The War at Sea

By Francis E. McMurtrie

The War Illustrated, Volume 8, No. 194, Page 422, November 24, 1944.

Although U-boats are far from being extinct, there being still some hundreds in service, their area of operations has been greatly reduced. There appear to be none left in the Mediterranean, and they have been driven out of the Channel and Bay of Biscay. Their principal ocean bases are now on the coast of Norway. It was from one or other of these Norwegian harbours that the "wolf-pack" issued to make the abortive attack on an Arctic convoy described in the Admiralty communiqué of November 4, 1944. At least three of the enemy submarines were destroyed, and others damaged, some of which may possibly have failed to get back to port. Not a single merchant vessel sustained any damage, our only loss being H.M.S. Kite, a sloop of the war-built "Wren" class.

Operations were conducted by Vice-Admiral F. H. G. Dalrymple-Hamilton, who was captain of H.M.S. Rodney during the action which culminated in the sinking of the Bismarck in May 1941. Complete co-operation between naval aircraft from H.M.S. Vindex and Striker, escort carriers, and a number of escort vessels, which included two destroyers, three sloops and a frigate, proved highly effective in countering enemy efforts to approach the convoy. If the Germans can do no better than this within a limited distance of the bases in which the majority of their U-boats are now concentrated, it does not say much for their chances of renewing the Battle of the Atlantic on terms likely to yield them any advantage.

Fuller reports on the Battle of the Philippines make it plain the Japanese Navy has been dealt a staggering blow. It would seem unlikely that another sea action of importance will be fought until Allied fleets are in a position to advance into Japanese home waters, as the damage inflicted on the ships that regained port may keep them under refit for some time to come.

It is not clear what induced the enemy to give battle in such unfavourable circumstances. Some while back it was announced in a broadcast from Tokyo that the Japanese fleet would fight only when it had the cover of land-based aircraft; and it may have been the plan to use the airfields in Formosa and Luzon for this purpose. Yet both these islands, as well as Mindanao farther to the south, had been very thoroughly bombed by Allied air forces for more than a week before the action, and a large number of Japanese planes destroyed. So far from this giving pause to the enemy, it seems to have precipitated matters, the concentration of his squadrons being arranged in such a way that the U.S. Third and Seventh Fleets obtained every advantage from their central position in the area of operations.

Probably the Japanese were misled by exaggerated reports of damage inflicted on the U.S. fleets by air attack over a week earlier; in fact, only a couple of ships were damaged, neither to an extent sufficient to prevent her proceeding to a repairing base. On the other hand, the toll taken of Japanese land-based aircraft was so heavy that their force proved quite inadequate to provide complete cover for the three squadrons into which the enemy had divided his forces, and were themselves outfought by U.S. carrier-borne aircraft.

Annihilation of Japanese Squadron coming from Direction of Singapore

It may have been hoped that the approach of the largest of these squadrons, coming from the direction of Japan, would divert the attention of the U.S. Third Fleet under Admiral Halsey, and the Seventh Fleet, under Vice-Admiral Kincaid, to an extent that would enable the other two enemy detachments to effect a surprise attack. So far from this being the case, the squadron coming from the south-westward (the direction of Singapore) seems to have been the first to be sighted, with the result that it suffered annihilation. Two battleships (the Huso and Yamasiro, of 29,330 tons), four cruisers and seven destroyers were sunk, either in the course of the action or during their subsequent retreat through waters commanded by Allied aircraft. Earlier, this force had been attacked by U.S. submarines during its passage from Singapore, and had thus lost a couple of cruisers before entering Philippine waters.

Japanese Battleship Yamato, ablaze from stem to stern, with bombs blasting her forward turret, during the furious 3-day engagement in the Philippines toward the end of October 1944. Photo, Associated Press.

Japanese Battleship Yamato, ablaze from stem to stern, with bombs blasting her forward turret, during the furious 3-day engagement in the Philippines toward the end of October 1944. Photo, Associated Press.

Air attacks on the enemy force approaching form the north, which seems to have comprised two battleships, four aircraft carriers, five cruisers and six destroyers, were very successful. All four carriers were sunk, as well as a cruiser and two destroyers, before the Third Fleet aircraft engaged were recalled to proceed to the aid of the carriers of the Seventh Fleet, which were being attacked by the remaining Japanese squadron.

This squadron, approaching from the westward, had made its way right through San Bernardino Strait and out into the Pacific, off Samar, early on October 24. It included the new 45,000-ton battleships Musasi and Yamato, with three capital ships of older date, eight cruisers and over a dozen destroyers. One of the cruisers was torpedoed, and capsized before close contact was made, and other ships received damage. In action with ships of the Seventh Fleet a second cruiser was sunk and the enemy force was so severely handled that it retreated through the San Bernardino Strait as darkness fell. A third cruiser was sunk by gunfire.

Altogether the total Japanese losses in these engagements were summed up by Admiral Nimitz as two battleships, four carriers, nine cruisers and nine destroyers. Severe damage was inflicted on a third battleship, as well as on five cruisers and seven destroyers; some of these ships may have failed to get home. Almost all the other enemy ships also received injuries, though of a less serious character. Ships of the Third and Seventh fleets lost were the light fleet aircraft carrier Princeton, of 10,000 tons; two escort carriers; tow destroyers; one destroyer-escort, of a type rated as frigates in this country; and a few craft of less importance. U.S. submarines and aircraft had an important share in the victory.

It is now know that the casualties in H.M.A.S. Australia, mentioned in page 390, were caused by a Japanese bomber crashing on her bridge after its pilot had been killed.

What strength can the Japanese Navy still muster? It is improbable that there remain in service more than six or possibly seven battleships, seven or eight aircraft carriers, between 20 and 30 cruisers, 70 destroyers and under 100 submarines. This is not a force with which any great enterprise can be attempted. The U.S. Navy alone is capable of putting into the line about three times as many ships in each of these categories.

Previous and next article from The War at Sea

The War at Sea

In the Far East the pace of the war is increasing. The First Lord of the Admiralty has stated that "a fleet capable in itself of fighting a general action with the Japanese Navy" is being transferred

The War at Sea

It is a truism to say that modern warfare depends entirely upon supplies of oil being plentiful. Ships, aircraft, tanks and transport all rely for propulsion upon petroleum in a more or less refined f

Index

Previous article

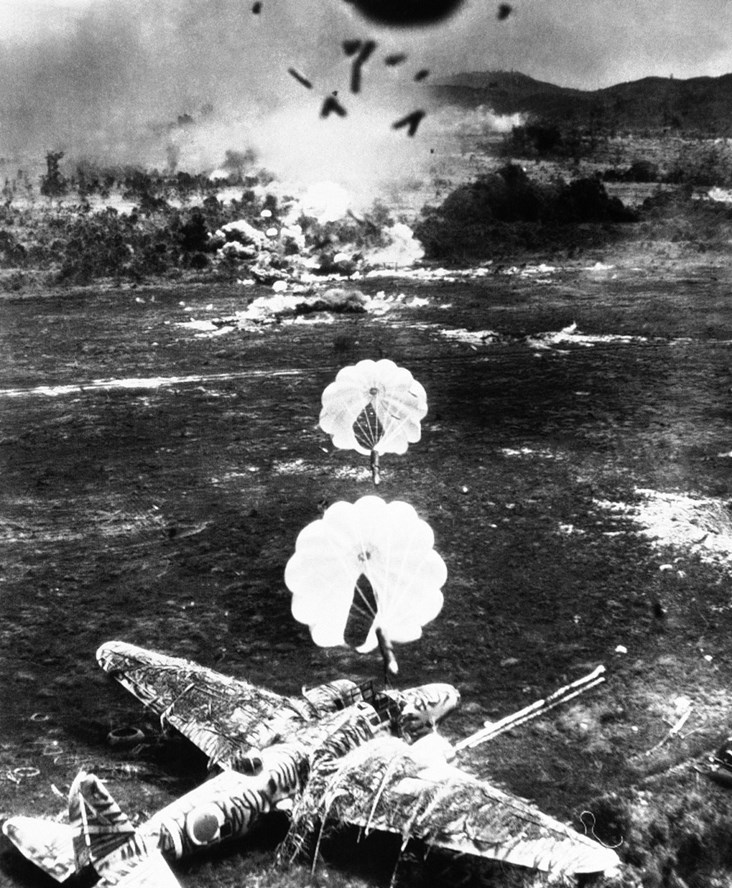

Parachute-Borne Fragmentation Bombs in Action

Terrific Damage was Wrought, on Japanese airfields by U.S. Army Air Forces during a raid on Buru Island, near Celebes, in the battle for New Guinea in July 1944. A few seconds after this photograph

Next article

Dempsey's Men Hurl Enemy Back to the Maas

On a Mopping-up Foray, on Sherman tanks, these smling troops of General Dempsey's British 2nd Army are seen on the thickly-wooded outskirts of Hertogenbosch which had been finally cleared by October