Introduction

Heinrich Hoffmann, the personal photographer of the Führer was a man who did not come to the foreground often but was a prominent figure within the Nazi regime nonetheless. Apart from the fact that he was an important coq in the propaganda machinery of the Third Reich, he was seen regularly in the vicinity of prominent Nazis, a confidant of Hitler and he even competed with Goebbels for the most intimate bond with the Führer. After his arrest in May 1945, the same man who shot pictures for dozens of years in order to glorify Nazism would now be obliged, using the same pictures, to help the courts try the Nazis remaining after the war he had seen through his lenses.

Definitielijst

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Nazism

- Abbreviation of national socialism.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

Images

Step up to a shining career

Heinrich Hoffmann was born October 12, 1885, in the provincial town of Fürth in the German federal state of Bavaria, the son of photographer Robert Hoffmann and his wife Maria. Photography was second nature to him. At the age of 11, he already could be found in the photo studio of his father where he came to appreciate the art of portrait photography. It turned out he was gifted and his father enabled him to further develop his talents. Hoffmann decided to widen his horizon and at the age of 16 he went to several German cities like Darmstadt, Heidelberg, Frankfurt, Bad Homburg and Zürich, Switzerland to learn the trade from other photographers. Among these were Anita Augspurg and Sophia Goudstikker, owners of the famous Studio Elvira in Munich, the first company in Germany established by women. "Ausgezeichnete Fotografinnen" (perfect photographers) Hoffmann called them. Hoffmann had made an eternal name for himself in Germany with his choice of working as an apprentice with other photographers but international success soon followed.

In 1907, Hoffmann decided to pursue his fortune abroad. He crossed the Channel in order to enter apprenticeship with the most famous art photographer in Great Britain, Emil Otto Hoppé. He had his first success during the Franco-German exhibition of 1908 in London. Hoppé had sent him there to take pictures of the colonial section. He had scarcely arrived when a loud bang sounded and people started running around in panic. A balloon, meant to do sightseeing tours with visitors, had exploded. Hoffmann took a picture of the still burning wreckage of the balloon and that picture appeared on the front page of the Daily Mirror the next day. As Hoppé had sent Hoffmann to take pictures, Hoppé and not Hoffmann got all the credit. His place of learning in the Hoppé studio had now been secured though and he was sent out more often to take pictures of special events. Hoffman also shot the pictures for a picture book he published together with Hoppé entitled "Männer des 20. Jahrhunderts" (men of the 20th century). This gave him the opportunity to photograph celebrities including members of the British Royal Family. In addition he took pictures for Scotland Yard and of one of the first flights of the pioneers of aviation Wilbur and Orville Wright.

After having been an apprentice with Hoppé and others long enough, Hoffmann opened a studio of his own at 298 Uxbridge Road. The studio provided him with sufficient means he needed to make his dream come true: his own photo studio in Germany, a dream he had fostered since his youth. He felt his chances for success were far better there than in any other country. His dream became a reality in 1909 at the age of 24. A property was rented and the first Hoffmann studio opened its doors on 33 Schellingstraße in Munich. in 1911 he married Therese "Nelly" Baumann and had two children with her: Heinrich and Henriette. The latter would marry Reichsjugendführer Baldur von Schirach on March 31, 1932.

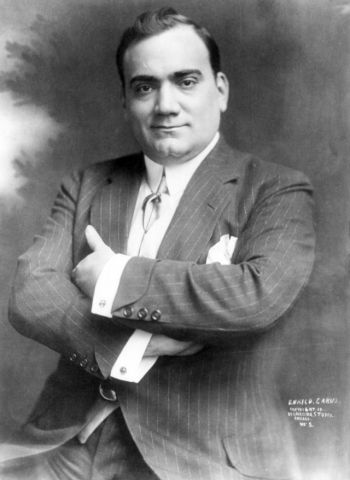

In 1910, Hans Fürstenheim, editor-in-chief of the Münchener Illustrierte Zeitung crossed his path. Famous Italian tenor Enrico Caruso was in town and he stayed in Hotel Continental. Caruso’s agency had imposed a ban on Fürstenheim, meaning people not employed by the agency were prohibited to take pictures of the singer. Fürstenheim ordered Hoffmann to take pictures of Caruso anyway. The picture would appear on the front page and Hoffmann would receive a sizable amount of money. Dozens of photographers had assembled at the entrance to the hotel as Caruso had to come out some time or other. This however was too easy for Hoffmann, he wanted that one and only picture no one else had. He managed to talk his way in by claiming he had been asked by Caruso himself to take pictures of him. Without any problem, he reached Caruso who even posed for him as he assumed it actually was for a picture ordered by his agency. With this bold action, Hoffmann had found himself a new customer for his work. In 1913, Hofmann decided to focus on press photography and portraits. In addition he distributed postcards that were delivered to enterprises in Germany as well as in foreign countries.

During this period Hoffman was admired by many people in Munich but in the field of general photography he did not belong the top. He mainly made portraits while the better known people engaged in photography were either art photographers or journalists. While these photographers had studios in crowded quarters or on important streets, Hoffmann’s studio was located in a court yard. However, in the field of portrait photography he did belong to the top. This was to emerge strongly during the Second World War when Hoffmann accounted for many portraits of highly decorated Germans including a large number of recipients of the Ritterkreuz (Knight’s Cross) on his postcards.

Images

First World War

In 1914, the First World War erupted. When news reached Munich about the Austro-Hungarian Empire having declared war on Serbia, a crowd took to the streets. The interior of Café Fahrig near the Karlstor in the center of Munich was completely destroyed because the musician refused to play "Die Wacht am Rhein," a song adored by the nationalists. A large crowd which had assembled on the Odeonplatz on August 2, 1914 sang this song at the top of their voices though. Hoffmann took a picture of this. It would appear as late as 1929 that Adolf Hitler was also in this crowd. When Hoffmann found out Hitler had been in the square that day in 1914, he looked over his old pictures once again and on one of them he did indeed find Hitler’s face. Nowadays doubt has risen about this story as another print of the picture has emerged in which Hitler’s characteristic tuft of hair looks clearly different. This meant the picture had probably been tampered with for purposes of propaganda. If that also means Hitler was completely invisible in the original picture is not clear.

On August 17, 1914, Hoffmann received news he had been admitted as a war correspondent by military supreme command. He was ordered to report to the local military commander in Metz, a Germany city at the time, where he was granted the necessary credentials to commence work as photographer in the field. In 1914, only 7 photographers were admitted to the war zone of whom Hoffmann was the only one from Bavaria. Hoffmann however found the fighting at the front too risky and he shot his pictures far behind the front lines. In his pictures, he showed soldiers playing cards, eating or staring into the distance, their rifles at their feet. These pictures were mainly published in newspaper and magazines. Seven months after the start of the war, the photographers themselves were drafted into the ranks. Hoffmann was posted to Fliegerabteilung 298. He sat in the back in a two-man airplane shooting aerial pictures of battlefields and enemy positions. On return he had to develop these pictures himself in a laboratory to provide the army with information on enemy positions.

In the spring of 1918, Hoffmann was admitted to hospital for stomach and heart problems and in May he was transferred to Schließheim near Munich. He has never been a war hero, contrary to what he was called later on in Nazi publications. In November 1918, the month in which World War One ended and revolts erupted all over Germany, he was discharged from military service. It is suggested that Hoffmann started thinking about the ideological function of photography because of these revolts. Regarding the rapid developments in politics in Germany and especially in Munich, this is understandable. Within a few months, King Ludwig III of Bavaria was dethroned and Freistaat Bayern was declared. A government was formed consisting of Communists and National democrats but following elections this coalition was disbanded again. Socialist leader Kurt Eisner was murdered; a short-lived socialist government was formed and the Münchener Radenrepublik was declared, headed by Communists and anarchists. However, early May 1919 this Radenrepublik also met its end. The best known pictures, shot in Munich in the period of uprising, are those of Hoffmann. It does not mean in any way, Hoffmann had Communist or socialist feelings. He was after all a professional photographer and the pictures he shot were too widely varied to be considered propaganda for whatever party. They show the so-called Communist Red Army in Munich but the troops of the counter-revolutionaries and the Freikorpse of May 1919 as well.

Definitielijst

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

Images

Rise of Nazism

The revolution ended in 1919 and in the monetary field, the inflation hit at full strength. As a result of the Treaty of Versailles, a hyperinflation arose in Germany causing the value of the German Reichsmark to drop to almost nothing. Hoffmann was forced to sell his studio for 7,000 Reichsmark. He was able to buy a second hand camera for half that amount and 10 eggs for the other half. He joined a movie company further down the road, 50 Schellingstraße. Hoffmann became the Standfotograf (still photographer, someone shooting pictures of particular scenes for purposes of advertizing) but he saw more opportunities for himself if he could start on his own again. Together with Martin Kopp and Atto Marsani, he founded the firm of Hokomar, aimed at movie production. Hoffmann wrote the scripts and filmed, Kopp saw to the technical side and Marsani was the director.

The three of them produced only one movie about a hair dresser who had invented an agent for growing hair and so became the hero of the movie. Twenty years on, Hoffmann would tell Hitler he had also produced a movie and Hitler very much liked to see it. An old copy was dug out of the cupboard and projected on the wall of the Reichs chancellery. Naturally, propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels was invited too to see the movie, which in hindsight was not the best thing to do because when the movie had hardly started, Hoffmann realized that hair dresser Pinselweich, the star player of the silent movie had a club foot. Goebbels could not appreciate this at all: "Das ist geschmackslos von Ihnen, Hoffmann" (That is quite tasteless of you, Hoffmann) he had cried out. Goebbels continuously suffered from an inferiority complex because of his club foot and in order to remind people as little as possible of his own handicap, he had all movies removed from the cinemas in which persons showed bodily disorders.

With membership number 59, Hoffmann was one of the very early members of the N.S.D.A.P., Adolf Hitler’s party. He joined the party on April 6, 1920 and again on March 24, 1925 after the ban on the party was lifted, imposed after the Bierkellerputsch of November 9, 1923 which was carried out by the Nazis. Hoffmann began taking an interest in Hitler on October 30, 1932 when he was offered a deal from New York. He was to shoot a picture of Hitler and would receive US $ 100 for it. In order to get close to Hitler, he decided to visit a close friend who was a good friend of Hitler as well: Dietrich Eckart. He was a playwright and Hitler’s mentor. Hoffmann and Eckart had met once across from Hoffmann’s studio on Schellingerstraße and a friendship had arisen from this meeting. When Hoffmann asked Eckart about the possibility to photograph Hitler, he did not get the answer he wanted to hear. It would cost him $ 30,000 to be permitted to take a picture of Hitler. if ever someone would pay that much money, Hitler could make good use of it to tighten the security of the rooms in which he delivered his speeches. The real reason to make photographing Hitler as difficult as possible was a political one. This way, the German citizens would be hearing all about Hitler but never see him. They would come to the party meetings out of curiosity to see who he was and leave the meeting as registered members.

In the economic sphere, the situation in Germany was still bad as a result of the Treaty of Versailles and even Hoffmann saw the N.S.D.A.P. not only as a customer but also as the solution of the economic problems of the country. After the fresh start of the party in 1925, Hoffmann would become more involved with the party. From 1929 onwards for instance, he was a member of the municipal council of Munich although he did not play an important role in it.

Owing to the N.S.D.A.P. Hoffmann’s work was mainly aimed at glorifying Hitler and portraying him as advantageously as possible. Hoffmann still did his utmost to shoot many important pictures. On February 26, 1924 another opportunity presented itself: the start of the trial against Adolf Hitler. Four months prior to the trial, Hitler had carried out the Bierkellerputsch mentioned earlier, together with some comrades of the time, including SA leader Ernst Röhm. The trial against Hitler drew large crowds but shooting pictures inside the court room was forbidden. Hoffmann would not have been Hoffmann though if he did not do anything in his power to shoot such pictures anyway. To that end. he stuck a button like mini camera on his jacket. The picture Hoffmann took has never been found anywhere, giving rise to the assumption it has always remained in Hoffmann’s private collection.

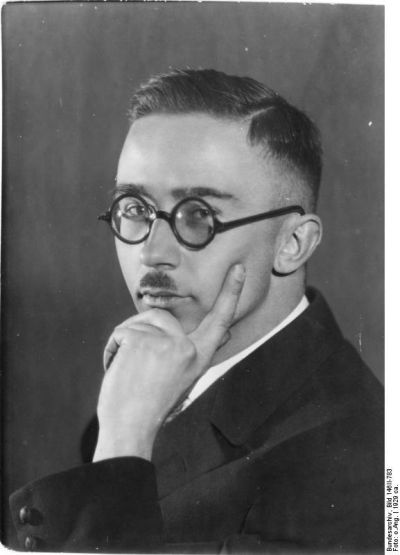

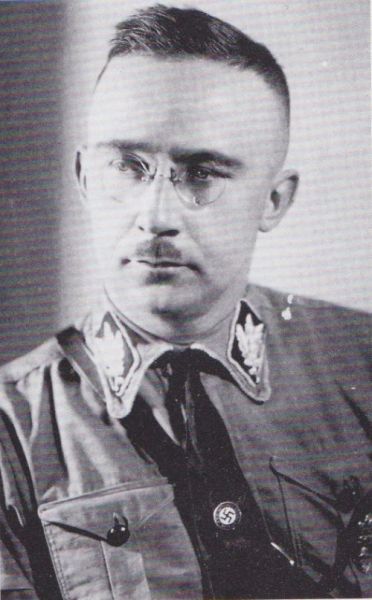

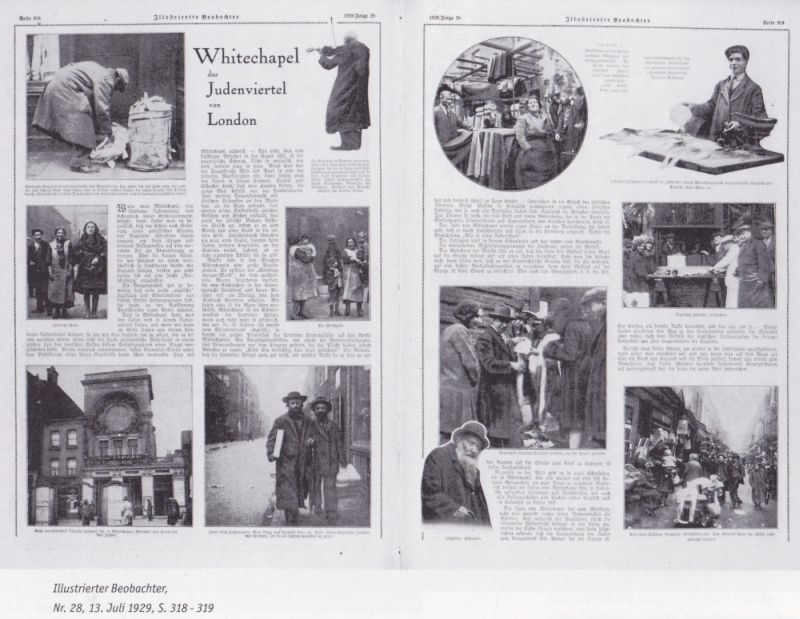

In order to prevent the party from dying a silent death, Hoffmann did everything to draw the citizen’s attention to the party. Consequently, he shot many pictures with a political background and as a result, many of his clients were followers of the N.S.D.A.P. He made portraits of prominent party members such as Hermann Göring, Joseph Goebbels, Heinrich Himmler, Ernst Röhm, Wilhelm Brückner (Hitler’s adjutant) and Gregor Strasser. In order to spread the extreme-rightist ideology further, the party took over the Illustrierte Beobachter, a paper mainly consisting of pictures. This way, the paper would remain a major buyer of Hoffman’s pictures throughout its entire existence up until 1945. He even traveled to the Jewish quarter White-Chapel in London, shooting pictures of a Jew sifting through garbage, Jewish workers, orthodox Jews and images of messy streets. These were of course carefully chosen since street views like those did not exist in the entire quarter. The report was only meant to strengthen the humiliating ideology of the Nazis. Around 1924, Hoffmann was appointed exclusive photographer and companion to Hitler during his travels. As his "escort" Hoffmann would follow Hitler anywhere he went, also on his election tours, the so-called Deutschlandflüge (flights across Germany).

Definitielijst

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- inflation

- An economic process of sustained increase in general price levels and devaluation of money.(loss of purchasing power)

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- revolution

- Usually sudden and violent reversal of existing (political) the political set-up and situations.

Images

Campaign photographer and Hitler’s confidant

As far as known, Hitler has had relationships with three much younger women: Maria "Mimi" Reiter, Geli Raubal and Eva Braun. His relationship with Mimi began in 1926 and was short-lived as Hitler soon broke it off following negative publicity about his relationship with a young girl. Mimi could not handle this and tried to commit suicide but her attempt failed. The alleged relationship with his niece Geli Rabaul lasted somewhat longer but was no success either, whether it was a sexual relationship or not. He neglected her and that led to her suicide in 1931. Hitler seemed to be heart broken and during this period of sorrow, Hoffmann acted as his confidant. He saw his role model slide further down and to help him get over it he decided to introduce Hitler to Eva Braun, a girl working in his photo shop. This relationship also had its ups and downs, in particular Eva’s attempts at suicide in 1932 and 1935. Together with Hitler, she was to meet her end in 1945 by suicide. Hitler badly wanted to retain Eva as his girlfriend but he really began taking her seriously after her second attempt at suicide in 1935. Hoffmann received orders to buy Eva an apartment where she and her sister were to live. This way Hitler could have a relation with her without having her at his side all day.

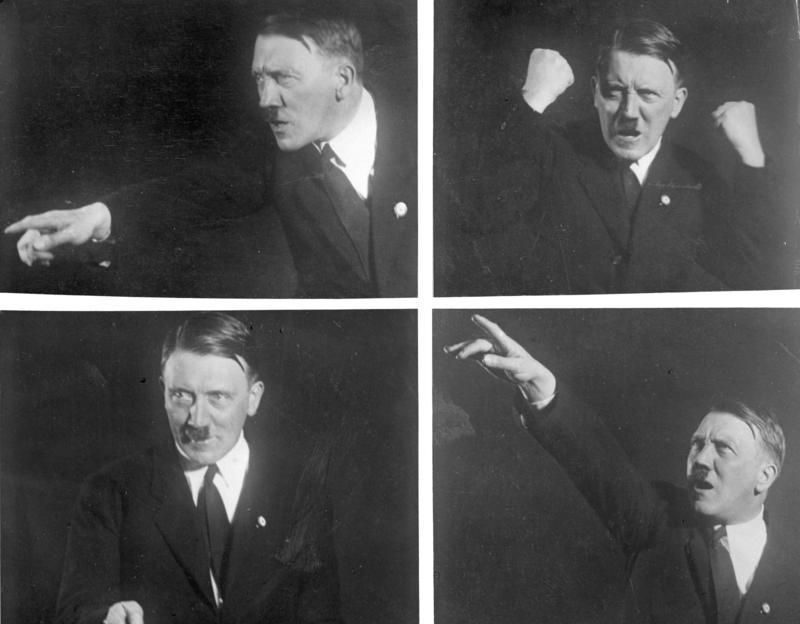

During campaigns for elections in which the N.S.D.A.P. participated, Hoffmann’s propaganda pictures became increasingly more important. Hoffmann was continuously asked to photograph Hitler. A well known series of pictures is from 1929, entitled "Hitler der Redner" (Hitler the orator). In this series, Hitler takes various poses he also used during his speeches. Facial expressions played a large role in these, just like movements of his hands. Propaganda clearly showed two kinds of images: Hitler as a homely father of the people and Hitler with stirring and impressive movements.

Hitler delivered very energetic speeches, stirring up the audiences and making them enthusiastic for his ideas. Every one had to believe in the ideology of the N.S.D.A.P. in order to commit themselves to serving the Reich with full devotion. In order to portray the display of might of the Führer, many pictures were shot showing only Hitler as the great leader. In them he often stands all alone on a pedestal while the people stand admiringly below him. Hoffman shot many pictures like those as well.

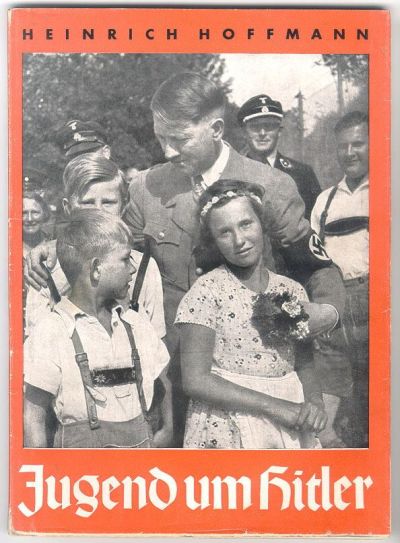

After Hitler had come to power in 1933, the role of propaganda was no less important than before. From that moment on, drawing votes was no longer a priority; Hitler now had to win the trust of the population by pretending he cared deeply for them. In order to enhance this image, Hoffmann shot many pictures of Hitler giving the impression he cared very much for people so there are many pictures showing Hitler dealing with children in a joyous manner while in reality he did not care for children at all.

A famous picture Hoffmann made of Hitler was in 1933, in front of the bars of the cell in Landsberg prison where Hitler had written part of Mein Kampf after his sentencing following the Bierkellerputsch. Hoffmann had also wanted to shoot a picture of Hitler on his release from Landsberg prison on December 20, 1924 but the uniformed guard had demanded Hoffmann should put his camera away as the government had expressly forbidden everyone to shoot pictures of Hitler as he left the prison. Hoffmann gave in and put his camera away. A picture of Hitler’s release would be of immense value for propaganda though and therefore, Hoffmann decided to make the picture anyway but not in front of Festung Landsberg. As soon as Hitler got into the car, they drove to the Landsberger Stadttor where the well known picture was shot of Hitler getting out of the car after he leaves the prison. The location of the picture may not have been the prison but the newspapers used the picture without question. At that time, millions of people must have believed that it really was the prison gate.

Definitielijst

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- Mein Kampf

- “My Struggle”. Book written by Adolf Hitler, outlining the principles of National Socialism.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

Images

Virtues and failings

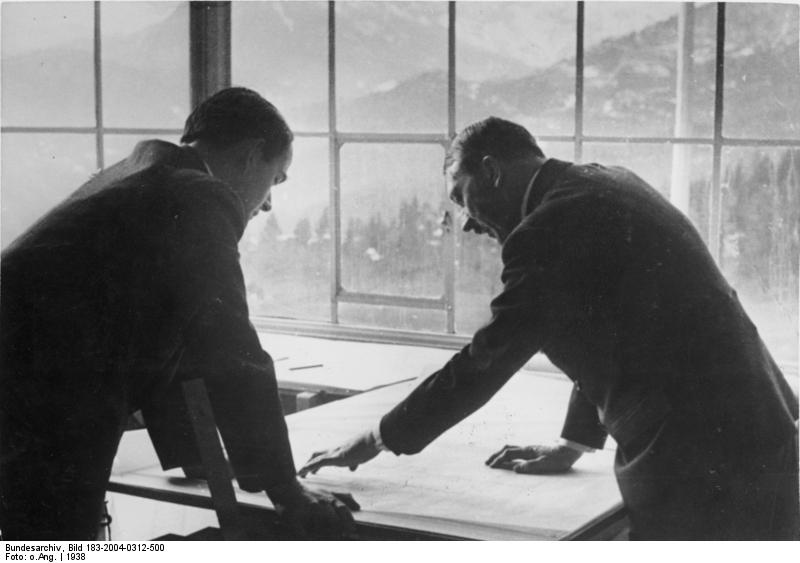

Around 1936, Hoffmann had evolved into a combination of court photographer responsible for propaganda, a successful independent businessman and portrait photographer. In addition he also occupied himself with art. In this connection he was involved in the selection of art for the famous Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung (great German art exhibition) in Munich in 1937. Moreover, he also became a member of the Kommission zur Verwertung der beschlagnahmten Werke entarteter Kunst (committee for handling works of degenerated art), an agency that administered confiscated modern works of degenerated art). Because of his eye for detail he was also allowed to help put together the so-called Sammlung Linz, an art collection that would make Hitler the greatest art collector in the world. The Sammlung Linz consisted of works of art Hitler had stolen from all corners of occupied Europe, destined for a future museum in Linz, the Führermuseum. This way Hoffmann made himself guilty of robbery of art as well. Hoffmann’s company had ceased to be a one man enterprise long ago and had grown into a picture factory. Where Hoffmann had a turn over of 0.7 million Reichsmark in 1933, in 1940 this had increased to 6.6 million and in 1943 this was more than doubled to 15.4 million. The company did not only possess a branch in Munich but also in Berlin and Düsseldorf. After the German territorial expansions, he could open branches in Vienna, Prague, The Hague, Strassburg, Paris and Riga, regular shops by the way.

In addition, Hoffmann owned the largest press agency in Germany and employed well known photographers such as Fritz Schulz, Franz Gayk and his own son Heinrich Hoffmann junior. In addition, he still had many international contacts such as with the New York Times. Being state photographer and chief executive of the company, he made the Hitler portraits and pictures from Hitler’s direct surroundings himself. This way he shot pictures at the Obersalzberg and of Hitler during his travels. In 1945 his company consisted of a massive archive of images and a press department. It was conspicuous though that the largest press department, the one in Berlin employed only 4 photographers out of a total of 66 employees. In short, the money was made by reproducing propaganda material in large volumes. A successful publication of Hoffmann was a picture book entitled "Hitler, wie Ihn keiner kennt" (Hitler as nobody knows him). When this turned out successful, Hoffmann published more picture books. They would cover party meetings, festivities, territorial expansion and the campaigns after 1939, for instance "Mit Hitler im Westen" (In the West with Hitler), always with a prologue, written by a prominent Nazi. Furthermore, those books consisted entirely of pictures with a short caption. Despite the large profits Hoffmann’s company made, the staff complained about the lack of a capable management. Hoffmann showed more interest in art and beer than in leading his company or in company strategy.

Definitielijst

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- strategy

- Art of warfare, the way in which war should be conducted in general.

Images

To Moscow

During World War Two, Hoffmann remained a welcome guest at the Berghof (Hitler’s summer residence on the Obersalzberg in the German Alps), the Reich chancellery in Berlin and the Wolfsschanze (Wolves’ Lair), the Führerhauptquartier in eastern Prussia. His story telling created a lively atmosphere and in Hitler’s court, Hoffmann was some sort of jester who could say much more than others. He was also called the Reichsbetrunkener (state drunk) sometimes due to his alcohol consumption. In August 1939, Joachim von Ribbentrop, German Secretary of Foreign Affairs, received a phone call from Moscow. It was an invitation from Soviet leader Joseph Stalin who was eager to enter into a peace treaty with Germany. This advantageous offer to Germany meant there would be no early Eastern Front. Hoffmann wanted to come to Moscow as well but Von Ribbentrop refused. Hitler did not agree as Hoffmann, being his confidant, would become the messenger of the German delegation. It meant he acted as an intermediary and could transfer messages which could not be funneled through official channels, for instance personal messages from Stalin to Hitler. Von Ribbentrop’s protests fell on deaf ears and so Hoffmann was allowed to travel to Moscow.

Hoffmann hoped to be granted permission to enter the Kremlin, the seat of the Soviet government and so the nucleus of Communism. For the Germans, this was a golden opportunity to watch the workings of the Soviet government from the inside and probably use it for propaganda. Photographers Helmut Laux (personal photographer of Von Ribbentrop) and Hoffmann were granted the desired permission to shoot pictures inside the Kremlin. They were taken to an annex next to the office of Vyacheslav M. Molotov, the Russian Secretary of Foreign Affairs. When a girl servant opened the door to enter, Hoffmann grabbed the opportunity to steal a quick glance of the office. It was a spacious room with hardly more than a desk with a number of phones on it. However, just before the door was closed again, Hoffmann observed something far more interesting, Stalin himself. After having waited a while, both photographers were permitted to enter the room. Signing of the non-aggression treaty had been postponed until the two photographers had entered. When the signing was over, an enormous bang suddenly sounded, followed by a cloud of smoke. The entire German delegation dived for cover, assuming the bang had been caused by a bomb. It was Stalin’s photographer however who was still using an obsolete camera. This camera used magnesium flash powder that had to be lit. This method not only caused a flash but an enormous cloud of smoke as well.

After the signing of the treaty, all those attending went to a dining room where a cozy meal was served. Laux wished to shoot a picture of Stalin but he refused and the result was a picture of Stalin trying to push the camera aside with his hand. Stalin prohibited Laux to ever publish the picture. Hoffmann asked Laux to hand the picture to him and he did. That way Hoffmann had a picture, not too good but a unique one which could remind him and his family of this special day. Later, when the war against the Soviet Union was raging, this picture was to cause an altercation between Hoffmann and Goebbels who wanted to publish the picture. Hoffmann proved to be a man true to his word and did not want the picture to be published, ideal as it was of course for purposes of propaganda. Goebbels became angry and pointed to Hoffmann’s duty as a German not to side with the enemy of the Third Reich. Hoffmann took the argument to Hitler and he sided with his photographer: "If you promised Stalin, you are bound by it. Even the war does not change that."

Definitielijst

- Berghof

- A villa hidden deep in the Alps built at the top of the Obersalzberg near Berchtesgaden. This villa was property of Hitler and centre of the ”Alpenfestung”. The villa has an enormous complex of tunnels with a length of nearly 11 km. From the Berghof the Third Reich was ruled by Hitler and his close companions. Eva Braun, Hitler’s companion, spent a lot of time there.

- Communism

- Political ideology originating from the work of Karl Marx “Das Kapital” written in 1848 as a reaction to the so-called class struggle between the proletariat (labourers) and the bourgeoisie. According to Marx the proletariat would take over power from the well-to-do classes though a revolution. The communist movement aspires an ideal situation where the means of production and the means of consumption are common property of all citizens. This should end poverty and inequality (communis = common).

- Kremlin

- Soviet administrative centre in Moscow.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wolfsschanze

- Headquarters of Adolf Hitler in East Prussia.

Images

Attack on the West

On May 10, 1940, Hoffmann’s was aboard Hitler’s personal train, together with the Führer himself. The train drove in the direction of Hamburg. In Celle, a town south of Hamburg, the train made a stop so the Reichspressechef (State chief of press) could board. After a while Hoffmann noticed they were passing Celle again and he realized the train ride was one great diversionary exercise, meant to lure countries – seeing Germany as a threat to peace - into thinking Hitler had not planned anything yet. The contrary proved true. In the morning, Hitler laid his watch on the table in the carriage and said: "Meine Herren, es ist Viertel nachs sechs genau. Das erste Schuß wird jetzt abgegeben." (Gentleman, it is a quarter past six sharp. The first round will be fired now.) The attack on the West had begun. Around noon, the train stopped in Euskirchen between Cologne and Bonn where waiting cars took them to the first permanent Führerhauptquartier named the Felsennest on the outskirts of the small village of Rodert near Bad Münstereifel. In each headquarters were he was with Hitler, Hoffmann had his own quarters, complete with his own bed and bath room. There also was a radio to kill time. Of course he also went out to with his camera to shoot pictures of officers and soldiers.

Hoffmann was a close confidant of Hitler and among them they could talk about everything and anything. When they had dinner together in the Führerbunker of the Wolfsschanze, Hitler sometimes asked if Hoffmann would like to have a cozy chat with him in order to escape from the daily stress. These chats often took place at night and so Hoffmann often left the Führerbunker after sunrise. He then went to bed immediately while Hitler turned in around noon.

When the German advance in Russia bogged down and the German army was even defeated on various fronts, Hitler became frustrated. In 1943 he often was in his HQ the Werwolf in the western Ukraine near Winnitza and he would not allow anyone around him except Hoffmann. Hence it often happened Hoffmann was Hitler’s only companion at dinner. Self-centered as Hitler was, he attributed all setbacks of the German army to the bad decisions of his generals. Following the defeat of 6th Army at Stalingrad, Hitler and his staff retired to the Wolfsschanze near Rastenburg in eastern Prussia. Even Hoffmann could not stand Hitler’s bursts of anger any longer and he preferred to avoid him as much as possible.

Definitielijst

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Wolfsschanze

- Headquarters of Adolf Hitler in East Prussia.

Images

Berlin under ground

Due to the bombing attacks on Berlin and Munich, Hoffmann moved his picture archive to Winhöring, a small village in Oberbayern. Why specifically this place was selected is unknown. A small village was not often the target of a bombardment hence the archive was relatively safe here. And yet, Hoffmann’s urge for more had not disappeared entirely as becomes evident from an entry in the diary of his not too good friend Goebbels: "This boozer with his bluish-red face ravaged by alcohol had the nerve to propose to Hitler, in the presence of my wife, to appoint him Secretary of Culture. I may have been a good orator but he did know more about art. You would almost believe it. He was probably drunk, as usual."

It became increasingly more difficult to make fresh propaganda. As the successes of the army diminished, Hitler’s isolation and urging not to appear in public anymore grew steadily deeper. It had already started in 1942. This situation made work for the propaganda department and the photographers more difficult. The population wanted to see Hitler more than ever, especially in difficult times. Goebbels voiced as official reason that Hitler occupied himself mainly with his work as commander-in-chief of the armed forces and so had little time to appear in public. Words however did not get Hoffmann’s photographers very far: they had to have pictures. In the course of time, this became all but impossible. Papers like the Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung, the Münchener Illustrierte Presse and the Illustrierte Beobachter attempted to publish pictures of the heroic Hitler. Often pictures were published of Hitler shaking hands, never again a lone Hitler taking all sorts of poses before the camera. The Hoffmann company was still responsible though for pictures of for instance Gauleiter bidding goodbye to Hitler in the Wolfsschanze. Particularly in 1944 the physical decay of Hitler was increasingly difficult to hide, even by editing. In 1942 and 1943 pictures of Hitler among his troops during the Polish campaign of 1939 were presented as new. One of the last pictures of Hitler was probably taken by Franz Gayk. The photo shows the well known scene of Hitler on March 20, 1945, shaking hands of boys of the HitlerJugend in the garden of the State chancellery.

During the last days of he Third Reich, Hoffmann was also present in the Führerbunker beneath the Reich chancellery. At one point in time, Hitler called on Hoffmann to tell him Berlin had gotten too dangerous for Eva Braun. Hoffmann was to take her to Munich in whatever way possible. As to the situation in Berlin, an airplane was almost out of the question and so Hitler asked Hoffmann if there was another possibility. There was, the mail van of Mail Minister Wilhelm Ohnesorge. There still was room to spare so Eva could come along but she had already pointed out she wanted to stay in Berlin with her man and she also rejected Hoffmann’s offer: "No one knows better than you, Herr Hoffmann, that I will stay with Hitler. What will one say when I leave his side in times of need. When it concerns the Führer, I also accept the ultimate consequence."

The day after, Hoffmann went to see Hitler to tell him about the result of his conversation with Eva. Hitler said nothing, made no move, did not even look up. Then the air raid warning sounded and Hoffmann tried to hide. Thousands of thoughts swirled through his head, he said until he realized he had to flee from Berlin before it was too late. He was in a trap that could snap shut any minute. When the all clear sounded he bade goodbye to Hitler, Eva Braun and all the others. He would not have said to Martin Bormann as he had not encountered him any more. A few minutes later, he stood among the ruins on Wilhelmstraße where Ohnesorge’s car was waiting. The car drove off and after a ride of a few hours they arrived in Bavaria. While the car drove on, Hoffmann heard a Wehrmachtbericht stating that Adolf Hitler had fallen during the battle for the Reich chancellery in Berlin. For 22 long years he had been the personal photographer of one of the most important and most hated persons in history and now this man would only live on in his memory.

Definitielijst

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- Gauleiter

- Leader and representative of the NSDAP of a Gau.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- Wolfsschanze

- Headquarters of Adolf Hitler in East Prussia.

Images

After the war

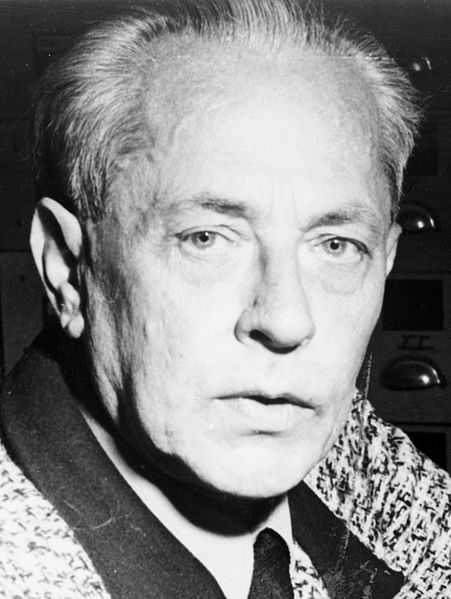

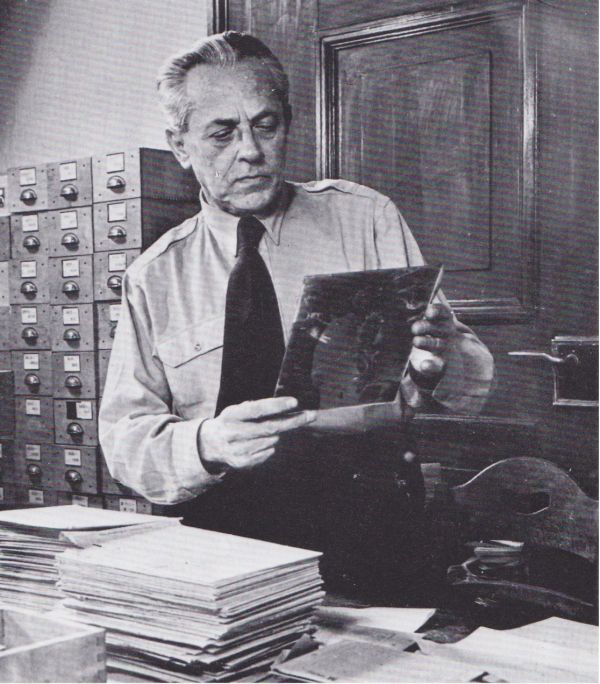

Hoffmann was arrested by the Americans in Oberwösen in the extreme south of Bavaria in May 1945. As he had been a close associate of Hitler, he was imprisoned by the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg in October 1945. Here he had to sort all of his work in aid of gathering evidence for the trials against the war criminals.

In January 1946, the deNazification trials started against the friends and personal photographers of Hitler. These people were divided into categories depending on what kind of role they had played during the war. Having been Hitler’s closest confidant, Hoffmann was placed in the first group with the people who were considered the worst criminals. Initially he was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment but as a result of the confiscation of his fortune, illegally obtained by the Nazi regime, he was released after four years. Consequently, he had to abandon much of his life style. The fortune which was confiscated in exchange for a lighter sentence included everything he owned around 1943. These assets included 6 million Reich mark, houses in Strasburg, The Hague, Amsterdam, Munich and in the rest of Bavaria and of course his paintings.

In 1950, Hoffmann settled down in Epfach, a village 50 miles southwest of Munich. He disputed the confiscation of his fortune for six long years until 1956. At the end of the proceedings, 20 % of his estimated fortune was returned to him. The value of this fortune was hard to determine as Hoffmann possessed many works of art. The origin of these works and their value were hard to determine. All told he received some 350.000 Mark. He continued to live off this money in the vicinity of Munich, the city where he had spent a large part of his life.

Heinrich Hoffmann, personal photographer and confidant of Hitler, passed away on December 11, 1957 at the age of 72. He is buried in the Nordfriedhof, plot M-re-388 in Munich.

Definitielijst

- deNazification

- Post war policy of the allies in Germany to punish Nazi war criminals and to remove known Nazis from positions of power or public service.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

Images

Information

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- HERZ, R., Hoffmann & Hitler, Klinkhardt & Biermann, München, 1994.

- HERZ, R., Zugzwang: Duchamp Hitler Hoffmann, München, Belleville, 2014.

- HEYDECKER, J., Das Hitler Bild, Residenz Verlag, St. Pölten - Salzburg, 2008.

- HOFFMANN, H., Hitler wie ich ihn sah, Winkelried, Dresden, 2011.

- KERSHAW, I., Hitler - Vergelding 1936-1945, Het Spectrum, Utrecht, 2003.