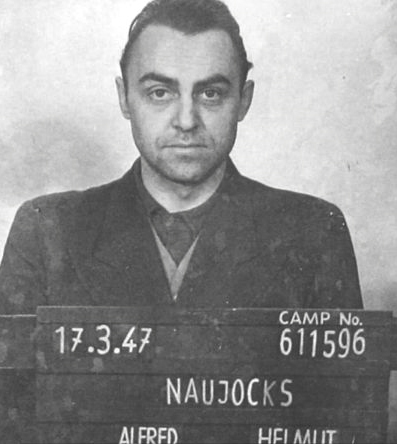

On August 10, preparations began. The order for the border incidents went from Hitler via Himmler to Heydrich. On the eve of Fall Weiss, actions of ‘Polish agression’ were to be carried out. During the night of August 25-26, Polish attacks on German territory had to be staged, at Hochlinden (today Rybnik-Stodoły), Pitschen (today Byczyna) and Gleiwitz respectively. At Hochlinden, a customs office was the target, at Pitschen a forestry station and at Gleiwitz, the radiostation. The action at Hochlinden was commanded by SS-Standartenführer Hans Trummler, at Pitschen, SS-Obersturmbannführer Otto Hellwig was in command. The man designated by Heydrich as responsible for Gleiwitz was Alfred Naujocks. Naujocks was born in 1911 in Kiel. When he was 20 years old, he enlisted in the SS. Naujocks, who posessed both wit and a good set of fists, quickly came to the attention of Reinhard Heydrich, who was in that period the head of the SD and SIPO. Heydrich saw in the young SS man the perfect man for his dirty jobs. Naujocks was in charge of a team of six SD men, mostly from Silesia. One of them was a radio-expert from Radio Berlin. The group received instructions and training at the Sicherheitsdienst-Schule Bernau for their future task. On August 12, three groups left for Hochlinden, Pitschen and Gleiwitz. The men stayed in local hotels, pretending to be business travellers. Naujocks’s group stayed in Haus Oberschlesiën. All three German locations were situated - in those days - in upper-Silesia, in the southeast of the German Reich, practically on the border with Poland.

Reinhard Heydrich, seated at his desk, with Alfred Naujocks. Picture from 1934. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 152-50-05 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

The fake attack at Hochlinden was to be carried out by ‘Polish attackers’ dressed in Polish uniform. The customs office was guarded by SS men in the uniform of the Grenzpolizei. Both groups had been extensively instructed. The ‘act’ was intended to draw the attention of Polish border troops, meaning to tempt them to enter German territory in order to demonstrate a military violation of the border. At Pitschen, ‘Polish insurgents’ would be deployed. These German soldiers grew their beards and moustaches in Polish fashion. They were assigned Räuberzivil (poor clothing) and carried Polish cigarettes, letters and cash. It was made clear that the use of radios was not allowed. The signal for the next phase of the action was to be passed on by Heydrich personally. The actions at Hochlinden and Pitschen were given the following code words: ‘Kleiner Auerhahn’ (little grouse) meant the signal for preparation, at ‘Grosser Auerhahn’ (big grouse), the actors were to go to their starting position. Only at ‘Agathe’, they were allowed to take action. For Naujocks and his mates at Gleiwitz the procedure was simpler. As soon as the message ‘Grossmutter gestorben’ (grandmother died) had been signalled to them, they had to take action immediately.

To demonstrate further the intention of the Polish aggression, Heydrich and SS- Oberführer Heinrich Müller - head of the Gestapo - came up with the idea of leaving the bodies of concentration camp prisoners at the Hochlinden crime scene. At KZ Sachsenhausen, random names were checked in the camp administration. These prisoners were taken to the Gestapo prison at Breslau and to the Gestapo headquarters at Prinz-Albrecht-strasse 8 in Berlin. On the eve of the actions they were to be delivered to Hochlinden and Gleiwitz, dressed in Polish uniforms and drugged. Müller went so far with this plan that he came up with a code name for these victims: ‘Konserve’ (canned food).

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Gestapo

- “Geheime Staatspolizei”. Secret state police, the secret police in the Third Reich.

- SIPO

- ”Sicherheitspolizei”. Combination (since 1936) of the Gestapo and criminal police.

Delay

On August 22, 1939, Hitler told his General Staff at Obersalzberg: ‘I will give an excuse for the outbreak of the war, credible or not. ‘The victor won’t be asked later whether or not he was telling the truth.’ The next day he gave the order to begin Fall Weiss on August 26 at 4:30 a.m. Heydrich immediately, sent orders to Hellwig, Trummler and Naujocks to get ready. On August 24, the German battleship Schleswig-Holstein sailed into Danzig harbour for a ceremonial visit. Several international newspapers carried pictures of the ship, dated 1906, proudly flying the Kriegsmarine flag. On the eve of the attack, Hitler got cold feet. At 8:30 p.m., he called off the attack indefinitely. Two events forced him to do this. Britain had promised Poland military support if the country was attacked by Germany. Also, Mussolini had told Hitler that he could not support Hitler in a general war: interventions in Ethiopia (1935-1936) and Spain (1936-1939) took a heavy toll on the Italian army. The Wehrmacht, Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine and most other units along the border were informed in time. However, there was a shooting incident with Polish troops near Mosty railway station, because the German commander could not be alerted in time.

Another group that did not receive the message in time was Otto Hellwig’s group, which was to take action at Hochlinden. Heydrich was furious and telegraphed: ‘Ihr seid wohl verrückt geworden!’ (‘You must have gone mad!’). From a local command post, a motorcycle orderly was sent after Hellwig’s men. The motorcycle orderly did not hesitate, but charged accross the border in German uniform and found the group about 200 metres further on, in Polish territory. They immediately retreated behind the border inconspicuously. Hellwig had mixed up two code words. He had not waited for ‘Agathe’ and had taken action at ‘Grosser Auerhahn’. Hellwig was unaware of any wrongdoing. On his return to German territory he ordered his troops to open fire on approaching Polish trucks. Only after a second warning did he realize the seriousness of his mistake. Back at the starting point, Trummler berated his collegue: ‘you made a big mess of it!’ Heydrich immediately relieved Hellwig of his command and appointed SS-sturmbannfüher Karl Hoffman as his replacement. Naujocks and his team were warned in good time, they did not even leave the hotel.

There was another matter that made Heydrich furious. At Chwalowice, a group of ethnic Germans had blown up a Polish customs office with hand grenades. After some investigation it became clear that this had not been the SD, but probably an Abwehr action. This time, Heydrich’s anger was directed at the head of the Abwehr, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. Heydrich suspected that Canaris could not stomach the fact that the Abwehr was not allowed to play a significant role in the secret operations prior to Fall Weiss. However, there was no evidence that Abwehr had anything to do with this coordinated attack.

Now that they had the chance to revise their plan, Heydrich and Müller decided to reduce the Hochlinden attack to a secondary component and to make the Gleiwitz operation the main event. The fact that no Polish corpse would be left at Gleiwitz did not sit well with Müller. He discussed the situation with Naujocks and he indicated that the victim should really be of Polish origin. After consulting the Gestapo archives, the name Franz Honiok emerged. Honiok was an ethnic German with Polish sympathies. A 43-year old bachelor Catholic farmer, he was arrested by the Gestapo in his hometown Hohenliebe. Honiok was drugged and the next day transported to Gleiwitz, where he was held in a police cell. It was to be his last night.

On the afternoon of August 31, Hitler decided not to wait any longer. He ordered to start Fall Weiss at 5:45 a.m. The OKW informed all commanders in the field. Heydrich phoned Trummler, Hoffman and Naujocks. At 16:00 pm, Naujocks – who had been locked up in the hotel – answered the phone and heard no more than ‘Grossmutter gestorben’ (grandmother died), Naujocks gathered his team and told them only then what was going on. Then, disguised as Polish workers, they got into two black cars and drove to the transmitter station, which was just outside the town's boundaries. The 8 Kw-transmitter of Gleiwitz was broadcasting on 1231 Khz, which allowed a (direct) range of up to 100 km during the day. As the D-layer of the ionosphere fell away during the night, all medium waves were reflected and the radio station could be received in London and Paris. That night, three people were on duty at the radio station: chief telegrapher Nawroth, techician Kot and night watchman Foitzik. In addition a Sicherheitspolizei man was present. Heydrich had ordered that other members of the police should be absent. It was a mild summer night and the two cars turned onto the stations’s grounds.

Definitielijst

- Abwehr

- Term used for the German military intelligence unit during the WW1 and WW2. From 1935 onwards under command of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. The organisation often came into conflict with other secret services such as the SD and the Gestapo. During World War 2 under Canaris frequently a source for conspiracies against the Nazi regime until in 1943 a major conspiracy by a number of prominent members of the Abwehr was discovered and the Abwehr was placed under command of Himmler. After the assassination attempt on Hitler in 1944, Canaris was discharged and the Abwehr was dissolved. The conspirators and Canaris were prosecuted and in 1945 they were executed atc oncentration camp Flossenburg.

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- OKW

- “Oberkommando der Wehrmacht”. German supreme command of the Armed Forces, Army, Air Force and Navy.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Implementation

Naujocks ordered two of his men to guard the front gate. The rest of the men entered the stone building armed. The first they encountered was watchman Foitzik. They grabbed him and slammed his head against the wall. Foitzik collapsed and was left bleeding on the floor. In the control room, Nawroth, Kotz and the Sicherheitspolizei, man were overpowered. With their hands tied, they were taken to the basement. Naujocks had one of his men guard the employees. From then on, things did not go well. The radio expert he had brought with him couldn’t get the transmitter working, and there was no microphone to be found. While the Berlin radio man fiddled with the controls, Naujocks and the others continued to search for a microphone. When they finally found one, the radio man had not made much progress. Naujocks decided to interrogate the prisoners. Nawroth was the only one who was familiar with the equipment. He said that voice transmissions were only possible via a telephone line to Radio Breslau. Nawroth's story did not go down well with Naujocks. The radio expert managed to get the transmitter working and Naujocks indicated that he could start broadcasting. The telephone rang unexpectedly and one of Naujocks men answered. Someone from Radio Breslau wanted to know what was going on. ‘Technical problems’, the robber shouted and put the receiver back on the hook. Naujocks didn't listen and pointed at the radio expert again, who grabbed the microphone and said loudly: "Uwaga! Tu Gliwice. Rozgłośnia znajduje się w rękach polskich." This text had been written shortly before. "Attention! This is Gliwice. The station is in Polish hands."

While the man made an inflammatory speech about Polish expansion, Naujocks and the others fired their guns into the ceiling. They shouted and made so much noise that it seemed as if a fight was going on. Franz Honiok was taken out of a car in drugged condition and dumped near the entrance to the building. There, one of Naujocks’ men shot him through the head. Naujocks ordered everyone to get into the cars and, satisfied with the way things had gone, he drove back to their hotel. It was some time before the prisoners discovered that their guard had disappeared. Kotz ran to the nearest house with his hands tied. Ten minutes later two policemen arrived on bicycles: the local police chief had heard the inflammatory speech on the radio and sent them out. At that moment a car arrived with Gestapo men in long leather coats. They knew about the incident and took over the general control of the situation. The Gestapo brought along a photographer to record the scene. The negatives were taken to the nearby airport, where Müller waited impatiently. He knew that civilian air traffic would be suspended a few hours before the start of Fall Weiss.

From the hotel Haus Oberschlesiën Naujocks called Berlin. He expected to receive a compliment from Heydrich. But the opposite happened. Angrily, Heydrich told him that he had listened to Gleiwitz, but had not heard anything of the transmission. Did Naujocks really deliver the message? It was only after the war that Naujocks realised there had been a major error in their plan. Gleiwitz was not a radio station with its own programme. It was merely a relay station, relaying the programme of Radio Breslau. The channel used by the radio expert was only used in emergencies such as floods or storms. When he cut the line with Breslau, people there became worried and picked up the phone to ask for information.

In the meantime, the action at Pitschen had also been completed. The forester's post had been looted and half a bucket of ox's blood poured out to give the impression of a massacre. As it was in the middle of nowhere, no ‘Konserve’ were left behind. In Hochlinden, Hoffmann and his group had attacked the customs post. The two Germans present lay on the ground in fear. Hoffmann ordered his men to smash everything to pieces and six concentration camp prisoners were lined up outside. When Hoffmann came out, they were all lying lifeless on the ground with head injuries. These ‘Konserve’ were wearing Polish uniforms. One of Hoffmann's men had a camera with a flashlight. He took some photographs, which were sent to Berlin by courier.

At 10:30 p.m., the first reports about the border incidents were broadcast on the German radio. Besides Gleiwitz, the provocations at Hochlinden and Pitschen were reported. Even the BBC briefly mentioned the attack on the Gleiwitz transmitter. The next morning at 10:00 a.m., Hitler began his speech at the Kroll Opera Haus. After the Reichstag fire of 1933, the German parliament had met in the Opera Haus opposite the Reichstag. ‘Tonight, for the first time, Polish troops have fired shots on our territory. Since 5:45 a.m., we have answered and bombs will be answered with bombs’. The Nazi dictator played the innocent victim. He happened to be wrong about the time, because the battleship Schleswig-Holstein fired the first shots at Fort Westenplatte in Danzig (Gdansk) at 4:47 a.m. Around the same time, Luftwaffe Stukas bombed the Polish town of Wielún. In his speech, Hitler did not refer to Gleiwitz, Hochlinden and Pitschen by name. Instead, he talked about border incidents, three of them serious.

As with other commando operations (Operation Greif and Operation Stösser), the impact was minimal, but the psychological aspect much greater than expected. Heydrich and Müller made the whole operation unnecessarily complicated. The radio message from Gleiwitz had only been received locally, at Hochlinden no Polish troops had been tempted to cross the border and the ambush at Pitschen had passed completely unobserved. The photographs of Honiok and the ‘Konserve’ were never used. When one of the policemen informed his family of his death, they were afraid to report his disappearance. Why then did Heydrich and Müller take all these precautions? It remains a guess, but it is suspected that in those days, a secret operation had to be planned with as much detail as possible. Even though it was pitch dark, the uniforms and clothing had to be as correct as possible. There were no manuals for this sort of things, so it was assumed that the operation should be carried out the way it happened in films and books.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Reichstag fire

- On the 27 February 1933 the building of the German government was set on fire. The Germans could declare a state of emergency and hereby come into power. It is not known whether the fire was started by the Nazi’s or the communists. The Dutchman Marinus van der Lubbe was in any case condemned for the crime.

After the war

The details of the Gleiwitz incident became known only after the war, during the Nuremberg trials. On December 20, 1945, Naujocks gave a written statement (see: Naujocks Statement). Alfred Naujocks was a man with an erratic war-record. Although Heydrich was furious about the failure of the radio broadcast, he ordered Naujocks to kidnap two British secret agents near Venlo on November 9, 1939. Walter Schellenberg was also involved in this action. In 1940, Naujocks was involved in an attempt to damage the British economy with counterfeit banknotes. The following year, Heydrich suddenly dropped Naujocks like a brick. Naujocks ended up on the Eastern Front, in Belgium and Denmark. He surrendered to American forces in November 1944. Naujocks was considered a petty criminal and was not convicted. In 1960, he published a book, together with the author Günther Pries with the resounding title ‘The Man who started the War’. The book was only published in Anglo-Saxon countries.

When the East German state film company DEFA made a feature film of the Gleiwitz Incident, Naujocks came back into the public eye. Der Spiegel, No. 46 in 1963, published an extensive interview with the leader of the Gleiwitz action. The Danes still wanted to try him for war crimes. But it was too late. In 1966, Naujocks died of heart failure. No documents about the Gleiwitz raid have survived. We have to rely on Naujocks' testimony (see: Naujocks Statement). There’s a good chance that the raid did not take place on August 31, but in mid-August. After the war, Naujocks changed the date (up to a few hours before the start of Fall Weiss), to enter history as the man who started the Second World War.

There's another strange thing connected with the Gleiwitz operation. It's usually referred to as the Gleiwitz Incident. As it happens, the operation is described by different names in different sources. In his book 'Kommando', James Lucas calls it Operation Hindenburg. The Osprey publication ‘Poland 1939’ (2002) refers to it as Operation Himmler and Wikipedia also uses this name. Dennis Whitehead and the German news magazine Focus, use the name Operation Tannenberg. During my research, I couldn't discover any logic in this. I suspect that this confusion is due to the lack of written documentation.

Definitielijst

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- Nuremberg trials

- Trials in 1946 of an allied military tribunal against the most important representatives of the Nazi regime. They stood trial as war criminals.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- war crimes

- Crimes committed in wartime. Often concerning crimes committed by soldiers against civilians.

Information

- Article by:

- Michiel Janzen

- Translated by:

- Cor Korpel

- Published on:

- 25-01-2025

- Last edit on:

- 31-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Sources

- LUCAS, J., Kommando, Arms & Armour Press, 1985.

- MOORHOUSE, R., First to Fight, Vintage Digital, 2019.

- Interview with former SS-Sturmbannführer Helmut Naujocks, Der Spiegel, nr. 46, 1963, on MythosElser.de (PDF).

- LEIPOLD, F., <'Alfred Naujocks: Der Mann der den Krieg begann', FOCUS Online, 15 November 2013, on: Focus.de

- WHITEHEAD, D., 'The Gleiwitz Incident', After the battle Magazine, nr. 142, March 2009. Thanks to Anne Palmer for her help in correcting the text.