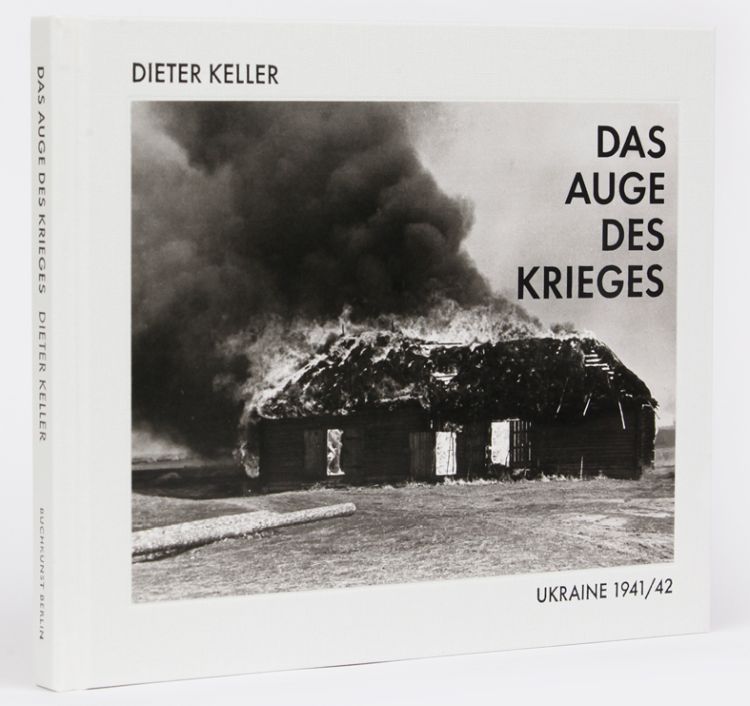

| Title: | Das Auge des Krieges - Ukraine 1941/42 |

| Writer: | Keller, D. |

| Published: | Buchkunst Berlin |

| Published in: | 2020 |

| Language: | German |

| ISBN: | 9783981980523 |

| Order: | www.buchkunst-berlin.de |

| Description: |

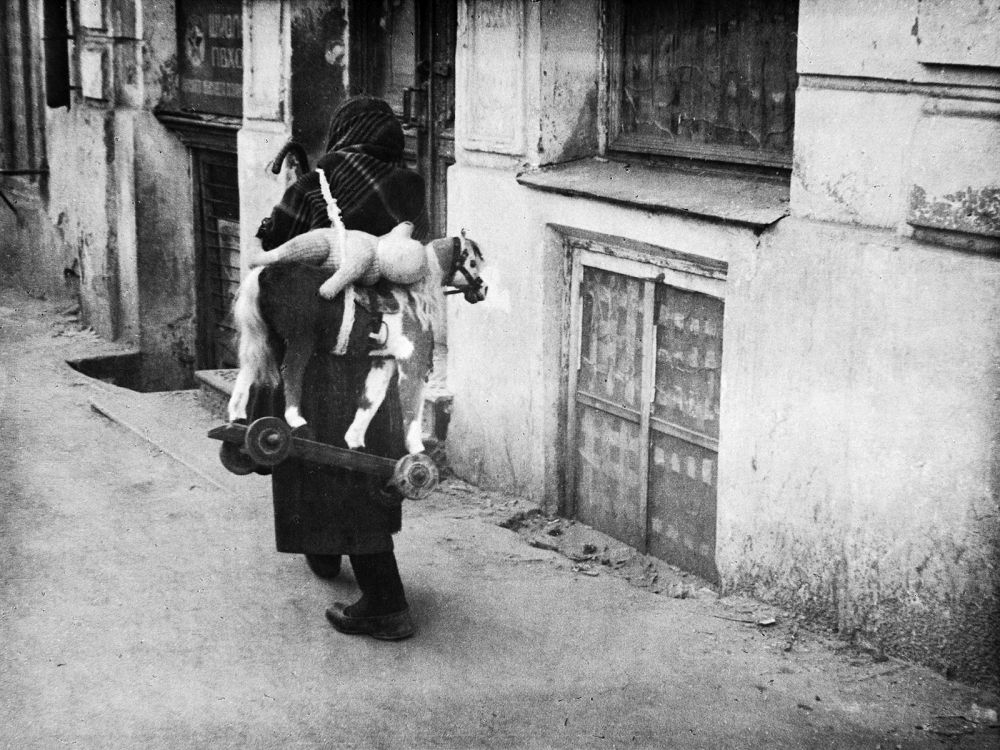

Dieter Keller (Stuttgart, 1909-1985) was the son of Walther Keller, who together with Euchar Nehmann took on the already successful publishing house Frankh-Kosmos. The publisher, which is still in existence, was at the time strongly focused on the production of board games, of which 'The Settlers of Catan' is the most famous. In the 1920s and 30s, Frankh-Kosmos was mostly known for its popular science publications. On the eve of the First World War, their magazine ‘Kosmos’ had a circulation of 100,000. Just before and during the first years of the Second World War, the youthful Keller was friends with many different artists from the Bauhaus and Neue Sachlichkeit (the New Objectivity) movements. A core principle of the Bauhaus movement was that there is no distinction between artists and artisans: the profession of 'artist' did not exist. The artist is, if you like, a craftsman who had transcended himself, and craftwork is the basis of all art. The ideas emanating from the Bauhaus movement would go on to have an important influence on architecture, the plastic arts and industrial production. Under the influence of the Dutch art movement De Stijl, Bauhaus gradually changed from an expressionist to a modernist movement. The Neue Sachlichkeit movement had appeared at the end of the First World War as a reaction to expressionism, but when the Nazis came to power in 1933 it was labelled Entartete Kunst (degenerate art) and immediately prohibited. Emotionless reproductions of everyday scenes and a preference for simplicity typified this style. Neue Sachlichkeit manifested itself in the film industry as well as in photography, architecture and painting. Keller's photographic work was strongly influenced by the two cross-pollinating art movements. Keller was a friend of the painter, sculptor and actor Oskar Schlemmer in particular (Stuttgart 1888 - Baden-Baden 1943), and correspondence between the two men, which exists of ninety letters, has been preserved. During much of 1941 and 1942, the then 32-year-old Keller was a soldier on active duty in the border region between Ukraine and Belarus. The German army had attacked the Soviet Union on June 22 1941 in Operation Barbarossa. By August 7 1941, Kiev had been captured and by September 1 1941 the entire region had been conquered. In anticipation of the attack, Erich Koch was appointed Reichskommissar for the planned Reichskommissariat Ukraine on July 16 1941, which was formally established on September 1. The region, which was governed as a colony, encompassed the whole of Ukraine, parts of the current Belarus, and parts of pre-war Poland. The German occupiers immediately began to carry out massacres and large-scale persecution of Jews took place. Einsatzgruppen were deployed directly behind the Wehrmacht's frontlines to carry out their gruesome work. Finding accomplices amongst the local population was not a problem, as following the Holodomor famine of 1932-33 (a forced collectivisation of agricultural businesses during which a fifth of the farming population - five to ten million people - lost their lives), the Germans were at first welcomed as liberators. At the time of Keller's presence, an enormous wave of violence swept the region, which could not have passed unnoticed by anyone. How, then, can Keller's presence in the region be explained? In the brief biography of the photographer it merely states: 'Details of Dieter Keller's deployment in the German Wehrmacht are unavailable. Previous research indicates that he was assigned to administrative duties.’ We have to take this at face value, and given Keller's involvement with the Bauhaus and New Objectivity art movements, which were banned and persecuted by the Nazis, we can surmise that a potential opponent of the regime may well have been 'tucked away' in a harmless administrative position. In the 1930s, amateur photography was much encouraged by Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels. The Nazis wanted to profit from the newly widespread availability and popularity of cheap cameras. Many photos were also taken by Wehrmacht soldiers during the war, mostly at the Eastern front. However, not everything was allowed to be photographed. From 1941 onwards, when things turned ugly on the Eastern front, it was strictly forbidden to photograph deceased German soldiers and the German authorities realised that it wasn't a good idea to let executions be photographed either. However, not everyone complied with the restrictions. A multitude of photos were made of executions of Jews, partisans hanging from the gallows and indiscriminate atrocities. Millions of photos, often of debatable quality, were left gathering dust for years in German cellars and, despite ever increasing amounts of work being made public, it is likely that there are millions more photos that remain hidden away. The photos that came to light soon after the war gave the impression that the whole war was seen by the Wehrmacht not as a matter of death and destruction, but as a kind of school outing. Soldiers often photographed themselves and their fellow soldiers, the cities that they visited and their exuberant parties 'mit Wein und Gesang'. This helped to propagate the myth that the Wehrmacht was not guilty of war crimes; that was the scandalous work of the SS. This illusion persisted for many years before finally being shattered. Dieter Keller was undoubtedly well aware that he had to be careful when taking photos, because these images are far removed from the above-mentioned 'tourist pics'. Despite the surveillance and censorship, he was able to take a number of film rolls with his Fedka (a Russian replica of a Leica) and smuggle them to Stuttgart. After the war he developed them at home and printed 201 unique large-format photos. In 1958 all the negatives were lost to fire, the earlier prints were saved. No other work by Keller from before, during or after the war is known. It is likely he was too occupied by his daily affairs: after the war he became the owner of the biggest offset printers in southern Germany. That is unfortunate, because he was a very able photographer. The photos in the German-language photobook ‘Das Auge des Krieges’ show a diversity of subjects. There are jolly portraits of Ukrainian and Jewish children, but also shocking photographs of dead soldiers, shot-off limbs, and horses that were violently killed or that did not survive the harsh winter conditions. Numerous burning houses bear witness to the violent character of the German advance. There are mysterious photos of remnants of buildings in the snow, that at first sight look like the ancient remains of a Middle-Eastern desert. Then innocent landscapes with a threatening air that forebodes something sinister. Four hacked-off swan heads, displayed in a cloverleaf formation. Dilapidated buildings which, after bearing witness to burning houses earlier in the book, immediately makes you think that the same fate will not be long in arriving. Stylistically, all the work is of exceptionally high quality, and the publisher rightly remarks that some photos recall the atmosphere of works of Hieronymus Bosch and Francisco de Goya. It is impressive that someone in the middle of the violence of war can preserve the necessary calm to take these beautifully detached photos. But what is Keller's goal here? The photos have absolutely no indication of place or time, let alone a description of any kind. There is a complete lack of historical context. It is simply a collection of images of which the underlying connections are not immediately clear. We know that the Nazis often forced people into buildings before setting them alight, leaving the victims behind like burning torches. Are these photos, then, proof of possible war crimes? Or are they in fact war trophies? Are the images still relevant, or just the sinister work of an artistic voyeur? And is it actually important to know what the intentions of the photographer were? At some point, photos surely take on a life of their own that is completely separate from the timebound intentions of the creator and the manner in which they were judged in their time. These images illuminate features that are present in every war, and we cannot exclude that this is precisely Keller's intent. Given the title, it seems that the publisher is also of this opinion. It is in any case impressive craftmanship, as befits a true Bauhaus disciple. |

| Rating: |     Very good Very good |

Information

- Translated by:

- Tomas Brogan

- Article by:

- Frans van den Muijsenberg

- Published on:

- 18-04-2021

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Images

Bron: Dieter Keller / © Dr. Norbert Moos.

Bron: Dieter Keller / © Dr. Norbert Moos.

Bron: Dieter Keller / © Dr. Norbert Moos.

Bron: Dieter Keller / © Dr. Norbert Moos.