McCarthy, Joseph Charles "Big Joe"

- Date of birth:

- August 31st, 1919 (Long Island/New York, USA)

- Date of death:

- September 6th, 1998 (Virginia Beach/Virginia, USA)

- Service number:

- J/9346

- Nationality:

- American

Biography

Joseph Charles McCarthy, born 31 August 1919 in St James, Long Island, was the eldest son of Cornelius and Eve McCarthy. His father, a clerk, later became a firefighter after working as a bookkeeper in a shipyard. The family moved to the Bronx, but kept a summer home on Long Island, where Joe excelled as a swimmer, baseball player, and lifeguard at beaches like Coney Island.

After his mother’s passing when he was eleven, his grandmother managed the household. In his late teens, he and his friend Don Curtin pursued flying lessons at Roosevelt Field, then the busiest U.S. airfield. When World War II began, Joe repeatedly attempted to join the US Air Corps but was rejected due to his lack of a college degree. Frustrated, he and Don took a bus to Ottawa in May 1941 to enlist with the RCAF, only to be told to return in six weeks.

By late 1941, both had earned their pilot wings and embarked for Liverpool.

Further training led him to 14 Operational Training Unit, where, on 31 July 1942, he participated in a major raid on Düsseldorf involving 630 aircraft. McCarthy’s first mission was uneventful.

In September 1942, McCarthy joined 97 Squadron’s conversion flight to train on Lancasters. After completing conversion training, McCarthy was initially posted to 106 Squadron at Coningsby. However, he was reassigned to 97 Squadron at Woodhall Spa to replace losses.

On 2 October 1942, McCarthy flew his “Second Dickey” trip to Krefeld as co-pilot. Three days later, he completed their first full mission, attacking Aachen amid severe icing that left holes in the cockpit windows.

By 22 March 1943, McCarthy had completed 33 operations, was promoted to Flight Lieutenant, and recommended for a DFC.

The day of the Raid on the Dams:

McCarthy’s crew prepared to take off in Lancaster ED923, "Queenie Chuck Chuck," but a coolant leak forced them to switch to AJ-T, a newly arrived spare. A chaotic scramble followed—McCarthy’s parachute snagged, his compass card was missing, and he barreled into the flight office like a “runaway tank” to retrieve it. Meanwhile, Dave Rodger had ground crew remove a panel in his rear turret.

AJ-T finally took off 33 minutes late, with engineer Bill Radcliffe pushing its speed to regain time, cutting the delay to 16 minutes by the Dutch coast. Unaware that the Second Wave was faltering—Byers shot down, Munro and Rice forced to abort, Barlow crashing—McCarthy pressed on. In enemy territory, they lost radio contact, the GEE navigation system failed, and a light illuminated them as a target. Radcliffe smashed it with a crash axe, and Len Eaton later restored radio communication.

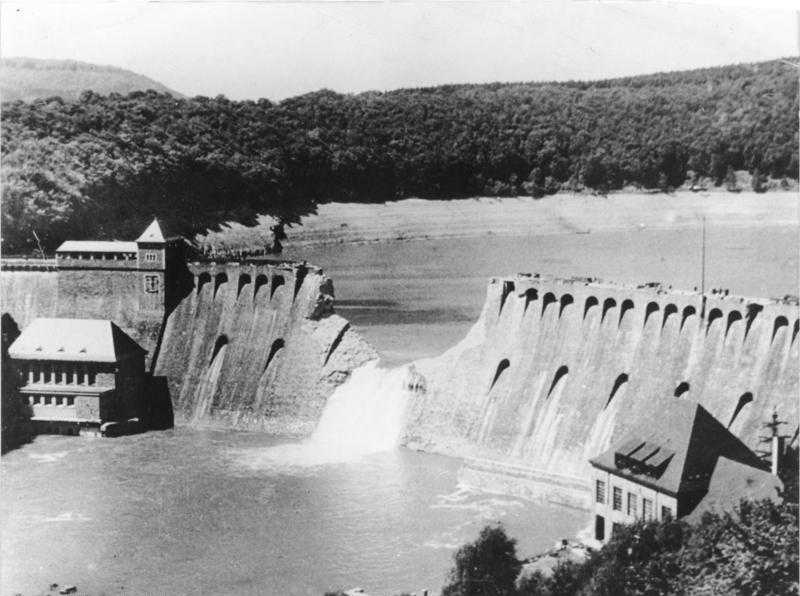

At Sorpe, McCarthy saw they were alone and grasped the challenge ahead, despite the absence of flak defenses. The attack required flying low over Langscheid, using its church steeple as a marker. After nine failed attempts, he executed a near-perfect run at 30 feet, allowing Johnson to release the mine. “Bomb gone,” Johnson shouted, met by a relieved “Thank God” from Dave Rodger, exhausted from the buffeting.

McCarthy then detoured to the Möhne, confirming its breach before heading home. A navigation error led them over heavily defended Hamm, where they dodged enemy fire while manually navigating out of hostile territory. As they approached Scampton, they discovered a shot-through undercarriage tire—but McCarthy still landed safely.

McCarthy attended his DSO presentation ceremony at Buckingham Palace on 21 June 1944.

Remaining with 617 Squadron for 13 more months, he flew 34 additional missions.

After the war, McCarthy returned to Canada, marrying Alice, the American girlfriend he had met in 1941. They had two children, and he became a Canadian citizen to stay in the RCAF. Retiring in 1968, he moved to Virginia, working in real estate. Over his career, he flew nearly 70 aircraft types. He passed away in Virginia Beach on 6 September 1998.

Do you have more information about this person? Inform us!

- Period:

- Second World War (1939-1945)

- Rank:

- Flying Officer

- Unit:

- No. 97 (Straits Settlements) Squadron, Royal Air Force

- Awarded on:

- May 14th, 1943

- Period:

- Second World War (1939-1945)

- Rank:

- Flight Lieutenant

- Unit:

- No. 617 Squadron, Royal Air Force

- Awarded on:

- May 28th, 1943

- Awarded for:

- Operation Chastise

- Period:

- Second World War (1939-1945)

- Rank:

- Acting Squadron Leader

- Unit:

- No. 617 Squadron, Royal Air Force

- Awarded on:

- April 28th, 1944

Awarded as bar on the ribbon of the first medal.

- Period:

- Second World War (1939-1945)