Childhood

Baldur Benedict von Schirach was born May 9th, 1907 in Berlin. His father was Karl von Schirach and his mother Emma Middleton Lynah Tillou, an American. Baldur had two sisters, Viktoria and Rosalind and an elder brother, Karl Benedict who had committed suicide in 1919, 19 years of age. As the son of a Prussian theatremanger, Baldur grew up in an aristocratic environment. Much attention was paid to music, theatre and literature. He showed his talents as a poet at an early age. Because of the American heritage of the Von Schirach family, English was the first language Baldur learned to speak. Only from his fifth year onwards he mastered the German language a little.

At the age of 10, Baldur joined a Wehrjugendgruppe, a youth association where children were given military training. From his late teens onwards he read various anti-Semitic works such as "The international Jew" by Henry Ford and various works by Houston C. Chamberlain and Adolf Bartels. These publicaions probably formed the foundation of his anti-Semitic thinking because he stated later he had never gotten in touch with Jews in a negative way. Soon Von Schirach developed an antipathy for Christianity and his own aristocratic descent. The first is probably wholly attributable to his blind faith in Nazi ideology, which advocated secularism: Nazism would replace Christianity as some sort of would-be religion. He managed to strengthen this attitude later in his first book. "When Adolf Hitler’s book Mein Kampf was published," he wrote, "it became our Bible that we knew almost entirely by heart and with which we could give the right answer to those doubting and criticising the regime." He added that "no soundly thinking man can give me a reason for the necessity of the existence of Catholic youth organisations." His dislike of aristocratic circles was a result of his nationalism. Above all, Von Schirach wanted uniformity among the German population. Later he managed to raise this to its highest level within the education of the Hitler Youth (Hitler Jugend or HJ): "It is our duty to make the German youth secondary to our national heritage."

In 1925, at the age of 18, Baldur von Schirach became a member of the N.S.D.A.P. In the same year, he met Adolf Hitler (Bio Hitler). Von Schirach was enthousiastic about him immediately: "I went to study in Munich because he worked there and I became one of his most faithful followers," he wrote. "From that moment on I was a dedicated anti-Semite." Just like many others, Von Schirach was convinced that Hitler would become the "saviour of Germany." Von Schirach’s left wing nationalistic preference was mainly based on his dislike of his own background. In his view, the class system should be abolished if one wanted to achieve unity among the population. In order to put his ideas into practise, Von Schirach advocated drastic measures: Germany’s misfortune had to be reverted as soon as possible because the Treaty of Versailles was a humiliating stain on his existence as well.

Von Schirach’s anti-Semitic prejudices, which had matured early, played an important role in his political preference. As mentioned earlier, he devoted himself at an early age to anti-Semitic publications and subsequently developed an unfounded hatred towards Jewry. Undoubtedly, his slavish devotion for Hitler and Nazism can be attributed to Hitler’s charisma and also to the influence race ideologist Alfred Rosenberg (Bio Rosenberg), as well as the editor-in-chief of the anti-Semitic paper Julius Streicher exerted on him and to a lesser extent, to the promises of the Nazi party. In addition, the quest for unity among the German population played a big role as well for him and the other Nazis. As mentioned earlier, a fervent nationalist like Von Schirach had these ideals high on his list.

Baldur von Schirach soon made a reputation for himself in the Nazi party. As the ambitious young man he was, he put up various ideas about nazification of German youth and the universities which were positively received in general, in particular by Hitler. Through this, Von Schirach quickly gained popularity, enabling him too rise quickly through the hierarchy of the party. He was asked to draft a number of concrete plans based on his outspoken ideas. These were also received positively and enabled him to meet Hitler personally at the Berghof. A number of talks concerning the nazification of youth and higher education nourished the personal relationship between Hitler and Von Schirach. Von Schirach kept being impressed by Hitler: "This prophet, sent by God, is our saviour and the only man who can drag Germany out of her misery, " as he voiced frequently as a young man.

More than a year later, in 1926, he took his diploma of the gymnasium and subsequently, on Hitler’s advice, he went to study Germanic folklore, history of arts and English literature at Munich University. He did not complete his university studies though, two years later he decided to drop out and devote himself entirely to his Nazi career.

Definitielijst

- Berghof

- A villa hidden deep in the Alps built at the top of the Obersalzberg near Berchtesgaden. This villa was property of Hitler and centre of the ”Alpenfestung”. The villa has an enormous complex of tunnels with a length of nearly 11 km. From the Berghof the Third Reich was ruled by Hitler and his close companions. Eva Braun, Hitler’s companion, spent a lot of time there.

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Mein Kampf

- “My Struggle”. Book written by Adolf Hitler, outlining the principles of National Socialism.

- nationalism

- The pursuit of a people to become politically independence or securing such independence.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Nazism

- Abbreviation of national socialism.

Images

Early Nazi career

In 1928, he moved to Munich to accept his appointment as Führer des Nationalsozialischtischen Deutschen Stundentenbundes (N.S.D.S.B.) or leader of the Nationalsocialist Students Union on July 20th. In this capacity he mobilised the academic youth for nationalsocialism. His outstanding organisatorial capacities enabled him to be invited to the Berghof more frequently to enhance his personal relationship with Hitler. He already managed to flatter Hitler with his first poems, glorifying him to a superhuman level. Meanwhile his organisational capacities did not remain unnoticed. Von Schirach presented himself as a hard worker with a capability to find solutions for the most difficult logistical problems. The fact that he had renounced his aristocratic origins and had developed anti-Semitic ideas at a young age enabled him to be considered by many high ranking Nazis a real trusted representative. In addition, his love for Nazism, the German culture and his adoration of his great hero Adolf Hitler contributed to his nationalistic feelings: something Hitler looked for in his subordinates. His academic background gave the impression he was an intelligent man with a solution always at hand.

On December 19th, 1928, Von Schirach and some other academics founded the Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur (Union for German culture). With this, he attempted to spread the work of Goethe, to name just one, and other truly German literature among the German population. There can be hardly any doubt that Von Schirach wanted to promote nationalism by spreading German history and literature among the German population. In 1931 he was given the position of Reichsjugendleiter der N.S.D.A.P. (state youth leader of the N.S.D.A.P.) and was put in charge of the HitlerJugend. He received authority over this youth organisation, numbering about 100.000 members in as early as 1932 and he could begin to realise his ideas about nazification of German youth.

Von Schirach married 19 year old Henriette Hoffman on March 31st, 1932, the daughter of Hitler’s personal photographer Heinrich Hoffman. The ties Von Schirach’s father in law had with Hitler soon made Baldur as well as his recently married wife regular guests at the Berghof, Hitler’s residence in Berchtesgaden where he could be found frequently during his period in power. Von Schirach managed to find a place in Hitler’s inner circle of friends.

Definitielijst

- Berghof

- A villa hidden deep in the Alps built at the top of the Obersalzberg near Berchtesgaden. This villa was property of Hitler and centre of the ”Alpenfestung”. The villa has an enormous complex of tunnels with a length of nearly 11 km. From the Berghof the Third Reich was ruled by Hitler and his close companions. Eva Braun, Hitler’s companion, spent a lot of time there.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- nationalism

- The pursuit of a people to become politically independence or securing such independence.

- Nazism

- Abbreviation of national socialism.

Images

Youth leader of the Third Empire

After the seizure of power in Germany by the Nazis, Hitler offered the position of Jugendführer des Deutschen Reiches (Youth leader of the German Empire) to Von Schirach, along with the rank of SA Gruppenführer. Von Schirach held this post from June 17th, 1933 onwards. As freshly appointed leader of German youth, he immediately set about nazifying all youth organisations. All German youth organisation were to be nazified and just like his HJ, function entirely under the banner of nationalistic ideals.

Von Schirach had the offices of the Reichsausschuβ Deutscher Jugendverbände (State committee for German youth organisations) occupied. The head of this organisation, General Vogt was summarily kicked out. Subsequently, Von Schirach engaged one of the most famous German naval heroes, Admiral Von Thotha, Chief of Staff of the Hochseeflotte (High seas fleet) in World War One and now president of the youth associations. Even the revered war hero could not resist Von Schirach. The just 26 year old youth leader of the Third Empire had managed to sidetrack all dedicated youth organisations, except the Catholic. These remained temporarily out of reach as the Nazi government had signed a concordat with Pope Pius XI on July 20th, 1933. This concordat stipulated an appeasing attitude between Nazism and the Catholic faith.

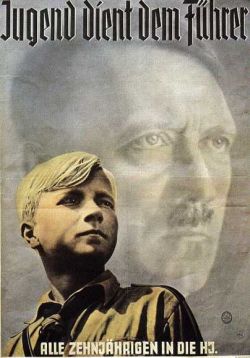

Meanwhile the HJ presented itself as a paramilitary youth organisation with Hitler and the Nazi ideology as its central themes. This youthful opposite of the SA or Sturmabteilung was to provide soldiers for the German Empire in the future. In addition, its members could also go on to Nazi educational institutes or military academies to prepare themselves for a function as Nazi leader. Members of the HJ were offerd more than just military training though; group trips and scouting activities were also quite common. An additional goal was to maintain and stimulate national unity. Clearly obvious were the roots of the HJ: the concept of Spartan upbringing. German youth should be inflexible, tough and strong or in Adolf Hitler’s words: "Zäh wie Leder, schnell wie Windhünde und stark wie Kruppstahl" (As tough as leather, as fast as greyhounds and as strong as Krupp steel).

The choice of a man as Von Schirach to head an organisation which emphasised energetic activity, discipline and special emphasis on the ideal of physical perfection, is ironic and remarkable however. Among the regular visitors at the Berghof, he was known from the beginning as "a slimy character lacking the necessay qualities for our ideal fatherland." To many he was the exact opposite of a true Nazi leader, characterised by ruthlessness, determination, toughness and an unconditional sense of honour. Hitler however recognised in his tender age the ideal leader type for his organisational talent and his unequalled devotion to him as Führer and to Nationalsocialism.

Even as Jugendführer des Deutschen Reiches Von Schirach engaged in poetry. Especially within the HJ, his poems gained increasing popularity. In the years following his appointment as leader of the HJ, he wrote various romantic poems about Hitler, raising him to some kind of Messiah:

"Führer, my Führer, given by God,

You saved Germany in its hours of highest need,

I thank you for my daily bread,

Stay with me forever, do not ever leave me,

Führer, my Führer, my faith, my light.

Hail my Führer!"

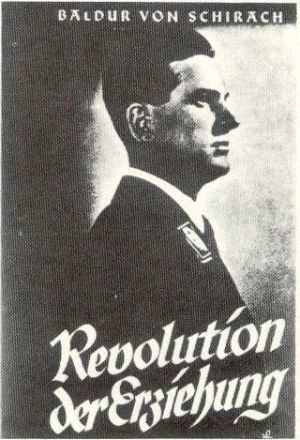

His idolatry of Hitler also showed in his first book from 1932: "Hitler wie Ihn keiner kennt." (Hitler as nobody knows him). In 1934 he wrote "Die HitlerJugend" and in 1938 he followed up with "Die Revolution der Erziehung" (the revolution of education). Here also he continued to portray Hitler as a benefactor sent by God. According to Von Schirach, these ideas had to be stamped on the minds of the HJ. The boys in the HJ for instance were obliged to recite the poem mentioned above prior to each meal. Also well known was the so called "Bekenntniss zum Führer" (plea to the Führer), each member of the HJ had to know it by heart and which reads as follows:

"We heard your voice ring out so often, we listened in silence and folded our hands because each word penetrated our souls. We all know: once the time will come that will free us from need and arbitrariness. What is a year in eternity. What is a law prohibiting this. The pure faith, given to us by you, surely penetrates our young lives. My Führer, you alone are the Way and the Goal!"

Von Schirach was appointed state secretary for youth on December 1st, 1936. That same day, a law was passed making membership of the HJ mandatory for all youth within the Greater German Empire. A big step for a man like Baldur von Schirach: now he could finally mould the German youth after his own image. He immediately disbanded all other youth organisations (at that time numbering about 6 million children), such as the Wandervögel and the Bündische Jugend. At that time, Von Schirach had already seen to it that the average intellectual level within the HJ had decreased considerably. Intellectual knowledge was limited to slogans, poems and songs. "Wir marchieren für Hitler in Nacht und Not hinter der Fahne der Jugend für Freiheit und Brot" (We march for Hitler in night and need, behind the flag of youth for freedom and bread). All these lyrics were by Von Schirach.

The philosophy concerning German youth in the Third Empire was that they had to be made ready as full fledged Nazis, indoctrinating the youth with military values and the Nazi ideology. Possible resistance had to be prevented: the youth was to brainwashed to develop a blind faith in the entire Nazi system. Uniformity and equality had to be prevalent among the German population: for instance they had to hold hands while singing songs around the campfire. The youth was continuously made aware of how important they were for future Germany: youthfullness was raised to almost the highest asset that made young people like Von Schirach extremely useful as leaders of this organisation. The youthfullness of their leaders was to be an example for the members of the HJ to make it clear for them continuously what exactly was the value of youthfullness.

Despite numerous passionate attempts, Von Schirach never succeeded in becoming a real representative of what Hitler described as the ideal type. His ambiguous conduct triggered much controversy within the party and the lower ranks of the HJ. Although he had not finished his university studies he did attempt to pretend being a sophisticated academic on the one hand and on the other hand he tried to emulate the spirited style and the tough conduct of the HJ. Although Von Schirach had already attempted to hide his noble origins from a young age onwards, he proved time and again he had failed in this. Von Schirach was neither harsh, nor tough, nor sharp, but more like a weak and spoiled boy who only felt safe in his party uniform. This image was even strengthened by his wife, Henriette Hoffman who described him as "a weak figure for whom the pose was more important than the goal". These characteristics gave rise to persistent rumors that indicated latent homosexual leanings. In the course of time, these were further nourished by other rumors, like his seemingly woman like traits, his slimy poems and speeches, in particular those aimed at Hitler, his feminine looking bedroom and his forced manly conduct. Moreover, many high ranking Nazis held the view that Von Schirach did not owe his position to his qualities and his capabilities but to his slimy behaviour towards Hitler.

In order to show his critics such as Hitler’s private secretary Martin Bormann (Bio Bormann) his courage, he reported for service in the Wehrmacht in December 1939. After training in Berlin-Döberitz, he was posted to the famous Gross Deutschland division with which he became involved in the invasion of France in May 1940. His ‘heroic’ conduct lasted only a few weeks, enabling him to enjoy French life for a while. Shortly after he was promoted to Oberleutnant. After this performance, he was awarded the EK 2 (Eisernes Kreuz 2te Klasse or Iron Cross 2nd Class) and the Infanterie Sturmabzeichen in Bronze (Infantry Badge in Bronze).

Definitielijst

- Berghof

- A villa hidden deep in the Alps built at the top of the Obersalzberg near Berchtesgaden. This villa was property of Hitler and centre of the ”Alpenfestung”. The villa has an enormous complex of tunnels with a length of nearly 11 km. From the Berghof the Third Reich was ruled by Hitler and his close companions. Eva Braun, Hitler’s companion, spent a lot of time there.

- Eisernes Kreuz

- Iron Cross. German military decoration.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Iron Cross

- English translation of the German decoration Eisernes Kreuz.

- Krupp

- German family of steel and weapon’s manufacturers.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Nazism

- Abbreviation of national socialism.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Revolution

- Usually sudden and violent reversal of existing (political) the political set-up and situations.

- Sturmabteilung

- Storm detachment. Semi-military section of the NSDAP. Founded in 1922 to secure meetings and leaders of the NSDAP. Their increasing power was stopped during “The night of the long knives”, 29 and 30 June 1934.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Baldur von Schirach giving the Hitler salute to marching HitlerJugend in Nuremberg, 1933. The man in the light uniform in front of the car is Julius Streicher, editor of Der Stürmer". Source: USHMM.

Baldur von Schirach giving the Hitler salute to marching HitlerJugend in Nuremberg, 1933. The man in the light uniform in front of the car is Julius Streicher, editor of Der Stürmer". Source: USHMM. Von Schirach amomg members of his HiterJugend. Source: http://www.law.umkc.edu.

Von Schirach amomg members of his HiterJugend. Source: http://www.law.umkc.edu.Gauleiter of Vienna

From September 1940 onwards, Baldur von Schirach directed the evacuation of some 2.5 million children from cities that were threatened by Allied bombing attacks. This so called Kinderlandverschickung came into being after various urban areas had been subjected to Allied bombings and evacuation was necessary now to protect the children. These children were housed in some 9.000 camps, scattered all over the German Empire. Not only was their schooling continued here, all other activities of the HJ continued also and all necessary measures were taken to continuously imbue the children with Nationalsocialism. This Kinderlandverschickung was set up by the HJ and this explains Von Schirach’s prominent role in this evacuation. Of course, numerous logistical problems popped up and in order to let this massive evacuation proceed in a relatively smooth manner, a man like Von Schirach was indispensable.

On August 7th, 1940, Von Schirach lost his position as Jugendführer des Deutschen Reiches and leader of the HJ to Artur Axmann (Bio Axmann). Subsequently he was named Gauleiter (party leader of a region) and Reichsstatthalter (State stadtholder) of Vienna. This post provided him with total responsibility and authority over Vienna. In the 4.5 years he held this position, he was co-responsible for the deportation of the remaining Jews in his Gau to Poland and the Soviet Union were the majority of them was murdered in the extermination camps or by the Einsatzgruppen (Einsatzgruppen Art.). It concerned some 60.000 members out of the original Jewish population of some 190.000 of which the majority had emigrated under pressure from the Zentralstelle für Jüdische Auswanderung (Central Agency for Jewish emigration), headed by Adolf Eichmann (Bio Eichmann) following the annexation of Austria. Although he left the actual deportation to Heinrich Himmler’s SS (Bio Himmler), he was actively involved in the process. On October 2nd, 1940, he discussed with Hans Frank (Bio Frank) the question whether he could deport the the remaining Jews in Vienna to the GeneralGouvernement in Poland, which was ruled by Frank. On December 3rd, he also received an order from Hitler to deport all remaining Jews in Vienna. In a speech, deliverd on September 15th, 1942, he indicated he considered the deportation of the Jews a contribution to European culture.

As the military pressure by the Allies began to take on increasingly serious forms and protecting the cities in the Third Reich was high on the list of priorities, Von Schirach was also appointed Reichsverteidigungskommissar für den Gau Wien (State comissioner for defence of Vienna) in July 1942. In the previous year, he had been promoted to SA Obergruppenführer enabling him to maintain more authority in the city of Vienna.

And yet, the former leader of the HJ could not depart from his origins. The would-be academic took the position of Präsident der Großdeutschen Bibliophilen Gesellschaft (President of the Great German Library Association) on September 28th, 1941. This association of German intellectuals was restricted to dedicated Nazis and was engaged in classifying pro- and anti-Nazi publications. On June 29th, 1942 Von Schirach was named Senator der Deutschen Akademie (Senator of German Academy). This position enabled him once more to mobilise the academic youth for Nationalsocialism and at the same time flood the academic system with the Nazi ideals.

Definitielijst

- Gau

- “Shire”. District in the Third Reich established by the NSDAP.

- Gauleiter

- Leader and representative of the NSDAP of a Gau.

- GeneralGouvernement

- That part of Polish territory occupied by the Germans in 1939. It was an autonomous part of Greater Germany. In August 1941 Eastern Galicia was added to the Generalgouvernement. It was governed solely by Germans under direction of Generalgouverneur Hans Frank. It was to become a full German province inhabited only by German colonists.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Images

Arthur Axmann, Von Schirach’s successor as Jugendführer des Deutschen Reiches and leader of the HitlerJugend. Source: DHM.

Arthur Axmann, Von Schirach’s successor as Jugendführer des Deutschen Reiches and leader of the HitlerJugend. Source: DHM. Propaganda poster for the Kinderlandverschickung. Source: http://www.calvin.edu.

Propaganda poster for the Kinderlandverschickung. Source: http://www.calvin.edu.Fallen into disgrace

From his first years as Gauleiter and Reichsstatthalter of Vienna onwards, the split between Von Schirach and Hitler widened. Earlier on, Von Schirach had criticised Hitler’s war of agression in the west more than once. Meanwhile Hitler’s distrust of the Gauleiter had grown rather strong and was based on Von Schirach’s American descent in combination with his cultural policy. Despite his devotion to Nazism, Von Schirach attempted in every way possible not to denounce his cultural attraction to the west. Early 1943 this came into the open when Von Schirach organised an exhibition containing so called degenerated art that did not match the attitude of the Blut und Boden (blood and soil) theory. This theory stipulated that art had to be purely Germanic and there could be no question of forein influences. According to Nazi standards, western art was too modern, contained too much foreign influence and was too chaotic. Western art would affect the image of Germany in a negative way because it did not match the Nazi ideals of order and discipline. Hitler felt attacked by Von Schirach’s exhibition and he blamed the Gauleiter for: "leading the cultural opposition against him in Germany." All this formed the fertile soil for the later split between the two men.

This split between the Von Schirach couple and Hitler was caused In large measure however to the behaviour of Von Schirach’s wife Henriette. In 1943, she was invited by friends, who worked with the German forces of occupation in the Netherlands, to come and visit them. She decided to visit Amsterdam first where she witnessed a razzia during which hundreds of Jewish women were arrested. She was shocked and asked her friends what this action meant. It was explained to her that it entailed the deportation of Jewish women to Poland and they asked her if she had ever heard about it. She made herself believe that Hitler had nothing to do with this action and was not resposible for it. She was advised to speak immediately to the Führer in person.

Henriette von Schirach broke off her visit to the Netherlands prematurely in order to contact the Berghof immediately to make an appointment with Hitler. The Berghof however was not suitable for talks and discussions concerning political issues. Matters like the policy against the Jews, their persecution and the concentration and extermination camps were way off limits. Indignantly Henriette asked Hitler whether he knew of the razzias; she was firmly convinced Hitler had nothing to do with it. She described what she had witnessed a few days before and asked Hitler why these women were being arrested. In reaction to her question, Hitler burst into a tirade.

Henriette’s description of the rest of the evening, when the roots of the split between the Von Schirach’s and their marked saviour became all too obvious, is impressive. "He stood up very cautiously," so she tells, "and an icy silence fell over the grand hall. Only the crackling of the burning chunks of wood in the fireplace could be heard. I stood too. At that moment he yelled at me: ‘You are sentimental Frau von Schirach. You must learn to hate. What are those Jewesses in the Netherlands to you?’ Meanwhile he had grabbed my wrists, just like before and held them with both hands so I could better concentrate on him. Suddenly he let go of me. ‘Don’t you understand then? Each day, tens of thousands of my best, my most valuable soldiers lose their lives. Those others do not die, they live in concentration camps. The inferior remain alive and what will Europe look like in a hundred years? Or in a thousand years? I am responsible to my people only and to no one else."

Later that year at the Berghof, on June 24th, 1943, Von Schirach advocated better treatment of the Jews and East-Europeans and criticised the method of deportation. It is remarkable though that he had not criticised he Jewish policy for years and had indicated more than once that the "Jewish policy is necessary for the preservation of Germany." Consequently he fell from Hitler’s grace entirely but he managed to hold on to his position of Gauleiter and Reichsstatthalter.

Definitielijst

- Berghof

- A villa hidden deep in the Alps built at the top of the Obersalzberg near Berchtesgaden. This villa was property of Hitler and centre of the ”Alpenfestung”. The villa has an enormous complex of tunnels with a length of nearly 11 km. From the Berghof the Third Reich was ruled by Hitler and his close companions. Eva Braun, Hitler’s companion, spent a lot of time there.

- Blut und Boden

- “Blood and soil”. Term used by Adolf Hitler to describe the idea that people from German descent (German blood) had the right to live on German soil. Although not necessarily negative, the Nazis turned this idea into an ideology which they actually put into practice following the example of Walther Darré, head of the Rasse-und Siedlungs Hauptamt (RuSHA) (”Race-and Settlement bureau”).The Nazis also used this term to justify the extermination of the Jewish people.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Gauleiter

- Leader and representative of the NSDAP of a Gau.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Nazism

- Abbreviation of national socialism.

- razzia

- Organised round-up of a group of people. This could be Jews but also persons in hiding or other groups.

Arrest and trial

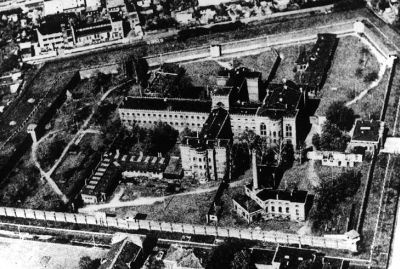

In the last days of the Third Reich, Von Schirach was mainly occupied with his job as State Commissioner for the defence of Vienna. In February and March, 80.000 tons of Allied bombs were dropped over Vienna. The result was 30.000 civilians killed, 12.000 buildings destroyed and 270.000 homeless. For months on end, the inhabitants had to make do without electricity, water or gas. Von Schirach made relentless attempts at evacuation and shelter for the homeless but all to no avail. The German Empire, which had almost totally collapsed, simply lacked the means to help its citizens any longer and moreover, Von Schirach was expressly forbidden by Hitler to look after the inhabitants. In Hitler’s opinion, the prevalent military situation took priority over the needs of the citizens of the Reich. During the offensive on Vienna between April 2nd and 13th , 1945 the Soviets bombarded the city mercilessly. Just a few days later, all of Austria had been conquered.

Following the fall of the Third Reich, Von Schirach initially went into hiding and attempted to fake his own death with fabricated evidence. Ultimately he repented when he acknowledged he had to atone for his actions. He had seen the horrors of the Holocaust. He knew for instance about the mass executions by the Einsatzgruppen in the Soviet Union as he had received various reports on this.

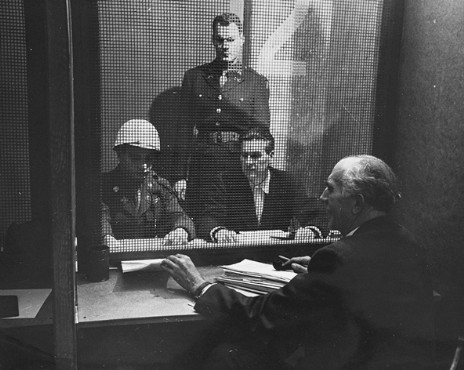

Shortly after the fall of the Third Reich, Von Schirach surrendered to the Allies and subsequently stood trial before the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. This Tribunal had been established in order to prosecute the top Nazis and war criminals. He was charged with conspiracy to wage aggressive warfare or crimes against peace and crimes againsrt humanity. The Allies knew about the deportation of the Viennese Jews during Von Schirach’s tenure in Vienna. In addition, Von Schirach had been responsible for poisoning German youth, according to the Tribunal. As concerns his conduct as Gauleiter, his first written reaction read: ‘The whole disaster had to be blamed on race policy’. He appeared willing before the judges and according to the prison psychologist he was entirely at peace with his death. During the hearings he was very nervous though.

In his cell, he could not stop writing poems either. He wrote "To death", among others, in which he voiced his reconcilliation with a possible death sentence. Although he probably would be hanged as a war criminal, Von Schirach did not renounce his background. The aristocratic environment in which he was raised and had remained in for the better part of his life, always clung to him. This way he maintained his pompous attitude towards the Tribunal and its associates. At their first meeting, he told his counsel: "As long as I have my head, I will hold it straight."

In accordance with the way in which he had let himself be taken prisoner, Von Schirach displayed an extremely repentful attitute before the Tribunal. The fact that his entire family had been arrested as well and he regularly indicated he would like to be with them again, probably played a role in this. His weakness however was displayed in full during the trial. In the hearings, he disassociated himself from Albert Speer who initially showed an extremely repentful attitude, just like he did himself. The former leader of the HJ came under such an influence from Hermann Göring that he included the opinion of the party in his statements instead of his own opinion and history. In the presence of Göring, Von Schirach’s answers remained vague and unclear and above all he did not dare to go onto the defence. In Nuremberg the former Gauleiter and Reichsstatthalter of Vienna voiced more than once that he had committed himself not only to Nationalsocialism but also to German literature and music. Before the Tribunal he even attempted to drag in Goethe when he pleaded for more understanding of the foundations of Nationalsocialism. He was interrupted regularly and was exhorted to stick to the case.

His original plan to compile a charge about Hitler’s betrayal came to nought and according to the prison psychologist, all attempts to make him repent were dead from the beginning. The main argument was that he would suffer too much loss of face, confirming his earlier statement "As long as I have my head, I will hold it straight." Although Göring had called Von Schirach a young weakling once, the former youthleader of the Third Reich maintained tenaciously that it would be foolish to sentence his hero Hermann Göring, mainly because he was so popular. In his opinion his (Von Schirach’s) enemy Joachim von Ribbentrop took more blame for the war and it had been Von Ribbentrop who had really influenced Hitler and not Göring.

He portrayed the HitlerJugend as an innocent scouting club, where there was no question of military training and Nazi ideology only played a minor role. Concerning the HJ, he also tried to disassociate himslef completely from the racial policy and in particular the Jewish policy. He remarked for instance that he and German youth had hoped to find a peaceful solution to the Jewish problem. He denounced involvement of the leadership of the HJ in the Nuremberg Laws on Races of 1935 and stated that the German youth had not made itself guilty of violence during the Kristallnacht in November 1938. Von Schirach did admit however that in his opinion the Jews were a "true cultural dishonor" , that they were guilty of poisoning German youth and partly responsible for the decadence of the Third Reich.

In the course of the proceedings, the American prosecutor Mr. Dodd forced Von Schirach to admit he, in October 1940, had asked Hans Frank, the Governor of occupied Poland to deport 50.000 Viennese Jews to that country. Frank had protested against this proposal for logistic reasons because there might be not enough space in Poland. Ultimately, the Gauleiter of Vienna managed to put his foot down and Hitler gave order to deport the remaining Viennese Jews. Essential in the trial against Von Schirach in connection with his role in the deportation of the Viennese Jews was evidence that at the time of these deportations, he had received various reports about the Einsatzgruppen in the Soviet Union. These reports not only described how effective these mass executions were but the methods as well with which thousands of "undesirables" were liquidated. Nevertheless, Von Schirach allowed the deportation trains to roll on; in all probability knowing full well what kind of fate was awaiting his Jews in Poland. As to his anti-Semite attitude he declared: "I had no reason to be an anti-Semite but my well founded attitude at that time left little room for doubt."

Before the Tribunal, he argued for instance he had known nothing of the existence of extermination camps and he also showed evidence of his protests to Martin Bormann against the inhuman treatment of the Jews. On August 31st , 1946 he delivered his final statement before the Tribunal: Final Von Schirach.

On October 1st, 1946, the Tribunal sentenced him to 20 years imprisonment for crimes against humanity based on the deportation of Jews from Vienna although: "this policy did not originate from him but he was actively involved." He probably owed his relatively short prison sentence to his initial repentence and the critcism of Hitler he voiced along with Albert Speer. (see Verdict Von Schirach).

Definitielijst

- crimes against humanity

- Term that was introduced during the Nuremburg Trials. Crimes against humanity are inhuman treatment against civilian population and persecution on the basis of race or political or religious beliefs.

- Gauleiter

- Leader and representative of the NSDAP of a Gau.

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Nuremberg Laws

- Laws promulgated by Hitler on the party convention on 15 September 1935. These laws alter alia included regulations about marriage and intercourse between Jews and non-Jews. Jews were deprived of German citizenship. Also known as the racial laws.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Images

Final years

On July 20th, 1950, his wife Henriette divorced him during his stay in Spandau prison in Berlin. He was released on September 30th, 1966, after which he moved to southern Germany in all tranquility. There he wrote his memoirs: "Ich glaubte an Hitler" (I believed in Hitler), published in 1967. In them he argued again to have known nothing of the mass murders at the time of the deportations of the Viennese Jews. In essence, the book contains the same as his testimony in Nuremberg. Again he took full responsibility for having educated German youth in connection with a faulty programme of indoctrination. He also indicated that one charge bothered him most: according to the Tribunal he would have urged the deportation of the Viennese Jews. The Tribunal also argued that he undoubtedly had known very well what he was doing. Von Schirach continued to deny it; he based his statement on the argument that he had heard of the extermination camps only after the deportations.

In the folowing years, the former youthleader lived in isolation in a mountaineous area in southern Germany. He passed away in his sleep on August 8th, 1974 in a small hotel in Kröv on the river Moselle, almost entirely isolated and as good as blind as result of an eye disease.

Definitielijst

- indoctrination

- The education or brainwashing of people, sometimes by force, to accept a certain opinion or political doctrine. This doctrine is to be followed henceforth without question.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

Images

Information

- Article by:

- Bob Erinkveld

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related books

Sources

- CAPELLE, H. VAN & BOVENKAMP, P. VAN DE, Hitlers handlangers, Verba, Soest, 2004.

- LEWIS, B., De geschiedenis van de Hitlerjugend, Zuidnederlandse Uitgeverij, Aartselaar (België), 2003.

- WISTRICH, R.S., Who's who in Nazi Germany, Routledge, Londen, 2002.

- Jewish Virtual Library (2)

- Baldur von Schirach: Leider van de Hitler-Jugend

- Wikipedia: Baldur von Schirach

- Wikipedia: Vienna Offensive

- Lebendiges virtuelles Museum Online

- Spartacus Educational

- Anovi: Seconde Guerre Mondiale

- Maaslandweb

- WDR: Vor 30 Jahren: Baldur von Schirach stirbt

- Shoa.de

- Bookrags: Baldur von Schirach summary