Youth and pre war career

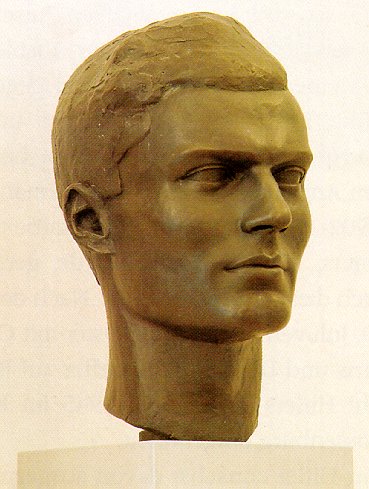

Claus Philipp Maria Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg was born November 15th 1907 in Jettingen, Bavaria, the youngest of three sons. His twin brother Konrad died one day after birth. The elder brothers Berthold and Alexander were twins as well. The Von Stauffenberg family stemmed from an aristocratic, 800 years old Schwabian lineage of prominent nobility. Claus’ father, Alfred Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg was a Major in the Cavalry, Commander in the Order of the Holy Joris and the last lord chamberlain of the King of Württemberg. Afterwards he became chairman of the revenue office until his retirement in 1928. Carolina, Gräfin Schenk von Stauffenberg had been lady in waiting of the Queen of Württemberg. Claus’ great-great-grandfather was the famous Generalfeldmarschall Von Gneisenau, one of the heroes of the time of Napoleon and co-founder of the Prussian General Staff. Claus was also a relative of Generalfeldmarschall Graf York von Wartenburg, a celebrity from the war against Napoleon as well.

In 1918, the Roman Catholic family moved to Lautlingen in the Schwabian Alps where they possessed an estate. Claus attended the Eberhard-Ludwigsschule in Stuttgart, a famous, 250 years old institution. He often suffered from headaches and inflammation of the throat and hence missed many lessons. During the last two years he stayed at the estate, receiving private education. His determination was enormous, however. He refused to accept his poor health. It seemed like he overcame his physical handicap by mental strength only. Claus even became a candidate for the German Olympic equestrian team.

Claus enjoyed the Lautlingen landscape. He and his brothers took long walks in the surroundings. He also retired frequently to meditate and enjoy the view of the hills and valleys. All three brothers took to poetry, philosophy, history, art and music enthusiastically. Claus played the cello and he dreamt about becoming a professional musician, composer or architect.

In addition, Claus developed a strong sense of his noble descent. To him aristocracy was a starting point and an essential part of his existence. In those times, nobility had the never ending duty to serve the community. They had gained their status not for nothing; they were responsible for those of another status and had to serve the community. Even the possession of a family estate was not a right to be taken for granted. It was a means to an end; the children could receive the upbringing and education they needed to bear responsibility. Claus understood this quickly and this attitude was to play an extremely important role in his later life.

In 1923, when Claus was 16 years of age, he met the poet Stefan George. This meeting and the relationship he established with George would have a profound influence on his development, his attitude and his norms and values. The Von Stauffenberg brothers joined the circle of George’s followers. The members of this group discussed politics, literature, philosophy, ethics and read and wrote poetry. The brothers’ mother paid a visit to George, who was being suspected of homosexuality, in order to find out what kind of relationships existed within the group but she returned a satisfied mother.

On March 5th, 1926, Claus passed his Arbitur (final examination). Meanwhile, he had given up his ideas of becoming a musician or an architect and he opted for a career in the army. This decision was a very unexpected one and it surprised everybody but Claus was self assured. He wanted to be involved with people, lead them and serve the community.

The Reichswehr, the German armed forces, had been starkly depleted as a result of the Treaty of Versailles. This meant more attention could be paid to training. Future officers had to serve as soldiers first. This was not always easy for the aristocratic Von Stauffenberg. On April 1st, 1926, he entered service in the Bavarian 17. Kavallerie-Regiment, the Bamberger Reiter. Von Stauffenberg rocketed through the ranks. After having passed his officers exams, he was promoted to Leutnant on New Year’s Day 1930 and to Oberleutnant on May 1st, 1933. He soon gained the respect and trust of his colleagues and superiors. He turned out to be a very capable and social officer but he sometimes forgot to shave and paid little attention to his hair and his uniform. He had a healthy contempt for protocol.

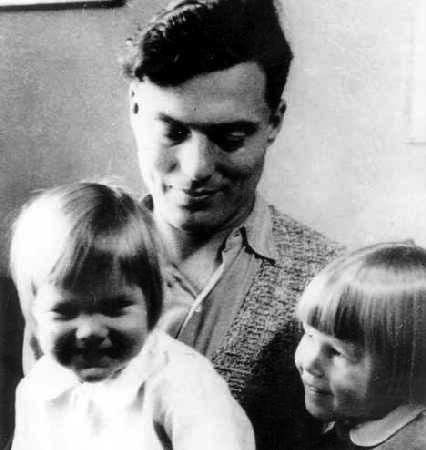

Meanwhile, on September 26th, 1933, handsome Von Stauffenberg had married Nina Freiin von Lerchenfeld, five years his junior, whom he had met in Bamberg. The couple was to have five children, three boys and two girls: Berthold (July 3rd, 1934), Heimeran (July 9th, 1936), Franz-Ludwig (May 4th, 1938), Valerie (November 15th, 1940) and Konstanze (January 27th, 1945). That year – 1933 – Von Stauffenberg also took an advanced course in horse riding. He mainly focused on dressage and won a competition against members of the German Olympic equestrian team that won the gold medal at the 1936 summer games.

Von Stauffenberg did not only focus on his military career. He spoke Russian and English fluently and he also mastered French, Greek and Latin. Meanwhile he continued attending the poetry nights with Stefan George. Among other things they discussed the rise of National socialism. To George, it was already clear how dangerous Hitler (Bio Hitler) was and Von Stauffenberg also began to doubt him. Von Stauffenberg had never been an advocate of the Nazi regime although he did agree with some points of the political program of the National socialists, such as ignoring the Treaty of Versailles and the expansion of the army. In particular the Kristallnacht of 1938 made his disdain for Hitler increase drastically.

Old Reichspräsident Von Hindenburg died on August 2nd, 1934. His presidential duties were taken over by the Kanzler, Adolf Hitler who officially became Reichskanzler and Führer from that moment on. In that capacity he also stood also at the head of the armed forces. That very same day, all German soldiers were obliged to pledge a personal oath of allegiance to Hitler. Von Stauffenberg considered this oath of little importance and reacted laconically. Yet this oath was to pose a perennial obstacle to the establishment of a wide spread resistance within the army. Many men felt like a double traitor, to the chosen leader of the fatherland as well as to Hitler. Those who did join the resistance did so because they were convinced of Hitler’s illegal seizure of power being a more serious act of treason than bringing down the Führer.

In October 1936, Von Stauffenberg took up studies at the Kriegsakademie, along with other promising young officers which could earn him a position on the General Staff. On New Year’s Day 1937, he was promoted to Rittmeister. In 1938, Von Stauffenberg completed his studies. August 1st, 1938 saw him promoted to Quartermaster (Ib) of the Leichte Division. This division invaded Czechoslovakia in 1938. In order to help the population in the occupied country, Von Stauffenberg set up an aid program. He organized transports of foodstuffs and had fuel and raw material delivered from Germany.

Definitielijst

- Cavalry

- Originally the designation for mounted troops. During World War 2 the term was used for armoured units. Main tasks are reconnaissance, attack and support of infantry.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- National socialism

- A political ideology drawn up by Hitler based on the superiority of the German race, the leader principle and fierce nationalism that was fed by the hard Peace of Versailles. National socialism was anti-democratic and racist. The doctrine was elaborated in Mein Kampf and organised in the NSDAP. From 1933 to 1945 National socialism was the basis of totalitarian Germany.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- Reichswehr

- German army during the Weimar republic.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- socialism

- Political ideology aiming at slight or no class differences. Means of production are owned by the state. Evolved as a response to capitalism. Karl Marx tried to substantiate socialism scientific.

Images

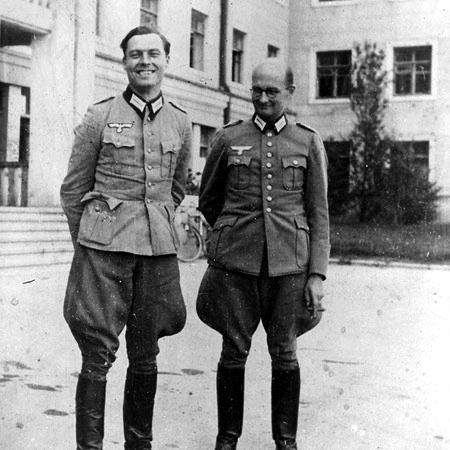

The General Staff and Africa

In September 1939, Von Stauffenbeg’s division was part of the armed force that invaded Poland. Here he saw the Einsatzkommandos at work, the fast moving death squads of the SS. Indiscriminate murders were committed among the civilians to the great disgust of Von Stauffenberg. This caused him to loathe the SS, something he did not exactly hide. Following the Polish campaign, he was promoted to Hauptmann on November 1st and the division was renamed the 6. Panzerdivision. The unit invaded France in the spring of 1940.

On May 31st, an important transfer followed for Von Stauffenberg: he was given a position within the Organisationsabteilung (organization department) of the General Staff of the O.K.H. (Oberkommando des Heeres, supreme command of the army). Initially this seemed like bad news for Von Stauffenberg as he felt more at home on the battlefield but he soon realized he was in the right position within the General Staff. On January 1st, 1941, Von Stauffenberg was promoted to Major. He was closely involved in the preparations for Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union. Initially, this operation proceeded successfully but soon, Von Stauffenberg’s department was flooded with requests for reinforments. In his position, he also gained an inside view of the shocking waste of German manpower. He traveled along the front to discuss the problems, also talking to Henning von Treschkov and his adjutant Fabian von Schlabrendorff, two men who also opposed the regime.

Von Stauffenberg’s attitude was still considered very friendly and social by his superiors. With his spontaneous and infectious smile, he often acted as mediator to play down arguments. His razor sharp sarcasm and his dominant attitude were mentioned as his negative points. Biographer Joachim Kramantz wrote about this:

- As young as he was, Stauffenberg was soon trusted by everybody. People who made his acquaintance flocked to him to pour out their hearts and that did not only apply to colleagues his own age and rank. Even generals visiting headquarters from the front or from the reserve troops often took the opportunity to speak to him. Whenever Stauffenberg was late for lunch, everyone yelled: "There is crying general sitting in his office again." All sorts of cases were brought before him that did not really belong to his sphere of work. He could not care less whether he ignored an order from Hitler in doing so. He busied himself with everything he was interested in, even though it was outside his official competence.

In July 1942, Hitler paid a visit to O.K.H. headquarters in Vinnitsa. On that occasion, Von Stauffenberg met Hitler for the first time. What exactly happened is unknown but at the end of Hitler’s visit, Von Stauffenberg’s disgust of the man was even greater, "Isn’t there a single officer around at headquarters," he roared "who is capable to point his gun at that monster?"

Von Stauffenberg was personally in charge of filling the ever growing gaps in the German ranks. Soldiers of the Red Army offered an attractive solution: he managed to save a large number of Soviet prisoners of war from the hands of the SS by incorporating them in the Wehrmacht. When Hitler prohibited the recruitment of Soviet military, Von Stauffenberg managed to publicize this order as long as three weeks before it became effective and as a result, many Soviets could still be incorporated in the meantime. Recruiting non-Soviet troops was permitted though. Hans von Herwarth wrote about this:

- The SS had found out that the Cossacks were an independent people. Based on this, Von Stauffenberg decided Hitler’s prohibition order did not apply to them. From our side, we made this exceptional position widely known. Thousands of prisoners – including many Russians – took the hint, claimed they were Cossacks and in so doing managed to get out of the camps.

In September 1942, the Chief of the General Staff of the O.K.H., Generaloberst Franz Halder, a close friend of Von Stauffenberg, was succeeded by General der Infanterie Kurt Zeitzler. Von Stauffenberg did not think much of him but Zeitzler highly respected Von Stauffenberg and considered him ‘a good future corps and army commander’. Such promising officers were rare and therefore, Von Stauffenberg was promoted to Oberleutnant on January 1st, 1943. Shortly after, without consulting Van Stauffenberg himself, he was transferred to the post of chief of operations (Ia) of the 10. Panzerkorps in North-Africa. Zeitzler officially declared: "I wanted him to gain experience as a staff officer and troop commander in order to prepare him for his future task as commander of a corps and an army" The decision for his transfer was also made based on the wish to get the outspoken and explicit officer away from the eastern front where he caused increasing unrest. The supreme command wanted to save him from the claws of the SS and SD. Von Stauffenberg regretted the necessity but he told his new divisional commander that the German soil was gradually becoming too hot for him.

On February 15th, Von Stauffenberg, full of energy, officially embarked on his task in the Afrikakorps. At that moment, the 10. Panzerdivision was in combat near Sidi-Bourzid and the Casserine Pass where the freshly arrived American 2nd Corps got their baptism of fire. For the Americans, the operation ended in disaster but after Major-general George Patton had assumed command, the Germans were driven back.

On April 7th, the same day British-American troops from the west made contact with General Montgomery’s 8th Army (Bio Montgomery), Von Stauffenberg assisted in the organization of the German withdrawal to the Tunisian coastal town of Sfax. His staff car zigzagged through a long line of trucks and soldiers when the column was attacked by a number of American P-40 fighter bombers. Numerous vehicles and soldiers were hit. As his driver wound his way through the wreckage, Von Stauffenberg stood upright in his car, giving directions when he was targeted by the .50 machineguns of the P-40s. His hands raised above his head, he jumped out of the car but at that moment he was hit by the bullets. He was found later on, semi conscious, lying beside his overturned and burnt out car. He was gravely injured: both eyes were damaged by bullets and his right arm was all but shot away, just as two fingers of his left hand. One of his knees was hit and shrapnel lodged in his back and in his legs. He was rushed to the nearest field hospital in Sfax were he was immediately operated upon. The remains of his right hand were amputated just below his wrist, as well as his left ring finger and little finger. His left eye was also removed.

As Montgomery was approaching Sfax, Von Stauffenberg was transferred to the hospital in Cartago. En route, the ambulance frequently came under fire from Allied aircraft. The physicians feared the worst and Von Stauffenberg was flown to Munich. He was running a high fever, his entire body was bandaged and his chances of survival appeared slim. While in hospital, the Oberleutnant was being visited by many high ranking officers, including Zeitzler. Many family members came by as well, such as his wife, his mother and his uncle Nikolaus Graf von Üxküll-Gyllenband. Von Stauffenberg talked to him about his growing awareness he had been spared to fulfill a certain task in his life. Because of this mission, his will power to recuperate was extremely strong. He was discharged from hospital as early as July 3rd.

Von Stauffenberg regained the sight in his right eye and he taught himself to write again with his three remaining fingers, albeit arduously. From then on he wore a black patch over his left eye but later on, he had an artificial eye made. He also had deep scars in his face and his hearing was impaired. Despite his handicaps, Von Stauffenberg did not consider himself disabled. After a bit of practice, he managed to dress himself again with his three fingers and his teeth only. He could hardly recall what he had done with all of those ten fingers when he still had them, he remarked jokingly.

Definitielijst

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Out of hospital and in the resistance

Despite his severe mutilations, Von Stauffenberg remained in the army. On November 1st, 1943, he accepted the position of chief of staff at the Allgemeines Heeresamt (general office of the armed forces), part of the Ersatzheer (reserve army). The Ersatzheer had its headquarters in the Department of War on the Bendlerstrasse in Berlin. Stauffenberg’s chief was General der Infanterie Friedrich Olbricht, a member of the resistance. From here, Von Stauffenberg kept in touch with Von Treschkov (Bio Von Tresckow) and other members of the resistance. The latter came up with the plan to use the Ersatzheer as a nucleus for a coup.

Various attempts at killing Hitler had already failed. Von Stauffenberg, meanwhile considered the heart and soul of the resistance, thought about making an attempt himself. His co-conspirators could not do without him though: the determined and energetic Von Stauffenberg was the most suitable man to lead the coup. He kept the group together and continued motivating the other members.

April 1st, 1944 saw Von Stauffenberg promoted to Oberst and on June 20th he was given the important function of chief of staff of the Ersatzheer. This function enabled him to get close to the Führer for he was frequently called to headquarters to report on the situation of the Ersatzheer. It gradually became obvious that no attempt would be made if Von Stauffenberg would not carry it out himself. Among the members of the resistance, he was the only one capable of getting close enough to Hitler so it was decided, more or less by force, to have Von Stauffenberg make the attempt. It was like a commander carrying out his own orders. Von Stauffenberg was to take the bomb to Hitler’s headquarters and then return to Berlin as soon as possible to take charge of the coup.

On July 11th, Von Stauffenberg went to Adolf Hitler’s headquarters in Berchtesgaden as representative of the Ersatzheer. This time he carried a bomb but although he was with Hitler and Hermann Göring (Bio Göring) for half an hour, he did not carry out the attempt. It turned out Heinrich Himmler (Bio Himmler) was absent and the conspirators wished in any case to kill both Hitler and Himmler. On July 15th, he had another opportunity but this time, both Himmler and Göring were absent.

The conspirators now agreed Von Stauffenberg would make his move on July 20th when he was at Hitler’s new headquarters, the Wolfsschanze (wolves’ lair) in Rastenburg, whether Himmler and Göring were present or not. The resistance was in danger of being exposed soon: some members of the civilian resistance had been arrested including Adolf Reichwein and Julius Leber. Quick action was imperative. A friend of Von Stauffenberg also told him about rumors, circulating in Berlin, to the effect that the Führer’s headquarters could be blown up any moment. "Then we have no choice anymore," Von Stauffenberg responded. "The Rubicon has been crossed."

In the early evening of July 19th, Von Stauffenberg halted near a small church in Berlin-Dahlem, a suburb of Berlin, where a service was going on. He stood in the back, alone, for a long time and afterwards let himself be driven home. He had a lengthy conversation with Adam von Trott zu Stolz, member of the civilian resistance. He spent the rest of the evening with his brother Berthold who was also involved in the plot (See for the sequence of events: Assault 20-07-1944).

At 07:00 hours in the morning of July 20th, Von Stauffenberg and his adjutant, Oberleutnant Werner von Haeften boarded a plane to Rastenburg. From the airfield they drove to the Wolfsschanze by car. The meeting was to begin at 12:30. As it was very warm, Von Stauffenberg went to a bathroom, supposedly to put on a clean shirt but in reality he activated the detonator of the bomb. He placed his briefcase containing the bomb in the chart room and then left, allegedly to make a phone call. After a few minutes the bomb exploded and Van Stauffenberg and his adjutant left for Berlin. Erich Fellgiebel however, who was to pass the code word to Berlin when the attempt had succeeded, saw to his alarm Hitler coming out. An officer had shoved the briefcase with the bomb behind a massive leg of the table that had muffled the explosion.

After a few hours, Von Stauffenberg and his adjutant arrived in Berlin. Olbricht and Oberst Albrecht Ritter Merz von Quirnheim had their doubts however and no precise orders had been issued. After hesitating for a long time, Olbricht finally issued new orders but by then it was much too late. Discussion was also going on with the supreme commander of the Ersatzheer, Friedrich Fromm, who did not support the coup and was furious. He had heard from Wilhelm Keitel that Hitler was still alive. The conspirators began having a scary premonition but nonetheless they placed Fromm under arrest and got to work, directed by Von Stauffenberg.

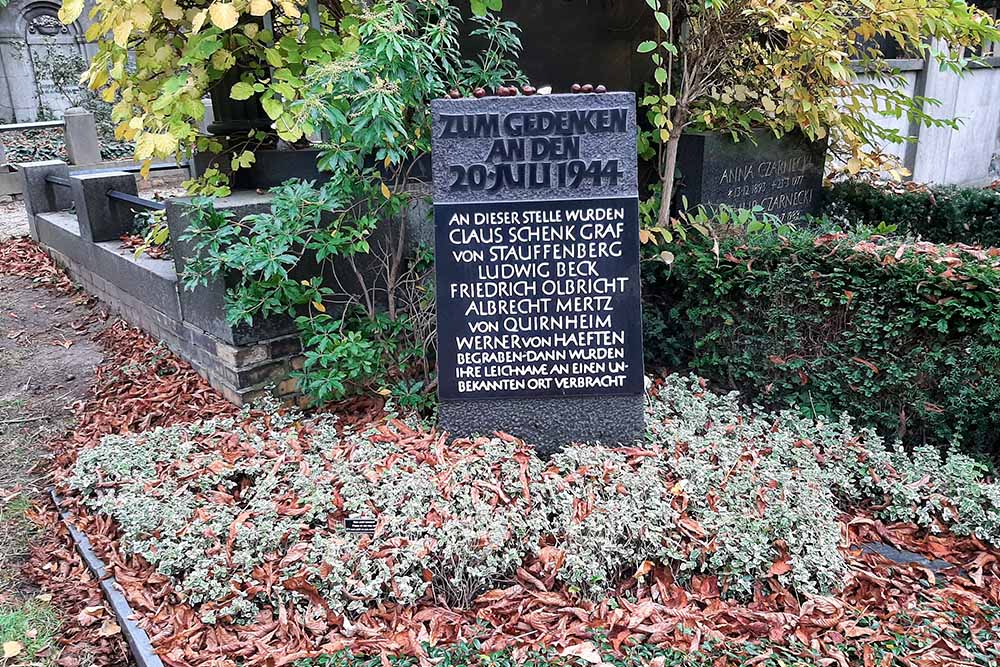

The indecisiveness had been fatal, though. Just before 18:00 hours, the first orders were issued by the Führer’s headquarters, contradicting those of the conspirators. In Berlin, troops were mobilized and a number of officers in the Ministry of War, who had remained loyal to Hitler, took up arms. They freed Fromm and the conspirators gave up after a short fire fight. A number of men were arrested. Generaloberst Ludwig Beck committed suicide and the four major conspirators were sentenced to death.

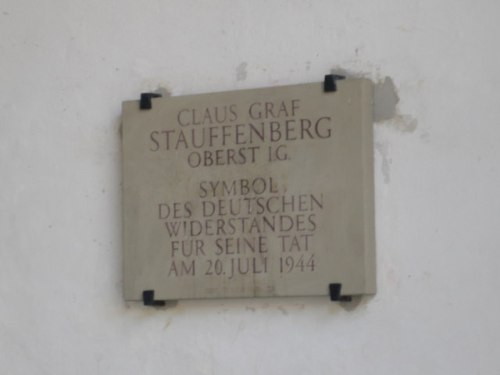

At 00:15 in the morning of July 21st, Von Stauffenberg, Olbricht, Von Haeften and Merz von Quirnheim were placed in front of a heap of sand in the courtyard of the Ministry of War. Illuminated by the headlights of a car, they were to be executed by a 10-man firing squad in sequence of their rank. When the squad took aim to execute Von Stauffenberg, Von Haeften threw himself in front of him to catch the bullets. The squad took aim once more and in the split second before he was mortally hit, he shouted something at his executioners. Due to the echoing noise, his words were hard to understand. According to some, he yelled: "Es lebe unser Heiliges Deutschland" (Long live our Holy Germany). According to others – and that seems more plausible – with his last words, Von Stauffenberg’s referred to his great mentor, the poet Stefan George and the title of the latter’s poem on German resistance: "Es lebe unser geheimes Deutschland" (Long live our secret Germany). Subsequently, the bodies were buried in the old St. Mattheus cemetery in Berlin, dressed in their uniforms with all their decorations. The next day though, Himmler ordered the bodies to be exhumed and cremated. The ashes were dispersed.

Read more about the decorations of this person on WW2Awards.com

Definitielijst

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Wolfsschanze

- Headquarters of Adolf Hitler in East Prussia.

Images

Supplement

Promotions:

18-08-1927: Fahnenjunker-Gefreiter15-10-1927: Fahnenjunker-Unteroffizier

01-08-1928: Fähnrich

01-08-1929: Oberfähnrich

01-01-1930: Leutnant

01-05-1933: Oberleutnant

01-01-1937: Rittmeister

01-11-1939: Hauptmann i. G.

01-01-1941: Major i. G.

01-01-1943: Oberstleutnant i. G.

01-04-1944: Oberst i. G.

Positions:

01-04-1926: Service in Reiterregiment 17 in Bamberg17-10-1927: Infanterieschule Dresden

01-10-1928: Kavallerieschule Hannover

30-07-1930: Pionier-Lehrgang

18-11-1930: Mörser-Lehrgang

01-10-1934: Adjutant Kavallerieschule Hannover

06-10-1936: Kriegsakademie Berlin-Moabit

01-08-1938: Ib 1. Leichte Division

18-10-1939: Ib 6. Panzerdivision

31-05-1940: Hoofd Gruppe II, Organisationsabteilung OKH

15-02-1943: Ia 10. Panzerdivision

01-11-1943: Chef des Stabes Allgemeine Heeresamt

20-06-1944: Chef des Generalstabes Ersatzheer

21-07-1944: Executed

04-08-1944: Discharged from the Wehrmacht

Awards:

??-??-1928: Sportabzeichen in Bronze17-08-1929: Ehrendegen

02-10-1936: Wehrmacht-Dienstauszeichnung IV. Klasse

01-04-1938: Wehrmacht-Dienstauszeichnung III. Klasse

??-??-????: 1939 Eisernes Kreuz II. Klasse

31-05-1940: 1939 Eisernes Kreuz I. Klasse

25-10-1941: Königlich Bulgarischen Tapferkeitsorden IV. Klasse, I. Stufe

11-12-1942: Finnisches Freiheitskreuz

14-04-1943: Verwundetenabzeichen in Gold

20-04-1943: Deutsch-Italiänische Erinnerungsmedaille

08-05-1943: Deutsches Kreuz in Gold

Definitielijst

- Eisernes Kreuz

- Iron Cross. German military decoration.

- OKH

- “Oberkommando des Heeres”. German supreme command of the army.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Claus met twee van zijn kinderen Source: http://www.temakel.com.

Claus met twee van zijn kinderen Source: http://www.temakel.com.Information

- Article by:

- Auke de Vlieger

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- BAIGENT, M. & LEIGH, R., Claus von Stauffenberg, B.V. Uitgeversmaatschappij Tirion, Baarn, 1994.

- BERBEN, P., De aanslag op Hitler, Nederland's Boekhuis N.V., Tilburg, 1963.

- GRABER, G., Von Stauffenberg, Standaard Uitgeverij, Antwerpen, 1994.

- HOFFMANN, P., Stauffenberg, University Press, Cambridge, 1997.

- KRAMARZ, J., Stauffenberg, Bernard & Graefe Verlag fur Wehrwesen, Frankfurt am Main, 1967.

- MANVELL, R., De aanslag op Hitler, Standaard Uitgeverij, Antwerpen, 1989.