Introduction

Three women walking ahead of us, their handcart has broken down. One of them slips and falls. I help her to her feet. She has hurt herself and cries and suddenly she yells: "I want to go to my children!" It becomes too much for the other two as well. We can't stand the misery any longer.'[1], an inhabitant of Zwolle recalls one of the hunger trips he made during the Hongerwinter (hunger winter).

In the fall of 1944, the Dutch were convinced their liberation from German occupation was imminent. Instead, they were confronted with a severe winter and a critical shortage of fuel and food which would claim thousands of lives and would generally be known as the Hongerwinter.

Definitielijst

- hunger winter

- Term for the winter of 1944-1945 in occupied Holland. The heavily populated west of the Netherlands had not yet been liberated. Due to stagnation of coal transports, food shortages and a very cold winter many people were hungry and died.

Previous history

Food distribution in the Netherlands

Before the war, the Netherlands enjoyed one of the highest standards of living in (Western) Europe. For instance the diet of an average worker contained 3,000 kcal in 1936. As the Dutch population had grown with over two million during the interbellum and the increase of agricultural products lagged behind at the end of the 30s, the Dutch government began to worry about food distribution during a possible future war. Therefore, the Rijksbureau voor de Voorbereiding van de Voedselvoorziening in Oorlogstijd or State Office for Preparation of Food Distribution in war time, in short RBVVO was established. This office was headed by the agricultural engineer and government commissioner of arable farming and animal husbandry Stefan Louwes. The office developed a new system of food distribution in which the government played a regulatory role and as to production much freedom was granted to the sectors involved. An important element in this plan in case of a possible war, the Dutch agricultural industry should focus more on self-sustainability meaning for instance that less grain should be used for cattle feed and more food, rich in carbohydrates, be grown. Before the war, rationing of a number of products was introduced. Not so much because of shortage but to test the system. The distribution proved quite satisfactory.

After the Netherlands had been captured and occupied by the Germans in May 1940, Louwes remained in charge of the RVVVO, now called the Rijksbureau voor de Voedselvoorziening in Oorlogstijd (RBVVO) or State Office for Food Supply in Wartime. He was subordinate to Hans Hirschfeld, Secretary-general of Economic Affairs. During the remainder of the war, these two officials would play an important role in the Dutch food supply and the negotiations with the Germans on this subject.

Before the war, the Dutch government had already stockpiled large quantities of grain, fat and cattle feed. These were put to good use after the occupation of the country. Nonetheless, in order to achieve more self-sustainability, it was necessary to decrease the number of pigs and poultry in order to make more food available for human consumption. The decrease of the export was an advantage, making twice as much vegetables available for the Dutch market. About the distribution, Louwes said: 'De voeding van het Nederlandse volk moest kwalitatief worden verlaagd om kwantitatief enigszins voldoende te blijven.' (Food for the Dutch population had to be decreased in quality to make it more or less acceptable in quantity).[2] Until September 1944 the distribution system functioned well. The food was even distributed more fairly than before the war.

Despite the Dutch having confidence in the system and adhered to the rules, they were not satisfied with the distribution. They couldn't buy at random any longer. Animal products like eggs, meat and dairy were replaced by potatoes and vegetables. The longer the war lasted, more and more scarce luxury products like coffee and tea were being replaced by surrogates. Distribution also entailed a huge amount of administrative work. From the introduction of the 'potato card' in April 1941 onwards, all food stuff was rationed except fruit, vegetables and fish. Later on, fish would be rationed as well and would be hard to get during the entire war mainly as the German had put a ban on fishing on the Noordzee and because many fishing vessels were being confiscated.

The Dutch started looking for means to supplement their - in their view - meagre rations. This way, a black market came into being where food and ration cards were exchanged for money and/or goods. Creation of a black market is often caused by a shortage of food. Compared to other countries, the black market in the Netherlands would retain a limited extent until 1944 though. An estimated 20 to 25% of the agricultural products ended up on the black market.[3] In most other occupied countries like Belgium and France, this percentage was considerably higher right from the beginning of the war.

Agricultural historian Gerard Trienekens states that up to September 1944 the Dutch war diet remained at a steady level as to quantity and quality. Contrary to what was claimed during and after the war, it is also not true that Dutch food stocks were systematically being pillaged by the Germans. Research by Trienekens shows that only 3.3% of the Dutch agricultural products had been shipped to Germany in the years 1943 and 1944.[4]

Crazy Tuesday

In August and early September 1944 the Allied armies advanced rapidly through France and Belgium and it only seemed to be a matter of time before the liberation of the country would begin. On September 4, Reichskommissar Arthur Seyss-Inquart proclaimed a state of siege. The next day, which would later become known as Dolle Dinsdag or Crazy Tuesday, panic erupted among the Germans and the Dutch National Socialists. They fled in their masses. German military confiscated fuel and food supplies and means of transport. According to De Zwarte: 'desintegreerde wat van de economie en het gecentraliseerde voedselsysteem overbleef vrijwel direct.' (Whatever was left of the economy and the centralized food distribution disintegrated almost immediately'.)[5] As the situation of the war deteriorated and troubles with transport increased, a growing number of people started to work around the system as from September 1944.

The agricultural sector also faced other problems. Within the framework of defense against an expected Allied invasion, nearly 20,235 acres had been inundated by the Germans. During razzias (round-ups) 120,000 men had been picked up. Many other workers had gone into hiding. This caused problems for the harvest. From September onwards, agricultural areas and coal mines in the south were out of range due to the Allied advance. Fishery and shipping also suffered from a growing number of limitations imposed by the Germans such as confiscation of fuel and vessels.

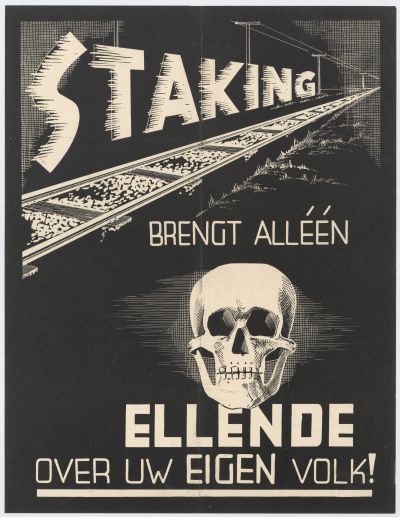

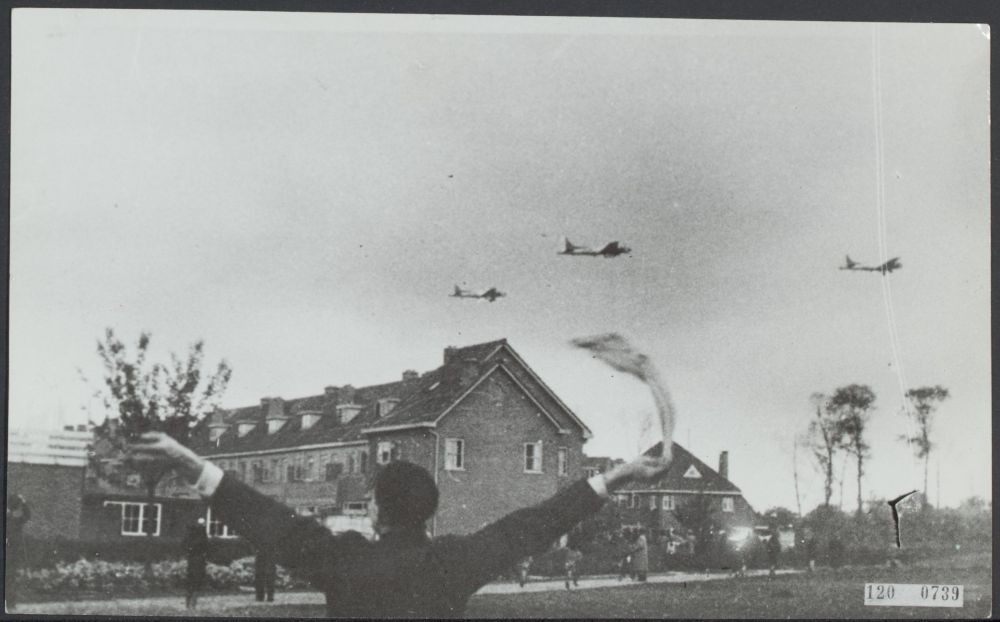

Railway strike

On Sunday September 17, 1944, the Allied supreme command asked Pieter Gerbrandy, prime minister of the Dutch government in exile, to call a national railway strike in support of Operation Market Garden. This was aimed at thwarting the German supply and transport of V- weapons to the coast. Initially, not all railway personnel adhered to the call from London. This was also caused by the fact that the management of the strongly hierarchical company hadn't given any orders for the strike. Towards the end of the week though, all 30,000 employees had laid down their work.

Prior to the call for strike, government officials in London had voiced their doubts about the strike. After all, it would also thwart the supply of the Dutch cities and people were afraid of German reprisals. When Dutch journalist and writer Loe de Jong discussed this with Gerbrandy, the PM replied: 'Don't worry, Friday we'll be in Amsterdam.'.[6] It soon became clear though that the airborne operation would not trigger the planned liberation of the occupied Netherlands.

The first day, the Germans were not overly impressed by the strike. They assumed this would only cause problems for the Dutch population and the resistance. The Germans themselves faced limitations as well though as trains didn't run anymore. This problem was solved soon by having 5,000 railway personnel come over from Germany. The strike did cause enormous delays in the delivery of food to the large cities in the western part. After all, 60% of the coal and perishable products were delivered by train. The railway strike also coincided with the start of the harvest of potatoes so nothing could be transported.

Delivery by road also caused problems due to the Germans confiscating trucks and a shortage of fuel. In addition, the Germans had prohibited stockpiling large food supplies as in case of an Allied invasion, these could fall into enemy hands. The RBVVO had kept food apart though but this was stored in the northeastern provinces so it couldn't be transported to the west. These provinces counted 4.3 million inhabitants of which 2.6 million in the large cities. The agricultural sector here produced only sufficient potatoes, grain and dairy for a few weeks.

The Germans called on the Dutch to go back to work as famine would be imminent. This call had no result though. On September 27, Seyss-Inquart imposed an official ban on transport of food to the west in reprisal of the strike. German confiscations continued nonetheless, communication lines were broken and massive destruction was inflicted to the ports of Amsterdam and Rotterdam.

After the war, Louwes stated about the situation that arose at the end of September: 'Van deze datum af dateert een bittere strijd om ons naakte bestaan, van hongersnood in optima forma.' (From this day on a bitter fight starts for our naked existence, of famine in optima forma.'[7] On September 27, 1944, a message was sent to London via illegal channels that Amsterdam was left with bread for only five days and potatoes for three weeks. The Dutch government considered lifting the strike and started negotiations about this with the Allied supreme command. This command indicated that trains in the west were allowed to run but not in the German border area, the region east of the line Arnhem-Apeldoorn. According to the minister, this was an unfavorable solution, also because it was feared the Germans would start reprisals against the railway personnel in hiding when they resumed their work. On October 2, 1944, a speech from London indicated that the railway strike should continue. One of the reasons was that transport of coal was no longer possible since Limburg had been liberated by the Allies, another one was that railway personnel would be subjected to air attacks as soon as they started work again. Also, if the trains were to ride again, the Germans would ransack the country even more.

Gerbrandy meanwhile attempted to draw more attention to the fate of the Dutch population in order to accelerate the liberation of the country. Initially, this had little effect. British PM Winston Churchill refused to send food to occupied Holland because this would only benefit the Germans. Moreover, the Allied war efforts were first and foremost aimed at a speedy capture of Nazi-Germany. They left the Netherlands by the way side, literally.

Details of German atrocities like the large scale razzias and destruction, leaked out and Gerbrandy used them in his press offensive. This did have effect in the sense that the fate of the Dutch population became known to a massive audience. On December 16, 1944, he wrote a letter to the allied Supreme Commander, General Dwight Eisenhower: 'Hulp aan bezet Nederland ten tijde van de bevrijding moet boven alles prioriteit krijgen. … De Nederlandse regering kan de bevrijding van lijken niet toestaan.' (Aiding the Netherlands at the time of the liberation must be given priority above all else. ……The Dutch government can't allow the liberation of corpses.') The New York Times published an article on its frontpage, indicating among other things: 'Not a single nation will have to claim so much from the Germans as the Netherlands.'[8]

Definitielijst

- interbellum

- “Latin: Between war”. Years between the Great War and World War 2.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- offensive

- Attack on a smaller or larger scale.

- railway strike

- This was announced on the radio and complied with by the Dutch railway staff on 17 September 1944. The railway strike was intended to support the allied plan Operation Market Garden. After the allied airborne landings had failed, Dutch railway staff remained on strike until the liberation.

- Reichskommissar

- Title of amongst others Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the highest representative of the German authority during the occupation of The Netherlands.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Origin of the famine

Transport crisis

The Germans soon realized that a shortage of all basic needs would lead to chaos (spreading of) diseases and possible revolt in the western provinces. Certainly now when battle was raging in the south of the Netherlands, the military could do without this. Wehrmachtsbefehlshaber and General der Flieger Friedrich Christiansen therefore advocated the ending of the embargo on transport. After some urging, Seyss-Inquart consented. On October 16, 1944 he lifted the ban on transport of potatoes. On November 8, transport of other food stuffs was allowed again. This didn't solve the transport problems though. The Wehrmacht refused to provide ship space for the transport of food.

Black trade also increased sharply. Whereas initially 20 to 25% of the production disappeared into the illegal circuit, after October 1944 this rose to over 40%. Illegal agricultural production rose to 43% in 1944 and remained at that level until 1945.[9] This was partly caused by farmers and traders fearing confiscation by the Germans but greed certainly played a role as well. The black trade triggered severe problems for the centrally led food distribution. In addition, the authority of public officials was being undermined by calls from London and the resistance to refuse all cooperation with the occupation authorities, even though it was within the framework of the food distribution.

A characteristic element of a famine is that there is always more than one cause. The same applies to the Hongerwinter. It can't be stated this came into being only because of the call for a railway strike or the ban the Germans had imposed on transport. These factors did contribute to the famine but there were more causes such as the general limitations inherent to war and occupation. Think for instance of the shortages of fuel mentioned before, problems with transport, inundations and large scale German razzias.

The Hongerwinter wasn't just a food crisis but more like a transport crisis. The main problem was to get the scarce food into the cities. Initially, this was hampered by the railway strike and the German ban on transport but later on also because part of the food ended up on the black market and transporters faced problems because of the fuel shortage, confiscation by the Germans and fire from the Allies.

Transport being the main problem also becomes clear from the fact that during the last year of the war, the food situation in the northern and eastern part of the country remained at an acceptable level. Partly because of the agriculture in the area, the bread ration in for instance Friesland stood at 49 ounces per person per week whereas in Amsterdam, this stood at only 18 ounces.

By the way, the food situation in the liberated south wasn't favorable either. Right after liberation, the food ration stood at 1,250 kcal and in some parts of Brabant, this dropped to 800. Due to the heavy fighting in this area, the infrastructure had been damaged, making delivery difficult. The shortage of food, clothing and fuel triggered protests in for instance Eindhoven. Even hunger trips were made in Brabant. Towards the end of November 1944, the situation improved as the Allies allowed more food to be delivered to Antwerp. As during these months, the front in the south stabilized, more means of transport became available for the delivery of food to the civilian population. This ended the famine in the south. In the occupied part of the Netherlands the situation gradually deteriorated.

Start of the famine

Autumn was cold and wet. In November, it rained heavily. This rain and the lack of workers thwarted the harvest of potatoes and beets. Agricultural production decreased as a result. Contrary to previous years, in the spring of 1944 there was no reserve available. Early October 1944, the supply of electricity for personal use was cut off in the western provinces due to a shortage of coal. In November, delivery of gas to private persons was cut off as well. Only factories and German institutions were being supplied. Before that by the way, gas and electricity were only available to Dutch households for a few hours per day but now, lighting and heating was made very difficult. The mood in the country was described as apathetic.

As from November the official daily rations in the western provinces had dropped to below 750 kcal per day. In comparison, the human body needs at least 1,200 kcal per day to take in the necessay nutriments, 1,200 kcal being the absolute minimum. On average, a female needs 2,000 and a male 2,500 kcal per day.

At the end of November 1944, an anonymous author from Rotterdam wrote: 'Het leven in bezet gebied is als het leven in een gevangenis. Ieder ogenblik kunnen de bewakers de cel binnenkomen: Licht is er niet, verwarming evenmin en eens per dag krijgen we een ontoereikende kliek eten.' (Life in the occupied area is like living in prison. Guards can enter the cell at any moment: there is no light, no heating as well and once a day we get an insufficient amount of food.')[10] At that moment, the daily ration in Rotterdam consisted of 7 ounces of bread, 11 ounces of potatoes, 0,3 ounces of fat and butter, 0,9 ounces of legumes and 0,2 ounces of meat or cheese. It even happened often that people didn't even get these meagre rations or not at all. Nel Bakker, at the time a young woman in Amsterdam who claimed not to belong to a 'privileged group', declared later: 'In die tijd moest je in de winkel lang wachten op je rantsoen. Eens per week een half brood, dat scheen te bestaan uit een mengsel van stopverf en zaagsel, waar we toch nog happig op waren.' (In those times you had to wait a long time in the shop for your ration. Once a week half a loaf of bread that seemed to consist of a mixture of putty and sawdust but we were happy with it nonetheless.') After the First World War the Netherlands had sent food to the starving population in Germany and Austria. Soon, the mocking joke circulated that the Germans were so thankful to the Netherlands that: 'now they give every Dutch child one potato and two slices of bread per day'.

In a message to London from a Dutch resistance group on November 24 it was indicated there was a famine in the cities. Especially in The Hague, the situation was alarming. The city had no hinterland like Amsterdam and Rotterdam where people could get additional food from. The Hague was therefore the first city where hunger riots erupted. The Germans shot some pillagers.

Definitielijst

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- railway strike

- This was announced on the radio and complied with by the Dutch railway staff on 17 September 1944. The railway strike was intended to support the allied plan Operation Market Garden. After the allied airborne landings had failed, Dutch railway staff remained on strike until the liberation.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Food sources

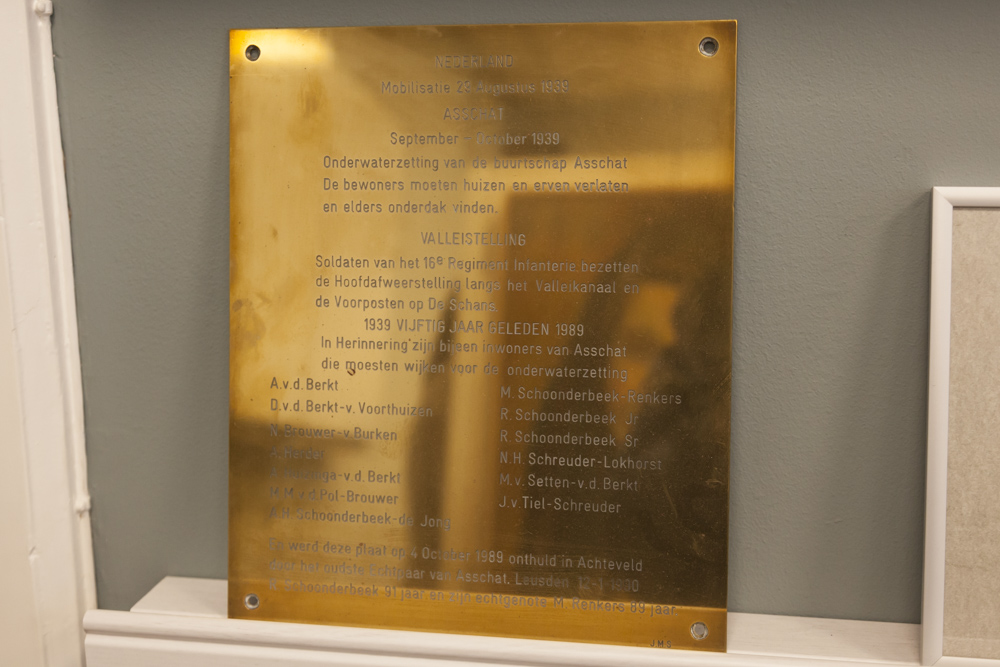

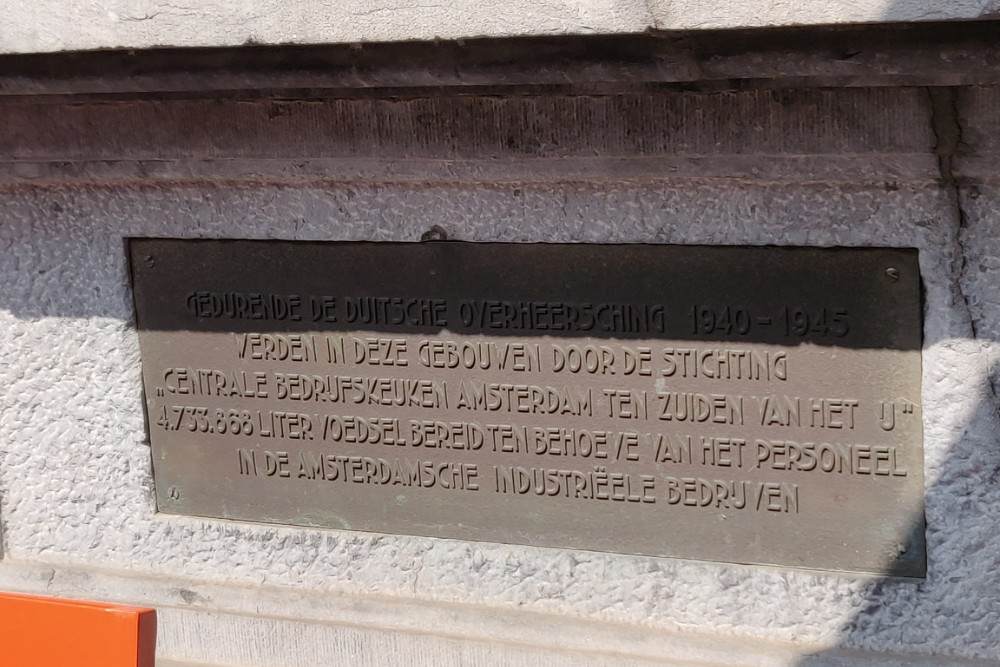

Soup kitchens

As early as 1940, so-called Central Kitchens were established in the country which gave food to people, against payment and a voucher, to those who unable to prepare it at home. They also supplied additional food to specific groups which were entitled to supplementary nutrients such as children and workers in specific sectors. Up until 1944, few people would call upon this institution because for instance the NVD was involved. (The NVD was a Nazi institution which aimed at social support). This changed after 1944 though. Also because many members of the NVD had fled on Crazy Tuesday, the RBVVO could regain control over the Central Kitchens.

After gas and electricity had been cut off, the kitchens started to provide meals on a large scale. In The Hague, the number of meals supplied rose from 3,700 in September to 209,400 in December 1944 at the cost of 20 cents and a potato voucher. People received 0,1 US pints of warm meal, usually stew or soup. Soon however, the ration dropped to 1,6 pints. During the winter, a portion usually was only 1 pint. Initially, the quality of the food was good but it decreased during the winter. Some claimed the food from these kitchens was so bad, even domestic animals wouldn't eat it. The population called the ration 'cementsoep' or dirty dishwater. Bakker declared she always gave her portion away, except when it consisted of grits, 'because I couldn't stand the other mixtures. Rather than that I remained hungry,'

All of this doesn't leave untold that during the Hongerwinter many people relied on this institution in order to survive. In April 1945 in Amsterdam alone, over 400,000 inhabitants would fetch a meal from these soup kitchens every day. During that month, a total of 1,8 million meals would be prepared daily. In Leiden, 71,9% of the urban population called on this institution.

Central shipping company

Throughout November 1944, Louwes and Hirschfeld attempted to get the delivery of food off the ground. To this end, the Centrale Rederij voor de Voedselvoorziening or central shipping company for the supply of food was established on December 5, a coordinating body for inland shipping. This was a success. The amount of food, delivered via the IJsselmeer tripled during that month. All told, the company would ship 170,000 ton of food to the west of the country. The transporters though, despite German promises, kept suffering from confiscations. Strafing by Allied aircraft also posed problems. A still greater obstacle was that once the transport got off the ground, canals, rivers and the IJsselmeer froze over. Partly due to a shortage of vessels, most shipping lanes couldn't be kept open.

On January 12, 1945, the Centrale Rederij reported: 'De achterstand sinds september 1944, veroorzaakt door embargo, inbeslagname van groote voorraden graan, het verlies van drie provincies die overschotprovincies waren, en de belemmeringen bij het dorschen ondervonden, is niet meer in te halen, zeker niet, nu ook de vorst is ingetreden.' (The backlog since September 1944, created by embargo, confiscation of large amounts of grain, the loss of three provinces that used to have a surplus and the limitations in threshing, can't be cleared any longer, certainly not now frost has set in.')[11] This was true. In January, the rations dropped to 500 kcal a day. Mortality increased. After the period of frost, transport was resumed but this was thwarted by the lack of vessels and the growing shortage of fuel. Transport of food decreased until mid-April when shipping stopped altogether.

Hunger treks

In November 1944, people from the west trekked to the countryside in their masses in search of food. They first called on the farmers in the western provinces Later on, they also went to the agricultural areas in the north and east of the country. These hunger treks are often labeled as one of the sad low points in this period. The image of numerous malnourished and poorly dressed people trekking to the countryside on shaky bikes or on foot in all kinds of weather is one of the most common associations with the Hongerwinter. Early 1945, Hirschfeld wrote in his diary: 'Op den terugweg van Apeldoorn zien wij ’s avonds de ellende van de langs de wegen trekkende bevolking, die op foerageren uit was. Een duidelijker beeld van den heerschenden hongersnood heb ik zelden gezien.' (Returning from Apeldoorn in the evening, we observe the misery of the people trekking along the road who are foraging. I have never seen a clearer picture of the prevailing famine than this.'[12]

Later on, journalist J.G. Raatgever wrote about the hunger trekkers: 'Ik heb ze zien zwoegen voor hun karren of achter het stuur van hun bakfiets, door een decimeters dikke laag sneeuw, pal tegen de gierende oostenwind op, maar ik zag ze ook liggen, langs de weg, in elkaar gezakt van vermoeidheid, bevangen van de koude, vaak stervend van ontbering.' (I watched them toiling pulling their carts or at the handle bar of their cargo bike, through feet of snow, straight into the howling eastern wind but I also saw them lying on the side of the road, collapsed from exhaustion, overcome by cold, often dying from privation.'[13] Indeed, horrendous scenes also took place. G.J. Kruijer, who conducted extensive research into the hunger treks, recorded a statement by an inhabitant of Amsterdam on a hunger trip who encountered a boy with a hand cart with his deceased younger brother on it.

It wasn't only doom and gloom though. Roelf Tillart, 15 years of age, made a hunger trip to Groningen with his sister and three friends. In the Historisch Nieuwsblad he declared about this: 'Hoe we de weg vonden? Dat was geen enkel probleem. Er was één grote weg, en die was hartstikke vol. In lange rijen liepen de mensen achter elkaar aan, met handkarren en bakfietsen. We hoefden alleen maar aan te sluiten en mee te lopen. Wat een armoe zagen we om ons heen! Mensen met kapotgelopen schoenen, of zelfs zonder schoenen, karren met bijna afgebroken wielen, mensen die van vermoeidheid niet meer verder konden… Dat was echt niet leuk. Toch liepen we echt niet de hele weg te janken. Voor ons was het, ondanks de kou en de ellende, toch vooral een spannend avontuur. Wij waren jong en we hadden er echt zin in; een van ons had zelfs een mondharmonica bij zich.'(How we found our way? No problem at all. There was one big road and it was overcrowded. People walked behind each other in long ques with hand carts and cargo bikes. We only had to join them and walk along. What misery we saw all around us! People with battered shoes or no shoes at all, carts with wheels almost broken off, people so exhausted they could no longer go on. That wasn't funny. Yet we weren't crying all the time. For us it was above all, despite the cold and the misery, an exciting adventure. We were young and we really felt like it; one of us had even taken a mouth organ along.')[14]

In various locations, the Red Cross or private individuals had established aid stations for hunger trekkers where they could get soup and if necessary spend the night. In Harderwijk there was a Red Cross post in the Fino factory where thousands of gallons of soup were distributed among the passing trekkers.[15]

Apart from the hunger treks having to be made in harsh circumstances, participants risked losing their lives during air attacks. Groups of hunger trekkers were regularly being subjected to fire from Allied fighter pilots who assumed German troop movements were concerned. Tillart told about a strafing by British Spitfires near Staphorst: 'Eerst vonden we dat wel interessant – we doken weg in de berm. Maar toen we langs een in brand geschoten auto kwamen en mensen vertelden dat er doden waren gevallen, werden we toch wel een beetje bang. Ik heb me altijd afgevraagd hoe die Engelsen dat hebben kunnen doen.' ('Initially we found it interesting, we took cover at the roadside. But when we passed a car which had been set on fire and we were told people had been killed we became a bit frightened. I have always wondered how those British could have done it.

Not all trips were made on foot. During the Hongerwinter, the night ferry to Lemmer was common knowledge. The trip to Friesland in search of food or the evacuation of a child was in any case far more comfortable by boat than by bike or on foot. The vessels were so over booked though, it sometimes took weeks before somebody was eligible for a ticket. Moreover, this connection also had to deal with the severe frost and it wasn't always safe. In the night of January 8, 1945 two Lemmer boats collided claiming 13 dead.

The hunger treks were sharply curtailed when from March 1, 1945 on, only military of the Wehrmacht were allowed to cross the IJssel bridges. This caused many hunger trekkers to bog down. The decision was taken by the occupation authorities in order to protect the food stores in the northwest which were being delivered again by ship from February onwards. Within the western provinces, the trips were still tolerated.

During and after the Hongerwinter, many stories circulated about food being seized from hunger trekkers by German and Dutch authorities. According to official instructions, confiscation was permitted only when large quantities of food were involved and then only to fight black trade. Unauthorized seizures carried huge penalties. During surveys made after the war, participants indicated that the Wehrmacht usually left the hunger trekkers alone. Eighteen percent of them declared they had had to contend with confiscation by the Landwacht or other police services, twelve percent indicated to have been robbed by fellow trekkers.

Much has been written about the attitude of farmers during the Hongerwinter. There are numerous examples of farmers selling their products at regular prices, much lower than those on the black market or even giving food free of charge. Diametrically opposite to this are the storied about farmers who were not exactly hospitable or even hostile. There are sporadic examples of how far some farmers would go. A woman declared after the war that a 60-year-old male wanted to have sex with her in exchange of potatoes. She continues: 'Kijk, ik zou het gedaan hebben. Dat meen ik. Maar de angst dat ik zwanger zou raken was te groot. Dus toen heb ik het niet gedaan. Maar anders… ik had het gedaan. Want je was zover, dat je alles deed om maar te eten.' ('See here, I would have done it. I mean it. But I was too afraid of getting pregnant. So, I didn't do it. But otherwise …. I would have done it. You were already so far down, you would do anything for a meal.')[16]

The hunger trekkers complained about being treated as beggars. It should be said here that some of them really were. In turn, the farmers talked about the 'boorish and unreliable' citizens who never had much respect for them anyway. The trekkers would seldom show their gratitude for the food and shelter they received. Because people kept coming, the farmers also depleted their food stores and lost their patience. On an average day, some 250 people came at the door of some farms, asking for food and/or shelter. Hunger trekkers sometimes stole potatoes and cattle. During the winter, farmers were less generous because rumors went around that much of the products they gave ended up on the black market. According to journalist Henri van der Zee this wasn't entirely beside the truth.

The Wieringermeerpolder, the 'grain store of the Netherlands' had a bad reputation as farmers charged exorbitant prices for their products. Reportedly, they often took gold or jewelry only. The farmers in Friesland on the other hand were known for their extreme hospitability and generosity. They would have charged normal prices for their products. The fact that Frisian farmers, in comparison to the Wieringers got far less callers at their doors because of the distance, played a role as well. One should be careful when judging or praising an entire region. Van der Zee notices: 'In die gespannen situatie kon een kleine daad veel betekenen. De weigering van een glas water leidde soms tot de veroordeling van een heel dorp. Een snee brood voor iemand die de uitputting nabij was, maakte een boerin tot een engel.' (In that stressful situation, a small gesture could mean a lot. Refusal of a glass of water sometimes led to the sentencing of an entire village. A slice of bread for someone near complete exhaustion made an angel out of a farmer's wife.)[17]. It should be noted however that people recall negative experiences more easily than positive ones.

Historian Loe de Jong wrote: 'Wanneer men er van uitgaat dat in Noord-Holland, door drie op de vier boeren, voor zover dezen hulp verleenden aan hongertrekkers gratis logies werd verstrekt en gedeeltelijk ook gratis te eten werd gegeven; dat dag-in, dag-uit in het bezette gebied als geheel meer dan vijftigduizend hongertrekkers op pad waren en dat dezen, na hulp ontvangen te hebben, er vele malen opnieuw op uit zijn getrokken, dan zijn wij van mening dat het ongunstige oordeel over de boeren dat in de hongerwinter door velen werd geveld, als onvoldoend gefundeerd moet worden afgewezen. Het zijn de misdragingen van een minderheid geweest die aan de naam van deze bevolkingsgroep schade hebben toegebracht.' (Assuming that in Noord-Holland three out of four farmers, in so far as they gave aid to trekkers, free lodging and partly free food; that day in and day out in the occupied area over 50,000 hunger trekkers were on the road and, after having received help, went out again many times, we are of the opinion that the unfavorable opinion of farmers, voiced by many during the Hongerwinter must be rejected as being insufficiently founded. It has been the misbehavior of a minority which has damaged the reputation of this part of the population.)[18]

In her book De Hongerwinter, De Zwarte indicates that of the households in the west over half made one or more hunger treks. The food that these trips yielded made an important contribution to the survival of the families. Such treks generally yielded more food than their meagre rations from the government. They often took days. During this period, participants remained in the countryside and could call on the locals for a good meal. This was an important added value to the hunger treks as well. De Zwarte concludes correctly that these trips were essential for the survival of workers families in particular.

An investigation conducted after the war in Amsterdam indicated that 60% of the families had made hunger treks and that one trek yielded 93 lbs. on average. In Geschiedenis Magazine, De Zwarte noticed (in line with De Jong) about the hunger treks and the attitude of the farmers: 'Natuurlijk bestond er winstbejag en harteloosheid onder de boeren, maar het staat vast dat de hongertochten enkel zo succesvol waren omdat talloze andere boeren wel hun hongerlijdende landgenoten hielpen met voedsel en onderdak.'(Of course, profiteering and callousness existed among farmers but the fact is that hunger treks could only succeed so well because countless other farmers did help their starving compatriots with food and shelter.)[19] Many farmers also donated food to relief actions. Many of them also provided shelter to those in hiding and many to the 40,000 undernourished children from the cities.

Definitielijst

- Landwacht

- Armed NSB-members with police authority.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Daily life

Wood chopping

The fall was cold and bleak and in January 1945 it would get colder still. On December 23, a period of frost set in which lasted until January 31, 1945. The average temperature that month stood at -1.5 to - 1.60 C. By the way, the winter of 1944-45 wasn't extremely cold for the time, contrary to what is often claimed. In the winters of 1940-1941 and 1941-1942 the average temperature was considerably lower than in January 1945. During those winters, the lack of fuel wasn't so severe as during the Hongerwinter.

In order to be able to cook and have some warmth in the house, people tried to get fuel in any possible way. In some streets, all trees and other wood like guardrails on bridges and benches, disappeared over night. As a precautionary measure, other benches were removed from parks and schools. The Germans tried to put a stop to the thievery of wood. They confiscated loads of wood, saws and axes and imposed severe penalties, all of it in vain. On November 14, the Vondelpark in Amsterdam had to be closed because of the massive felling of trees. This didn't protect it from citizens looking for combustible material. In Amsterdam, 14 parks with a surface area of 0.3 square miles were stripped of all trees and brushes. In other cities, similar things occurred. Utrecht citizen Bertus Koot wrote in his diary on January 16, 1945: 'Wegens brandstofgebrek worden alom in en om Utrecht bomen omgezaagd, zowel dik als dun. Ondanks het verbod van de Duitsers gaat dit voort. Nu moeten alle mannen, waarschijnlijk boven de 18, wacht lopen in de plantsoenen.' ((Due to a lack of fuel, everywhere in and around Utrecht, trees are being cut down, thick ones as well as thin. This continues despite prohibition by the Germans. Now all men, probably above 18 have to stand guard in the parks.')[20] In Utrecht, some 5,000 trees would be cut down. In Leiden, out of the pre-war 5,330 trees. 390 were still standing after the liberation. Relatively speaking, most trees were chopped down in Hilversum, 13,000 which amounts to 165.3 per 1,000 inhabitants.)

Not only trees fell victim. In the Jewish quarter in Amsterdam, 750 houses were robbed clean of all wood, furniture, staircases, floors, etc. This happened in abandoned houses as well. Houses sometimes collapsed in which people were busily removing - in unprofessional manner - stairs and floors for instance. Such cases claimed a total of five dead and dozens injured. During the hunt for wood in Amsterdam, 1,500 houses would be demolished; 1,800 in The Hague. All blocks of wood between the rails of the trams were removed. Normally these served to prevent vibration from passing trams. As they were impregnated, they burned well. Removal of these blocks caused numerous accidents and huge traffic jams. In Rotterdam, girders in underground shelters were removed and even cinders from beneath the town squares. When in March 1945 all stocks were depleted, people started to remove and burn the wooden interior of their own homes.

The wood and anything else which was even half way combustible was burned in home-made stoves, usually made of an iron bin with a grid on top, set into a larger bin. Such majo stoves were insufficient to heat the house but yielded just enough heat to cook. They could only be fed by raw wood shavings, paper and other highly flammable material. A housewife in Amsterdam lamented that such a stove demanded more attention than a baby because: 'sometimes you could leave a baby alone for 10 minutes or so'.[21]

Despite the dire situation, the Dutch population attempted to make something out of Christmas anyway. For fir branches, usually disposed of as garbage, HFL 4 was charged. A diary writer commented: 'Dit is de vreselijkste kerst die we ooit hebben beleefd. Er is niets in huis, niets om te eten en natuurlijk ook geen boom en geen enkel kaarsje.' (This is the worst Christmas we ever had. There is nothing in the house, nothing to eat and of course no tree and not a single candle.')[22] The few restaurants that were still open asked the guests to take their own cutlery. In an apartment in Amsterdam, the Crone family spent the Christmas holiday largely in bed as that was the only place in the house where it was warm. There was hardly any food and Christmas dinner consisted of nothing else than winter carrots.[23] It was not bad for everyone. During Christmas celebration in Clingendael, the residence of Seyss-Inquart, three sorts of meat and two flavors of ice cream were on the menu.

About New Year's Eve, it was noted that it was notably quiet in the streets. Even the Germans stayed inside. A diary writer from Rotterdam remarked: 'Zij hebben drank, sigaretten en meisjes die hun eer verkopen voor een nacht van licht en warmte.' (They have booze, cigarettes and girls selling their honor for a night of light and warmth.' Nel Bakker cynically wrote in her diary: 'In plaats van kerstverlichting en vuurwerk hadden wij het geratel en de zoeklichten van afweergeschut.'('Instead of Christmas lights and fireworks, we have the racket and searchlights of anti-aircraft guns.') Sadly enough, after Christmas, the worst of the Hongerwinter was still to come.

Black market prices rose. At the time a Dutch worker earned on average HFL 2,000 a year. The price of a bag of wheat rose to HFL 4,000. On the black market during the Hongerwinter, a loaf of bread of 1.8lbs. was priced at an average of HFL 40 up to 80 or more: this while the official price was less than 1. People bought butter for HFL 75 per pound, milk was HFL 5 a pint and one egg HFL 7.[24] In fact there was no such thing as a uniform black market. Prices varied strongly, depending on the location where the products were on sale and also on the relation between buyer and seller. In the cities, the prices were twice as high as in the countryside. Barter trade increased. A Jewish couple, in hiding in Amsterdam declared after the war that in January 1945 they had sold their jewelry in exchange for one loaf of bread. 'De kosten waren enorm. We zijn financieel geruïneerd, maar… we hebben het overleefd.'(The cost was enormous. We have been ruined financially but …. we survived.')[25]

The bad situation of the food also had its effect on general health. During a famine, all diseases increase except cancer. The mortality among people suffering from hunger oedema, diphteria or typhoid rose dramatically. Due to the lack of warm water, persons had to contend with skin diseases more often. Diptheria increased from 1.25 to 66 cases per 10,000, typhoid from 2 to 225 per 100.000. The number of people suffering from disorders caused by lack of vitamins like scurvy wasn't alarming. This because vegetables were readily available during the entire winter. On the other hand, there was a huge shortage of medicine such as insulin. Thanks to crossings of the Biesbosch to the liberated south and the International Red Cross, some supplies could be delivered but it was far from sufficient. All this attributed to an increase of diseases and mortality.

A man in The Hague during the hongerwinter. His legs show marks of oedema. Source: Beeldbank WO2 / Collectie Huizinga

The limited rations of fuel and food in the west naturally caused the greatest problems. There was also a shortage of soap. Each household was entitled to one bar of soap measuring 0.8 to 2" a month. The surrogate product didn't clean or produce foam though. Some tinkered at home with a better equivalent. Egbert van der Haar from Glanerbrug recalls: 'Vader was heel handig. Hij had op de een of andere manier zeep gemaakt. Tjalkvet (talg) met water en kaliumloog en haliumloog of zoiets. Om er wat stevigheid in te krijgen kwam er wat klei uit de beek bij in. In een groot raamwerk met vierkante vakjes werd de zeep bij ons thuis op de overloop te drogen gelegd. Maar oh, wat kraste die zeep. Maar we werden er wel schoon van. Het hielp goed tegen de vlooien en luizen. Daar kon geen luizenkam tegen op.' (Father was very handy. One way or another, he had made soap. Tallow and caustic potash and caustic soda or something. In order to get some firmness into it, some clay from the brook was added. This soap was laid out to dry on the landing at home in some sort of frame with square sections. Boy oh boy, that soap scratched. But it did clean us. It was good against flees and lice. Not a single lice comb could match it.')[26]

Hirschfeld described January 28, 1945 in his diary as the lowest point. The bread ration was reduced from 35 ounces to 18 per week. As a result, the daily ration stood at 460 kcal which would decrease further to 340. Cabaret artist Paul van Vliet described how he, as a 9-year-old boy asked his mother whether she really had nothing to eat during the Hongerwinter. 'Zelfs geen kaaskorst? (not even a cheese crust?)' His mother indicated she really had nothing at all. 'Dat was de eerste keer dat ik mijn moeder zag huilen.' (That was the first time I saw my mother cry,')[27]

Alternative food sources

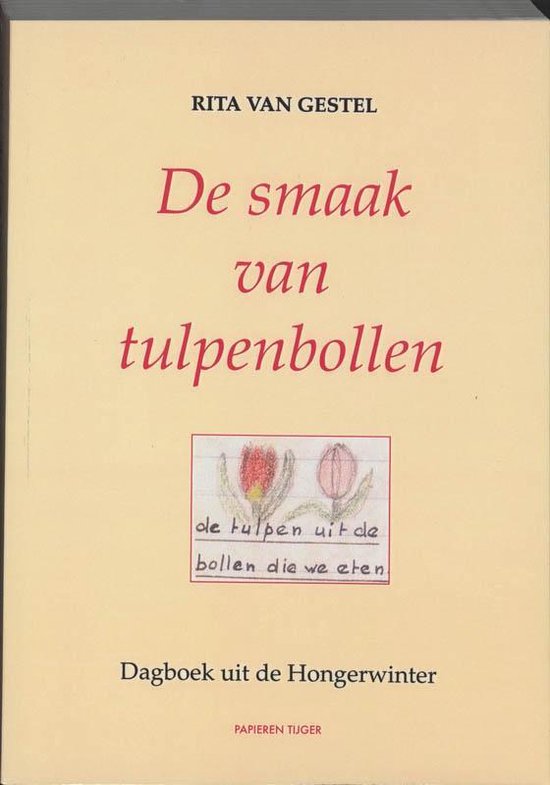

When potatoes ran out, the Dutch went searching for other food sources. Flower bulbs were an option. There were large stocks of flower bulbs that couldn't be traded anymore due to the war. Initially, the authorities warned against eating bulbs because some of them are poisonous including daffodils. On January 30, 1945, tulip bulbs also appeared on the menu of the soup kitchens. They were promoted by the food council as they contained more calories than potatoes. Recipes were distributed. The taste of tulip bulbs was described as cloying sweet and sour. On the other hand, soup made from them tasted well. The price rose to HFL 30 per lbs. A total of 140 million bulbs would be consumed. In Amsterdam, the price of one pound of tulip bulbs for consumption stood at HFL 18 in February 1945. A striking example of how the situation in the western cities differed from that in the other provinces: at the same time, tulips were still being sold for decoration in Groningen.

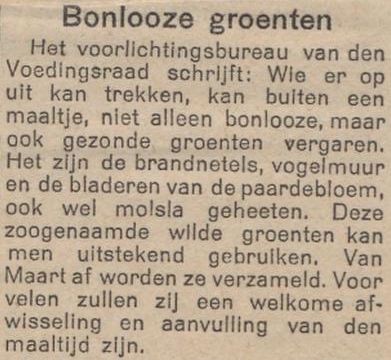

On January 15, 1945, an official announcement was made to the effect that from then on each inhabitant of Amsterdam was eligible to six pounds of sugar beets each week instead of potatoes. Recipes were distributed how to prepare them best. This was far from easy. Cooking took a few hours.Then the beets had to be peeled. For instance, syrup and pulp could be made of them. The beets were so dirty, some witnesses declared it took days before your hands were clean again. Van der Zee described the taste as disgustingly bland and sweet. Although he was almost starved to death, he ate them with disgust. All these stop gap measures couldn't prevent the caloric value of the rations from the soup kitchens from decreasing sharply: from 483 to 268 kcal. In March 1945, the food council published a message promoting stinging nettles, dandelions and bird's foot as food.

Even pets weren't safe anymore. In Wassenaar, two men were arrested for the illegal slaughter of dogs. They sold the meat at HFL 40 a pound. Wim Dome from Rotterdam described in the NRC how his father, during a visit to a family, stole his brother's cat in an unguarded moment and slaughtered it. There were stories about people baking and eating their own gold fish and of someone who caught gulls and ate them.

Many people became very inventive in achieving food. It blurred the border between right and wrong. This is a typical characteristic during a famine. The number of thieveries and plunder increased sharply, despite the German authorities taking strong actions against it. In The Hague, three plunderers were summarily executed. By the way, the resistance also took strong actions against criminals. In the Zaan region, homes were broken into much more often than normal in the Hongerwinter. These raids were carried out by a number of gangs. The police couldn't take counteractions because of a lack of means and personnel. The resistance, in possession of the names of some involved, sent numerous warning letters. When despite this, the number of burglaries and raids didn't decrease, numerous perpetrators were executed.

Definitielijst

- heat

- High-explosive anti-tank warhead. Shaped charge projectile to punch through armour. Used in e.g. bazooka or in the Panzerfaust.

- International Red Cross

- Name of a complex of co-operating humanitarian organisations which primarily focusses on providing assistance to the sick and wounded military during wartime, to prisoner of war and to civilians during wartime and other conflicts. The role of the Red Cross during World War 2 is somewhat controversial.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- surrogate

- Literally meaning substitute. Due to a shortage of raw materials during World War two various surrogate products were sold. Surrogate coffee is an example of a product that was offered instead of real coffee.

Domestic aid and mortality

Relief operations

During but in particular after the war, the image arose of an apathetic population that everyone endured meekly. Hirschfeld for instance wrote in his diary on February 1945: 'De honger maakt de menschen voor een deel apathisch en verdierlijkt hen wanneer zij eens eten machtig worden.' (Hunger makes some people apathetic and turns them into animals once they obtain food.' Further on, he talked about a concentration camp mentality. This however is not the whole story.

From within society, many actions were actually taken to do something about the food situation. Many enterprises for instance established their own food committees. Representatives traveled to the northeast to gather food and fuel. They also saw to the laying out of small allotment gardens. In Delft, a cooperation between 35 enterprises was extremely successful. They opened a central factory kitchen on Lange Kleiweg where they served 5,000 meals a day to their employees at the cost of 5 cents. Private persons set up their own relief actions as well. Family physician J.H. Wagenaar established an emergency committee in the Amsterdam suburb of Betondorp. In close cooperation with the resistance and the police, food was gathered and distributed. The food mainly came from farmers in the northeast of the country. The committee managed to serve no less than 132,000 meals to children between the ages of 6 and 16 during the months prior to the liberation, which avoided famine in this suburb.

There were more of this kind of actions where locals united to do something about the food situation. Another example is Actie op de Eilanden This was one of the poorest suburbs in Amsterdam. An interchurch committee managed to provide a daily meal to 4,000 children during the Hongerwinter. The committee also took care of 500 persons in hiding and 800 elderly. Hence the image in popular media that the Hongerwinter was a period of social disintegration in which everyone fended for himself is incorrect according to historian Ingrid de Zwarte.[28]

Eventually, the churches were to play an important role in offering and coordinating relief to the starving population. This was also recognized by Louwes and Hirschfeld. The churches had frequently and openly criticized the measures of the German occupier, winning much confidence among the citizens. The religious institutions were considered non-political, causing the Germans to take a positive stand towards their role as well. Moreover, within the churches, there was a wide spread organizational structure that had largely remained intact. People also assumed that in general strictly religious farmers in the north and east would more readily cooperate with a religious organization. A Dutch secret agent reported to London in March 1945 that farmers denied requests by official government bodies to donate their milk to children in the major cities. 'Maar als een dominee of priester ze dit opdraagt, dan zijn ze onder de indruk en is hun enige vraag, hoe zit het met het transport? Antwoord: de ondergrondse beweging, die voor de valse papieren zorgt.'(But when a minister or priest orders them accordingly, they are deeply impressed and their only question is "how about transport?" Answer: "The resistance which provides the forged papers."')[29] Resistance groups were also represented in many (clerical) relief committees.

Louwes took a positive stand towards the individual relief actions that bypassed the official distribution. Partly on his initiative an overhead organization was created to coordinate those actions. To this end he looked to contact the Interkerkelijk Overleg der Protestantse Kerken (joint council of the protestant Churches) in cooperation with the Roman-Catholic Church (IKO). With permission from Seyss-Inquart, the IKO paved the way on December 11, 1944 by establishing the Interkerkelijk Bureau voor Noodvoedselvoorziening (joint office for emergency food distribution), (IKB). This institution occupied itself with providing help with food and the evacuation of children from the cities in the west to the agricultural provinces. All of this with the slogan 'by the churches, for all'. Non-religious people were eligible for help as well. Although cases are known of IKB branches not providing food to people of other religions or only benefitting people of their own belief, in general help was actually offered to everyone. Distribution of food was based on medical or social indication and not on belief or political color. The main office of the IKB was located in The Hague. Local branches were established, spread across the (still) occupied provinces. The IKB would evolve into an organization with thousands of volunteers and hundreds of distribution points. The office operated quickly, effectively and with great success. It became operational in January 1945. A female volunteer from The Hague declared after the war: 'Ik werkte toen op de uitdeelpost van het IKB aan de Fluwelen Burgwal. Daar kregen we die maaltijden; bijvoorbeeld: de ene dag porties soep en de andere dag was ’t pap. Dan kwamen om twaalf uur de volwassenen. Die waren dus gekeurd, en al naar gelang hun gewicht en lengte kregen ze toestemming om een kaart te kopen. Want die moesten wél betalen voor die maaltijden; dat was een eis in die tijd. Ze moesten evenveel betalen als bij de centrale keuken. En voor zover ze het niet zelf konden betalen werden die kaarten later betaald via de kerkgenootschappen.'(At that time I worked at the IKB distribution point on Fluwelen Burgwal We received those meals there; one day portions of soup, the other day it was porridge. The adults came at noon. They had been examined and based on their weight and height they were permitted to buy a card. They did have to pay for those meals; that was mandatory at the time. They had to pay just as much as in the central kitchen. And in so far they could not afford to buy cards, those would be paid for by the churches later on).[30]

Children who were diagnosed with underweight after medical examination were eligible for half a pint of additional food. This consisted of stew (often a mixture of potatoes, vegetables and sugar beets) or porridge.

During the Hongerwinter, children were given 1 U.S. pint of additional food a day. Distribution of food by the IKB. Source: Beeldbank WO2 / Collectie Huizinga

These relief actions added 450 to 650 cal on top of the ration of those who needed it most. The largest group was made up of school children between the ages of 6 and 15. Partly due to the efforts of the IKB, famine of this group was prevented. The average mortality among school children in the urban west was even lower than in the liberated part of the country. The IKB focused mainly on school children because children were considered as a group which needed the most support. Initially toddlers and infants received no support as they did receive supplementary rations from the government. Later on, the IKB reconsidered when it appeared that mortality among toddlers increased. The IKB was to support over half a million people.

Evacuation of children

At the end of 1944, the evacuation of weakened children (the so-called palefaces) from the starving west to foster parents in the north and east of the Netherlands got under way. Initially this was taken up by churches and enterprises. From the middle of January up to the end of March 1945, these relocations would by coordinated by the IKB. Children were examined first to determine whether they were eligible for a stay in a foster family. Children of more than 20% underweight were given priority. Before placing it in a foster family, the religion and background of a child was taken into account as well. One of the evacuees was the future cabaret artist Paul van Vliet who stayed in Friesland from January 1945 onwards.

In February 1945, the Nederlandse Volksdienst also began to evacuate children. On March 9, two vessels carrying 500 undernourished children from Amsterdam arrived on Texel. The first few days after arrival, they had to be fed cautiously and sparsely because their stomachs couldn't handle much food. Therefore, milk had to be thinned down with water.[31] The IKB would evacuate a total of 16,000 children, the NVD some 8,000. In addition, there were 'wild' evacuations when families, supported by the local church/enterprise or not, sent one or more children to the agricultural areas to regain strength.

From the end of March onwards, the increasing violence of war on Dutch territory made further evacuation too dangerous. De Zwarte calculated that a total of 40,000 children had left the starving west. Because of the war, it was difficult to arrange transport. Therefore the journey sometimes took a few days or even weeks. A real horror unfolded in Haarlem. There, a transport came under fire from a British fighter on February 21, 1945, claiming the lives of seven children, the supervisor and the driver. Having said that, evacuation of children was a great success generally. Those 40,000 children could regain their strength in the countryside, relieving other members of the family. These often had more food at their disposal because they kept the ration cards of the evacuated children.

Demises

Physicians reported a total of 8,305 official deaths from hunger; the first in November 1944 and the last in July 1945. Most deaths were in March. Mortality among men and in particular the elderly (singles) was twice as high as among women. Among men over 70, in March 1945 this was even four times higher as normal (40 per 1,000 instead of 10 per 1,000). In a home for the elderly in Amsterdam, 315 residents died. In another home there were 60 corpses in the chapel at a certain moment. Apart from homes for the elderly, in other nursing facilities the number of deaths rose sharply as well. In the psychiatric institution the Willem Arntzhoeve in Den Dolder, 477 out of a total of 1,400 patients died in the period between October 1944 and May 1945. This mortality as a result of hunger and diseases was partially caused by the institution being led by a number of fanatical members of the NSB who didn't acknowledge the use of good nursing of people who didn't contribute to society. At the lowest point, the daily ration consisted of just two slices of bread and a pint of watery soup. A physician described how those patients who were (mentally) somewhat more healthy, ransacked the kitchen garden of the facility in search for food. The others were sitting apathetically around the stove. In facilities where the staff did care for their patients, the mortality rose during the winter to 30% and even higher.

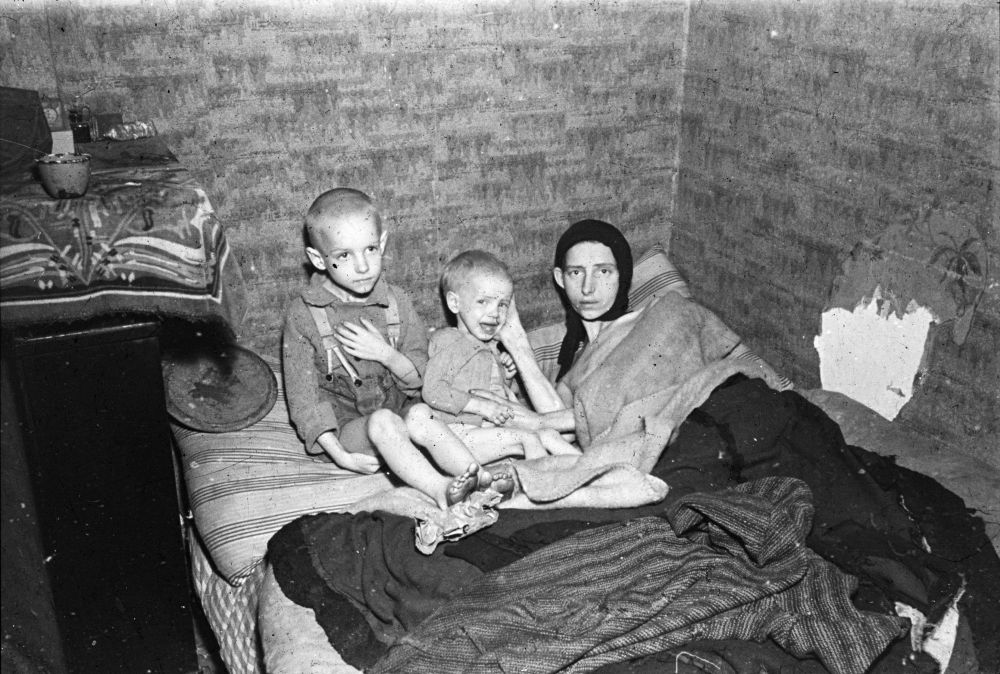

Persons with a low income and/or without a social network in particular had a hard time. These were mainly single elderly males. On December 23, 1944 P. Linschoten, an inspector of the Volkswoningen, encountered a distressing situation in a house on Houtplein in Utrecht. This was a suburb where 'asocial' people lived under supervision. The family, a woman and three children, lived in a soiled house. They were severely undernourished, were covered in lice and suffered from scabies. The father had abandoned his family and the mother was unable to care for her children. Although the family was admitted to hospital, the two youngest children wouldn't make it.

The lack of personnel, fuel and horses hampered the work of the undertakers. Moreover, there was a huge shortage of coffins. Many corpses remained above earth for weeks. On the black market, prices for transporting mortal remains to the graveyard, stood at a maximum of no less than HFL 500. In Amsterdam, the empty Zuiderkerk was converted into a mortuary where corpses, often of the poor and/or people who lived far away from a graveyard, were preserved until they could be buried. Initially, emergency coffins were used, mostly made of paperboard. When even these were no longer available, undertakers started using swap coffins that could be used for multiple burials due to the removable bottom. Yet it happened people were buried without a coffin. Some corpses were just wrapped in paper.

When public official Veldkamp, who had been named supervisor by the city council, arrived in the Zuiderkerk there were 113 corpses lying there. He would never forget the stench, he said. He had an air refreshing system installed and fences erected. Soon the rumor circulated that people with shot guns had to stand guard to chase the rats away. This however wasn't the case. During those months, there were on average 50 corpses in the church (and not thousands as rumors claimed). In the coming month, Veldkamp would arrange no less than 2,800 funerals. At the lowest point of the Hongerwinter,, in Amsterdam alone there were 150 burials a day, seven times more than the average. The Zuiderkerk was to remain in use as a mortuary until August 27, 1945.

In other cities, no mortuaries were established such as the one in the Zuiderkerk Here as well, the many deaths triggered dismal scenes. An eyewitness testified how in Rotterdam 37 corpses were lying unburied in a graveyard. 'De uitgemergelde lijken liggen naast elkaar op de grond. Vel over been. Algehele ontvlezing van dijen en kuiten. De handen krampachtig geklemd, de monden opengesperd alsof de stakkers in hun dood nog roepen om voedsel.' (The emaciated corpses are lying on the ground next to each other. Skin over bone. General defleshing of thighs and calves. Hands tightly folded, the mouth wide open as if the poor fellows are still crying for food.')[32] In Rotterdam, the city would see to the burial of about a thousand persons.

Some deaths were deliberately not reported by the family so they could continue receiving the ration cards of the deceased. A story circulated about a family that kept the corpse in the house after the mother had died. For weeks on end, the remains lay in a room where other family members ate and slept. A 15-year-old girl from The Hague described in her diary how her father went to bed exhausted in March 1945 and didn't get up anymore. His corpse remained in the house for three weeks before being taken away to be buried in a mass grave. ' Mijn moeder en ik waren er niet bij. We waren te zwak.' (my mother and I could not attend. We were too weak). Jews in hiding fared the worst. When they passed away, by necessity they would have to be buried anonymously.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- NSB

- National Socialist Movement. Dutch political party sympathising with the Nazis.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Help from abroad

The government in London

The Dutch government made all sorts of proposals to do something about the situation in the starving provinces; from delivery by ship to transport by trucks straight through the lines. Gerbrandy insisted on a discussion with Eisenhower, claiming once again that the Dutch government wouldn't permit the 'liberation of corpses.'.[33] Eisenhower wrote to a subordinate: 'I think we should see him but God knows what we can promise him.' On January 5, 1945, this meeting between the PM and Eisenhower was held in his HQ in Versailles. It resulted in, among other things, a letter being written to 21st Army Group HQ, reminding them of their duty to ship 2,000 ton of food a day to Antwerp in order to stockpile food for after the liberation. It was also decided to set up a district HQ to coordinate the relief action.

Initially, Gerbrandy was pleased with the results. This changed however when it transpired that the stored food was used by the 21st Army Group for its own troops and the Belgian population. The Dutch government lodged a complaint and insisted on a speedy liberation of the west of the Netherlands. When the commander of the army group, Field Marshall Bernhard Montgomery was informed of this complaint, he wrote to Eisenhower somewhat angrily: 'The issue is rather clear. I don't have the troops at my disposal to attack the Germans in western Holland. When the Germans withdraw from there, I have to turn eastwards to fight them. I can't go to the east fighting the Germans and simultaneously advance into western Holland with the troops I have at my disposal. I can do one of the two but not both. […] Therefore it isn't clear to me why I am the scapegoat now. Except that it is quite normal for me that I am always the one to be hit when mudslinging starts.'[34]

In February 1945, British John Clark was named head of the SHAEF mission in the Netherlands. The representative of the Allied HQ in Europe diligently started stockpiling food for after the liberation. Supply was organized from the Ave Maria abbey in Tilburg. On March 14, 1945, Churchill talked about the situation in the Netherlands in the House of Commons. He indicated however that not much more could be done for the Dutch population other than stockpiling food for after the liberation.

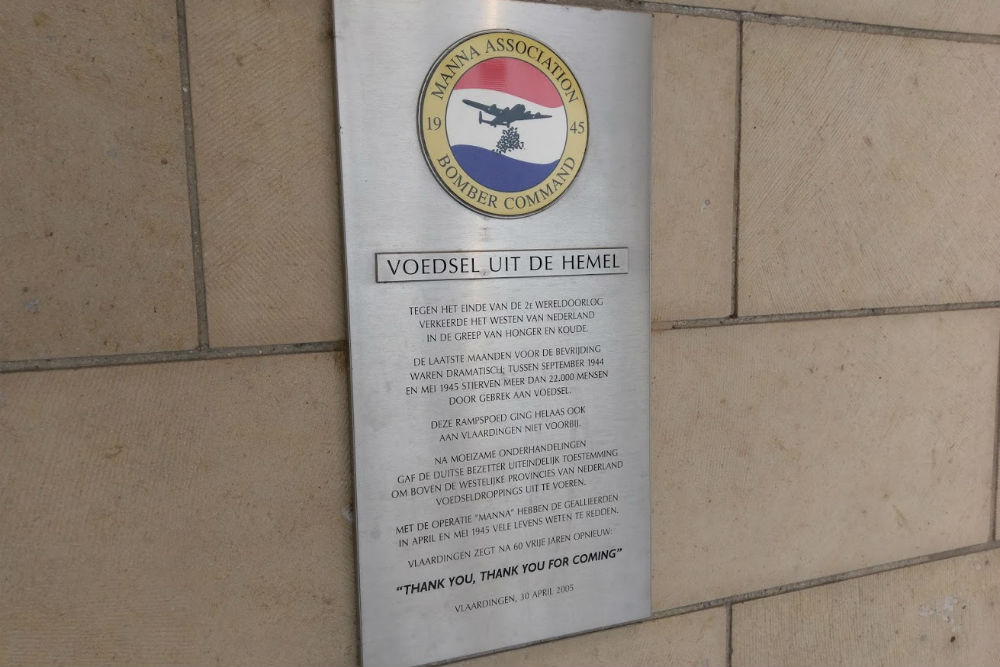

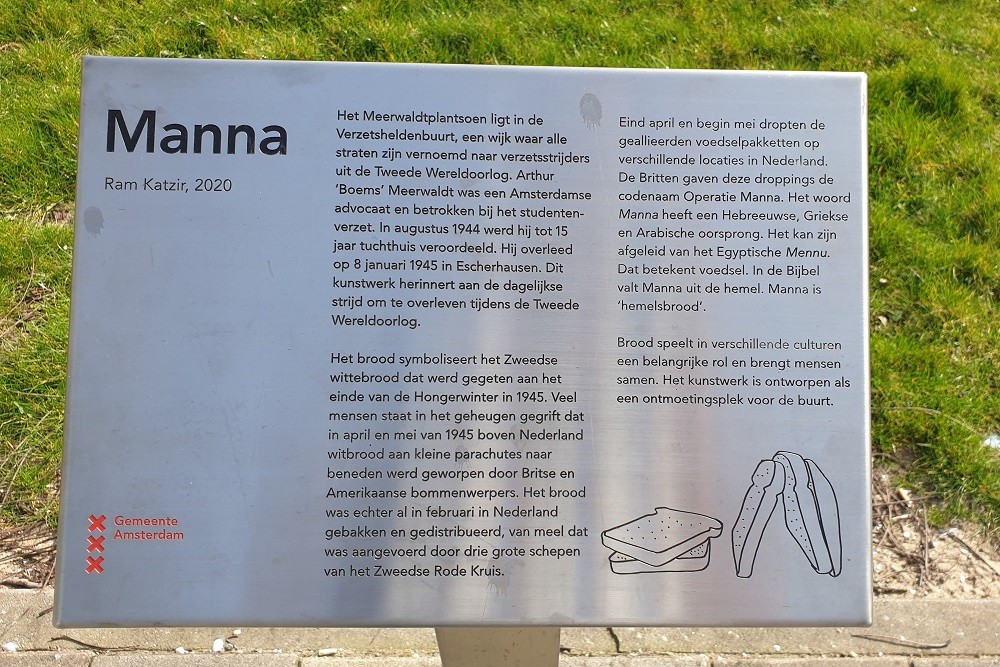

Help from outside

As early as October 1944, Sweden had offered to send food to the starving Netherlands. Thereafter, lengthy negotiations dragged on between the Germans and the Allies in which military interests had priority. The Germans refused permission to offload ships in the ports of Amsterdam and Rotterdam. By the way: the British Admiralty didn't allow unloading of ships in western ports either as this would hamper the Allied military operations too much. In the end, the vessels were permitted to berth in Delfzijl. From there, the goods were to be transported further inland by vessels of the Centrale Rederij. The Germans wouldn't allow the International Red Cross to play a role in the distribution. Subsequently, the Allies refused permission for the transport as distribution would be arranged by the Dutch Red Cross which was headed by Carel Piek, a member of the NSB. Eventually, a compromise was reached, entailing that Piek's organization wouldn't play a role and two Swedish representatives would supervise distribution. Owing to these lengthy negotiations, it took until January 1945 before the first convoy with relief goods could set sail.

On January 28, 1945, two Swedish vessels berthed in Delfzijl, carrying 3,700 ton of food including 2,000 ton of flour. Due to the frost and clerical problems it took a while before the vessel could be unloaded and distribution could start. On February 6, 1945, the day was finally there. After the war, a baker declared about it: 'Als bakker herinner ik mij als de dag van gisteren hoe we het meel aangevoerd kregen. We maakten de balen los en staken onze handen en armen tot aan de ellebogen in dat heerlijke blanke meel. Dat hadden wij in geen jaren gezien.' (Being a baker I remember like yesterday how the flour was delivered to us. We opened the bales and put our hands and arms up to our elbows into that wonderful white flour. We hadn't seen such a thing for years.)[35]

Swedish vessel Dagmar, sailing under Red Cross flag, delivers food in Delfzijl for the starving Randstad. January 28, 1945. Source: Groninger Archief

On March 6, 1945, Bertus Koot wrote in his diary: 'Het brood en de boter van het Rode Kruis ontvangen. Het was nog niet in huis of we hebben een sneetje genomen van het prima wittebrood en de heerlijke margarine. Het leek wel cake. En dan te bedenken dat het vroeger een straf was, droog brood, dat wil zeggen alleen boter erop.' (Just received bread and butter from the Red Cross. As soon as it was in the house we took a slice of that fine white bread and the delicious margarine. It tasted like cake. Come to think of it, earlier on it was a penalty, dry bread, that is to say only with butter on it.)[36]

The rations increased from 476 to 878 kcal a day. It was an improvement but of course, famine in the west of the Netherlands was far from over. Moreover, the rations soon dropped to 500 kcal. The Dutch government pleaded fiercely for periodical shipments. In the end, the British War Cabinet agreed. A total of five shipments of food from the Swedish, Swiss and International Red Cross would be sent to the Netherlands, in total 14,000 ton of nutriments, in particular grain, dried vegetables rice and milk. Consequently the rations could be upgraded with 200 to 400 kcal. This certainly contributed to fighting the famine but it still was a drop in the ocean. De Zwarte calculates that the citizens in the west, spread over 2,5 months, received less than 10 pounds of food per person.[37]

Negotiations with the Germans

In negotiations with the Germans, representatives of the Dutch government attempted to persuade the occupation authorities do something about the precarious food situation. On December 14, 1944, talks had been conducted between Hirschfeld and Seyss-Inquart. Here, Arthur Seyss-Inquart openly talked about a neutralization of western Holland. Hirschfeld noticed that the Austrian was aware of the threat of famine and wanted to prevent or at least mitigate it. More meetings would follow between German rulers, Dutch food officials and representatives of the industry. Also because the communication with London progressed tediously, no agreements could be reached for the time being. The communication was routed through the College van Vertrouwensmannen (committee of trustees). It consisted of a number of persons in occupied territory who were appointed by the Dutch government in exile in August 1944, partly to prevent a power vacuum from emerging after liberation. Gradually this committee evolved into a shadow government in which the later PM, Willem Drees, had a seat as well.

Seyss-Inquart's proposal to neutralize western Holland was discussed with the College all right but not forwarded to London. As no reaction was forthcoming, no progress was made in the negotiations. After the war, the College called the non-discussion of Seyss-Inquart's proposal a major policy error.

Hirschfeld and Louwes urged the government in London to lift the railway strike. Partly influenced by the resistance, the government declared on January 25, 1945 however, the strike should continue. This decision is subject to criticism. At that moment in the war, the strike served no purpose whatsoever anymore and only hampered the transport which benefitted the Dutch population. It must be noted here that if the strike would be lifted, it was highly unlikely whether trains could run again. Due to a lack of fuel and rolling stock, the destroyed infrastructure and Allied fighter planes which had regularly fired at trains before September 1944, this would have become a difficult operation.

On January 26, 1945, three trains with food ran to the west. These were crewed by German personnel., Seyss-Inquart announced he would permit another 10 trains carrying potatoes and four carrying grain per week, provided those would be crewed by Dutch personnel. This was passed on to London where the government indicated to consider it, provided the Allies and the College would consent. In the end, the College rejected the proposal. Early 1945, the thaw set in and ships could sail once more. There was hope, the transport of food would improve. Due to the lack of fuel, in particular coal and rolling material, delivery of food remained a problem.

Definitielijst

- International Red Cross

- Name of a complex of co-operating humanitarian organisations which primarily focusses on providing assistance to the sick and wounded military during wartime, to prisoner of war and to civilians during wartime and other conflicts. The role of the Red Cross during World War 2 is somewhat controversial.

- NSB

- National Socialist Movement. Dutch political party sympathising with the Nazis.

- railway strike

- This was announced on the radio and complied with by the Dutch railway staff on 17 September 1944. The railway strike was intended to support the allied plan Operation Market Garden. After the allied airborne landings had failed, Dutch railway staff remained on strike until the liberation.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- SHAEF

- Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, the Allied High Command in Western-Europe after the Normandy landings.

From lowest point to liberation

March 1945

In March 1945, most people would die from hunger and privation. The situation in the western provinces was extremely bad. Streets were deserted. Factories and offices had closed down. If classes continued in schools at all, this happened only once or twice a week. Many pubs were closed. The few still open were a hothouse for black trade. Nel Bakker declares that in some pubs in Amsterdam, regular guests were eligible to two glasses of jenever or gin per week. 'Die natuurlijk zo versneden was dat je er zonder merkbare gevolgen 10 had kunnen drinken.' (This of course was so thinned down, you could have drunk 10 of those without noticeable results.'

The only activity was in soup kitchens and some shops. People stood in line there for hours. The faces looked old and worn down. Due to a shortage of soap and warm water, hygiene posed a major problem. In places where many people came together, lice and scabies spread like wild fire. Garbage was no longer collected. As pumping stations that drained the waste water were out of order due to the lack of fuel, the sewers flooded. This, in combination with the massive chopping down of trees, made the cities look poor and soiled. Jan Peters wrote about the situation in Amsterdam: 'Op straat heb ik al vaak menschen in elkaar zien zakken; hetzelfde was schering en inslag in de rijen bij de Centrale Keuken tot voor kort. Op straat wemelt het van de bedelaars, meestal in den vorm van zangers en zangeressen met erbarmelijke stem. Aan de deur komen veel menschen om een snee brood of een aardappel. En daartegenover de zwarte handel in de Jordaan! Het is er in sommige straten stamp- en stampvol.' (In the streets I have often seen people collapse; the same was the order of the day at the Central Kitchen. The streets are crowded with beggars, usually in the form of singers with horrible voices. Many people calling at the door for a slice of bread or a potato. In contrast the black trade in the Jordaan! Some streets are overcrowded.')[38]

'Kinderen zwierven hele dagen over straat op zoek naar voedsel en brandstof.' (Children wandering on the streets for days, in search of food and fuel.) Wim Zaal, a 9-year-old boy at the time, declares: 'Meer dan eens zag ik een oude man of vrouw die zich op de rand van een portiek samenvouwde. Even rusten, even bijkomen, maar zij kwamen nooit meer tot bewustzijn. Ze stierven daar een ijskoude dood. Een kar kwam hen ophalen.' (More than once I saw an elderly man or woman sitting down in a porch. Get some rest, take a breather but they never regained consciousness. They died an ice cold death there. A cart picked up the corpses.'[39]