Christmas far from home, GI’s in Europa during the Holidays of 1944

In 1944, Christmas was celebrated for the sixth time since the Second World War had broken out on September 1, 1939. Men who often shared the same religious background fought each other to the death in sharp contrast with the old Christmas message of Peace on Earth. Christmas under Fire, 1944 tells about this last war time Christmas. Below an excerpt from this book. This part is about how American GI’s shared Christmas with the Europeans that were liberated by them and about the tragedy with the Léopoldville.

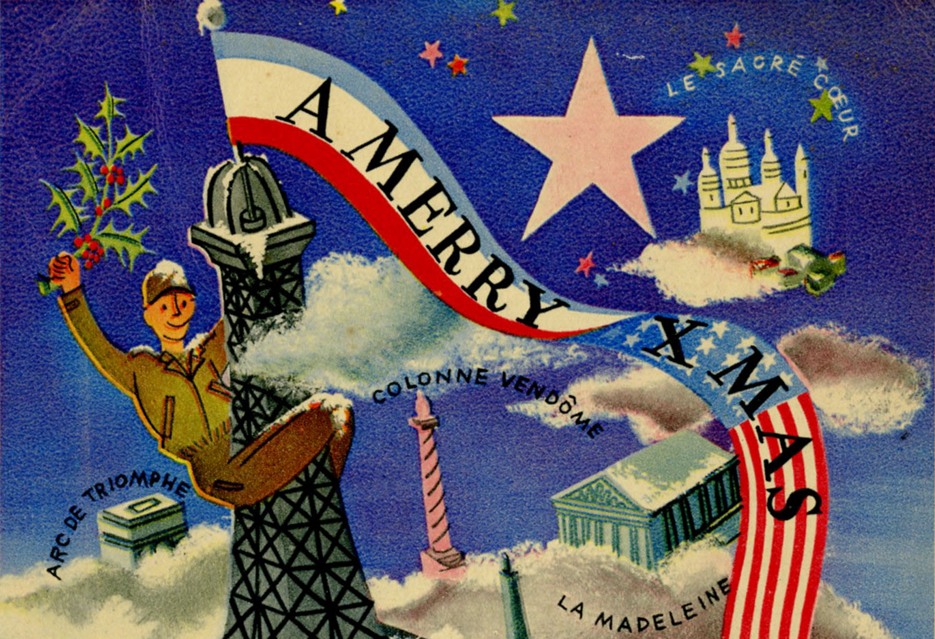

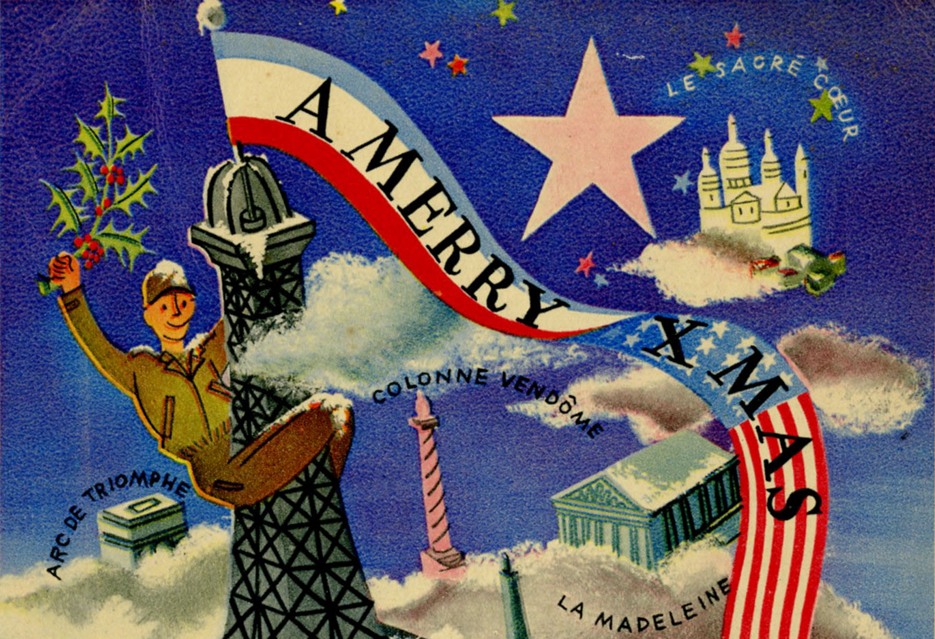

Part of a Christmas card GI's could send in 1944 to their friends and family overseas.

Part of a Christmas card GI's could send in 1944 to their friends and family overseas.

This Christmas, journalist Walter Cronkite was busier than during the previous two. Shortly after the start of the Ardennes offensive he was called to Paris to help out in the busy office of the United Press. Although he had been looking forward to a holiday celebration in the French capital, he had left for the front on Christmas Eve. Despite the cold, he was dressed in his normal clothing. Other items – long Johns, boots, gloves and a leather coat – he could not obtain before January 3rd, 1945. He worked for four days nonstop, but he judged he had little success as there were other journalists present who were better than himself. To his regret, it was only on December 27 that he managed to write a letter to his wife, telling her he had had an "awfully lonely Christmas – the worst ever, I think. I must admit that the surroundings weren't too unpleasant, but the fact that I was alone again without you made it almost unbearable." He spent Christmas Day in the city of Luxembourg which he described as "just as lovely as the post cards." At night he had a turkey dinner, along with Ernest Hemingway, Martha Gellhorn and other journalists. "We had some eggnog and everyone else, except old hard-working Cronkite, who had a fistful of mediocre stories to do, got pretty well pied. I had a few drinks and filed my last story about midnight after which I was so tired I just collapsed into bed."[1]

Tragedy with the Léopoldville

Walter Cronkite and his colleagues in Luxembourg had no idea that on Christmas Eve, a tragedy unfolded off the Normandy coast that would be kept under lock and key by the American army until 1959. The disaster took place in the English Channel where the Belgian troop transport vessel Léopoldville was on its way from Southampton in Great Britain to the European continent. The ship carried 2,223 American soldiers of the 66th Infantry Division who were to strengthen the forces in the Ardennes. The steamer, built in 1929, had been used for luxury cruises before the war, but nothing of that could be seen. Anything considered superfluous was removed in order to carry more passengers. Nevertheless, the vessel with 2,223 soldiers and a crew of 237 was overcrowded,[2] especially in the hold where soldiers made the journey, lying in hammocks and sitting at picnic tables in the passageways. "The stench aboard was really intense," passenger Vincent Codianni recalls. "Down below we were packed like sardines in a tin."[3] Far away from home on Christmas Eve, in heavy seas en route to a war zone, the spirit aboard was tense and depressed. If it wasn't fear or nostalgia the men felt, it was sea sickness. In these circumstances the trip was far from pleasant, but it would get much worse.

Somewhere near the Belgian vessel, the German U-486, commanded by Kapitän Gerhard Meyer, was lying in wait for prey. Aboard, the U-boat’s cook had made all preparations for Christmas. "He had baked a pie for everyone," according to a crew member. "The cream had been whipped. ... We had good food. We were ready for Christmas."[4] Suddenly all men were called to their battle stations. A convoy, including the Léopoldville, was spotted. Sinking an Allied ship justified postponing the Christmas celebration. Aboard the Belgian vessel, there was hardly any Christmas spirit. Despite the cold, some 20 soldiers had opted to leave the hold to sing Christmas carols in the fresh air on deck. To avoid being spotted by the enemy the vessel was darkened. The lights of Cherbourg, the ship's destination, were blinking in the distance, making the men feel at ease now that the journey would soon be over.[5] Suddenly, passengers and crew were shocked by a massive bang. In the hold, men were flung from their hammocks, and the crew called to them in Flemish to come up on deck.[6] Meanwhile, the U-boat that had fired the torpedo which struck the Léopoldville amidships descended to the seabed where she remained unseen and safe from depth charges.

As the freezing sea water rushed in below deck, everything that could go wrong did go wrong aboard the vessel. Panic broke out and the men had to struggle to get out of the ship's hold. Once on deck, they made the terrible discovery that the crew had already abandoned ship with all of the lifeboats, of which far too few had been aboard. Swimming vests were not available in sufficient numbers and safety instructions had not been given.[7] "I heard all kinds of yelling," Ed Phillips later declared about the situation on board. "I heard many boys calling for their mother. I did so too because the one person I really cared about was my mother."[8] Some men plunged into the freezing water while others jumped aboard the H.M.S. Brilliant, one of the escorts which had come alongside the Léopoldville. Hank Anderson, who had directed the singing of the Christmas carols on deck, watched some men stiffen at the prospect of having to jump. "These guys were paralyzed. They just would not jump. And they had seen some jump, and not made it. So it was quite a jump across. And I remember getting over there and sliding across what little deck there was, slammed into the bulwark that was there; staggered back up to the rail. And the sight that I had made it enabled them then to start jumping." He was safe but others misjudged their jump, landed between the vessels and were crushed.[9]

The Léopoldville sank around 20:45. Some 500 men had managed to board H.M.S. Brilliant safely while others still floated in the water. One of them was Ed Phillips who had to beat off several men to prevent him from going under. He was to be picked up by one of the vessels that had come to the rescue from Cherbourg, a mere 6.5 miles away.[10] Through miscommunication, the rescue operation had gotten under way far too late, resulting in numerous unnecessary victims.

Hank Anderson, who attributed his survival partly to the fact that he had left the hold to sing Christmas carols, told how he and the other survivors were taken care of in Cherbourg by black soldiers. "They surrounded us and sang Christmas carols. And I, I was so stunned."[11] A total of nearly 800 Americans would lose their lives either from drowning aboard the vessel, from hypothermia or from injuries sustained after they had jumped overboard. Captain Charles Limbor went down with his vessel too. A Belgian crew member and three Congolese also lost their lives.[12] This was not only a personal tragedy for passengers, crew and their next of kin but also a painful loss for the American war effort, yearning for reinforcements to be deployed in the Ardennes. Many of the rescued men were no longer fit for duty but had to recuperate in French hospitals from hypothermia or injuries.

A GI opens the Christmas package received from his wife. His buddies share the treat. European Theater, 1944. (Source: U.S. Army)Oranges

A GI opens the Christmas package received from his wife. His buddies share the treat. European Theater, 1944. (Source: U.S. Army)Oranges

Unaware of the sinking of the Léopoldville, American military personnel shared the festivities with civilians in various locations in Europe. In Savere in Alsace, liberated for the most part in November 1944 by American and French troops, Private First Class Peter Feyen played Santa Claus for 150 children, mostly orphans. Although he was in his usual battledress and he had a three-day stubble instead of a long white beard, the candy he distributed was no less tasty for the boys and girls who had not celebrated Christmas for four years. Men from his liaison unit with the air force had given the local youth their chocolate rations and candy from their Christmas parcels. In addition, they had brought toys from Paris and oranges from North Africa to hand out. "Some of the youngsters had never seen an orange before and weren't quite certain whether to eat the fruit or bounce it," reporter Seymour Korman wrote. The children experienced another first by watching a Mickey Mouse movie. The mayor of the village expressed his gratitude for what the Americans had done and added that the Germans had never made a gesture like that during the occupation.[13]

Oranges also played an important role in the recollections of Christmas 1944 of 1st Lieutenant Robert J. Fisher. Posted to the 544th Bomb Squadron, 384th Bomb Group, he was stationed at R.A.F. Grafton Underwood. He and his bombardier had been invited to Christmas dinner by an English family in their home in Northampton, 25 miles southeast of the base. As he did not want to come empty-handed, for a few days beforehand he and his mate each set aside the orange that came with their breakfast. Some of their friends donated their oranges too; so eventually they had collected some fifteen oranges as a hostess gift. When they handed the bag of oranges to their grateful hostess, she immediately put all but two or three of them into a beautiful bowl which she placed on the mantelpiece. She and her husband next peeled the oranges she had kept apart. "The lady then asked her husband to go get the neighborhood children and bring them over to the house," Fisher said years later. "When the children arrived, the wife and her husband gave each child a section or two to eat and let them smell and feel the peeling. We thought this a little strange and asked them why they did it that way. They explained that they just had to share with the neighborhood children because most of them had never even seen an orange before, let alone tasted one!" Fisher was happy his present had been received so well. He was pleased "to witness an outstanding example of the true Christmas spirit. I will never forget Christmas of 1944."[14]

First Christmas

In Paris, the Americans distributed champagne and cognac among the citizens. In their haste to leave town, the Germans had left thousands of cases of these beverages behind. For many of the youngest children in France this was the first time they celebrated Christmas after an occupation of four years. Over those years, their parents had had neither opportunity nor means to celebrate Christmas.[15]

Nicole, about eight years old, did not know what Christmas was all about either. She was the daughter of the resistance couple with whom 20-year-old soldier Vernon Alexander from Arkansas and his mate Paul had moved in. Alexander was a machine gunner in the 2nd Battalion, 411th Regiment. In the French village where his unit had been quartered he had selected the small family house as their shelter because it had a large bay window which offered a clear view of any Germans who might approach. Communication between the French and the Americans proceeded laboriously as they did not speak each other's language. The Frenchman, Nicolas, was recuperating from a groin injury he had sustained from an exploding grenade, and his wife Lucy was afraid of what might still be in store for her family. For yet another year, a somber Christmas awaited their little daughter, but the Americans refused to let that happen. "She needed an American Christmas," Vernon stated years later.

After Nicole had tasted chocolate for the first time thanks to the Americans, Vernon and Paul now went out of their way to let her celebrate a real Christmas. She had not experienced this before or she could not remember it. They left the safety of the village to cut down a tree which they decorated with garlands made with wrapping paper from parcels from the USA. In their camp they found two dolls which they wrapped up for the girl. For Nicole's father, who was risking his life sheltering Americans, they found a box of cigars and tobacco. While Paul distracted the mess sergeant, Vernon stole fried ham, flour, sugar and some fruit from the mess tent. They smuggled the food and the Christmas tree into the home of the French family.

The next morning, about a week before Christmas, when Nicole saw the tree with the presents under it, she shrieked with joy. Her mother used the food from the mess to prepare a delicious holiday dinner. "We had ourselves a Christmas dinner and it was absolutely tops," Vernon said. "Little Nicole was beside herself. She had never had a doll before." The little girl's joy distracted the soldiers from the war which still had many horrors in store. A few months later, Vernon Alexander would witness the liberation of concentration camps. After the war, the images of stacks of emaciated corpses would often haunt him, but he cherished the memory of Nicole's first Christmas.[16]

Italian front

At the front in Italy, the Allied advance was held up by heavy snowfall on Christmas Day.[17] Rome had been liberated on June 4, 1944, by the Americans. In the city on December 24, the Pope, in his Christmas speech, advocated democracy and unity among all nations. He called for punishment of the aggressor within the framework of justice. For the first time since the year 800, civilians were admitted to the Christmas celebration in the basilica of St. Peter, where the façade could be illuminated again since the blackout had been lifted. With 75,000 visitors, including many military, the space was so overcrowded that some soldiers climbed onto confessional boxes to be able to watch the service.[18] Members of the Swiss Guard sang "Silent Night" in German.[19]

Allied soldiers during the Christmas celebration in the basilica of St. Peter. (Source: Life Magazine)

Allied soldiers during the Christmas celebration in the basilica of St. Peter. (Source: Life Magazine)

A little less than 250 miles northeast of the Italian capital in the picturesque Tuscany village of Barga, a platoon of some 60 soldiers celebrated Christmas with the civilian population. They were members of the 92nd Infantry Division, a segregated unit of African-American soldiers, also known as the Buffalo soldiers after the image of a buffalo on their divisional badges. On Christmas Eve, they distributed a truck load of various food stuffs, including chocolate and cheese. "We had never seen so much food," Irma Biondi – at the time 17 years of age – recalled. "They were wonderful, so nice to us. My little brother followed them like shadows."

Something like four or five soldiers were invited to a Christmas dinner by the family of the then 12-year-old Tullio Bertini. He and his parents had been born in the U.S. and were visiting Italy, but due to the outbreak of war they had not been able to return. Because of their mutual nationality, the soldiers felt at home with the Bertinis. As mother Bertini and a neighbor prepared dinner, the soldiers had brought a number of records with American dance music and a record player. "We had the dinner," Tullio recalled; "the soldiers mellowed by drinking wine, played music, danced with my mother. ... I thought it seemed the soldiers felt like they were in America, and I also think that my father and mother felt the same way, perhaps thinking that soon we would go back to the United States. The color of their skin did not come into focus. I thought they were Allied soldiers who had come to help get the Italians out of the WW II mess."

The pleasant evening was disrupted because German and Italian soldiers – fighting for Mussolini's puppet government and dressed in civilian clothes – infiltrated Barga and surrounding villages. The next day, a German-Italian offensive was launched during which some 40 African-Americans were killed. Barga was captured by the enemy but was recaptured by the Allies just a week later.[20]

Part of a Christmas card GI's could send in 1944 to their friends and family overseas.

Part of a Christmas card GI's could send in 1944 to their friends and family overseas.This Christmas, journalist Walter Cronkite was busier than during the previous two. Shortly after the start of the Ardennes offensive he was called to Paris to help out in the busy office of the United Press. Although he had been looking forward to a holiday celebration in the French capital, he had left for the front on Christmas Eve. Despite the cold, he was dressed in his normal clothing. Other items – long Johns, boots, gloves and a leather coat – he could not obtain before January 3rd, 1945. He worked for four days nonstop, but he judged he had little success as there were other journalists present who were better than himself. To his regret, it was only on December 27 that he managed to write a letter to his wife, telling her he had had an "awfully lonely Christmas – the worst ever, I think. I must admit that the surroundings weren't too unpleasant, but the fact that I was alone again without you made it almost unbearable." He spent Christmas Day in the city of Luxembourg which he described as "just as lovely as the post cards." At night he had a turkey dinner, along with Ernest Hemingway, Martha Gellhorn and other journalists. "We had some eggnog and everyone else, except old hard-working Cronkite, who had a fistful of mediocre stories to do, got pretty well pied. I had a few drinks and filed my last story about midnight after which I was so tired I just collapsed into bed."[1]

Tragedy with the Léopoldville

Walter Cronkite and his colleagues in Luxembourg had no idea that on Christmas Eve, a tragedy unfolded off the Normandy coast that would be kept under lock and key by the American army until 1959. The disaster took place in the English Channel where the Belgian troop transport vessel Léopoldville was on its way from Southampton in Great Britain to the European continent. The ship carried 2,223 American soldiers of the 66th Infantry Division who were to strengthen the forces in the Ardennes. The steamer, built in 1929, had been used for luxury cruises before the war, but nothing of that could be seen. Anything considered superfluous was removed in order to carry more passengers. Nevertheless, the vessel with 2,223 soldiers and a crew of 237 was overcrowded,[2] especially in the hold where soldiers made the journey, lying in hammocks and sitting at picnic tables in the passageways. "The stench aboard was really intense," passenger Vincent Codianni recalls. "Down below we were packed like sardines in a tin."[3] Far away from home on Christmas Eve, in heavy seas en route to a war zone, the spirit aboard was tense and depressed. If it wasn't fear or nostalgia the men felt, it was sea sickness. In these circumstances the trip was far from pleasant, but it would get much worse.

Somewhere near the Belgian vessel, the German U-486, commanded by Kapitän Gerhard Meyer, was lying in wait for prey. Aboard, the U-boat’s cook had made all preparations for Christmas. "He had baked a pie for everyone," according to a crew member. "The cream had been whipped. ... We had good food. We were ready for Christmas."[4] Suddenly all men were called to their battle stations. A convoy, including the Léopoldville, was spotted. Sinking an Allied ship justified postponing the Christmas celebration. Aboard the Belgian vessel, there was hardly any Christmas spirit. Despite the cold, some 20 soldiers had opted to leave the hold to sing Christmas carols in the fresh air on deck. To avoid being spotted by the enemy the vessel was darkened. The lights of Cherbourg, the ship's destination, were blinking in the distance, making the men feel at ease now that the journey would soon be over.[5] Suddenly, passengers and crew were shocked by a massive bang. In the hold, men were flung from their hammocks, and the crew called to them in Flemish to come up on deck.[6] Meanwhile, the U-boat that had fired the torpedo which struck the Léopoldville amidships descended to the seabed where she remained unseen and safe from depth charges.

As the freezing sea water rushed in below deck, everything that could go wrong did go wrong aboard the vessel. Panic broke out and the men had to struggle to get out of the ship's hold. Once on deck, they made the terrible discovery that the crew had already abandoned ship with all of the lifeboats, of which far too few had been aboard. Swimming vests were not available in sufficient numbers and safety instructions had not been given.[7] "I heard all kinds of yelling," Ed Phillips later declared about the situation on board. "I heard many boys calling for their mother. I did so too because the one person I really cared about was my mother."[8] Some men plunged into the freezing water while others jumped aboard the H.M.S. Brilliant, one of the escorts which had come alongside the Léopoldville. Hank Anderson, who had directed the singing of the Christmas carols on deck, watched some men stiffen at the prospect of having to jump. "These guys were paralyzed. They just would not jump. And they had seen some jump, and not made it. So it was quite a jump across. And I remember getting over there and sliding across what little deck there was, slammed into the bulwark that was there; staggered back up to the rail. And the sight that I had made it enabled them then to start jumping." He was safe but others misjudged their jump, landed between the vessels and were crushed.[9]

The Léopoldville sank around 20:45. Some 500 men had managed to board H.M.S. Brilliant safely while others still floated in the water. One of them was Ed Phillips who had to beat off several men to prevent him from going under. He was to be picked up by one of the vessels that had come to the rescue from Cherbourg, a mere 6.5 miles away.[10] Through miscommunication, the rescue operation had gotten under way far too late, resulting in numerous unnecessary victims.

Hank Anderson, who attributed his survival partly to the fact that he had left the hold to sing Christmas carols, told how he and the other survivors were taken care of in Cherbourg by black soldiers. "They surrounded us and sang Christmas carols. And I, I was so stunned."[11] A total of nearly 800 Americans would lose their lives either from drowning aboard the vessel, from hypothermia or from injuries sustained after they had jumped overboard. Captain Charles Limbor went down with his vessel too. A Belgian crew member and three Congolese also lost their lives.[12] This was not only a personal tragedy for passengers, crew and their next of kin but also a painful loss for the American war effort, yearning for reinforcements to be deployed in the Ardennes. Many of the rescued men were no longer fit for duty but had to recuperate in French hospitals from hypothermia or injuries.

A GI opens the Christmas package received from his wife. His buddies share the treat. European Theater, 1944. (Source: U.S. Army)

A GI opens the Christmas package received from his wife. His buddies share the treat. European Theater, 1944. (Source: U.S. Army)Unaware of the sinking of the Léopoldville, American military personnel shared the festivities with civilians in various locations in Europe. In Savere in Alsace, liberated for the most part in November 1944 by American and French troops, Private First Class Peter Feyen played Santa Claus for 150 children, mostly orphans. Although he was in his usual battledress and he had a three-day stubble instead of a long white beard, the candy he distributed was no less tasty for the boys and girls who had not celebrated Christmas for four years. Men from his liaison unit with the air force had given the local youth their chocolate rations and candy from their Christmas parcels. In addition, they had brought toys from Paris and oranges from North Africa to hand out. "Some of the youngsters had never seen an orange before and weren't quite certain whether to eat the fruit or bounce it," reporter Seymour Korman wrote. The children experienced another first by watching a Mickey Mouse movie. The mayor of the village expressed his gratitude for what the Americans had done and added that the Germans had never made a gesture like that during the occupation.[13]

Oranges also played an important role in the recollections of Christmas 1944 of 1st Lieutenant Robert J. Fisher. Posted to the 544th Bomb Squadron, 384th Bomb Group, he was stationed at R.A.F. Grafton Underwood. He and his bombardier had been invited to Christmas dinner by an English family in their home in Northampton, 25 miles southeast of the base. As he did not want to come empty-handed, for a few days beforehand he and his mate each set aside the orange that came with their breakfast. Some of their friends donated their oranges too; so eventually they had collected some fifteen oranges as a hostess gift. When they handed the bag of oranges to their grateful hostess, she immediately put all but two or three of them into a beautiful bowl which she placed on the mantelpiece. She and her husband next peeled the oranges she had kept apart. "The lady then asked her husband to go get the neighborhood children and bring them over to the house," Fisher said years later. "When the children arrived, the wife and her husband gave each child a section or two to eat and let them smell and feel the peeling. We thought this a little strange and asked them why they did it that way. They explained that they just had to share with the neighborhood children because most of them had never even seen an orange before, let alone tasted one!" Fisher was happy his present had been received so well. He was pleased "to witness an outstanding example of the true Christmas spirit. I will never forget Christmas of 1944."[14]

First Christmas

In Paris, the Americans distributed champagne and cognac among the citizens. In their haste to leave town, the Germans had left thousands of cases of these beverages behind. For many of the youngest children in France this was the first time they celebrated Christmas after an occupation of four years. Over those years, their parents had had neither opportunity nor means to celebrate Christmas.[15]

Nicole, about eight years old, did not know what Christmas was all about either. She was the daughter of the resistance couple with whom 20-year-old soldier Vernon Alexander from Arkansas and his mate Paul had moved in. Alexander was a machine gunner in the 2nd Battalion, 411th Regiment. In the French village where his unit had been quartered he had selected the small family house as their shelter because it had a large bay window which offered a clear view of any Germans who might approach. Communication between the French and the Americans proceeded laboriously as they did not speak each other's language. The Frenchman, Nicolas, was recuperating from a groin injury he had sustained from an exploding grenade, and his wife Lucy was afraid of what might still be in store for her family. For yet another year, a somber Christmas awaited their little daughter, but the Americans refused to let that happen. "She needed an American Christmas," Vernon stated years later.

After Nicole had tasted chocolate for the first time thanks to the Americans, Vernon and Paul now went out of their way to let her celebrate a real Christmas. She had not experienced this before or she could not remember it. They left the safety of the village to cut down a tree which they decorated with garlands made with wrapping paper from parcels from the USA. In their camp they found two dolls which they wrapped up for the girl. For Nicole's father, who was risking his life sheltering Americans, they found a box of cigars and tobacco. While Paul distracted the mess sergeant, Vernon stole fried ham, flour, sugar and some fruit from the mess tent. They smuggled the food and the Christmas tree into the home of the French family.

The next morning, about a week before Christmas, when Nicole saw the tree with the presents under it, she shrieked with joy. Her mother used the food from the mess to prepare a delicious holiday dinner. "We had ourselves a Christmas dinner and it was absolutely tops," Vernon said. "Little Nicole was beside herself. She had never had a doll before." The little girl's joy distracted the soldiers from the war which still had many horrors in store. A few months later, Vernon Alexander would witness the liberation of concentration camps. After the war, the images of stacks of emaciated corpses would often haunt him, but he cherished the memory of Nicole's first Christmas.[16]

Italian front

At the front in Italy, the Allied advance was held up by heavy snowfall on Christmas Day.[17] Rome had been liberated on June 4, 1944, by the Americans. In the city on December 24, the Pope, in his Christmas speech, advocated democracy and unity among all nations. He called for punishment of the aggressor within the framework of justice. For the first time since the year 800, civilians were admitted to the Christmas celebration in the basilica of St. Peter, where the façade could be illuminated again since the blackout had been lifted. With 75,000 visitors, including many military, the space was so overcrowded that some soldiers climbed onto confessional boxes to be able to watch the service.[18] Members of the Swiss Guard sang "Silent Night" in German.[19]

Allied soldiers during the Christmas celebration in the basilica of St. Peter. (Source: Life Magazine)

Allied soldiers during the Christmas celebration in the basilica of St. Peter. (Source: Life Magazine)A little less than 250 miles northeast of the Italian capital in the picturesque Tuscany village of Barga, a platoon of some 60 soldiers celebrated Christmas with the civilian population. They were members of the 92nd Infantry Division, a segregated unit of African-American soldiers, also known as the Buffalo soldiers after the image of a buffalo on their divisional badges. On Christmas Eve, they distributed a truck load of various food stuffs, including chocolate and cheese. "We had never seen so much food," Irma Biondi – at the time 17 years of age – recalled. "They were wonderful, so nice to us. My little brother followed them like shadows."

Something like four or five soldiers were invited to a Christmas dinner by the family of the then 12-year-old Tullio Bertini. He and his parents had been born in the U.S. and were visiting Italy, but due to the outbreak of war they had not been able to return. Because of their mutual nationality, the soldiers felt at home with the Bertinis. As mother Bertini and a neighbor prepared dinner, the soldiers had brought a number of records with American dance music and a record player. "We had the dinner," Tullio recalled; "the soldiers mellowed by drinking wine, played music, danced with my mother. ... I thought it seemed the soldiers felt like they were in America, and I also think that my father and mother felt the same way, perhaps thinking that soon we would go back to the United States. The color of their skin did not come into focus. I thought they were Allied soldiers who had come to help get the Italians out of the WW II mess."

The pleasant evening was disrupted because German and Italian soldiers – fighting for Mussolini's puppet government and dressed in civilian clothes – infiltrated Barga and surrounding villages. The next day, a German-Italian offensive was launched during which some 40 African-Americans were killed. Barga was captured by the enemy but was recaptured by the Allies just a week later.[20]

- Christmas under Fire, 1944

- The Last Christmas of World War II

- ISBN: 9781087410616

- More information about this book

Notes

- Cronkite IV, W. & Isserman, M., Cronkite's War: His World War II Letters Home, pp. 267-269.

- Weintraub, S, 11 Days in December, p. 142; Ambrose, S.E., Citizen Soldiers, pp. 273-273.

- Kerst aan het front, EO Tweede Wereldoorlog documentaires, 2005.

- Kerst aan het front, EO Tweede Wereldoorlog documentaires, 2005.

- ‘Minn. Church Recalls How Christmas Carols Saved Some U.S. Lives in World War II’, PBS Newshour, 23 Dec. 2011.

- Weintraub, S, 11 Days in December, p. 142.

- Ambrose, S.E., Citizen Soldiers, pp. 273-273.

- Kerst aan het front, EO Tweede Wereldoorlog documentaires, 2005.

- ‘Minn. Church Recalls How Christmas Carols Saved Some U.S. Lives in World War II’, PBS Newshour, 23 Dec. 2011.

- Kerst aan het front, EO Tweede Wereldoorlog documentaires, 2005.

- ‘Minn. Church Recalls How Christmas Carols Saved Some U.S. Lives in World War II’, PBS Newshour, 23 Dec. 2011.

- Allen, T., ‘The Sinking of SS Leopoldville’, 14 Apr. 2000, Uboat.net.

- Korman, S., ‘Chicago Santas give Party for Tiny Alsatians’, Chicago Tribune, 24 Dec. 1944.

- Fisher, R.J., ‘A Gift of Oranges’, America in WWII, Dec. 2010.

- Bruyere, A., ‘Many Children See First Joyful Yule’, Chicago Tribune, 25 Dec. 1944.

- Beilue, J.M., ‘World War II soldier brought American Christmas to French child’, Amarillo Globe-News, 20 Jul. 206.

- ‘White Christmas Slows up Action on Front in Italy’, Chicago Tribune, 26 Dec. 1944.

- ‘Papal Christmas’, Life Magazine, 15 Jan. 1945.

- ‘Pope Opposes Lasting Burden for War Losers’, Chicago Tribune, 25 Dec. 1944.

- Moore, C.P., Fighting for America, pp. 266-267.

Used source(s)

- Source: Kevin Prenger

- Published on: 14-12-2020 07:00:00

Related news

- 12-'23: Merry Christmas and a prosperous 2024

- 12-'21: Candles on War Graves

- 12-'21: World War 2 Youtube Series - How Hitler, Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin Spent Christmas

- 12-'20: Photo report Candles on Airborne War Cemetery Airborne Cemetery Oosterbeek

- 12-'20: Christmas during the Dutch winter famine of 1944

Latest news

- 16-02: Armin T. Wegner and his letter to Hitler

- 14-02: The hugely popular ‘Standing with Giants’ installation returns to the British Normandy Memorial

- 27-01: Russia focuses on Soviet victims of WW2 as officials not invited to Auschwitz ceremony

- 27-01: Oswald Kaduk, ‘Papa Kaduk’ or a monster?

- 12-'24: Christmas and New Year message from our volunteers

- 11-'24: New book: Righteous Behind Barbed Wire

- 11-'24: Postal artifacts provide a vibrant testament to the experiences of the Dutch people during WWII

- 10-'24: DigitalBattlefieldTours unlocks military tactics to a wide audience

- 10-'24: Lily Ebert, Holocaust Survivor, Author and TikTok Star, Dies at 100

- 10-'24: Commemoration 7th Battalion the Hampshire regiment