Introduction

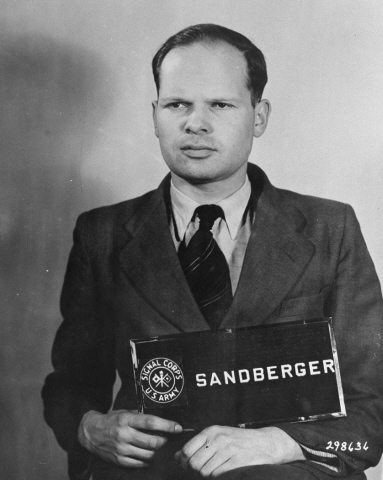

While the attention of the international media was focused on the trial against camp guard Ivan Demjanjuk in May 2010, another Nazi war criminal died that year who had been living a comfortable life for decades. He had never gone into hiding in South-America, was not registered on any wanted list, even that of Simon Wiesenthal and could easily be found in the telephone directory. He sure had been sentenced, even to death. His death sentence, imposed on him in April 1948 may have been changed to life imprisonment but his release followed as soon as seven years later.

His name was Martin Sandberger, former SS-Standartenführer. As commander of Sonderkommando 1a, later renamed Einsatzkommando 1a of Einsatzgruppe A and chief of the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) and Sicherheitspoolizei (SIPO) in Estonia, he was responsible for the execution of hundreds of Communists and Jews in this Baltic state. Benjamin Ferencz, the American chief prosecutor during the Einsatzgruppen trial in Nuremberg, called him "an active and probably even an industrious member of the gang of murderers that killed hundreds of thousands of innocent people." In his opinion, the death penalty was well earned in his case. (See Einsatzgruppen Art.)

Historians, including German Michael Wildt in his standard work "Generation des Unbedingten"(generation of the unsure) have shown that Sandberger was a fanatic Nazi. That was already so during his years as a student when he was active in the Nationalsoziallistische Studentenbund, making a considerable contribution to the Nazification of Tübingen University. Even during his study of law, he was recruited by the SD (Sicherheitsdienst, security service) of the intelligence service of the SS. A career within the R.S.H.A. (Reichssicherheitshauptamt, head office of state security) was on the horizon of this young and gifted lawyer.

As an employee of the R.S.H.A., Sandberger was not just a man in the wrong place at the wrong time, which might more or less apply to Demjanjuk. As for the Ukrainian however, his participation in the Holocaust was a way out of the starvation and misery in the prisoner of war camp where he was. But Sandberger and his fellow officers in the Einsatzgruppen "were no small cogs in an anonymous machinery of destruction" as Michael Wildt states: "on the contrary, they were the men who drafted the blueprints, built and operated the machinery that made murder of millions of people possible."

How could Martin Sandberger, according to Canadian historian Hilary Earl: "an ideological soldier of the Third Reich", escape the death penalty, enjoy accelerated release and could live undisturbed in Germany for decades? This article attempts to provide an answer to this question. A biography of the man who was one of the few managerial Holocaust perpetrators still alive until his demise in Stuttgart on March 30th, 2010.

Definitielijst

- Einsatzgruppen

- "Taskforces of Deployment Squads". Special units composed of various SS and police services under supervision of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA). Einsatzgruppen were deployed during the invasion of Poland in 1939 and during operation Barbarossa in 1941. In 1939 these units were ordered to eliminate the Polish intelligentsia. In the Soviet Union they were deployed to execute various political and racial enemies of the Third Reich, like Jews, gypsies and communists. The "Holocaust by bullets" in the Soviet Union was the horrendous first act of the eventual "final solution".

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Sicherheitsdienst (SD)

- The national socialistic intelligence and counterespionage service of the SS.

- SIPO

- ”Sicherheitspolizei”. Combination (since 1936) of the Gestapo and criminal police.

Images

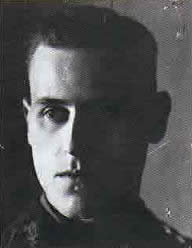

Youth and period of study

Martin Sandberger was born July 17th, 1911 in Berlin Charlottenburg, the son of a manager in the chemical concern IG-Farben. The origins of his family lay in Württemberg in southwestern Germany. His forebears from his father’s lineage included clergymen, lawyers and foresters and from his mother’s lineage teachers and leather workers. Sandberger was raised in Protestant fashion and after Volksschule, he attended the Realgymnasium in Höchst near Frankfurt. After graduation in March 1929, he studied law and political sciences at the universities of Munich, Cologne, Freiburg and ultimately Tübingen. As a student he was drawn to National socialism and at the age of 20 he became a member of the Nationalsozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund (NSDStB or Nazi Student Union) at the end of 1931, the N.S.D.A.P. and the Sturmabteilung (SA). During 1933 and 1934 he was in command of a Sturm (company) and a Sturmbann (battalion) in the SA.

The foundation of his Nazi career was laid at Tübingen University. From July 1932 to July 1933 he was Studentenschaftsführer (student leader) on behalf of the NSDStB and from May to July 1933 Hochschulgruppenführer (university group leader). At university, Sandberger was part of a group of fanatic young Nazis. His fellow students and political comrades Erich Ehrlicher and Erwinn Weinmann were to hold executive functions during the war, just like him, as commander of Sonderkommando 1b and Sonderkommando 4a respectively. After Hitler had seized power in 1933, Sandberger and the other Nazi students dedicated themselves to the Gleichschaltung (equalization) of the university. According to Michael Wildt, in the spring of 1933, Sandberger and Ehrlicher were not only Nazi activists wanting to establish and expand the political power of their own party but revolutionaries who saw the possibilities to grab power and use it in the struggle against institutional rules to their own advantage by exerting political pressure from below.

Early February 1933 the students council demanded the departure of a Jewish employee of the university on orders from the NDStB. The same month, Sandberger managed to persuade the principal to end the semester a few days earlier because of the elections for the Reichstag on March 5th. After the electoral victory of the N.S.D.A.P. Ehrlinger and Sandberger hoisted the swastika flag on the university building. The principal had the flag removed that same night but on March 9th, he grudgingly tolerated the flag to be hoisted, just like on other public buildings during a parade of members of the SA, SS, Stahlhelm and Hitler Youth. Michael Wildt called the incident a symbolic struggle by Sandberger and his followers in the fight for control of the university. It was just the beginning of the gradual Nazification of Tübingen university, a process Sandberger would put a great stamp on after his appointment as leader of the students’ union in Tübingen.

Sandberger’s first official act as leader of the students union was the abolishment of the student groups of each separate faculty and the appointment of new student representatives. It goes without saying that his newly appointed representatives were political adherents. The students union in Tübingen, reorganized in this way, stood at the base of the equalization of the university. Undesired lectors were attacked and boycotted. Early July 1933, at a meeting attended by Sandberger, the decision was made that the students union from now on had a say in the institution of faculties, questions concerning the curriculum and the appointment of lectors. Michael Wildt concludes: "Sandberger and Ehrlicher used the weakness and the insecurity of the leadership of the university to shift the constellation of power to the advantage of the revolutionary students and to carry through their demands for the removal of unwanted lectors." The principal attempted in vain to curb the influence of National socialism on his university until December 11th, 1933 when the Württemberg Minister of Culture replaced him with a Nazi successor. It was the umpteenth victory of Sandberger and his fellow Nazi followers over the leadership of the university.

His busy political career had no influence on his records because in May 1933, Sandberger passed his first judicial state examination with the mark ‘commendable’ which was very unusual for a law student. In November of that same year, he was promoted to Doctor at Law with the extremely rare mark ‘very good’. In his thesis, entitled: "Die Sozialversicherung im nationalsozialistischen Staat: Grundsätzliches zur Streitfrage: Versicherung oder Versorgung?", (social security in the Nazi state: basics of the argument: insurance or care) he praised the system of social security in Nazi Germany. After graduation, he did not give up politics though. In the fall of 1933, he was briefly active in the national leadership of the NDStB in Berlin. In 1934 and 1935, he held several functions in the SA. In the spring of 1934, he served as Zugführer (platoon leader) on an SA sports academy. In the summer he was briefly active in the Reichs-SA-Hochschulamt, the department within the national leadership of the SA responsible for university education. From mid September 1934 until mid March 1935 he was employed as chief of the educational department of the SA.

Definitielijst

- Gleichschaltung

- “Standardisation”, “equalisation”. Aim of the NSDAP to model all social and cultural organisations to the national socialist ideal. Nobility and other traditional structures were targeted, as were other pluralist phenomena.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- National socialism

- A political ideology drawn up by Hitler based on the superiority of the German race, the leader principle and fierce nationalism that was fed by the hard Peace of Versailles. National socialism was anti-democratic and racist. The doctrine was elaborated in Mein Kampf and organised in the NSDAP. From 1933 to 1945 National socialism was the basis of totalitarian Germany.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- socialism

- Political ideology aiming at slight or no class differences. Means of production are owned by the state. Evolved as a response to capitalism. Karl Marx tried to substantiate socialism scientific.

- Sturmabteilung

- Storm detachment. Semi-military section of the NSDAP. Founded in 1922 to secure meetings and leaders of the NSDAP. Their increasing power was stopped during “The night of the long knives”, 29 and 30 June 1934.

- swastika

- Equilateral cross, symbol of Nazi-Germany.

Images

Career in the SD

At the end of the summer of 1934 when the top of the SA was liquidated by the Nazi leadership in the Night of the Long Knives, the future of a young lawyer like Sandberger lay no longer with the SA. It was in the SS where gifted Nazis like him could make a career for themselves. Sandberger had met Reichsstudentenführer Gustav Scheel in Berlin who had been appointed chief of the SD-Oberabschnitt Südwest (branch of the SD) in Stuttgart in July 1935. After Scheel had introduced him to the SD, Sandberger promised to cooperate. No paid job for the time being but as a volunteer he was closely involved in the intelligence service. In March 1935, he left Berlin to gain practical experience, required for his study, during his Refendariat (stage). Carlo Schmidt, his mentor was to play an important role in his post war life. Sandberger was accepted as assistant to the Faculty of Law at Stuttgart University. In July 1935, he attended a course at the SD Schule Bernau in Berlin.

Scheel, chief of SD-Oberabschnitt Südwest, employed Sandberger at the main office as chief of Amt II 2 Lebensgebiete (Living areas) as of January 1st, 1936 and as Untersuchungsführer (chief of investigation). Scheel’s SD region was an important recruitment pool for the SD leadership in the future Reichssicherheitshauptamt (R.S.H.A.). Erich Ehrlinger and Erwin Weinmann, Sandberger’s fellow students in Tübingen, also started their SD career here. Sandberger was not a full time employee however because in November 1936, he passed his second state examination in law and was subsequently employed in the offices of the Landrat (Regional council) of Stuttgart, Esslingen and Waiblingen. Since his employment in the SD he also was a member of the SS, holding the rank of SS-Untersturmführer. In Sandberger’s recommendation prior to his promotion to SS-Obersturmführer, Scheel highly praised his subordinate. In Scheel’s words, he was "one of the most capable and best men of the SD-OA Südwest. He is determined, bright, quick and with a sound judgment. Highly gifted, industrious and not shy. He possesses a sharp logic and is available for anything. He passed his lawyer’s exams with one of the best marks in Württemberg".

Despite his tender age, Sandberg’s star was rising within the SD. He exchanged letters with Hans Frank (Bio Frank), the incumbent president of the academy of German law and later governor of the Generalgovernment in occupied Poland. When Sandberger was promoted to SS-Sturmbannführer in 1938, Scheel praised his pupil again: "Dr. Sandberger is conspicuous by his achievements and is appreciated by everyone," he wrote. He emphasized Sandberger was also highly regarded by the higher echelons of the Nazi leadership, naming Secretary of State of Internal Affairs Wilhelm Stuckart as an example.

A good position was certain to come forth and in October 1939, Sandberger was called to Berlin where he was appointed, by SD chief Reinhard Heydrich (Bio Heydrich) personally, chief of the recently established Einwanderzentrale Nord-Ost (E.W.Z. or Immigration office northeast) in Gotenhafen (today Gdynia in Poland). Germany meanwhile had invaded Poland and the inhabitants of the port of Gotenhafen were to be deported to the Generalgovernment in order to create room for ethnic German emigrants, so called Volksdeutsche, from the Baltic states and the Soviet Union. In Berlin, Sandberger was given instructions by Heydrich personally. Sandberger’s E.W.Z. was to supervise the naturalization and temporary housing of the Volksdeutsche. When the first transports were already under way, Sandberger and his team left for Gotenhafen on October 10th, 1939.

Definitielijst

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Night of the Long Knives

- Night of 30 June to 1 July 1933 during which Hitler killed many of the demanding leaders of the SA, including Ernst Röhm.

- Oberabschnitt

- Main district of the protection squadron (Schutzstaffel), the SS, from November 1933.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Images

Appointed commander of Sonderkommando 1a

In the beginning of the war, Sandberger was also responsible for the German resettlement policy elsewhere, apart from Gotenhafen. Early 1940, 160 Jews from the district of Scheidemühl in western Prussia (today Pila in northwestern Poland) were deported to Lublin in mid January on Sandberger’s urging, so Baltic Germans could settle in Schneidemühl. In May 1940, Sandberger was transferred to the Alsace in France, along with his mentor Gustav Adolf Scheel who had been named local commander of the SD and SIPO and who had selected Sandberger as his right hand man.

At the end of April 1941, SS leader Heinrich Himmler (Bio Himmler) ordered Sandberger to occupy himself with coordinating the removal of Slovenians from the Untersteiermark in northeastern Slovenia. That summer however, his career took a different turn as he was appointed commander of Sonderkommando 1a of Einsatzgruppe A. These were special units of the R.S.H.A. that were charged with securing the areas behind the front following the German invasion of the Soviet Union; which in practice boiled down to executing Communist party officials, partisans and other suspected hostile elements. The main target however were the Soviet Jews, initially adult males only but later on women and children as well. The mass murder of Jews therefore did not begin in the extermination camps but with mass executions by the Einsatzgruppen on the eastern front. (See also: Einstazgruppen Art.)

As Sandberger has said himself, as early as the spring of 1941 he was informed about the imminent attack on the Soviet Union by SS-Brigadeführer Bruno Streckenbach who was, in his capacity of chief of Amt 1 of the R.S.H.A., responsible for recruiting and training of the men of the Einsatzgruppen. Some two weeks prior to Operation Barbarossa, Sandberger left for Pretzsch in what is today the federal state of Sachsen-Anhalt. The members of the Einsatzgruppen were being prepared for their task at the local border police academy. Many of those who had been there, including Sandberger, declared after the war they had been informed in Pretzsch about Hitler’s (Bio Hitler) order to kill all Jews in the Soviet Union. Many historians doubt however if such an order had already been given at the time. They conclude that Sandberger and his colleagues, in order to help their defense, were hiding behind this order to deny their own responsibility.

Tactically speaking, each of the four Einsatzgruppen were elements of the various armies of invasion each with their own theatre of operation. For Einsatzgruppe A, Einsatzkommando 1a was part of, that was Heeresgruppe Nord; its theatre of operation stretching from the Baltic states and Byelorussia to Leningrad. The commander of Einsatzgruppe 1a, Sandberger’s superior, was SS-Brigadeführer Franz Walter Stahlecker, also a lawyer educated in Tübingen. Sandberger’s Sonderkommando formed part of 18. Armee of Heeresgruppe Nord which was active between the Riga Bend and Lake Peipus on the border between Estonia and Russia. He commanded 105 men from the various departments of the R.S.H.A., including 18 men from the Gestapo, 11 from the Kriminalpolizei (criminal police) and eight from the SD. Estonia was to be the main area of operation of Sonderkommando 1a and from December 3rd, 1941 onwards, Sandberger would be chief of the SIPO and SD as well. During the interbellum, the country had been independent but it was occupied by the Soviet Union since August 1940. Prior to World War Two, 4,500 Jews out of a population of one million were living in Estonia.

Definitielijst

- Einsatzgruppen

- "Taskforces of Deployment Squads". Special units composed of various SS and police services under supervision of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA). Einsatzgruppen were deployed during the invasion of Poland in 1939 and during operation Barbarossa in 1941. In 1939 these units were ordered to eliminate the Polish intelligentsia. In the Soviet Union they were deployed to execute various political and racial enemies of the Third Reich, like Jews, gypsies and communists. The "Holocaust by bullets" in the Soviet Union was the horrendous first act of the eventual "final solution".

- Heeresgruppe

- The largest German ground formation and was directly subordinate to the OKH. Mainly consisting of a number of “Armeen” with few directly subordinate other units. A Heeresgruppe operated in a large area and could number several 100,000 men.

- interbellum

- “Latin: Between war”. Years between the Great War and World War 2.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- SIPO

- ”Sicherheitspolizei”. Combination (since 1936) of the Gestapo and criminal police.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Images

In Estonia

On June 22nd, 1941, German forces invaded the Soviet Union with the Einsatzgruppen following closely behind. Because Estonia had been captured as early as August, Sonderkommando 1a was active in Latvia and Lithuania first. At various places in Lithuania, Sandberger’s units carried out a total of 41 executions. Along with Sonderkommando 2, Sandberger’s unit had incited local collaborators to destroy synagogues and to liquidate 400 Jews in the Latvian capital of Riga. In a German act of reprisal after the alleged butchering of a German soldier by a Jew, 100 Jews were executed in Riga. These practices were continued in Estonia. On August 28th, Sandberger and his unit moved into the capital, Tallinn. He reported the city as being almost unscathed and the Russian having retreated by sea at the last moment. Until August 30th, he counted 620 arrests. During those early days, various Bolshevist officials and Communists had been arrested including the vice-chairman of the Council of People’s Commissioners in Estonia, the chairman of the trade union and the secretary of the Communist party in Estonia.

A large part of the Estonian population welcomed the Germans as their liberators who would put an end to the Soviet occupation. Therefore, Sandberger concluded the Estonians showed a positive attitude towards the Germans. At the end of September 1941, he reported:"Generally speaking, the population is used to the fact that the Germans now call the shots in Estonia. All measures taken are being carried through obediently." In his view "the Estonians make any effort you can think of to support the Wehrmacht and to show their good will. In tracking down Estonian Bolshevists and taking them to court, they have frequently shown the desired cooperation."

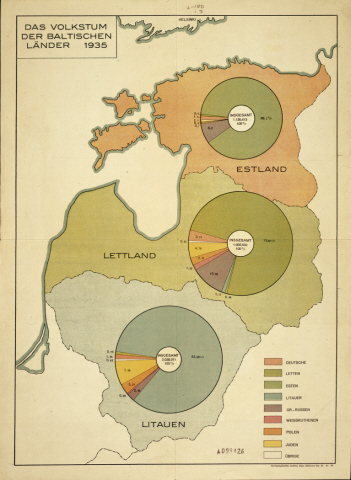

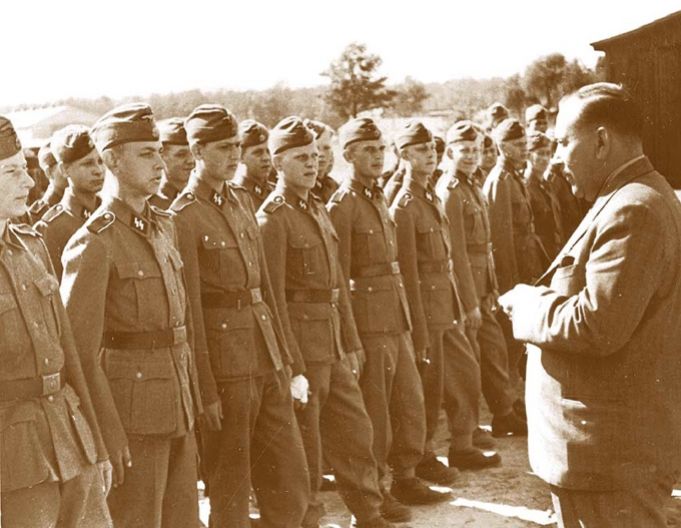

Sandberger had positive feelings about the Estonians, not only regarding their loathing of Bolshevism but also regarding their attitude towards Germans but from a racial point of view as well, Sandberger felt positive about the Estonians. In the western part of the country, many members of the Nordic race were living who in his opinion were suitable for Germanization. Incorporation of Estonia in the new European regime, ruled by Germany was, in Sandberger’s opinion: "considered by many Estonians the most logic and self-evident solution." Cooperating with the Reichsministerium für die besetzten Ostgebiete (state department for the occupied areas in the East) of Alfred Rosenberg (Bio Rosenberg) Sandberger appointed a three-man administration for Estonia under supervision of the German occupier. Estonian politician Dr. Hjalmar Mäe was made responsible for internal affairs and the police. He was closely involved in the Germanization of Estonia. Under his rule, the Estonian police retained its independence although it was restructured after the German police by Sandberger. Thanks to the close cooperation of the Estonian police, a large German force of occupation was not necessary. Sandberger also received support from an Estonian nationalistic militia, Omakaitse.

Messages of propaganda concerning the discovery of corpses in NKVD jails (the security service of the U.S.S.R.) and the exhuming of Estonians murdered by the Soviets, were used by the occupier to further fuel the hatred against the Communists. Sonderkommando 1a reported having taken 14,500 Communists into "precautionary detention", having executed another 1,000 and having placed 5,377 in concentration camps until mid January. Political prisoners were incarcerated in horrible conditions in prisons usually too small to house that number of inmates. Persecution of political opponents was never abandoned. As late as May 1943, Sandberger issued the harshest measures against Communists "without sentiments of objectivity and human considerations. Better to lock up 10 innocents than let even one guilty run free."

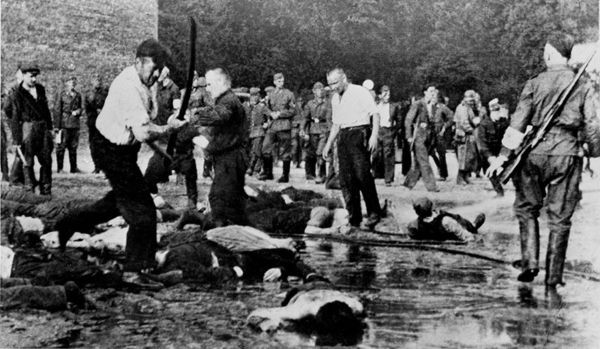

The Estonian Jews were also targeted by Sandberger’s Sonderkommando 1a. It was initially intended the Einstazgruppen should incite the local population to pogroms. They succeeded in this in Lithuania but failed in Estonia. The Germans concluded the Soviet occupation had fueled the hatred against Jews as they had allegedly played an important role in the administration but anti-Semitism among the Estonian population never rose to the level where pogroms could erupt spontaneously. Many Jews had already fled Estonia prior to the German occupation, leaving some 1,000 behind. Right after the invasion by the Wehrmacht, the Estonian militia had started arresting Jews. Sandberger took it a step further and ordered the arrest of all men and women fit for labor in Tallinn and Riga (Latvia) and surroundings to be employed as peat diggers. In other villages as well, including Pernau and Dorpat, Jews were temporarily imprisoned.

Sandberger also issued orders to wear the Star of David, along with all sorts of measures which applied to Jews in Germany as well, such as a ban on visiting public buildings and banning them from using public transport. He also had Jewish assets confiscated. Wehrmacht, SS and police confiscated furniture and personal belongings of Jews on a massive scale. Sonderkommando 1a was able to report on October 12th, 1941 that steps were taken in order to exterminate the Jewish population in Estonia. Up to that time 440 Jews had been executed by the Sonderkommando in cooperation with the Estonian militia. In the course of that winter the Estonian Jews, who had been deployed in forced labor up to then, were murdered as well. In a report of July 1st, 1942, Sandberger reported the death of 921 Jews, meaning he had successfully completed his mission: Estland ist Judenfrei (Estonia is free of Jews).

According to Sandberger’s records, a total of 60,000 persons were screened in the first year of occupation, 5,634 of them executed, 5,623 placed in a concentration camp and 18,893 imprisoned. The number of victims of the Estonian militia are not fully included in this. Apart from Communists and Jews, the same measures were also taken against Sinti, Roma and "anti-socials." Early July 1942, Sandberger reported: "some 33% of the previously arrested professional and habitual criminals have been executed." Sandberger also saw to the deportation of the "racially inferior" population of the Estonian part of the region of Ingermanland, also known as Ingria. These people were earmarked for forced labor in Germany and their former home region was designated for settlement of Volksdeutsche immigrants. Regarding Sandberger’s achievements during his tenure in Estonia, Michael Wildt judges him as follows: "Drawing up the balance sheet of Sandberger’s service in Estonia between 1941 and September 1943, one can call this almost impeccable in the sense of R.S.H.A. policy."

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- liquidate

- Annihilate, terminate, destroy.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Nazi report showing the ethnic groups in the Baltic states. Sandberger considered a large segment of the Estonians suitable for Germanization. Source: NARA.

Nazi report showing the ethnic groups in the Baltic states. Sandberger considered a large segment of the Estonians suitable for Germanization. Source: NARA. Estonian politician Dr. Hjalmar Maë greets Estonina volunteers of the Waffen-SS, 1944. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Estonian politician Dr. Hjalmar Maë greets Estonina volunteers of the Waffen-SS, 1944. Source: Wikimedia Commons.From Berlin to Tirol

In August 1943, SS-Obersturmbannführer Bernhard Baatz succeeded Sandberger as commander of Einsatzkommando 1a as his Sonderkommando had become known in the meantime. Later that year, Baatz would also be appointed chief of the SIPO and SD. Sandberger was transferred to Verona, Italy, arriving in September 1943. In his capacity as chief of the Gestapo, he was involved in hunting down Jews in northern Italy and in the establishment of an intelligence service in that part of Italy which had been liberated by the Allies. During the period Sandberger spent in Italy, the deportation of Jews in Rome was carried out. It started in October 1943 and a total of 1,015 Jews were deported to Auschwitz; only ten of them survived. The scale of Sandberger’s involvement in this is not entirely clear. About the same time, he contracted diphtheria, recuperating from it in his hotel room.

Sandberger returned to Berlin in early January 1944 where he spent the rest of the war working as chief of the department of organization and administration of Amt IV, the Auslandabteilung (foreign agency) of the SD in the R.S.H.A. headed by Walter Schellenberg. He acted as liaison to Heinrich Himmler and he was promoted to SS-Standartenführer in 1945. After the collapse of the Third Reich, Sandberger went into hiding in an alpine cabin in Austria for a while. On May 25th, 1945, he surrendered voluntarily to officers of the American 42nd Infantry Division in Kitzbühl in Tirol, Austria.

Due to his extensive knowledge of the German intelligence services, the Allies showed great interest in him. On June 23rd, 1945, interrogators of the 12th Army Group described him as a "well educated and capable man who had reached a high position in the hierarchy of the German intelligence system, despite his tender age." During his interrogations, Sandberger tried to play down his responsibility for the crimes that had been committed. He considered his section of the SD as democratic "since it was the only agency where criticism could be voiced openly to improve the fate of the population. His interrogators noted that he: " took extremely great pains to prove his administration in Estonia between 1941 and 1943 had been justified and was aimed at granting autonomy to the Estonians."

Definitielijst

- Infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- SIPO

- ”Sicherheitspolizei”. Combination (since 1936) of the Gestapo and criminal police.

Trial at Nuremberg

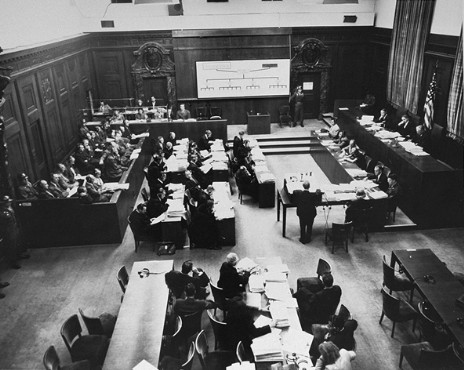

Sandberger could not escape prosecution and he was indicted, along with 23 others, during the so-called Einstazgruppen trial that took place in Nuremberg between September 1947 and April 10th, 1948 as part of the Nuremberg Military Tribunal or NMT. The sessions were held in the same courtroom in which the Nazi leaders had stood trial before the International Military Tribunal the previous year. This time, the tribunal was not jointly organized by the four major Allied powers but only by the Americans. All defendants had been leading officers of the Einsatzgruppen. They were charged with crimes against humanity, war crimes and membership of a criminal organization. Prime defendant was Otto Ohlendorf, former commander of Einsatzgruppe D.

During the proceedings, Sandberger hid behind Hitler’s orders. He admitted having had moral scruples against his order to exterminate the Jews but stated this order was legitimate as Hitler was the supreme authority and his orders had to be obeyed. He was afraid inobedience and dissidence would lead to his own martyrdom. He had made objections to this extermination order to his superior, so he claimed and he had requested frequently to be transferred but each time his request had been denied due to a shortage of personnel. Whether he spoke the truth about this is doubtful as a number of his colleagues were transferred to other posts at their own request after a while. Furthermore, Sandberger claimed not to have been responsible for illegal executions. In his words, Jews were not being executed by his own unit because they were Jews but only after extensive investigation had indicated they were Communist functionaries and therefore a legitimate security risk. He blamed the Estonian police and militia for the other executions of Jews. In his words, when murdering the Jews, they had been incited by the role the Jews had allegedly played during the seizure of power by the Communists.

During cross-examination however, Sandberger "blew his cover". When confronted with a document regarding the execution of 1,000 Communists, he estimated having been responsible for just 350 executions. During further examination, it appeared he was responsible for yet more deaths. The court stated Sandberger had issued a general order on September 10th, 1941 to arrest 450 Jews. Sandberger claimed he had done so in order to protect the Jews, "hoping that during their imprisonment, the Führerbefehl would be countermanded or the measures would be eased." During the execution of the Jews in the camps he claimed not to have been present and that the executions were carried out without his knowledge. He incriminated himself by his own statements though:

- Question: You assembled these men in the camps?

Answer: Yes, I gave the order.

Question: You knew that some time in the future, they could expect nothing else but death?

Answer: I hoped Hitler would countermand the order or change it.

Question: You knew of the possibility, bordering on certainty, that they were to be executed after they had been assembled?

Answer: I knew that possibility existed, yes.

Question: In fact, you were almost certain. Is that right?

Answer: It was likely.

Later on he admitted his guilt even clearer:

- Question: You assembled these Jews pursuant to the general order, this Führerbefehl, did you not?

Answer: Yes.

Question: And they were executed afterwards; they were executed, is that right?

Answer: Yes.

Question: By members of your unit?

Answer: By Estonian men who were subordinate to the leaders of my Sonderkommando; hence also to me.

Question: They were in fact executed by men under your command?

Answer: Yes.

Question: And then, pursuant to this Führerbefehl, these Jews were executed?

Answer: Yes.

In his final speech Dr. Stein, Sandberger’s defending counsel, attempted to lend legitimacy to Sandberger’s actions. In his view, the Germans in Estonia "were waging a life-and-death struggle which was conducted to the utmost and in the most cruel manner by partisans. Partisans," he argued, "posed a very special danger in Estonia as the most important lines of communication to Leningrad of the German Army Group North ran through Estonia." Therefore, Hitler had ordered "draconic measures," just like the Americans had done with the atomic bomb against Japan. Stein further argued, Sandberger had the law of war on his side. He quoted for instance Article 349 from the American Basic Field Manual Rules of Land Warfare: "Rebels during a war are those persons within the area under military occupation who take up arms against the forces of occupation or authorities appointed by the forces of occupation. When they are arrested, they may be sentenced to death."

According to Stein, Sandberger would always have adhered to the required procedures. "When Communist functionaries were executed in the area under his command or his responsibility, it did not happen in the form of executions but only when guilt had been ascertained in legal procedures and after the person arrested had been granted the opportunity to defend himself during these proceedings.". Sandberger had not only applied the legal procedures at all times but, according to Stein, it appeared from various statements that "he had always behaved correctly, decently and honestly." He quoted Swedish major Mothander who stayed in Estonia for a long time as representative of the Swedish government. According to him, "Sandberger was generally regarded as a decent man." He praised "his gift for humane friendliness and justice. Sandberger presented himself as a pure gentleman, either as an official or as a man."

"The measures against Communist activists were harsh," Stein finished his speech, " but considering the general situation of the war and the special position of Estonia they were justified, and the defendant was convinced of it." Sandberger refused to make a final statement himself.

Chief prosecutor Brigadier-general Telford Taylor attached no value to the arguments of Sandberger and his codefendants, that Jews were executed only when it had been proved they were partisans or criminals. "By stating the victims were partisans," the American declared in his final speech, "the defendants became entangled in a hopeless maze of contradictions and confusion. When their own reports indicated the victims were Jews, they responded that all Jews were partisans. When the reports indicated executions of partisans and they were asked how they knew these victims were partisans, they answered they had to have been partisans because it had been ascertained they were Jews."

Furthermore, Taylor observed "the executions never met the requirements laid down in the laws of war." They had been "meticulously planned long before the Germans launched their attack. Furthermore, nothing is laid down more clearly in the laws of war than that no combatant who has surrendered - regardless of being a partisan, spy or guerilla fighter – and no civilian may be executed without having had at his disposal a court martial or a proceeding before a military court to determine his guilt. Defendants have not even tried to meet this requirement."

The judges were not impressed by Sandberger’s defense. In its verdict, the tribunal stated that Sandberger willingly obeyed the Führerbefehl: "As soon as the Kommando had reached its first stop, it began its criminal work." Based on reports by the Einstazgruppen, Sandberger’s responsibility for mass executions of Jews and alleged Communists was proved. Although he denied having been present at the executions, this "exonerated him in no way from his legal responsibility for the action," so the court ruled. Chairman of the tribunal, Michael Musmanno even said Sandberger "gave the impression of someone telling tall stories in a bar." Emphasis was also placed on the incredibility of Sandberger’s argument that each victim was subjected to an individual investigation as to his guilt and that his prisoners could appeal against a sentence.

Sandberger’s attempt to put the blame on local collaborators was also dismissed by the tribunal. It was determined that for specific operations, the Estonian militia was under Sandberger’s jurisdiction and control. No value was attached to Stein’s argument either, Sandberger had had to respond to a Communist uprising. In the opinion of the tribunal "the leaders of the Einsatzgruppen themselves attempted to incite to riots by launching pogroms." As his guilt as to executions and other crimes had been proved and his membership of the SS and other criminal organizations was a definite fact, the court sentenced Martin Sandberger on April 10th, 1948 to death by hanging. 14 other defendants heard the same verdict but ultimately, only four of them would be actually executed. Sandberger was not among them though.

Definitielijst

- crimes against humanity

- Term that was introduced during the Nuremburg Trials. Crimes against humanity are inhuman treatment against civilian population and persecution on the basis of race or political or religious beliefs.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- moral

- The will of the troops/civilians to keep fighting.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- war crimes

- Crimes committed in wartime. Often concerning crimes committed by soldiers against civilians.

Images

After Nuremberg

It was to Martin Sandberger’s advantage that during the period of his trial, a new historical era had begun: the Cold War. The Soviet Union did no longer belong to the former alliance, headed by the Americans but now she was the new enemy instead. Germany had been split in two. While the Deutsche Demokratische Republik (D.D.R.) in the east was under Soviet influence, the Bundesrepublik Deutschland (B.R.D. or federal republic) became the new ally. Shortly after the verdicts in the Einsatzgruppen trial had been passed in June 1948, Berlin was sealed off by Joseph V. Stalin (Bio Stalin) so access to the western part of the city, governed by the Allies, was only possible by air. Neither West Berlin nor the Federal Republic were to fall in Soviet hands so a good relationship with West-German authorities was imperative to the Americans. Death sentences against German civilians had a bad influence on this relationship. Therefore in many cases, pleas by West-German politicians and clergymen not to execute their fellow countrymen were accepted.

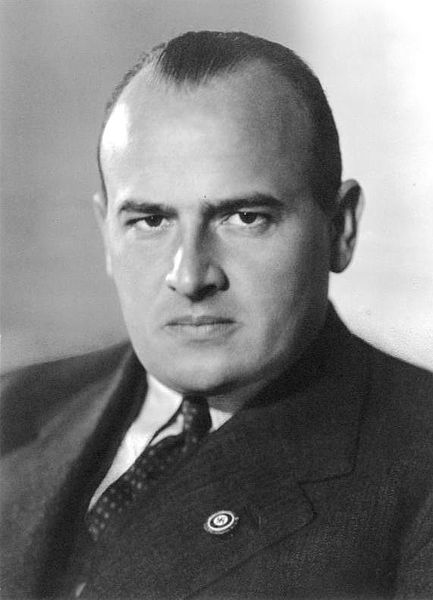

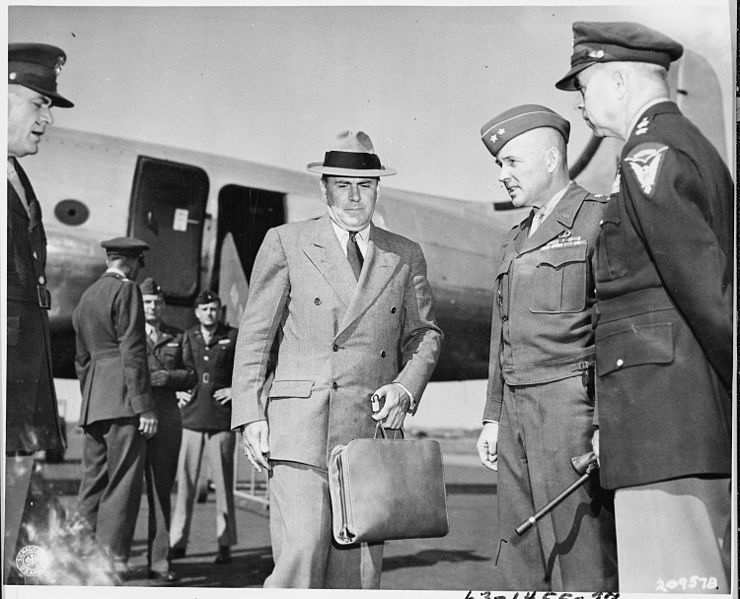

Out of the 15 defendants of the Einsatzgruppen trial who had been sentenced to death, only four: Paul Blobel (Bio Blobel), Werner Braune, Erich Naumann and Otto Ohlendorf ended up on the gallows on June 7th, 1951. Sandberger escaped the death penalty although on August 28th, 1950, an advisory committee had concluded that in his case the death penalty was justified. John McCloy, the High Commissioner of the American zone of occupation did not accept the advice and decided to change Sandberger’s death penalty to life imprisonment. During the years he was imprisoned in Landsberg, many prominent West-Germans advocated Sandberger’s accelerated release, including Theodor Heuss, the first president of the federal republic, Carlo Schmid, deputy chairman of the S.P.D. (Socialist Party of Germany) faction in the Bundestag and vice-president of the Bundestag, Gerhard Müller, president of the federal state of Württemberg-Hohenzollern and Martin Haug, Bishop of Württemberg.

Carlo Schmid, Sandberger’s mentor in Stuttgart of pre war times, remembers him as an " industrious, intelligent and gifted lawyer who on the one hand fell into the intellectual nihilism of the time – the Nazi period – but who on the other hand clung tenaciously to the formal world of bourgeois mentality." In his view, Sandberger would have become a decent civil servant, had it not been for the Nazi regime. American Senator William Langer from North Dakota, a fervent anti-Communist, also dedicated himself to Sandberger’s accelerated release. "Just like you were an officer in a field artillery unit during World War One, " he wrote in a plea to President Harry Truman, "Martin Sandberger was an officer in a German unit, fighting in Russia during World War Two. Ordered by higher authorities, he was forced to do many unpleasant things, including a number of executions. Some of his decisions must have cost him just as much mental agony as your decision to drop the atomic bomb."

Sandberger was released on May 5th, 1958. He was met by Eberhard Müller, theologian and principal of an Evangelic Academy and his brother Bernhard, member of parliament in Baden-Württemberg for the conservative C.D.U. (Christian Democratic Union). Bernhard Müller was general representative of the Lechler group, an enterprise that produces industrial sprinkler systems. In 1958 he could offer Sandberger the job of legal advisor. Sandberger rose to the "right hand man and respected member" of the management, according to Walter H. Lechler, today’s chief executive officer of the Metzingen based company. According to him, the SS veteran had enhanced his knowledge of the tax system considerably during his imprisonment in Landsberg. Not a word was uttered about his experiences during the war.

Efforts to get Sandberger sentenced again for his crimes were not made during the next few years. He did appear as a witness though, during the Einstazgruppen trial in Ulm, among others, where 10 members of an Einsatzgruppe stood trial for the murder of 5,500 Jews in the former frontier region of Germany and Lithuania. As late as May 1970, investigation into Sandberger was re-opened by the public prosecutor in Stutttgart. He was charged for instance with executing Jews and Communists in Estonia. His counsel, Fritz Steinacker, a former Luftwaffe bomber pilot who had also represented Josef Mengele (Bio Mengele) and other Nazi criminals, asked the court to reckon with the deteriorating health of his client. The case was closed, based on the Transition Agreement between the forces of occupation and the German republic which stipulated that German citizens, once sentenced by the Allies could not be sentenced again. A charge against him, concerning the murder of Jews from France who had been deported to Theresienstadt was dropped for the same reason.

When new evidence became available after the fall of the Iron Curtain, a new case against Sandberger was not opened any more. Since his sentencing in Nuremberg, journalists had no longer paid any attention to him. Shortly before his death, a journalist from Der Spiegel paid him a visit. It took him no trouble at all to track him down in his apartment in a home for the elderly in Stuttgart. His name was openly displayed on the letter box. The young Nazi officer he had been during the war had become a frail man in the meantime, 98 years of age. He liked to have cheering passages from the Bible read to him by a lady who was taking care of him. He had a sauna and lavish three-course meals at his disposal. He was not happy with the questions of the journalist. He claimed to have few memories of his Nazi period. He voiced no comment when asked whether his death sentence was justified. After he was asked whether he felt sorry after all those years, he kept silent for a while. Then he answered: "I don’t want to talk about it." Those were probably the last words of Sandberger that were recorded. He passed away on March 30th, 2010.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Luftwaffe

- German air force.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Theresienstadt

- City in the Czech Republic. Here the Nazis established a model concentration camp.

Images

Execution of a war criminal in Landsberg, 1946. In order to appease the west Germans, such executions were limited by the Americans. Source: NARA.

Execution of a war criminal in Landsberg, 1946. In order to appease the west Germans, such executions were limited by the Americans. Source: NARA. John J. McCloy, then assistant Secretary of Defense, arrives in Berlin to attend the Potsdam Conference, July th, 1945.

John J. McCloy, then assistant Secretary of Defense, arrives in Berlin to attend the Potsdam Conference, July th, 1945. Information

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Sources

- MAYR, W., "The Quiet Death of a Nazi", Der Spiegel, 04-15-2010.

- Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals, Volume IV, The Einsatzgruppen Case.