Introduction

Franz Stangl is seen by many as the role model of the loyal and obedient police officer in any circumstance. Because of his upbringing in an authoritarian family and an education where blind obedience came first, he has carried out his tasks with meticulous dedication to which many hundreds of thousands have fallen victim. The life of Stangl was one of an inconspicuous civil servant who became a conscious cog in the machinery of the Holocaust.

Austrian police officer Stangl started his career in the mass murder factory in the Nazi euthanasia program and continued his work as commander of the extermination camps Sobibor and Treblinka respectively. During the last years of he war he was active in northern Italy and Yugoslavia.

During his imprisonment in Düsseldorf, Germany, he had many conversations with British-Hungarian journalist Gitta Sereny over a period of weeks. This article includes numerous quotes from her report of these meetings.

Definitielijst

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

Images

Youth and early career

Franz Paul Stangl was born March 26, 1908 in Altmünster, Austria; the second child – he had a sister 10 years his senior – of a night guard. His father had served with the dragoons in the Imperial Austro-Hungarian army and ruled the family with an iron military discipline. Stangl said about his father: "

When he was 15 years of age, Stangl had enough of school. He went to work as an apprentice in a weaving mill and on completion of his training in 1926, he was the youngest master weaver in Austria. His great hobby was playing the cither, he was an active member of the local cither club and gave lessons on the instrument. A career in the textile industry seemed a natural choice, regarding his training, but he had to quit in 1931 for reasons of health. He applied for a job in the police, was accepted and followed basic training with the police in Linz at their training center Kaplanhof. It is conspicuous how Stangl would later describe his instructors as sadists. After a year’s training he was deployed as junior police man, first in the highway police, later on in the special police force. He completed his training in 1933. When he stumbled upon a secret arms cache of the – illegal- Austrian N.S.D.A.P. in a forest, he was awarded the Adler medal and was allowed to begin training as a detective in the Kriminalpolizei – Kripo or criminal police. In the fall of 1935, he was transferred to the political branch of the Kripo in Wels, the second largest city in Upper Austria after Linz.

In March 1938, after the annexation of Austria by the German empire, Stangl joined the N.S.D.A.P., membership number 6,370,447 and became member number 296,569 in the SS. By the way, in 1938 he "corrected" his year of entry into the N.S.D.A.P. in the personnel files of the police to 1936 when the Austrian N.S.D.A.P. was still illegal. After the war, Stangl gave as his reason that membership of the party after the Anschluß could mean trouble for him as a police officer. Whatever, Stangl’s career in the police blossomed. In January 1939, the political branch of the Kripo was taken over by the Gestapo and transferred to Linz. Stangl was promoted to Kriminaloberassistent and put to work in the Judenreferat. He left the Catholic church that same year, as ordered by his superior.

Meanwhile, on October 7, 1935, Stangl had married Theresa (Thea) Eidenböck. They were to have three daughters. In 1936 Brigitta – Gitta – was born, Renate followed in 1937 and Isolde in 1944.

At the end of 1940, Stangl was promoted to Polizeileutnant (chief inspector of police) and transferred to an institution with the innocent name "Gemeinnützige Stiftung für Heil- und Anstaltspflege" (Foundation for the general benefit of health care and institutions). Behind this name however, the organization that carried out the Nazi euthanasia program was hidden. The purpose of he program was to "preserve the racial purity of the Germanic people" by systematically murdering those people who were deformed, disabled or suffering from mental disorders. Headquarters was located in a respectable villa at Tiergartenstraße 4 in Berlin. Aktion T4, after the abbreviation of the address, was the code name for these systematic murders - in close cooperation with the SS - of some 70,000 disabled patients by doctors and nurses in the period from October 1939 to August 1941. Extermination took place in six euthanasia institutions.

After a short stay in Berlin, Stangl became office chief in one of these institutions, the NS-Tötungsanstalt (institute for killing), Schloß Hartheim near Linz in November 1939. In the course of Aktion T4 over 18,000 physically and mentally disabled persons were gassed here by means of carbon monoxide (CO). Stangl, who signed all documents with the alias Staudt by the way, was responsible for the smooth running of the administration. The actual liquidation of the patients was carried out by doctors and nurses. Stangl’s work – according to his own words – was mainly focused on the handling of the inheritances of the victims, affairs concerning insurances and costs and problems regarding the children of those who had been killed.

Definitielijst

- Kripo

- Kriminalpolizei. Criminal investigation agency. Ordinary civilian police of Nazi Germany.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

Images

Euthanasia

Stangl gained valuable experience in the techniques of deceit that would suit him well as commander of extermination camps later on. For instance, death certificates (naming feigned causes of natural death) were recorded in the civil registration of towns where other euthanasia institutions were located. The purpose was to make relatives believe their family member had died in another institution that was also far away. Personal investigation by the next of kin as well as undesired research by them was rendered more difficult that way. Relatives were misled further by the delivery of an urn containing the ashes of "their" family member with a bill for the cost of cremation, sent by an institution where liquidation had not taken place at all. Moreover, the next of kin received bills for food, housing and care over periods of months whereas the persons involved had been killed right after arrival.

By the way, on Sundays, the staff gave concerts in the courtyard of Hartheim with Stangl playing the cither.

In 1971, Stangl told Gitta Sereny about what went on in Hartheim during Aktion T4. Patients from institutions all over the Reich were transported to Hartheim by bus. Regarding their mental state, some of them were unaware of what was in store for them but others were mentally healthy and for them, various forms of deceit were being applied. They were told they had arrived in a special clinic where they would receive better treatment. On arrival, they underwent a short medical examination and subsequently they were taken to a "shower room" in which they were gassed.

The locations for euthanasia can be considered a dress rehearsal for what was to unfold in the east. Stangl and others, who would later became the executors of the mass extermination of the Jews, received their training to organize assembly line liquidation in Aktion T4. About 100 staff members of the euthanasia centers who were considered capable were sent to the extermination camps in the east in 1942 where they would play a leading part in the Endlösung, including Franz Stangl.

Definitielijst

- Endlösung

- Euphemistic term for the final solution the Nazis had in store for the “Jewish problem”. Eventually the Endlösung would get the form of annihilating the entire Jewish people in extermination camps.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

Images

Sobibor

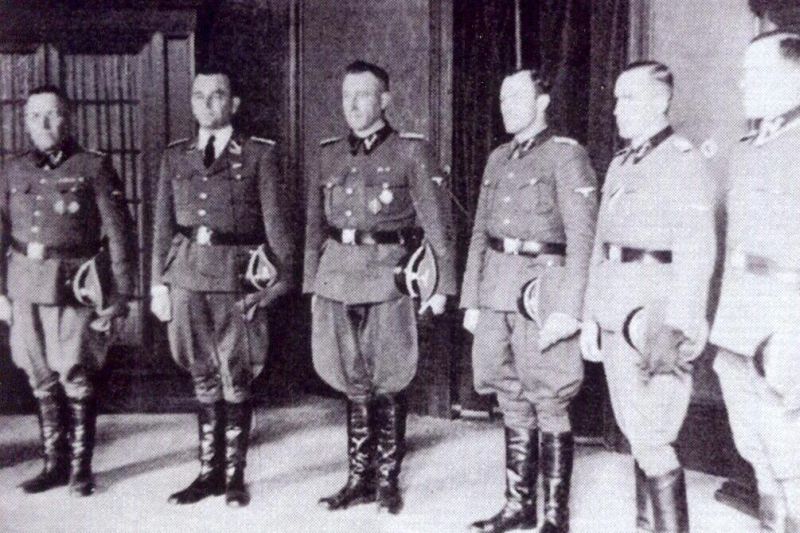

In February 1942, Stangl was back in Hartheim after a short stay of one month in the NS-Tötungsanstalt in Bernburg, Sachsen-Anhalt and was summoned to the Tiergartenstraße again. There he received order to travel to Poland and report to SS-Gruppenführer Odilo Globocnik (Bio Globocnik) in Lublin in March; chief of Aktion Reinhard, code name for the mass extermination of the Polish Jews in the General Government in 1942 and 1943. In March, Stangl reported to Globocnik in Lublin punctually. He was promoted to Polizeioberleutnant and he was ordered to complete the construction of the extermination Camp Sobibor which had already begun.

After the war, Stangl told Gitta Sereny about his ‘job interview’ with Globocnik. He met his boss in the garden of SS headquarters in Lublin.

- "It was a beautiful, warm day in spring. The grass was green, the trees were in full bloom and spring flowers popped up everywhere. Globocnik was sitting on a bench with a beautiful view of the lawn. He greeted me very warmly. ‘Please sit down’ he said and he patted the bench next to him. ‘Tell me everything about yourself’. He wanted to know everything about my school, my career and my family. It was clear to me this was some kind of test to find out whether I was really suitable for my new task. After I had told him everything he said I undoubtedly knew the army had suffered a major setback in the east. The SS had to come to the rescue. He said it had been decided to establish a number of supply camps in Poland in order to make supplying the troops with equipment, weapons and so on easier. He intended to entrust me with the construction of such a camp – it was called Sobibor. He called an adjutant and ordered him to bring the plans. Those displayed the design of a camp: barracks, railways, fences, gates. Globocnik continued: ‘Construction has started but we have Polish workers there. Everything proceeds so slowly, I think they are sleeping. What I need there is somebody who can put all of it in motion and I think you are the man for the job’. Then he said I should drive to Sobibor the next day – and that was all."

In April 1942, Franz Stangl arrived in Sobibor charged with the task to accelerate the completion of the extermination camp as commander. He has always denied he knew it was an extermination camp, as appears from the job interview with Globocnik mentioned above. Only after arrival he would have been faced with the facts and would have done everything in order to be transferred. Stangl claimed he had occupied himself with the building activities only. As questionable Stangl’s credibility may be, under his direction the camp was completed in record time. In May 1942, extermination camp Sobibor was fully operational and gassings could be carried at maximum capacity. In the first two months of Stangl’s command, some 100,000 Jews were gassed and subsequently cremated. After the war he stated:

- "As to the question, what is the largest amount of people that can be gassed in one day, I can declare the following: In my estimate, a transport of 30 cars holding 3,000 people could be liquidated in three hours. If work continued for some 14 hours,, between 12,000 and 15,000 persons were exterminated. On many days the work lasted from the early morning until late in the evening."

In June 1942, his wife and two children also came to Poland. Initially they lived some 18.5 miles from the camp in the provincial town of Chelm, but soon, the Stangl family took residence in a former estate close to the village of Sobibor, a few miles from the camp. Stangl frequently rode his horse through the forest to and from work. The Stangl’s did not stay in Sobibor for long, though. In September 1942, Stangl was transferred to the extermination Camp Treblinka to clear up the mess camp commander Irmfried Eberl had created. He sent his family back to Austria. In Sobibor he was succeeded by a former colleague from Hartheim Castle, SS-Hauptsturmführer Franz Reichleitner.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

Images

Treblinka

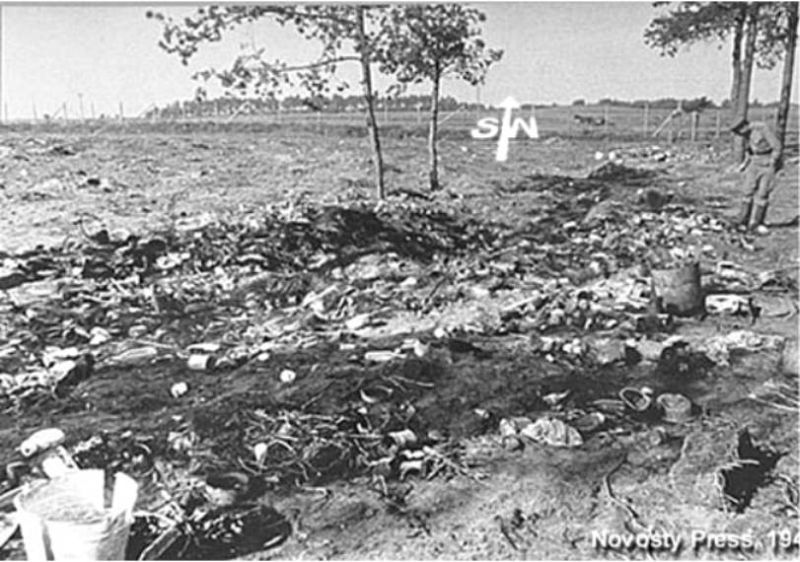

In September 1942, Stangl arrived in extermination camp Treblinka to succeed commander Dr. Irmfried Eberl, an Austrian physician who had previously been Stangl’s superior during his short stay in the euthanasia center Bernburg. Eberl had fallen into disgrace with the leadership of Aktion Reinhard as he appeared to be unable to "process" the incoming transports in the largest of the extermination camps in an efficient way. Countless corpses lay scattered all over and outside the camp grounds and the undisciplined camp staff could not keep up with burials in mass graves.

After the war, Stangl described what he encountered on his arrival in Treblinka. He painted a picture that is possibly not free of exaggeration:

- "I drove up there with an SS driver. We could already smell it miles away. The road ran alongside the railway track. When we were 15 or 20 minutes away from Treblinka, we saw bodies lying alongside the tracks, first two or three, later on more and when we arrived at the station, there were hundreds of them – they just lay there – obviously for days in the heat. At the station was a train full of Jews, some dead, others still alive .. that train looked like as if it had already been there for days. When I arrived in Treblinka, that day was the most horrendous of what I had seen in the entire Third Reich. It was the Hell of Dante; Dante’s Hell had come to life.

When I arrived in the camp and got out of the car on the platform, I sank up to my knees in money. I did not know where to walk. I waded through bank notes, coins, gemstones, clothing. The whole platform was littered with it. The stench was indescribable. Hundreds, no thousands of bodies were lying around, decomposing, rotting. Across from the platform, in the forest on the far side of the barbed wire and all around the camp there were tents and bonfires. There I saw groups of Ukranian guards and girls – whores I discovered later - from the entire region, dead drunk, dancing, singing, making music .."

Stangl was a different kind of person than his predecessor and he swung into action immediately. Just as in Sobibor, he emerged as the efficient and dedicated organizer of mass murder in Treblinka. Odilo Globocnik called him "the best camp commander who made the largest contribution to the entire Aktion Reinhard". It filled Stangl with pride.

Just like in Sobibor, Polizeileutnant Stangl was the highest ranking among the German camp staff. As camp commander he was responsible for the perfect running of the camp organization as a whole and for the course of the mass liquidations in particular; all this of course pursuant to orders and directives from Odilo Globocnik and as local representative of Christian Wirth (Bio Wirth), the inspector of the three extermination camps of Aktion Reinhard (Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka). Delays in the mass extermination like they had occurred under Eberl, should not happen again. In his first weeks as commander and under the watchful eye of Wirth, Stangl re-established the camp organization from the ground up. Characteristic was one of the first measures he took after his arrivals: placing buckets in the so-called Schlauch (hose), the narrow passage through which the prisoners were herded towards the gas chambers. In Sobibor, Stangl had noticed that the deportees relieved themselves everywhere when they ran through the Schlauch or were waiting there. The buckets did served their purpose.

On a larger scale he ordered more and larger gas chambers to be built. Under his direction, the process of mass extermination was meticulously laid down in writing step by step and the staff was re-organized. In Treblinka he introduced permanent teams of Jewish prisoners who were to perform all kinds of jobs in the extermination process such as unloading the trucks and clearing up the gas chambers. He saw to it in particular that the barracks, overflowing with clothing of liquidated Jews were emptied, that everything was sorted out and that valuables, which were scattered all over the place were collected and stored. In addition he saw to it that the scattered bodies outside the camp were disposed of. He also had the so-called railway station built, complete with ticket counters and signs with fictitious timetables. In order to suggest connecting trains, signs were put up with messages like ‘To Warsaw’ and ‘To Bialystok.’ It was intended to make those arriving on the deportation trains believe they were in a transit camp. Methods of deception with which experience had been gained in the euthanasia centers of Aktion T4 were also applied here.

Soon, Stangl’s deputy, SS-Oberscharführer Kurt Franz took over the direction of the daily order of business in the camp and within a short time, the continuously operating murder factory in Treblinka evolved into a well oiled machine. It offered Stangl the opportunity to direct more from the background and focus on organizational issues. All correspondence and written material passed through his hands. He limited himself now to inspection and control rounds during the processing of incoming transports and the other issues in the camp such as clearing the gas chambers after a gassing, the burying and later cremating of the corpses. He got the undisciplined and murderous Ukranian guards in line by threatening them with severe penalties and the Arbeitsjuden also enjoyed his attention. He had living quarters furnished for them with bunks, he set up rules about the work to be done and personally inspected the workshops and the various Arbeitskommandos. He sometimes attended roll calls of the Arbeitsjuden and delivered speeches warning them against attempts at escape or threatened with penalties (like execution) when the work was not done properly. Despite the enormous number of incoming transports, delays in processing them was almost a thing of the past under Stangl’s direction.

After the war, Stangl claimed his dedication had nothing to do with ideology or anti-Semitism. From his interview with Gitta Sereny:

- "They – the Jews – were weak, they let everything happen. They were people with whom there was no mutual similarity, no possibility of communication; that way, contempt is created. I never understood why they gave up so easily".

Various witnesses have testified that Stangl, in contrast to his subordinates, took a quiet and reserved attitude towards the Arbeitsjuden and there was never any question of sadism on his part. Not one single case is known in which he mistreated or killed a prisoner with his own hands or even raised his voice but then he hardly made contact with them. The prisoners usually saw him from a distance. Prisoner Samuel Rayzmann remembers the commander as follows:"Franz Stangl usually stood on the earthen embankment between the camps. (Treblinka was divided in two camps). He stood there like a Napoleon watching his troops."

After the war, Stangl himself spoke about that distance also:

- "I rarely saw them (the prisoners) as individuals. they always formed one enormous crowd. How can I explain? They were naked, bunched together, running, spurred on by whips."

And: "Cargo, they were cargo. I think it began the day when I saw the Totenlager (death camp) of Treblinka for the first time.. I remember Wirth standing there, next to the pits filled with black and blue corpses. That had nothing to do with humanity – it could not have anything to do with that; it was a mass of rotting meat. Wirth said: ‘What should we do with this garbage?’ I think I started them seeing them unconsciously as cargo at that moment… This was the system. Wirth had invented it. It worked and because it worked it was irreversible."

Despite the distance, all Arbeitsjuden saw Stangl as the camp commander. They called him the "Oberleutnant mit der Feldmütze" (Lieutenant with his field cap), after the small beret he always wore. Initially, Stangl was always dressed in a spotless white uniform coat in the camp. In addition he held a small riding whip in contrast to his subordinates who were provided with long leather whips. The button of his whip was adorned with a monogram made for him in Sobibor from the gold from murdered Jews. After he had been promoted to SS-Obersturmfühere in December 1942, he wore the field gray SS uniform.

In August 1943, a revolt broke out in Treblinka. (See: Revolt in Treblinka). Some 400 prisoners managed to obtain weapons from the depot and in the ensuing skirmishes, 200 to 250 prisoners managed to escape, the majority of which was tracked down again in the surroundings. They were executed immediately on return to the camp. The last two transport with Polish Jews arrived in Treblinka on August 18 and 19. After they had been liquidated, the last prisoners left the camp on October 20, 1943 by train to Sobibor where they were gassed immediately on arrival. The 25 Arbeitsjuden who remained behind were executed on the spot. Subsequently, the last SS men left the camp which was then razed to the ground in a short time. This meant the end of Stangl’s career as camp commander.

Definitielijst

- Aktion Reinhard

- Code name for the secret Nazi operation to murder all Jews in the Generalgouvernement of the extermination camps Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka. This operation was also known as Aktion Reinhardt or Einsatz Reinhard(t).

- heat

- High-explosive anti-tank warhead. Shaped charge projectile to punch through armour. Used in e.g. bazooka or in the Panzerfaust.

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

Images

Northern Italy

A short time after the uprising in Treblinka Stangl, meanwhile promoted to SS-Hauptsturmführer, transferred to the so-called Operationszone Adriatisches Küstenland (Area of operations on the Adriatic coast) along with Odilo Globocnik, Christian Wirth and 120 colleagues from Aktion Reinhard. This zone was created on October 1, 1943 from the areas in northern Italy, occupied by the Wehrmacht after the Italian government had signed the armistice with the Allies in the south of the country.

In the Operationszone, Stangl was deployed in the fighting against partisans and the deportation of Jews from northern Italy but relatively little is known about his activities at that time. He was part of the Sonderabteiliung Einsatz R (R for Reinhard) which had recently been established in the area. It was an independent branch of the SS and police in the area and was commanded by Odilo Globocnik who meanwhile resided as Höherer SS- und Polizeiführer in Trieste. The task of the Sonderabteilung entailed first of all deportation and extermination of the Jews in northern Italy, confiscation of their possessions and in addition persecution of political opponents and the fight against partisans.

Commanders of the various units of the Sonderabteilung had all been commanders of the extermination camps in Poland. Initially, Stangl was chief of Einheit R III in Udine. After Franz Reichleitner (his successor as camp commander of Sobibor) had been shot by partisans in January 1944, Stangl succeeded him as commander of Einheit R II in Fiume (today Rijeka in Croatia). He remained in that function until May/June 1944 when he was appointed commander of Einheit R IV in Mestre. At the end of 1944, Stangl fell ill: he ran a high fever and his body was covered in blue spots. He spent a while in a field hospital and when he received order to report in Berlin once more he joined his family, which meanwhile had moved to Lembach, Austria, in the chaos of the last months of he war in April 1945.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Arrest, escape and conviction

Stangl was arrested in Lembach by the Americans in July 1945 and detained in the prison camp Glasenbach near Salzburg. He was initially considered an SS man who had been active in the war against partisans in Yugoslavia and Italy. His activities in the extermination camps in Poland were still unknown. Just prior to his release in 1947 it became known that Stangl had been active in Hartheim Castle at the beginning of the war. Hence he was turned over to the Austrian authorities who placed him in temporary detention in Linz for his participation in Aktion T4. The next year, the so-called Hartheim trial was begun in Linz against those who had been active there in the euthanasia program.

When Stangl heard from his wife that a subordinate, a former driver of the Hartheim personnel had been sentenced to four years imprisonment he escaped from the half open prison in Linz, along with Gustav Wagner, former deputy commander of Sobibor and colleague of Einheit R. Stangl fled on foot to Rome via Graz and Florence where Catholic bishop Alois Hudal helped him to get a Red Cross pass and a visa for Syria. In Damascus he initially worked as a weaver. In May 1949 he had his family join him and from December 1949 he was working as an maintenance technician with the Imperial Knitting Company in Syria.

In 1951, the family emigrated to Brazil where Stangl worked as a weaver in Sao Paulo and later as technician in the Sutema textile factory. His wife Theresa found employment in the department of financial administration of the Mercedes-Benz works and via her contacts, Stangl found employment in October 1959 in the Volkswagen plant near Sao Paulo. In the meantime, they lived in a roomy house of their own in a quiet suburb, openly under their own name as registered with the Austrian consulate.

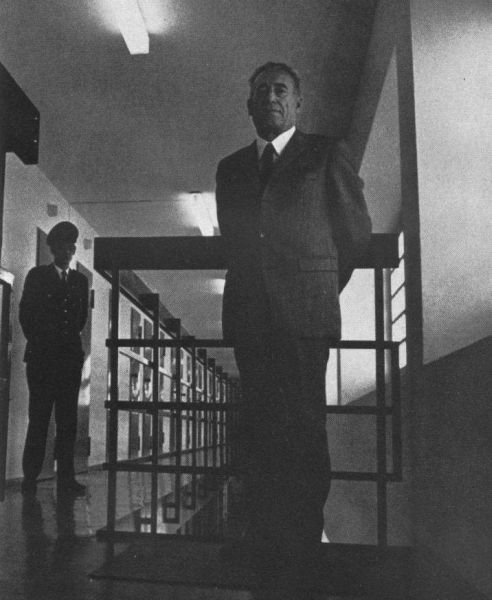

As late as 1961, Stangl’s name appeared on an official Austrian list of wanted persons. Simon Wiesenthal tracked him down in 1964 and on February 26, 1967, he was extradited to the German Federal Republic. He stood trial in Düsseldorf; the indictment read complicity in the mass murder of 1,200,000 persons. The trial opened on May 13, 1970 and on October 22, Franz Stangl was sentenced to life imprisonment for complicity in the murder of 900,000 persons.

Stangl appealed his sentence but he died on May 28, 1971 from a heart attack in the prison in Düsseldorf. Shortly before, Gitta Sereny had still talked with him.

Images

Epilogue

Stangl has never claimed anti-Semitism as motive for his participation in the mass extermination. Instead, after the war he attempted to present himself as a victim of his own fears and of the methods of intimidation the Nazis would have subjected him to. Turning points in his career he argued away, so to speak, by stating he simply had had no other choice than to do what he was ordered to do and to go wherever his superiors sent him. That applied to his leaving the Catholic Church, his involvement in the euthanasia program and eventually to his appointment as commander of two extermination camps as well. Gitta Sereny concludes Stangl was a man without any moral courage who inwardly despised himself.

In any case, Stangl was never bothered by his conscience. In conclusion three quotes in this connection from his interviews with Gitta Sereny:

- "At the police academy they tought us that a crime must meet four basic requirements: occasion, subject, the act itself and the free will. When one of these elements is missing, there is no question of a punishable act. If the occasion was the Nazi government, the subject the Jews and the act the exterminations, I can say that for me personally, the fourth element, the free will was missing.

My conscience is clear, I only did my duty.

My only guilt is I am still here…. I should have died. That is my guilt".

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- moral

- The will of the troops/civilians to keep fighting.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

Images

Information

- Article by:

- Robert Jan Noks

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- ARAD, Y., Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, Indiana University Press, Bloomington (USA), 1999.

- HILBERG, H., De vernietiging van de Europese Joden, Verbum, Laren, 2008.

- SERENY, G., Into that darkness, McGraw-Hill, 1974.

- www.zeit.de

- www.auschwitz.dk

- www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk

- www.economy-point.org

- de.wikipedia.org

- de.wikipedia.org

- www.jewishgen.org

- en.wikiquote.org

- www.facinghistory.org

- www.pacem.no

- www.nizkor.org

- www.simon-wiesenthal-archiv.at

- www.holocaust-lestweforget.com

- www.verzet.org

- en.wikipedia.org

- www.liberales.be