Kriegsweihnacht 1944, Christmas and Nazi propaganda

In 1944, Christmas was celebrated for the sixth time since the Second World War had broken out on September 1, 1939. Men who often shared the same religious background fought each other to the death in sharp contrast with the old Christmas message of Peace on Earth. Christmas under Fire, 1944 tells about this last war time Christmas. Below an excerpt from this book. This part is about how Christmas was used in Nazi propaganda.

Soldiers of the Volkssturm celebrate Christmas 1944 in a bunker in Eastern Prussia. On the table mail from the home front. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J28377 / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Soldiers of the Volkssturm celebrate Christmas 1944 in a bunker in Eastern Prussia. On the table mail from the home front. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J28377 / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

On Christmas Eve in a ward in a German hospital, an Oberleutnant lay motionless in bed. It was warm and quiet in the room where he was being treated for the severe injuries he had sustained on the Murmansk front. As he lay there in the corner near the stove, his head on a white pillow, it looked as if he were already dead. His eyes in a pale face were shut, and life seemed to be slipping away from him. All of a sudden, the door of the room was carefully opened and the dark room was lit by the cheerfully shimmering candles in a small fir tree. The soft sounds of German Christmas carols sung by children came closer and closer. As if by miracle, the eyes of the injured soldier opened. Laboriously, he raised himself to see where the light and the singing were coming from. While staring at the lights in the tree, his thoughts went back to past Christmas Days at home. A little smile appeared on his face. "He wants to live," so the story continues, "to live for the Heimat (fatherland) so far away but never so close as in this fateful moment, by the light of the Christmas tree. … And he feels joyous and happy: in this holy moment his fate returns from the frontier of death to within range of life itself. He will be cured."[1]

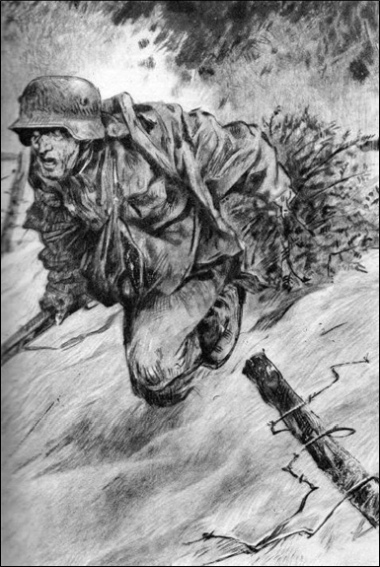

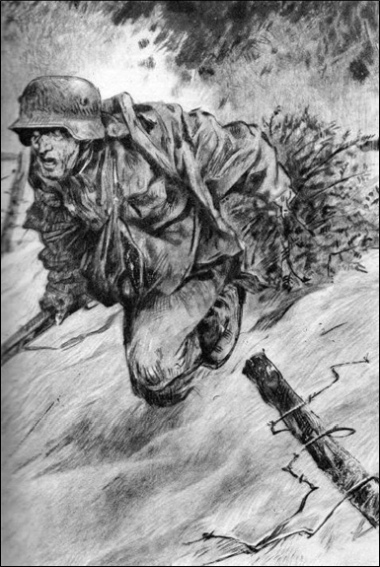

This story about a miraculous healing by the light of a Christmas tree was published in 1944 in the propaganda bulletin "Deutsche Kriegsweihnacht" (German War Christmas). Starting in 1941, each year prior to the Christmas holidays, the department of culture of the propaganda office of the NSDAP (National Socialist German Workers' Party) issued a compilation of Christmas stories for adults and children, this one being the last. The 1944 issue contained Christmas stories from the front during World War I, such as one about a soldier in France who, while on patrol close to enemy lines, risked his life while fetching a Christmas tree in order to celebrate Christmas. Furthermore, it contained letters to and from the front, poems and folk songs, all of course along the lines of the Nazi Christmas celebration. For the children, it contained fairy tales of Snow White and Mother Holle by the Grimm brothers.

A German soldier risks his life taking a Christmas tree to his own lines. Image from Deutsche Kriegsweihnacht. (Collection author)

A German soldier risks his life taking a Christmas tree to his own lines. Image from Deutsche Kriegsweihnacht. (Collection author)

Speeches by the master of propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, could not be left out of course. A posthumously published contribution of an ode to the German Christmas celebration was included: National Socialist writer and poet Kurt Eggers died in 1943 at the Eastern front serving with the Waffen-SS. He argued Christmas was not about "giving love" and "legends from the far away Jewish land" but about "freedom, honor and justice." He described the Christmas tree as the symbol of the "grandeur of the struggling and defiant life that in danger and in need holds out against any fearsome and difficult situation." According to him, Christmas became "the celebration of victory and the required willingness to fight. ... We therefore do not celebrate our Weihnachtsfest in the sentimental mood, contained in so many strange Christmas carols, but in the hard and inflexible knowledge that we, as the perennial torch bearers, are destined to carry the light of freedom in the world."[2]

Despite Eggers' jubilant words, the tone of the Nazi Christmas book was gloomier than before, as the circumstances at the fronts did not justify any festivities. Yearning for the Heimat had become a more important theme than the victories and the expansion of the Third Reich. This was for instance the case in the story about a Volksdeutsche (someone of German ancestry living outside the German borders) farmer who was traveling by horse-drawn cart from Russia in wintry conditions with his wife, children and grandfather in order to settle in Germany. The return to Germany of people of German ancestry was an idea the Nazis propagated with the slogan "Heim ins Reich" (Back home to the Reich). In the story, the farmer's wife was pregnant with their fifth child and the old man hoped to reach German soil so he could die there. Straw and blankets in the cart protected the passengers from the cold.

On Christmas Eve they had reached a forest on the farthest frontier of the Reich where, in the winter night, their child was born. Women from other families, who were traveling with them to the Reich, had lighted a fire in the forest and had prepared something warm for the mother. "It was a miracle," they said. "Entirely healthy and well built, it had come into this world in the middle of the eastern winter. Yes, yes, the sturdy farmers' blood." The child was swaddled and laid down in the cart between the blankets. "And as the wind softly stroked the tree tops," the story continues, "it was as if they sang a lullaby for the baby."

Suddenly the woman saw her child "look out with its eyes wide open. Then the mother saw it too: a miracle had happened. A bright light radiated from the fir tree standing high and tall in the night sky. A light like stardust lay over all its branches! Tall and festive, the shining tree stood in the winter night and it was more beautiful to see than all Christmas trees in the world." The next morning, people from the other carts came to look at the child who had been born during the "great exodus." The writer's source of inspiration needs no further explanation. "The first child had been born in the Heimat – now new life began for all."[3]

In another Nazi publication, the bulletin "Die Neue Gemeinschaft" (The New Society) issued by the department of ceremonies and holidays of the NSDAP, a speech had been printed prior to the holidays that party leaders could deliver at Christmas to the injured in military hospitals. It was written by Nazi author and poet Thilo Scheller who had found inspiration in a poem by 19th century poet Wilhelm Weber, "Es wächst viel Brot in der Winternacht" (Much grain grows during winter's night), which was the title of the speech as well. The message of the poem was that beneath the snow of winter, seeds for grain lie dormant in expectation of spring, a prediction it was hoped, would be applicable to the Third Reich as well. The speech also stated: "Even the most hard-boiled soldier, the most dashing dare-devil, is not embarrassed to turn soft for an evening – when it is Christmas in Germany, and wherever there are Germans."

Christmas brought back memories of old Christmas carols, of the lights in the Christmas tree and of mothers and girlfriends. Injured or sick soldiers should be told that their hearts were allowed to be home, but they should not be homesick. The people's community "that our Führer Adolf Hitler has given us, will not forget those who cannot celebrate Christmas with their loved ones." They should derive hope from the presence of the nurses, whose names like Inge or Gertrud would feel dependable. Christmas was not to be celebrated too exuberantly at a time "when all the strengths of the front and homeland are needed for the war effort, when our comrades in the field are surrounded by filth and hardly know where to find a small tree and a miserable Christmas candle."

"The enemy has laid in ruins many treasured buildings, many quiet corners, many familiar dwellings where shining Christmas trees stood year after year," the speech continued. "Yet he cannot destroy those fir trees in the forest, rooted in German earth, nor can he destroy our hearts that are even more firmly rooted in the German people. Even in the ruins of cities destroyed by Negro pilots who have not the faintest inkling of what a German Christmas means." Here, reference is made to the attempt of July 20th that year when "providence preserved the Führer because it needs him for the future of our people, also so that our children will be able to celebrate Christmas in peace and joy." The guests to be invited were "all our dead comrades from all the battlefields of Europe. … They should be with us in spirit, not as pale ghosts, but in the fullness of their youth. That should teach us that the morale in the homeland is worthy of our soldiers at the front!"

The text ended as follows: "My dear comrades, war has been called the father of all things, but it also gives depth and meaning to the most motherly of all festivals, one that gives our people the strength to end this war with victory, to banish everything superficial and false and foreign. The grain will grow in stillness from the depths, producing the bread that we, God grant, will eat in peace."[4]

With the publication of "Deutsche Kriegsweihnacht" and the mandatory speech to injured and sick soldiers, the Nazi regime showed in 1944 that it still wanted to exert influence on the way the Germans celebrated Christmas, as it had in the 1930s. In order not to endanger the relationship with Christians during the war, the Christian Christmas celebration was not directly attacked. Hence in the Wehrmacht, chaplains were not prevented from conducting religious Christmas celebrations. Attempts were still being made, though, to introduce new Christmas practices that matched the Nazi world view. An increasingly important emphasis was placed at Christmastime on reverence for the soldiers who had died for the Fatherland, as had been the case during the previous world war. It was an attempt to lend a positive sense to the grieving of many German families over the loss of a father, husband or son.

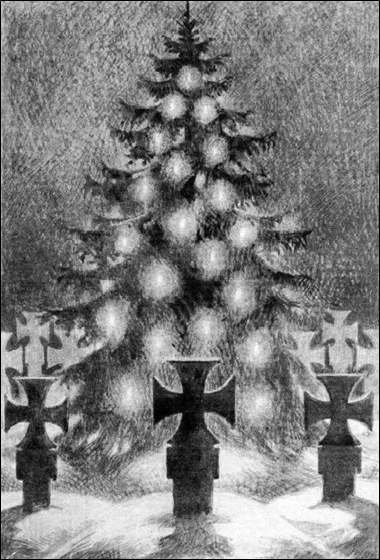

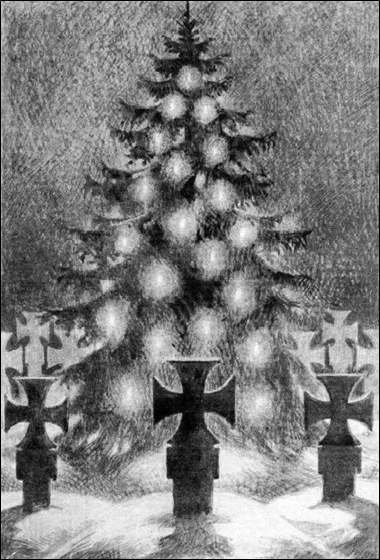

Around Christmas a cult of death was promoted with stories, songs, poems and drawings. The Nazi Christmas book of 1944, for instance, showed a drawing of an illuminated Christmas tree surrounded by soldiers' graves marked by Iron Crosses.[5] A much published expression of this reverence for death was the poem "Der toten Soldaten Heimkehr" (the return of the dead soldiers) by Thilo Schiller. "And when the candles burn down on the tree of light", one of the lines read, "the dead soldier places his earth-encrusted hand lightly on each of the children's young heads. We died for you, for we believed in Germany."[6]The "Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Yet to Come" were amateurs in comparison to this Christmas horror. The poet also thought of phrases the children had to recite on Christmas when lighting the candles of an Advent wreath one by one and respectively naming the mother, the poor, the dead and the Führer.[7]

Christmas tree on German war graves. Image from Deutsche Kriegsweihnacht. (Collection author)

Christmas tree on German war graves. Image from Deutsche Kriegsweihnacht. (Collection author)

Nazi propaganda makers encouraged mothers and widows to decorate a picture of their son or husband, fallen at the front, with a fir branch, to lay a place at table for him during the Christmas dinner and to light a red candle in the Christmas tree for him. They also wanted to relocate part of the Christmas celebration to cemeteries of fallen soldiers and war memorial sites. Placing candles or even small Christmas trees on graves was encouraged although it must be noted here that lighting candles on graves was a tradition that existed before 1933 so this was no invention of the Nazis at all. How many Germans followed these instructions is hard to determine, although the shortage of candles surely did not help one bit.[8]

Soldiers of the Volkssturm celebrate Christmas 1944 in a bunker in Eastern Prussia. On the table mail from the home front. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J28377 / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Soldiers of the Volkssturm celebrate Christmas 1944 in a bunker in Eastern Prussia. On the table mail from the home front. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J28377 / CC-BY-SA 3.0)On Christmas Eve in a ward in a German hospital, an Oberleutnant lay motionless in bed. It was warm and quiet in the room where he was being treated for the severe injuries he had sustained on the Murmansk front. As he lay there in the corner near the stove, his head on a white pillow, it looked as if he were already dead. His eyes in a pale face were shut, and life seemed to be slipping away from him. All of a sudden, the door of the room was carefully opened and the dark room was lit by the cheerfully shimmering candles in a small fir tree. The soft sounds of German Christmas carols sung by children came closer and closer. As if by miracle, the eyes of the injured soldier opened. Laboriously, he raised himself to see where the light and the singing were coming from. While staring at the lights in the tree, his thoughts went back to past Christmas Days at home. A little smile appeared on his face. "He wants to live," so the story continues, "to live for the Heimat (fatherland) so far away but never so close as in this fateful moment, by the light of the Christmas tree. … And he feels joyous and happy: in this holy moment his fate returns from the frontier of death to within range of life itself. He will be cured."[1]

This story about a miraculous healing by the light of a Christmas tree was published in 1944 in the propaganda bulletin "Deutsche Kriegsweihnacht" (German War Christmas). Starting in 1941, each year prior to the Christmas holidays, the department of culture of the propaganda office of the NSDAP (National Socialist German Workers' Party) issued a compilation of Christmas stories for adults and children, this one being the last. The 1944 issue contained Christmas stories from the front during World War I, such as one about a soldier in France who, while on patrol close to enemy lines, risked his life while fetching a Christmas tree in order to celebrate Christmas. Furthermore, it contained letters to and from the front, poems and folk songs, all of course along the lines of the Nazi Christmas celebration. For the children, it contained fairy tales of Snow White and Mother Holle by the Grimm brothers.

A German soldier risks his life taking a Christmas tree to his own lines. Image from Deutsche Kriegsweihnacht. (Collection author)

A German soldier risks his life taking a Christmas tree to his own lines. Image from Deutsche Kriegsweihnacht. (Collection author)Speeches by the master of propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, could not be left out of course. A posthumously published contribution of an ode to the German Christmas celebration was included: National Socialist writer and poet Kurt Eggers died in 1943 at the Eastern front serving with the Waffen-SS. He argued Christmas was not about "giving love" and "legends from the far away Jewish land" but about "freedom, honor and justice." He described the Christmas tree as the symbol of the "grandeur of the struggling and defiant life that in danger and in need holds out against any fearsome and difficult situation." According to him, Christmas became "the celebration of victory and the required willingness to fight. ... We therefore do not celebrate our Weihnachtsfest in the sentimental mood, contained in so many strange Christmas carols, but in the hard and inflexible knowledge that we, as the perennial torch bearers, are destined to carry the light of freedom in the world."[2]

Despite Eggers' jubilant words, the tone of the Nazi Christmas book was gloomier than before, as the circumstances at the fronts did not justify any festivities. Yearning for the Heimat had become a more important theme than the victories and the expansion of the Third Reich. This was for instance the case in the story about a Volksdeutsche (someone of German ancestry living outside the German borders) farmer who was traveling by horse-drawn cart from Russia in wintry conditions with his wife, children and grandfather in order to settle in Germany. The return to Germany of people of German ancestry was an idea the Nazis propagated with the slogan "Heim ins Reich" (Back home to the Reich). In the story, the farmer's wife was pregnant with their fifth child and the old man hoped to reach German soil so he could die there. Straw and blankets in the cart protected the passengers from the cold.

On Christmas Eve they had reached a forest on the farthest frontier of the Reich where, in the winter night, their child was born. Women from other families, who were traveling with them to the Reich, had lighted a fire in the forest and had prepared something warm for the mother. "It was a miracle," they said. "Entirely healthy and well built, it had come into this world in the middle of the eastern winter. Yes, yes, the sturdy farmers' blood." The child was swaddled and laid down in the cart between the blankets. "And as the wind softly stroked the tree tops," the story continues, "it was as if they sang a lullaby for the baby."

Suddenly the woman saw her child "look out with its eyes wide open. Then the mother saw it too: a miracle had happened. A bright light radiated from the fir tree standing high and tall in the night sky. A light like stardust lay over all its branches! Tall and festive, the shining tree stood in the winter night and it was more beautiful to see than all Christmas trees in the world." The next morning, people from the other carts came to look at the child who had been born during the "great exodus." The writer's source of inspiration needs no further explanation. "The first child had been born in the Heimat – now new life began for all."[3]

In another Nazi publication, the bulletin "Die Neue Gemeinschaft" (The New Society) issued by the department of ceremonies and holidays of the NSDAP, a speech had been printed prior to the holidays that party leaders could deliver at Christmas to the injured in military hospitals. It was written by Nazi author and poet Thilo Scheller who had found inspiration in a poem by 19th century poet Wilhelm Weber, "Es wächst viel Brot in der Winternacht" (Much grain grows during winter's night), which was the title of the speech as well. The message of the poem was that beneath the snow of winter, seeds for grain lie dormant in expectation of spring, a prediction it was hoped, would be applicable to the Third Reich as well. The speech also stated: "Even the most hard-boiled soldier, the most dashing dare-devil, is not embarrassed to turn soft for an evening – when it is Christmas in Germany, and wherever there are Germans."

Christmas brought back memories of old Christmas carols, of the lights in the Christmas tree and of mothers and girlfriends. Injured or sick soldiers should be told that their hearts were allowed to be home, but they should not be homesick. The people's community "that our Führer Adolf Hitler has given us, will not forget those who cannot celebrate Christmas with their loved ones." They should derive hope from the presence of the nurses, whose names like Inge or Gertrud would feel dependable. Christmas was not to be celebrated too exuberantly at a time "when all the strengths of the front and homeland are needed for the war effort, when our comrades in the field are surrounded by filth and hardly know where to find a small tree and a miserable Christmas candle."

"The enemy has laid in ruins many treasured buildings, many quiet corners, many familiar dwellings where shining Christmas trees stood year after year," the speech continued. "Yet he cannot destroy those fir trees in the forest, rooted in German earth, nor can he destroy our hearts that are even more firmly rooted in the German people. Even in the ruins of cities destroyed by Negro pilots who have not the faintest inkling of what a German Christmas means." Here, reference is made to the attempt of July 20th that year when "providence preserved the Führer because it needs him for the future of our people, also so that our children will be able to celebrate Christmas in peace and joy." The guests to be invited were "all our dead comrades from all the battlefields of Europe. … They should be with us in spirit, not as pale ghosts, but in the fullness of their youth. That should teach us that the morale in the homeland is worthy of our soldiers at the front!"

The text ended as follows: "My dear comrades, war has been called the father of all things, but it also gives depth and meaning to the most motherly of all festivals, one that gives our people the strength to end this war with victory, to banish everything superficial and false and foreign. The grain will grow in stillness from the depths, producing the bread that we, God grant, will eat in peace."[4]

With the publication of "Deutsche Kriegsweihnacht" and the mandatory speech to injured and sick soldiers, the Nazi regime showed in 1944 that it still wanted to exert influence on the way the Germans celebrated Christmas, as it had in the 1930s. In order not to endanger the relationship with Christians during the war, the Christian Christmas celebration was not directly attacked. Hence in the Wehrmacht, chaplains were not prevented from conducting religious Christmas celebrations. Attempts were still being made, though, to introduce new Christmas practices that matched the Nazi world view. An increasingly important emphasis was placed at Christmastime on reverence for the soldiers who had died for the Fatherland, as had been the case during the previous world war. It was an attempt to lend a positive sense to the grieving of many German families over the loss of a father, husband or son.

Around Christmas a cult of death was promoted with stories, songs, poems and drawings. The Nazi Christmas book of 1944, for instance, showed a drawing of an illuminated Christmas tree surrounded by soldiers' graves marked by Iron Crosses.[5] A much published expression of this reverence for death was the poem "Der toten Soldaten Heimkehr" (the return of the dead soldiers) by Thilo Schiller. "And when the candles burn down on the tree of light", one of the lines read, "the dead soldier places his earth-encrusted hand lightly on each of the children's young heads. We died for you, for we believed in Germany."[6]The "Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Yet to Come" were amateurs in comparison to this Christmas horror. The poet also thought of phrases the children had to recite on Christmas when lighting the candles of an Advent wreath one by one and respectively naming the mother, the poor, the dead and the Führer.[7]

Christmas tree on German war graves. Image from Deutsche Kriegsweihnacht. (Collection author)

Christmas tree on German war graves. Image from Deutsche Kriegsweihnacht. (Collection author)Nazi propaganda makers encouraged mothers and widows to decorate a picture of their son or husband, fallen at the front, with a fir branch, to lay a place at table for him during the Christmas dinner and to light a red candle in the Christmas tree for him. They also wanted to relocate part of the Christmas celebration to cemeteries of fallen soldiers and war memorial sites. Placing candles or even small Christmas trees on graves was encouraged although it must be noted here that lighting candles on graves was a tradition that existed before 1933 so this was no invention of the Nazis at all. How many Germans followed these instructions is hard to determine, although the shortage of candles surely did not help one bit.[8]

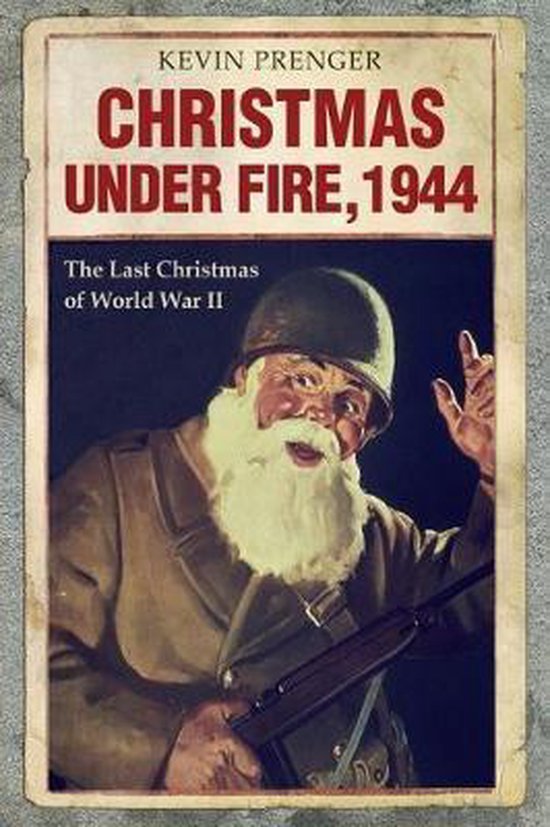

- Christmas under Fire, 1944

- The Last Christmas of World War II

- ISBN: 9781087410616

- More information about this book

Notes

- Liese, H. (ed.), Deutsche Kriegsweihnacht, pp. 106-108.

- Liese, H. (ed.), Deutsche Kriegsweihnacht, pp. 8-10.

- Liese, H. (ed.), Deutsche Kriegsweihnacht, pp. 125-127.

- Bytwerk, R., ‘Much Grain Grows during Winter’s Night...’, German Propaganda Archive Calvin College.

- Liese, H. (ed.), Deutsche Kriegsweihnacht, p. 190.

- Perry, J., ‘Nazifying Christmas: Political Culture and Popular Celebration in the Third Reich’, Central European History, Dec. 2005.

- Gajek, E., ‘Christmas under the Third Reich’, Anthropology today, nr. 6, 1990.

- Perry, J., Christmas in Germany, pp. 235-237; Gajek, E., ‘Christmas under the Third Reich’, Anthropology today, nr. 6, 1990.

Used source(s)

- Source: Christmas under Fire, 1944

- Published on: 07-12-2020 07:00:00

Related news

- 12-'23: Merry Christmas and a prosperous 2024

- 12-'21: Candles on War Graves

- 12-'21: World War 2 Youtube Series - How Hitler, Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin Spent Christmas

- 12-'20: Photo report Candles on Airborne War Cemetery Airborne Cemetery Oosterbeek

- 12-'20: Christmas during the Dutch winter famine of 1944

Latest news

- 12-04: Understanding the German side of the fighting in Normandy

- 03-03: A WWII helmet returns home 80 years after having been lost at Remagen Bridge, Germany

- 16-02: Armin T. Wegner and his letter to Hitler

- 14-02: The hugely popular ‘Standing with Giants’ installation returns to the British Normandy Memorial

- 27-01: Russia focuses on Soviet victims of WW2 as officials not invited to Auschwitz ceremony

- 27-01: Oswald Kaduk, ‘Papa Kaduk’ or a monster??

- 12-'24: Christmas and New Year message from our volunteers

- 11-'24: New book: Righteous Behind Barbed Wire

- 11-'24: Postal artifacts provide a vibrant testament to the experiences of the Dutch people during WWII

- 10-'24: DigitalBattlefieldTours unlocks military tactics to a wide audience