Introduction

Even today, the Englandspiel is still considered one of the great mysteries of World War Two in the Netherlands. Between March 1942 and May 1943, dozens of agents, dropped by the British, fell in German hands right after landing on Dutch territory. They were deployed in a plan (Spiel) set up by the Germans giving the impression they were still operating in freedom while the British continued sending secret agents and material to the Netherlands. What was going on? Were the British secret services victims of a German deception or were the Germans being deceived themselves? What were the causes of the British incompetence? How could it take so long before the British found out what was really happening?

Definitielijst

- Englandspiel

- “England game”. The game, ironic as it may sound, of espionage and counter espionage between the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the Nazis. This “game” resulted in the death of approximately 54 allied spies.

Images

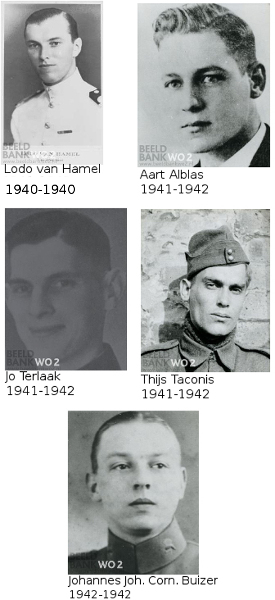

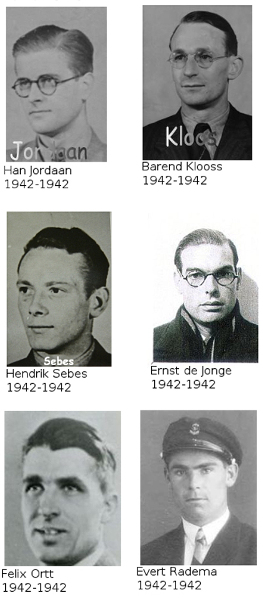

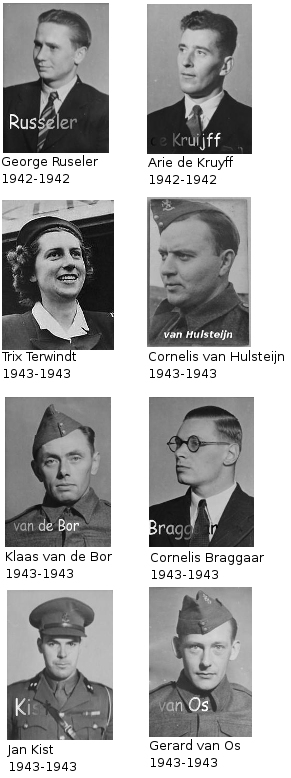

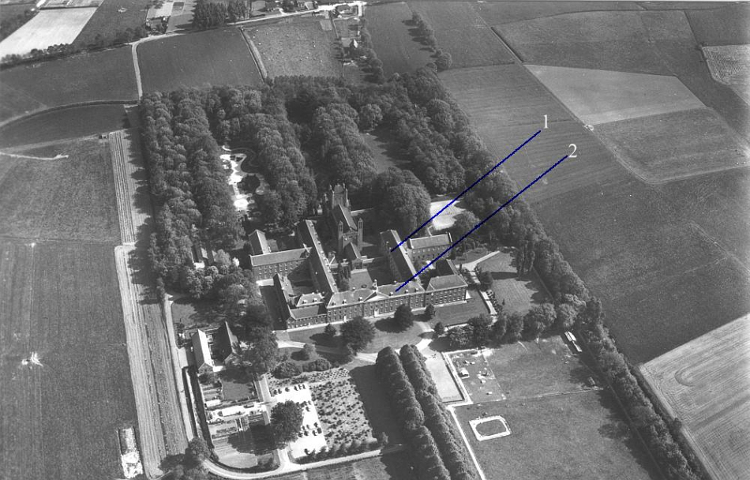

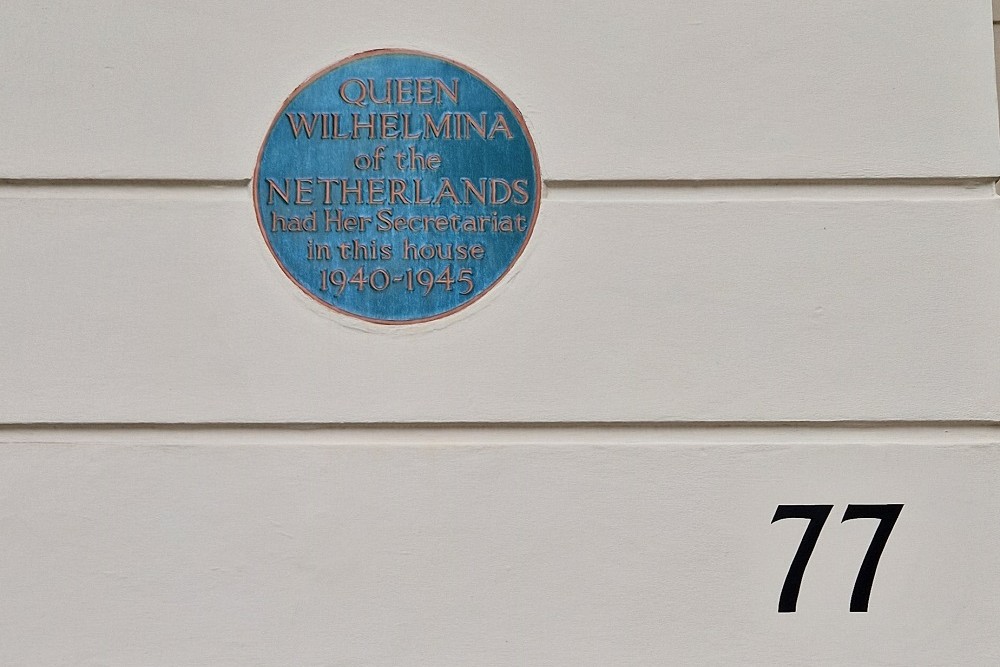

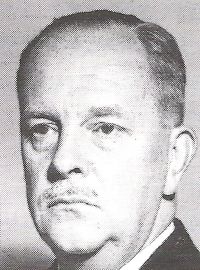

Between March 1942 and May 1943 dozens of agents have been dropped over Dutch territory by the British. Source: jelterep.nl.

Between March 1942 and May 1943 dozens of agents have been dropped over Dutch territory by the British. Source: jelterep.nl.How it began

Previous history

Soon after the Dutch government had gone into exile in England following the German invasion in May 1940, she tried to make contact with occupied Holland. The newly established Centrale Inlichtingendienst (C.I.D., Central Intelligence Service) headed by François van ‘t Sant attempted to set up a web of agents in the Netherlands in cooperation with the British secret service MI6. In this connection, the first agent, Lodo van Hamel was dropped on August 27th, 1940. Initially his mission appeared successful. He managed to set up a small network and contacted England numerous times. This agent, sent by Van ‘t Sant, was arrested on October 15th, 1940 in Friesland however while he was waiting for a seaplane that was to pick him up. On June 16th, 1941, he ended before a firing squad. The Germans failed to get their hands on his transmitter and his code. Subsequently, a few more agents were sent, including Cees van Brink (November 19th, 1940) and Aart Alblas (April 5th, 1941). Van ‘t Sant wished to set up an underground ring of intelligence agents in the Netherlands, moreover because such operational networks already existed in German occupied countries such as Norway and France. Many of the agents were arrested sooner or later by the Germans. Alblas did manage to evade capture by the Sipo (Sicherheitspolizei, security police) for some time. He was arrested on July 6th, 1941.

In July 1940, a new secret service was established in Great Britain, the Special Operations Executive (S.O.E.). This agency was charged with stirring up resistance on the European mainland. The resistance had to be encouraged, trained, equipped and supplied. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (Bio Churchill) hoped to create a Fifth Column to serve the Allied cause. According to British historian Max Hastings, Churchill envisaged four goals:

Achieving military goals; creating the impression among the British population and the rest of the world that war was waged energetically and effectively; forcing Hitler to apply measures to maintain security within the Reich and causing tension, mutual accusations and hatred between the German and the populations suppressed by them."

This last item was the most important goal. Churchill was afraid the occupied population would collaborate with the Germans on a large scale. He hoped to prevent this by increasing the resistance and consequently the German counter measures.

The S.O.E. consisted of several departments, each focusing on a specific country. On December 20th, 1941 an independent Dutch Section was established within the S.O.E. and headed by Major Richard Laming. Previously, the S.O.E. had dispatched an agent to the Netherlands, Jan van Driel. He arrived by boat off the beach near Oost Voorne in the night of August 17th to 18th. He came ashore safely but lost his transmitter in the process. Consequently, he was unable to contact England and he also failed to set up a resistance group in the Netherlands. The C.I.D. was completely ignorant about Van Driel’s mission. Cooperation between the S.O.E. and the C.I.D. was bad, this was especially due to Laming who stubbornly refused to cooperate with Van ‘t Sant. He in his turn wouldn’t have anything of those fumblers of the S.O.E., probably because he frequently cooperated with and was influenced by MI6. Just like between Laming and Van ‘t Sant, there was no love lost between both services.

Initially, the S.O.E. Dutch Section operated behind the backs of the Dutch agencies, due to their bad relationship with the Dutch government and Van ‘t Sant. Agents were recruited among Dutchmen abroad. Many Dutch, who were not in the country in May 1940, for instance as they sailed aboard a merchantman or temporarily lived abroad because of their work, came to Great Britain hoping to be able to fight against the Third Reich. A number of them reported voluntarily to be dispatched to the Netherlands as secret agent. Others were approached by the S.O.E. or MI6 because these services considered them suitable for these posts. During the war, a number of Engelandvaarders (people who had escaped from the Netherlands to England by boat mostly) reported for service as secret agent.

Laming was compromised when three candidate agents, who had complained about the quality of the training and the material provided by S.O.E. were interned in a penal camp in Scotland. Consequently, Laming was replaced by Major Charles Bizard in early 1942. The bad relations between Laming and the Dutch may well have played a part in this.

The first drops

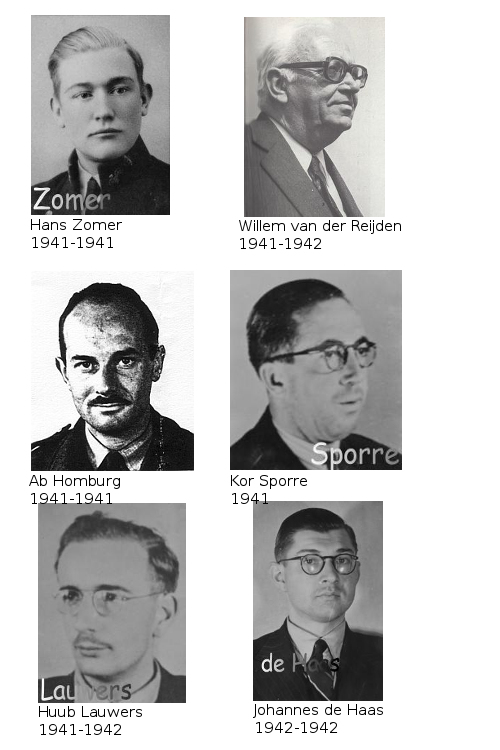

The Englandspiel started in fact on August 31st, 1941. Wireless operator Hans Zomer, who had been dropped on July 13th, 1941 with MI6 agent Wiek Schrage near Vledder in Drenthe, was arrested by officers of the Sipo that day. Zomer had made the mistake to keep a few old message, coded as well as decoded, at his radio location. That kind of mistakes was made frequently by secret agents. Assisted by code expert Ernst May and on orders by the Abwehr (German intelligence service), the Funkbeobachtung managed to decipher them. In February 1942, two more MI6 agents were arrested: Jo Terlaak (dropped on October 1st) and Willem van der Reyden (landed by boat on December 9th, 1941), who provided the Germans with information; Terlaak only did so after having been brutally tortured. Van der Reyden volunteered much information on the organization in Great Britain a well as in the Netherlands, because he assumed he had fallen in German hands as a result of betrayal. After his arrest, Van der Reyden handed over his code to the Germans, something he was allowed to do according to the instructions he had received in England. On orders of the Germans, he transmitted a message but intentionally omitted his security check as agreed beforehand. Thereupon MI6 broke contact with him. As a result of the arrests, the Germans now had the British coding system at their disposal. Using Zomer’s transmitter to set up a Funkspiel (the agent giving the impression he was still operating in freedom but in reality was supervised by the Germans) had failed before because MI6 had seen through the ruse, so Schreieder of the S.D. (Sicherheitsdienst, German secret service) decided if an opportunity presented itself again, he would leave it to the Abwehr.

On September 3rd, 1941 two new agents were dropped by S.O.E. Dutch Section over Noord-Brabant: Ab Homburg and Kor Sporre. They had no transmitters. Their only task was to make contacts and find dependable addresses for future agents. They had little success. Homburg was arrested on October 6th and sentenced to death on October 10th without a proper trial. He was transferred to the Oranje Hotel (a prison) in Scheveningen. In the morning of October 26th, Homburg managed to escape by removing part of the frame of his cell window with a sharpened spoon and bending a few bars. He went into hiding in The Hague. Agents of MI6 and S.O.E. in the Netherlands did not trust him any longer as they did not believe his story about his escape. They assumed he had intentionally been released by the Germans.

Meanwhile, Sporre had made contact with Schrage. On November 13rd 1941, he and the Dutch MI6 agent attempted to cross the North Sea in an 26 foot canoe with an outboard engine. They never made it to England though. It is assumed they drowned on the way over.

The start of the Spiel

In the night of November 6th to 7th, 1941, S.O.E. agents Huub Lauwers and Thijs Taconis were dropped near Ommen, Overijssel. The agents always jumped out of a bomber of the R.A.F., usually a Short Stirling. The mission of Lauwers and Taconis was not prepared too well. Their ID cards showed flaws, making them immediately recognizable as forgeries and both men wore identical clothes. Lauwers had been recruited by Laming. By the way, Van ‘t Sant had reported in 1941 he and MI6 considered Lauwers unsuitable for posting as his skills as a radio operator would be insufficient. Lauwers also had the disadvantage not to have been in the Netherlands since 1935, hence he had no knowledge of the local situation and had no connections in the country. This was also one of the reasons Van ‘t Sant did not want to send him abroad.

After they had landed successfully, Taconis and Lauwers discovered that the silver coins they had been given were no longer valid. They traveled to Amsterdam together. They attempted to find shelter with one of the persons from Taconis’ pre war circle of friends but they only succeeded after a few attempts. Lauwers’ transmitter appeared not to be working well after landing, hence they did not succeed in contacting London. In mid December, Lauwers traveled to The Hague hoping he could find radio contact there. Only after two months, after a student had found a faulty switch in the transmitter and had replaced it, the unit functioned as desired although its range was less than previously indicated by the S.O.E. officer. On January 3rd, 1942 Lauwers managed to contact London for the first time. This month, the Abwehr already knew someone was transmitting from The Hague. All messages were intercepted by the Funkbeobachtung but they could not be deciphered by the Germans yet.

One of the tasks Taconis and Lauwers had been given was to find out what had happened to Homburg and Sporre. In January they managed to contact Homburg. Lauwers duly reported this to S.O.E. Blizard, the head of S.O.E. indicated Homburg was to return to England. S.O.E. however, could not provide transport for them. Together with two friends, Buizer and De Haas, they fled to England on February 15th, 1942 aboard a trawler from IJmuiden. The three friends hid in the hold. On the high seas, they captured the vessel and forced the crew (assisted by a more than willing skipper) to set course for Great Britain. Homburg was ale to provide the Dutch and British agencies with some valuable information. Buizer and De Haas were recruited by S.O.E.; Homburg entered service with the R.A.F.

Definitielijst

- Abwehr

- Term used for the German military intelligence unit during the WW1 and WW2. From 1935 onwards under command of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. The organisation often came into conflict with other secret services such as the SD and the Gestapo. During World War 2 under Canaris frequently a source for conspiracies against the Nazi regime until in 1943 a major conspiracy by a number of prominent members of the Abwehr was discovered and the Abwehr was placed under command of Himmler. After the assassination attempt on Hitler in 1944, Canaris was discharged and the Abwehr was dissolved. The conspirators and Canaris were prosecuted and in 1945 they were executed atc oncentration camp Flossenburg.

- Engelandvaarders

- People sailing for England. Nickname for Dutch men who tried to get to England by sea after the Germans occupied the Netherlands to continue the battle against the invader. Many died during the voyage which was sometimes undertaken in canoes. Most of the “Engelandvaarders” could report their safe arrival to their loved ones who stayed behind through Radio Oranje by codewords.

- Englandspiel

- “England game”. The game, ironic as it may sound, of espionage and counter espionage between the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the Nazis. This “game” resulted in the death of approximately 54 allied spies.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Sipo

- ”Sicherheitspolizei”. Combination (since 1936) of the Gestapo and criminal police.

Images

Telegrams to London

North Pole

It was Taconis’s task to recruit a group of intelligence agents and saboteurs in the Netherlands. In his attempts he met the veterinarian and Captain of the Reserve C.F. van den Berg, member of the Ordedienst (O.D.), a resistance group mainly consisting of former officers of the navy and army. This Van den Berg had a connection with George Ridderhof, a man he considered a courageous resistance fighter. Ridderhof however was a V-man (stool pigeon) for the Abwehr. Everything Taconis and Van den Berg did was passed on to Herman Giskes, Chief of Referat III of the Abwehr, who was in charge of counter espionage. In January 1942 Lauwers received a message to the effect that weapons were to be dropped for the resistance group of Taconis. This was strange; the group had hardly been established and did not need weapons and explosives. Yet, the drop went ahead as planned. Lauwers and Taconis discussed it with Van den Berg and so Riddehof got wind of it. He forwarded all of it to Giskes. Ridderhof also indicated that probably more agents and supplies would be dropped and that he could funnel all of it into German hands. Initially, Giskes did not attach much value to Ridderhof’s story. He wrote in the margin of Ridderhof’s report where he stated his findings that he could go to the North Pole with his story, hence the code name Operation Nordpol.

V-man Ridderhof meanwhile made himself trusted more and more by Taconis and Van den Berg, among other things because of the details of espionage he reported that looked very dependable and useful but had all been formulated by Giskes though. He also offered to provide a truck to transport the weapons from the drop zone. The dropping took place on March 2nd. One of the two containers could be salvaged, the other landed in the canal. In the meantime, Oberleutnant Heinrich, chief of the Funkbeobachtung knew the location of the transmitter in The Hague.

On March 6th, 1942, Lauwers was arrested at the address of the Teller family in The Hague who had made their home available to the resistance. Lauwers had three coded messages on him he still had to send. After the war he said about it: "Coding is time consuming and that is why I had taken these three telegrams with me. I had not reckoned on being arrested this way." Giskes wanted to start a Spiel right after the arrest. Giskes’ main objective was to control hostile activities; elimination of the agents came second. As the Netherlands had a civil administration instead of a military, the military intelligence agency in the Netherlands was not allowed to arrest or interrogate civilians. It had to leave that to the Sipo, Department IV headed by Kriminaldirektor and SS-Stumbannführer Joseph Schreieder. This department was involved in fighting internal espionage. Cooperation between these two organizations and persons would progress very well. On March 9th, Taconis and the members of the resistance group he had established in the meantime, were arrested in Arnhem by Leo Poos and Marten Slagter, police officers from The Hague and co-workers of Schreieder.

Warnings by Lauwers

Lauwers was transferred to Abwehr HQ in Scheveningen. Giskes asked him if he would work for the Germans. During his training in Great Britain, Lauwers was told, in case of his arrest he was allowed after a while to work for the enemy, if only he would omit his security check. The agent would stay alive this way and England would be notified he was working for the enemy under duress, giving London the opportunity to start an operation of deception by radio. A few hours after his arrest, Lauwers submitted his code to the Germans. He did so when it became clear that Oberleutnant Heinrich possessed exhaustive knowledge of the Britsh codes that were in use; knowledge he had gained from the earlier arrests of Van der Reyden, Zomer and others. According to his instructions and after Giskes had promised not to take Taconis to a German court to have him executed, Lauwers promised to cooperate. After the war, he gave another reason for his cooperation: "When you have submitted your code and start working for them, you are valuable to them and as long as you are, you have a chance to survive."

On March 12th or 15th, Lauwers transmitted the three messages he had drafted and coded before his arrest, including his security check. On March 19th, 1942, he transmitted his first message under German direction. He omitted his security check. At MI6, which until July 1942 received all messages, this was noticed and passed on to S.O.E. Up to then, Lauwers had transmitted 17 messages in freedom in which the security check had been included correctly each time. The head of the Dutch Section, Blizard, assumed however he had omitted the check because of poor equipment, nervosity, forgetfullness or atmospheric interference; hence the contact was not broken. The announced arrival of an agent was postponed however but the dropping of material would go ahead as planned. Lauwers presumed the Britsh secret service wanted to play a game with the Germans. This did happen sometimes. His assumption was confirmed initially by the postponement of the dropping of the agent and later when it turned out the material that was dropped did not amount to much, as for instance the transmitter was missing.

After the war, many have wondered how it could have been possible the British had paid so little attention to the fact that security checks in Lauwers’ messages and in those of other captured agents were missing. As many of the agents were equiped with low power transmitters, many messages did not arrive in London or were garbled. Certainly in cases where the security check consisted of only one character being sent incorrectly, it was very difficult to check whether it had been included or not. In case the check was missing, an investigation was started in each individual case, hence there were no checks made over a longer period. Moreover, the British went on the assumption the security check as a means of identification was insufficient, the reason why S.O.E. attached little value to it. The security checks in use by S.O.E. were of poor quality because of their simplicity. There were no other ways to check if the operator could still be trusted. The "finger print" (the specific way of using the transmission key) of each individual operator was only being recorded from 1943 onwards. In addition this was difficult to verify. This finger print was often distorted by atmosferic interference, the agents were often highly stressed which also led to aberrations. A skillful operator was able to copy someone else’s finger print. S.O.E. mainly judged the messages on their content and in case of the Englandspiel, that appeared dependable. Because the intelligence services were expanding fast, many agents were sent out into the field without having been trained properly. That also applied to the workers at the receiving station. A certain routine and complacency prevailed in the centers were messages were received and decoded. Often only actual and relevant content would be decoded; groups of characters containing the security check were not decoded at all. The workers thought they were able to recognize the operator by his way of transmitting and the rule that copies being sent to the various sections should contain the remark "checked for identity" was often broken.

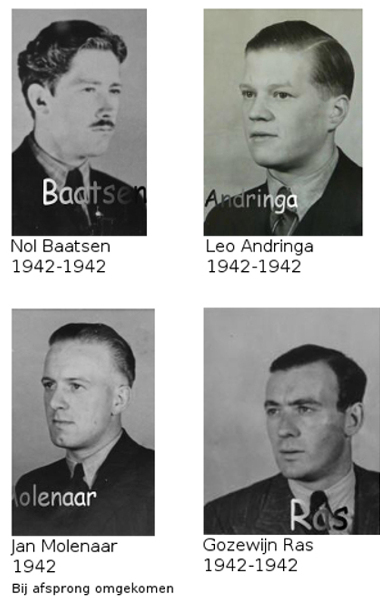

The dropping of Abor

In the night of March 27th to 28th, 1942, the agent Nol Baatsen (code name Abor) was dropped near Kallenkote, Overijssel. V-man Ridderhof, who knew the password provided by S.O.E., was waiting for him. Subsequently he was arrested by the collaborating police officers Poos and Slagter. The Germans informed him that his mission had been betrayed by England. Baatsen was so shocked about this he volunteered many details during his interrogation the next day. Lauwers subsequently refused to play the German game any longer because he did want more agents of the secret service falling in German hands because of him. After Giskes had promised him again, these captured agents would not be executed, Lauwers resumed radio contact with Great Britain. He still presumed, the British were playing a game with the Germans and that also made him continue his cooperation. Until mid November, Lauwers transmitted many messages with an obviously fake security check. He could not omit these altogether as the Germans knew about the use of these signs. Lauwers’ check entailed misspelling each 16th character or a multiple – e.g. 32, 48 – in each message. He had told the Germans his check entailed typing step or stip instead of stop.

On March 29th, 1942, agents Leo Andringa, Jan Molenaar (near Ommen) Gozewijn Ras en Han Jordaan (near Rijssen) were dropped. The operator Molenaar lost his life on landing and his transmitter was damaged. All contacts of these agents went by way of Jordaan and the Germans were eavesdropping on this contact from the beginning. Oberleutnant Heinrich of the Funkbeobachtung soon discovered somebody was transmitting from Utrecht.

In April 1942, without Lauwers being notified, the agents Barend Kloos (April 5th), Hendrik Sebes and Johan de Haas (April 9th) were dropped or taken to occupied Holland by boat. Their contact also went via Jordaan. At the end of April, the British ordered Group Taconis to make contact with De Haas at an address in Haarlem. The Germans managed to locate the address. By passing himself off as a member of the resistance, police officer Poos won the trust of the shopkeeper. As a result, the Germans were able to arrest agents De Haas and Andringa on April 28th. After Schreieder had told De Haas he had been betrayed, the latter was so shocked he volunteered much information. He declared for instance that the agents who had been dropped would meet in a bar in Utrecht on May 1st. Andringa went there accompanied by Poos. The building was surrounded in advance by officers of the SD. Agents Ras en Kloos were arrested, Jordaan and Sebes managed to leave the bar in time, as they suspected danger. During the arrest, the Germans found a notebook with a telephone number that proved to belong to the operator. Anton van der Waals, another V-man working for Schreieder, subsequently called Jordaan and indicated he was making contact on behalf of Ras. The agent promised to meet the caller. He had some suspicion but it disappeared because Ton, the bogus parachutist from London, appeared dependable. They agreed to meet once again at the railway station in Rotterdam. Jordaan passed the phone number of Sebes to Van der Waals as he had to be "warned" as well. Afterwards, Jordaan was arrested by officers of the SD. Van der Waals (Bio van der Waals) ordered Sebes, allegedly on behalf of Kloos, to come to Rotterdam. He was arrested there as well on May 9th.

After his arrest and in accordance with instructions, Jordaan submitted his code. He really had little choice. The Germans already knew the system and moreover, he had the poem containing the code in his pocket. But he also omitted his security check. A first message was transmitted by a German operator without Jordan’s check. Jordaan’s warning was not understood as such by S.O.E. On the contrary, he was ordered to instruct an operator in the Netherlands in the use of the security check. It was also pointed out to him, he was not to forget his own check. More or less forced to do so, Jordaan submitted his security check to Giskes.

Caught

Lauwers attempted to warn in more than one way than the incorrect application of his security check. He and Jordaan were given the messages they had to transmit beforehand. These had been drafted by Giskes. During transmission, they were watched over by a German operator, hence they could not send something quite different from what the Germans had given them. According to Lauwers, he mentioned the word ‘caught’ in his telegrams, initially in groups of characters such as ‘ght’ and ‘cau’, later in full. In August, he is said to have included the words ‘worked with Jerry’ in his message. Whenever there was a frequency change, the operator notified the recipient using a code of three characters, which Lauwers replaced by ‘ght’. He replaced the notification: "I have no more messages for you, QRU by ‘cau’. Transmitting was done in groups of five characters. Lauwers transmitted the characters ‘caugh t’ a few times, followed by a sign he had made a mistake. He hid the warning ‘worked with Jerry’ in the jumbled characters, meaningless characters at the beginning and the end of each message. Lauwers was not able to transmit the second part of his warning as the Germans suspected he had made alterations to the message he was to transmit on their orders.

In his ‘Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog, deel 9’ (The Kingdom of the Netherlands in World War Two, part 9) historian Loe de Jong mentioned a few reasons why the warnings by Lauwers were not considered as such. The messages were received by young operators. They only wrote down the groups of characters, decoding was done by someone else. The decoders had the coding system, the prevalent code and the security check at their disposal. They decoded the message and checked the text. They probably paid no attention to the jumbled characters and the signs that indicated a change of frequency. The characters ‘ght’ and ‘cau’ were wide apart. It is well possible that the decoders did not see the word ‘caught’ in the characters ‘c a u g h t’. The same applied to ‘worked with Jerry’ which appeared in the jumbled characters and was probably not decoded or understood as such at all. The jumbled characters were not included in the final transcript of the messages either that were passed on to the intelligence sections of the various countries. These messages started with the number of the operator and ended with ‘end’. The decoders probably considered the group of characters a mistake. During transmission a reply was sent: ‘message understood’ but that was standard procedure after a group of characters had been received. Because the group of characters was considered a mistake, it was also possibly crossed out in the message that was passed on to the various sections. After the war, the telegrams were burned by the British so there is no evidence for Lauwers having actually issued warnings. In August 1945, Dobson, the successor of Bingham and Blizard as chief of the S.O.E. Dutch declared telegrams had been received without the security checks.

In October 1942, Lauwers was transferred to the Polizeigefängnis und Untersuchungs Gefängnis (Police and investigation prison) Haaren in Noord-Brabant, thereafter the messages were sent by a German operator.

In May 1942, the Group Taconis/Lauwers had also been ordered to contact agent George Dessing, who had been dropped in February, in a bar in Amsterdam. Escorted by Poos, Andringa went there. He managed to warn Dessing unnoticed, enabling him to get away safety.

On May 22nd, agents Ernst de Jonge and Leen Pot were arrested, Jan Emmer on May 30th. In May, operators Felix Ortt and Evert Radema were arrested by the SD. These agents worked for MI6. They had been dropped in connection with Operation Contact Holland. This entailed secret agents were to be put ashore at night by boat near the Scheveningen Pier; also persons, whose presence in London was desired, were to be picked up using this route. Through the resistance web in the Netherlands, they contacted S.O.E. agents who were controlled by the Germans, hence they could be arrested also. Giskes and Schreieder had too little information on MI6 to convince these agents they had been betrayed, nor did the Germans succeed in setting up a Funkspiel via their radios as MI6 saw through the ruse. This organization did pay sufficient attention to the security checks.

Definitielijst

- Abwehr

- Term used for the German military intelligence unit during the WW1 and WW2. From 1935 onwards under command of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. The organisation often came into conflict with other secret services such as the SD and the Gestapo. During World War 2 under Canaris frequently a source for conspiracies against the Nazi regime until in 1943 a major conspiracy by a number of prominent members of the Abwehr was discovered and the Abwehr was placed under command of Himmler. After the assassination attempt on Hitler in 1944, Canaris was discharged and the Abwehr was dissolved. The conspirators and Canaris were prosecuted and in 1945 they were executed atc oncentration camp Flossenburg.

- Englandspiel

- “England game”. The game, ironic as it may sound, of espionage and counter espionage between the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the Nazis. This “game” resulted in the death of approximately 54 allied spies.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Sipo

- ”Sicherheitspolizei”. Combination (since 1936) of the Gestapo and criminal police.

Images

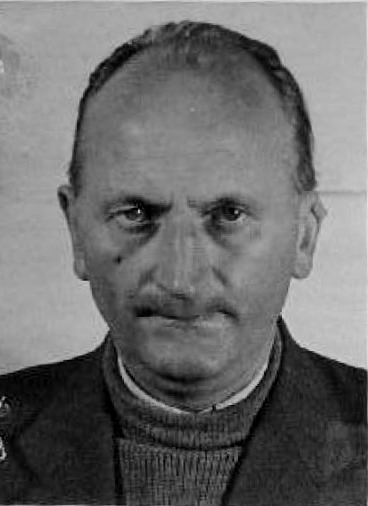

Hermann Giskes, Chief of Referat III F of the Abwehr, charged with counter espionage. Source: Wikipedia.org.

Hermann Giskes, Chief of Referat III F of the Abwehr, charged with counter espionage. Source: Wikipedia.org. Kriminaldirektor and SS-Sturmbahnführer Joseph Schreieder, Sicherheitspolizei (Sipo), Department IV Source: Englandspiel.eu.

Kriminaldirektor and SS-Sturmbahnführer Joseph Schreieder, Sicherheitspolizei (Sipo), Department IV Source: Englandspiel.eu.British-Dutch and German procedures

Plan for Holland

On April 25th, Callin Gubbins, chief of S.O.E., had made a proposal for a new S.O.E. operation in the Netherlands to Colonel Mattheus de Bruijne, successor of François van ‘t Sant who had been sacked. This ‘Plan for Holland‘ entailed the establishment of an army of saboteurs, 1,070 strong. In the event of an Allied invasion, this force was to sever the enemy’s communication lines by launching guerilla raids on objects such as railways, air fields, bridges, telephone and other lines of communication in his rear areas. To this end, the country was to be divided into 17 districts. The leaders of these districts and other high ranking officials would be flown in. Part of the army of saboteurs was to be recruited in the Netherlands. De Bruijne approved. He proposed to contact the resistance group, the O.D. Initially H.M. Queen Wilhelmina and the government were against acts of sabotage because of the inevitable reprisals. Nonetheless, the government approved the plan in early May.

Progress of the game

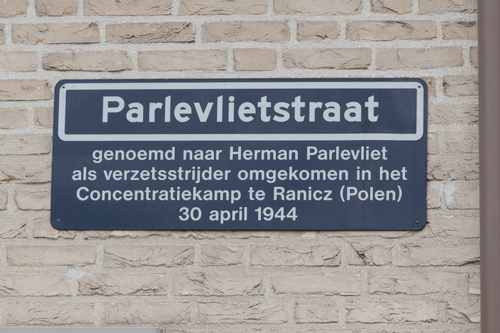

From May 1942 onwards, London announced the arrival of agents via the channels of Lauwers, Jordaan or another agent under German supervision. As it proved difficult for British pilots to locate the designated drop zones, a system of reception committee was introduced that would stake out the drop zones with light signals. As these reception committees were under German supervision, all agents dropped fell in their hands. The first two to be arrested were Herman Parlevliet and Toon van Steen. They had been dropped on May 29th near Kallenkote. Among other things, they had with them the transmitter and codes for Leo Andringa who had already been arrested by the SD at that time. In this way, the Germans were literally offered a third transmitter for the Spiel on a platter. Via Jordaan’s connection they received yet another one. Blizard, chief of S.O.E. Dutch ordered Van Steen and Parlevliet from London to recruit an operator in Limburg for whom transmitter and codes would be dropped. Via the channels of the Spiel, the Germans made London believe a dependable person had been found within the resistance. In reality, a German operator of the Ordnungspolizei was operating this set.

The Dutch Section made the mistake of spreading the contacts over multiple channels and seeing to it the cells made mutual contact. Such a method violates the unwritten rule of secret work. Announcing the arrival of the agents also made things very easy for the Germans. Writer and researcher of the Englandspiel, Jo Wolters talks about unnecessary and risky behavior. It may very well have been just incompetence of the workers on the Dutch Section.

In the night of June 22nd to 23rd, the agent Jan Jacob van Rietschoten and operator Jo Buizer were dropped near Holten. During the interrogation after his arrest, Buizer submitted his code and his security check. It was the fifth channel of the Englandspiel.

Van Steen and Parlevliet were ordered by S.O.E. Dutch to blow up the locks in the Juliana canal. Giskes suspended the contact via this channel. He made it seem like the operation had failed and that the agents had either been arrested or gone into hiding. Actually, this was the only choice he had. He could not really have the locks blown up. If the locks were not destroyed and contact was continued through this channel, it would have aroused suspicion in S.O.E.

In the night of June 26th to 27th, the intended leader of the group, George Jambroes and operator Sjef Bukkens were dropped near Kallenkote. The reception committee consisted of the collaborating policemen Poos and Slagter. The Germans found the code and probably Bukkens’s security check as well after his arrest. Jambroes was not properly trained for his mission. Because the math and physics teacher Jambroes had served in the Dutch army during in early May 1940, S.O.E. thought a crash course of 14 days would be ample training for him. After the interrogation, the German code expert Ernst May, concluded that Jambroes was unsuitable as a secret agent because the ties he had with his family were too strong. The Germans would consider more parachutists they had arrested in connection with the Englandspiel unsuitable for the role of secret agent. They thought most of them were adventurers or people suffering from homesickness.

Arresting the dropped agents by the Germans usually went ahead without any violence. Poos and Slagter were waiting for them and they usually made some small talk first. The agents thought they were dealing with trustworthy fellow countrymen and so volunteered much information. Subsequently the agents were told it would be better if they would take off their jump suits. At that moment they were overpowered and hand cuffed. Thereafter they were transported to The Hague (later on to Driebergen) where Schreieder welcomed them in the most friendly manner. The Germans told the agents they had been betrayed by London. They were exhaustively interrogated by Schreieder and Ernst May. After a few days in The Hague, the captured agents were then transferred to Camp Haaren.

The impression was always made that the agent was the first S.O.E. agent who was arrested. The Germans apparently knew everything about their mission. They mentioned details about the task to be executed but also about the training they had undergone, for instance about their instructors or the color on the wall of a specific class room. After all this, the arrested men usually cooperated rather willingly. This way they volunteered even more information, which Giskes and Schreieder would subsequently use to browbeat the next arrested agents and so on. This explains for instance why Jambroes volunteered so much information because he thought the Germans already knew everything.

Giskes drafted the telegrams and selected the drop zones. Schreieder picked up the men and the material. He interrogated the agents and was responsible for their imprisonment and transport.

Results

The Germans were very proud of the results of their Englandspiel. Schreieder reported about it to Wilhelm Harster, Befehlshaber der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD in the Netherlands. He in turn reported to Hanns Rauter (Bio Rauter), Höhere SS und Polizeiführer in charge of all police and intelligence services in the Netherlands. Rauter forwarded the information to Berlin and to Heinrich Himmler, Reynhard Heydrich (chief of the R.S.H.A.) and his successor Ernst Kaltenbrunner (Bio Kaltenbrunner) as well. Even Hitler (Bio Hitler) seemed to have shown interest in the Englandspiel. At the end of 1942, Himmler and Heydrich (Bio Heydrich) paid a visit to the Netherlands. They had a meeting with the arrested Jordaan. They also approved the way Giskes and Schreieder had proposed to continue the Englandspiel. In a letter to Heinrich Himmler (Bio Himmler), dated July 7th, 1942, Rauter wrote that the Allied invasion would probably take place in the Netherlands and he hoped to find out the exact date of the invasion via the Englandspiel.

The Germans soon gained knowledge of the details of the Plan for Holland and gave the impression that the build up of the secret army was progressing fast. Jambroes and Bukkens had detailed instructions for the resistance with them about the intended organization of the secret army. The plan was not in code so the German could read it easily. This was a big mistake, as the British did admit after the war. Jambroes was to make contact with various resistance groups (O.D. and I.D., intelligence service) and forward the instructions from the government in exile to them. As soon as his task was completed, he was to return to England. According to the British, phase A of the plan, which entailed establishing contacts, recruiting personnel, forming districts and selecting reception committees was completed in early 1943.

In hindsight, a number of researchers considered the order: the agents were to contact the OD, a weird choice. In mid 1942, the O.D. had been all but dismantled by the Germans. A lot of arrests had taken place and dozens of members had been executed. London can hardly be blamed for this choice though. In 1942 the Dutch government and the secret services suffered from a huge shortage of information. The order to make contact with the O.D. was in fact based on no more than a five months old report by Engelandvaarder and member of the O.D. Gerard Dogger. Based on that, it was assumed the O.D. was a large and dependable resistance group. In Switzerland, Dogger had heard rumors though to the effect that a number of members had been arrested but he thought the organization as such still existed.

Definitielijst

- Englandspiel

- “England game”. The game, ironic as it may sound, of espionage and counter espionage between the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the Nazis. This “game” resulted in the death of approximately 54 allied spies.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

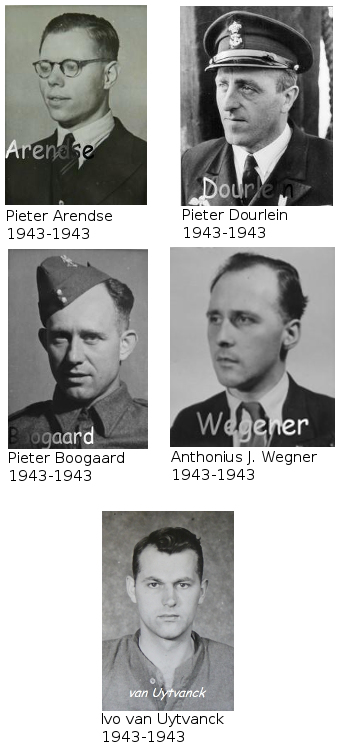

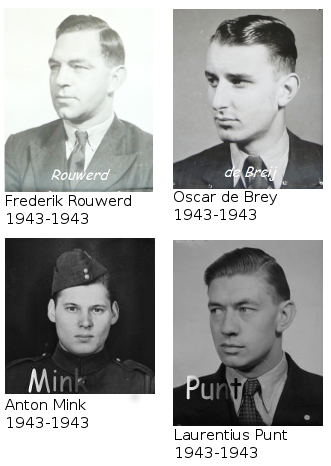

Colonel Mattheus de Bruijne, successor of François van 't Sant as head of the Dutch Centrale Inlichtingendienst in London. Source: Englandspiel.eu.

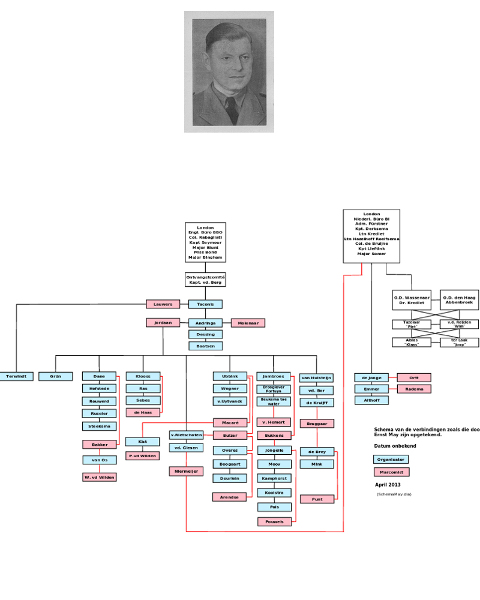

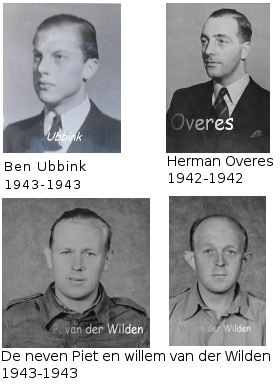

Colonel Mattheus de Bruijne, successor of François van 't Sant as head of the Dutch Centrale Inlichtingendienst in London. Source: Englandspiel.eu. Agents of the Englandspiel with the date of their arrival in the Netherlands and of their arrest Source: Englandspiel.eu.

Agents of the Englandspiel with the date of their arrival in the Netherlands and of their arrest Source: Englandspiel.eu. Wilhelm Harster, Befehlshaber der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD in the Netherlands (left) and Hanns Albin Rauter, Höhere SS und Polizeiführer in charge of all German police andintelligence services in the Netherlands (right). Source: Wikipedia.org.

Wilhelm Harster, Befehlshaber der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD in the Netherlands (left) and Hanns Albin Rauter, Höhere SS und Polizeiführer in charge of all German police andintelligence services in the Netherlands (right). Source: Wikipedia.org.Effects on the Dutch resistance

Operation Feather

On July 24th, 1942, operator Gerard John van Hemert landed near Holten by parachute. He had the order for Operation Feather with him which was to be launched by Group Taconis. After his arrest, Van Hemert did not submit his security check. His radio was taken over by a German operator. London made a note on Van Hemert’s telegrams that the security check was missing; nonetheless, contact with him was not broken. Operation Feather entailed an attack to be launched by the Dutch resistance on the radio station in Kootwijk in Gelderland. This was in use by the Germans to communicate with the U-boats deployed in the battle in the Atlantic. Lauwers signaled the attack had been launched on August 9th but had failed because the group had encountered strong resistance and had got trapped in a minefield. Actually, the Germans had launched a bogus attack. They had been firing blank ammunition for a few minutes.

The next day, an article was published in the Dutch newspapers. They reported an attack had been launched on the radio station in Kootwijk but this had been repulsed and a number of attackers had been arrested. After having received Lauwers’ message, Blizard informed him that Taconis had even been awarded with a British decoration for the courageous attack. The agent code named Fred/Anton (actually Anton van de Waals) with whom Taconis allegedly would have cooperated, was ordered by S.O.E. Dutch to come to England in order to take a course in sabotage. Giskes and Schreieder considered sending Van der Waals to England for real. They abstained from this however because they already knew everything about the organization and training of agents in England. When the S.O.E. leadership continued asking for Fred’s transfer, Giskes and Schreieder indicated Van der Waals had been arrested in Paris.

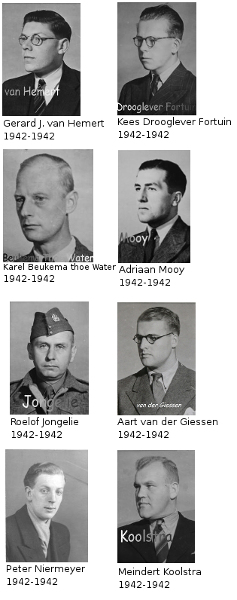

In the night of September 24th to 25th, operator Kees Drooglever Fortuin, the district chiefs Karel Beukema thoe Walter, Adriaan Mooy and operator Roelof Jongelie were dropped near Rijssen (Overijssel) and Balloo (Drenthe). Beukema faced the same problem many other agents did. He had not been in the Netherlands for a long time (he had left for Indonesia in 1935), hence he had few connections in the Netherlands. This made him unsuitable really for posting but S.O.E. thought otherwise. The codes of Drooglever Fortuin and Mooy fell in German hands right after landing but Mooy did not submit his security check. As Jongelie refused to provide any information, the Germans indicated, via the radios of the Spiel, that Jongelie had been injured on landing and had died in October. They were afraid that if orders for him came through from London, they might not completely understand them, which might arouse suspicion at S.O.E.

The Spiel continues

On September 24th, 1942, Charles Blizard was succeeded by his deputy Major Seymour Bingham as chief of S.O.E. Dutch. Based on what Dutch colonel De Bruijne had written, Bingham painted a far too positive picture of developments in the Netherlands. De Bruijne urged Jambroes to come to England in order to report in person on the progress of the Plan for Holland. This was impossible of course as Jambroes had been imprisoned by the German and they just could not let him go to England. Subsequently, Giskes had a message sent, stating Jambroes was indispensable in the Netherlands. Bingham kept urging however. The Germans sent him a message stating he had lost his life in a firefight on November 8th, 1942. Thereupon, Bingham appointed Beukema the new leader of the Plan for Holland.

In the night of October 1st and 2nd, agent Aart van der Giessen was dropped near Steenwijk (Friesland). Among other things, he had an identity card, an improved forgery with him and money for MI6 agent Peter Niermeyer who had already been dropped on March 29th. During his arrest this evidence fell in German hands. Van der Giessen had the address where he was to deliver this identity card. Subsequently, Niermeyer was arrested himself in Amsterdam on October 6th. He was the last agent still operating in freedom in the Netherlands. The Germans attempted to use his radio. As the security check was missing in the first message sent by them, Mi6 saw through it and broke contact.

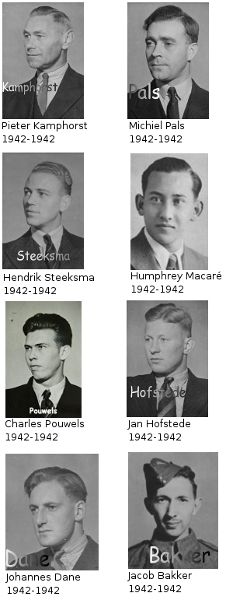

In the night of October 21st to 22nd, district chiefs Meindert Kooistra, Pieter Kamphorst and operator Michiel Plas were parachuted in the vicinity of Voorthuizen (Gelderland). They were followed by district chief Hendrik Steeksma and operator Humphrey Macaré, dropped near Steenwijk; on October 24th, district chief Jan Hofstede and operator Charles Pouwels were dropped near Holten and on October 28th, district chief Johannes Dane and operator Jacob Bakker were dropped. All their radios would be deployed in the Englandspiel which now consisted of 12 channels. The R.S.H.A. (Reichssicherheitshauptamt, head office of state security) was informed by Rauter that apart from these agents, 18 ton of material had fallen in German hands. Bingham, the successor of Blizard had a far too positive idea of the situation in the Netherlands which was proved by the fact that in three nights he had 18 ton dropped. If those weapons had actually been received by 8the persons they were destined for, the question arises if the resistance would have been able to distribute everything on time.

In the night of November 28th to 29th, district chief Arie de Kruyff and operator George Ruseler were dropped near Ugchelen (Gelderland), followed on November 30th by chiefs Ben Ubbink and Herman Overes near Leersum (Utrecht). For Ruseler, born in Indonesia, this was his first encounter with the Netherlands. After just five days of imprisonment, Ubbink submitted his security check as he assumed everything had already been betrayed by London (the Germans already knew so much) and because he wanted to stay alive.

Code name Felix

After this, things remained calm for a while. Giskes and Schreieder were getting afraid London had seen through the game. This was not the case however as the arrival of Felix was announced, the alias of Trix Terwindt. After Terwindt had reached England via Switzerland and Spain in August 1942, she was approached by Captain Airey Neave, a member of MI9. This agency concerned itself with getting Allied pilots back to England who had been shot down over occupied Europe. Because of her sound contacts, the former flight attendant was considered capable to set up a network in the Netherlands that could help in opening an escape route for pilots to neutral territory. It was expected she could complete this task within three months. Thereafter, she was to return to England herself via the new route. MI9 itself was unable to drop agents and so, S.O.E. Dutch was asked for help. S.O.E. announced the arrival via one of the "infected" channels. The Spiel replied it would bid this "most courageous woman" a warm welcome. Beforehand, she was given a list of addresses by MI9 of persons she could approach. In the night of February 13th to 14th, 1943, Terwindt was dropped near Kallenkote. When asked for it, she handed her list of addresses to Poos and Slagter who had been waiting for her. She was to follow the instructions of the reception committee as ordered by London. The problem was, she had been warned about these persons in advance. S.O.E. knew their names because Engelandvaarders had warned against these two notorious traitors but S.O.E. did not know what they looked like. Consequently she was arrested. She did not submit her code and the Germans were not able to decipher it either. The persons Terwindt should have contacted, among them Cees Smit, were arrested by the Sipo as well.

Infiltration in the resistance

On February 17th, district chief Cornelis van Hulsteijn, saboteur Klaas van de Bor and operator Cornelis Braggaar made their jump over the Netherlands. They were followed on February 19th near Holten by agents Jan Kist and Gerard van Oss and the operators Pieter and Willem van de Wilden. Van de Bor was wanted in the Netherlands for having murdered a German soldier. S.O.E. knew this but he was dropped nonetheless. After his arrest he was brutally tortured. Kist and Van Oss were tasked with preparing an escape route for Beukema, the leader of the Plan for Holland. Kist was ordered by London to contact the Belgian resistance group Dienst Wim. By passing himself off as a friend of Kist, Van der Waals managed to infiltrate this group which was dissolved on July 20th, 1943. Bingham ordered Kist to report in England. Two V-men passed themselves off to the resistance as Kist and his companion and asked S.O.E. for a dependable address in Paris. In this way, the Prosper network (a French resistance group) was infiltrated. On June 10th Kist himself was allegedly arrested in Paris.

Using the information generated by the Englandspiel, the German secret services were able to infiltrate various Dutch resistance groups. Using a picture of the daughter of journalist Meijer Sluijser who lived in London, Anton van der Waals, using his alias Anton de Wilde, made contact with persons within the circle of S.D.A.P. leader Koos Vorrink at the end of 1942. This picture had been used before by S.O.E. agent Dessing as his introduction to the S.D.A.P. leadership in Amsterdam. When these persons around Vorrink asked for an additional identification of De Wilde by means of an announcement on Radio Oranje, it was taken care of via one of the channels of the Englandspiel. Van der Waals told Vorrink London wanted to know the names of the members of the National Committee, the daily leadership of the Grootburgercomité (citizens commission, some sort of illegal provisional government in the Netherlands), consisting of politicians of all pre war parties and businessmen. London had indeed submitted a request like that via Van Hemert’s channel, who was in custody since July 1942. Vorrink mentioned the names of these persons, resulting in their arrest by the SD on April 1st and 2nd. Using Vorrink, Van der Waals managed to infiltrate numerous resistance groups, resulting in more than 150 arrests.

Definitielijst

- Engelandvaarders

- People sailing for England. Nickname for Dutch men who tried to get to England by sea after the Germans occupied the Netherlands to continue the battle against the invader. Many died during the voyage which was sometimes undertaken in canoes. Most of the “Engelandvaarders” could report their safe arrival to their loved ones who stayed behind through Radio Oranje by codewords.

- Englandspiel

- “England game”. The game, ironic as it may sound, of espionage and counter espionage between the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the Nazis. This “game” resulted in the death of approximately 54 allied spies.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Sipo

- ”Sicherheitspolizei”. Combination (since 1936) of the Gestapo and criminal police.

Images

The end nears

The last drops

In the night of March 8th to 9th, operator Pieter Arense and chiefs Pieter Dourlein and Pieter Boogaard were dropped near Ermelo (Gelderland). All agents dropped by S.O.E. had been ordered to follow all instructions by the reception committee on landing. Dourlein gave the address where he was supposed to report to Poos and Slagter. He also handed over his pistol when asked. Thereupon he was arrested.

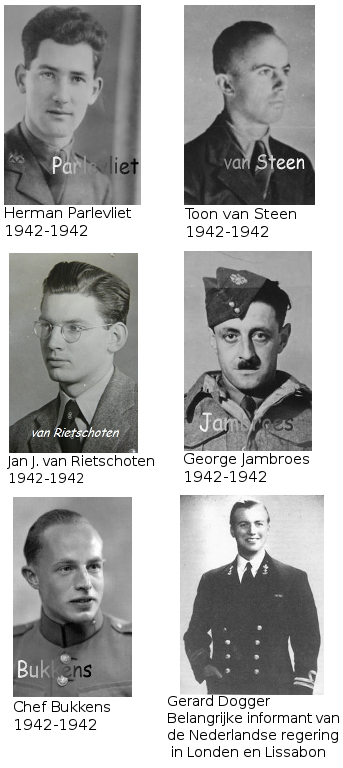

On April 22nd, district chiefs Anthonius Johannes Wegener, Ivo van Uytvanck and Frederik Rouwerd were dropped near Garderen (Gelderland). The last agents who jumped over the Netherlands in connection with the Englandspiel were chief Oscar de Brey and the operators Anton Mink and Laurentius Punt in the night of May 21st to 22nd, 1943.

After Punt’s arrest, Schreieder organized a big party in Scheveningen. A few persons, among them Ernst May, were given a financial reward by Wilhelm Harster for their good work. The Abwehr however was not invited to the party.

First suspicion in London

De Bruijne asked for the urgent transfer of the leader of the Plan for Holland to England. Giskes and Schreieder pretended Beukema had lost his life on June 15th, 1943 in France. Subsequently, operator Cees Drooglever Fortuin was named the new leader of the Plan for Holland. As Beukema was unable to return to England and as De Bruijne was receiving many messages about the increasing number of arrests in the Netherlands, he refused to dispatch any more agents.

From the end of May 1943 onwards, De Bruijne – meanwhile head of the Bureau Militaire Voorbereiding Terugkeer (M.V.T., Military Preparation for Return) refused to allocate agents to S.O.E. any longer as he suspected danger. Not one of the agents had returned to England, although that had been the intention of the Plan For Holland from the beginning. He also received alarming messages about the S.O.E. web in the Netherlands from Jonkheer Pieter Six, the new leader of the O.D. On June 20th, 1943, Six sent a warning that had reached him through all kinds of roundabouts and originated from Pieter Dourlein who was detained in Haaren. This message was presented to De Bruijne on June 23rd. The message was not entirely clear however: "To Colonel De Bruijne / stop / eight parachutists, including Dourlein and Arabe arrested weeks ago, code slagwoord, friend Marius known / stop / end". It was not clear who was meant in the message. When Six was asked for more details, he replied: Message is from Haaren, must be sufficient for colonel de B, further details unknown". De Bruijne probably did not know what was meant by Haaren. He probably now understood that a number of agents had been arrested but in his opinion, and of the British, the organization as a whole still existed in the Netherlands, as was evident from the appointment of Drooglever Fortuin as the new leader of the Plan for Holland. In the night of September 22nd to 23rd, Bingham had the agent Cnoops jump over northern France without any notification. Bingham obviously had lost faith in reception committees. Cnoops was to get clarity about the situation in the Netherlands and then return to England. Cnoops spent a few weeks in the country but failed to get a clear picture.

Dropping of agents may well have been suspended though but weapon drops continued for the time being. The R.A.F. lost 12 aircraft and 83 men during those flights over the Netherlands. The percentage of losses over the Netherlands amounted to more than 10% while 1 to 3% was normal for such missions. The R.A.F., considering these figures, suspended these flights as well. In September 1943 however, the Dutch Section still had full confidence in the organization in the Netherlands, as appears from the exchanged messages and the contact still being maintained.

On August 4th, Giskes gave the impression the saboteurs had scored a great success by sinking a German vessel, loaded with aircraft parts, on the New Meuse in Rotterdam. Actually, this concerned an old barge, loaded with wrecks of aircraft that had intentionally been blown up by two members of the Abwehr. Also a few, unimportant railway tracks were damaged and Giskes intentionally let a few British pilots escape to Spain. He did this in order not to arouse suspicion in England. In the same month, someone was actually sent to England. It was Sergeant H. Knoppers who had been approached by V-man George Ridderhof alias George van Vliet. Knoppers had an indirect contact with the Dienst Wim in Belgium and so Ridderhof managed to contact him. Knoppers himself was not aware of his part in the game. He thought he would be sent to England to receive instructions from the Dutch government in exile. He was given a number of reports, allegedly from the S.O.E. group in the Netherlands but actually, they were drafted by Giskes and Schreieder. Despite Knoppers being unable to provide useful information, Bingham saw confirmation in his arrival that everything was still all right in the Netherlands anyway. In August 1943, Bingham ordered the S.O.E. team to execute 12 prominent members of the N.S.B. (Dutch National socialist party). The Spiel indicated through its channels, this would lead to severe retaliations, hence the plan was abandoned.

In the night of October 2nd to 3rd, 1943 again two agents were dropped, J. Grün and J.D.A. van Schelle. These agents were not dropped in connection with the Plan for Holland. They were to contact Van Vliet (Ridderhof) who helped Van Schelle escape to England along an escape route running through Belgium, France and Spain to England. Over there, the trustworthiness of Van Vliet was already in doubt. In the autumn of 1943, Captain Jan Somer, head of the Intelligence Office warned Bingham and De Bruijne more than once, things were not right in the Netherlands. Moreover, more messages were coming in about a certain Anton de Wilde (Anton van der Waals) who pretended to work for the Dutch secret services but who was unknown in London.

Escape from Camp Haaren

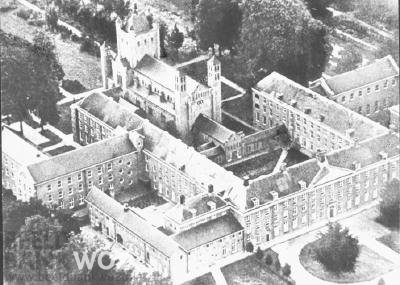

All agents, arrested in connection with the Englandspiel, were detained in Camp Haaren in Noord-Brabant. The prisoners in this former grand seminar were treated rather well generally. They had enough food, they were not abused and also received cigarettes. They were housed on the second floor of the building. In August 1943, 56 agents were imprisoned here, 48 of the S.O.E. and 8 of MI6. They were completely separated from the other inmates. Nonetheless, they kept in touch with one another and other inmates on the floor below through knocking signals. The first attempt at escape was by Aart van der Giessen. He managed to get out of his cell but he was stopped at the back entrance of the prison. Hereafter, the Germans ordered the inmates to lay their clothes and shoes in the corridor at night.

Ben Ubbink and Peter Dourlein escaped in the night of August 29th to 30th, 1943. They managed to squeeze through the window above the cell door; initially they hid in a closet and later on in the bathroom of the guards. At 00:30, under cover of darkness and a violent thunderstorm, they wriggled through the bathroom window. To descent, they used a rope, 40 feet long, made from burlap straps of their beds. They crawled through and over a number of barbed wire fences and a shallow moat. They were given shelter in the Capucijner Convent in Tilburg. One of the priests of the local church of St. Anthonius made them contact local resistance man Frans van Bilsen. He offered them temporary shelter in his home in Tilburg. Right after the escape, Giskes, following a suggestion by Schreieder, sent a telegram to London stating that two agents of the S.O.E. network, Ubbink and Dourlein, had been arrested by the Gestapo; had turned double agents and were now spying for the Germans. These agents were now on their way to London.

Dourlein and Ubbink wanted to have a telegram sent but they gave it to a V-man who of course did not send it. Later on, when they had finally managed to contact S.O.E., London indicated they had to try and reach England by themselves. On November 10th, they were taken across the Belgian border by Van Bilsen.

Definitielijst

- Abwehr

- Term used for the German military intelligence unit during the WW1 and WW2. From 1935 onwards under command of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. The organisation often came into conflict with other secret services such as the SD and the Gestapo. During World War 2 under Canaris frequently a source for conspiracies against the Nazi regime until in 1943 a major conspiracy by a number of prominent members of the Abwehr was discovered and the Abwehr was placed under command of Himmler. After the assassination attempt on Hitler in 1944, Canaris was discharged and the Abwehr was dissolved. The conspirators and Canaris were prosecuted and in 1945 they were executed atc oncentration camp Flossenburg.

- Englandspiel

- “England game”. The game, ironic as it may sound, of espionage and counter espionage between the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the Nazis. This “game” resulted in the death of approximately 54 allied spies.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

1, 2 Agents of the Englandspiel with the date of their arrival in the Netherlands and of their arrest Source: Englandspiel.eu.

1, 2 Agents of the Englandspiel with the date of their arrival in the Netherlands and of their arrest Source: Englandspiel.eu.Consequences

The end of the Englandspiel

They arrived in Bern on November 20th, 1943. General Aleid van Tricht, Dutch military attaché in Switzerland, sent a message to London from the consulate. In this comprehensive telegram, Ubbink and Dourlein testified that the whole organization was in German hands. The assumption was made that Bingham might be a traitor. Colonel De Bruijne trusted the telegram and was now convinced that something was wrong. His British colleague did not share his view. Dourlein and Ubbink reached Spain on December 16th. Here they drafted a report for Jan Somer, head of the Intelligence Office. On February 1st, 1944, they arrived in London from Gibraltar; S.O.E. immediately arrested them on charges of treason and they were interrogated extensively. Ubbink contradicted himself a few times because some details were no longer clear on his mind. To the British, this made him suspicious. The fact they sided with Frans van Bilsen aroused suspicion as well. Shortly before, London had been warned of this person because he was suspected of working for the Germans. This was not true but nonetheless, it was to turn out fatal for him as he was executed on January 19th, 1944 by members of a resistance group from Venlo. Meanwhile in London, a plan was drafted by Colonel de Bruijne to liberate all arrested agents in Haaren but, according to Dutch historian Loe de Jong, this was more out of a sense of guilt than of reality.

On May 23rd, 1944, Dourlein and Ubbink were imprisoned in Brixton jail. Colonel de Bruijne and Prince Bernhard pleaded the British to release them. They were set free in mid June. Callin Gubbins, chief of the S.O.E. offered his excuses for their treatment. They were downgraded by the Dutch Naval Command: Dourlein from sergeant to corporal and Ubbink from lieutenant to sergeant, as they weren’t operating in the field anymore. Thereupon, Ubbink left the navy to become steersman in the merchant navy, Dourlein became air gunner in a Lockheed Hudson of 320 Squadron.

On February 5th, 1944, it dawned on the Germans that the British were aware of the Englandspiel. Agent Garrelt van Borsum Buisman of the Intelligence Office was arrested in Amsterdam that day. He had a number of old messages with him. The Germans already had their suspicions as the messages they were receiving through the 10 channels of the Englandspiel were becoming increasingly meaningless. On April 1st, 1944, Giskes transmitted this message in plain language on all channels, officially ending the Spiel:

"To (the SOE section chiefs) Messrs Blunt, Bingham and Successors Ltd.

You are trying to make business in Netherlands without our assistance. We think this rather unfair in view of our long and successful co-operation as your sole agent. But never mind whenever you will come to pay a visit to the Continent you may be assured that you will be received with the same care and result as all those who you sent us before. So long."

Initially, Giskes wanted to include in the message that the prisoners were still alive but his superiors forbade him to do so. The telegram was addressed to Blizard, who had been promoted in the meantime and Bingham, who had been transferred to Australia. Major Richard Dobson now headed the Dutch section.

Following the disaster of the Englandspiel, the MVT was dissolved. The tasks of this organization were transferred to the Bureau Bijzondere Opdrachten (B.B.O., Office of Special Tasks, established in 1944), and the Bureau Inlichtingen (Intelligence Office).

The fate of the agents

In the night of November 22nd to 23rd, 1943, another three agents escaped from Haaren: Wegner, Van Rietschoten and Van der Giessen. Following this second escape, responsibility for the prisoners was taken away from Schreieder and handed over to SS-Sturmbannführer Erich Deppner, chief of the Abteilung Gegnerbekämpfung of the S.D., in charge of fighting the resistance. Deppner had all the remaining prisoners transferred to the Huis van Bewaring (temporary prison for those awaiting trial) in Assen. Urged by Schreieder, Lauwers, Jordaan, Terwindt, Van der Reyden and Terlaak stayed behind in Haaren as they were needed for the Englandspiel. Later on, Terlaak was transferred to Assen as well.

After his escape, Wegner attempted to reach Switzerland. He was impeded by the fact that the Underground offered him little assistance. As the Dutch resistance had received word from London, not to trust the organization any longer they were very wary to help Wegner. He did manage to cross the border into Belgium but in December 1944 he was arrested by the Germans in Liège. Agents Van Rietschoten and Van der Giessen drafted a message that was forwarded to London by B.B.O. agent Bob Celosse. They wanted to go to Spain and to this end they approached a resistance group. Unfortunately, they contacted Christiaan Lindemans, a V-man recently recruited by Giskes. Lindemans betrayed the two agents to the Germans. They were arrested on May 5th, allegedly while being checked at a roadblock and transferred to Haaren again. Deppner ordered Van der Giessen and Van Rietschoten to be shot. On June 10th, they were executed by two members of the S.D. just outside the camp.

At the end of April 1944, the prisoners were transferred from the prison in Assen to Rawitsch (now Rawicz, Poland) prison in Upper-Silesia. Arie Mooy, Jacob Bakker, Humphrey Macaré, Felix Ortt, Frederik Rouwerd, Herman Parlevliet and Charles Pouwels were executed here on April 30th 1944. Early September 1944, most of the remaining prisoners, together with seven British commandos, were deported to Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. A few stayed behind in Rawitsch. Those deported to Mauthausen were allocated to the Kommando tasked with carrying the stones from the quarry. It soon became clear that it was not intended that the inmates should survive this work. In contrast to the other inmates, they were given no carrying slings so they had to carry the stones, weighing over 88 pounds with their bare hands. Whenever they put a foot wrong or dropped a stone, they were brutally tortured by the SS guards. Moreover they received nothing to eat. A few men were executed out of hand. At the end of the first day, 19 out of the original 47 had perished. The survivors were executed in the night of September 7th and their bodies were cremated. The cause of death was entered as: shot while trying to escape. It has remained unclear for a long time what had happened to the other prisoners and in some cases, it still guesswork. Jan Kist has very likely been executed in Rawitsch but the date is unclear. Ernst de Jonge died September 3rd, 1944 in Rawitsch. The official date and place of death of Herman Overes are unknown. He possibly died in Camp Gross-Rosen. Toon van Steen died December 31st, 1944 in Mauthausen.

Trix Terwindt was transferred to Ravensbrück in May 1944. Here she was housed in the Nacht und Nebel block. She weakened visibly. In February 194, she was deported to Mauthausen and at the end of April 1945, all female inmates were handed over to the Red Cross. Lauwers and Van der Reyden were transported from Haaren via camp Vught to Sachsenhausen concentration camp In September 1944. Later on, Lauwers was put on a transport to the satellite camp Rathenow where he was liberated by the Red Army on April 26th, 1945. Jordaan was transferred to the satellite camp Briesen and in February he was deported to Mauthausen. He would die there , at the age of 26, on May 3rd, 1945. Van der Reyden survived the war.

Victims

There still is discussion going on about the number of victims of the Englandspiel. Loe de Jong mentions 130 dead and over 200 imprisoned. The Germans themselves mentioned more than 400 arrests. Numerous resistance organizations were infiltrated as a result of the Spiel. They included Group Van Gruting/Anquin, Group Vorrink, Dienst-Wim, the sabotage group Pahud and others. During the Spiel, a total of 95 drops took place. As a result, 570 containers holding 33,000 pounds of explosives, 800 Stenguns, 60 Brenguns, 2,300 pistols, 50,000 rounds of ammunition, 8,000 hand grenades, 75 transmitters 450,000 guilders in cash fell in German hands.

Definitielijst

- Abteilung

- Usually part of a Regiment and consisting of several companies. The smallest unit that could operate independently and maintain itself. In theory an Abteilung comprised 500-1,000 men.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Englandspiel

- “England game”. The game, ironic as it may sound, of espionage and counter espionage between the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the Nazis. This “game” resulted in the death of approximately 54 allied spies.

- Mauthausen

- Place in Austria where the Nazi’s established a concentration camp from 1938 to 1945.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- SOE

- Special Operation Executive. British organisation during World War 2 conducting secret operations and espionage.

- Squadron

- A military unit in the Belgian navy usually six to eight small ships operating together under one command. The smallest military unit in the Dutch air force of about 350 men. In most countries is the designation of a military unit thesize of a company. It is either an independent unit, such as a battery, or part of a bigger Calvary unit. In the air force it is the designation of a unit of aircrafts.

Images

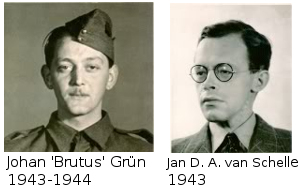

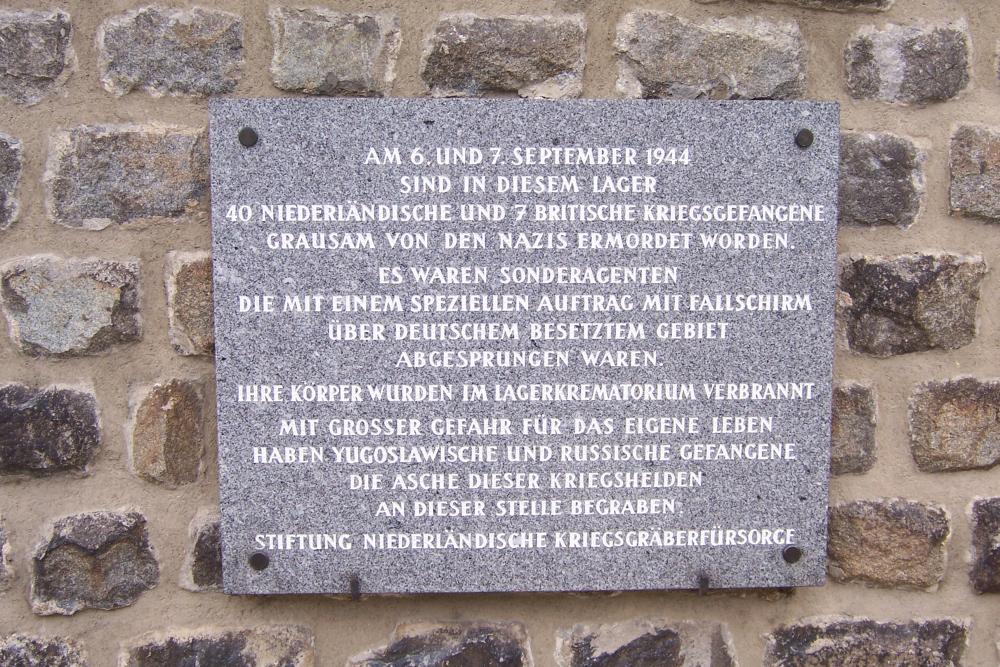

Memorial plate in the grounds of Concentration camp Mauthausen marking the spot where the ashes are buried of 40 Dutch and 7 British secret agents, mostly arrested during the Englandspiel and murdered in this camp on September 6th and 7th, 1944. Source: Traces of War.

Memorial plate in the grounds of Concentration camp Mauthausen marking the spot where the ashes are buried of 40 Dutch and 7 British secret agents, mostly arrested during the Englandspiel and murdered in this camp on September 6th and 7th, 1944. Source: Traces of War. On September 7th, 1965, a large number of relatives of Dutchmen, who had become victims of the Englandspiel flew to the former concentration camp Mauthausen to be present at the unveiling of a simple memorial in commemoration of these agents. Source: ANP PHOTO (1965)/Foto:Andre Van Der Heuvel.

On September 7th, 1965, a large number of relatives of Dutchmen, who had become victims of the Englandspiel flew to the former concentration camp Mauthausen to be present at the unveiling of a simple memorial in commemoration of these agents. Source: ANP PHOTO (1965)/Foto:Andre Van Der Heuvel. This plaque at Park Clingedael in The Hague commemorates the interrogation of the SOE-agent Jordaan and resistance fighter Boellaard, on 14 May 1942, by Heinrich Himmler. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

This plaque at Park Clingedael in The Hague commemorates the interrogation of the SOE-agent Jordaan and resistance fighter Boellaard, on 14 May 1942, by Heinrich Himmler. Source: Wikimedia Commons.Final considerations

British foul play theory

After the war, much research has been done into how it could have gone so terribly wrong in the Netherlands. None of the investigations unearthed any evidence of a conscientious action by the British. The theory, suggested by some, that the Englandspiel was a diversionary maneuver by the Allies for an invasion has little meaning. An Allied invasion on the Dutch coast has never been a realistic option and the Germans were aware of it as well. The routes of transport would have been too long and hence too vulnerable. Dutch beaches are too wide, providing the invasion force with too little cover. Moreover, the area behind the coast consisted mostly of polders intersected by narrow roads. In the event these polders would have been flooded, this terrain would have been perfect for defense and totally unsuitable for attack. As far as supply and air cover are concerned, it would be a risky enterprise as well. Moreover, the flat hinterland would be ideal for a German counter attack.

The idea, suggested by writer Pieter Hans Hoets, the Englandspiel was a conscientious attempt to divert the attention of the Germans to Calais and away from Normandy is not credible either. In 1942, a site for an invasion had not yet been chosen. That choice was made in 1943. Only then plans were drafted and put in motion for Operation Bodyguard, a massive effort to mislead the Germans as to the site of the invasion. The Englandspiel therefore cannot have been part of that because it been going on for a year. It is also doubtful that the Germans thought the invasion would take place in Calais because of the Englandspiel. It did dawn on them in 1943-1944 but only because of the cunning deception during Operation Bodyguard.

Another reason the advocates of a conspiracy gave for British intention was that the Allies wanted to spread the German forces of occupation as much as possible over the area occupied by the Axis powers or that they wanted to divert the German counter espionage from other areas. In the Netherlands, a relatively large force of occupation of some 100,000 strong was present. This mainly because the German military command considered the Netherlands a suitable area for German soldiers to rest and recuperate after having served on the eastern front. There is no indication whatsoever the Germans would have deployed a larger army of occupation in the Netherlands because of the Englandspiel. British historians also argue the British would never have sacrificed 12 aircraft and 83 men for such a double game. The S.O.E. was not authorized either to play such a game. That was left to the 20th Committee, subordinate to MI5, also in charge of Operation Double-Cross in which over 100 agents of the Abwehr were recruited as double agents in England. When the bubble of the Englandspiel finally burst, there was much consternation in London. Leendert Jonker, chairman of the parliamentary enquiry commission that investigated Dutch government policy during World War Two between 1947 and 1952 stated about the British foul play theory that he considered the thought these courageous men had been sent to their death intentionally, to be an horrendous accusation.

Even if one would presume, this was a conscientious action by the British secret services, what would be the use of continuing the action for so long and continue dropping so many men and supplies? This would have been to no advantage whatsoever to the British. Based on this hypothesis, the British would have known the Germans had arrested all agents, that they would not enlarge their force of occupation in the Netherlands any further or react in any other way. The danger to the Germans of an army of saboteurs would have evaporated in the mean time. The fact that the British continued sending agents can be better explained based on the theory that grave mistakes were made on the part of the British. S.O.E. Dutch Section firmly believed that all, or at least most of the agents, were operating in freedom and working hard to establish the army of saboteurs.

Writer Jo Wolters and other advocates of the British foul play theory argue that no one in England could foresee the fate the agents awaited and therefore they continued dropping them. This assumption is incorrect however: in accordance with the rules of warfare (e.g. the The Hague Convention of Land Warfare) spies and saboteurs can be executed. In his book "The secret war," Hastings wrote about this: "Each agent who was arrested faced death, legalized by the rules of war." In America and Great Britain for instance, a number of spies and saboteurs sent by the Germans, have actually been executed. Giskes and Schreieder attempted to prevent the execution of the arrested agents but it could have been known in advance, they would fail in this matter. It must be remembered that Giskes in his message to S.O.E. on April 1st, 1944, wanted to indicate the agents were still alive but was forbidden to do so by higher authorities. At the time (April 1944), the Abwehr had actually been dismantled, following the discharge of its chief, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris (Bio Canaris) in February of that year.

During and right after the war, many rumors circulated to the effect that the mission of the Dutch agents had been intentionally betrayed by someone. The Germans themselves hinted at this during the interrogation of the agents. The Dutch resistance accused François van ’t Sant of this for instance although there is no supporting evidence whatsoever. Sometimes the Germans dropped his name during an interrogation. Van ‘t Sant by the way had no occasion to commit treason as he did not have the necessary information at his disposal. In this connection, it must also be noted that it had been Van ‘t Sant as the first to warn that something was amiss in the Netherlands. From June 1942 onwards, he is said to have notified the Queen and Prime Minister Gerbrandy for instance that things were progressing all too easily in the Netherlands and that the British and Dutch secret services "collaborated" with the Germans. Little attention was paid to his warnings however. Bingham, Blizard’s successor as chief of S.O.E. Dutch was often accused of treason after the war. The man aroused suspicion because he had made a few weird statements. He had a bad reputation as he struggled with a drinking problem and because he was accused of having homosexual leanings. Bingham however cannot have betrayed the S.O.E. operation because at the time of the beginning of the Englandspiel, he was not even working for S.O.E. Dutch.