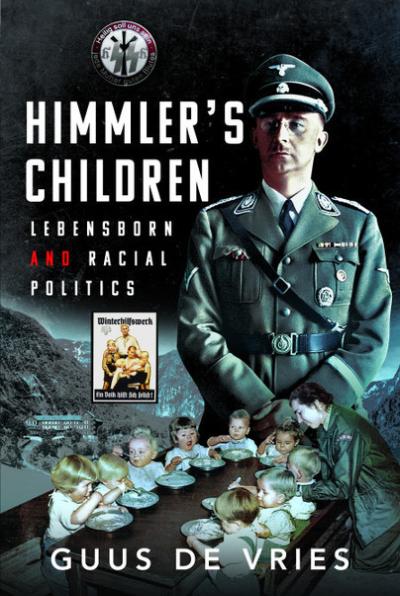

| Title: | Himmler's Children - Lebensborn and Racial Politics |

| Writer: | Vries, Guus de |

| Published: | Pen & Sword |

| Published in: | 2024 |

| Pages: | 292 |

| Language: | English |

| ISBN: | 9781399080552 |

| Review: | The August 13, 1945, issue of the American magazine Life featured a photo special by the famous photographer Robert Capa. And this time, there were no sensational action photos, as Capa took of the Allied landing in Normandy, for example, but portraits of babies and toddlers. There was nothing special about the images themselves, quite unlike the corresponding text, which was riddled with hate. "Super babies," was how the headline referred to the little ones. One caption read, "Stuffed and fattened in the care of Nazi nurses, they are a problem for the Allies that has yet to be solved." The site where the photos were taken was Hohehorst Castle near Bremen, where British troops had arrived on May 5. Besides children, they found mothers and nursing staff. All of them were staying here because the castle, under the name Heim Friesland, served as a children's home of the SS organization Lebensborn. In his book Himmler's Children, Guus de Vries describes the history of Lebensborn. This foundation, created in 1935 by SS leader Heinrich Himmler, oversaw maternity clinics and children's homes for 'racially pure' children and their mothers both in Germany and abroad. Many of these were illegitimate children of German soldiers or SS officers. Both the little ones and their mothers were pampered, since for Himmler it was a matter of great urgency to boost the birth rate, as long as the "Aryan" lineage of the boys and girls was guaranteed. According to De Vries, they were to become "the new nobility" of the Third Reich. Reports such as those in Life added to the fact that the victors viewed the Lebensborn homes as glorified brothels or breeding facilities for Nazi babies. Popular media, such as the 1961 movie "Ordered to Love," bolstered these myths.In his book, De Vries separates fact from fiction and places Lebensborn in a broader perspective. Since the organisation and its goals cannot be viewed in isolation from Nazi racial politics, he starts his book with three chapters explaining how the Nazis got their racist and eugenic ideas and how they put them into practice. The author argues compellingly that Lebensborn was part of nefarious politics that sought "racial purity". This politics included the genocide of Jews, the disabled and "inferior" Slavic peoples. Himmler was Hitler's main enforcer of this racial politics and, according to De Vries, considered Lebensborn his dearest project. "He himself became president of the association," the author sums up, "put the management of the organisation in the hands of people he knew personally and frequently visited establishments. He intervened in the smallest details in the clinics, drew up regulations and made recommendations, became godfather to children born on his birthday and sent them gifts." Between 1936 and 1944, about 30 clinics, homes and boarding houses were opened by Lebensborn. Thirteen of these were located in Germany and annexed Austria, 11 in Norway and the rest in Belgium, Luxembourg, Denmark, France and Poland. Gradually the racial requirements were somewhat lowered so that French mothers, for example, were also allowed in, despite not belonging to the "Nordic race" according to National Socialist racial standards. In The Netherlands, a seized and then renovated building in Nijmegen in 1943 was made available to function as a maternity clinic and children's home, but it never became operational. De Vries describes all the establishments, which were often located in former hotels, sanatoria or country houses in rural surroundings. Women and children could regain their strength, at a safe distance from wartime German cities ravaged by Allied bombing. Some 8,000 births were registered in the German facilities alone. Not all children in Lebensborn's homes were actually born there. The SS abducted racially suitable children from occupied Poland, among other places, to be adopted by "Aryan" families through Lebensborn. Disabled children born under Lebensborn became victims of the Nazi euthanasia programme. One such example that the author recalls is a little boy named Jürgen Weise who was born on 5 June 1941 in Heim Pommern in Bad Polzin (today Połczyn-Zdrój in Poland). Once it was noted that the child was mentally underdeveloped, it was decided that it should be taken to a psychiatric institution. The leader of the maternity clinic later reported to Gregor Ebner, the medical director of Lebensborn, that the child had died in Landesheilanstalt Görden on February 23, 1942. In most cases, the cruel deaths of Jürgen Weise and other mentally or physically challenged children were the result of withholding fluids and food combined with administration of an anaesthetic. In his book, De Vries also describes the individuals who were responsible for running Lebensborn's organisation and homes. One remarkable person is Inge Viermetz, whose career within the foundation began at Lebensborn's Munich office where she worked as a shorthand typist. She quickly worked her way up to deputy leader of Lebensborn's main department, over which she was, in practice, in daily charge. This went against Nazi ideology: women were mainly meant to raise children and were not supposed to occupy high positions. As the author puts it, Viermetz "must have had an especially strong character in the male-dominated Third Reich". He concludes: "Viermetz was one of the few rare exceptions who managed to obtain - and maintain - a position in which she interacted as an equal with members of the SS, party and government officials." In the final chapter, De Vries describes the fate of perpetrators and victims after the war, noting that Lebensborn's leaders received lenient sentences. In Nuremberg, Ebner defended himself during a trial brought by the Americans, arguing that the concept of "race" had played no role with Lebensborn. He was only convicted of membership of the SS and released because his remand had lasted long enough. In late 1949, a Munich court did impose a hefty fine on him plus community service and a five-year professional ban. After he requested clemency, he was still allowed to continue his work as a general practitioner. Viermetz was also released and subsequently acquitted in Munich. Both US and West German jurisprudence did not recognise what De Vries does acknowledge, namely that Lebensborn's enforcers were indeed (partly) guilty of Nazi crimes, such as child abduction and murder disguised as euthanasia. His well-researched and abundantly illustrated book, which includes endnotes and a source list, puts Lebensborn in its proper place in the history of the Third Reich. |

| Rating: |     Very good Very good |

Information

- Translated by:

- Sophie Louwers

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Published on:

- 19-08-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!