Introduction

John Dutton Frost (Poona, India, 31 December 1912 - West Sussex, England, 21 May 1993) was a British officer that as lieutenant-colonel tried to conquer the Rhine Bridge in Arnhem in 1944.

Frost was born in Poona (India) as the son of General Frank Dutton Frost, who at the time served in the British-Indian army. Before WWI the family returned to England. During WWI his father served at the front and received several military honours. After the war, Frost’s father was posted to the British mandated territory of Mesopotamia (currently Iraq). Here John learned the Arabic language. In 1921 the family again returned to the UK. Frost studied at the Royal Military Academy in Sandhurst and served at the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles).

Definitielijst

- mandated territory

- Former German colonies and Turkish territory which was governed on behalf of the league of Nations after World War 1.

Images

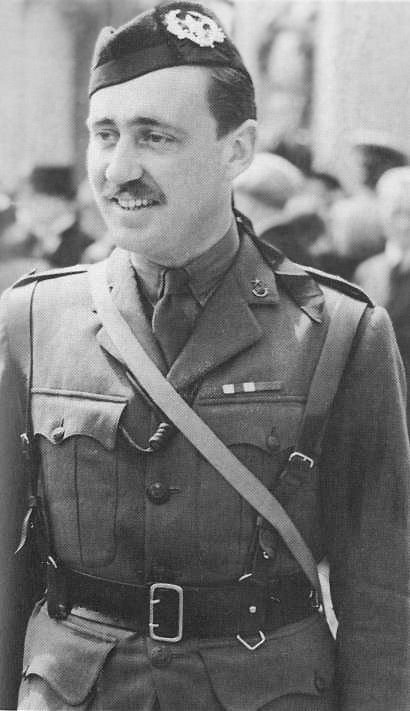

John Frost Source: The Pegasus Archive.

John Frost Source: The Pegasus Archive.First years of war

In 1938, Captain Frost was stationed in Iraq. He was still stationed there at the outbreak of the Second World War. When his contract ended in the summer of 1940, John requested if he could return again to the Cameronians, but his request was denied, because his knowledge of the Arabic language was too valuable for the army. Frost made it very clear that he did not agree with this decision. He finally received the order to report to the 10th Battalion of The Cameronians. He received a copper hunting horn from the hunting club 'Royal Exodus Hunt' as a farewell gift.

Unfortunately, his return to the Cameronians ended in disappointment. The battalion was mainly deployed for coastal defend duties, so there was hardly any action. When a request came through for Captains to join the newly founded 11th Special Air Service Battalion, as company commander, Frost didn’t waste a minute and reacted immediately. This special commando unit of parachutists was led by Major David Stirling. Just ten days later, he was already training together with this new unit. After having done five parachute jumps in three days, he received his parachute certificate and took on command of C Company.

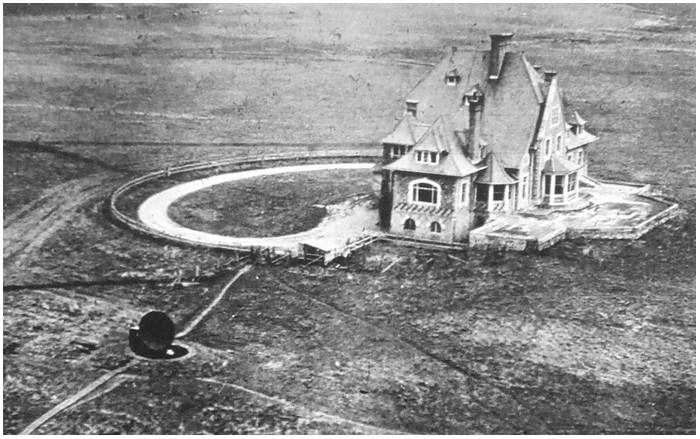

John Frost was promoted to Major and together with his C Company they were selected to perform the famous Bruneval Raid (Operation Biting) on 27 February 1942. The operation, an attack on a radar installation on the north Normandy coast, aimed at stealing vital components of the new German radar system, became a great success. Frost’s company was dropped by parachute and once the operation was completed they were evacuated by plane by the Allies. His men succeeded in steeling the secret German equipment, which could be examined in England. What remained of the radar installation was blown up. All but eight men were taken off the beach by landing craft which were waiting for them. For his performance during this mission, Frost was rewarded the Military Cross (a British military honour for heroic performance or credible combat actions) on 5 May 1942.

Not much later, he got command of the 2nd Battalion of the 1st Parachute Brigade of the 1st Airborne Division and left for Africa. His first mission in North-Africa was during Operation Torch: destroying enemy planes on an airfield nearby Depienne (Tunisia) on 19 November 1942. When John Frost and his men were dropped nearby the airfield, they did not find any planes. What they did encounter, however, were six heavy tanks. The tanks immediately opened fire and Frost’s small unit was also being attacked from the air. The following morning, the German force was reinforced with infantry, causing the battalion of Frost to sustain more losses.

Lieutenant Colonel Frost left behind a small group of soldiers to protect the heavily injured. He blew his hunting horn to gather the remaining troops and withdrew to Medjez (Tunisia). Although Frost found himself surrounded by a large German force, he managed to escape with a large part of his battalion. Together with around 120 men he safely reached allied lines after a long journey of approx. 150 kilometres through enemy territory.

Frost was upset about the failing intelligence service, but his anger faded when he heard that because of his action, many hostile troops were drawn away from a large battle between the Allies and the Germans. On 11 February 1943, John Frost received the Distinguished Service Order (a British reward for officers who performed praiseworthy work during war time or who distinguished themselves on another level) for his bravery and level-headed performance under heavy fire and difficult circumstances.

A couple of weeks later the 2nd Battalion came under attack by a combined force of artillery and infantry. Despite the losses he had already sustained, Frost managed to ward off the enemy. The 1st and 3rd Battalion joined forces with Frost, and together they almost managed to capture the famous German parachutist commander Rudolf Witzig.

During the four months that the brigade spent in Africa, it had fought almost without interruption. Many soldiers were injured and the brigade mourned the loss of more than 1500 men. It was during this time that the soldiers of the 1st British Airborne Division got their nickname ‘the Red Devils’ (Rote Teufel) from the Germans.

During the push in North-Africa, Frost earned a reputation of being a very competent commander. Sergeant General Gerald Lathbury, commander of the 1st Parachute Brigade, said about him: "He had a very relaxed leadership style. Outside the battles, he left matters most to his brigade commanders, but in action you could always find him on the forefront and he seemed to be five years younger."

On 13 July 1943 Frost and his 1st Parachute Brigade were part of ‘Operation Fustian’ as part of the allied invasion of Sicily. The goal of Operation Fustian was to conquer the Primosole bridge over the Simeto river in East Sicily. The brigade had to land on both sides of the bridge, conquer it and secure the immediate vicinity. This position had to be held until the ground troops, that had landed a few days earlier, would arrive.

The operation did not go without problems. Many aircraft with parachutists aboard were shot down and the parachutists that could be dropped, landed miles away from the desired landing zone. Despite the setbacks and the resistance of the German and Italian troops, the airbornes managed to conquer the bridge.

The hostile force became ever stronger and the Allies did not manage to join the paras before nightfall. Due to the increasing number of casualties and the growing shortage of supplies, Sergeant General Lathbury decided to withdraw. In the end, the reinforcement troops succeeded in reconquering the bridge after several days of battle.

The 1st Parachute Brigade was not deployed again for the advance into Sicily, but instead returned to Malta. After being deployed for a while at the landing at Taranto on the South-Italian mainland (Operation Slapstick) the unit returned to England in September 1943 to undergo training for future operations in North-West Europe. The 2nd Battalion was accommodated in Stoke Rochford, nearby Grantham, Lincolnshire.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- Raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

A photo of the target from the raid on Bruneval. The german radar is visible left on the foreground. Source: Strijdbewijs.

A photo of the target from the raid on Bruneval. The german radar is visible left on the foreground. Source: Strijdbewijs. John Frost (right) on his way back after the raid on Bruneval. Source: Strijdbewijs.

John Frost (right) on his way back after the raid on Bruneval. Source: Strijdbewijs. John Frost after the presentation of an award for his part in the raid on Bruneval. Source: Wikipedia.

John Frost after the presentation of an award for his part in the raid on Bruneval. Source: Wikipedia. A map from operation Fustian. Source: The Pegasus Archive.

A map from operation Fustian. Source: The Pegasus Archive. The bridge at Primosole after he was captured by the allied forces. Source: Imperial War Museum.

The bridge at Primosole after he was captured by the allied forces. Source: Imperial War Museum.Market Garden

After the success of the Normandy invasion, at which the 1st British Airborne Division was not deployed, the Allies quickly advanced through France and Belgium. In that time, many plans were being devised for operations to be carried out by the division, but none of those plans became reality. This changed with operation Market Garden. Frost and the other officers of the brigade were told on 15 September 1944 that they had to prepare themselves for an offensive in the Netherlands with the goal to conquer the Ruhr district, in order to eliminate the German war industry.

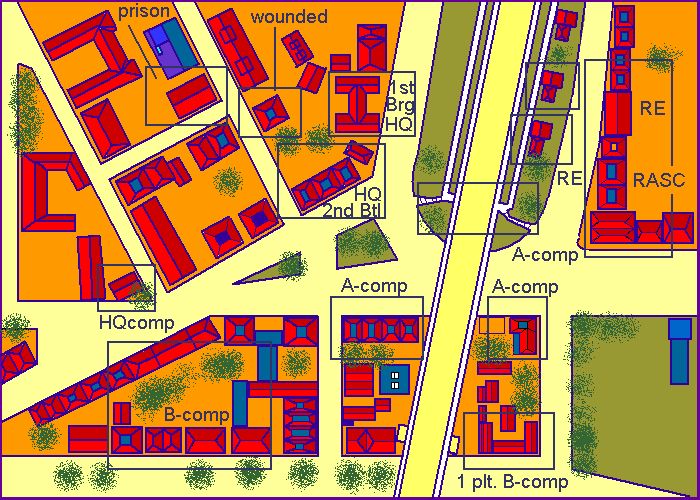

The task of the parachutists and the airborne troops was to lay a proverbial carpet in the Dutch provinces of North-Brabant and Gelderland on which the ground troops of the 30th Corps could march to the Ruhr district. The vital positions that were captured and had to be retained, were the bridges over the rivers Maas, Waal and the Lower Rhine. The 1st British Airborne Division was assigned the task to conquer the bridges in Arnhem. The 2nd Battalion of Frost, complemented with among others the brigade headquarters, a unit of six pound anti-tank artillery (Royal Artillery) and a number of Royal Engineers had to take the Southern route – the road besides the Northern bank of the river Rhine (code name ‘Lion’). It was their job to occupy the rail bridge at Oosterbeek and the road bridge at Arnhem and one company had to take up a line of defence on the South bank of the river at the road bridge.

The main concern of Frost was the fact that the landing zones of his battalion were located more than ten kilometres to the West of the bridges, causing the surprise element to be lost. Besides this, only one landing per day would take place, resulting in any reinforcements to arrive only a day later. Frost became less concerned when he was assured that he would only face minimal German resistance. In fact, John Frost was so sure of a successful outcome of the operation that he assigned his batman, private Wicks, with the task to already place his shotgun, cartridges, smoking and golf clubs in the staff car that would follow.

Operation Market Garden started on 17 September 1944. Immediately after the landing on the heath nearby Renkum, Frost took out his hunting horn to blow the 'assemble' signal. He took his battalion through Doorwerth and Oosterbeek to Arnhem. The German resistance proved more severe than anticipated and the radio connections were bad. Things got worse: the rail bridge at Oosterbeek was blown up before their own eyes, which hampered a quick push, because citizens came flocking in in large numbers. Despite this, the first British airborne troops managed to reach the northern slip road of the bridge. Less than half of them were part of the 2nd Battalion. During the night and early-morning hours, ever more British airborne troops entered the zone. And, once B-company managed to free themselves from their positions near the pontoon bridge (nowadays the location of the Nelson Mandela bridge), they too were able to reach the northern slip road of the bridge. After that, the composition of the British remained more or less the same. In the early-morning hours of Monday 18 September, approx. 750 British were at the Arnhem bridge, but according to the plans, it should have been 2,000.

That night, Frost ordered a platoon from A-company, led by Lieutenant Jack Grayburn, to cross the bridge. They encountered heavy artillery from machine guns and a panzer, armed with a 20 millimetre rapid-firing gun. West of the northern slip road, a tower was located with a 2 centimetre Flak rapid-firing gun. Frost’s men were also fired at from this tower. Later that night, this bunker was destroyed by antitank artillery. A wooden shed, where explosives were stored, exploded after being hit by a British flame-thrower. Due to the explosion, the bridge temporarily caught fire, but the fire quickly extinguished by itself.

That night, units from the 1st company of the SS-Panzer-Aufklärungs-Abteilung 10 (1.(Pz.Späh) Kp.//SS-Pz.A.A.10) arrived in Arnhem. They were carrying out reconnaissance missions towards Emmerich, Nijmegen and Wezel after having received the first reports of hostile airborne landings. They did not encounter enemy troops, and were given the order to drive to Arnhem via Borculo and Eibergen. When they entered the road bridge, the immediately found themselves under fire. They responded in the same manner, but retrieved. Immediately, contact was made with the headquarters of the division in Velp, announcing that the Germans had lost possession of the bridge, and that the British were hiding in the houses surrounding the northern slip road of the bridge.

John Frost decided to create a perimeter with his men and wait for further enforcement troops. Initially, the perimeter was around 250 metre wide and about 270 metres long. Anti-tank artillery was positioned around the bridgehead and land mines were placed on the bank of the slip road. Moreover, machine guns were positioned on the top floors of the warehouses and other buildings.

That same evening, Frost and his men came under attack of the Germans. Following an initial bombarding with mortars, grenadiers – probably from the SS-Panzer-Aufklärungs-Abteilung 9 (SS-Pz.A.A. 9), - managed to reach the northern side of the bridge, protected by one or two panzers. The attack failed because of heavy British counter fire.

Later that evening, a couple of German trucks filled with German soldiers tried to cross the bridge towards Arnhem. This convoy too was stopped by the British. The trucks were destroyed and only two German soldiers survived this fight. The SS-Panzer-Aufklärungs-Abteilung 9, led by commander SS-Hauptsturmführer Viktor Eberhard Gräbner, took off in the night of 17-18 September from the Nijmegen area towards the southern slip road of the Arnhem road bridge.

Around 9 a.m. Gräbner’s convoy entered the bridge with top speed. In front were the fastest, armoured vehicles, consisting of 8-wheel panzers armed with a 2 centimetre Flak rapid-firing gun. These six panzers broke through the British defence line and drove through to the city centre of Arnhem.

In a much lower pace trailing behind these panzers were the armoured semi-caterpillar vehicles. The first one was destroyed by the British when a hand grenade was thrown onto it from above. The second vehicle was stopped by shooting the driver and the driver’s mate. This resulted in confusion with the German offensive power. And confusion got worse, when the third vehicle backed up in panic and bumped into the fourth vehicle. The two vehicles got entangled and were sitting ducks for the airborne troops. During this action two more semi-caterpillar vehicles were destroyed. All the German crew members were killed by British fire when they tried to abandon the vehicles. Three semi-caterpillar vehicles that succeeded in crossing the bridge, were taken out when they reached the positions of the British. A column of unarmoured trucks that was driving behind the semi-caterpillar vehicles was practically destroyed in its entirety. The German attack proved a total disaster: the bridge was littered with burning vehicles and there were many German casualties.

But the Germans managed to regroup themselves and in the afternoon they intensified the attack on the defence troops who were guarding the Arnhem bridge. The Germans were able to set fire to many of the buildings on the north side of the bridge, but the airborne troops did not falter. During the fight, the British cannons from Oosterbeek provided accurate firing support. The firing support was led by observation officers at the bridge. The positions were accurately shelled, which resulted in the break-up of many German attacks. After a day of battle, Frost concluded that their perseverance was being put to the test and that their supply of equipment was quickly diminishing.

In the early morning of 19 September, the situation for the British at the Arnhem bridge was questionable, but surrender was not considered an option. The troops under Frost’s command still had high moral and were responsible for heavy losses on the German side. His troops kept defending the northern slip road, waiting in vain for the allied ground troops coming from the south. The remainder of the 1st Parachute Brigade was also unable to join Frost’s men, because the Germans cut off the access path to the road bridge in increasingly large numbers.

This resulted in the airbornes at the bridge being ever more boxed in and they found themselves under constant fire from an ever growing and powerful German attack force. The attack force was made up of amongst others, troops from the 9th and 10th SS-Panzer-Division. Under cover by tanks, cannons and mortars the German infantry started sounding out the positions and infiltrating them. This resulted in fierce door-to-door fights with the bayonets also being used. The systematic destruction of buildings paralysed the defenders and was an absolute disaster for the wounded who were hiding out in basements. Due to the increasing number of wounded and a shortage of medical personnel and supplies, things went from bad to worse.

Despite the fact that there was no supply of weapons and food, the troops under the inspiring command of Frost, continued to fight. The determination of John Frost to carry out his order, was also apparent from his refusal of a Germen request to surrender. The defence of the northern slip road of the bridge was still continuing when Frost in the afternoon of Wednesday 20 September sustained a severe injury to his legs. Meanwhile his men continued to defend the bridge for twice as long as they were given the order for. On Wednesday evening they succeeded in contacting the division headquarters in Oosterbeek (located in hotel Hartenstein). Frost requested reinforcements, surgical teams, weapons and food.

Only after German tanks set the houses of the defenders on fire one at a time, defence started to crumble. When in the early morning hours of 21 September, also the house of the brigade commander – which provided accommodation to more than 200 wounded – was set on fire, the remaining forces of the original 750 airbornes were forced to surrender at the bridge. Frost’s men who in numbers was made up of no more than one battalion, managed to defend the north side of the bridge for another three days and four nights from continuous German attacks. John Frost was also captured and in the process lost his copper hunting horn.

Frost remained in captivity until the end of the war. First he stayed in the Oflag (prisoner of war camp for officers only) IX-A/H in the castle of Spangenburg in Hessen and later, when his ankle wound opened up again, he was transferred to a hospital for prisoners of war in Obermassfeld, Thüringen. Here he was freed in March 1945 by soldiers of the 3rd US Army of General Patton. For his part in the battle of Arnhem, John Frost received a clasp (presented to a holder of a Distinguished Service Order for an achievement that justifies a DSO) to put on his DSO decoration.

Definitielijst

- Abteilung

- Usually part of a Regiment and consisting of several companies. The smallest unit that could operate independently and maintain itself. In theory an Abteilung comprised 500-1,000 men.

- artillery

- Collective term for weaponry that fires projectiles. The modern term artillery mainly designates guns in general from which the range and calibres are outside certain boundaries. Artillery is also the name of the army unit which mainly operates such guns.

- brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Flak

- Flieger-/Flugabwehrkanone. German anti-aircraft guns.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- moral

- The will of the troops/civilians to keep fighting.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

Overview of the positions of the British units during the days of the battle at the northern ramp of the Arnhem bridge. Source: Strijdbewijs.

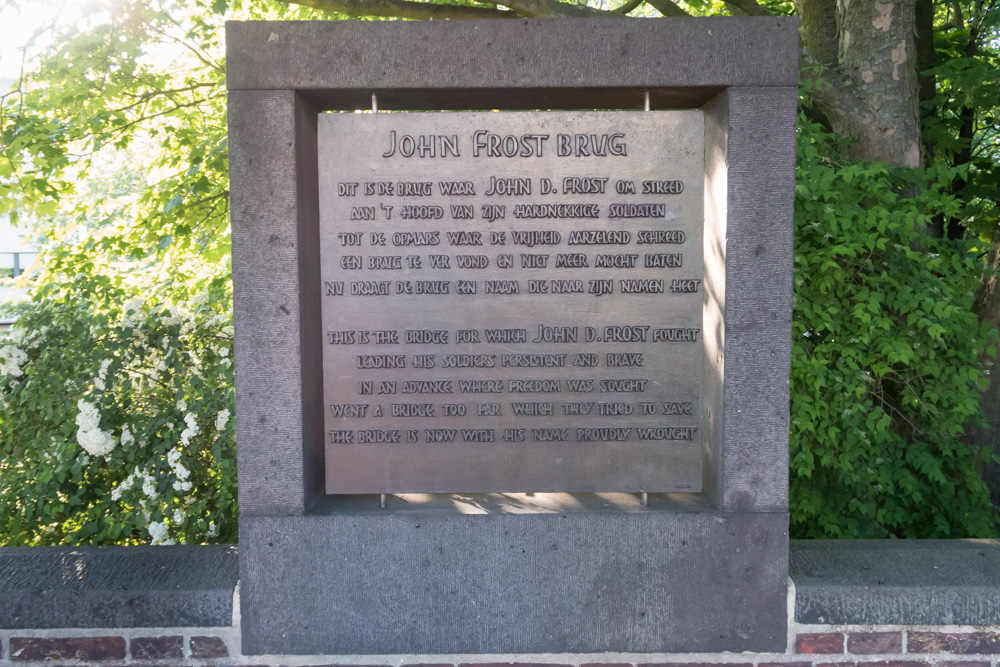

Overview of the positions of the British units during the days of the battle at the northern ramp of the Arnhem bridge. Source: Strijdbewijs. This plaque (Prinsenhof 1, Arnhem) indicates the place where was the headquarters of John Frost during operation Market Garden. Source: TracesofWar.com.

This plaque (Prinsenhof 1, Arnhem) indicates the place where was the headquarters of John Frost during operation Market Garden. Source: TracesofWar.com. The John Frost bridge at Arnhem. Source: Arjan Vrieze.

The John Frost bridge at Arnhem. Source: Arjan Vrieze.Post-war years

Frost’s hunting horn was recovered during clearing work of the rubbles around the Rhine bridge in Arnhem in July 1945. The founder donated the hunting horn to the Airborne Museum in Oosterbeek in 1997. The horn was stolen in a burglary in August of 1998. Luckily the "owner" got remorse and returned the horn to the museum in 2001.

After the war, Frost continued his military career. He held positions such as staff officer at the Gurkha Division and was in command of the 44th Parachute Brigade in London. Later he became commander of the British troops in Malta and Libya, and again later he led the Maltese army. In 1968 he was honourably discharged from the army with the rank of Major-General. During his career, Frost received many military honours.

He regularly visited the commemorations of the Battle of Arnhem, often taking the role of Leader of the Pilgrimage. In 1976 he was consulted as advisor, when the Battle of Arnhem was made into the film A Bridge Too Far. Shortly after, he received the news that the bridge at Arnhem would be called after him. This was too much honour for him, but at the insistence of his former army comrades, he finally agreed. On 16 September 1978, the road bridge over the river Rhine at Arnhem was renamed the John Frost bridge.

Frost wrote several books. In 1980 his first book was published, titled ‘A Drop Too Many’. This first part of his biography mainly dealt with his life during the Second World War and the operations he was involved in. A couple of years later in 1988, his second book was published, titled ‘2 PARA Falklands: The Battalion At War’. This book was less positively received, because Frost openly criticized army command. In his last years of life, he worked on his third book, the second part of his autobiography ‘Nearly There’, which was published in 1991. Frost died from heart disease on 21 May 1993 at the age of 80. He lies buried at the cemetery of the village Milland in West Sussex in the South of England.

Definitielijst

- Brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

Images

The hunting horn from John Frost is nowadays to see in the Airborne Museum at Oosterbeek. Source: Strijdbewijs.

The hunting horn from John Frost is nowadays to see in the Airborne Museum at Oosterbeek. Source: Strijdbewijs. John Frost (1978). Source: Strijdbewijs.

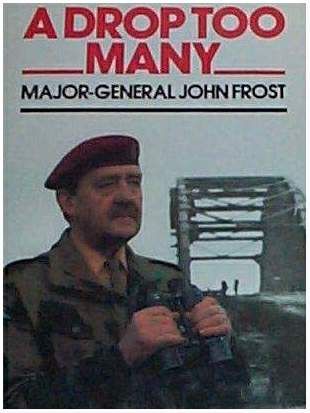

John Frost (1978). Source: Strijdbewijs. The cover from a book written by John Frost (1980). Source: Strijdbewijs.

The cover from a book written by John Frost (1980). Source: Strijdbewijs.Information

- Translated by:

- STIWOT translator

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

- 03-'42: I Was There! - 'Inside Ten Minutes the Beach Was in Our Hands'

- 02-'45: I Was There! - British Fought Like Tigers at the Ardennes Tip

- 04-'45: How the Tide of Battle Swept into Germany

- 05-'45: In the Wake of the Victors

The War Illustrated

Related sights

Sources

- CLARK, L., De Slag om Arnhem, Deltas, 2004.

- MIDDLEBROOK, M., Arnhem, ooggetuigenverslagen van de slag om Arnhem, Kosmos Uitgevers B.V., Utrecht, 2010.

- RYAN, C, Een brug te ver, Unieboek BV, Houten, 1974.

- URQUHART, R. E., Generaal van Arnhem, Boekerij, 2012.

- ZWARTS, M., Ministory 78, SS-Panzer-Aufklärungs-Abteilung 9 en de Arnhemse verkeersbrug’, Nieuwsbrief Vereniging Vrienden van het Airborne Museum nr 90, 2003.

- www.independent.co.u

- www.ww2awards.com

- www.pegasusarchive.org

- nl.wikipedia.org

- en.wikipedia.org

- www.strijdbewijs.nl

With thanks to Hans Molier, whose earlier on this website published article was a useful source for writing this article, and to Jeroen Niels for his advice.