Oswald Kaduk, ‘Papa Kaduk’ or a monster?

When Oswald Kaduk was called a swine on April 6, 1964, the news spread like wildfire all over the world. The insult was made in Frankfurt am Main, in a hall converted into a courtroom. Here, 22 men stood trial for crimes they had committed in the concentration and extermination camp Auschwitz during the war. The man who was insulted was one of them. Between 1942 and 1945 he had grown into one of the most feared and brutal guards in the Nazi camp in Poland. ‘Outburst stirs Auschwitz Trial,’ the New York Times reported the next day. According to a reporter, someone in the audience had disturbed the trial by yelling loudly ‘beat that swine to death,’ referring to Kaduk.

This was shouted out after a witness had testified that the SS guard had herded a group of 12 Jewish children between four and 11 years old to the gas chambers at gun point where they all would have been gassed. The defendant immediately denied the accusation. ‘Liar, liar,’ he yelled at the witness. The latter didn’t hold back and retorted, ‘Now you don't have a gun and at long last we can speak to one another!’[1] This triggered the insult from the audience mentioned before. After a failed attempt by Kaduk’s lawyer to determine who had yelled, the trial was resumed.

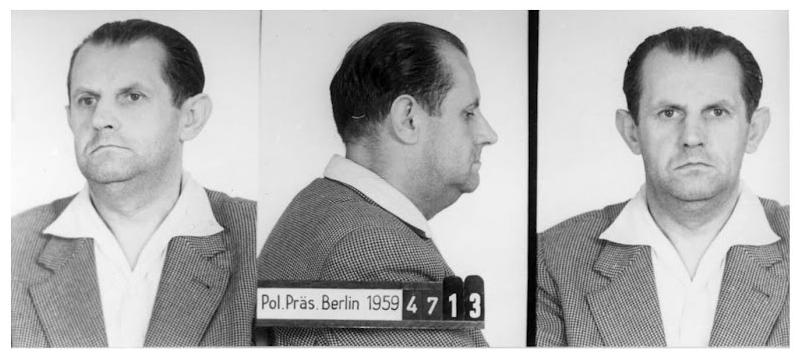

Police photos of former guard Oswald Kaduk prior to the Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt-am-Main. Source: Berlin Police, via Google Arts & Culture

Police photos of former guard Oswald Kaduk prior to the Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt-am-Main. Source: Berlin Police, via Google Arts & CultureA swine

A journalist of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, however, would write in his article about the trial that it hadn’t been someone from the audience, but the witness who had called the defendant a swine. The witness did this after having testified how ‘a dozen little Jewish girls, ages 3 to 11’ had begged him to save them from the gas chamber. ‘They said they were strong and could work and didn’t want to die,’ the man continued his testimony. ‘There was Oswald Kaduk, with gun in hand. That murderer Kaduk drove them away to the gas chamber.’ Thereupon he pointed to Kaduk in the dock who then called him a liar. After that, the witness is said to have called him a swine. The article continued with: ‘Spectators yelled, “Beat him to death!” It took presiding Justice Hans Hofmeyer several minutes to bring order back to the court room.’[2]

The reports about the event differed in detail, but we can be certain about the identity of the witness, as well as about the brutality of the defendant. The witness was Ludwig Wörl. If he were the one to call Kaduk a swine, he had all sorts of reasons to do so. The Munich resident himself had been imprisoned for 11 years in the camps of Nazi Germany, almost as long as the Third Reich had existed. During that period, he had to endure the denigration, the cruelty and the dismal conditions for which men like Kaduk had been responsible. To Wörl, Kaduk and his codefendants were the personification of the injustice imposed on him. During the so-called Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt it was his mission to contribute to ensure that justice would be done and the defendants put behind bars.

The reconstructed execution wall between Blocks 10 and 11 in the Stammlager (main camp) Auschwitz. This is where prisoners were executed by Oswald Kaduk and his colleagues. Source: Richard Broekhuijzen / Wikimedia Commons

The reconstructed execution wall between Blocks 10 and 11 in the Stammlager (main camp) Auschwitz. This is where prisoners were executed by Oswald Kaduk and his colleagues. Source: Richard Broekhuijzen / Wikimedia CommonsSadistic executioner

During the trial, Kaduk’s cruelty became crystal clear. ‘No defendant appeared more unsophisticated and brutish than Oswald Kaduk,’[3] historian Rebecca Wittmann wrote in Beyond Justice, her study about the West-German Auschwitz trial. Based on testimonies of former prisoners, including Ludwig Wörl, an image emerged of a sadistic executioner with many deaths on his conscience. Wörl testified how he had seen the SS man frequently participating in executions on Tuesdays near the so-called black wall between Block 10, where medical experiments on inmates were conducted, and Block 11, the camp prison. In his words, 26,000 inmates from Block 11, where he had been imprisoned himself for a few months, had been executed. ‘I can state with certainty that Kaduk has taken part in it,’ he said during an interrogation. ‘He has also fired at prisoners without killing them right away.’[4]

In addition to shooting and gassing, Kaduk killed his victims by drowning, strangulation and hanging. When he appeared, frequently drunk with his whip in hand, inmates knew they had to get away. If he was in a bad mood, he would randomly select one or more prisoners to let loose his cruelty. Particularly notorious was his preference to kill prisoners with a walking stick which he, with his victims lying on the ground, laid across their necks and stood on until they suffocated. The description of these and other atrocities by the camp guard filled no fewer than 15 pages in the indictment against him.

Normal life

Kaduk was one of the many Nazi war criminals who had lived a perfectly normal life before and after his career as camp guard. He was born on August 26, as one of seven children of a blacksmith in Königshütte in the coal region of Upper-Silesia. Today, the largest part of the area is Polish territory, and Kaduk’s place of birth can be found on the map as Chorzów. Some 25 miles from the former German village is the location where the Auschwitz concentration camp would be opened in 1940. Before Kaduk entered service as camp guard, he completed the Volksschule (elementary school) and worked as a butcher’s apprentice. In 1924 he passed his butcher’s exam. After employment in a local slaughterhouse, he subsequently worked as a professional local firefighter and in a chemical factory.

At the end of 1939, Kaduk enrolled in the Allgemeine-SS and then took basic training in the Waffen-SS in the 15. Totenkopfstandarte in Oranienburg. Fighting on the Eastern Front, he contracted malaria, causing him to stay in an army hospital for a long time. Subsequently he was declared unfit for duty at the front. At the end of 1942, he was transferred to Auschwitz which was described, he said, as a training camp for troops. According to him, he was told he would return to the front after a training of six months. In an interview with a German documentary filmmaker in 1978, Kaduk declared he had been shocked on entering the camp. He had felt particularly shocked by the large number of prisoners. Instead of receiving military training in Auschwitz, he was deployed as a camp guard.

Male nurse

After initially having served as a regular guard, Kaduk was promoted to Blockführer and subsequently to Rapportführer. In that last position he was responsible for the daily count of prisoners on the parade ground. The highest rank he reached was SS-Unterscharführer (junior squad leader). After the evacuation of Auschwitz in January 1945, he was deployed in Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria, where he and other guards fled before the camp was liberated on May 5 by units of the American Third Army of General Patton. After the German capitulation, the former camp guard managed to blend unnoticed into German society for over a year. He had a job in a sugar factory in Löbau in the German federal state of Saxony in the Russian zone of occupation until December 1946, when he was recognized by a former Auschwitz inmate and arrested by a patrol of Russian soldiers.

On August 27, 1947 a Soviet court sentenced him to 25 years’ forced labor, but he was granted amnesty in 1956. On April 26 that year, he was allowed to leave the Bautzen correctional institution as a free man. He left the GDR and went to work as a male nurse in West-Berlin. While the former camp executioner made himself highly appreciated by his patients as a nurse, the public prosecutor in Hessen, Fritz Bauer, and the president of the International Auschwitz Committee, Hermann Langbein, managed to persuade the court in Frankfurt am Main to make preparations for the case against former staff members of Auschwitz.

Auschwitz trial

Before the Auschwitz trial was launched in 1963, Oswald Kaduk had been taken into preliminary custody in July 1959. His former sentence by a Soviet court was irrelevant as the Federal Republic didn’t recognize Soviet verdicts. In December 1963, the trial started against him, 20 other members of the SS, and a Kapo (an inmate supervising other inmates). The former Rapportführer was indicted, among other things, for having made selections for gassing and for beating and strangling prisoners leading to death. He denied all charges and considered himself a victim because, as he said, during his imprisonment in Bautzen he had seen 25 comrades die. The demise of prisoners in Auschwitz was, in his opinion, comparable to the demise of civilians during Allied bombings. That he had shot prisoners himself was a lie, he claimed; he had used his gun only twice and then just to fire warning shots.

All of Kaduk’s denials were refuted by the numerous testimonies of former inmates. The camp executioner had committed all his crimes in public after all. An example discussed in Frankfurt was the game of ‘cap throwing’ for which Kaduk usually selected new prisoners. He made his victims throw their caps into the forbidden zone along the fence and ordered them to retrieve them, knowing they would be shot by the guards in the watchtowers. Recently arrived inmates did not know they were in danger while retrieving their caps, and so they walked into the trap set by Kaduk. Although he hadn’t fired the lethal shots himself, he would be sentenced for these provoked murders nonetheless.

Ludwig Wörl

Ludwig Wörl’s testimony, targeted at other defendants in addition to Kaduk, was considered not entirely trustworthy by the court. During an interrogation by the prosecutor, the former prisoner had claimed that defendant Emil Hantl had administered a lethal injection to various prisoners, but later before the investigative judge Wörl stated that he had only seen Hantl in the room, not knowing whether he had personally administered injections. The assumption emerged that Wörl had been making up or exaggerating stories to get the defendants behind bars. On sentencing Kaduk, doubts about Wörl’s credibility played no role. Based on all evidence presented, on August 19, 1965, the former guard was pronounced guilty of 10 murders and complicity in at least 1000 murders. He was sentenced to life imprisonment.

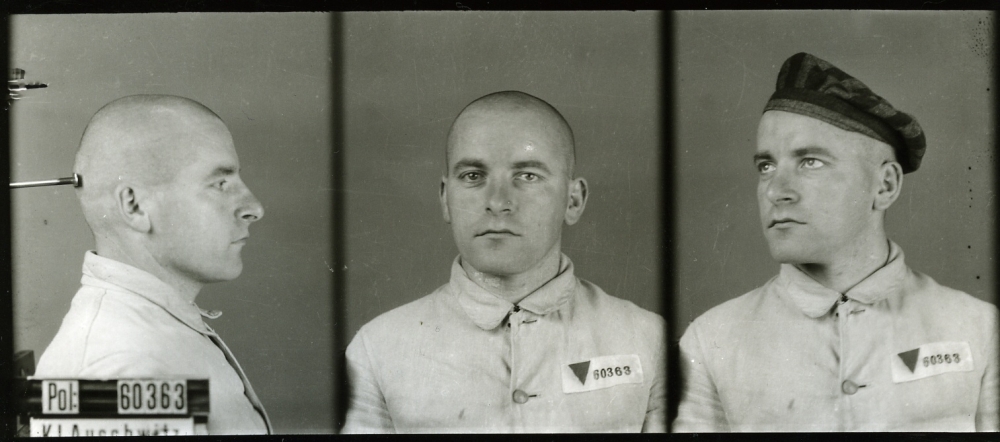

Photographs taken of Ludwig Wörl during his captivity in Auschwitz. Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau in Oswiecim

Photographs taken of Ludwig Wörl during his captivity in Auschwitz. Source: State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau in OswiecimApart from the disruption of order during Wörl’s testimony, the press paid much attention to all excesses that were discussed during the trial. The atrocities committed by someone like Kaduk on his own initiative and apparently with great pleasure, were easier to condemn than the collective participation of guards in mass murder ordered by the government. As for Kaduk, journalists showed great surprise about a letter sent to the court in defense of the ‘monster’ named Kaduk. In their letter, patients of the hospital in West Berlin where he worked, voiced their sympathy for the caring and friendly nurse, as they had gotten to know the former camp guard. In the hospital, he was even called ‘Papa Kaduk’. How could it be that a cruel camp guard turned into a model citizen after the war, journalists wondered.

For witness Wörl, it must have been all but impossible to envisage the SS man as an appreciated nurse. In Auschwitz, he had come to know Kaduk as a merciless sadist. During a large part of the years Wörl had spent in concentration camps, he had devoted himself to the care of fellow prisoners. Without medical education, he was put to work as a nurse in concentration camp Dachau. In Auschwitz he was even put in charge of the entire camp hospital. It was in this role that he managed to save many lives, including those of Jewish fellow prisoners. Recognition of his heroic actions in his own country would follow only after the end of the Auschwitz trial. However, before then, in 1963, he was the first German who was named Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem in Israel.

Righteous behind Barbed Wire

In his book Righteous behind Barbed Wire Dutch writer Kevin Prenger tells the story of Auschwitz survivor Ludwig Wörl and that of human rights activist Armin T. Wegner. Both of these non-Jewish Germans stood up for their Jewish compatriots, actions for which they were honored after the war as Righteous among the Nations by the Israeli Holocaust Memorial Center, Yad Vashem. In addition to caring about the fate of Jews in Germany, Wegner and Wörl had another thing in common: they were themselves victims of persecution by the Nazis and were political prisoners in Hitler’s concentration camps. How did they get there, and what did they do to defend their fellow Jews from Nazi hatred?

- Righteous Behind Barbed Wire

- Armin Wegner & Ludwig Wörl

- ISBN: 9798336367638

- More information about this book

Notes

- ‘Outburst Stirs Auschwitz Trial’, The New York Times, April 7, 1964.

- ‘Auschwitz Trial Hears of SS Man Who Sent 12 Little Jewish Girls to Death’, April 7, 1964, Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

- Wittmann, Rebecca, Beyond Justice, p. 140.

- HHStAW, 461, 37638/73, Mulka, Robert u.a. (1. Auschwitz-Prozess): Hauptakten Band 72, p. 11377.

Used source(s)

- Source: Kevin Prenger

- Published on: 27-01-2025 20:33:12

Related persons

Background stories

Latest news

- 16-02: Armin T. Wegner and his letter to Hitler

- 14-02: The hugely popular ‘Standing with Giants’ installation returns to the British Normandy Memorial

- 27-01: Russia focuses on Soviet victims of WW2 as officials not invited to Auschwitz ceremony

- 12-'24: Christmas and New Year message from our volunteers

- 11-'24: New book: Righteous Behind Barbed Wire

- 11-'24: Postal artifacts provide a vibrant testament to the experiences of the Dutch people during WWII

- 10-'24: DigitalBattlefieldTours unlocks military tactics to a wide audience

- 10-'24: Lily Ebert, Holocaust Survivor, Author and TikTok Star, Dies at 100

- 10-'24: Commemoration 7th Battalion the Hampshire regiment

- 10-'24: Discover the story of the V-weapons