Introduction

Within two weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt ordered a counterattack on Japanese soil itself. It was to become a daring raid by B-25 bombers, launched from an aircraft carrier. Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle was appointed to lead the mission, and the raid would therefore go down in history as the Doolittle Raid.

Definitielijst

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

Prologue

The Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, did not only shock the Americans. The tactically successful air attack on the American battleships anchored in Hawaii was also a moral blow to their allies, reinforced by a rapid succession of Japanese victories in the subsequent months. At an incredibly rapid pace, the Japanese conquered allied territory stretching from Burma, Singapore and the Dutch East Indies to islands in Polynesia. Just two weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor and to boost morale, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt instructed his Joint Chiefs of Staff, General George C. Marshall, General Henry H. Arnold, and Admiral Ernest J. King, to devise a way for the United States to launch an attack on Japan itself as quickly as possible. Although they themselves would prefer nothing else, an attack on Japan seemed impossible at that very moment.

It was Captain Francis S. Low, a submarine officer on Admiral King's staff, who suggested an air attack on Japan by US Army Air Force (USAAF) medium-range bombers that would be carried close enough to Japan by an aircraft carrier. King presented this idea to Captain Donald B. Duncan, his air operations officer. Duncan then studied different types of bombers that were used by the Americans at that time. According to him, the Douglas B-18 Bolo was out of the question because the aircraft's 500-kilometer range was too limited. The Douglas B-23 Dragon was not eligible because it had too large a wingspan to be launched from an aircraft carrier. The Martin B-26 Marauder could not be deployed because this aircraft required too long a runway. According to Duncan, the North American B-25 Mitchell theoretically met the requirements for such a mission.

General Arnold in particular was enthusiastic about this concept, and he summoned Lieutenant Colonel James Harold Doolittle, an experienced US Army pilot and flight instructor in World War I and a test pilot in the 1930s. He had returned to military service on July 1, 1940, and was assigned to Arnold's staff in Washington DC. Doolittle was tasked to find out which USAAF aircraft would be suitable to take off with a bomb load of 900 kilograms from a runway that was no longer than 142 meters and no wider than 25 meters. Also, the aircraft had to have a range of almost 2,500 nautical miles. The former test pilot investigated the possibilities of the same aircraft as Duncan had done and came to the same conclusion. The B-25 Mitchell could do it, provided the aircraft was equipped with extra fuel tanks. Only then, Arnold informed Doolittle on the true purpose of the investigation and the latter volunteered to lead the mission. Arnold accepted his offer and promised Doolittle full cooperation.

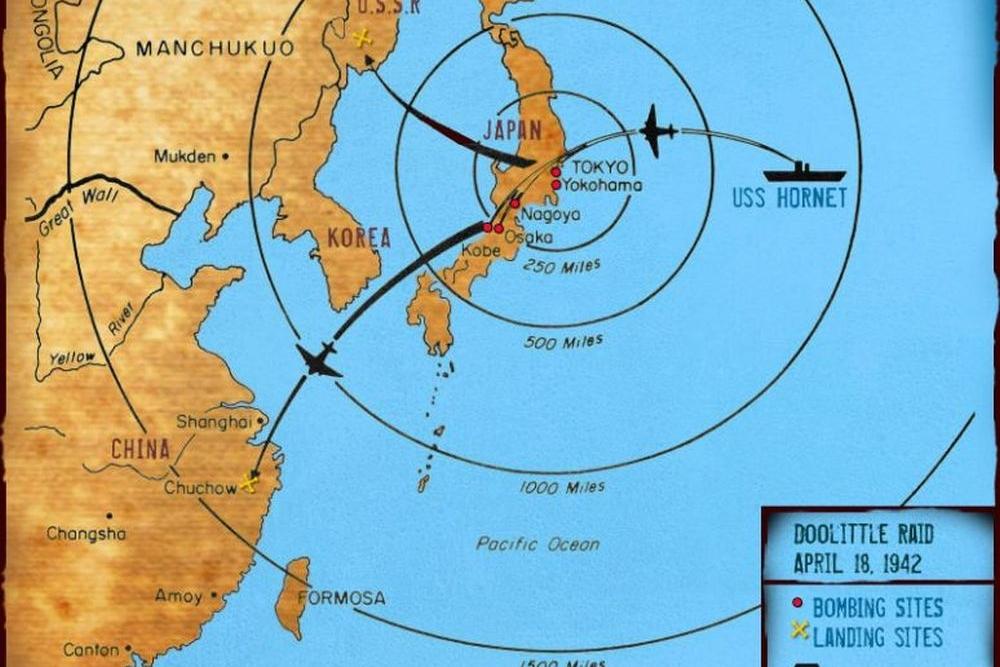

The concept of the daring American raid on Japan in early 1942 was as follows: a naval task force would transfer fifteen B-25 Mitchells to a location 450 nautical miles off the coast of Japan from where the aircraft would take off from an aircraft carrier and bomb targets in Japan. The aircraft would then continue fly to China where they were to be incorporated in the American Tenth Air Force that was being established at that time and had been assigned the China-Burma-India combat area. Because the mission had to remain secret, Doolittle was not allowed to inform anyone about the true facts of the mission, not even during the preparations.

Doolittle and crew (from left to right): Lt. Henry A. Potter, observer; Doolittle, pilot; S.Sgt. Fred A. Braemer, bomb aimer; Lt. Richard E. Cole, co-pilot; S.Sgt. Paul J. Leonard, flight engineer/gunner, USS Hornet (CV-8), April 18, 1942. Source: US Army Air Force - 060217-F-1234P-117

About the importance of the mission, Doolittle later wrote in his autobiography:

“The Japanese had been told they were invulnerable. An attack on the Japanese homeland would cause confusion in the minds of the Japanese people and sow doubt about the reliability of their leaders. There was a second, equally important, psychological reason for this attack … Americans badly needed a morale boost.”

Definitielijst

- moral

- The will of the troops/civilians to keep fighting.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

Preparations

On February 2, 1942, two B-25 Mitchell bombers were lifted aboard the new Yorktown-class aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8) at Norfolk Naval Base, Virginia. That same day, both B-25 aircraft were successfully launched from the aircraft carrier, which was located several miles off the east coast of the United States. The Hornet was then directed to the American east coast for her first war duties. Doolittle had meanwhile decided that the crews of the Mitchells would each consist of a pilot with overall command, a co-pilot, a navigator, a bomb aimer and a flight engineer/gunner. A total of 24 B-25 Mitchells and their crews were assigned to the mission. They came from three squadrons of the 17th Bomb Group and the associated 89th Reconnaissance Squadron from USAAF base Pendleton, Oregon. To maintain secrecy, Doolittle personally prepared as much as possible for the training, parts and equipment he would need, without explaining to anyone.

B-25B of the 34th Bombardment Squadron on Mid-Continent Airlines, Minneapolis, Minnesota, January - February 1942. Source: US Army Air Force photo

The four squadrons of B-25 Mitchells from Oregon were equipped in Minneapolis, Minnesota, with additional fuel tanks, fuel lines, modified bomb racks and film cameras that would be electronically activated when the bombs were dropped over Japan. The 24 aircraft were then flown to Columbia, South Carolina, where the air crews were asked if they would voluntarily participate in a "dangerous mission". Almost all men of the four squadrons volunteered for the very dangerous, but still secret assignment. The volunteers were sent with their aircraft to Eglin Field in Florida where they started their training. Doolittle himself arrived at the American air base near Pensacola in northwest Florida on March 3, 1942. He gathered the 140 volunteers, including a small number of weapons specialists and mechanics, and addressed them:

"My name`s Doolittle. I`ve been put in charge of the project you men have volunteered for. It`s a tough one and it will be the most dangerous thing any of you have ever done. Anyone can drop out and nothing will ever be said about it."

He then reminded the men that the mission was and must remain highly secret:

"This entire mission must be kept top-secret. I not only don't want you to tell your wives or buddies about it; I don't even want you to discuss it among yourselves."

Although only fifteen B-25 Mitchells were to be deployed, all 24 crews underwent the same training supervised by Lieutenant Henry L. Miller of the US Navy. The remaining crews would act as reserves. They were trained to take off from an extremely short runway, to navigate at extremely low altitudes and to target bombs. Gradually, the Mitchells were stripped of all parts that could be spared to reduce weight. The modern Norden bombsight was removed because it was not considered to be of much use at low altitude, but also to prevent the still secret instrument from falling into Japanese hands. It was replaced by a simple but effective device consisting of two pieces of aluminium. Furthermore, the two .50 machine guns were removed from the tail turret and replaced with black-painted broomsticks to fool any enemy fighter pilots. The lower gun turret and the lightly armoured plates from the nose were completely removed.

During the training, one of the pilots dropped out due to illness and Doolittle decided to take his place. The crew of his bomber would from then on consist of co-pilot Lieutenant Richard E. Cole, navigator Lieutenant Henry A. Potter, bombardier Sergeant Fred A. Braemer and engineer/gunner Sergeant Paul J. Leonard.

Meanwhile, Captain Duncan had travelled to Hawaii where he met with the Commander in Chief of the US Pacific Fleet, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz. Nimitz approved the plan for the Doolittle Raid and assigned Admiral William F. Halsey to lead the Navy Task Force for the raid. Duncan then further developed the plans with Nimitz's staff where it was decided that the Task Force should consist of sixteen warships, including two aircraft carriers. Seven ships were to escort the Hornet from Alameda Naval Air Station near San Francisco and rendezvous at the 180th parallel with a task force consisting of Halsey's flagship, the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise, and seven escort ships. In mid-March, USS Hornet (CV-8) transited the Panama Canal and headed for Alameda. Duncan signalled to Washington DC: "tell Jimmy to get on his horse". This code message meant that Doolittle had to fly his B-25 Mitchells to the west coast. Two of the bombers had been damaged during training, so that by the end of March 22 aircraft arrived at McClellan Field near Sacramento, California, for a final inspection. A few days later, sixteen of the B-15 Mitchells, their crews and the weapons specialists and technicians from the Doolittle group were transferred to the Hornet.

On April 2, 1942, Task Force 16.2 departed from San Francisco and consisted of the aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8), the heavy cruiser USS Vincennes (CA-44), the light cruiser USS Nashville (CL-43), the oiler USS Cimarron (AO-22) and the destroyers USS Gwin (DD-433), USS Meredith (DD-434), USS Monssen (DD-436) and USS Grayson (DD-435). Five days later, Task Force 16.1 departed from Hawaii. This task force consisted of the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6), the heavy cruisers USS Northampton (CA-26) and USS Salt Lake City (CA-25), the oiler USS Sabine (AO-25), and the destroyers USS Balch (DD-363), USS Benham (DD-397), USS Ellet (DD-398), and USS Fanning (DD-385). On April 12, 1942, the two task forces joined one another en route to Japan and formed Task Force 16 under Admiral Halsey. Both Halsey and Doolittle were acutely aware that Task Force 16 was at particular risk. If the sixteen ships were discovered prematurely and had to engage Japanese warships, the 16 B-25 Mitchell bombers fastened on the flight deck of USS Hornet would have to be pushed overboard to clear the deck for the carrier's fighter planes. Any submarine danger would have to be averted by the eight destroyers. Also, the Americans risked the loss of two particularly valuable aircraft carriers. All in all, Task Force 16 was particularly vulnerable at this stage of the war with Japan.

Definitielijst

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- Raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

The Raid

En route to Japan, Doolittle briefed his raiders on the objective. The bomber crews responded enthusiastically and were prepared to endure all the dangers of the mission. Doolittle told them the plan was to sail within 480 nautical miles of Japan and then take off from the Hornet late in the afternoon. The first bombers would reach Tokyo under cover of darkness and drop mainly incendiary bombs. The burning targets would then provide a beacon for the next series of bombers that were assigned targets in Tokyo, Yokohama, Yokosuka, Nagoya, Osaka and Kobe. The B-25 Mitchells would each drop a total of four 500-pound bombs. By virtue of the additional fuel tanks, the fuel supply was expanded from more than 2,600 litres to 4,300 litres and should be sufficient to reach mainland China after the raid had been completed.

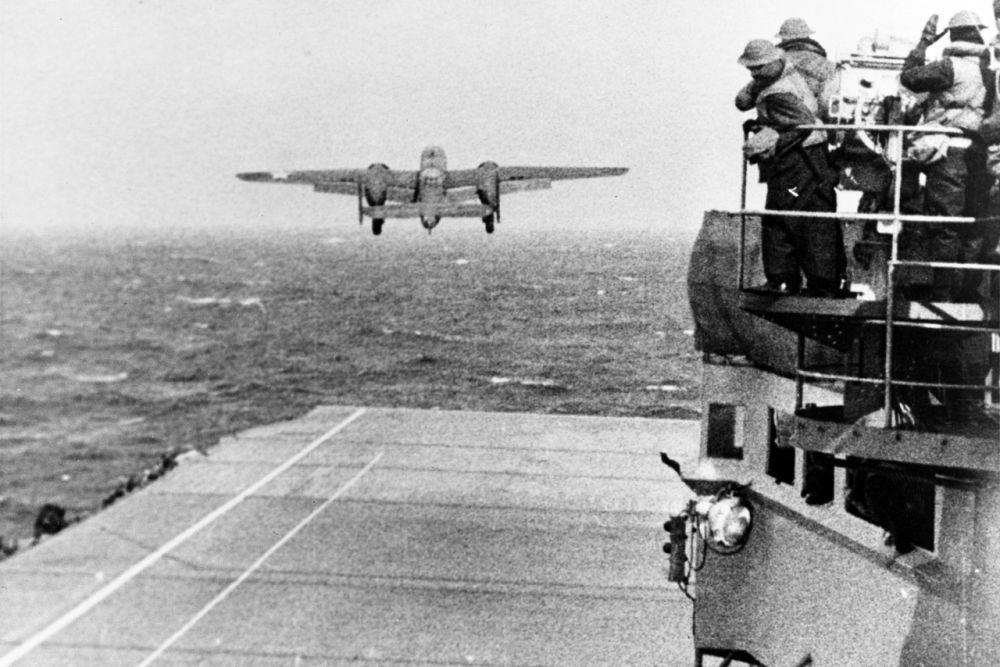

On April 17, 1942, the warships were replenished with oil from the tankers, which then returned to their home bases, escorted by several destroyers. The next morning, April 18, at 0738 hrs, a small vessel was sighted on USS Enterprise's radar and a reconnaissance aircraft was launched. The pilot spotted a Japanese patrol boat and signalled to the Enterprise: “believed seen by enemy”. This message set off a chain reaction on board the American ships. Admiral Halsey signalled to the Hornet that the B-25 Mitchell bombers were to be launched immediately. The cruiser USS Nashville attacked the Japanese patrol boat No. 23 Nitto Maru, a converted fishing trawler, and fatally damaged the vessel. The Japanese had been warned but expected the type of aircraft with a relatively short range that were usually launched from aircraft carriers. Their counteractions therefore started too late. At 0820 hrs, Doolittle was the first to take off from the Hornet's 450-foot flight deck. Less than an hour later, the sixteenth bomber, which had been taken as a reserve but had been equipped at the last minute by order of Doolittle to be part of the raid, took off from the American aircraft carrier. All B-25 Mitchell bombers went airborne safely, albeit 10 hours and more than 170 nautical miles early. Doolittle knew all too well that the longer distance would make it very hard to reach China.

Doolittle takes off with his aircraft from USS Hornet. Source: US Air Force photo 420418-F-0000D-003

Overview of the 16 B-25 Mitchell bombers in order of take-off from USS Hornet:

| USAAF serial nr | Squadron | Target | Pilot | Location of emergency or crash landing |

| 40-2344 | 34th Bombing Sq. | Tokyo | Lieutenant Colonel James H. Doolittle | Crashed Quzhou, China |

| 40-2292 | 37th Bombing Sq. | Tokyo | Lieutenant Travis Hoover | Emergency landing Ningbo, China |

| 40-2270 | 95th Bombing Sq. | Tokyo | Lieutenant Robert M. Gray | Crashed Quzhou, China |

| 40-2282 | 95th Bombing Sq. | Tokyo | Lieutenant Everett W. Holstrom | Crashed Shangrao, China |

| 40-2283 | 95th Bombing Sq. | Tokyo | Captain David M. Jones | Crashed Quzhou, China |

| 40-2298 | 95th Bombing Sq. | Tokyo | Lieutenant Dean E. Hallmark | Emergency landing on sea near Wenzhou, China |

| 40-2261 | 95th Bombing Sq. | Tokyo | Lieutenant Ted W. Lawson | Emergency landing on sea near Changshu, China |

| 40-2242 | 95th Bombing Sq. | Tokyo | Captain Edward J. York | Emergency landing 65 km south of Vladivostok |

| 40-2303 | 34th Bombing Sq. | Tokyo | Lieutenant Harold F. Watson | Crashed Nanchang, China |

| 40-2250 | 89th Reconnaissance Sq. | Tokyo | Lieutenant Richard O. Joyce | Crashed Quzhou, China |

| 40-2249 | 89th Reconnaissance Sq. | Yokohama | Captain C. Ross Greening | Crashed Quzhou, China |

| 40-2278 | 37th Bombing Sq. | Yokohama | Lieutenant William M. Bower | Crashed Quzhou, China |

| 40-2247 | 37th Bombing Sq. | Yokosuka | Lieutenant Edgar E. McElroy | Crashed Nanchang, China |

| 40-2297 | 89th Reconnaissance Sq. | Nagoya | Major John A. Hilger | Creashed Shangrao, China |

| 40-2267 | 89th Reconnaissance Sq. | Kobe | Lieutenant Donald G. Smith | Emergency landing on sea near Changshu, China |

| 40-2268 | 34th Bombing Sq. | Osaka | Lieutenant William G. Farrow | Crashed Ningbo, China |

Around noon, the out-of-formation and low-flying B-25 Mitchell bombers reached Japan and almost all successfully dropped their bombs on the assigned targets. However, Lieutenant Holstrom's plane was attacked by Japanese fighter planes and had to drop its bomb load in Tokyo Bay. Several other Mitchell bombers were also attacked by enemy aircraft, but none suffered fatal damage. The targets in the various Japanese cities consisted of weapons factories, shipyards and other military and industrial objectives. After the bombing, fifteen of the bombers turned southwest, towards China. Captain York's B-25 had consumed more fuel than the other bombers due to a mechanical defect and had to divert to the Soviet Union. He hoped that the Soviets could be persuaded to supply the plane with fuel so that it could still divert to China and landed the bomber 40 miles below Vladivostok. However, the Soviets wanted to maintain their neutrality towards Japan and were therefore felt compelled to seize the B-25 and the crew was interned.

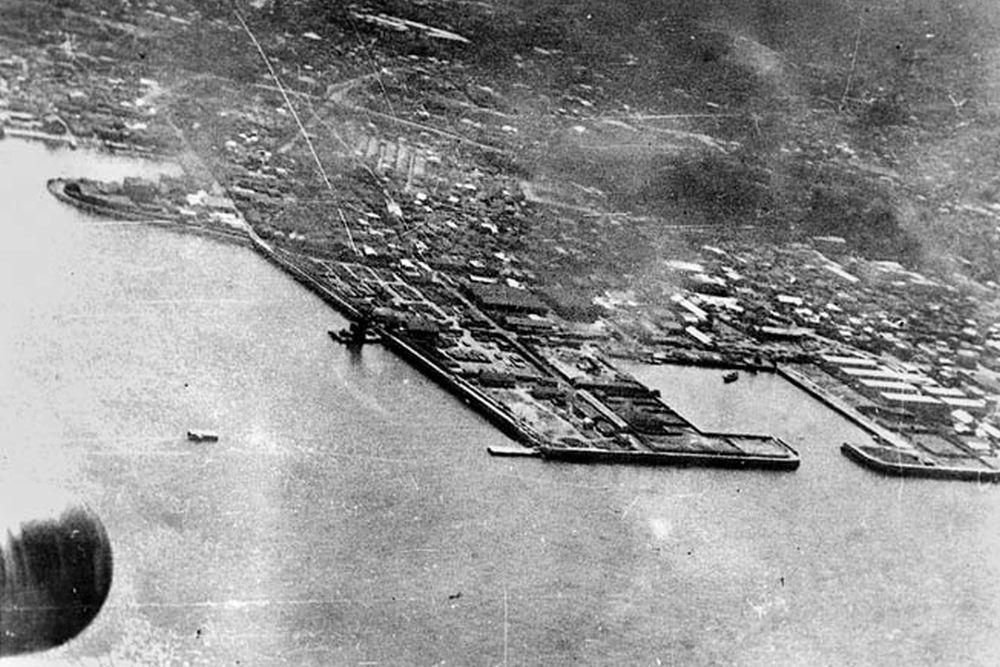

Yokosuka naval base near Tokyo seen from most likely aircraft 13, Lieutenant Edgar E. McElroy. Source: US Air Force photo

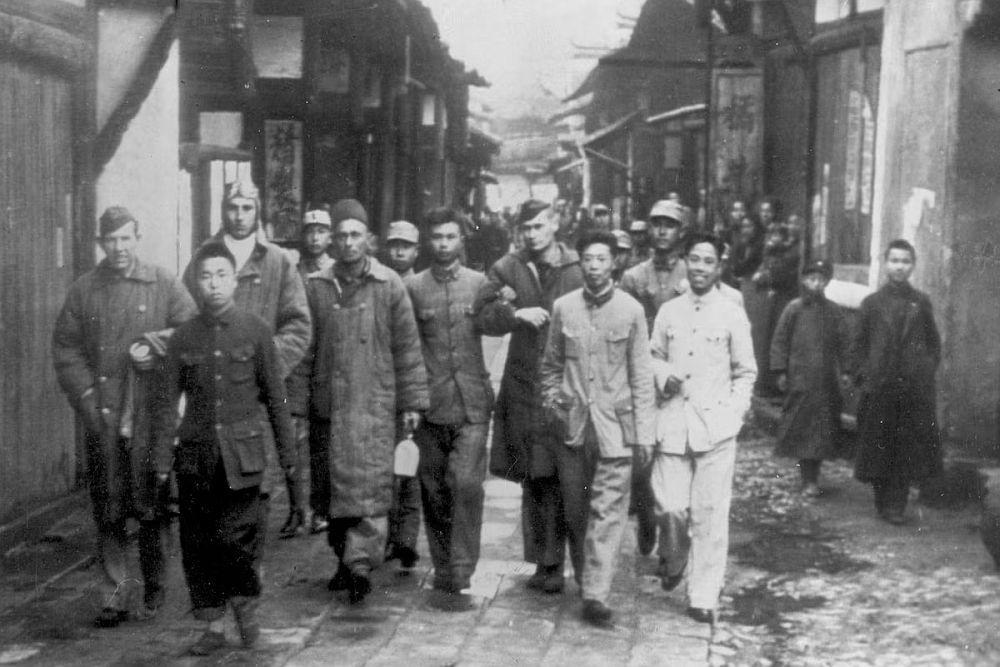

The fifteen bombers on their way to China were helped at the last minute by a northeasterly wind that drifted the planes into the right direction. Doolittle and 10 other captains bailed the crews out of the planes after they arrived over mainland China. Corporal Faktor, who was part of the crew of Lieutenant Gray's aircraft, was killed in his bailout attempt. The remaining four pilots chose to make an emergency landing of their B-25 Mitchell off the Chinese coast or on land. Two crew members drowned while attempting to swim to shore. Four seriously injured raiders were taken by Chinese farmers to a missionary-run hospital. Doolittle and the other raiders, who had landed safely, were assisted by Chinese soldiers and civilians to reach unoccupied Chinese territory. Ultimately, 64 of them managed to reach Chongqing where they were out of reach of the Japanese. Eight crew members were captured by Japanese forces before they could be rescued.

Definitielijst

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- neutrality

- Impartiality, absence of decided views, the state of not supporting or helping either side in a conflict.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Direct and Indirect Consequences

To find the American pilots and other crew members, the Japanese launched the so-called Zhejiang-Jiangxi campaign, named after the two Chinese provinces which had been occupied by Japan since Second Sino-Japanese War had started in 1937. The Japanese acted ruthlessly. Chinese citizens were tortured to obtain information and murdered as a deterrence and even biological weapons were used to kill villagers in revenge for aid to the Americans. The Japanese army also evacuated and disabled all possible airfields and areas that could be used by Allied aircraft to carry out bombing flights against the Japanese homeland. Here as well, the local population was not spared either. In their search for the Doolittle Raiders, the Japanese would kill around 250,000 Chinese in revenge attacks and during forced evacuations.

The damage inflicted on the Japanese cities by the sixteen B-25 Mitchell bombers was extremely limited. The Japanese dismissed the Doolittle Raid in April 1942 as the Do-Nothing Raid, but at the same time the violent Zhejiang-Jiangxi campaign proved that their pride had been deeply hurt. Notably the fact that the Japanese armed forces had been unable to repel the attack and thus protect the emperor weighed particularly heavily on them.

The success of the Doolittle Raid also had a strategic impact. For example, Admiral Chuichi Nagumo's fast aircraft carrier squadron, which had led the attack on Pearl Harbor and had successfully attacked and sunk Allied warships in the Indian Ocean in the months that followed, was recalled to Japanese waters to defend the homeland. This was an enormous relief for the mainly British, but also Dutch, Australian and American naval fleets in that area. Furthermore, four aircraft fighter groups were kept stationed in Japan even though they were urgently needed in the Pacific War.

The most important strategic consequence of the Doolittle Raid, however, was the final decision by the Japanese High Command to continue with the plan to attack the Midway Islands and the Aleutian Islands, and even to advance it. The Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, had advocated expanding and strengthening the defensive belt around Japan by occupying the Midway Islands, west of Hawaii, and the Aleutian Islands, a string of islands southwest of Alaska. He also wanted to draw out the American aircraft carriers during this mission and defeat them in a final battle. The Navy General Staff, led by Admiral Osami Nagano, wanted to isolate Australia by occupying Fiji, New Caledonia and Samoa. The army leadership would prefer to advance into China to conquer as much territory as possible. The successful Doolittle Raid showed all Japanese leaders that Yamamoto was right. Therefore, the conquest of Midway and the Aleutians was approved and even moved forward on the agenda. The Battle of Midway, which would result from these plans, would have disastrous consequences for the Japanese navy. Due to a combination of circumstances and because the Americans had managed to break the secret radio codes of the Japanese, the Americans managed to sink four Japanese aircraft carriers thereby losing only one of their own. Japan could not replace these capital ships and their aircraft and pilots, which made the Battle of Midway the tipping point in the Pacific War. From that moment on the Japanese victories came to an end.

The damage, while materially limited, was mainly psychological. Source: National Institute for Defense Studies (Japan)

The most immediate consequence of the Doolittle Raid was purely psychological. The quick victory gave the Americans an enormous morale boost, while the buzz of victory enjoyed by the Japanese armed forces was abruptly broken and the Japanese people's confidence in those same armed forces was harmed. Also, anti-Japanese sentiments among the Allies were further fuelled by the news of the Japanese army's massacre of the population in the Chinese provinces of Zhejiang and Jiangxi.

Definitielijst

- Midway

- Island in the Pacific where from 4 to 6 June 1942 a battle was fought between Japan and the United States. The battle of Midway was a turning point in the war in the Pacific resulting in a heavy defeat for the Japanese.

- Raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Epilogue

After many wanderings, a total of 64 Doolittle Raiders arrived in the city of Chungking, currently spelled as Chongqing, and located in unoccupied Chinese territory. Most of them would continue to fly many missions for the Allies, some as part of the Tenth Air Force in Southeast Asia and some in Europe. Thirteen of them would die during combat missions during the Second World War.

On August 15, 1942, the United States was informed by the Swiss consulate in Shanghai of the fate of the missing ten crew members of the B-25 Mitchell bombers that had taken off sixth and last. Two of them, Sergeant Dieter and Corporal Fitzmaurice, had drowned and eight had been arrested by Japanese troops and imprisoned in Japanese police headquarters in Shanghai. On October 19 of the same year, the Japanese announced that the eight had been sentenced to death, but that some of them would have their sentences commuted to life imprisonment.

Sgt. Harold Spatz (flight engineer/gunner aircraft 16), Lt. Dean Hallmark (pilot aircraft 6) and Lt. William Farrow (pilot aircraft 16), during their execution at the Shanghai General Cemetery, 1942. Source: Public Domain (unknown)

It was not until February 1946 that the full truth came to light during a war tribunal held in Shanghai at which several Japanese officers were tried for war crimes. After the American pilots were arrested, they were imprisoned under very poor conditions. On August 28, 1942, three of them, Lieutenant Hallmark, Lieutenant Farrow and Corporal Spatz, were found guilty of war crimes without being told what the charges were. They were sentenced to death and executed on October 15 in the public cemetery in Shanghai. The remaining five were imprisoned under appalling conditions. Due to poor nutrition, the men soon suffered from dysentery and other diseases. In April 1943, the five prisoners were transferred to Nanking, where Lieutenant Meder died of malnutrition on December 1 of the same year. Afterwards, the remaining four Lieutenants, Nielsen, Hite and Barr and Corporal DeShazer, received better treatment, allowing them to survive the war. They were liberated by American troops on August 15, 1945.

The five-man crew of the B-25 Mitchell, interned in the Soviet Union, was transferred in 1943 to Ashgabat, 20 miles north of Iran in present-day Turkmenistan. Diplomatic efforts by the US government to free the five airmen had been unsuccessful for almost a year. However, Captain York and his crew were able to escape surprisingly easily from their new home in the south-west of the Soviet Union and were taken by smugglers to the British Consulate in Iran where they arrived on May 11, 1943. Documents released after the war showed that the NKVD, the predecessor of the KGB secret service, had staged the escape thereby maintaining the appearance of neutrality towards Japan.

The Doolittle Raiders had managed to complete a non-stop flight of over 2,250 miles (about 4,100 kilometers) with B-25 Mitchell bombers. This opened up many opportunities for the US Air Force to conduct further technical research into long-range bombers. These would come in the form of the Boeing B-29 aircraft nicknamed Superfortress, the main successor to the B-27 Flying Fortresses. The B-29s, unlike Doolittle's 16 B-25 Mitchells, would inflict huge damage to Japanese cities. Furthermore, the Doolittle Raid was the first occasion on which the US Navy worked closely with the US Army. Important lessons were learned that would be put to advantage in future amphibious landings on Pacific islands.

Definitielijst

- neutrality

- Impartiality, absence of decided views, the state of not supporting or helping either side in a conflict.

- Raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- war crimes

- Crimes committed in wartime. Often concerning crimes committed by soldiers against civilians.

Information

- Article by:

- Peter Kimenai

- Translated by:

- Simon van der Meulen

- Published on:

- 16-03-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!