Christmas during the Dutch winter famine of 1944

In 1944, Christmas was celebrated for the sixth time since the Second World War had broken out on September 1, 1939. Men who often shared the same religious background fought each other to the death in sharp contrast with the old Christmas message of Peace on Earth. Christmas under Fire, 1944 tells about this last war time Christmas. Below an excerpt from this book. This part is about the Dutch winter famine of 1944.

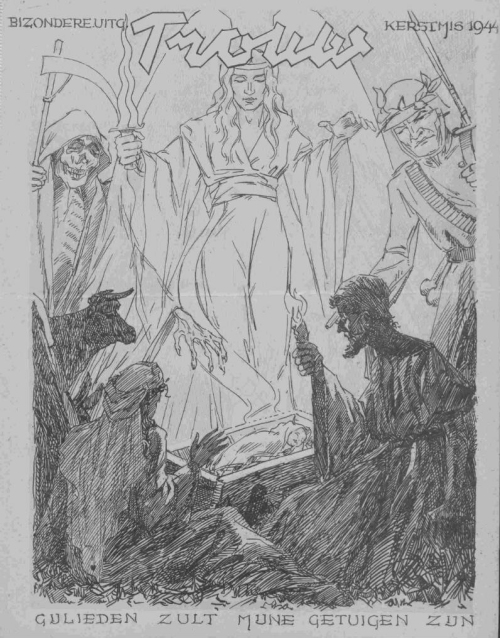

The front page of the Haarlem edition of the Christian resistance paper Trouw (Loyalty) of December 21st 1944. (Delpher)

The front page of the Haarlem edition of the Christian resistance paper Trouw (Loyalty) of December 21st 1944. (Delpher)

The relentless actions by the occupier against the resistance had become daily routine in 1944. In addition, in that year many men had been drafted for labor in Germany in connection with the Arbeitseinsatz (forced labor deployment). In particular though, it was the famine above all during the winter of 1944/1945 that caused much suffering. This was the result of the order by Reichskommissar (state commissioner) Arthur Seyss-Inquart to halt all inland shipping. His order was a reprisal against the general railway strike which had been ordered by the Dutch government on September 17, 1944, in support of Operation Market Garden and with which the Dutch complied on a large scale. As a result of Seyss-Inquart's order, the densely populated western part of the country (the Randstad, which included Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, and Utrecht) was cut off from food and fuel.

After the lifting of the blockade six weeks later, inland shipping was resumed with great difficulty. When canals and rivers as well as the IJsselmeer froze over in December, ship traffic was impossible until February. For the population in the Randstad, the consequences were severe. City-dwellers went en masse to the countryside to obtain food. In order to warm themselves in the harsh winter, people even used furniture as fuel. Owing to the scarce and unvaried foods on the one hand and the deteriorating hygienic situation on the other, conditions like hunger edema, tuberculosis and scabies erupted. Dysentery and diphtheria were rampant among children. No less than 200,000 people had to be treated in hospital for malnutrition. During the winter famine, an estimated 20,000 to 22,000 people died of inadequate nutrition, sickness and exhaustion.[1]

Dark, cold, and shortages – these words describe the Christmas celebration of many residents of the major cities in the west. In their apartment over Café De IJsbreker along the Amstel in Amsterdam, the Crone couple spent the Christmas holidays for the most part in bed as this was the only place in the house where it was warm. Fuel for the stove was barely available. When they got out of bed, they walked around in coats and hats. Light was provided by a few candles and a kerosene lantern as there was no electricity either. Likewise, food was scarce, and their Christmas dinner consisted of only winter carrots and nothing else. They had bought a little Christmas tree though. The couple still had some flour and butter in the house, but they had agreed to save it until New Year's Eve to bake some Dutch pancakes, which they did using a few pieces of wood and a make-shift stove.

For the Amsberg family, also living in Amsterdam, at Christmas there was little more than the smell of pancakes being baked by the neighbors across the street. The Amsbergs had hardly anything to eat themselves. Their daughter Kiki, four years of age at the time, could only recall after the war that she had shared a tin of sweetened condensed milk among the three of them as a Christmas dinner. She had lost her cat as well. According to her parents, the animal had been stolen. It’s very possible that her cat was not the only one that disappeared into some starving family’s cooking pot.[2]

In Scheveningen near The Hague, the Christmas atmosphere was hardly any better than in the capital. According to the fisherman Cor van Toorn, hardly anyone enjoyed Christmas. Without heating and by the light of a lone candle, after around 19:00 or 19:30 there was little else to do but go to bed. He knew it was December 25 but that was all there was to it. Since September, he was employed in the soup kitchen on the Van Alkemadelaan where food supplies had decreased considerably. In September, 20 packs of butter were added to the soup pots of 135 gallons; in December this had dropped to just one. With 10 crates of salad added, this mixture had to pass for vegetable soup.

Two days before Christmas he and a few others were dispatched with horse and carriage to get potatoes from the cellar of a government building on the Oostduinlaan. The whole floor was covered with them but most were rotten. Nevertheless, everything was taken. Then the good potatoes were selected and thrown into the peeling machine. These peeled potatoes were distributed as a supplement on the two Christmas days (in the Netherlands Christmas is celebrated on 25 and 26 December). Another addition to the Christmas ration was a small bowl of mashed potatoes and cabbage with a little bacon for everyone. The people who received this food, according to Cor, found this Christmas addition marvelous, but after Christmas they would have to make do again with gradually dwindling rations.[3]

In the home of Catholic politician P.J.M. Aalberse in The Hague, "only one room could be moderately heated and only for a few hours per day" in the period prior to Christmas because of the shortage of coal. He wondered if they could make it until Christmas with the dwindling coal supply. He wrote: "Sitting in the cold all the time with numb fingers and icy feet was even worse than being hungry." Many of his fellow citizens set off to gather wood to fuel their stoves. Every day he saw upper-class as well as lower-class people "carrying bundles of branches they had collected in the bushes. Often, entire trees were cut down." According to Aalberse, it was impossible to heat the house above 10°C on the Christmas holidays. There was no electricity either, and the only source of light in the Aalberse home was a few candles which had to be used sparingly, causing the family to sit in the dark at night for a long time. A good night's rest was a rarity as well because V-1s and V-2s were launched not far from the city, causing a lot of noise.

The news of the German breakthrough in the Ardennes had also reached the Netherlands, adding to the dejected mood of the Christmas days. "The hope of being finally liberated after five long years has been pushed back into the far distance again," Aalberse wrote in his diary. "Added to this was the dire situation in which we lived .... Potatoes, our main source of food, are now rationed to 1 kilo per person per week. The bread ration had already been reduced to 1500 grams per week. Vegetables have not been available for weeks. That is what we were facing. Each night, we went to bed hungry."

The food situation in the northern and eastern parts of the Netherlands was less dire than elsewhere because in those parts, farmers provided an acceptable supply of food. Unlike starving residents in the Randstad, the Aalberse family did not need to search for food in the holiday period the Aalberse family did not need to search for food in the holiday period as it was simply delivered to them. Friends from Zevenaar had sent them a large parcel that was delivered the Friday before Christmas. "So many delicious things in there," Aalberse enthusiastically entered in his diary. "A beautiful chunk of pork, three hard-boiled eggs, many legumes, powdered milk and so on and on. Yes, even an extravagant luxury for me, a bag of delicious pre-war tobacco!" He and his mother got tears in their eyes and danced around the table in enjoyment. After Christmas they received some more legumes and "two delicious mutton chops" from other friends outside The Hague. "So at Christmas we felt like kings," according to the author, and "we did not have to lie in bed yawning with an empty stomach."[4]

The front page of the Haarlem edition of the Christian resistance paper Trouw (Loyalty) of December 21st 1944. (Delpher)

The front page of the Haarlem edition of the Christian resistance paper Trouw (Loyalty) of December 21st 1944. (Delpher)The relentless actions by the occupier against the resistance had become daily routine in 1944. In addition, in that year many men had been drafted for labor in Germany in connection with the Arbeitseinsatz (forced labor deployment). In particular though, it was the famine above all during the winter of 1944/1945 that caused much suffering. This was the result of the order by Reichskommissar (state commissioner) Arthur Seyss-Inquart to halt all inland shipping. His order was a reprisal against the general railway strike which had been ordered by the Dutch government on September 17, 1944, in support of Operation Market Garden and with which the Dutch complied on a large scale. As a result of Seyss-Inquart's order, the densely populated western part of the country (the Randstad, which included Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, and Utrecht) was cut off from food and fuel.

After the lifting of the blockade six weeks later, inland shipping was resumed with great difficulty. When canals and rivers as well as the IJsselmeer froze over in December, ship traffic was impossible until February. For the population in the Randstad, the consequences were severe. City-dwellers went en masse to the countryside to obtain food. In order to warm themselves in the harsh winter, people even used furniture as fuel. Owing to the scarce and unvaried foods on the one hand and the deteriorating hygienic situation on the other, conditions like hunger edema, tuberculosis and scabies erupted. Dysentery and diphtheria were rampant among children. No less than 200,000 people had to be treated in hospital for malnutrition. During the winter famine, an estimated 20,000 to 22,000 people died of inadequate nutrition, sickness and exhaustion.[1]

Dark, cold, and shortages – these words describe the Christmas celebration of many residents of the major cities in the west. In their apartment over Café De IJsbreker along the Amstel in Amsterdam, the Crone couple spent the Christmas holidays for the most part in bed as this was the only place in the house where it was warm. Fuel for the stove was barely available. When they got out of bed, they walked around in coats and hats. Light was provided by a few candles and a kerosene lantern as there was no electricity either. Likewise, food was scarce, and their Christmas dinner consisted of only winter carrots and nothing else. They had bought a little Christmas tree though. The couple still had some flour and butter in the house, but they had agreed to save it until New Year's Eve to bake some Dutch pancakes, which they did using a few pieces of wood and a make-shift stove.

For the Amsberg family, also living in Amsterdam, at Christmas there was little more than the smell of pancakes being baked by the neighbors across the street. The Amsbergs had hardly anything to eat themselves. Their daughter Kiki, four years of age at the time, could only recall after the war that she had shared a tin of sweetened condensed milk among the three of them as a Christmas dinner. She had lost her cat as well. According to her parents, the animal had been stolen. It’s very possible that her cat was not the only one that disappeared into some starving family’s cooking pot.[2]

In Scheveningen near The Hague, the Christmas atmosphere was hardly any better than in the capital. According to the fisherman Cor van Toorn, hardly anyone enjoyed Christmas. Without heating and by the light of a lone candle, after around 19:00 or 19:30 there was little else to do but go to bed. He knew it was December 25 but that was all there was to it. Since September, he was employed in the soup kitchen on the Van Alkemadelaan where food supplies had decreased considerably. In September, 20 packs of butter were added to the soup pots of 135 gallons; in December this had dropped to just one. With 10 crates of salad added, this mixture had to pass for vegetable soup.

Two days before Christmas he and a few others were dispatched with horse and carriage to get potatoes from the cellar of a government building on the Oostduinlaan. The whole floor was covered with them but most were rotten. Nevertheless, everything was taken. Then the good potatoes were selected and thrown into the peeling machine. These peeled potatoes were distributed as a supplement on the two Christmas days (in the Netherlands Christmas is celebrated on 25 and 26 December). Another addition to the Christmas ration was a small bowl of mashed potatoes and cabbage with a little bacon for everyone. The people who received this food, according to Cor, found this Christmas addition marvelous, but after Christmas they would have to make do again with gradually dwindling rations.[3]

In the home of Catholic politician P.J.M. Aalberse in The Hague, "only one room could be moderately heated and only for a few hours per day" in the period prior to Christmas because of the shortage of coal. He wondered if they could make it until Christmas with the dwindling coal supply. He wrote: "Sitting in the cold all the time with numb fingers and icy feet was even worse than being hungry." Many of his fellow citizens set off to gather wood to fuel their stoves. Every day he saw upper-class as well as lower-class people "carrying bundles of branches they had collected in the bushes. Often, entire trees were cut down." According to Aalberse, it was impossible to heat the house above 10°C on the Christmas holidays. There was no electricity either, and the only source of light in the Aalberse home was a few candles which had to be used sparingly, causing the family to sit in the dark at night for a long time. A good night's rest was a rarity as well because V-1s and V-2s were launched not far from the city, causing a lot of noise.

The news of the German breakthrough in the Ardennes had also reached the Netherlands, adding to the dejected mood of the Christmas days. "The hope of being finally liberated after five long years has been pushed back into the far distance again," Aalberse wrote in his diary. "Added to this was the dire situation in which we lived .... Potatoes, our main source of food, are now rationed to 1 kilo per person per week. The bread ration had already been reduced to 1500 grams per week. Vegetables have not been available for weeks. That is what we were facing. Each night, we went to bed hungry."

The food situation in the northern and eastern parts of the Netherlands was less dire than elsewhere because in those parts, farmers provided an acceptable supply of food. Unlike starving residents in the Randstad, the Aalberse family did not need to search for food in the holiday period the Aalberse family did not need to search for food in the holiday period as it was simply delivered to them. Friends from Zevenaar had sent them a large parcel that was delivered the Friday before Christmas. "So many delicious things in there," Aalberse enthusiastically entered in his diary. "A beautiful chunk of pork, three hard-boiled eggs, many legumes, powdered milk and so on and on. Yes, even an extravagant luxury for me, a bag of delicious pre-war tobacco!" He and his mother got tears in their eyes and danced around the table in enjoyment. After Christmas they received some more legumes and "two delicious mutton chops" from other friends outside The Hague. "So at Christmas we felt like kings," according to the author, and "we did not have to lie in bed yawning with an empty stomach."[4]

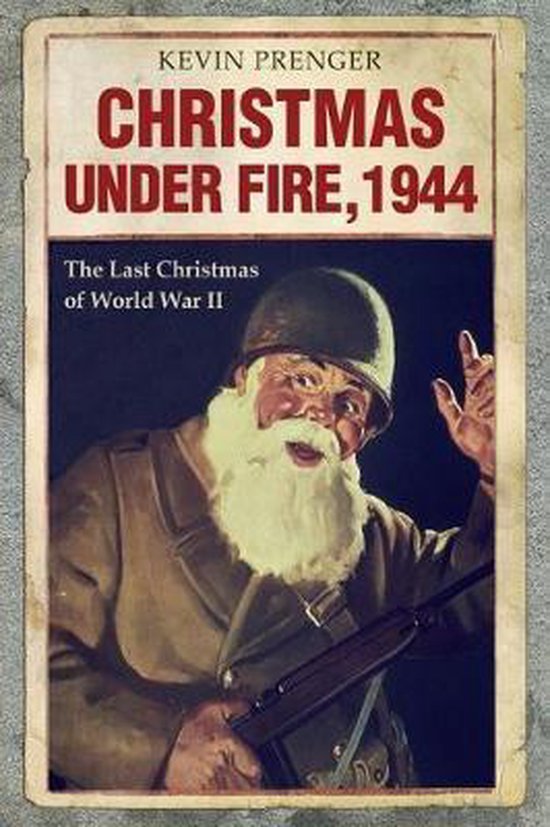

- Christmas under Fire, 1944

- The Last Christmas of World War II

- ISBN: 9781087410616

- More information about this book

Notes

- Kok, R. & Somers, E., Nederland en de Tweede Wereldoorlog, pp. 427-429.

- VPRO-radio Het Spoor Terug, ‘Kerst 1944’, 27 Dec. 1987.

- VPRO-radio Het Spoor Terug, ‘Kerst 1944’, 27 Dec. 1987.

- Aalberse, P.J.M., Dagboek XI: Begin november 1944 tot 7 augustus 1946, Huygens ING digitaal archief.

Used source(s)

- Source: Christmas under Fire, 1944

- Published on: 21-12-2020 07:00:00

Related news

- 12-'23: Merry Christmas and a prosperous 2024

- 12-'21: Candles on War Graves

- 12-'21: World War 2 Youtube Series - How Hitler, Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin Spent Christmas

- 12-'20: Photo report Candles on Airborne War Cemetery Airborne Cemetery Oosterbeek

- 12-'20: Christmas far from home, GI’s in Europa during the Holidays of 1944

Latest news

- 12-04: Understanding the German side of the fighting in Normandy

- 03-03: A WWII helmet returns home 80 years after having been lost at Remagen Bridge, Germany

- 16-02: Armin T. Wegner and his letter to Hitler

- 14-02: The hugely popular ‘Standing with Giants’ installation returns to the British Normandy Memorial

- 27-01: Russia focuses on Soviet victims of WW2 as officials not invited to Auschwitz ceremony

- 27-01: Oswald Kaduk, ‘Papa Kaduk’ or a monster??

- 12-'24: Christmas and New Year message from our volunteers

- 11-'24: New book: Righteous Behind Barbed Wire

- 11-'24: Postal artifacts provide a vibrant testament to the experiences of the Dutch people during WWII

- 10-'24: DigitalBattlefieldTours unlocks military tactics to a wide audience