Secret Service Agents Helped to Win the War

The War Illustrated, Volume 9, No. 211, Page 174, July 20, 1945.

The suggestion recently made in the U.S.A. that they should endeavour to build up an Intelligence Service on the British model is a compliment even greater than that paid to us after the 1914-18 war by the Germans, when the latter declared that the superiority of our espionage system undoubtedly had proved disastrous to them. Striking facts are here revealed by PETER LEIGHTON.

A V2 storage depot between two hospitals was one of the targets of Spitfire bomber pilots when they attacked rocket launching sites in Holland yesterday…Several trains loaded with supplies for the front were found and destroyed outside Deutz near Cologne…Shortage of raw materials is believed to be the explanation of the fact that several large plants at the Leuna Works of the I.G. Farben were idle for four days last week…Common enough were these reports during the war in Germany.

How was that storage depot discovered? How was it known that certain vitally loaded trains would pass the station of Deutz at a given time? How did it become known that the Leuna Works were idle? Photographic reconnaissance can, of course, work wonders, but we have yet to get a camera that sees inside buildings and looks up time-tables.

The answer to the question how these typical pieces if vital knowledge were obtained can be given in one word-"Intelligence." That covers many things, involving hundreds, possibly thousands, of men and women who are willing to risk their lives in obtaining information. You can call them spies, if you like, but only a few of the Secret Agents are traitors to their own country, ready to sell information to anyone. The most valuable information comes from men and women to whom fame and monetary reward are secondary. These who take their lives in their hands to ferret out the enemy’s secrets get no medals. For obvious reasons their names and stories seldom appear in the newspapers.

But over 40 names of people appeared in headlines of German papers last year as having been executed for "intelligence with the enemy." No details were given as to what they did or how they were caught. It is possible some of them were not Agents at all. The Gestapo would rather execute ten innocent people than allow one spy to slip though the net. Reading the names, one wonders what stories may eventually be told in full. There was the elderly Flora Tropfer, mother of five children, for instance. She was executed "as a British spy" in Mullhouse under German occupation. And Arno von Wedekind, described as a Swiss student, devoted to the study of philosophy in the University of Gottingen.

Germans Revealed Luftwaffe Secret

The typical spy is not a Carl Lody, a Sydney Reilly or a Mata Hari. In spite of Hollywood films, the success of an Agent must depend upon his being so very ordinary, having regular work and a normal background. There very few super-spies these days. The really big men in Intelligence do not go to enemy territory. Their task is to weld together a score or a thousand separate reports, often the most prosaic and apparently unimportant kind, sent by the Agents who actually do the "spying."

The days when blue-prints of secret weapons or other documents might be stolen in trains (if, indeed, those days ever existed) are over. But occasionally valuable information may be picked up by the sheerest luck. Air Vice-Marshall C.E.H. Medhurst, the intelligence Service expert, early in the war, told how an Englishman making a journey in Italy got inti a compartment with two Germans and an Italian. The Germans swopped stories and then, gently chaffed by the Italian, blurted out why the Luftwaffe kept flying to the Shetlands but never dropped bombs there. The Englishmen, whose name of course may not be revealed, reported the conversation. It meant nothing to him. But to our technical experts it was the clue to a line of radio research that the Nazis were pursuing, of which our authorities had no previous inkling. To say that this information led to the saving of the lives of hundreds of our merchant seamen would be no exaggeration.

One of the most effective pieces of intelligence work was at Peenemunde. Reconnaissance planes may have given us clues to the importance of the place, but where the Nazis thought we obtained our information was obvious immediately after the great raid which set their V-weapon campaign back a year. The place was at once swamped with Gestapo men who put every civilian within miles "through the hoop." What staggered them was our exact information that at a certain time on a certain day a certain building at Peenemunde would be filled with scientists, technicians and high officers of the Luftwaffe; 5,000 of them were reported to have been killed in the raid, including Germany’s "V-weapon genius" General von Chamier-Glisczensky, and the Luftwaffe’s chief of staff General Jeschonnek. There were medals for the R.A.F. who carried out the raid. There were no medals for the spies! Possibly they themselves perished in the raid.

Months before D-Day and up to the end of the war in Europe hundreds of men and women were dropped by parachute on enemy held territory, including two British girls, who played small but vital parts in our preparations for invasion. One revealed that she was twice searched by the Germans, but had always written anything vital on toilet paper, her searchers rapidly passed over in embarrassment. "Carpetbagging" was the code word for these dropping operations. A fortnight before D-Day, Liberators flew by night from bases in Dijon, France, with Agents who parachuted down in Southern Germany and sent by radio to London urgent reports of enemy movements. Crews on this and other expeditions were all sworn to secrecy, the most stringent security arrangements were enforced at the base aerodromes, none but the station commander and crew were allowed contact with the Agents who were to be their passengers; and that meeting was only an hour or two before take-off.

Often Extremely Dull Routine Work

In the year of Munich (1939), Parliament voted the modest sum of £180,000 for our Secret Service. During the war years Parliament has, for obvious reasons, given a blank cheque. But the sum spent is not vast. Many of our agents are patriots who want no more than enough to keep up the pretence that is vital to them. Many are engaged on extremely dull routine work. One may have nothing to do but watch trains go by on a particular stretch of line that can be seen from his window. Maybe he has to pretend to be an invalid and lie up, naturally with the bed drawn near to the window. Nothing happens for weeks, perhaps months. Then one day the rhythm of the traffic is changed. Passenger trains are held up while a heavy goods train is shunted on to a branch line. Next day it is the same…And later the R.A.F. drop 1,000 ton of bombs on a new factory that the Germans thought was completely concealed and unknown to us.

Parachute and portable wireless have revolutionized intelligence work. It is interesting to recall that it was five French parachutists, dropped behind the German lines in 1918, who solved the mystery of the shells falling on Paris and revealed the existence of the Big Bertha Gun. It was the brilliant work of Lieutenant N.L.A. Jewell, R.N., in his submarine that paved the way for the Anglo-American landings in North Africa in November 1942. This episode, and others prior to D-Day on the beaches of Normandy, as well as in Sicily and Italy, resulted in the coining of the phrase "Undersea Secret Service."

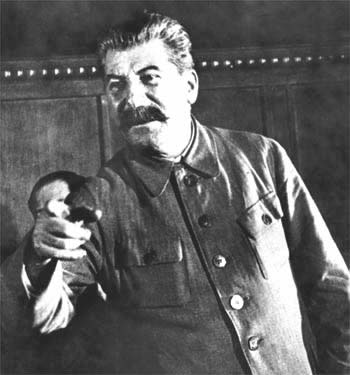

Mr. Churchill in the House of Commons has paid tribute to the work of our Intelligence Agents and told how the many reports, often apparently of no importance, have frequently enabled a picture of what was happening to be pieced together. It was no accident that Mr. Churchill was able to give Marshal Stalin warning of the impending German attack on Russia in June 1941, and to tell him but how many divisions it would be made.

We have no elaborate schools for espionage such as the Germans had at Sonnhofen, and on the outskirts of Hamburg, with its laboratories for the faking of official papers. But the war has proved that our Intelligence is one of the best organized in the world. Hitler’s V-weapons, as further instance, were known to our experts before they appeared over here.

Index

Previous article

Now It Can Be Told! - Phantom Patrols: G.H.Q. Liaison Regiment

Commanded by Lieut.-Col. A. H. McIntosh, this remarkable organization founded by Maj.-Gen. Hopkinson (killed while commanding the 1st Airborne Division in Italy) began secret operations early in 1940,

Next article

Now It Can Be Told! - Our "Met" Men Fought Germans in the Arctic

The arctic wastes of Spitsbergen were in 1942 the scene of a great Allied adventure – it was disclosed on June 9, 1945 – when a small meteorological party, established there to obtain vital weathe