The Daring Raid on Rommel's H.Q.

By Kenneth Hare-Scott.

The War Illustrated, Volume 10, No. 247, Page 515-516, December 6, 1946.

In 1940 and 1941 the plight of the Allies precluded any major offensive in Europe and caused the world to turn its gaze upon the British Empire's struggle in the Middle East. The campaigns in North Africa – initiated by Wavell and concluded gloriously by Alexander and Montgomery – destroyed the Italian Armies and were eventually to expel the Nazis from African soil, smarting under their first major defeat of the war. The fighting lasted many months, and as many heroic deed are recorded in the annals of the soldiers of the Western Desert. None, however, is so worthy a story of British gallantry as the raid by the men of No. 11 Scottish Commando upon the residence and Headquarters of the General Officer Commanding the German Forces in North Africa, Field-Marshal Rommel.

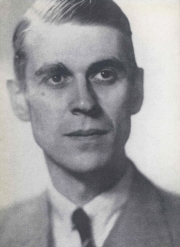

Late in 1941 a large-scale advance by the 8th Army was planned with the object of relieving Tobruk, then besieged for many months, and rolling back the Axis army with such heavy losses in men and material that the security of Egypt and our Mediterranean bases would be assured. At that time Colonel (later Major-General) Robert Laycock was flown out, on the instructions of the Prime Minister, to organize the Commandos; but on his arrival there remained only No. 11 Unit, commanded by Lieut.-Col. Geoffrey Keyes, son of the famous Admiral who was at that time Director of Combined Operations.

Laycock found Keyes engrossed upon a plan for raiding Rommel's Headquarters. He did not share Keyes' enthusiasm, expressing the opinion that "the chances of being evacuated after the operation were very slender, and the attack on General Rommel's house in particular appeared to be desperate in the extreme. This attack, even if initially successful, meant almost certain death for those who took part in it." But Keyes and his Commandos were not to be deterred. The elimination of Rommel might well crumple Axis resistance, and such a project 250 miles in the rear of the enemy, timed to coincide with the 8th Army's attack, was worth a gamble, however desperate the odds.

Exhausting Landings On the Beach

Accordingly, at 4 p.m. on Monday, November 10, 1941, two officers and 25 other ranks, under Keyes' command, embarked upon the submarine Torbay at Alexandria. Three days later – on the Thursday – they arrived off the selected beach and carried out a periscope reconnaissance of the surrounding area. The following day preparations were made for disembarkation, and at dusk the Torbay surfaced. The first seven rubber boats pulled away and after a few upsets soon reached the shore, where Senussi guides led the force to a cave. Owing to the increasing swell and the inexperience of some of the soldiers several of the remaining boats capsized many times.

Eventually, however, all were landed, after an exhausting experience. According to the Torbay's narrative, "Those of the crew who took part received a very severe buffeting while handling the boats alongside in the swell and nearly all of them were completely exhausted at the finish. No less splendid was the spirit of the soldiers under strange and even frightening conditions. They were quite undaunted by the setbacks experienced, and remained quietly determined to get on with the job."

During the landing the men had been soaked through, not only by their immersion in the sea but by heavy rain. A few hundred yards from the beach a cave afforded good shelter, and with the aid of a fire, clothes were soon dried and spirits cheered. By 2 a.m. the landing was completed. Unfortunately the second submarine with Col. Laycock's party had not been so successful in making the beach, and only a handful of men were landed to reinforce those form the first submarine. During the evening the men rested, dried their clothes and fed themselves while Keyes continued to supervise the landing of stores and equipment.

The morning of the 15th brought sunshine and an anxious moment. An enemy ambulance aircraft flew overhead at 800 feet, but failed to detect the party. As little more than half the original force had been able to land the plan for the attack needed modification and, in consultation with Laycock, Keyes spent the morning doing this. In the afternoon the new plan was explained to the men, and the evening was spent in opening, repacking, and distributing ammunition, explosives, and rations. A local Arab shepherd had been enrolled as a guide to substitute for two Senussi from the Arab Battalion who had failed to land.

Inland March Over Rocky Tracks

During the latter part of the afternoon more rain had fallen and it was a damp and cheerless company of men who set off at 8 p.m. on their march into the interior. The difficulty of the conditions and the spirit of determination which prevailed are best disclosed in this personal record of Captain Robin Campbell who was at Keyes' elbow throughout the operation:

"That night we reached the top of the first escarpment (which is half a mile inland) at about 9.15 p.m., I imagine, after a fairly stiff climb, and all that night we marched inland over extremely difficult going, mostly rock-strewn sheep tracks. Our guide left us at about midnight, fearing to go any farther in our company. Geoffrey then had the difficult task of finding the way by the aid of an indifferent Italian map, his compass and an occasional sight of the starts. Just before light he led us to the top of a small hill, arranged for relays of sentries, and ordered the rest of the party to disperse among the scrub for sleep."

Drizzle and a scare ushered in the next morning. The sound of excited shouting brought a report from a Palestinian soldier, who was a member of the party, t the effect that the force was surrounded by armed Arabs. Rascally-looking Arabs brandishing short Italian rifles seemed everywhere, but they appeared neither particularly formidable nor implacably hostile, so Keyes gave the order for the chief to be brought to him for a talk. A few civilities were exchanged and, although a letter from the Chief of all the Senussi Tribes, instructing his subjects to co-operate, was unintelligible to a "Deputy Chief" who could not read, a promise was eventually made that at nightfall he would guide the force to a cave within a few hours' march of their objective. Meanwhile, a kid would be prepared for them to eat. Later an Arab boy, on instructions from his chief, produced cigarettes for Keyes' men; he had run off and bought these from an Italian canteen while the meal was in progress!

When darkness fell the march continued, and two and a half hours later the cave which the Arab had mentioned was reached. It was roomy, dry, and – apart from an appalling smell of goats – an ideal place to spend the rest of the night. At daybreak the party moved to a small wood, and here Keyes left Campbell in charge while he went off on a final reconnaissance with the Arab guide, Sergeant Terry, and Lieutenant Cook, who was to lead the party attacking a communications pylon near Rommel's Headquarters. The result is again best described in Campbell's own words:

"Geoffrey told me that he had been able to see in the distance the escarpment, about a mile from the summit of which lay Rommel's Headquarters and that he was going to try to prevail upon the Arab to send his boy to the village of Sidi Rafa (the Italian name for which is Beda Littoria) to spy out the lie of the Headquarters building and report on the number of troops he saw there, and so on, before making his final, detailed dispositions for the attack. The boy set off after receiving careful instructions from Geoffrey, who had promised him a big reward if he brought back the desired information. This proved a brilliant move, for when the boy returned a good many hours later Geoffrey was able to draw an excellent sketch map of the house and its surroundings, enabling him to make a detailed plan of attack and to give the men a good visual notion of our objective."

A thunderstorm and heavy rain which followed turned the countryside to mud before the eyes of the party; and spirits sank at the prospect of a long, cold, wet and muddy march before reaching the starting point of a hazardous operation. The men passed the time eating, dozing, or collecting water from the dripping roof in empty bully-beef tins.

From the start the attack had been planned for midnight, November 17-18, 1941, to coincide with the launching of the big offensive in the Western Desert. In view of the state of the ground, Keyes, decided to allow six hours to reach his objective. At 6 p.m. the company assembled with parade ground precision for the final stage of the operation, and at a whistle signal the march began. Rain continued and, ankle deep in mud, the men slipped and staggered through the night. Occasionally one would fall and the column would halt for his recovery. Another would lose touch with the man in front of him, and a reshuffle would mean further delay.

Grim Encounter at Close Quarters

At 10.30 p.m. the bottom of the escarpment was reached, and after a short rest the 250-foot climb of muddy turf with occasional protruding rocks was begun. A man slipped, and in striking his tommy-gun against a rock roused a watchdog. A stream of light came from the door of a hut as it was flung open, 100 yards away. The party crouched motionless. The dog received a rebuke, and presently the door closed and the march was resumed. At the summit Cook and his party detached themselves, and those who remained, about 30, continued along a path towards Rommel's Headquarters. At this point the guides could stand the strain no longer and fell back, having been promised that their reward would be forthcoming when they linked up with the returning body at the conclusion of the operation.

At 11.30 p.m. the outbuildings were reached, and Keyes with Sergeant Terry made the final reconnaissance of the building. Again a dog proved troublesome. His furious barking brought an Italian and an Arab from a hut, and it required Campbell's best German and his Palestinian interpreter's Italian to convince them that a "German" patrol did not like being interrogated! When Keyes returned he led his men into the garden of the house and here again Campbell's own account can be taken up.

"We followed him around the building on to a grave sweep before a flight of steps at the top of which were glass-topped doors. Geoffrey ran up the steps. He was carrying a tommy-gun for which he needed both hands and, as far as I remember, I opened the door for him. Just inside we were confronted by a German in steel helmet and overcoat. Geoffrey at once closed with him, covering him with his tommy-gun. The man seized the muzzle of Geoffrey's gun and tried to wrest it from his grasp. Before I or Terry could get round behind him he retreated, still holding on to Geoffrey, to a position with his back to the wall and his either side protected by the first and second pair of doors at the entrance. Geoffrey could not draw a knife and neither I nor Terry could get round Geoffrey as the doors were in the way, so I shot the man with my .38 revolver, which I knew would make less noise than Geoffrey's tommy-gun. Geoffrey then gave the order to use tommy-guns and grenades since we had to presume that my revolver shots had been heard.

"We found ourselves, when we had time to look round, in a large hall with a stone floor and stone stairway leading tot he upper storeys and with a number of doors opening out of the hall. We heard a man in heavy boots clattering down the stairs, though we could not see him, or he us, as he was hidden by a right-angle turn in the stairway. As he came to the turn and his feet came in sight, Sergeant Terry fired a burst with his tommy-gun. The man fled away upstairs. Meanwhile, Geoffrey had opened one door and we looked in and saw it was empty. Geoffrey pointed to a light shining from the crack under the next door, and then flung it open. It opened towards him, and inside were about 10 Germans in steel helmets, some sitting and some standing. Geoffrey emptied his Colt .45 automatic, and I said, "Wait, I'll throw a grenade in." He slammed the door shut and held it while I got the pin out of a grenade. I said, "Right!" and Geoffrey opened the door and I threw in the grenade which I saw roll in the middle of the floor.

Died As He Was Carried Outside

"Before Geoffrey could shut the door the Germans fired. A bullet struck Geoffrey just over the heart and he fell unconscious at the feet of myself and Sergeant Terry. I shut the door and immediately afterwards the grenade burst with a shattering explosion. This was followed by complete silence, and we could see that the light in the room had gone out. I decided Geoffrey had to be moved in case there was further fighting in the building, so between us Sergeant Terry and I carried him outside and laid him on the grass verge by the side of the steps leading up to the front door. He must have died as we were carrying him outside, for when I felt his heart it had ceased to beat."

The men's spirits fell when they heard of their Colonel's death – his inspiring leadership gone. Almost immediately afterwards Campbell was shot through the leg, and subsequently taken prisoner. Terry mustered the remainder of the party and began the long march back to join Laycock on the beach.

Rommel, by chance, was away from his Headquarters that night and so eluded the fate designed for him by the courageous Commandos. At Keyes' funeral, at Sidi Rafa, Rommel made an oration and pinned his own Iron Cross on the body of the dead hero. This token of admiration for the bravery of his personal antagonist by an enemy Commander-in-Chief must be unique in the history of chivalry.

When the official account of the raid could be made known Geoffrey Keyes was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross, on June 19, 1942. A Memorial Service held in Westminster Abbey was attended by many Commandos who had shared with him the events of that week in November 1941.

Previous and next article from Great Stories of the War Retold

Cassino: Ypres of the Second Great War

By L. Marsland Gander, who as War Correspondent of The Daily Telegraph saw the capture of Monastery Hill and the town of Cassino in May 1944. The jagged, piled masonry of Cassino today poses one of

The First Attack by British Parachutists

On February 10, 1941, a small band of determined men dropped by parachute from six R.A.F. aircraft through a starlit sky in Souther Italy. Their mission was to demolish an important aqueduct not far f

Index

Previous article

His Majesty's Ships - H.M.S. Illustrious

First fleet aircraft carrier to be completed after the outbreak of war, H.M.S. Illustrious, of 23,000 tons, was launched at Barrow in 1939. Her outstanding achievement, as flagship of Rear Admiral (no

Next article

His Majesty's Ships - H.M.S. Javelin

Motto: “Vi et Armis.” A destroyer of 1,760 tons, H.M.S. Javelin was completed shortly before the outbreak of war in 1939. In the early hours of November 29, 1940, she was the leader of a small