Armin T. Wegner and his letter to Hitler

On April 1, 1933, the mood in many shopping streets in Germany was grim. Sturdy men in brown shirts with a black swastika on a red and white band on their upper arm were standing in front of large warehouses as well as tiny shops. These places had not been selected at random by members of Hitler’s Sturmabteilung or SA. Stars of David in white paint on shop windows and the text on the Nazi protest signs made it clear. ‘Germans, take care! Do not buy from Jews!’ was the slogan of the day.

Brown shirts in Berlin during the anti-Jewish boycott of April 1, 1933. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-14468 / Georg Pahl / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Brown shirts in Berlin during the anti-Jewish boycott of April 1, 1933. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-14468 / Georg Pahl / CC-BY-SA 3.0It required courage to ignore the malicious SA stormtroopers and enter Jewish shops. You could expect to be called a Jew friend at the very least. Yet, this boycott of Jews, orchestrated by the Nazis, was ignored by a large segment of the shoppers. Hitler had been Reichskanzler for only two months, and his regime did not yet strike fear in the average German as it would later on. Whoever bought a small bottle of perfume in the Wertheim warehouse on Leipziger Platz in Berlin, owned by the Jewish family of that name, or meat from the local Jewish butcher, could do so without being arrested. The Jews were the ones who got the short end of the stick, with their shop windows smashed, a warning of what was in store for them in future years.

The brown beast

The anti-Jewish boycott of April 1, 1933, was the reaction of the German government to a boycott of German goods, set up by Jewish organizations in the USA and Europe. ‘Judea Declares War on Germany’ was the headline of the London tabloid The Daily Express on March 24, only fueling the fire. Instead of a declaration of war, the call by the international Jewish community was an act of protest against the bullying and violence the Jews in Germany had to endure after the Nazis had seized power on January 30. During the first weeks of Hitler’s reign and partly as revenge for the critical attitude of foreign Jews, members of the SA arrested prominent Jews in various cities in Germany and locked them up in improvised concentration camps where they were treated brutally.

In various cities, Jewish judges and lawyers were denied entrance to the courts. The anti-Semitic violence reached a temporary low point on April 1 when the boycott resulted in the destruction and looting of shops and the beating of Jewish shop owners. Officially, the boycott lasted only one day, but SA members would continue making life difficult for German Jews. Their power decreased, however, when on June 30, 1934 during the ‘Night of the Long Knives’ the top of the SA was either executed or locked up. The ‘brown beast’ was tamed in this way. A new, even larger eruption of violence was awaiting the Jews though. This would take place in November 1938 and would become known as the Kristallnacht or the Night of the Broken Glass.

Anti-Jewish legislation

Hitler was not bothered by his followers’ harrassment or mistreatment of Jewish citizens. He was bothered by the SA’s increasingly seeking its own way and by the difficulty of keeping its members in check. Uncontrolled public violence would turn Nazi Germany into a pariah within the international community, and Hitler wanted to prevent that as long as he didn’t have an unassailable position of power and a mighty army at hand. Anti-Semitism was to be implemented in a ‘civil’ way by laws and decrees. The first important law was issued as early as April 7, 1933, and entailed the exclusion of Jews from governmental functions, resulting in the discharge of Jewish administrators, judges, teachers and other functionaries paid by the government. Similar legislation followed the next month for Jewish physicians and lawyers. Another decree stipulated that the number of Jewish students in educational institutions was limited to 1.5% of the total. The equal rights which the Jews had gained in Germany in the nineteenth century after years of discrimination were a thing of the past.

As a result of this anti-Semitism, many prominent Jews and other opponents of the Nazis left the country in the first years of Hitler’s reign, sometimes out of protest but mainly out of the wish for survival. On March 28, 1933, a man with untidy white hair and a brushy mustache entered the German consulate in Antwerp to hand in his passport. Albert Einstein was his name, as the official of the consulate read in that document. The winner of the Nobel prize in physics of 1921, whose pioneering formula E=mc2 had opened up a new chapter in natural science, had just returned to Europe after a visit to America. He decided not to return to Germany where he, a well-known Jewish scientist with pacifist ideas, no longer saw a future for himself. After he gave up his German nationality, he was stateless for many years until he was granted the American citizenship in 1940. His departure from Germany was a giant brain drain for German science, but the Nazis did not care. A genius mind was only acceptable as long as the owner was of Aryan descent.

Only a few Germans seemed to care about Einstein’s departure and that of the 37,000-38,000 Jews who made up the first wave of emigrants from Germany in 1933. No one took to the streets to protest, and Hitler was given a free hand to implement his anti-Semitic policy. Germans were unconcerned about those who committed suicide for fear of what would happen to them.

Letter to Hitler

Among the mass of the followers and the indifferent, there was one exception though. On Easter Monday, April 11, 1933 a Berliner took his pen in hand in order to voice his concern and displeasure about what was being done to his Jewish fellow citizens. ‘Herr Reichskanzler,’ he started his letter to Hitler which he addressed to the Braune Haus in Munich, the headquarters of the Nazi party. In plain language he criticized the boycott of April 1 and the subsequent anti-Semitic legislation. In his plea to revoke the anti-Jewish laws, he praised the role Jews had played for ages in the development and growth of Germany. As examples, he mentioned Einstein and Frits Haber. The latter discovered how to convert nitrogen from the air into ammonia, a basic ingredient of modern artificial fertilizer.

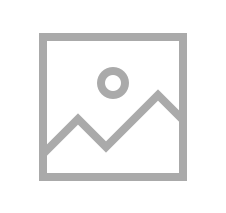

Armin T. Wegner in his elder years, photographed by Armenian photographer Tzolag Hovsepian. Source: Familiar Faces, Los Angeles, 2013 / Wikimedia Com-mons.

Armin T. Wegner in his elder years, photographed by Armenian photographer Tzolag Hovsepian. Source: Familiar Faces, Los Angeles, 2013 / Wikimedia Com-mons.According to the writer, the fate of the Jews was connected to the fate of Germany. Germany needed the Jews, just as the Jews needed Germany when they were chased away from other parts of Europe and found shelter in Germany. The Germans themselves, were they not a mixture of numerous peoples like the Franks, Frisians and Western Slavs? ‘Didn’t you yourself come to us from a neighboring country?’ he even dared to confront the chancellor, born and bred in Austria. ‘Lead the outcasts back to their jobs,’ he urged him, ‘the physicians to their hospitals, the judges to their courts, do not banish children from schools any longer, heal the worried hearts of the mothers and the entire population will be grateful to you.’[1]

Voice in the wilderness

Armin T. Wegner: with his own name the courageous German signed his letter. Martin Bormann, from July 1, 1933 chief of the staff of Deputy Führer Rudolph Hess, sent an acknowledgement of receipt. It is unlikely Hitler ever read the letter. There is also the question whether the author actually had the illusion his letter would make a change in the lives of his Jewish fellow men. With today’s knowledge, it can be seen as a naive, hopeless attempt, devoid of political reality. Nonetheless, it was an act which, according to the Israeli Yad Vashem Holocaust Remembrance Center, was reason enough to name Wegner in 1967 Righteous among the Nations. Still in the garden of the museum is the tree he planted himself when he was honored for the humane plea he addressed to Hitler in 1933.

In the Germany of that time, Wegner with his great sense of justice was a voice in the wilderness, an experience not unknown to him. Some fifteen years before, another minority group was cornered for which he became an advocate, namely the Armenian people persecuted by the Turkish state. During the First World War, as a German soldier he witnessed the effects of the Armenian genocide. He tried in vain to mobilize German politicians to act against this crime committed by an ally. After the war, it was the American president Woodrow Wilson to whom he addressed a letter in 1919 to plead for restoration of justice for the Armenians. So for people who knew Wegner, sending a letter of protest to Hitler was no surprise. ‘My father was like that,’ his son Michael said; ‘he didn't mince words about what he said. He was despairing that history would repeat itself: that the Jews would suffer equally from what he had experienced with the Armenians.’[2] The fate of the European Jews, still on the distant horizon in 1933, would even exceed the genocide of the Armenians.

Righteous behind Barbed Wire

In his book Righteous behind Barbed Wire Dutch writer Kevin Prenger tells the story of Auschwitz survivor Ludwig Wörl and that of human rights activist Armin T. Wegner. Both of these non-Jewish Germans stood up for their Jewish compatriots, actions for which they were honored after the war as Righteous among the Nations by the Israeli Holocaust Memorial Center, Yad Vashem. In addition to caring about the fate of Jews in Germany, Wegner and Wörl had another thing in common: they were themselves victims of persecution by the Nazis and were political prisoners in Hitler’s concentration camps. How did they get there, and what did they do to defend their fellow Jews from Nazi hatred?

- Righteous Behind Barbed Wire

- Armin Wegner & Ludwig Wörl

- ISBN: 9798336367638

- More information about this book

Notes

- Letter of Armin T. Wegner to Reichskanzler Adolf Hitler, April 11, 1933, on: www.exil-archiv.de

- Wernicke-Rothmayer, J. (red.), Armin T. Wegner, p. 82.

Used source(s)

- Source: Kevin Prenger

- Published on: 16-02-2025 19:29:29

Related persons

Latest news

- 12-04: Understanding the German side of the fighting in Normandy

- 03-03: A WWII helmet returns home 80 years after having been lost at Remagen Bridge, Germany

- 14-02: The hugely popular ‘Standing with Giants’ installation returns to the British Normandy Memorial

- 27-01: Russia focuses on Soviet victims of WW2 as officials not invited to Auschwitz ceremony

- 27-01: Oswald Kaduk, ‘Papa Kaduk’ or a monster??

- 12-'24: Christmas and New Year message from our volunteers

- 11-'24: New book: Righteous Behind Barbed Wire

- 11-'24: Postal artifacts provide a vibrant testament to the experiences of the Dutch people during WWII

- 10-'24: DigitalBattlefieldTours unlocks military tactics to a wide audience

- 10-'24: Lily Ebert, Holocaust Survivor, Author and TikTok Star, Dies at 100