Introduction

When the Nazis began the final evacuation of the Warsaw ghetto on 19 April 1943, they met with fierce resistance. Jewish men and women had armed themselves and formed a fighting squad. They wanted to take revenge against the Germans who had deported their family members to the Treblinka extermination camp in the previous months. This time they decided that they would not be slaughtered without putting up a fight.

Although the Germans had expected some resistance, they expected to expel all remaining Jews from the ghetto within three days. However, it was not until May 16, 1943 that Jürgen Stroop, the German commander in charge of the evacuation, was able to report to his superiors that his operation had succeeded. Even after that time, there was still talk of Jewish resistance in the former Warsaw ghetto.

This article describes the uprising and the elimination of the Warsaw ghetto. Much attention is given to the processes and events which resulted in the final fights in the spring of 1943. The armed resistance did not emerge overnight, but it was a result of a gradual process that began with the very creation of the ghetto in the fall of 1940. This is why we will begin this article with the establishment of the ghetto.

Definitielijst

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

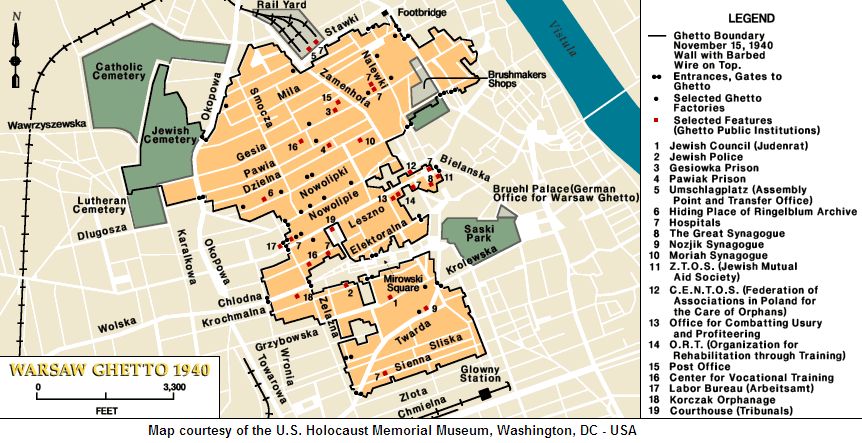

The ghetto

On 2 October 1940, the Warsaw Jews were informed of the establishment of the ghetto by order of Ludwig Fischer, Warsaw’s district governor. This would be the place where the Jewish inhabitants of Warsaw and nearby surroundings would be concentrated, locked away from the outside world. Two years before, on 12 November 1938, during a meeting of Ministry of Aviation, Reinhard Heydrich, the man responsible for the Nazi Party's approach to the Jewish question, spoke against the establishment of the ghetto. "We will not be able to control a ghetto where only Jews would be housed. It would be a permanent hideaway for criminals and a breeding place for epidemics and such." When Heydrich presented his view on the Jewish question, the war had not started yet, and it was believed that the Jews could be forcibly expelled from Germany.

In October of 1940 the situation had, however, changed. The war had started about one year before, and Germany was now occupying a large part of Europe. As a result of invading Poland, the numbers of Jews on the German territory had grown vastly. The plan to get rid of the Jews by forcing them to emigrate had failed due to the war situation. This is why many of the ghettos were established, mostly on the initiative of local Nazi governors. The first ghetto was established in October 1939 in the city of Piotrków Trybunalski. State safety was pointed out as the reason for closing the Jews in a ghetto; the Jews were after all seen as the number one enemy in Nazi Germany. Another reason was that the Jews were supposedly spreading diseases and, therefore, had to be quarantined. Both reasons were closely related to the anti-Semitic propaganda of the Nazi party. The ghettos became an important feature of the German extermination policy. Large numbers of Jews died in the ghettos due to poor living and working conditions. At the later stage, the concentration of the Jewish community in the closed ghettos made the mass deportations to the extermination camps easier.

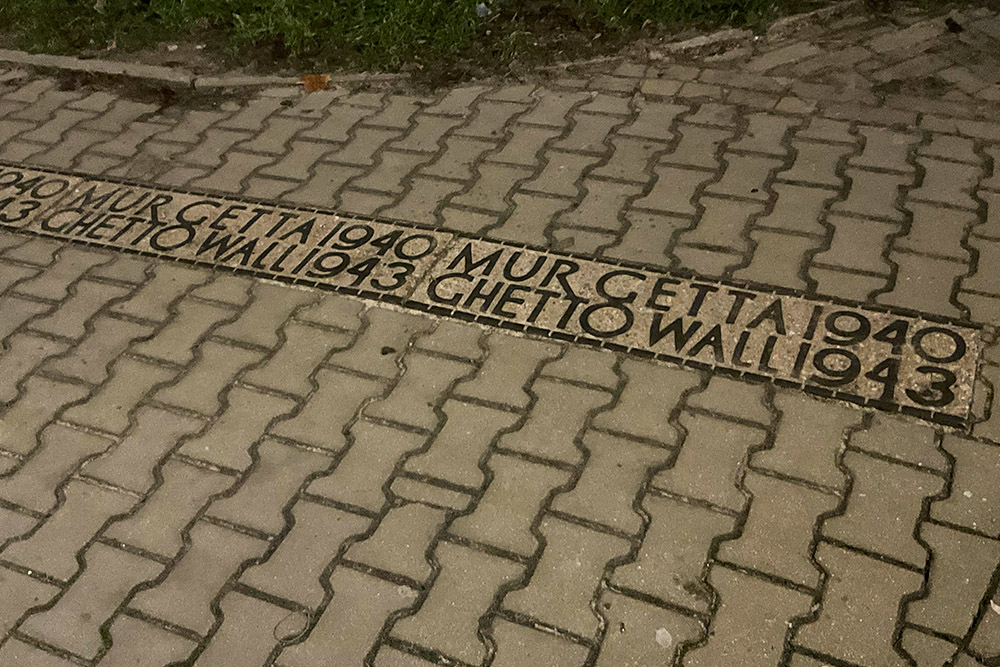

The Warsaw ghetto was the largest ghetto created by Germans. A part of the city was encircled by a 3-meter high stone wall with circumference of 16 kilometers. Approximately 80,000 non-Jewish Poles had to leave the area first. Then 140,000 Jews residing elsewhere in the city were transferred to the ghetto where another 240,000 Jews had been already placed. At its peak, approximately 445,000 Jews lived in the ghetto. This isolated area included not only the houses of the ghetto residents, but also many workhouses, which were owned by German industrialists and supervised by the Wehrmacht. The Jews were working there as forced labourers for the German war industry.

On 16 November 1940 the ghetto was completely closed off from the outside world. Contact with the Germans was possible through a 24-member Jewish Council under the leadership of Adam Czerniakow. The Jewish Council was responsible for the distribution of food, among other things. The food was not nearly sufficient. For example, in the second half of 1941, the ghetto residents were being given food rations of approximately 184 calories per day, while Germans were being provided with food of approximately 2,310 calories. Moreover, the average price of 1 calorie was 5.9 z³oty for Jews, while it was only 0.3 z³oty for the Germans. A small number of more powerful Jews had managed to access through the black market far more food than was provided to the rest. The first victims of malnutrition were thus mostly lower-class Jews without work. During the first year, more than 43,000 people died in the ghetto, and during the first nine months of 1942, there were about 37,000 more. They were dying not only due to malnutrition, but also because of the diseases that broke out as a result of the unhealthy living conditions and lack of medical care.

Definitielijst

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Seed of the resistance

In spite of the miserable living conditions in the ghetto, the Jewish underground groups were organizing many political, educational and cultural activities. Illegal publications were printed, and courses, trainings and music performances were given. Writers, poets and historians also continued to work illegally. The emerging underground organizations were rooted in various political parties and in the Zionist youth movements. Many attempts were made to establish cooperation among the organizations, but they failed because the ideological differences among various movements were too great. There was also lack of mutual trust. However, some of the organizations united within the Anti-Fascist Bloc. One of these organizations was Mordechai Anielewicz's left-Zionist youth movement, Hashomer Hatzair. The Anti-Fascist Bloc had established a combat organization that resisted not only the Germans, but also the members of the Jewish Council and the Jewish police – the loathed Order Service – whose members were considered traitors of their own people. They had also established contacts with Polish resistance outside of the ghetto and with resistance fighters in other ghetto's.

Much to the dislike of the Jewish Council that opted for obedience to the Germans, the Anti-Fascist Bloc published pamphlets calling on the Jewish population to resist. They also informed them about the activities of the Polish resistance movement and the general course of the war. For example, news reached the ghetto that Reinhard Heydrich had died on 4 June 4 1942 as a result of an attack by Czech resistance fighters. Thanks to the efforts of the Anti-Fascist Association, the resistance among the Warsaw ghetto's population slowly began to grow. More often than not, the Jewish police were met with resistance, and the hospital personnel and the workers in the workshops went on strike.

The German authorities were soon informed of the illegal activity in the ghetto. Their reaction was severe. In April and May 1942, several round-ups were organized, and the ghetto was shaken by collective murders. With the help of the Jewish collaborators, the SS arrested or murdered many of the intellectuals and resistance fighters, among them the leaders of the Anti-Fascist Bloc. It was only on the eve of the mass deportations to the Treblinka extermination camp that the Anti-Fascist Bloc had been eliminated. The seed of resistance had however been planted.

Definitielijst

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Deportations

In the spring of 1942, Operation Reinhard began. The goal of this secret operation was a complete elimination of the Jews in the Generalgouvernement, a part of Poland which had not been annexed by the Germany, but was still under the German rule. The ghettos had been evacuated and all the Jews (with the temporary exception of forced labourers in the concentration camps) were to be killed in the gas chambers of the Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka extermination camps. The evacuation of the Warsaw ghetto began on 22 July 1942. Despite the fact that the ghetto population had risen to 445,000 in the beginning of 1941, the mortality rate was so high that only about 350,000 Jews still remained in the ghetto when the deportations started. The evacuation was led by SS-Sturmbannführer Hermann Höfle, the chief of Operation Reinhard. On the morning of 22 July 1942 he informed Adam Czerniakow that the Jewish Council would be responsible for a daily delivery of 6,000 Jews to the Umslagplatz, from where the trains to Treblinka would depart. Although it was not shared that the Jews would be murdered, Czerniakow probably knew it anyway. In any case, he committed suicide on 24 July, as he could not bear responsibility for the deportations. He was succeeded by Marek Lichtenbaum.

Adam Czerniakow, leader of the Jewish counsel posing with some inhabitants of the ghetto. Source: USHMM

According to Jürgen Stroop's report from May 1943, "310,322 Jews had been resettled" [ausgesiedelt] in the period between 22 July and 3 October 1942, after the ghetto had been entirely liquidated. "Resettling" was a euphemism for mass murder, because an estimated 254.000 of these Jews arrived between 22 July and 21 September 1942 in the Treblinka extermination camp to be murdered there. The remaining 310,322 Jews were killed in the ghetto or were sent to work camps. The deportations proceeded without major issues. There were apparently not many Jews who would voluntarily register themselves at the Umslagplatz, but some gave in when a promise was made that everyone coming on their own accord between 29 and 31 July would receive a travel ration of 3 kg of bread and 1 kg of jam. There were, however, not enough Jews that registered voluntarily, and the German authorities reacted with violence. Housing units and sometimes even whole streets were closed off by the German troops, and the police agents would catch everybody without a work pass. Only the work pass could temporarily delay the deportation. People caught by the police were then brought to the Umschlagplatz in trucks.

German and Polish troops were assisted throughout the evacuation of the ghetto by the members of the Order Service. Thanks to their collaboration, these members were temporarily exempted from the deportations, but it led to great indignation within the Jewish community. On 20 August 1942 a resistance fighter had unsuccessfully attempted to assassinate Józef Szeryński, the Jewish police commandant. Pamphlets were printed where the members of the Jewish police were accused of collaborating in murder. Many times, Jews would individually or in small groups resist the arrests by the Germans or the Jewish police. German workshops in the ghetto were also set on fire. However, this small-scale resistance had hardly any effect on the deportations, and it was met with substantial violence. Jews who were active in resistance, were killed on the spot. Among them were also the members of the Anti-Fascist Block, which was by then already severely weakened. After the provisional final transport of 2,200 Jews, including the policemen and their families, had left for Treblinka, some 55,000 to 60,000 Jews were still living in the remaining parts of the ghetto. These were mainly young Jews working in the ghetto in German workshops or those who managed to hide.

Why was there no well-organized resistance on a large scale during the first wave of deportations? There are several reasons for this. One of them was that many Jews had little faith in the rumors about their actual final destination. It was beyond their imagination that they would all be murdered in the gas chambers. This was partly due to the German policy of denial and deception. Shortly before the deportations, the schools were all of a sudden allowed to open, the performance of the Jewish workers in the German workshops was praised, and it was in no way shown that the inhabitants of the ghetto were in great danger. When the deportations began, this charade was continued by promising the Jews extra food if they would voluntarily register for the deportations. The actual final destination of the transports was also kept secret by telling the Jews that they would be relocated to the labour camps in the East. The Jewish Council consciously or unconsciously helped to maintain this policy of deception. They labeled the rumors about the mass killings as dangerous and ridiculous. An eyewitness account by a Jewish escapee from Treblinka was not recognized by the Jewish Council and was even considered a provocation by Jacob Lejkin, Józef Szeryński’s successor as the commander of the Jewish Order Service.

Other reasons for the lack of large-scale organized resistance included a shortage of weapons and the heavy blows being inflicted on the Jewish resistance in the spring of 1942. However, the first wave of deportations went on without bigger issues for the Nazis. This period’s terror of deportations formed a background for establishing the Jewish Combat Organization, the most important resistance organization in the uprising of April and May 1943.

Definitielijst

- collaboration

- Cooperation of the people with the occupying forces, more generally spoken the term for individuals who cooperate with the occupying force is collaborator.

- Generalgouvernement

- That part of Polish territory occupied by the Germans in 1939. It was an autonomous part of Greater Germany. In August 1941 Eastern Galicia was added to the Generalgouvernement. It was governed solely by Germans under direction of Generalgouverneur Hans Frank. It was to become a full German province inhabited only by German colonists.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Jewish Combat Organization (ZOB)

In the autumn of 1942, a psychological change resulting from the summer's deportation wave was already visible among the ghetto residents. The willingness to resist had grown as the remaining Jews lost many of their family members. Meanwhile, there was much more certainty about the true final destination of the deportations, and most ghetto residents no longer believed in the Germans' lies or in the denial of the Jewish Council.

The number of rumours about the true purpose of the deportations had grown since August and September 1942. The most convincing were the reports of the Jews who managed to escape from Treblinka and returned to the ghetto. One of them was a journalist, Jacob Rabinowicz, who wrote a report about the extermination in Treblinka. The Jewish resistance managed to verify this report by setting up a meeting with Azriel Wallach, another Jew who escaped from an extermination camp and was staying in Soko³ów Podlaski. More escapees arrived in Warsaw and told the same story. There was no more doubt that the Jews were being eradicated in Treblinka, and the ghetto residents also felt their own end nearing.

Those who remained in the ghetto felt responsible for not having done enough to save their families. "No matter with whom you talked, everyone kept repeating the same thing: we should have not allowed the deportation," wrote a ghetto resident and historian Emanuel Ringelblum on 5 November 1942. "We should have gone to the streets, set everything on fire, barged through the walls to get to the other side." The Germans would retaliate, it would have cost tens of thousands victims, but not 300,000. Our apathy did not get us anywhere. This should not happen again. Now we must resist, we must do everything to defend ourselves against the enemy." Not everybody shared the same view, however, as the decision to engage in organized resistance emerged only slowly. "The religious Jews were against it", said Marek Edelmann who fought in the revolt of April and May 1943. "They kept saying: God wants it, so be it."

In the months following the first wave of deportations, the news of the developments at the front further fueled the resistance. On 23 August 1942 the Battle of Stalingrad began, and it lasted until February 1943, resulting in a German defeat. Also during the Battle of El Alamein in North Africa the Germans suffered heavy losses. In November 1942 this battle was won by Bernard Montgomery's 8th Army. Both of these German defeats marked a turning point in the war in favour of the Allies. At the same time, the news of increased activity of the Polish resistance had a positive influence on the morale of the ghetto resistance fighters. The German occupiers also admitted that the security situation in Poland had deteriorated as a result.

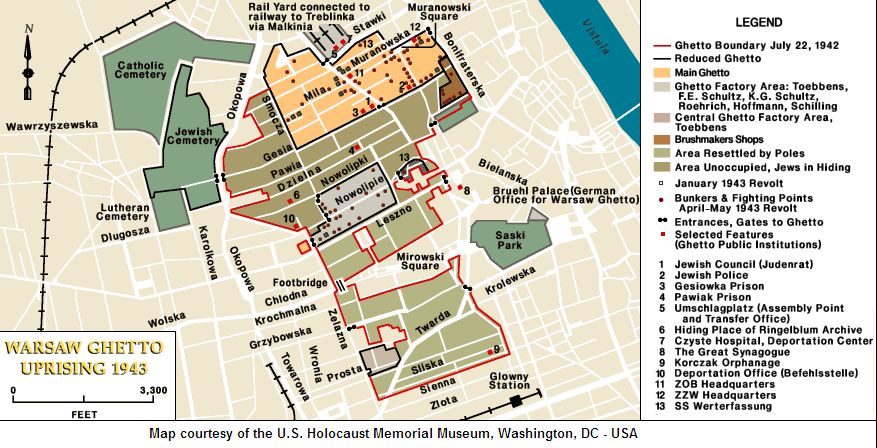

Because of the aforementioned psychological change and the resulting increased will to resist, cooperation among various Jewish resistance groups finally occurred in the autumn of 1942. They united in the Jewish Combat Organization (¯ydowska Organizacja Bojowa, ¯OB). This organization had been established on 28 July 1942, shortly after the first deportations to Treblinka had started, and it was led by Mordechai Anielewicz. ¯OB was the successor of the Anti-Fascist Bloc that fell apart after the arrests of many of the organization's members.

In July 1942, the ¯OB consisted of only three Zionist youth movements, and the efforts to persuade other resistance and political groups to collaborate failed at that time. In October and November 1942, however, this had changed, and other resistance groups joined the organization. The only Zionist movement that did not collaborate was the so-called Revisionists, who decided to join the Jewish Military Union (¯ydowski Zwi±zek Wojskowy, ¯ZW) instead. This organization consisted mainly of Jewish ex-military men and partisans who had returned to the ghetto. Attempts to integrate the Jewish Military Union into the larger Jewish Confederation failed. During the revolt in April and May 1943, both groups fought together against the Germans, despite their mutual struggles.

The main objective of the ¯OB was "to defend the Jewish population of Warsaw against the extermination action of the occupiers and to protect them from traitors and agents working with the occupiers." In practice, this meant not only preparing for an uprising against the Germans, but also trying to eliminate members of the Jewish Council and the Order Service. On 29 October the leader of the Order Service, Jacob Lejkin, was liquidated by the ¯OB. One month later, the hated leader of the Jewish Council's economy division was assassinated. The archives of Emanuel Ringelblum contain the names of thirteen people assassinated by the Jewish Combat Organization (¯OB).

In the period until 18 January 1943, ¯OB continued to engage in and maintain contacts with the Polish resistance, to educate and train troops, and to collect weapons. The latter was especially difficult, as the Polish Home Army (Armia Krajowa), the largest militarized resistance movement in Poland, reacted to requests for weapons with suspicion and great restraint. "Various groups of Jews, among them communists, have recently appealed to us and begged for weapons, as if our arsenals were fully equipped", wrote general Stefan Rowecki, the commandant of the Polish Home Army in a message from 4 January 1943 to the Polish government in exile in London. "On a trial basis, I offered them a few pistols. I wonder if they would make any use of these weapons. More I cannot give them, as we ourselves don't have many, as you surely know." This shortage of weapons was not a lie and it was indeed one of the weaknesses of the Home Army during the Polish uprising in Warsaw in August 1944. The limited amount of weapons made available by the Polish resistance was supplemented by weapons, ammunition and explosives purchased on the black market. People made their own grenades, Molotov cocktails and mines in specially equipped workshops in the ghetto. Thanks to these efforts, the Jewish Combat Organization was able to battle the enemy for the very first time on 18 January 1943 -- the day that the Germans wanted to resume deportations to Treblinka.

Definitielijst

- El Alamein

- City in North Egypt. The Battle of El Alamein took place from October to November 1942 and was a turning point in the war. The German-Italian advance in North Africa was finally halted by the Allies.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Januar Aktion

On 9 January 1943 the Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler visited the Warsaw ghetto. He noticed that there were still 32,000 ghetto residents working in privately-owned and Wehrmacht workshops and factories, while he had ordered all the Jews working in the war industry within the Generalgouvernement to be housed in the SS concentration camps. There they should continue their work under the leadership of the SS-Wirtschafts- und Verwaltungshauptamt (SS-WVHA), the economic headquarters of the SS led by Oswald Pohl. This was only a temporary solution, since the ultimate goal of Aktion Reinhard was to make the Generalgouvernement completely free of Jews. That is why Himmler, encouraged by the critical security situation in Poland, ordered the rapid liquidation of the ghetto. First of all, an order was given to pick up 8.000 Jews without a working pass and to deport them to Treblinka. This action was led by SS-Oberführer Ferdinand von Sammern-Frankenegg, the SS und Polizeiführer of Warsaw, from 22 July 1942 until 19 April 1943.

The ŻOB planned an uprising that should have started on 22 January, but the Germans were just one step ahead of them. Nevertheless, when the German troops arrived in the ghetto on 18 January 1942 to carry out their assignment, they were met with fierce resistance. Although the workshop directors had been instructed to send their Jewish workers to the Umschlagplatz, only a few had reported here. Even the Jewish policemen refused to cooperate in the deportation this time, risking their lives and those of their families. The majority of the ghetto inhabitants had hidden, and the Nazis failed to find 8,000 Jews without a working pass. Only after a few hours had 1,000 people gathered on the Umschlagplatz. While the Germans began their raid, the Jewish Combat Organization distributed pamphlets calling for resistance. "Don't go willingly to die Defend yourself! Take an axe, a knife in your hand, barricade your house. (...) Fight!" Meanwhile, Jewish fighters attacked German troops.

"The Jewish population received [the Germans] with grenades and revolver bullets, stones and caustic soda", wrote the underground newspaper Głos Warszawy (The Voice of Warsaw) on 19 January 1943. "The machine guns and the explosions resound uninterruptedly. [...] The German cruelties know no boundaries! Death to the fascist murderers!" The Germans were completely surprised by the attacks of Jewish fighting troops coming on them from cellars, attics and roofs. Four days after the Aktion had been launched, the German troops withdrew. During the battle, 20 Germans were killed and 50 were wounded. However, also during the Aktion, the Germans succeeded in deporting between 5,000 to 6,500 Jews to Treblinka, slightly less than the intended number of 8,000. At the same time, approximately 1,000 Jews in the ghetto were killed during the battle or executed on the spot.

In spite of the Jewish Combat Organization’s heavy losses, its surviving members became highly motivated after the January’s battle. Not only was this the first time that Germans died in the ghetto because the Jews resisted, but the Jews were also convinced that their resistance had prevented the complete elimination of the ghetto. They could not have known that the Germans’ first plan was to deport 8,000 Jews. The complete evacuation of the ghetto took place about three months later. In the meantime, both the Germans and the Jewish resistance fighters could prepare for this Großaktion, as Jürgen Stroop called this mission [to deport the ghetto Jews to Treblinka] in his report.

Definitielijst

- Generalgouvernement

- That part of Polish territory occupied by the Germans in 1939. It was an autonomous part of Greater Germany. In August 1941 Eastern Galicia was added to the Generalgouvernement. It was governed solely by Germans under direction of Generalgouverneur Hans Frank. It was to become a full German province inhabited only by German colonists.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Preparation

Despite the fact that the result of January's battle was regarded as a victory over the Germans, the Jewish Combat Organization had suffered heavy losses. The ranks were supplemented and lessons were learnt from the events of January. Vigilance was further increased as the Germans could strike again at any moment. Military discipline was also accelerated and the difficult search for weapons continued. Although Jews were perfectly able to use the weapons against the Germans, large deliveries of arms were still lacking. Of the limited number of weapons made available by the Polish Home Army a large portion was in poor condition or unusable. A number of weapons were supplied by the Polish Workers' Party (PPR) and its military branch, the People's Guard (Gwardia Ludowa), who had fought alongside the Jewish fighters during the uprising. Eventually they managed to collect a few automatic rifles, a few dozen carbines, a few hundred pistols and a fairly large number of grenades and explosives. However, the ammunition supply was small. Due to the limited number of firearms, some resistance fighters armed themselves with knives, axes, hammers, pitchforks and pickaxes. Furthermore, weapons were taken from the Germans during the uprising.

On the eve of the uprising, ŻOB had formed 22 combat units, each of them representing a youth movement. In total, the organization consisted of 500 to 750 members, while the Jewish Military Union had another 200 to 250 members. Had there been more weapons, more fighters could have been trained.

At the same time, the non-combatants also had been prepared for battle. They were called upon by the ŻOB to "assemble themselves under the banner of struggle and resistance", according to an appeal of the Jewish Combat Organization of 3 March 1943. "Hide your wives and children and join us in the fight against Nazi scum. The Jewish Combat Organization is counting on your full moral and material support." As a result of the events of January, the popularity of the ŻOB among Jewish citizens had grown. Their morale had been boosted by the 'victory' over the Germans. Together with the resistance fighters they were helping to build underground bunkers and hiding places, where they could survive during the battle and from where the ghetto fighters could operate. An intricate network of underground cellars and tunnels had been created to connect the command posts with each other and with the streets outside the ghetto wall via the sewers. "How much precaution the Jews had worked with," wrote Jürgen Stroop in his report, "is proven by many established cases of furnishing the bunkers with housing for entire families, washing and bathing rooms, toilets, weapons and ammunition rooms and large food supplies for several months." There were separate bunkers for the poor and rich Jews. Due to the camouflage, finding individual bunkers was extremely difficult for the armed forces and in many cases it was only possible by Jewish treason.

What did the Jews want to achieve with the resistance they so diligently prepared? Did they really think they could save their lives by resisting the much more heavily armed and overpowering German occupiers? No, most Jews had no illusions and did not fight for their own survival. "When we began the uprising, none of us believed we would survive...", says Stefan Grayek, a Polish Jew who had taken part in the Warsaw ghetto uprising. "We had another goal: not to save our own lives, but to respond to murder and make them pay for it. It was the last chance to take revenge on the SS for all the murders they had committed in previous years. Nobody thought they'd survive. But at least I wanted to take revenge on those who had murdered my family, my friends and my people." Ahron Karmi, a Jewish fighter who wanted to avenge the blood of his father who had died in Treblinka, says the same. "We didn't think for a moment that we'd win," he says. "This was just to avoid being put on the train when they said we should go. If we were successful for one day, we'd try for another one."

Meanwhile, ŻOB also continued to liquidate ghetto inhabitants who collaborated with the Germans, including members of the Order Service and Jews spying for the Gestapo. The Germans were also risking their lives the moment they entered the ghetto. In the German reports of the time, the ghetto was even described as "a breeding ground of degeneration and rebellion.. This was one of the reasons for the Germans to proceed with the complete liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto very quickly. On 16 February 1943, Himmler had ordered the definitive evacuation of the ghetto. "For security reasons I decree," he wrote, "that the Warsaw ghetto should be destroyed after the concentration camp had been established.... The destruction of the ghetto and the establishment of a concentration camp are necessary, otherwise we will never be able to pacify Warsaw and the criminality stemming from the ghetto's existence will never be eradicated. A general plan of the ghetto's destruction must be presented to me. In any case, the existing space for the so far more than 500,000 living Untermenschen ... must disappear from the face of the earth ..."

The liquidation of the ghetto was executed under the supervision of Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger, the Höhere SS und Polizeiführer in the Generalgouvernement. The operation was led on site by SS-Oberführer Jürgen Stroop. He earned the reputation of a ruthless commander in the fight against partisans on the Eastern Front. The SS-Wirtschafts- und Verwaltungshauptamt under command of Oswald Pohl was responsible for the establishment of the concentration camp. When exactly this happened is unclear, but most sources mention 19 July 1943 - so only after the uprising - as the date on which Konzentrationslager Warsaw had been opened.

Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger, Höhere SS und Polizeiführer in the Generalgovernment. Source: U.S. National Archives

Jürgen Stroop (center), the man in charge of the liquidation of the ghetto. Source: U.S. National Archives

Before the German troops arrived in the ghetto to dismantle it, the Gestapo had been trying to disrupt the Jewish resistance movement from within. For example, they set up a so-called new resistance group that was to derail the Jewish Combat Organization’s plans by carrying out an early uprising which would lead to a massacre. However, the vigilance among the ghetto fighters was great, causing this German ruse to fail. Subsequently, a different approach was chosen. Jewish workers were told by the owners of the German ghetto workshops that they would be transferred to labour camps with very favorable working conditions. However, after everything that had taken place in the ghetto in recent years, the ghetto residents no longer accepted such deceitful promises.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Generalgouvernement

- That part of Polish territory occupied by the Germans in 1939. It was an autonomous part of Greater Germany. In August 1941 Eastern Galicia was added to the Generalgouvernement. It was governed solely by Germans under direction of Generalgouverneur Hans Frank. It was to become a full German province inhabited only by German colonists.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- liquidate

- Annihilate, terminate, destroy.

- moral

- The will of the troops/civilians to keep fighting.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Attack and defence plans

The final evacuation of the ghetto began on 19 April 1943 on the eve of the Jewish feast of Easter, Passover. Ghetto evacuations often took place on Jewish holidays as the Jews were less alert then. However, it is not known whether this date had been deliberately chosen. Adolf Hitler's birthday on 20 April possibly had also played a role, as the Germans may have wanted to present the evacuation of the ghetto as a gift to the Führer. Before the arrival of Jürgen Stroop, the first German attack plan was compiled by Ferdinand von Sammern-Frankenegg. His plan was to first surround the ghetto on the outside with machine gun nests. After this, he would send groups of men from a central point to different locations within the ghetto to pick up Jews. It is difficult to determine how many Jews were still in the ghetto at that time, since many went into hiding and were unregistered. Supposedly it was a maximum of 70,000 people.

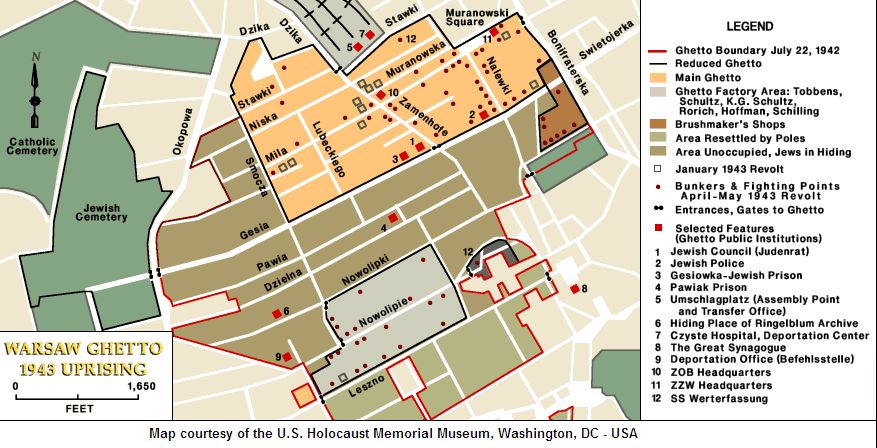

The tactic developed by ŻOB in the meantime consisted of two parts: first, they would attack the invading enemy from hiding places located behind windows and on attics and roofs. This way, it would be more difficult for the enemy to enter. After this tactic of attacking they would fall back. They would retreat to bunkers and shelters again and again, but at unexpected moments they would resume the attack. The ŻOB command led by Chief of Staff Mordechai Anielewicz was split into four battle groups of which the ŻZW was also part. The first battle group occupied the central ghetto, referred to by the Germans as the Restgetto, where the base of the ŻOB’s staff was also located. The second group was working in the area of the brush factories. The third group was responsible for the area around Muranowski Square. The so-called production ghetto was assigned to the fourth battle group. The core of the insurgent struggle was in the hands of the ŻOB, but other battle groups had also been formed, including groups of labourers from the workshops.

Altogether, ŻOB and ŻZW had at most 1,000 troops at their disposal, while Stroop had at least 2,000 troops from various ranks of the occupying forces, including the Waffen-SS, the Wehrmacht and the Ordnungspolizei. Other available troops included a battalion of Trawniki men, mainly Ukrainian volunteers from the Trawniki training camp who were also deployed as guards in the extermination camps of Aktion Reinhard. Below is an overview of the men deployed to suppress the uprising, compiled by Stroop. The numbers in the right-hand column are respectively the number of officers and men.

| Waffen-SS: | |

| SS-Panzer-Grenadier Battalion 3, Warschau | 4 / 440 |

| SS- Kavallerie Detachement, Warschau | 5 / 381 |

| Ordnungspolizei: | |

| SS-Polizei Regiment 22 I Battalion | 3 / 94 |

| SS-Polizei Regiment 22 III Battalion | 3 / 134 |

| Technische Nothilfe | 1 / 6 |

| Polish police | 4 / 363 |

| Polish fire brigade | 166 |

| Sicherheitspolizei: | 3 / 32 |

| Wehrmacht: | |

| Leichte Flakalarmbatterie III/8, Warschau | 2 / 22 |

| Pionierkommando, Rembertow | 2 / 42 |

| Reserve Pionier-Battalion 14, Gora-Kalwaria | 1 / 34 |

| Foreign security troops: | |

| Batallion Trawniki-men | 2 / 335 |

During the liquidation of the ghetto, Stroop also deployed 337 Trawniki men. Source: U.S. National Archives

Unlike the Jewish fighters, the German troops had an extensive arsenal of weapons at their disposal, including tanks, armoured cars, various artilleries, and flamethrowers. Having superior numbers of both men and weapons, Stroop expected the evacuation of the ghetto to last no more than three days. It soon became clear that he had strongly underestimated the Jewish resistance.

Definitielijst

- Batallion

- Part of a regiment composed of several companies. In theory a batallion consists of 500-1,000 men.

- brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- machine gun

- Machine gun, an automatic heavy quick firearm.

- Regiment

- Part of a division. A division divided into a number of regiments. In the army traditionally the name of the major organised unit of one type of weapon.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

First phase, the street battles

Around 2:00 in the early morning of 19 April 1943, the ghetto was completely surrounded by German troops and their collaborators. The ŻOB immediately put the ghetto in the highest state of preparedness. The fighters could not leave their positions, and entrances and courtyards were barricaded. A state of alert was also declared for the civilian population of the ghetto. Armed ŻOB fighters scoured the ghetto and advised everyone to immediately go into hiding to the underground shelters. At the same time, they covered the walls with mottos such as "Honorable Death!" and the appeal: "To arms! Women and children to the air raid shelters!" They also hung flags in highly visible places within the ghetto.

When Sammern's troops entered the ghetto, it gave a deserted impression. The Germans’ very first goal was to evacuate the central ghetto. Sammern still hoped that the Jews would voluntarily report to the Umslagplatz. Together with the troops, he also sent a car with a loudspeaker into the ghetto. Through the loudspeaker the Jews were summoned to voluntarily leave their hiding places and to report for transport. Seemingly out of nowhere, the German troops were stopped by attacks on Nalewki Street and at the intersection of Zamenhof and Miła Streets. On Nalewki Street, at the intersection with Gęsia Street, a German column came under fire from balconies and roofs and from behind windows. The German troops were taken by surprise and fled, but returned after the officers restored order within their ranks. At the same time, Sammern sent reinforcements to the troops on Nalewki Street. The battle lasted about two hours in total, but in the end the Germans had to fall back losing, while no Jewish fighters died.

Similarly, the Jewish fighters’ first attack on the German troops at the intersection of Zamenhof Street and Miła Street was also successful. The main base of the rebels was located on Miła Street. The Germans considered this part of the ghetto as the root of the resistance and their goal was to take over Miła Street on the very first day. They intruded far along Miła Street with a tank and two armoured cars, but were then suddenly attacked from different sides with grenades, Molotov cocktails and gunfire. The tank caught fire and was shut down, and presumably the same thing happened shortly afterwards with the armoured car. Stroop described in his report that "The tank and two armoured cars used in the battle were bombarded with Molotov cocktails .... The tank caught fire twice. This attack resulted in the withdrawal of the units used in the battle. Losses during the first attack: 12 men (6 SS men and 6 Trawniki men)." The rebels, on the contrary, had lost only one fighter during the battle that had lasted about half an hour.

At 8:00 in the morning, after Sammern had been defeated twice, Stroop took over the command. Stroop decided to no longer follow Sammern's evacuation plan. Instead of sending several of his troops scattered into the ghetto to carry out round-ups, he had his forces take turns attacking the main positions of the Jews. It was also his intention to put the ghetto and its inhabitants into a pincer grip and to push the rebels gradually into a smaller and narrower area in order to eliminate them with concentrated forces. The main objective was to take control of the area between Zamenhof and Nalewki Streets, the main thoroughfare in the central ghetto and the primary center of resistance. Stroop first relaunched the attack on the resistance fighters on Zamenhof Street. Some of his men were killed, but in the end he managed to force the rebels to retreat. At noon he undertook a second attack on the Nalewki Street positions. Here, too, the rebels were forced to retreat following a battle that lasted a total of six hours. The Germans took their revenge by bombarding the hospital on the Gęsia Street with heavy artillery. German troops then invaded the bombed building and massacred the patients.

After the resistance center on Nalewki Street had been cut out for the time being, a third battle broke out in the centrally located Muranowski Square. The Jewish armed forces fought here to the bitter end, and despite his extra forces, Stroop did not succeed in breaking their resistance. The action was interrupted by Stroop at 8:00 in the evening. After the sentries outside the ghetto had been reinforced, all the German troops retreated from the ghetto. During the first day they had supposedly apprehended only 380 Jews. Hans Frank, the head of the Generalgouvernement, informed Berlin about the dire situation. "Since yesterday we are dealing in Warsaw with a well-organized uprising in the ghetto, against which we have to deploy heavy artillery," he wrote. "The number of Germans being murdered is increasing at a frightening rate."

Jewish warriors being questioned by the SS. Stroop is third from the left. Source: U.S. National Archives

The next day, 20 April, German troops returned to the ghetto and gave the Jewish fighters an ultimatum. They threatened that if the Jewish fighters would not surrender, the entire ghetto would be razed to the ground. The Jews ignored this ultimatum and relaunched the attack. The approach of the Germans then became tougher. They surrounded the ghetto not only with machine guns, but also with light artillery. Presumably, a few hundred Jews were executed on the spot that day as revenge for the death of SS-Untersturmführer Otto Dehmke, the first officer to have died during the action.

From 20 to 22 April, there were other fights in Muranowski Square, but the main battle took place on the grounds of the brush factory. The attack in this area was personally led by Stroop and began on 20 April at 3:00 in the afternoon. During the first attack, the Germans suffered heavy losses and retreated, leaving their dead and wounded men on the streets. After a short time they relaunched the attack, but again without results. The brush factory’s director was sent by the Germans as a negotiator to call a truce, while at the same time the Germans were setting fire to the buildings. The Jews rejected the enemy's offer, and the battle continued. The Germans realized that they could not conquer this part of the ghetto by assaulting the Jewish positions. This is why the decided to bomb it instead. That day, however, they were no longer able to break down the resistance inside the grounds of the brush factory, but the heavy fires had another result: the Jewish fighters fell back in the night of 21/22 April after having evacuated the civilian population. Heavy fighting also took place on 20 April on Miła Street and in the area around the workshops.

Despite their losses, the Jewish fighters were joyful about the results they had achieved so far. When the battle had been already going on for five days, Mordechai Anielewicz wrote in a letter on 23 April 1943: "The dream of my life has come true. The Jewish self-defense in the ghetto has become a fact. The Jewish revenge has taken real forms. I witnessed the unheard-of strength and courage with which the Jewish fighters fought." "It was the first time we saw Germans running away," says Ahron Karmi, who fought along during the uprising. "We were used to being the ones who ran away from the Germans. They have never expected the Jews to fight like this. The blood was flowing and I couldn't take my eyes off it."

Definitielijst

- Generalgouvernement

- That part of Polish territory occupied by the Germans in 1939. It was an autonomous part of Greater Germany. In August 1941 Eastern Galicia was added to the Generalgouvernement. It was governed solely by Germans under direction of Generalgouverneur Hans Frank. It was to become a full German province inhabited only by German colonists.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Second phase: the battle for the bunkers

The enormous effort undertaken so far to defeat the ghetto uprising was met with great displeasure in Berlin. On 23 April 1943, Heinrich Himmler therefore issued the order that the operation should be continued "with greater harshness and relentless severity." Jürgen Stroop then decided - as can be read in his report of May 16 - "to completely destroy the Jewish residential district by burning down all residential blocks, including those near the weapons factories. One company building after another had to be emptied and then destroyed by fire." By burning down the ghetto, blowing up cellars and bunkers and destroying the streets, he wanted to force the Jews out of their hiding places and to seize the insurgents' positions within the housing blocks. There were Jews who reported for deportation out of despair or hunger, but most of the Jews remained in hiding, while the Jewish fighters continued their battle from the bunkers. When their hiding places were no longer habitable due to fire, the fighters would flee to other positions. ŻOB had to evacuate the civilian population to safer shelters several times.

The battle was continued by the ŻOB in a different way than during the first phase. Previously, the fighting had mainly taken place above ground, but now the resistance came mainly from the bunkers. The tactic was to fire at the enemy when he attacked, while a second group attacked from behind through secret exits of the bunker. The ghetto fighters came out of their underground shelters mainly at night, to attack German troops, to seize weapons and to carry out reconnaissance. In order to not attract attention, the Jewish fighters were usually dressed in German uniforms and wore rags around their feet. Normally, there would be several heavy fights taking place at night. On 25 April, the insurgents suffered the heaviest loss so far. A group of scouts trying to reach the 'Aryan' residential area through the sewers had stumbled upon an enemy patrol, and the resistance fighters were killed in an unequal battle. Nevertheless, the Jewish fighters continued their nighttime raids on German patrols and kept trying to get in touch with the Polish resistance outside the ghetto.

On 26 April the Polish resistance on the 'Aryan' side had received probably the last report from the ŻOB's high command. "For eight days now we have been engaged in a deadly battle," they wrote. "The Germans suffered numerous losses, the first two days they were forced to retreat. Later on, they had reinforcements brought in, including tanks, armoured cars, artillery and even planes that came into action for the planned siege. Our losses, i.e. victims of fusillades and fires in which men, women and children were killed, are very significant. Our last days are approaching. But we will continue to fight and to resist as long as we hold weapons in our hands."

Ghetto dwellers are taken away after having been dragged from their subterranean hide outs. Source: U.S. National Archives

The battle carried on into several locations, including the workshops grounds where the first battle had broken out on 20 April. Several shelters there were taken over on 27 April by Stroop's men. This was made possible by flooding the shelters. Heavy fighting took place again in the area around Muranowski Square, in which the Jewish fighters were supported by the Polish resistance. Some fights took place outside the ghetto, which led to arrests of many Polish citizens suspected of being involved in the resistance in this area.

Of the 26 streets in the ghetto, 20 were on fire on 27 April. "A dense, caustic smoke hung in the streets of the ghetto," we read in the ŻOB’s report. "Thousands of women and children were burned alive in their homes. There were horrible screams and cries for help coming from the burning houses. Through the windows you could see people seized by flames, emerging in front of the houses like living torches." It often happened that Jews jumped to their death from burning houses. Sometimes they tried to break their fall by throwing mattresses on the floor first. "With broken bones, they tried to crawl through the streets into blocks of houses that were not yet or only partially on fire," wrote Jürgen Stroop. Many Jews preferred suicide to imprisonment by the Germans which would certainly lead to their death. Despite these miserable conditions, the resistance continued, and after twelve days of fighting there was still some leadership and coordination, although the connections between the bunkers had worsened.

There were several important battles taking place in the first week of May. The tragic low point for the Jewish fighters was the fall on 8 May of the ŻOB’s staff bunker, in which the resistance leaders died. However, they did not go down without a fight. On 1 May, the Jewish fighters decided to attack the German troops from their base on the Nalewki Street during the daytime. After some of their men were killed, the Germans fled. After a while, however, they returned and began attacking the Jewish fighters from all sides. Without any losses, the Jewish fighters retreated to their headquarters at 18 Miła Street.

From 1 to 3 May, there was also a battle over a bunker on Franciscan Street where fighting troops that previously had scattered elsewhere now gathered. Their bitter fight came to an end when the Germans used gas to drive the Jews out of their shelter. Whether this was actually gas is doubtful, since Stroop reported that he frequently used smoke candles - a kind of smoke bomb - which Jews thought to be gas. The Germans eventually failed to deport Jews from Franciscan Street. About half of the Jews were killed and the rest retreated, namely to the bunker at 18 Miła Street. Meanwhile, on 2 May there was also a heavy fight on Stawki Street. Several Jews were able to find refuge in the Mila Street shelter after the battle.

From 4 to 7 May 1943, the last battles were fought on the workshop grounds. Lack of ammunition, hunger, and increasing losses weakened the resistance, although the Jews fought relentlessly until the final hours. Several bunkers were eventually destroyed by Stroop's troops, breaking down the resistance. Stroop mentioned 49 bunkers in his daily report. In addition to being defeated at the workshops, on 7 May the Jewish fighters also lost a group of scouts trying to get outside the ghetto wall. Other Jewish fighters had successfully escaped from the ghetto and tried to join partisan groups in the woods.

The following report of the Polish police, the so-called Blaue Polizei (which was part of the Kriminalpolizei) gives a description of what the ghetto must have looked like from 5 to 7 May: "The ghetto looks like a mass grave. Patrols, armed with fast-firing rifles and machine guns on various street corners guard the smouldering ruins of burnt down houses. Watchful and anxious, the SS look out at the shadowy debris to make sure no shot is fired from its side or from behind. The Jews emerge like ghosts from the smouldering ruins where they had built their bunkers; they take down the weaker of the German patrols to the very last man or they flee like ghosts across the smoking ruins of charred houses towards the Aryan quarter."

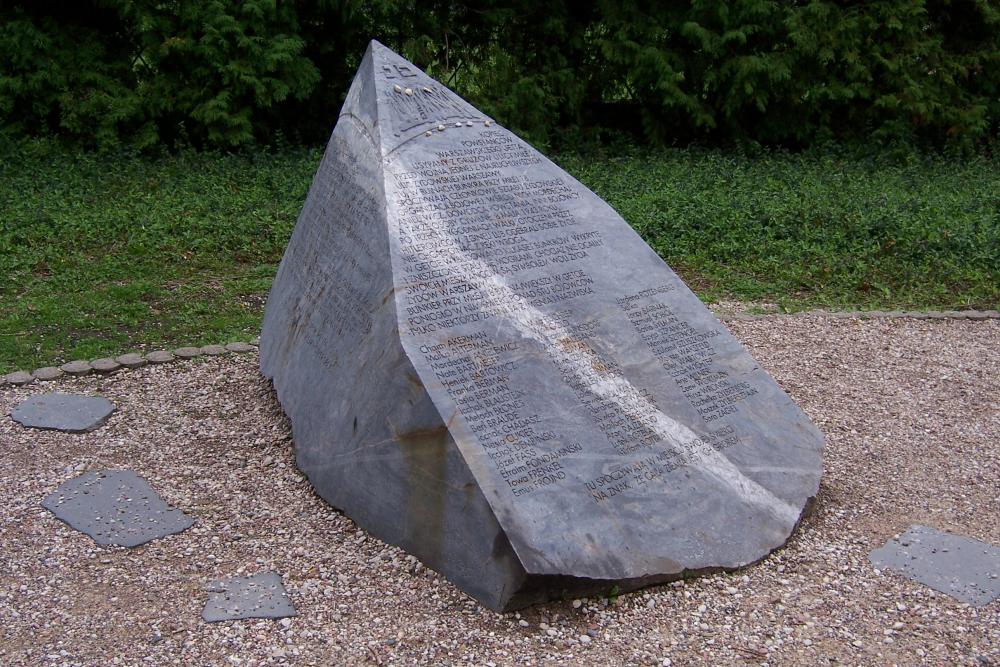

The battlefield became gradually smaller during the first ten days in May. The main battles were fought on Miła, Dzika, Wołyńska and Szczęśliwa Streets and in some adjacent streets. The most important of the ŻOB’s bases in this part of the ghetto were located at 18 Miła Street, 35 Nalewki Street and 22 Franciscan Street. The most important leaders of the rebellion gathered in their headquarters in the bunker at 18 Miła Street. Their shelter was tracked down by the Germans on 8 May. The shelter was surrounded on all sides, and the German troops launched their attack. They threw gas bombs or smoke candles through the entrances of the bunker. After fierce resistance, the Jewish fighters ran the risk of suffocating and decided to take their own lives. Others were killed during the fight. One of the Jews who died in the bunker at 18 Miła Straat was Mordechai Anielewicz, the leader of the revolt. This however did not end the uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Definitielijst

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Third phase, the battle in the ruins

After the street fighting in the first phase and the defense fighting in the bunkers during the second phase, the ŻOB's headquarters fell, and the third phase of the uprising began, taking place in the rubble and ruins of the destroyed ghetto. There was no central leadership, and the remaining battle groups no longer had any fixed operating bases. They moved constantly from one place to another and had only sporadic contact with the Polish resistance.

On the night of 13/14 May, the Soviet air force bombed German positions and military objects in Warsaw. Bombs had also been dropped near the ghetto and on the Pawiak prison inside the ghetto. The Jewish fighters took advantage of the panic that broke out among the Nazis and attacked German patrols several times. Using chaos as cover, several attempts were made to flee the ghetto, but only a small number of Jews managed to reach the Aryan side. Even after the bombardment, Jewish fighters still tried to break through the cordon that surrounded the ghetto and to flee. It is difficult to determine how many Jews fled during the uprising. It is estimated that about 20,000 Jews managed to go into hiding in residential areas outside the ghetto or to disappear into the forests in eastern Poland. Many of them were later arrested by the Nazis, died during partisan fights, or were killed by anti-Semitic Polish partisan groups.

On 15 May 1943, the last buildings within the ghetto were destroyed. A day later, the Great Synagogue of Warsaw on Tłomackie Street was blown up. This was the symbolic end of Stroop's operation. He informed Himmler and Krüger via telex that the former Jewish ghetto no longer existed. "At present, all the businesses in the former Jewish residential district are gone," he wrote. Everything of value that was there, and all the resources and machines were removed and relocated. All existing buildings and the like were destroyed. According to Stroop, 56,065 Jews were killed during the fight or were deported. Many victims of the fires and explosions were not taken into account; so the total number of victims who had died in the ghetto or had been deported was actually a lot higher. The majority of the victims were non-combatants. Stroop reported daily the number of resisters killed, and his numbers add up to a total of 5,565.

In his final report, Stroop mentioned the names of 15 German soldiers and 1 Polish policeman who died in the battle for the ghetto. He also mentions the names of 60 Waffen SS men, 11 Trawniki men, 12 Sicherheitspolizei officers, 5 men of the Polish police and 2 Wehrmacht pioneers who were wounded during the operation. However, the numbers were actually higher, as Stroop himself later admitted. The Jewish National Committee estimated that there were about 300 dead and about 1,000 wounded among the Germans and their collaborators. Two Polish resistance newspapers estimated that the German losses amounted to 400 dead and more than 1,000 injured.

As a memento of the Großaktion, Stroop had his reports compiled into a fine book, bound in black textured leather and illustrated with 54 photographs, bearing the title Es gibt keinen jüdischen Wohnbezirk mehr in Warsaw. Three copies were printed: one for Stroop himself, one for Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger and one for Himmler. One photograph from this book pictures a Jewish boy under military guard being taken away with his hands in the air, together with other civilians. "Forcibly pulled out from bunkers" was the caption in Stroop's book. The German historian, Guido Knopp, wrote, "No other photograph so poignantly symbolizes how defenseless the Jews were in the capital of Poland to the bloodhounds of the SS."

To commemorate the victory, General Governor Hans Frank visited the ruins of the ghetto on 18 June. Still, the resistance in the ghetto did not completely stop after Stroop's operation had been officially terminated on 16 May. "Despite the fact that many newspapers are already heralding the end of the battle in the ghetto," we see in Głos Warszawy (The Voice of Warsaw) of 8 June 1943, "a handful of ghetto defenders are still present. Over the past few days, they have been carrying out a lot of raids outside the ghetto wall, killing some gendarmes and forcing the occupants to call for reinforcements." In order to deal with the last remaining Jews, Stroop had kept back the Polizei-Bataillon III/23. At night small commandos of Ukrainians and Latvians were sent into the ghetto to track down and eliminate Jews. The Jews were also bullied by looters, who were looking through the rubble for any valuables.

The fights in the ghetto continued until the first days of July. After that, the resistance fizzled out, partly because the ammunition supply of the fighters had run out. The police battalion had also continued to demolish the ruins, so that there were hardly any hiding places left for the Jews. Nevertheless, the Jews would still stay in ghetto ruins. Many of them died in the winter of 1944.

Definitielijst

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Synagogue

- Jewish house of prayer.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Aftermath

After the Warsaw ghetto had been entirely liquidated, Aktion Reinhard also came to a halt. The majority of the Generalgouvernement's Jews had been murdered, and Heinrich Himmler ordered the dismantling of the extermination camps in Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka. From March 1942 to November 1943, a total of 1.7 million Jews were murdered in these extermination camps. A further 42,000 to 43,000 Jews from the Generalgouvernement were murdered during Aktion Erntefest (Operation Harvest Festival) in the autumn of 1943. These numbers include several thousand Jews from the Warsaw ghetto living in a few residual labor camps. A general Polish uprising broke out in Warsaw in August 1944. Several hundred Jews also fought along with the Polish Home Army. The uprising failed and Warsaw was destroyed to the ground. On 17 January 1945, Warsaw was finally liberated by the Soviet army. Another 300 Jews were found hiding among the city ruins, including the pianist Władysław Szpilman who stayed alive thanks to the help of Wilm Hosenfeld, a Wehrmacht officer.

After the war, many people wondered how it was possible for the Nazis to slaughter 6 million Jews. It was assumed that the Jews had resisted little or not at all and had allowed themselves to be led to the slaughterhouse like docile lambs. This is a false assumption, because the Warsaw ghetto uprising was not the only Jewish resistance action during World War II. Rebellions broke out in several other ghettos, usually when the final liquidation had been announced. One such example is Białystok, where an uprising broke out on 15 August 1943 and lasted five days. Many hundreds of Jews died during the fights or were deported, but several dozen Jews managed to escape and flee to the woods around Białystok. Uprisings were organized even in the extermination camps, such as the Treblinka uprising on 2 August 1943 and the Sobibor uprising on 14 October 1943. After the evacuation of the ghettos and the liquidation of the extermination camps, the Jewish escapees fought from the swamps and forests of Eastern Europe, where they had joined partisan groups. The Jewish resistance could not have prevented the genocide, but those who claim that the Jews allowed themselves to be led en masse to the slaughterhouse like docile lambs ignore many actions of brave resistance against a much stronger opponent.

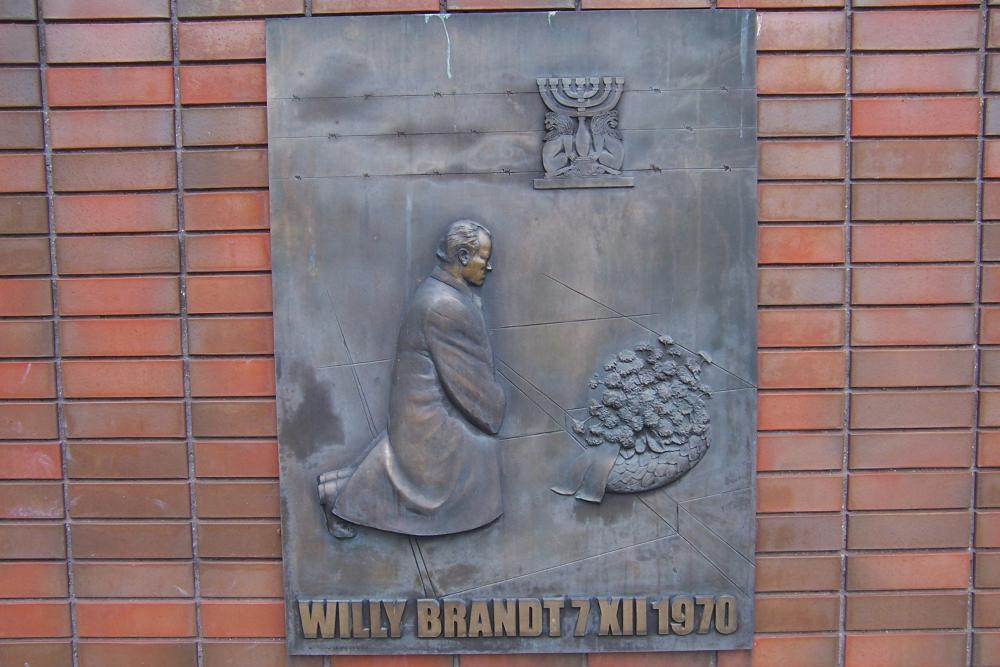

After the war, the Jewish survivors of the ghetto uprising and other Holocaust survivors founded in Israel a kibbutz Lohamei HaGetaot, known in English as The Ghetto Fighter's House. The kibbutz houses a museum and archives related to the Holocaust. A monument was erected in Warsaw to commemorate the Jewish fighters of the uprising. In 2005, a Jewish history museum was built in the heart of the former Warsaw ghetto.

Definitielijst

- Aktion Erntefest

- “Operation Harvest Festival”. Code name for the German operation in the autumn of 1943 to exterminate all remaining Jews in the district of Lublin. It was a reaction to Jewish acts of resistance in the Generalgouvernement such as the uprisings in Sobibor and Treblinka. The operation started on 3 November 1943. Within a few days approximately 42,000 Jews were murdered.

- Generalgouvernement

- That part of Polish territory occupied by the Germans in 1939. It was an autonomous part of Greater Germany. In August 1941 Eastern Galicia was added to the Generalgouvernement. It was governed solely by Germans under direction of Generalgouverneur Hans Frank. It was to become a full German province inhabited only by German colonists.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Information

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Translated by:

- Ewa Kotz

- Published on:

- 07-02-2021

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- ARAD, Y., Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, Indiana University Press, Bloomington (USA), 1999.

- BREITMAN, R., Heinrich Himmler, Verbum, Laren, 2005.

- HILBERG, R., Daders, slachtoffers, omstanders, Becht, Haarlem, 2004.

- KERSHAW, I., Hitler - Vergelding 1936-1945, Het Spectrum, Utrecht, 2003.

- KNOPP, G., Hitlers Holocaust, Byblos, Amsterdam, 2001.

- KNOPP, G., Hitlers moordenaars, Het Spectrum, Utrecht, 2004.

- MARK, B., Strijd en ondergang van het getto in Warschau, Westfriesland, Hoorn, 1979.

- POHL, D., Holocaust, Verbum, Laren, 2005.

- READ, A., Discipelen van de duivel, Balans, Amsterdam, 2004.

- REES, L., Auschwitz, Anthos, Amsterdam, 2005.

- SNYDER, L., Encyclopedia of the Third Reich, Wordsworth, Hertfordshire (UK), 1998.

- SPECTOR, S. & ROZETT, R., Encyclopedie van de Holocaust, Kok, Kampen, 2004.

- With thanks to Anne Palmer.