Introduction

Regarding the Holocaust, Auschwitz immediately comes to mind. It is the best known Nazi extermination camp. It is often forgotten though that Auschwitz was not the only extermination camp, in addition there were Camp Sobibor, Belzec and Treblinka. This article is about the last camp. It was an element of Aktion Reinhard and perhaps the most efficient extermination camp. Over a period of 18 months, approximately 800,000 people were killed here.

Definitielijst

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

Images

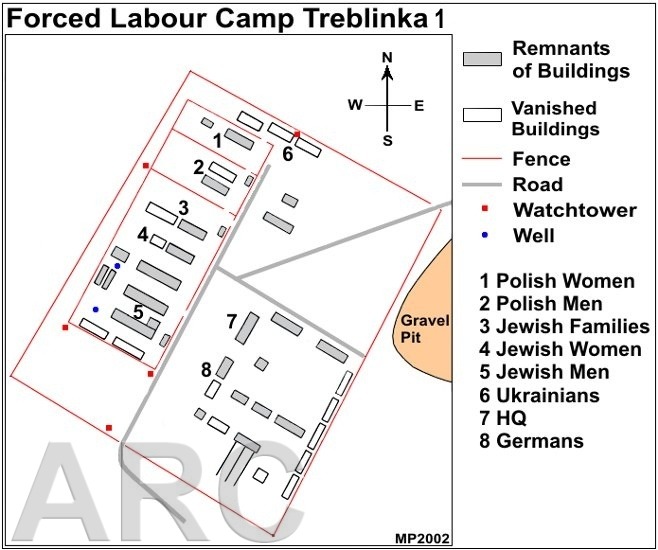

Labor camp Treblinka I

The history of Treblinka begins in 1939 when Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler appointed Odilo Globocnik SS- und Polizeiführer in the Lublin district of the General Government in Poland. On July 17, 1941, he was even named Beauftragter des Reichsführers-SS für die Errichtung der SS und von Polizeistützpunkten im neuen Ostraum, making him responsible for the preparation of the newly captured territory in the east for colonization by the SS. Jews as well as Poles were to be resettled in designated areas where they would perform forced labor for the Germans. Later on he became chief of Aktion Reinhard, named after Reinhard Heydrich.

Later that same year in November, Arbeitslager (Labor camp) Treblinka was established in the vicinity of the little town of Malkinia Górna in the region Mazovia, 31 miles north of Warsaw. Jews, Poles and Ukrainians who had violated a rule or a ban by an agency of the General Government were locked up here. Most of them found employment in the stone quarry. Others worked in the workshops in the camp whilst most women were put to work on the camp farm. It was not a large camp as to the number of prisoners: there were always between 1,000 and 2,000 prisoners. In principle, the imprisonment lasted between two and six months but the majority of the prisoners did not survive the harsh forced labor. In the three years of its existence, Treblinka has housed a little over 20,000 people of whom about half did not survive the harsh regime.

In charge of the camp was SS-Sturmbannführer Theodor van Eupen, born April 24, 1907 in Düsseldorf. He commanded a small staff of 15 to 25 German SS men including SS-Oberscharführer Werner Hinze and SS-Unterscharführer Alexander Mitter. Also at his disposal was a special guards unit consisting of 90 men, all trained in the SS-Trawniki camp in the Lublin district.

Van Eupen remained in command of Treblinka until it was liquidated in July 1944 owing to the arrival of the Red Army. Aleksej Kolguschkin, one of the Trawniki guards told about the liquidation of the camp:

- "Around 8 or 9 in the morning, the prisoners were taken from their barracks. The Germans did that and they were assembled in the square. Guards who were not on patrol took part in it as well.

After they had been assembled, they were split up in groups of five and made to sit on the ground. After a certain number of prisoners had been assembled, they were to stand up again and forced to lower their trousers to their knees, thus preventing them from running away. These groups were led into the forest where they were shot in previously dug ditches.

The ditches mentioned above were dug in advance by the prisoners themselves – they were escorted by guards, me too. I did not know to what purpose these ditches were dug until the day the prisoners were executed. There were a number of these ditches, I do not recall the exact number. They measured about 131 to 164 feet in length and 13 to 16 feet wide.

Between 500 and 600 prisoners were executed in these ditches. This is an estimate as I have not counted the condemned. I do remember, when I walked past those ditches the second day, I saw they were completely filled up with corpses and garbage."

Van Eupen, who had also participated in the deportation of Jews from the Warsaw ghetto in January 1943, was killed on December 14, 1944 in Jedrzejow in fights against partisans.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

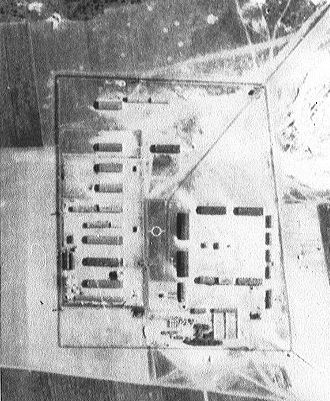

Images

Lay out of Treblinka I. Source: http://www.deathcamps.org.

Lay out of Treblinka I. Source: http://www.deathcamps.org.Extermination camp Treblinka II

Treblinka I however was only the "prologue" to Treblinka II, the actual murder factory. Extermination camp Treblinka II was established a few miles from Treblinka I. The site was not chosen at random: the area was scarcely populated and thickly wooded. Moreover, it was conveniently situated near the railway between Malkinia and Siedlce. A track was laid between Treblinka I and II as well.

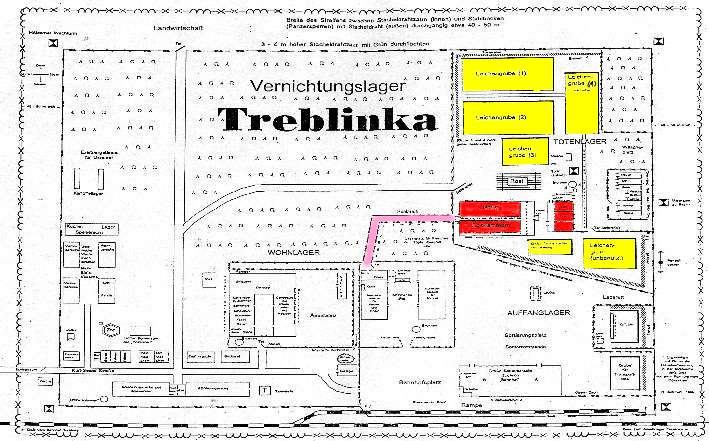

The camp was constructed in connection with Aktion Reinhard, the code name for the operation intended to exterminate the approximately 2 million Jews living in the General Government in Poland. Construction of the camp started in May-June 1942 and was partially done by inmates of Treblinka I. In charge of construction was SS-Hauptsturmführer Richard Thomalia, the architect of Aktion Reinhard. The camp took the form of a rectangle, measuring 400 by 600 yards, surrounded by a thick barbed wire fence. Watchtowers, 26 feet high were erected along the perimeter and on the corners. Fir branches were woven into and between the barbed wire, blocking all view on what was happening inside. Later on, a second fence was put up, consisting of barbed wire and anti-tank barriers.

During the construction of Treblinka II, the experience gained during the previous construction of the extermination camps Belzec and Camp Sobibor was put to good use. Therefore the camp of Treblinka was considered the most efficient extermination camp of Aktion Reinhard.

The camp was equal in size to the one in Sobibor and was divided into three large sections: the Wohngebiet (living area), the Auffanglager (reception camp) and the Totenlager (death camp). All these sections were separated by barbed wire. The barracks of the SS and the Ukrainian guards were in the living area. An office, a sick bay, storehouses and workshops were situated here also. There even was a small zoo. The Jewish laborers (Arbeitsjuden) who were selected to cooperate in the mass murder in the camp, were also housed here. Finally there were a few workshops and a parade ground where roll call was held twice a day. The square was also used for sporting events thought up by SS-Untersturmführer Kurt Franz, like boxing and running which inevitably ended in the death of the loser. Like in other camps, prisoners were punished and executed here.

The reception camp had the same function as the reception area in Belzec and Sobibor. The Jews arrived here, men, women and little children were separated from each other and their possessions taken away from them. The so-called hospital, the Lazarett, complete with a Red Cross flag lay in this part as well. Here the elderly and the sick were executed immediately after arrival. The Wohngebiet and the Auffanglager together made up the Unteres Lager (lower camp).

The Oberes Lager (upper camp) consisted of the Totenlager only, the part of the camp were the gas chambers and mass graves were located. Just like in Belzec and Sobibor, this part of the camp was camouflaged and from the outside it was impossible to see what was going on inside. Likewise, a narrow corridor, sometimes called the Himmelfahrtstraße (Ascension road) by the SS, connected the reception area to the Totenlager. At the entrance of this corridor, there was a sign with the text: "Zur Baderäume" (to the shower rooms). The first gas chambers in Treblinka were identical to the first chambers in Sobibor.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

Images

Organization of the camp

SS-Obersturmbannführer Irmfried Eberl, an Austrian physician who had previously been employed in the euthanasia facilities in Brandenburg and Bernburg in connection with Aktion T-4 – the systematic murder of the disabled – was in charge of Treblinka II initially. He had no experience whatsoever in managing the immense organization Treblinka II was and that soon became clear.

On July 22, 1942, the Warsaw ghetto was liquidated. From that day on until September 5, approximately 265,000 Jew were deported from Warsaw to Treblinka. About a week after the arrival of the first transports, Eberl wrote in a letter to his wife:

- "I know I have written little in the past but I could not do otherwise as the last weeks of Warsaw caused an unbelievable mayhem. Here in Treblinka a pace has set in which is simply breathtaking. If I could split myself in four and there were 100 hours in a day, then even that would not be sufficient."

In addition, tens of thousands of Jews from the Radon and Lublin districts were deported to Auschwitz from August 1942 onwards. Eberl was far from up to the immense task of organizing the extermination of such large numbers of people. Moreover, the gas chamber broke down regularly and the mass graves were insufficient for the influx of corpses. For lack of better, the SS started to shoot Jews in the reception area. The consequences soon became visible: trains containing new victims stood waiting on the platform and rotting corpses were scattered all over the camp. The situation was chaotic enough to cause Odilo Globocnik to stop the deportations to Treblinka II temporarily at the end of August 1942.

Eberl was held accountable for this chaos. He was relieved of his function and replaced by SS-Obersturmführer Franz Stangl who had earned his salt as commander of another extermination camp, Sobibor. Kurt Franz was his assistant. Stangl told about his arrival in Treblinka:

- "I drove up there with an SS driver. We could already smell it miles away. The road ran alongside the railway tracks. When we were 15 or 20 minutes away from Treblinka, we saw bodies lying alongside the tracks, first two or three, later on more and when we arrived at the station, there were hundreds of them – they just lay there – obviously for days in that heat. At the station was a train full of Jews, some dead, others still alive .. that train looked like as if it had already been there for days too. Treblinka was the most horrendous of what I have seen in the entire Third Reich. It was the Hell of Dante. The stench was indescribable. Hundreds, no thousands of bodies were lying around, decomposing, rotting."

This situation was also described by SS-Scharführer Franz Suchomel.

Stangl quickly set things straight. In order to cope with the flood of deportees, he had new gas chambers built in early October 1942 which had to cope with the future transports from Warsaw and the Radom district.

Apart from Stangl, who was commander until August 1943 when his assistant Kurt Franz succeeded him, some 20 to 30 German and Austrian SS men worked in the camp. Most of them had learned their trade in the euthanasia program. In addition, 90 to 150 so-called Trawniki men were employed in the camp; these Polish or Ukrainian civilians had been recruited for this work and had been trained in the SS camp of Trawniki. One of the most notorious among them was Ivan Marchenko, better known as Ivan the Terrible. He was one of the men responsible for the operation of the gas chambers.

Finally, the German guards forced 700 to 1,000 Jews to assist in the extermination process. They were selected from the incoming transports and deployed for all sorts of tasks. They cut branches to be attached to the fences as camouflage, they helped the prisoners undress, classified valuable goods, cleaned and emptied the gas chambers and helped cremate the corpses. Initially, they also were gassed after a short while and replaced by Jews from newly arrived transports but from September 1942 onwards, Stangl opted for more permanent Arbeitskommandos.

Distinction must be made between the Jews working in the Totenlager and those deployed in other parts of the camp. The life expectancy of the Arbeitsjuden in the Totenlager seldom exceeded two months. The other workers fared "better": they had their own barracks and were employed as masons, carpenters, shoemakers, tailors, kitchen staff and gold smiths. The SS men selected these people themselves but that did not mean they were out of danger. Richard Glazar, one of the surviving Arbeitsjuden testifies about this:

- "The entire Treblinka period can be divided in four phases. The first was the period when Eberl was in charge (before Glazar himself arrived, Edit.) The second, with Stangl in command but in the beginning of his rule, was still one of extreme arbitrariness in which an SS man could select someone for work and an hour later he could already be dead; "sent away" by another SS man. Phase three, in the spring of 1943, was relatively stable: the number of transports had decreased and the SS had learned that their relatively safe job away from the front depended on efficient camps and so they began to spare valuable workers. [ ..] There was some horrible kind of mutual interest among murderers and victims: staying alive. Finally, there was phase four, two to three months prior to the uprising of August 1943, a period of growing unsafety for the Germans while the Russians were approaching and the SS began to recognize that the outside world would come to know what had happened in Treblinka and that they were in fact individuals all bearing their own guilt.

- Sometimes six trains arrived and 20,000 people were sent to their death. Initially mostly Jews from Warsaw and the west with their riches – huge amounts of food, money and jewelry. It is unbelievable what and how much they all ate. I recall a boy, 16 years of age who said, a few weeks after his arrival, he had never fared better in his life than in Treblinka.

It is remarkable how not only the surviving Arbeitsjuden but the guards as well, drew a distinction between transports from the west and those from the east. With the east they meant countries such as the Baltic states and the Soviet Union whereas by the west, countries such as Czechoslovakia and Greece were meant. Jews from the west were much better off. They often carried lots of food and clothing which the Arbeitsjuden gratefully put to their own use. The origin of the transports was important to the guards as well. Werner Heyde, responsible for the euthanasia program Aktion T-4, recognized the possibility that western Jews could find out the truth behind the transports and offer resistance. Hence he considered it important to mislead them until the last moment when resistance was no longer possible. With Jews from the east, precautions were of less importance as they simply expected terror, as they had already often been confronted with pogroms and anti-Jewish activities during their lives. Therefore they were treated more aggressively on arrival in the camp than transports from the west. Richard Glazar, himself originating from Prague, about his arrival in Treblinka:

- "We were all standing at the windows looking out. I saw a green hedge, barracks and heard something that sounded like a farm tractor. I was in high heaven. [..] There was loud shouting, not too loud, nobody mistreated us. I followed the crowd: "men to the right, women and children to the left," so we were told. One of the SS men, - I learned his name later, Küttner – told us in a friendly voice we were going to a disinfection bath and subsequently to work.

We were not dressed in striped uniforms, filthy, devoured by vermin or almost starved to death like most prisoners in concentration camps. My own group, the Czechs and the Hofjuden were dressed very well. There was no shortage of clothing. I usually wore riding pants, a velvet coat, brown boots, a shirt, a silk tie and a sweater when it was cold. It was no coincidence that the Arbeitsjuden did their best to look well. You were very concerned about how you looked. It was extremely important to look neat at roll call. [..] The effect of looking neat did always help – it even imbued respect. But the fact you looked neat could be considered bragging or toadyism and result in a penalty or even death. In the end we understood that maximum safety lay in looking as much as possible – not too much though – like the SS men themselves."

Definitielijst

- heat

- High-explosive anti-tank warhead. Shaped charge projectile to punch through armour. Used in e.g. bazooka or in the Panzerfaust.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Images

The extermination process

Most trains consisted of 50 to 60 cars, containing a few thousand people. The train stopped first at the station of Malkinia. There, some 20 cars were uncoupled and driven to Treblinka itself. That way the guards could maintain control. In Treblinka II the Jews got off the train, assisted by the Arbeitsjuden from the Kommando Blau, also known as the Bahnhofkommando.

At the end of 1942, Stangl ordered the so-called railway station to be built. The building looked like a normal station, including counters, train schedules, signs pointing to train connections, even a clock with a painted face plate and hands that never moved. That fitted the idea to mislead the Jews as long as possible and leave them unaware of their eventual fate. They were made to believe they had arrived in a transit camp.

Arriving Jews were told they had arrived in a transit camp and that they were to take a shower and have their clothes disinfected for hygienic reasons. Men, women and children were separated from each other. The women and children were marched into the left shed, the men into the right. In these undressing barracks they were received by the Red Command. Joe Siedlecki was one of them:

- "We had to supervise the undressing in the barracks. We were to shout: ‘Ganz nackt, Schuhe zusammenbinden, Geld und Dokumente mitnehmen (completely naked, tie your shoes together, take money and documents with you). That way the people were kept ignorant. They thought they were going to take a bath and would be deloused and that they could keep their money and documents for their own safety. That put them at ease. In a later phase, the men had to undress outside. Their shed was used as an assembly depot for goods. The women continued undressing inside. There, their hair was shaved off as well."

The elderly, the sick, the wounded and others too weak were taken to the Lazarett immediately because they would slow the extermination process down too much. This building, disguised as a hospital, was nothing less than an execution site. The victims were to undress and sit on the rim of a cremation pit and shot. Their bodies were cremated on the spot.

From the dressing rooms, a path led directly to the gas chambers. This path, the Schlauch (hose) was fenced in with barbed wire and heavily camouflaged. The SS called this path cynically the Himmelfahrtstraße (Ascension road). The extermination zone measured 200 by 250 yards and was located in the southeastern part of the camp. It was completely sealed off from the outside world with an earthen embankment and surrounded by barbed wire. Initially, there were only three gas chambers. After Stangl’s arrival, 10 new chambers were built. An engine, providing the toxic carbon monoxide that was fed into the chambers through tubes, stood in an adjoining shed. Treblinka II did not make use of Zyklon-B.

The deportees were rushed through the Schlauch naked. Meanwhile, Arbeitsjuden classified the clothing and possessions left behind in the dressing rooms. These possessions were sorted and sent back to Germany from the SS depots in Lublin.

After all prisoners had entered the so-called shower room, the doors were locked and sealed. The nearby engine was started and blew the toxic carbon monoxide gas into the chamber. In about 30 minutes all occupants were dead. In the early stage, some 2,000 Jews could be gassed within three to four hours. Later on, in particular after the ten new gas chambers had become operational, the whole procedure was completed in an hour and a half.

Two to three hundred Jews worked in the Totenlager. They made up the Sonderkommando, tasked with emptying the gas chambers and dragging the bodies to the pits. They also extracted gold teeth and molars from the dead. Initially, the corpses were buried in mass graves but from the winter of 1942-1943 onwards, these graves were opened and the remains cremated. In the spring of 1943, a new method of cremation was tested. Two enormous grates, made from train rails and called roasting spits, were installed. On each grate, dozens of corpses could be cremated simultaneously. Cremation of corpses matched Aktion 1005, the operation in which the Germans attempted to erase all traces of the mass murder.

The extermination program in Treblinka II started on July 23, 1942; in May 1943, the last transports arrived although afterwards, for some isolated transports Treblinka was still the final destination. Between July and September 1942, some 265,000 Jews from the Warsaw ghetto arrived in Treblinka II. Between August and November, some 346,000 Polish Jews from the Radom district arrived along with 33,000 Jews from Lublin. In October Theresienstadt was being evacuated and five transports brought 8,000 people to Treblinka II. In the same period, the deportation of over 100,000 Jews from the Biyalistok district started. Furthermore, transports arrived from countries like Greece, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Slovakia and Romenia.

It is impossible to say exactly how many people have been murdered. The so-called Höfle telegram, discovered in 2000, gives an idea. This document, sent by SS-Sturmbannführer Hermann Höfle, was a message to SS-Oberststurmbannführer Adolf Eichmann and SS-Oberststurmbannführer Heim in Krakow. It contained an overview of transports up to December 31, 1942 to the extermination camps of Aktion Reinhard. As to Treblinka, it mentioned 731,555 Jews deported and gassed. After that date, Treblinka II remained operational for a little over six months but did not receive as many transports as it in 1942. Today, the number of Jews and non-Jews who have been murdered is estimated at between 870,000 and 925,000.

Definitielijst

- Aktion 1005

- German secret operation to cover up the traces of mass extermination in the east. The bodies of the victims of the Einsatzgruppen and extermination camps were dug up from the mass graves and then burned. The operation was under command of SS-Standartenführer Paul Blobel.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Theresienstadt

- City in the Czech Republic. Here the Nazis established a model concentration camp.

- Zyklon-B

- Poison gas that was systematically used in German extermination camps, primarily to murder Jews.

Images

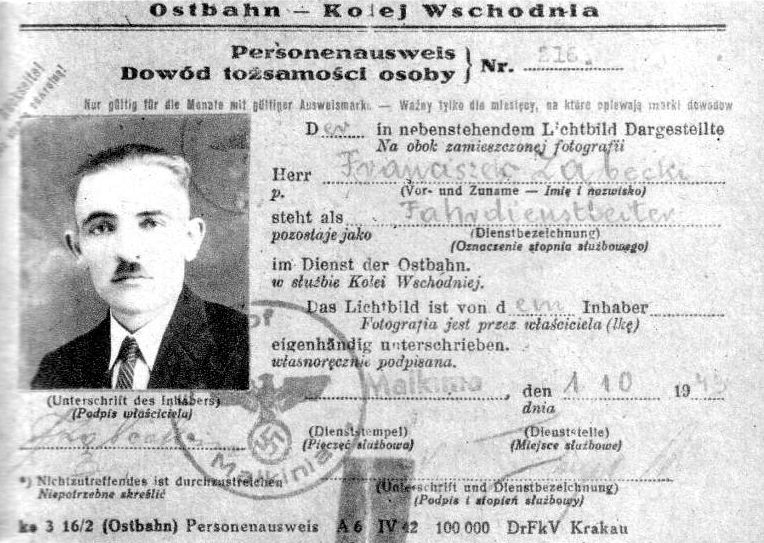

Station master Franz Zabecki witnessed many trains carrying victms on their way to the extermination camp.

Station master Franz Zabecki witnessed many trains carrying victms on their way to the extermination camp.  Human remains found in Treblinka. Source: http://www.deathcamps.org.

Human remains found in Treblinka. Source: http://www.deathcamps.org.Resistance

Initially, organized resistance in Treblinka did not exist. There were however some individual acts of resistance and attempts at escape.

The first known action was the murder of SS man Max Biala. He was stabbed to death on September 11, 1942 by Meir Berliner, one of the Arbeitsjuden who had arrived from Warsaw a few days earlier. The other guards immediately opened fire, killing Berliner and 10 other prisoners. When the situation was back under control another roll call was held. 10 prisoners were taken out of the mass at random and executed. The day after, during morning roll call, 150 prisoners were taken to the Lazarett and executed. That way, the guards wanted to imbue so much fear, the others would not emulate Berliner’s example.

After this occurrence, the guards found it wiser to keep the Arbeitsjuden "in service" longer and not kill them after a few days which was the usual procedure up to then. In doing so, they hoped such individual desperate attempts would not be made again.

People did try to escape from Treblinka though, in particular during the first months. Some succeeded, others were caught. Exact figures as to how many did escape do not exist. In any case, a few have played an important role after their escape. David Nowodworski, Avraham (Jacob) Krzepicki and Lazar Szerszein managed to reach Warsaw after their escape where they, as members of the Zydowska Organizacja Bojowa (Jewish armed organization) took part in the uprising of the Warsaw ghetto. In December 1942, two members of the Bahnhofkommando attempted to escape. They were caught however and shot by Kurt Franz himself. At a special roll call, Franz announced he would from then on execute 10 others for each attempt at escape. Yet, Jews still tried to escape. It became increasingly more difficult though as security measures were tightened steadily.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

The uprising of August 2, 1943

The best known act of resistance occurred in August 1943. Preparations were started in January of that year. "Mid-January, everything changed," Richard Glazar tells. "This was the beginning of phase three: less transports and so less food and no new clothing. That was the time the plans for the uprising were drafted." The prisoners understood the camp would not exist much longer: the number of transports had dropped sharply; the major part of the stolen possessions had been sorted and shipped to Germany; most of the corpses had been burned. In that period, a typhoid epidemic also erupted which claimed quite a lot of victims, in combination with the famine.

Everything pointed to one thing: the camp would not be in service much longer. The Jews still remaining knew they would be liquidated along with the camp. "There was nothing left in the depots. Everything had been packed and shipped. There was no food anymore. You can imagine how we felt. You see, those items justified our existence in Treblinka. If there was nothing to classify and to ship, for what reason would they keep us alive?" The plan to organize a massive uprising was born.

An organization committee was formed, consisting of Dr. Iliya Chorazycki, Zeev Kurland, the kapo of the Lazarett Zjelo Bloch, a lieutenant from the Czech army and Moshe Lubling. First of all, it was necessary to acquire arms. They hoped they could persuade Ukrainian guards to provide them with weapons. The Jews in the camp, in particular the so-called Goldjuden, responsible for collecting and sorting the money, gold, silver and other valuable items of the deportees, kept part of those riches for themselves. Guards who provided them with food for instance were being paid with this. Now they intended to use those riches to buy arms. They had to go about it very cautiously, lest the Germans would get suspicious.

Moshe Lubling, one of the Goldjuden, attempted to bribe a Ukrainian guard he knew in giving him a pistol. The guard did take the money but never provided the weapon. This and some other similar setbacks forced the Jews to look for another solution. The most logical, it seemed to them, was to steal weapons and munitions from the arsenal in the camp. Here, they had a stroke of luck: a Jewish locksmith was ordered to repair the lock of the arsenal which he did but he also managed to make a duplicate of the key which could be used by the resistance people.

After this lucky break, in March 1943, the resistance committee suffered a serious setback. Glazar tells:

- "Küttner smelled a rat – I cannot say it otherwise. He assumed something was brewing and with totally instinctive flair, he selected the one man who was irreplaceable to us: Zjelo Bloch, the military expert of the committee. Küttner used the pretext that some clothes were missing and Zjelo was held responsible. [..] Zjelo was sent to Lager II."

- "The evening he left, all hope evaporated for us. I remember that night very clearly. It was the only time we almost lost our minds, that we voiced our emotions. That could have spelled the end for us."

Despite this enormous setback, preparations continued: Rudi Masarek, a young Czech, took charge of the military department. Various combat units were formed and Chorazycki designed a plan of attack that would be carried out on April 21. Before it came to that however, Chorazycki had an argument with Kurt Franz – the reason is not entirely clear - and he attacked the German with a knife. He did not succeed in maiming or killing Franz but he was lucky enough to take poison and so sacrifice his life.

These two setbacks caused the plans for the uprising to be postponed. The depleted organization committee risked being idle altogether. Between May and June 1943, some new energetic members joined the resistance, including Rudeck Lubernicki and camp eldest (kapo) Marcell Galewski. The committee got a new lease on life and the number of resistance fighters, including many kapo’s, increased. Jankiel Wiernik played an important role. He was the only prisoner who was allowed to enter both the upper and lower camp, thanks to his capabilities as a carpenter. As Bloch still worked in the upper camp, Wiernik was able to maintain contact between the two factions. On the evening of the uprising itself, some 60 Jews would participate in the resistance.

In July 1943, it became really clear the end of the camp was near. Most corpses had been burned and the SS had thrown a party to celebrate the end of their task. Therefore the organization committee set the date for the uprising at August 2. The uprising was scheduled for the late afternoon to offer the prisoners the best chance of escape in the dark. It had to be done during the day however as the guards would not be in their quarters then. Capturing weapons was an essential element in the plan and the arsenal was close to the SS quarters. That day, they were lucky: Kurt Franz and some 20 guards were not in the camp. This seriously weakened the guarding of the camp.

Shortly after noon, they managed to enter the arsenal unnoticed and steal weapons and grenades. During the next few hours, these were distributed among the various groups. Up to about 15:30, everything went according to plan but then, SS man Küttner caught a young Jew with money in his pocket. He started to interrogate him harshly. The resistance committee was informed about this and they feared the boy might probably betray something about the imminent uprising. Therefore they gave the signal to eliminate Küttner and immediately start phase two of the uprising: attacking the guards and destroying the camp. Glazer tells:

- "My clearest memory of the uprising was one huge chaos. The first moments were extremely exciting; hand grenades and bottles of petrol exploding everywhere, there was fire all around and shooting from all sides. Everything went contrary to plan and so the confusion was massive."

The organization committee had lost control of the situation. While the resistance fighters kept firing at the guards, prisoners everywhere tried to break through the fence and reach the nearby forest. Many of them were killed or wounded as the guards in the watchtowers opened fire on them. The firefight did not last long however. As the uprising had erupted earlier as planned the Jews had been unable to steal and distribute sufficient arms and ammunition.

At the time of the uprising, there were some 850 Arbeitsjuden in the camp. More than half of them were killed while escaping. About a hundred prisoners did not make any attempt at escape at all and remained in the camp. At least as many of them managed to escape. That did not mean at all they were safe. It was a long way to run from the camp to the nearby forest. In addition, they hardly received any assistance from the local population, if at all. Many escapees were captured hours after their escape. Camp commander Franz Stangl left no doubt about their fate: "They were shot on the spot. During the evening, the numbers were coming in. Someone was at the phone and added them up. At 18:00 it looked like 40 more had been captured than there had ever been in the camp. I thought ‘My God, they are going to shoot the Polskis too as they were firing at anything that moved."

Only a very few managed to stay out of Nazi hands. The exact number is unknown but it is estimated some 40 of them also survived the war. They gave important testimony about the operation of and life in the camp. Among them Abraham Bomba, Richard Glazar, Moshe Rappaport and others.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- kapo

- A Kapo was a prisoner in a concentration camp in Nazi Germany during World War 2 who was assigned to supervise other prisoners. A Kapo had to supervise the work of the prisoners and was responsible for their results on behalf of the SS.

- Mid

- Military intelligence service.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

The end and the Treblinka trials

After the uprising, a few transports still arrived in Treblinka. The extermination facilities had come through the uprising virtually undamaged. On August 18 and 19, 1943, another two trains arrived with Jews from Biyalistok. Shortly afterwards, the buildings were blown up, trees were planted on the premises and a small farm was built. Globocnik confirms this: "In order for a guard to carry out his task, a small farm was built on the premises and it will be inhabited by an expert, who will have to receive a steady income in order to maintain the farm." This "expert," a Ukrainian, lived there with his family until the Soviets occupied the area. This way, the Nazis hoped to prevent everything that had happened in Treblinka from becoming public knowledge.

On October 20, a train consisting of five cars left Treblinka with the last Jews on board. They were taken to Sobibor and killed immediately. About 25 prisoners stayed behind in the camp where they were executed a few days later. Shortly after, the last guards left Treblinka II.

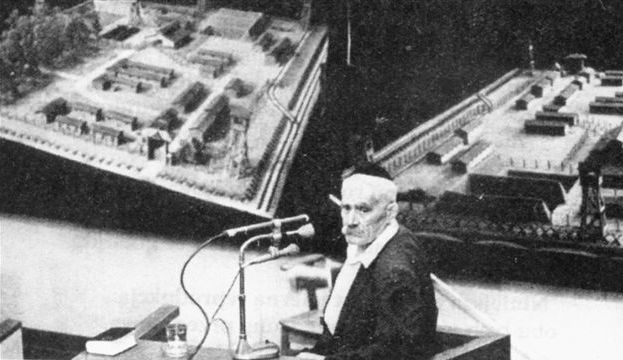

After the war, three trials were held in Germany pertaining to the mass murders in Treblinka. The first public hearing was that of Joseph (Sepp) Hirtreiter. He was sentenced to life imprisonment. The second hearing was that of 10 SS officers who had served in Treblinka II. The most important defendant was Kurt Franz. He was also sentenced to life. The rest was sentenced to a maximum of 12 years with the exception of one defendant who was acquitted. The third trial was that of Franz Stangl, second commander of Treblinka. Stangl was arrested in Brazil as late as the sixties and extradited to Germany. After a trial lasting six months, he was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1971. He died in prison in June that same year.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

Images

National monument Treblinka

It took until 1964 before Treblinka became a national monument. Because little remains of the original extermination camp, an attempt was made to let the camp relive in granite. A symbolic railway was laid with sleepers of granite. The fences and the watchtowers are also depicted in granite.

A large column now stands on the spot where the gas chambers used to be. It rises up from the center of a symbolic burial site containing 17,000 stones with the names of villages, cities and countries engraved on them whose Jewish inhabitants have been murdered in Treblinka. The pits in which the corpses were cremated are depicted by a material that resembles solidified tar.

Images

Information

- Article by:

- Gerd Van der Auwera

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 04-11-2017

- Last edit on:

- 05-03-2021

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- ARAD, Y., Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, Indiana University Press, Bloomington (USA), 1999.

- ECK, L. VAN, Het boek der kampen, Kritak, Leuven, 1978.

- REES, L., Auschwitz, Anthos, Amsterdam, 2005.

- SERENY, G., Into that darkness, McGraw-Hill, 1974.

- WISTRICH, R.S., Who's who in Nazi Germany, Routledge, Londen, 2002.

- Treblinka I

- Labour Camp Treblinka I

- Extermination camp Treblinka I (wikipedia)

- Vernichtunslager Treblinka I (wikipedia)

- Death Camps

- Jewish Virtual Library

- Chronology Treblinka

- Treblinka (USHMM)

- Nizkor

- Getuigenis Samuel Rasjman

- Interview met Franz Suchomel