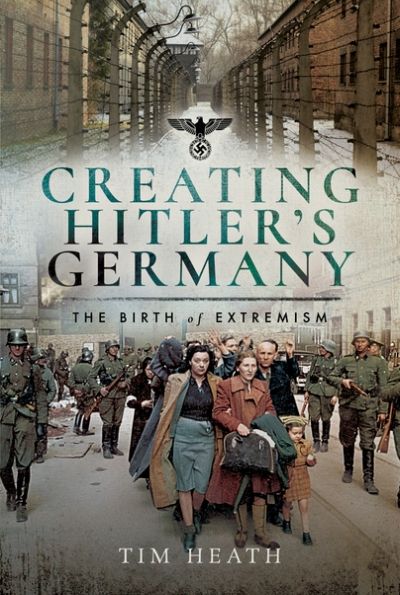

| Title: | Creating Hitler's Germany: The Birth of Extremism |

| Writer: | Heath, T. |

| Published: | Pen & Sword |

| Published in: | 2019 |

| Pages: | 224 |

| Language: | English |

| ISBN: | 9781526732972 |

| Description: | Creating Hitler’s German tells the story of the German defeat in 1918 and 1945 and how Hitlers megalomania resulted in an international tragedy. Based on primary sources Tim Heath sheds a new light on the course of the First and Second World War and which role social and political factors played in this. Through interviews, correspondence through letters and memoires the reader follows a number of individuals whose lives would never be the same again due to the German aggressor. Tim Heath succeeded telling personal stories without losing sight of the historical course of the start of the 20th century. One of these stories is that of Werner and Hilde Kohlman, a Hamburgian working class couple. One day they would marry and have a happy life, at least that is what they thought. Fate decided otherwise. On 28 June 1914, the day of archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary’s assassination, changed their lives forever. A combination of personal circumstances, uncertainty and sense of duty led to Werner voluntarily signing up for the German army in 1915. The gravity of the First World War becomes clear for the first time in the censored letters Werner exchanged with his beloved Hilde during his military service. In these letters Werner described how the German ground forces was approaching the French and British lines and how horrific the suffering was at the frontline. Nevertheless, he also wrote the war in the trenches could be quiet sometimes. So quiet, that one of Werner’s companions one day decided to take a look above ground without a periscope. Just before an enemy sniper hit him fatally, he said: "It’s so peaceful here, it seems just like we’re not at war at all, right?" Werner’s adventure as infantryman would end not long after. In 1916 he found himself in a storm of artillery fire near Verdun. He got hit by an exploding grenade, probably from a heavy howitzer. Although the war came to an end at 11 November 1918, Werner would remain cripple for the rest of his life. Next to a clear storyline Heath manages to paint a very lively and detailed image of the Second World War. The book first approaches the conflict geographically before sketching the chronological course of the war. The country discussed first is Poland as victim of the German Blitzkrieg.About the attack on Poland on September 1st, 1939 Heath tells the Polish air force was outclassed by the Luftwaffe both on technology and strategy. The Polish resistance, however fanatic, could not withstand the power of the Messerschmitts and Stuka dive bombers, nor the coordinated invasion of the German ground troops. According to the German veteran Karl Heinz Lutz they did not worry about Poland whatsoever. France, that was the real enemy. Primarily the paramilitary Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz made itself guilty of war crimes in Central- and Eastern Europe, and supported the Gestapo, the Schutzstaffel (SS) and the Sicherheitsdienst (SD). They actively fought against the Polish. Some victims were buried alive, mothers and children were shot dead together. Heath secured a report of a German soldier about such an incident in the Polish city Swiecie. In it was written: "The first thing I remember is rats eating from dead bodies […]. It was a pitiful view, those small bodies of children shot dead." According to Heath many members of the Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz are still alive. He wonders whether they regret their actions. Because of this the war suddenly gets really close.Not only the Polish, but also the British offered great resistance against the Germans. In response to the Nazi-aggression in Europe the 1938 British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was prepared for a potential war with Germany in France and the Low Lands. The German invasion of France (Fall Gelb) started at May 10th, 1940. Here as well the Luftwaffe charged first, followed by German tank and infantry units. Gefreiter Karl Lutz fought against the French at the Maginot line, a series of concrete fortifications, obstacles and weapons the French already had installed from 1930 onwards to discourage the Germans. Yet instead of crossing this line, the Germans went around it. Lutz wrote regarding this that he would forever remember June 25th, 1940, the day the Germans defeated the French. The fact that the Germans had breached the Belgian neutrality was none of his concern. England too came under heavy fire. Hitler knew he had to defeat the British to make his ambitions come true. However, the new prime minister of Great-Britain, Sir Winston Churchill, would not make any concessions. On July 10th, 1940 the Battle of Britain started, an invasion consisting of four phases of airstrikes. Because of the abundance of information on this topic, Heath chooses to not go deeper into the subject. Instead, he displays a few eyewitness reports. One of them is from petty officer Karl Retschild, a German Heinkel air gunner. When he flew over the city after the bombardment on Coventry and saw the German-caused conflagration, he thought: "God, help those people down there." Despite death and destruction in England, the British kept fighting. However, no one was prepared for the offensive of 1944-1945 and the Vergeltungswaffen. Another case Heath discusses is the German occupation of Norway that started on April 9th,1940. The country appeared particularly important from a strategic point of view for the Germans and was then taken over by a sort of fake government: the Reichskommissariat Norwegen. Indeed, Norway became the most fortified country during World War Two, with a ratio of one German soldier for every 8 Norwegians. Nevertheless, the resistance of the Norwegian population remained fierce. This appears, among other things, from the intriguing story of Peter Weiss, a German soldier who in 1940 was stationed around Oslo. Peter got to know ‘Ingrid’ there and fell hopelessly in love. This love would not last long though. Just like the war in the West this book also covers the Eastern front quite accurately. Still, the emphasis in this chapter is mostly on reports and eyewitnesses as well. Despite the Molotov-Ribbentropp act Hitler decided to invade the Soviet Union in 1941. Operation Barbarossa was an attack the Soviets did not anticipate. However, while it would become the biggest land invasion in the military world history in terms of both material and manpower it remained a big gamble. Many different factors indeed played a role in the course of the war, Heath writes. As the invasion progressed, the weather conditions turned bleaker and the battle more brutal. This is also apparent from a memoire of Waffen-SS soldier Herbert Shiller. No one was spared by his section. In Russia the role of Alexander Kohlman, son of the previously mentioned Werner and Hilde Kohlman, becomes clear. He was sent to the Eastern front as a soldier of the Waffen-SS, where he kept a diary. In it, he wrote among other things that his unit was moving towards a great battle. Alexander was referring to the Battle of Kursk, where Alexander’s SS-Panzer Division ‘Das Reich’ was part of a tank battalion. Its purpose was to break through the Soviet lines at the latitude of Prokhorovka. Alexander was convinced they would end up as the great victors. However, Alexander’s tank was severely damaged by anti-tank weapons and would never get that far. The great battle he wrote about resulted in a great defeat. Many of his friends would never return home. One subject the book thematically covers is the holocaust. Heath does this by focusing on what was happening in camps such as Bergen-Belsen, Buchenwald, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka and other locations of mass destruction. According to Heath most of the camp personnel worked in such camps out of free will. Karl, a former camp guard, was one of them. About the murdering of the prisoners he told it did not matter whether you killed them with your own hands, with your shoes or a weapon, or by taking their food or water. In the end every method ended with death and that is wat counted. At the same time Heath looks at the subject from the other side as well. Katrina Roth, a German woman who briefly worked at Auschwitz, involuntarily became eyewitness of the horrors of the holocaust. She too was scarred for life. With the story of Katrina the reader is reminded that normal Germans became victim of the concentration camps as well. Moreover, not only Germans were perpetrators: the Soviets too were guilty of destroying many lives. Still, especially the story of Soviet major Lieniev Ivavanhovich left a deep impression. He encountered the concentration camp of Treblinka after the Germans had ‘destroyed’ it. They left it behind as if nothing had ever happened there. According to Ivavanhovich the Germans thought they had tried hard to conceal the camp. However, he found they did not manage to hide at least one thing, which was the smell of death. The book ends in 1945, when the big suffering is finally over. In the last chapter Heath dives deeper into the moment when Germans start losing territory in favour of the Red Army. In this period German soldiers as well as citizens across Germany were killed. Heath here questions the definition of genocide and ends the book by drawing a comparison between the holocaust and the bombardment of Dresden in February 1945. He asks whether a crime is less criminal when the scale is smaller. With this the book may have come to an end, but the reader is left with plenty to think about. Creating Hitler’s Germany makes clear which internal and external elements were responsible for the increase of extremism in Germany in the period 1914-1915. Heath knows how to engage the reader by finding a balance between the general narrative of the First and Second World War and personal stories. As a result, the author creates a nuanced image without repeating himself even once. The book is clearly written for a wide audience and reads easily. |

| Rating: |     Very good Very good |

Information

- Translated by:

- Thijs de Veen

- Article by:

- Claire van Proemeren

- Published on:

- 01-11-2020

- Feedback?

- Send it!