Prologue

Field marshal Bernard Montgomery is not undisputed. On the one hand, he was the one who defeated the German Afrika Korps in late 1942 adding a little luster again to the blemished British blazon; he was also very much concerned about the fate of his soldiers. On the other hand he was known as egocentric, tactless and insinuating, especially to the Americans. He also was the mental father of Operation Market Garden which ended in disaster. Walter Bedell Smith, Chief of Staff of Dwight Eisenhower during the war, said to him: "You may be great to serve under but you sure are hell to serve over."

Definitielijst

- marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

Images

Childhood and First World War

Bernard Law Montgomery was born November 17th, 1887 in Kensington, a district in Central London. He was fourth out of a total of nine children of whom seven survived. His father, Henry Montgomery was the Anglican priest in St. Mark’s Church in Kensington. Montgomery’s mother Maud Farrar was 18 years younger than her husband. When Bernard was two years old, his father was appointed Bishop of Tasmania, at the time still a British colony. The family moved to the island south of Australia were Bernard spent the remainder of his childhood. Life in the far away colony was, in his own words, very harsh and lonely for young Montgomery, not in the least because of the cruel behavior of his mother.

In 1901, the family moved back to London because Henry Montgomery was offered a job there. He became secretary of the United Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. In London, Montgomery attended St. Paul’s school, a private boys school. He was an average student and neglected his education but he liked playing sports such as rugby and cricket. In sports, he demonstrated his qualities as a leader for the first time. Montgomery himself declared, by the way, he had had a bad childhood. It was caused, he said, by the strenuous relationship between him and his stern and dominant mother. He also said he had been beaten regularly by her which was caused by his less than flexible nature.

At the age of 19, after having graduated from St. Paul’s, Montgomery enrolled in the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. He was quickly promoted to Corporal but following an incident with a cadet, his stripes were taken from him. In fact, during an admission ceremony, Montgomery had set fire to a student’s clothing who had been tied up. His father managed to prevent him from being expelled from Sandhurst by his mediation. As early as that, Montgomery was described as an eccentric person who seldom bothered about the opinion of others. Yet Montgomery graduated successfully. In 1908 he joined the 1st Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment as 2nd Lieutenant and was stationed in Peshawar in India. He was promoted to Lieutenant in 1910 and in 1912, he was made adjutant of 1st Battalion of his regiment at Shorncliffe Army Camp in Kent.

Shortly after his return to England in 1912, the First World War offered him the opportunity to display his military talents; in August 1914, the regiment was transferred to France. When he was commanding a platoon near Mèteren in France on October 13th, 1914, he was seriously injured by a sniper’s bullet which penetrated his right lung. He owed his life to a soldier who managed to bandage his wounds correctly under enemy fire. This soldier however paid with his life for this rescue action as he was shot in the head by the same sniper. As a result of this wound, Montgomery would suffer from shortness of breath for the rest of his life. Partly because of this, he would hate tobacco smoke.

After having been discharged from hospital, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for extraordinary courage and conspicuous leadership. Early 1916, after a spell in Lancashire as Brigade Major of the 112th and afterwards of the 104th Brigade, Montgomery returned to the front. He was given a staff position and served a while as officer on the general staff of the 33rd Division. In July 1917, he became officer on the general staff of IX Corps, part of 2nd Army under General Herbert Plumer. In this capacity he took part in the battle of Passchendaele in August 1917. Montgomery ended the war as Chief of Staff of the 47th Division, holding the temporary rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- sniper

- Military sniper who can eliminate individual targets at long distances (up to about 800 meters).

Images

Interbellum

The great losses that had been suffered in the First World War made Montgomery realize that the existing tactics were not suitable to achieve a decisive victory. He also found it unheard of that senior officers showed no interest in the fate of the common soldier. He argued he would do things completely different. Yet in his later career, he would make no radical changes to the existing ideas and tactics.

After the First World War, Montgomery was in command of 17th Battalion Royal Fusiliers in the British army at the Rhine. An infantryman in heart and soul, he immersed himself deeply in infantry tactics and training. In 1920, he attended the staff course at the Staff College in Camberley, Surrey. On completion of the course, he was posted to the 17th Infantry Brigade in January 1921 with the rank of Brigade Major. The brigade was stationed in County Cork, Ireland and was engaged in the battle against the IRA, the armed branch of the Irish independence movement Sinn Fein. In the early 20s a war raged in Ireland between the British army and Irish separatists. This war ultimately led to the independence of Ireland.

After these experiences, Montgomery began drawing attention to himself. In the early 20s when he was active in the 49th Division in York after his return from Ireland, he delivered lectures and fanatically trained his troops. A number of officers here charged him with dictatorial behavior. He was also praised however for his presence among the lower ranks and his simple explanations. Furthermore, he wrote an infantry manual that was severely criticized in certain circles, including the War Office, for his conservative ideas about tactics. In 1925, he returned to the 1st Royal Warwickshire Regiment as company commander and in June of that year, he was promoted to Major.

In 1926, Montgomery was made Deputy Assistant Adjutant General at the Staff College in Camberley holding the temporary rank of Lieutenant Colonel and in 1937, he met his future wife Elizabeth Carter (half-sister of General Percy Hobart). They got married on July 27th, 1927 and August 18th, 1928 their son David was born. In January 1929 he returned once again to the 1st Royal Warwickshire Regiment as Commander of Headquarters Company and during the summer of that year, he worked at the War Office as one of the co-authors of the Infantry Training Manual. Following that, he left for the Middle East. In 1931 he was given his definite promotion to Lieutenant Colonel and he was appointed commander of 1st Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. He served in the British mandate of Palestine and in the British colony of India. June 1934 saw him promoted to Colonel. He was posted to the Indian Army Staff College as instructor in Quetta in what is now Pakistan. In June 1937, he and his family returned to England and he was appointed commander of the 9th Infantry Brigade, holding the temporary rank of Brigadier.

In the fall of 1937, on vacation in Burnham-on-Sea, his wife was bitten by an insect while sun bathing and she contracted blood poisoning. In very quick succession, this led to the loss of a leg and her death. Montgomery was deeply shocked by her death and committed himself to his work with full dedication.

In 1938, he organized a combined amphibious exercise, highly impressing senior officers. In October 1938, he was promoted to Major general. He was sent to Palestine to take command of the 8th Infantry Division. In that period, there already was a lot of unrest brewing between Jews and Arabs in the British mandate of Palestine. A state of emergency was declared and Monty was ordered to restore order, managing to suppress an Arabian revolt but in May 1939, he contracted a serious pulmonary disease and was forced to return to Great Britain.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

Images

The beginning of World War Two

After his recuperation he was put in command of the 3rd (Iron) Infantry Division in July 1939. He subjected the soldiers under his command to a rigorous training program. The unit was part of the British Expeditionary Force or BEF, commanded by John Vereker, better known as Lord Gort, that was dispatched to France in September 1939 after Britain had declared war on Germany. The 3rd Infantry Division was part of II Corps, commanded by General Alan Brooke. Montgomery went to France with bravado. He commanded "The best unit of the British Army" and was going to win the war. Soon after the invasion, however, it became apparent that the German troops, partly due to their Blitzkrieg tactics, were superior to the British and French. Following the surrender of the French armies in May 1940, the British were driven back to Dunkirk. The manner in which Monty commanded his division was praised by other officers as a fine example of a rear guard action in most trying circumstances. The situation was made even worse when Montgomery was put in command of II Corps in the last days before the evacuation. General Brooke was forced to pass command to him as he himself had been ordered back to Great Britain in order to take up a higher command. Montgomery managed to lead the troops under his command safely back to England with little loss. On his return he heavily criticized the leadership of the BEF for their conduct during the European campaign, which the War Office did not take lightly.

In July 1940, Montgomery was promoted nonetheless to the temporary rank of Lieutenant General and was put in command of V Corps which was responsible for the defense of Hampshire and Dorset against the expected German invasion. When British Prime Minister Winston Churchill met Montgomery in July 1940, he was impressed by his directness, as he dared to go directly to the Prime Minister with a request for additional means of transport. Subsequently, in April 1941 he was appointed commander of XII Corps, responsible for the defense of Kent. Here he subjected his troops to a rigorous training program and adopted a strong line. He immediately expelled men from the army he considered not fit enough. This seemed better to him than to have these men die in combat. When Churchill learned that Montgomery was forcing his staff officers to run seven miles on a regular basis, he expressed his disapproval. He asked his minister of war: "Does he also run that seven miles himself? If so, then he is probably more useful on a football field than in the war." According to him, a high-ranking officer did not need to have athletic qualities. Only in the Italian army (where many combat actions resulted in a hasty retreat) did a general, according to the prime minister, do well to be able to run fast. In December 1941 he was appointed commander of South-Eastern Command, responsible for the defense of Kent, Sussex and Surrey. In this capacity, he organized a large military exercise in May 1942, involving more than 100.000 men, making a strong impression on other officers.

Montgomery lived amidst his troops which caused the common soldier to like him very much. He did however adopt a less than amicable attitude towards his fellow officers and always took the assumption he was right, even when it was evident he was not. A few times, Montgomery was involved in planning of operations, including Operation Jubilee, the notorious raid on Dieppe in August 1942 when an attack on this French port was repulsed by the Germans. Montgomery played no active role in this operation by the way.

Definitielijst

- Blitzkrieg

- The meaning of this word is “Lightning War”. Short and fast campaign. As opposed to a trench war the Blitzkrieg is very quick and agile. Air force and ground forces work closely together. First used against the Germans (September 1939 in Poland.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

Images

North-Africa

On August 13th, 1942, Montgomery was suddenly and unexpectedly appointed commander of the British 8th Army in North-Africa, succeeding General Claude Auchinleck who was also Commander-in-Chief Middle East Command. Auchinleck was replaced in both functions as he was held accountable for the fall of the Libyan port of Tobruk on June 21st, 1942. In reality he could have done little about this. The fall of Tobruk had been owed more to the fact that Auchinleck did not have capable and determined officers at this disposal. British military historian Antony Beevor writes about this general: "The achievement of Auchinleck cannot be underestimated. In any case he had saved the extremely battered 8th Army from disaster and had stabilized the front line, inflicting heavy losses on the Germans in the process." Churchill only saw missed opportunities, refusing to accept that the troops were exhausted and he subsequently replaced Auchinleck by Montgomery. General Sir Harold Alexander was appointed Commander-in-Chief Middle East Command. Previously, Churchill had earmarked William Gott as commander of 8th Army but he was killed when the aircraft, on its way back from the front to Caïro, was shot down by German fighters on August 7th, 1942. In a letter to his wife, Churchill wrote: "In Montgomery we have an extremely competent, courageous and energetic soldier. If he is a little unpleasant to his supporters at times, he will certainly be so to the enemy."

Previously, 8th Army had been pushed all the way back to Egypt by the German Afrika Korps and had stabilized the front in the first battle for El Alamein. On arrival in North-Africa, Montgomery managed to regain the confidence of the severely battered British soldiers and restore their morale by regularly visiting his troops and subjecting them to rigorous training. He deliberately set fire to the plans for a withdrawal and took no account of previous plans. Only one plan prevailed, his own. Montgomery waited until he had received the promised re-inforcements before attacking. In fact he pursued the same policy Auchinleck had been fired for previously. In contrast to his own words, Montgomery also adopted many of the plans drafted by Auchinleck.

In September 1942, the commander of the German Afrika Korps, Erwin Rommel was forced to begin his retreat. His fuel supplies had been exhausted and his forces were continuously subjected to attacks by the Desert Air Force. The first engagement between Montgomery and Rommel was the short but fierce battle of Alem-Halfa, south of El Alamein (August 30th - September 5th 1942) where a German attack was repulsed. After the arrival of a large amount of re-inforcements, including 300 American M4 Sherman tanks, Montgomery (definitively promoted to Lieutenant general a short while before), went on the offensive. The original plan, which included a large diversionary movement, was not effective. Despite suffering from lack of fuel and ammunition, the German and Italian troops put up a fierce resistance. A renewed attack on November 2nd, 1942 was more successful and the German-Italian forces were routed from the battlefield. This was the highlight of his career and it caused British supreme command to continue supporting him unconditionally.

Later, the victory of the so called second battle of El Alamein, lasting 12 days, would be approached a little differently. Montgomery was familiar with Rommel’s plans as the German codes had been deciphered by the British secret service. Montgomery could have defeated the enemy earlier and more decisively; according to some later historians he had been too slow and too cautious and had won only because his armies were far better equipped than those of the Axis and not because of his capabilities. This criticism was also shared by Winston Churchill. According to British historian Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart, the British victory had been massively exaggerated and inflated. The reason was, the British people yearned for success after the defeats of the previous years. By Montgomery’s caution in attacking the retreating Afrika Korps, he had missed the opportunity to deal a fatal blow to these troops. Montgomery knew the movements of the enemy units exactly through the decoded messages. However, he did not exploit this knowledge sufficiently. Ralph Bennett, a codebreaker at Bletchley Park, called the half-hearted pursuit of the Germans by the British unforgivable. It was, he said, "A completely incomprehensible decision, as an overwhelming amount of Ultra information showed that Rommel's retreating forces could never have repulsed a significant attack.". Moreover, after this battle in November, Montgomery was promoted to General.

Following the Allied landings in Morocco and Algeria (Operation Torch) on November 8th, 1942, the Axis forces were forced to pull back to Tunisia. At his own request, Montgomery was not involved in the preparation for this operation as he did not trust the Americans. In his turn, Montgomery was blamed for not having taken up the pursuit of the Afrika Korps after the second battle of El Alamein. He argued that the British army was not yet ready to defeat the Afrika Korps in a battle of maneuver. He feared a German counter attack and refused to risk his reputation of victor. Beevor and other historians also argue he could not handle tanks properly and that these were not deployed in the right way. This slowed the advance of 8th Army.

Rommel established a defensive line at Mersa Brega, a town in Libya. In December, he abandoned the position. Montgomery pushed on but did not exploit a number of opportunities to encircle the Afrika Korps. On January 23rd, 8th Army marched into Tripoli. Rommel retreated again, this time to the Mareth line in southern Tunisia on the Libyan border. Hitler accused the Generalfeldmarschall of cowardice for giving up so much territory. In retrospect, it can only be said that his retreat was the best executed maneuver of the whole desert campaign. Rommel also managed to inflict a savage defeat on the Americans at Casserine Pass in the Central-Tunisian Atlas mountains in February 1943, costing II Corps, commanded by Major general Lloyd Fredendall over 180 tanks and 6.000 men. As a result of this defeat, Fredendall was replaced by George Patton in March 1943.

Montgomery enjoyed more success than the Americans. On March 6th , he managed to lure part of Rommel’s forces into a trap during the battle of Medenine in southeastern Tunisia and Rommel lost 55 tanks. On April 7th, 1943, units of the American 1st and the British 8th Army made contact. On May 7th, the united American and British troops launched a co-coordinated attack on the remnants of the German Afrika Korps. On May 12th, the Germans and Italians surrendered in Tunisia. 250.000 enemies were taken prisoner-of-war.

Definitielijst

- El Alamein

- City in North Egypt. The Battle of El Alamein took place from October to November 1942 and was a turning point in the war. The German-Italian advance in North Africa was finally halted by the Allies.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Tobruk

- Small bunker. Usually manned by one soldier with a machinegun, but there were also bigger tobruks equipped with a canon or mortar.

- Ultra

- British intelligence service during World War 2

Images

Montgomery watches his tanks advance in North-Africa from a Grant-tank, November 1942. Source: Imperial War Museum.

Montgomery watches his tanks advance in North-Africa from a Grant-tank, November 1942. Source: Imperial War Museum. Montgomery (on the left) accompanies Prime Minister Churchill during his visit to the Libyan desert, August 23rd , 1942. The person on the right is General Sir Harold Alexander. Source: Imperial War Museum.

Montgomery (on the left) accompanies Prime Minister Churchill during his visit to the Libyan desert, August 23rd , 1942. The person on the right is General Sir Harold Alexander. Source: Imperial War Museum.Sicily and the Italian mainland

After having defeated the Axis powers in North-Africa, the British and Americans prepared an attack on Sicily. They hoped that by attacking Italy, typified by Churchill as the weak underbelly of Europe, they could push the country out of the war and weaken the Third Reich. Montgomery did not agree with the initial plans for Operation Husky, the code name for the invasion of the island. He wanted to land his 8th Army in the southeast and wanted Patton to defend his flank. Patton did not agree with this idea, causing tension among the Allied commanders. Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder, commander of the R.A.F. in the Mediterranean, was not at all pleased with Montgomery either. He characterized him during the discussion about Sicily as follows: " A little man of average talents who has come so far he thinks he is Napoleon, which he is not."

Despite these tensions, Operation Husky was launched in the night of July 9th to 10th , 1943. The argument between Montgomery and Patton had not been solved yet. In just one day, over 80.000 men were put ashore from 2.600 vessels. The Germans were totally surprised by the attack, among other things as a result of Operation Mincemeat (an Allied ruse, using the body of a non-existent British officer to get falsified documents into the hands of the German intelligence services). Montgomery’s 8th Army was allocated the southeast angle of the Sicilian triangle. From there, his troops were to move up northwards along the coast to Messina in order to cut off the Axis divisions before they could escape to mainland Italy. Patton’s American 7th Army landed further west on three points on the southern coast. 7th Army had not been given specific targets once it came ashore. Montgomery captured Syracuse on July 1st without too many problems. As his troops advanced further north towards Catania, the German resistance stiffened. Heavy fighting raged around places like Gerbini and the River Simeto where the British suffered heavy losses.

Patton exploited the vagueness of the targets allocated to him by advancing northwards along the coast and subsequently north across the mountains to Palermo. As the Americans were far more motorized than the British, they could advance fast. Patton wanted to capture Messina at all costs ahead of Montgomery. The latter was still stuck south of Catania and agreed to Patton capturing Messina, which in fact occurred on August 17th . The Allies however did nothing at all to prevent the Germans and Italians from pulling back their troops to the mainland in masses. In the end, some 110.000 German and Italian troops were transferred from Sicily to the mainland without hardly any losses. During the Sicilian campaign, 7th Army had lost some 8.800 men (killed, wounded, missing or taken prisoner), Montgomery’s 8th Army some 11.800.

On completion of Operation Husky, the Allies launched an invasion of mainland Italy. The Allies crossed the Strait of Messina on September 9th and British and Canadian troops landed near Reggio di Calabria. On September 9th, units of the American 5th Army , commanded by General Mark Clark, came ashore near Salerno, south of Naples. Montgomery’s 8th Army pushed northwards along the coast of the Adriatic Sea, impeded by the fact that the retreating Germans had blown all bridges on their way north. On September 25th, the American 5th and the British 8th Army made contact. 8th Army captured the Foggia plateau; the airfields there were very useful for the bombing of targets in southern Germany and Austria.

The objectives of the Italian campaign were not clear in advance. Harold Alexander, commander of the 15th Army Group, failed to coordinate the operations of his armies properly which caused tensions. Montgomery often took action only when everything had been meticulously thought over. The official record on the Italian campaign about Montgomery reads: "He had the unusual gift to combine very strong language with very cautious action in a convincing way". He wrote angrily: "Up to now, I had no knowledge of a plan for the development of the battle in Italy but I got used to it in the meantime." Montgomery and Clark did not get along well during the Italian campaign. Clark blamed Montgomery for advancing too slowly with his 8th Army, which had caused problems for him (Clark) at Salerno. Strangely enough though, Montgomery thought he had saved 5th Army near Salerno after it had encountered problems due to continuous German shelling. Moreover, both men were obsessed with their image. Clark had a PR team of no less than 50 men working for him while Montgomery had adopted the strange habit of handing out signed pictures of himself.

The advance of 5th Army ground to a halt in November 1943 in front of the heavily fortified Gustav line between Rome and Naples. Montgomery was up against problems of supply and fierce German resistance. The mountainous terrain in southern Italy was ideal for defense by the Germans. Moreover, the battle here was far more ruthless than in North-Africa. Fierce battles were fought over places such as Ortona. On December 21st, Montgomery suspended all operations. Casualties were running too high and the air force was hardly able to operate because of the bad weather.

Definitielijst

- Gustav line

- German defensive line in the south of Italy to prevent the advance of the Allies.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- shelling

- Indication for shooting targets with grenades. Both from artillery and armoured artillery.

Images

Montgomery and Patton saying goodbye on Palermo airfield on Sicily, July 28th , 1943. The two generaals quarelled over the execution of Operation Husky. Source: Imperial War Museum.

Montgomery and Patton saying goodbye on Palermo airfield on Sicily, July 28th , 1943. The two generaals quarelled over the execution of Operation Husky. Source: Imperial War Museum.Operation Overlord

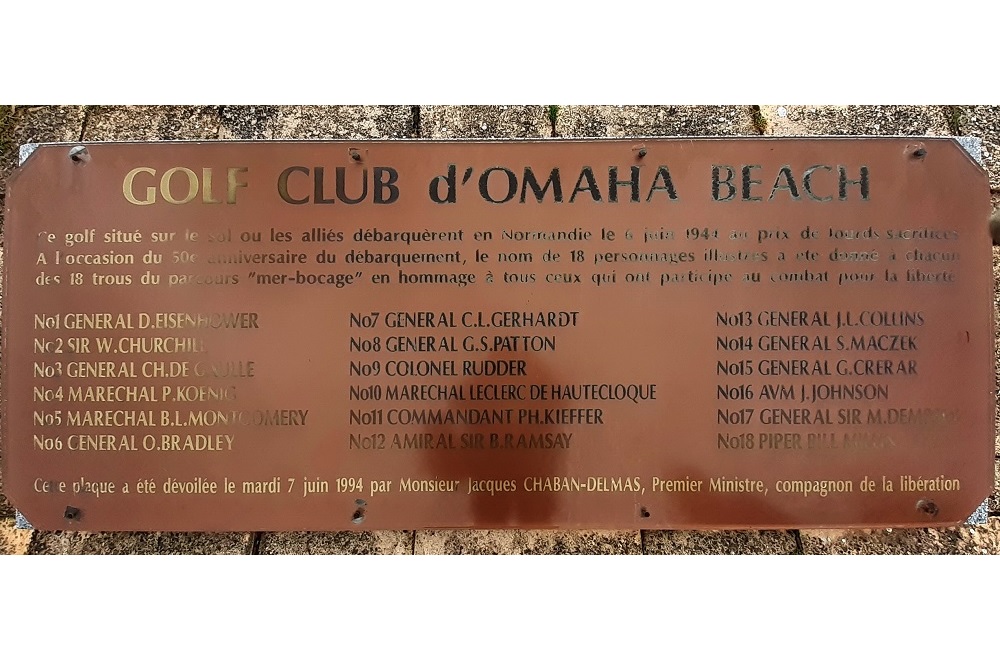

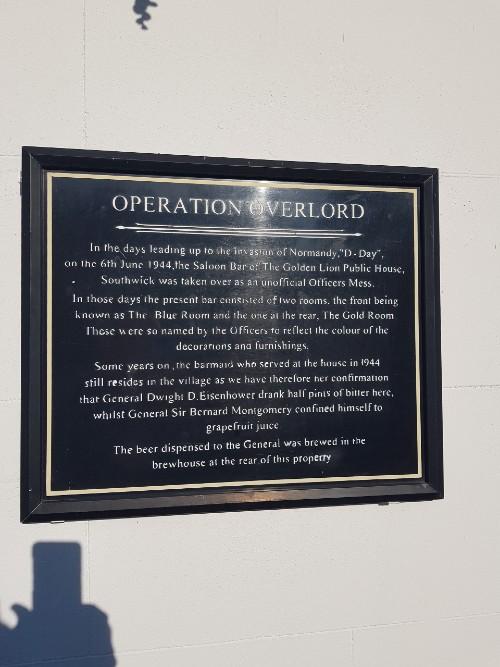

In late December 1943, Montgomery was recalled to Great Britain for the planning and preparation of Operation Overlord, the Allied landings in Normandy. At the request of Eisenhower and Montgomery, the troop strength from the initial draft was enlarged from three to five divisions and the capture of the Cotentin peninsula was also included. Being the representative of Eisenhower, Montgomery was put in command of the 21st Army group, the British and American troops in the early phases of the operation in Normandy. This greatly angered Lieutenants general George Patton and Omar Bradley who could not comprehend that an Englishman was put in command of American troops. The first meeting between Montgomery and Eisenhower did not go smoothly. The Briton reprimanded the chain-smoking Eisenhower when he lit a cigarette in front of him. The relationship between the two would always remain strained. Montgomery also caused much vexation by hardly ever showing up at meetings with the other Allied generals. He thought those discussions could be handled better by chiefs of staff.

After the landings on June 6th, 1944, Montgomery continued to cause friction. His plan was to capture Caen and the area beyond with the British and Canadians troops, who had landed on Juno and Sword Beach, in order to make use of the airfields situated there as soon as possible. This capture was initially scheduled for D-Day itself, June 6th, but the German defense with machinegun nests and anti-tank guns, hidden in Normandy farms and villages proved harder to overcome than anticipated. The Allied intelligence had also failed to notice that the 21. Panzer-Division was already present in the vicinity of Caen. By his continuous ground offensives, Montgomery made Caen into some sort of a symbol. He very hesitatingly acknowledged that there were problems. He kept insisting to Eisenhower that everything proceeded as planned and he skipped issues that did not. He did this to prevent Eisenhower from meddling too much with him. Montgomery accepted neither criticism nor sound advice.

In an attempt to break the deadlock around Caen, Air Chief Marshall Trafford Leigh-Mallory proposed to launch an attack with medium and heavy bombers. Montgomery approved and in the evening of July 7th, 1944, 467 Avro Lancasters and Handley Page Halifaxes launched a devastating attack on the city. During the bombardment, hardly a German lost his life while the French civilian population suffered heavily. The piles of debris, caused by the bombing also presented an obstacle to the advancing troops. The German defenders also were up against problems of supply though, caused by the destroyed infrastructure. The bombardment was a moral boost to the Allied troops as well.

After Rommel had deployed his Panzergruppe West against the British and Canadian sectors, it still took an entire month after D-Day before Montgomery’s forces were able to capture Caen, their first objective, in Operation Charnwood. Various earlier attempts failed dismally, despite Montgomery’s sturdy language and the vast supplies he had at his disposal. Montgomery stated later, contradicting his earlier words, that it had never been his intention to capture Caen that soon. He argued that by his attacks he had tied down enough German units to enable the Americans to effect a break through elsewhere in Normandy. Many Americans were angered by the fact that the complacent Montgomery never acknowledged that a campaign did not proceed according to his plans. Eisenhower blamed him for always waiting for maximum logistical support and supplies before undertaking anything. Because he always waited so long, the Germans had the opportunity to bring up re-inforcements, hence the battle took longer than had been necessary.

On July 18th, 1944, Operation Goodwood was launched, the enterprise Antony Beevor typifies as "the most remarkable example of very sturdy language and very cautious action of Montgomery’s entire career." Montgomery boasted he would score a larger victory with this operation than at El Alamein in November 1942. His final orders to General Miles Dempsey, commander of the British 2nd Army and Lieutenant general Richard O’Connor, commander of VIII Corps, part of 2nd Army, were a lot less heroic. They received orders to advance one third of the distance to Falaise and then to look how the land lay. The attack was delayed because the tanks had to advance through narrow passages in a minefield that had been laid by the 51st Highland Division. Because the tanks lacked infantry support, they suffered heavy losses when they were shelled by camouflaged anti-tank guns. Next they had to endure a fierce counter attack by the 1. SS-Panzer division Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler. The 11th Armored Division lost 125 tanks that day.

Next day, the Canadians did manage to make some progress. When the weather changed and it started to rain heavily, Montgomery called off the attack. The Americans got the impression they had to run the gauntlet and that Montgomery was just muddling along. The only positive result of the operation was that the Germans assumed the main attack for the outbreak out of Normandy would be launched in the direction of Falaise. As a result, Operation Cobra (an attempt to break out of Normandy to the west), launched on July 25th in de direction of St. Lô and commanded by Lieutenant general Omar Bradley was not taken seriously in time. Partly because of this, this operation was successful. It was originally intended that Cobra, Goodwood and Atlantic, the Canadian part of the attack, would be launched on the same day. Forced by bad weather however, Bradley postponed the operation for a few days. As most of the German troops were concentrated in Montgomery’s sector, the Americans could rather easily effect a break out. If the German armor had been transferred to the American sector instead, the outcome may well have been very different. Tedder, Eisenhower’s Chief of Staff who strongly despised Montgomery, requested Eisenhower a few times during the battle in Normandy to fire Montgomery. Tedder, who was in charge of planning of the Allied Expeditionary Air Force, was particularly aggrieved because he had not received the airfields in Normandy he had been promised.

On August 6th, 1944, Hitler forced Generalfeldmarschall Günther von Kluge to launch a counter attack with three armored divisions near Mortain and reach Avranches in order to cut off Patton’s 3rd Army. The attack was repulsed however and the Allies embarked on a gigantic operation of encirclement. The German 5. Panzerarmee and 7. Armee were in an area, bordered by Mortain in the west, Falaise in the north and Argentan in the south. For a number of reasons, this Falaise pocket was not entirely closed off. The main reason was that Bradley, now commanding 12th Army Group and Montgomery, in command of 21st Army Group failed to maintain good communications and to set priorities. Montgomery approved a short encirclement near Falaise but, convinced as he was that 1st Canadian Army would break through soon, he had not assembled enough troops. He wanted to push to the Seine and used the better part of the troops available to him for that purpose. In his mind, he could always fall back on a long encirclement, trapping the Germans on the banks of the river. Bradley would not permit Americans to cross the line between Argentan and Falaise. XV Corps, commanded by Major general Wade Haislip could have closed the gap between Argentan and Falaise from Le Mans immediately but this was not permitted however. It should be noted that it is not certain that these troops were strong enough to successfully carry out such a risky attack. The result was that the neck of the Falaise pocket remained partly open for six days, enabling an estimated 150.000 Germans to escape. Later on, Bradley himself wrote about this: "It was partly this fear of running head-on into a single British division at Falaise that had induced me to halt Patton’s forces at Argentan."

Definitielijst

- D-Day

- The day of the long awaited invasion of western Europe in Normandy, France, 6 June 1944. After a long campaign of deception the allies attacked the coast of Normandy on five beaches to begin their march on Nazi Germany. Often explained as Decision Day, though this is entirely correct. The D stands for Day as generally used in military language. In this case it means an operation beginning on day D at hour H. Hence “Jour J“ in French.

- El Alamein

- City in North Egypt. The Battle of El Alamein took place from October to November 1942 and was a turning point in the war. The German-Italian advance in North Africa was finally halted by the Allies.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Leibstandarte

- Elite troops, originally Hitler’s body guards. Starting as a motorized infantry regiment it grew into a Panzer division.

- moral

- The will of the troops/civilians to keep fighting.

Images

Meeting of the Allied supreme command on February 1st , 1944. F.l.t.r.: Omar Bradley, Bertram Ramsay, Arthur Tedder, Dwight Eisenhower, Bernard Montgomery, Trafford Leigh-Mallory, Walter Bedell Smith. Source: Imperial War Museum.

Meeting of the Allied supreme command on February 1st , 1944. F.l.t.r.: Omar Bradley, Bertram Ramsay, Arthur Tedder, Dwight Eisenhower, Bernard Montgomery, Trafford Leigh-Mallory, Walter Bedell Smith. Source: Imperial War Museum. June 8th , 1944, Montgomery sets foot ashore in Normandy, after having been landed by a DUKW amphibious vessel. Source: Imperial War Museum.

June 8th , 1944, Montgomery sets foot ashore in Normandy, after having been landed by a DUKW amphibious vessel. Source: Imperial War Museum. The first encounter on French soil between Montgomery and his colleagues Omar Bradley (left) en Miles Dempsey (right). Source: Imperial War Museum.

The first encounter on French soil between Montgomery and his colleagues Omar Bradley (left) en Miles Dempsey (right). Source: Imperial War Museum.Operation Market Garden

Once the situation had been stabilized and Eisenhower had established his HQ on mainland Europe, he would take over command of all Allied ground forces. On September 1st, 1944, Montgomery’s command was limited to just the 21st Army Group consisting of the British 2nd Army, commanded by General Miles Dempsey and the Canadian 1st Army, commanded by General Harry Crerar. Montgomery was very aggrieved about this move, although this had always been intended from the beginning. The British press also criticized the changes within the Allied command structure. The British apparently ignored the fact that the American war efforts were significantly greater than those of Great Britain and the change of command had always been part of the planning for Operation Overlord.

After the Allied beakouit from Normandy, the units of the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS were put to flight and the Allied armies advanced rapidly. According to historian Robin Neillands, Montgomery's advance through France and Belgium showed that he mastered the military aspect of the pursuit as well as his American colleague Lieutenant General George Patton. Montgomery was promoted to Field Marshal on September 1st, 1944. The American commanders (especially Patton and Bradley) were not happy with this promotion, because in theory, it gave Montgomery a higher rank than Eisenhower.

Montgomery doubted Eisenhower’s capabilities. He wrote to the British Chief of Staff, Sir Alan Brooke: "Eisenhower is useless as commander of the ground forces, no discussion possible. He is totally and utterly useless. He knows nothing about warfare." Montgomery also criticized Eisenhower for his "broad front tactic," an offense with all Army Groups in the direction of the River Rhine. Montgomery advocated a narrow front strategy. He was of the opinion that there was no coordination worth speaking of in case of a broad front. Eisenhower argued that in case of a narrow front, the enemy would know exactly where to deploy his strongest defense, moreover, a narrow penetration would be vulnerable to flank attacks. Eisenhower probably also chose the broad front tactic, as it allowed him to keep both Bradley and Montgomery happy. Neither commander, who Bedell Smith characterized as prima donnas, probably would have accepted if the other had been given priority.

During September 1944, problems with supply of the Allied armies in Europe increased steadily. The supply lines from Normandy grew longer and longer and the other French Channel ports had still not been captured by 1st Army. Montgomery had captured the port of Antwerp with his 2nd Army though but he had failed to clear the Scheldt immediately afterwards. This enabled the Germans to re-inforce their garrisons on Walcheren and in the rest of Zeeland. Montgomery gave little priority to clearing the river, knowing the importance of the port of Antwerp. Ultra warned several times that the Germans were fortifying the Scheldt estuary with troops and equipment. However, Montgomery did nothing with this information. Historian Max Hastings writes: "The fact that the little British Field Marshal ignored intelligence that left nothing to be desired was a major cause of the failure of the Western Allies to penetrate into the heart of Germany as early as 1944." During the battle for the Scheldt, aimed at clearing the mouth of the river of Germans, the Canadians lost 12,800 dead and injured. The first Allied vessel would berth in Antwerp harbor as late as November 26th, 1944.

The Allies would have liked very much to end the war before Christmas and in late August this seemed possible indeed because of their speedy advance. Montgomery had been toying with the idea of deploying the newly established First Allied Airborne Army for some time, for example on Walcheren or near Wesel. Finally, he came up with a daring plan. The idea was to take the bridges over the Maas, Waal and Rhine at Arnhem and Nijmegen by airborne landings by a total of three Airborne Divisions in the Netherlands and then push through to the heart of Germany. On September 10th, Montgomery and Eisenhower met at Brussels airport. Before beginning, Montgomery demanded all staff members of Eisenhower leave the aircraft.

Beevor described the ensuing meeting this way: Montgomery took a bundle of telegrams from his pocket, waved it and asked, "Did you send it to me?" Yes, of course," Eisenhower replied. "Why?" "Well it's all bullshit, bullshit." Eisenhower waited until Montgomery was silent; then he leaned over, put his hand on Montgomery's knee and said, "Steady, Monty, you can't speak to me like that. I'm your boss. Montgomery muttered, "I'm sorry, Ike." Then Montgomery reproached the commander in chief that his 21th Army Group was not given absolute priority. He also denounced the broad front strategy pursued by Eisenhower and presumptuously defended his plan for Operation Market Garden.

Later on, Eisenhower wrote about this meeting: "Today it is exactly 15 years ago that I met Monty at Brussels’ airport. He made this absurd proposal to push on to Berlin like a stroke of a dagger. I asked him to reach the River Rhine first and granted him everything he asked for. Then I told him to end all hostilities in Antwerp, due to the shortages in our supplies and the absolute necessity to capture the port in order to normalize our supply system. He even failed to establish a bridgehead."

Operation Market Garden was a very audacious plan which was entirely out of Montgomery’s character, as he usually followed a cautious, calculating and wait-and-see strategy. Omar Bradley wrote: "If the straight-and-narrow teetotaler Montgomery had stumbled into SHAEF with a hangover, it could not have surprised me more than this daring adventure he proposed." Bradley and Patton did not agree with the operation and pointed out the risks. For this operation, Montgomery demanded all possible supplies and re-inforcements. As far as he was concerned, 12th Army Group commanded by Bradley would have been completely bled dry but this went a little too far for Eisenhower. Fact was that Bradley and Patton encountered problems by the decreased supply, causing them to curb their offensive actions, something which evoked much vexation in Patton.

The operation was launched on September 17th, 1944. Market Garden however did not result in the success that had been expected. The operation failed mainly because the drop zones were too far away from the targets, radio communication did not function and the Germans reacted much faster than had been anticipated. Reports about German armored divisions in the vicinity of Arnhem were ignored by the Allies. XXX Corps, commanded by Brian Horrocks failed due to stiff German resistance and the fact they had to advance from Neerpelt (a town on the Dutch-Belgian border) through a narrow corridor in order to reach the bridge at Arnhem on time. Despite heroic conduct of all participating troops, the paratroops in Arnhem were forced to surrender on September 21st , the general retreat from Oosterbeek began on September 25th, (Operation Berlin). The injured surrendered in Oosterbeek on September 27th. Hastings describes Market Garden as an incredibly irresponsible move and a deserved stain on Montgomery's reputation. Beevor labels Market Garden as a very bad plan from the outset and from above. He also accuses Montgomery of not showing any interest in the tactical problems surrounding airborne operations. Although Montgomery himself never admitted this, Operation Market Garden was in fact his first defeat. He even said at one point that the operation was 90 percent successful, because they had managed to cover nine-tenths of the route to Arnhem. To this, Arthur Tedder mockedly commented, "If you jump off a cliff, you'll have an even higher success rate...to the last few inches above the ground." Montgomery further argued that the defeat was due to a shortage of supplies and support. This argument referred to absolutely nothing: Montgomery had received a maximum of support, to the disadvantage of other armies. Or, in the words of historian Ingrid Baraître: "If he had wanted even more, we should have acquired weapons, troops and fuel from the enemy." Montgomery further pointed to the Poles as a scapegoat for the fiasco in Arnhem and Oosterbeek. He stated that the 1st (Polish) Independent Parachute Brigade under Stanislaw Sosabowski had refused to fight. Historian Neillands describes this as a very unjust accusation: after their drop at Driel the Poles had fought very hard and bravely and partly because of the occupation of the crossing the men of the British 1st Airborne Division could be evacuated across the Lower Rhine.

After the failure of Market Garden, Montgomery continued defending the narrow front strategy and urging for absolute priority for his 21st Army Group. He partly had his way in this. He received additional supplies to clear the mouth of the Scheldt. He also received, together with Bradley, joint responsibility for the the American 1st Army. Montgomery was not satisfied and frequently criticized Eisenhower; he claimed to be better suited as supreme commander of the ground forces. Eisenhower responded Montgomery had better get busy with the capture of Antwerp harbor. Eisenhower also blamed him for thinking in nationalities too much. The Supreme Allied Commander further stated that if Montgomery did not agree with the orders he had been given. Eisenhower would refer the matter to a higher authority, the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Since the generals of the highest command were behind Eisenhower, it would likely result in the British being replaced. Montgomery apologized and said he had only voiced his opinion. During a staff meeting with Marshall, Montgomery again complained about the command structure, arguing Eisenhower had too little control over the situation and failed to set priorities. Montgomery thought a ground commander should be appointed , himself or Bradley. He indicated that he would not bring up the point of command again, but he did not comply. On November 30, 1944, the Field Marshal wrote to Dwight Eisenhower indicating that the offensives of Omar Bradley and George Patton had failed to achieve any of their goals from October-November, in which he was right, due to fierce German opposition Too bad the armies hadn't advanced as far as planned. He used this fact to make the presumptuous point once again that there should be an overall commander for the ground forces and that he was best suited for that purpose.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- SHAEF

- Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, the Allied High Command in Western-Europe after the Normandy landings.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

- Ultra

- British intelligence service during World War 2

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Montgomery crosses the Rver Seine in France in his Humber staff car, September 1st, 1944. Source: Imperial War Museum.

Montgomery crosses the Rver Seine in France in his Humber staff car, September 1st, 1944. Source: Imperial War Museum. Prior to Operation Market Garden, Montgomery studies a map with Lieutenant-General Brian Horrocks (commander of het XXX Corps) and Prince Bernard. Source: Imperial War Museum.

Prior to Operation Market Garden, Montgomery studies a map with Lieutenant-General Brian Horrocks (commander of het XXX Corps) and Prince Bernard. Source: Imperial War Museum.The last year of the war

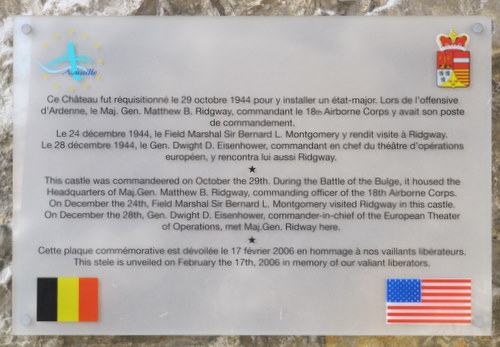

On December 16th, 1944, the Germans launched a surprise attack through the Ardennes. The Germans attacked in a weakly defended sector of the front and scored some successes in the first days of the offensive. Panic prevailed among the Allies for a short time. On December 20th, Eisenhower called a meeting with his army commanders in order to cope with the awkward situation. As usual, Montgomery did not turn up in person and sent his Chief of Staff. One of the measures taken by Eisenhower was to place 1st and 9th Army under temporary command of Montgomery. Eisenhower argued that 12th Army Group’s HQ was isolated in Luxemburg and Montgomery could be in constant touch with both armies. Bradley however considered this measure a motion of distrust and threatened to resign.

Montgomery created the impression the Americans could not cope any longer and that he was called upon to save the day. The other measure taken was that Patton and his 3rd Army would attempt to relieve the 101st Airborne Davison trapped in Bastogne. Patton himself said about this: "Neither the weather, nor the enemy, nor Montgomery will endanger 3rd Army’s mission towards the Ardennes." When asked if he had a message for the field marshal he answered: "Tell Montgomery 3rd Army will strike north and he’d better get out of the way as I will put the German army on to him.".

On December 27th, after a 90 degree turn and an advance of 112 miles from the Saarland to the Ardennes, Patton and his 3rd Army managed to relieve the encircled 101st Airborne Division in Bastogne. Despite requests from Eisenhower and Bradley, Montgomery refused to attack westwards. He wanted to regroup his forces first and he feared a German counter attack. In the Ardennes, the field marshal lost all respect of the Americans. Montgomery again demanded supreme command of all Allied ground forces in a letter to Eisenhower and he voiced criticism on the Americans and the broad front strategy. Subsequently, Eisenhower drew up a letter to the Joint Chiefs of Staff stating he would resign, provided Montgomery would be replaced, preferably by Harold Alexander. Only through mediation by Montgomery’s Chief of Staff, Lieutenant general Freddy de Guingand his discharge was prevented. Montgomery apologized and indicated Eisenhower could tear up his previous letter.

On January 3rd, 1945, after long urging, Montgomery took up the offensive. He managed to score some successes with 1st Army in the vicinity of Houffalize. On January 7th he called a press conference at his HQ in Belgian Zonhoven. He claimed the leading role for himself and argued he had halted the offensive and that the British had made the largest contribution, totally ignoring the fact that Patton and his 3rd Army had broken the encirclement of Bastogne in the south and Montgomery, despite many promises of attack, had waited very long before launching an attack in the north. He said about the Americans they were fine soldiers but it seemed like he was insinuating that they could excel only under his command. Churchill was very much aware of the detrimental consequences of Montgomery’s behavior and he delivered a speech in Parliament on January 18th , indicating that the Americans had done most of the fighting in the Ardennes and the British contribution had been small. He also indicated that no part should be claimed for the British army in what undoubtedly had been the largest American battle of the war.

Montgomery’s unamicable and headstrong attitude created more and more friction among the Americans. On January 17th, 3rd and 1st Army met at Houffalize. In consequence, 1st Army was placed under command of Lieutenant general Bradley again. Until the River Rhine had been crossed, 9th Army remained under command of the 21st Army Group. Montgomery was ordered to advance in the northern sector in the direction of the Ruhr Valley. He also demanded additional troops and a leading role in the crossing of the Rhine. Montgomery received American re-inforcements but in the end, units of 1st Army would be the first to cross the river at Remagen on March 7th. In February, Montgomery launched Operation Veritable southeast of Nijmegen. German resistance was very strong and the muddy terrain presented an obstacle to the advancing troops. The offensive was successful however as the the left bank of the Rhine was captured.

On March 30th, 1945, Montgomery was ordered to advance towards Hamburg and Denmark. He had hoped he would be allowed to capture Berlin but Eisenhower left the city to the Russians. Later on, the 21st Army Group advanced towards Denmark. Montgomery seemed to have lost his fighting spirit. He was very disappointed he had not been allowed to capture Berlin. Bradley, as mentioned earlier, who could not get along well with him had the feeling Montgomery had lost his appetite for the war. Eisenhower had to ask the field marshal frequently to hurry up in order to prevent the Russians from pushing through to Denmark. On May 4th, 1945, on the Lüneburger Moor, Montgomery accepted the unconditional surrender of all German troops in the Netherlands, northwestern Germany and Denmark. On May 7th , the definite surrender of the Third Reich was signed in Reims, the truce became effective the next day.

Definitielijst

- marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

Images

Montgomery, with the American generals Collins and Ridgeway, during the offensive in the Ardennes. Source: U.S. Army Center of Military History.

Montgomery, with the American generals Collins and Ridgeway, during the offensive in the Ardennes. Source: U.S. Army Center of Military History. Premier Churchill, Montgomery, Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke and the American general William Simpson look at the so called "dragon’s teeth" of the Siegfriedline near Aachen, March 4th , 1945. Source: Imperial War Museum.

Premier Churchill, Montgomery, Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke and the American general William Simpson look at the so called "dragon’s teeth" of the Siegfriedline near Aachen, March 4th , 1945. Source: Imperial War Museum.After the war

Next, Montgomery was appointed commander of the Army of the Rhine, the British occupation force in Germany. On June 8th, 1945, Montgomery sent a letter to Eisenhower in which he wrote: "Now that everyone goes his own way, I want to inform you what honor and privilege it has been for me serve under you. I have much to thank you for. I am well aware I have shortcomings and that I was not an easy subordinate. I do prefer to go my own way but you have kept me on the right track in difficult and trying times and I learned a lot from you. For that and everything you have done for me, I am very grateful to you."

On January 1st, 1946, the honorable title of Viscount Montgomery of El Alamein was bestowed on him and he was appointed Chief of the Imperial General Staff, the highest military rank in Great Britain. In this function, he also created friction by not showing up at meetings and his collisions with Arthur Tedder who had been appointed Chief of the Air Staff. Consequently, Montgomery held this position up to 1948 and then he was named chairman of the permanent defense organization of the West-European Union. In this capacity he was also involved in the establishment of NATO in 1946. As deputy commander of the armed forces of this organization, he served under Eisenhower again who had become president of the United States in the mean time.

In 1958 Montgomery relinquished all his commands and his memoires: The Memoires of Field Marshal Montgomery were published. In it he heavily criticized general Eisenhower concerning the strategy that was applied during the landings in Normandy and about his leadership of the remainder of the campaign in Europe. This was the reason all contacts between Eisenhower and Montgomery were severed. In a letter to Lord Hastings Lionel Ismay (in war time the Chief Staff Officer and in that capacity Churchill’s military advisor), dated January 14th, 1959, Eisenhower vented his venom about Montgomery. He blamed Montgomery for having waited too long before advancing out of the Catania plain and the long and unnecessary dawdling before crossing the Strait of Messina in July-August 1943.

Eisenhower also blamed the field marshal for his big promise on the eve of D-Day concerning the capture of Caen and the break out southward which finally resulted in hardly anything. He also criticized Operation Market Garden. He typified it as a ridiculous proposal and blamed Montgomery for having achieved nothing, although Eisenhower had given him everything (supplies and men) he had asked for. He ended with: "I cannot forget how he was always ready to belittle associates at the critical moments when everybody’s cooperation was urgently needed. Therefore I personally think that historians will not be tempted to portray him too gloriously on these grounds alone, even when his memoires had not unveiled some of his praiseworthy features."

Between 1951 and 1966 Montgomery was chairman of the board of directors of St. John’s School in Leatherhead, Surrey. In 1953, in Hamilton, Canada, the Viscount Montgomery Elementary School was opened in his honor. For his conduct during World War Two, Montgomery was, among others, awarded the "Grootkruis in de Orde van de Nederlandse Leeuw" (Grand Cross of the Order of the Dutch Lion), the Grand Cross of The Most Honorable Order of the Bath, the Russian Orden Pobeda and the Polish Order Virtuti Militari Grand Cross. A portrait of his is on display in the Portrait Gallery and a statue of the field marshal stands in front of the British War Department.

Even after the war, Montgomery continued to cause controversy. After a visit to South Africa for instance, he spoke favorably about the system of apartheid. He also spoke positively about Mao Che Tung, China’s leader from 1949 to 1976 and one of the greatest mass murderers of the 20th century.

Montgomery passed away on March 24th, 1976 at the age of 88 in his house Isington Mill in Isington, Hampshire. He was buried in the Holy Cross Cemetery in nearby Binsted.

Definitielijst

- D-Day

- The day of the long awaited invasion of western Europe in Normandy, France, 6 June 1944. After a long campaign of deception the allies attacked the coast of Normandy on five beaches to begin their march on Nazi Germany. Often explained as Decision Day, though this is entirely correct. The D stands for Day as generally used in military language. In this case it means an operation beginning on day D at hour H. Hence “Jour J“ in French.

- El Alamein

- City in North Egypt. The Battle of El Alamein took place from October to November 1942 and was a turning point in the war. The German-Italian advance in North Africa was finally halted by the Allies.

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

Images

Epilogue

According to most historians, Bernard Montgomery was well schooled in tactics and strong in the field of military planning. He was adored by the lower ranks, more so because he took few risks. He liked to remain as close to the front line as possible and he was, according to many a soldier among soldiers who was able to restore the situation in armies where morale had been dented. After the war German generals named Patton and Montgomery as the best they had faced in battle.

In the foreword to his memoires, Montgomery wrote he had always acted according to his own convictions, his duties and his conscience. He admitted he was controversial but he also argued he had never sought the acknowledgment of others. The historian Neillands recognizes the negative qualities of the Field Marshal. He characterizes him as vain, dictatorial, obsessive, a real test for his colleagues and superiors and as someone who was not always close to the truth. "On the other hand, Montgomery was popular with his soldiers, endearing to his subordinates, able to admit mistakes, loyal to his allies, and an experienced and professional general." Others were less nuanced about the Field Marshal and dismissed him as a chatterbox. After a visit to the Dutch Princess Irene Brigade in early 1944, one of the soldiers remarked: "If he talks as much as he fights, the war can last a long time." The final sentences of Montgomery's memoires read as follows: "Many impressions will accompany me in the autumn of my life but the one thing I will cherish most, above all other things, is the image of the British soldier. Strong and tenacious in times of hostilities but pleasant and gentle in times of victory. It is these men to whom our Nation owes, again and again, her safety and her honor in times of adversity."

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

Images

Information

- Article by:

- Wesley Dankers

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

- 12-'42: Victor of the Battle of Egypt

- 04-'43: How Montgomery Captured the Mareth Line

- 06-'44: After Four Long Years D-Day Dawns at Last

- 07-'44: The Battle Fronts

- 07-'44: I Was There! - I Saw a City Below the Germans' 'West Wall'

- 08-'44: The Bailey Bridge that Triumphs over Demolitions

- 01-'45: How the Army's Amazing Bailey Bridge is Built

- 02-'45: I Was There! - British Fought Like Tigers at the Ardennes Tip

- 03-'45: I Was There! - It's a Watery War on Our Part of the Front

- 05-'45: Dramatic Last Days of the War in the West

- 05-'45: My Visit to Wartime Holland

- 06-'45: Along the Crowded Roads of War

- 07-'45: Men of Destiny Who Govern Occupied Germany

- 07-'45: Our Diary of the War

- 11-'45: Now It Can Be Told! - Monty's D-Day Bluff Foxed the Germans

- 12-'45: Americans' S.O.S. on D-Day

- 01-'46: Now It Can Be Told! - Whitehall's Wireless Link With the War

- 02-'46: Now It Can Be Told! - D-Day Rehearsal at Cambridge University

- 12-'46: The Daring Raid on Rommel's H.Q.

The War Illustrated

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- BARAITRE, I., Eisenhower en zijn generaals, Lannoo, Tielt, 2008.

- BEEVOR, A., De Slag om Arnhem, Ambo Anthos, Amsterdam, 2018.

- BEEVOR, A., De Tweede Wereldoorlog, Ambo|Anthos, Amsterdam, 2012.

- HASTINGS, M., De geheime oorlog, Hollands Diep, Amsterdam, 2015.

- NEILLANDS, R., De slag om de Rijn, Uitgeverij BZZTôH, Den Haag, 2007.

- ROBERTS, A., Churchill, Prometheus, Amsterdam, 2019.

- ROBERTS, A., Legendarische veldheren III, Omniboek, Utrecht, 2011.

- THOMPSON, R.W., Bernard Law Montgomery, Just Publishers, Meppel, 2008.

- ZEE, H. VAN DER, In Ballingschap, De Bezige Bij, Amsterdam, 2005.