Introduction

Wilm Hosenfeld was an officer of the Wehrmacht during World War Two. He was stationed in Poland from the beginning of the war until Warsaw was captured by the Soviets; he served some 4.5 years in the Polish capital. Here he was confronted with the crimes committed against both Polish and German citizens by his fellow countrymen. He described the atrocities he saw and heard about in his diary, not only full of shame and guilt but he also helped some Jews and Poles to survive.

One of them was Wladyslaw Spzilman, the piano player whose life story was made into a movie by Polish director Roman Polanski in 2002. Thanks to "The Pianist", Wilm Hosenfeld was drawn out of obscurity. Yet, after having seem the movie, we know little more of him than that he was the officer who saved Spzilman. This article is an attempt to change that.

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Wilm Hosenfeld at Thalau, 1944. Source: Hosenfeld Family.

Wilm Hosenfeld at Thalau, 1944. Source: Hosenfeld Family.Prior to the war

Wilm (Wilhelm) Hosenfeld was born May 2, 1895 in the village of Mackenzell in Hessen-Nassau where his father was a teacher. The Hosenfeld family was conservative, Catholic and nationalistic. Wilm became a teacher, just like his father. During his study he made contact with a new German youth movement, the Wandervögel (roaming birds). Its members went out into the countryside in groups to do sports, to walk and to camp. They sang ancient German folk songs at camp fires. Responsibility, friendship, solidarity and brotherhood were the main principles the youth movement stood for. The Wandervögel was a form of protest against the bourgeois society which demanded increasingly more from youngsters. It was a reaction to materialism and urbanization. The ideals of this movement were important for Hosenfeld's personal development. Certain characteristics of the Wandervögel, such as the yearning for a community spirit, the glorification of outside life and the influence of sports and nature were traits he later found in national socialism.

In 1913, Hosenfeld studied at the College of Education in Fulda. When the First World War broke out, he enrolled in the German Imperial Army as a volunteer. In 1914 he joined in battle at Ypre, later on in Lithuania and on the Austro-Hungarian border. In April 1916, he was awarded the Eisernes Kreuz II (Iron Cross). He was injured in 1915 and in 1917 and was awarded the Verwundetenabzeichhen (Medal for the Wounded). In 1917 in Rumania he was so seriously injured he did not return to the front. During World War Two he did not serve at the front either.

After the defeat of Germany in 1918, Hosenfeld was a teacher for some 20 years. From 1918 to 1927 he was employed at a village school in Pessart. Being an advocate of progressive, less authorative didactic views he got into trouble with his colleagues and the administration of the school. A description which clearly typifies Hosenfeld as a progressive teacher is given by one of his sons:"My father was a passionate and cordial teacher", so he says. "In the period after the first World War, when physical punishment was still the rule in education, he treated his pupils completely unconventionally and lovingly. At the school in Spessart, he had first graders sit on his lap when they had trouble spelling. And he always had two handkerchiefs in his pocket, one for himself and the other for the snotty noses of his pupils."

As headmaster of a small school in Thalau, Hosenfeld enjoyed more freedom to voice his didactic ideas. Improving the individual growth and the forming of the character of children were important to him. He worked in Thalau from 1924 until the outbreak of the war.

Definitielijst

- Eisernes Kreuz

- Iron Cross. German military decoration.

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- Iron Cross

- English translation of the German decoration Eisernes Kreuz.

- national socialism

- A political ideology drawn up by Hitler based on the superiority of the German race, the leader principle and fierce nationalism that was fed by the hard Peace of Versailles. National socialism was anti-democratic and racist. The doctrine was elaborated in Mein Kampf and organised in the NSDAP. From 1933 to 1945 National socialism was the basis of totalitarian Germany.

- socialism

- Political ideology aiming at slight or no class differences. Means of production are owned by the state. Evolved as a response to capitalism. Karl Marx tried to substantiate socialism scientific.

Images

National socialism

Hosenfeld married Annemarie Krummacher in 1920. She came from a liberal, Protestant family. Her father was a painter in the colony of artists Worpswede. Just like the ideology of the Wandervögel, the Protestant and pacifistic view on life of his wife influenced Hosenfeld's view on life. Despite these influences, his Catholic background and his progressive didactic ideas, national socialism appealed to him. What he liked most was the promise of friendship and the idea of the people's community. In 1933, he became a member of the SA (Sturmabteilung) and in 1935 of the N.S.D.A.P. (National Socialist Deutsche Arbeiter Partei, or National Socialist German Workers Party). He attended the party meetings in Nuremberg twice. At that moment, he was unaware that part of the norms and values he stood for, were to be attacked or torn down by the Nazis.

It soon dawned on Hosenfeld that the N.S.D.A.P. was not what he had expected of it. Until the outbreak of the war, he drifted further and further away from the party, although he remained a member. First and foremost he criticized the measures that were taken against the Catholic Church. The Catholic Hosenfeld found the Nazis meddling in religious affairs unacceptable. He considered Hitler's uncompromising policy prior to the war a direct threat to peace. He strongly rejected the anti-Semitism of the party. He described the pogroms throughout Germany during Kristallnacht on November 12, 1938 as: "despicable events in the Reich, without law and order, only hypocrisy and lies".

He may well have been a member of the N.S.D.A.P., but Hosenfeld has never been a fanatic Nazi really. "You are not 100% a National Socialist," as was written in an assessment by the school leadership in 1936. A declared reason was that he had criticized Alfred Rosenberg's (Bio Rosenberg) book : "Mythos des 20. Jahrhunderts" the best know book by the party ideologist in which he attacked Jewry and Christianity. Because of their inaccessibility, Hosenfeld also criticized other party officials and SA leaders. Hosenfeld can probably be best described as someone looking for a movement that could unite the politically divided Germany to a strong nation and a solid community. The promises of Hitler (Bio Hitler) and his party must have appealed to him far more than the anti-Semitic rhetoric, the lust for war and other less peaceful goals of the Nazis.

Definitielijst

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- national socialism

- A political ideology drawn up by Hitler based on the superiority of the German race, the leader principle and fierce nationalism that was fed by the hard Peace of Versailles. National socialism was anti-democratic and racist. The doctrine was elaborated in Mein Kampf and organised in the NSDAP. From 1933 to 1945 National socialism was the basis of totalitarian Germany.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- socialism

- Political ideology aiming at slight or no class differences. Means of production are owned by the state. Evolved as a response to capitalism. Karl Marx tried to substantiate socialism scientific.

- Sturmabteilung

- Storm detachment. Semi-military section of the NSDAP. Founded in 1922 to secure meetings and leaders of the NSDAP. Their increasing power was stopped during “The night of the long knives”, 29 and 30 June 1934.

Images

Service in the Wehrmacht

At the time of the German attack on Poland, Wilm Hosenfeld was called up for duty in the Wehrmacht in the rank of Feldwebel (sergeant). He was stationed in Poland from the middle of September 1939 until January 1945. Despite his criticism in the previous years, Hosenfeld seemed to have adopted a positive attitude towards the German invasion of Poland. On September 30, 1939, he still wrote about Adolf Hitler: "Never has a German statesman played a larger role than the Führer". He possibly took a positive attitude to returning the German borders to the situation prior to the Treaty of Versailles. He did not believe it would come to a new world war. Very soon, he would be confronted with the fact that Hitler's ambitions went beyond the situation prior to the Treaty.

Hosenfeld's first posting in Poland was in Pabianice in the vicinity of Lodz where he was involved in the establishment and direction of a PoW camp for Polish soldiers. In December 1939 he was transferred to Wegrów, a village east of Warsaw. He and his battalion stayed until the end of May 1940 in Jadów, not far from his previous station. His last and longest posting was in Warsaw where he arrived in July 1940. He was posted to the Wachbatalion 660, a unit of the Wachregiment Warschau, in the rank of Leutnant. In 1941 he was named sports officer of the Kommandatur in Warsaw. He was promoted to Oberleutnant the same year. As sport officer, he was in charge of the sports facilities in Warsaw that had been confiscated by the Wehrmacht. He was responsible for the organization of the sports education of the occupying forces.

Right from the beginning of his appointment in Poland, Hosenfeld was confronted by the bad treatment of Poles and Jews by his fellow countrymen. When he was stationed near the eastern border in 1939, he witnessed a transport of Poles who had been driven from the Wartheland which had been annexed by Germany. It gave him a feeling of powerlessness and indignity. Hosenfeld felt sympathy for the suppressed Polish population and he stood up for them. According to one of his sons, he had attempted to save a Polish boy from death when he was stationed in Wegrów in the winter of 1939-1940. This boy had been caught in a barn, stealing some hay which had been confiscated by the Germans. The boy was being taken away by the SS and would probably be executed for this small transgression. "My father," so he tells, "threw himself onto the SS man, crying and shouted at him: You cannot murder this child, can you? The SS man drew his pistol, pointed it at my father and threatened: If you don't disappear now, we'll shoot you as well." Hosenfeld's son tells that his father could not stomach this event for a long time. "Two or three years later, he told me, the only member of our family, about this during a holiday.

Definitielijst

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- PoW

- Prisoner of War.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

The Cieciora family

The Polish family Cieciora owes much to Hosenfeld. In the first days of the invasion of Poland, Mrs. Cieciora who was pregnant, was on her way to the PoW camp in Pabianice where her injured husband Stanislaw Cieciora was held. On her way there she met Hosenfeld who asked her where she was going. She explained she was highly worried about her husband. Hosenfeld took her name and promised her, her husband would be back home within three days. And so it happened. Subsequently the Cieciora family and the German officer became friends. Hosenfeld started to learn Polish and even attended regular mass in a Polish church with his new friends and in Wehrmacht uniform

In 1942 and 1943, Hosenfeld held vocational training for soldiers of the Wehrmacht. He received many positive reactions from the soldiers who took part. In the same period, Hosenfeld was promoted to Hauptmann. In that period he also employed 30 Poles as workers in order to maintain the sports facilities. Among them were two Jews using false names: Leon Warm (Warczyski) and Joseph Kuffirski.

Hosenfeld also rescued one of Stanislaw Cieciora's brothers, a Polish priest who was on the run from the Gestapo. Hosenfeld provided him with a safe shelter by hiring him as teacher of Polish, using a false name. The two men became friends. In that way, the German officer made the acquaintance of Koschel, the priest's son in law. After the war, Maciej Cieciora, Stanislaw Cieciora's son, told the Hosenfeld family how their husband and father had also saved Koschel's life. According to Maciej Cieciora, he had probably been arrested in 1943 after German soldiers had been shot in the part of Warsaw where he lived. He and other arrestees would probably be executed by the Germans in reprisal. They were taken away in a truck. Suddenly Koschel recognized Hosenfeld who was accidently walking in the inner city. He waved at him desperately which prompted Hosenfeld to take action. The German officer made the truck stop and yelled in a harsh tone to the driver he needed a man. He selected Koschel "at random" and he was allowed to get of. That was his rescue.

Definitielijst

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- PoW

- Prisoner of War.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Uprising in Warsaw and Wladyslaw Szpilman

The courses organized by Hosenfeld until the spring of 1944 were well attended. That summer, German forces in Warsaw were rudely shaken by a revolt of the Polish Home Army that erupted on August 1 and lasted until October 2. It ended in defeat for the Poles. Between 16,000 and 20,000 Polish resistance fighters and some 150,000 civilians lost their lives against some 160,000 German soldiers. After the revolt, the Germans destroyed a large part of the city. Hosenfeld and the staff of the Kommandantur were locked in by the rebels for 10 days. Thereafter he was given a new function as deputy intelligence officer. He interrogated civilians and rebels. He had a discussion with the commanding general to grant the rebels the status of prisoners of war but in vain.

Shortly after the uprising, Hosenfeld met Wladyslaw Szpilman. Szpilman was a Jewish piano player who had worked for the Polish radio before the war. He had survived the evacuation of and the uprising in the Warsaw ghetto as well as the uprising of the Polish Home Army. In November 1944 he had found shelter in an abandoned house in the desolate city. After he had been hiding in the attic for two days he searched the house for food. "I was so completely focused on my search," Szpilman writes in his book, "I heard the voice only when it said right behind me: What are you doing here?" Leaning against a kitchen cupboard stood a tall, elegant German officer, his arms crossed on his chest. "What are you doing here," he asked again. "Don't you know the staff of the Warsaw Kommandantur is occupying this house at the moment?"

Szpilman was extremely lucky as the German officer who found him during his search for food was Wilm Hosenfeld. After Szpilman had surrendered, Hosenfeld made it clear to him he wasn't going to hurt him. He asked what his profession was and when Szpilman answered he was a piano player, Hosenfeld invited him to play a piece on the piano in the house. Szpilman played the Nocturne in C minor by Chopin. Thereafter the officer advised Szpilman to leave the house. "I will take you to a village outside the city. You'll be safer there." Szpilman answered emphatically he could not leave. "Just now he seemed to understand the real reason why I was hiding between these heaps of rubble," Szpilman writes. "He became very nervous. You are Jewish, " he asked. "Yes." "Indeed, you can't leave in that case."

Subsequently Szpilman showed his hiding place in the attic. Hosenfeld discovered a floor above the attic where Szpilman could hide himself far better. He also helped to find a ladder for him he could pull up when he was upstairs. "After everything was over and done with," Szpilman continues his story "he asked me if I had something to eat. I answered no as he had surprised me during my search for food. Well, all right, he said hastily as if he was ashamed about his raid, I shall bring you some food. Only then I dared put a question myself. I couldn't hold out any longer: Are you German"? He turned red and he shouted angrily as if I had insulted him with my question: Yes, I am a German. And after all that has happened I feel deeply ashamed."

A few days later Hosenfeld brought a few loaves of bread and jam to Szpilman. He also told him he had to hold out for a few more months. The Soviet army was closing in and "anyway, this whole war will end in the spring at the latest." In the middle of December, Szpilman saw his savior for the last time. Szpilman: "He brought me a larger supply of bread than before and a warm blanket. He told me he and his unit were leaving Warsaw and that in any case I should not lose hope as the Soviet-Russian offensive could be expected any day now." In closing, Szpilman told him his name. "You haven't asked me for it," Szpilman describes in his book what he had said hat day: "but I would like you to remember it. Should something happen to you and if I can help you in any way, remember this: Szpilman – Polish radio."

Wladyslaw Szpilman survived the war and immediately described his experiences in a book entitled "Smierc Miasta" (Death of a city) in 1945. During the Cold War, publication of this book in Poland was thwarted by the Communist regime. In 1998 the book was published in German and made into a movie entitled "The Pianist" in 2002 by Roman Polanski. Wladyslaw Szpilman did not live to see his live story on film as he passed away in Warsaw, July 6, 2002.

Definitielijst

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Images

Wladyslaw Szpilman, the best known person who was rescued by Hosenfeld. Source: http://www.szpilman.net.

Wladyslaw Szpilman, the best known person who was rescued by Hosenfeld. Source: http://www.szpilman.net. Szpilman at the piano. Source: http://www.szpilman.net.

Szpilman at the piano. Source: http://www.szpilman.net.Prisoner of War and demise

On January 17, 1945, Warsaw was captured by the Red Army and Wilm Hosenfeld was made a prisoner of war. In his book, Wladyslaw Szpilman tells how he found out, through a violinist friend, that his helper had become a PoW. On his return to Warsaw this colleague, so Szpilman writes, walked along a barbed wire fence behind which German PoWs were being held. A Wehrmacht officer spoke to him and asked for Szpilman of the Polish radio but the German, Wilm Hosenfeld, forgot to mention his own name. Despite Szpilman not knowing his name, he immediately tried to track down his helper in 1945 but to no avail. When he arrived on the spot where his colleague had been speaking to the German officer, the PoW camp had already been abandoned.

Until 1949, Szpilman heard nothing about his savior until the Jew Leon Warm contacted him. Warm was one of the Jews who had been employed by Hosenfeld as a stadium keeper under a false name. According to one of Hosenfeld's sons, he had visited Mrs Hosenfeld on November 14, 1950. She still lived in a part of the former staff accommodation of the village school in Thalau. That way Warm discovered his helper was still alive. Mrs. Hosenfeld showed him a picture postcard from her husband dated July 15, 1946, showing a list of people he had saved. No. 4 on the list was Wladyslaw Szpilman. Leon Warm found the address of the piano player and went to see him. That way, Szpilman finally found out the name of his helper.

In order to try and get Hosenfeld released, Szpilman went to see Jakub Berman, chief of the Politburo of the Polish Communist Party and Stalin's (Bio Stalin) representative in Poland. Szpilman has always felt ashamed about this because in his book he describes Berman as "a criminal decent people in Poland do not talk to." Szpilman explained to him that Hosenfeld had not only helped him but others as well. "And that terrible Berman was friendly to me," so Szpilman writes in his book, "and he promised to do his best for me. A few days later he even went to see us at home: alas; nothing can be done." He said: "If this German would still be in Poland we could be able to get him out. But our comrades in the Soviet Union will not release him. They say this officer belonged to a department which was also engaged in espionage – then we Poles can do nothing, our hands are tied."

According to Wolf Biermann, author of the essay "Bridge between Wladyslaw Szpilman and Wilm Hosenfeld, built from 49 remarks" Hosenfeld was "brutally tortured during his imprisonment as the Soviet-Russian officers considered his remarks about saving Jews especially suspicious lies." In 1950, the Soviets sentenced him for being a war criminal but he appealed his sentence. That year, he was transferred from Minsk to a PoW camp in Stalingrad. As early as 1947 he had suffered a stroke and in Stalingrad he was admitted to hospital after several more strokes. "He lived half dazed as a beaten child that does not understand why it has been beaten," so Biermann writes. In 1951 he was told his appeal had been turned down. He passed away on August 13, 1952, about a year before Stalin's death. Biermann: "He died, totally broken mentally"

Definitielijst

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- PoW

- Prisoner of War.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Diary entries and letters

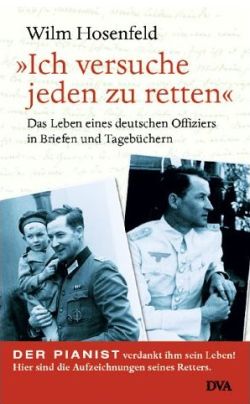

In 1998, one of Hosenfeld's daughters found a case in the attic containing over 600 letters from her father to her mother and many other documents, such as letters to his children, picture postcards from the time he was a prisoner of war, diaries and exercise books filled with notes. This material was compiled by Thomas Vogel in a book, published in 2004, entitled "Ich versuche jeden zu retten. Das leben eines Deutschen Offiziers in Briefen und Tagebüchern" (I tried to rescue everyone. The life of a German officer in letters and diaries). Previously, parts of the diary kept by Hosenfeld in Warsaw had been published in recent copies of the book by Wladyslaw Szpilman, mentioned before. The diary entries strengthen the image of the idealistic, helpful German officer who distinguished himself from the average German soldier by his humane attitude and compassion during World War Two. The major subjects he frequently describes are his growing aversion towards National Socialism, Hitler and the war the extermination of Jews and the way he looked at it from a Christian point of view.

"Why did it have to come to war?" Hosenfeld wrote on September 1, 1942. "People must be shown once where their godlessness leads them to. Initially, Bolshevism has murdered millions in order to achieve a so-called new world order. It could only do this because it has alienated itself from God and the Christian belief. Now, National Socialism does the same in Germany: it prohibits people to have a religion, educates youth without religion, wages war against the Church, confiscates its possessions, suppresses those who think differently, lowers the free individualism of the Germans to frightened, subdued slaves. There are no commandments anymore – you shall not steal, kill, lie – if it goes against one's own interest. From this denial of the holy commandments emerge all other immoral appearances of greed, illegal enrichment, deceit, sexual unbridledness resulting in infertility and downfall of the population."

Hosenfeld also mentioned the Holocaust frequently in his diary notes. On April 17,1942 he wrote about the gas chambers in Auschwitz and on July 23 about an action to exterminate Jews. "Stories circulate about Lietzmannstadt (Lodz) and Kutno to the effect that Jews, men, women and children are being poisoned in mobile gas chambers, that the dead are being undressed, thrown into mass graves and their clothes sent to textile factories for further use. Now they are apparently on the verge to empty the Warsaw ghetto in a similar way," When he wrote about Kutno, Hosenfeld must have meant Kulmhof – Chelmno in Polish – the first extermination camp of the Nazis where some 32,000 people, mainly from the ghetto in Lodz, were exterminated.

As Hosenfeld assumed correctly, Jews from the Warsaw ghetto were deported from July 22, 1942 onwards. They were taken to extermination camp Treblinka where between 870,000 and 925,000 people have been killed. Hosenfeld already mentioned this extermination camp in 1942 in his diary. On June 16, 1943, after the uprising in the Warsaw ghetto, he wrote: "Countless Jews have been killed, without reason, without usefulness, without thinking. Now the last remaining Jewish inhabitants of the ghetto have been exterminated. The entire ghetto was one large burning heap of rubble. In this way we aim to win the war, we animals. With this horrendous mass murder of the Jews, we have lost the war. We have brought upon ourselves an ineradicable shame, an irrevocable curse. We are not worthy of mercy, we are all accessories to these crimes."

The rumors Hosenfeld heard about the Holocaust were not always correct. For instance, he wrote on July 25, 1942: "Somewhere, not far from Lublin, … buildings were erected containing rooms which can be electrically heated just like in a crematorium. The unlucky victims are herded into these heating rooms and subsequently burned alive." Heating chambers like that have never existed. In Lublin however, extermination camp Majdanek was located where the victims were gassed with Zyklon B in gas chambers. On September 6, 1942, Hosenfeld also described a "mobile shed" in Treblinka in which, according to him, people were gassed but this has never existed either. In Treblinka, people were gassed with exhaust fumes in fixed gas chambers. The only mobile gas chambers have been the gas vans deployed in Chelmno, by the Einsatzgruppen and on other locations. Despite these substantive errors, one can draw the conclusion that Hosenfeld was pretty well informed about the extermination program of the Nazis. The excuse "Ich habe es nicht gewußt"(I did not know about it) surely does not apply to him.

The last entry in the diary is dated August 11, 1944. Hosenfeld describes the order Hitler had given to raze Warsaw to the ground. He called it: "the failure of our policy in the east. With the destruction of Warsaw, we are erecting the final monument for this policy." Prior to the capture of the city by the Soviets, Hosenfeld sent his exercise books filled with notes to his family in Germany. He did this through Wehrmacht mail. He ran an enormous risk doing so as the explosive content of his writings could have earned him a death penalty. However, his mail reached Germany without a hitch. As late as 1998 it was rediscovered after his wife Annemarie had passed away.

Definitielijst

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- National Socialism

- A political ideology drawn up by Hitler based on the superiority of the German race, the leader principle and fierce nationalism that was fed by the hard Peace of Versailles. National socialism was anti-democratic and racist. The doctrine was elaborated in Mein Kampf and organised in the NSDAP. From 1933 to 1945 National socialism was the basis of totalitarian Germany.

- Socialism

- Political ideology aiming at slight or no class differences. Means of production are owned by the state. Evolved as a response to capitalism. Karl Marx tried to substantiate socialism scientific.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Images

Rightheous among the Peoples

Yad Vashem is Israel's national Holocaust monument honoring not only Jewish victims and heroes of the resistance but also non-Jewish helpers from the Second World War. Those non-Jewish helpers are called Righteous among the Peoples. Until halfway into the 90s, trees were planted for these persons. In 1996 a special memorial garden was laid out where the names of all helpers can be found. New names are added every year. When this article was written, 443 Germans have been awarded this title by Yad Vashem. Hosenfeld is not one of them, despite efforts by people such as Andrzej Szpilman, Wladylslaw Szpilman's son.

At the publication of the German version of the book by Wladyslaw Szpilman, Wolf Biermann wrote about Yad Vashem: "I will try to have a tree planted for Hauptmann Wilm Hosenfeld, irrigated with water from the river Jordan. And who to plant it? That is quite clear: Wladyslaw Szpilman. And his son Andrzej will help him." This intention failed however, not only because Wladyslaw Szpilman passed away in 2000 but also because the request to recognize Hosenfeld as Rightheous among the Peoples was rejected. "The decision was based on the Soviet sentence because he had had to interrogate Polish rebels at the time of the uprising in Warsaw in 1944," his grandson Friedrich Hosenfeld explains in an e-mail. "Efforts are being made to start a new procedure at Yad Vashem, taking into account the fact he has helped numerous Poles and Jews. Therefore he must be rehabilitated in Russia first and then in Byelorussia.

On February 19, 2009, Wilm Hosenfeld was belatedly and posthumously awarded the title Rightheous among the Peoples by Yad Vashem. This because he saved Szpilman and Leon Warm. On June 19, 2009, the award was officially received by Detlev Hosenfeld, one of Wilm Hosenfeld's son. Also present at the investiture in the Jewish Museum in Berlin was Halina Szpilman, Wladyslaw's widow.

Read more about the decorations of this person on TracesofWar.com

Definitielijst

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Yad Vashem

- Yad Vashem is Israel’s national Holocaust memorial where in addition to Jewish victims and resistance heroes, also non-Jewish helpers of Jews during the World War 2 are being honoured. Those non-Jewish are called the Righteous Among The Nations. Until the mid 90’s trees were planted for these rescuers. In 1996 a special remembrance garden was established displaying all of the names of the helpers. Every year new names are added.

Images

Information

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- SPECTOR, S. & ROZETT, R., Encyclopedie van de Holocaust, Kok, Kampen, 2004.

- SZPILMAN, W., De pianist, BZZTôH, 's Gravenhage, 2003.

- VERHOEF, C., Wilm Hosenfeld, Recensie: ‘Ich versuche jeden zu retten’ – Het leven van een Duitse officier in brieven en dagboeken, Bulletin van de Tweede Wereldoorlog, nr. 9, pag. 123 t/m 130, Aspekt, Soesterberg, 2006.

- Lebensdaten von Wilm Hosenfeld, short biografic overview, made available by the Hosenfeld family.

- E-mail with Mr. Friedel Hosenfeld, the grandson of Wilm Hosenfeld.