Early years

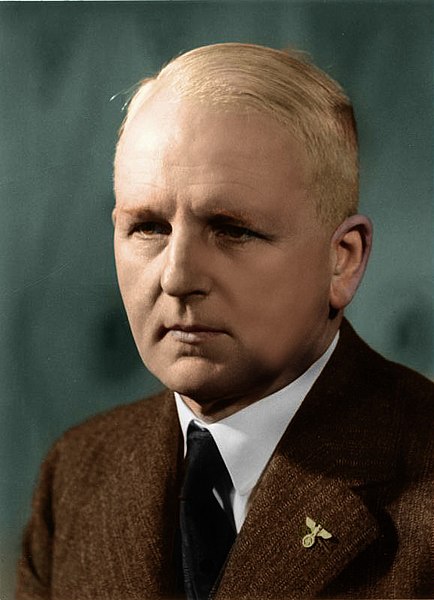

Martin Franz Julius Luther was born in Berlin on December 16, 1895. He dropped out of grammar school in August 1914. Shortly after the onset of World War I, he enlisted as a volunteer in the Prussian army. Until 1918, he served with the railroad troops. He reached the rank of reserve lieutenant.

After the war, Luther amassed wealth as an entrepreneur and settled in the Berlin-Zehlendorf villa district in the southwestern part of the capital. He had a company in removals and furniture shipping, as well as handling the furnishing and vacating of homes. In 1920 Luther married and from the marriage, three sons were born. In the years 1933 and 1934, he was the chief of a business consulting firm.

On March 1, 1932, Luther joined the NSDAP (membership number 1,010,333) and the SA. He became active outside his working hours in the SA branch of Berlin-Dahlem, a wealthy neighborhood to which Zehlendorf belonged. Luther was mainly involved in raising money for the party as the local chief of the NSV (Nationalsozialistische Volkswolhfahrt Hilfskasse), a charity organization of the NSDAP that focused on public health and welfare. In that position, he regularly visited a villa on the Lentzeallee in Dahlem to collect the necessary funds from the lady of the house. This woman was Annelies von Ribbentrop, wife of the wealthy wine merchant, Nazi confidant, and Hitler confidant Joachim von Ribbentrop. This contact was Luther's introduction to the circle of friends of the Von Ribbentrop’s, which did no harm to the until now an unknown, and somewhat shadowy entrepreneur. He was thus commissioned to redecorate the villa and expand Von Ribbentrop's private stables. When Von Ribbentrop was appointed German ambassador to Britain in June 1936, he - on the advice of his wife - he commissioned Luther to organize his move to London and to help redecorate the embassy on Carlton House Terrace in Westminster from basement to attic.

Definitielijst

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

Career in Nazi bureaucracy: Dienststelle Von Ribbentrop

The friendship with Von Ribbentrop opened the doors to the Nazi bureaucracy for the hard-working and highly ambitious Luther. In August 1936, he went to work at the so-called Dienststelle Ribbentrop, originally called Büro Ribbentrop. Founded on April 24, 1934, this bureau was headed by Joachim von Ribbentrop and was personally financed by Adolf Hitler. The working capital from the Adolf Hitler Spende (Adolf Hitler fund) amounted to RM 20,000,000. Von Ribbentrop was allowed to call himself Beauftragter der NSDAP für außenpolitische Fragen (plenipotentiary for foreign policy questions). The Dienststelle belonged to the NSDAP organization and functioned as a kind of alternative diplomatic service. It was Adolf Hitler's informal foreign policy staff that deliberately bypassed and often thwarted traditional foreign policy institutions, as well as the complex diplomatic channels of the Auswärtiges Amt (Außenministerium). Von Ribbentrop enjoyed Adolf Hitler's personal sympathy and benefitted from the Führer's distrust of traditional German professional diplomacy. Hitler considered Von Ribbentrop the ideal person to put his 'dynamic foreign policy' into practice outside the Außenministerium. The office of the Dienststelle, which eventually employed more than 300 people - called Gefolgschaftsmitgliedern - was located at 64 Wilhelmstraße, not coincidentally right across the street from the building of the ministry.

Wilhelmstraße 63/64. In the background the office of the Dienststelle Ribbentrop. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-H0115-0500-003 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Von Ribbentrop appointed party officials and personal friends, including Martin Luther, to many posts in the Dienststelle. From August 1936, Luther built up a department within the Dienststelle that was to maintain contacts with the NSDAP, the Parteiberatungsstelle (party consultancy office). He was appointed to the position of chief Referendar. After Von Ribbentrop was appointed Reichsaußenminister by Adolf Hitler on February 4, 1938, the importance of the Dienststelle in the field of foreign policy diminished. Luther initially continued to work unofficially within the Dienststelle as von Ribbentrop's private expert in matters relating to his contacts with the NSDAP. However, a transfer to the Außenministerium was not long in coming.

Definitielijst

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- NSDAP

- Nazi Party, byname of National Socialist German Workers' Party, German Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP), political party of the mass movement known as National Socialism. Under the leadership of Adolf Hitler , the party came to power in Germany in 1933 and governed by totalitarian methods until 1945.

Top of the civil service: the Außenministerium

After Von Ribbentrop's appointment as minister, about a third of the Dienststelle's staff followed their chief across Wilhelmstraße. It should come as no surprise that Von Ribbentrop also wanted to bring his confidant Luther to the ministerium. However, the transition was not without problems. Not only did the personnel department of the ministry resist this newcomer with no background in diplomacy, but a bigger obstacle presented itself within the NSDAP. In the meantime, an indictment was pending against Luther for possible embezzlement of party funds when he was active in Zehlendorf as a fundraiser. He would have to answer for this in September 1938 before a party court in Berlin, and expulsion as a party member would mean that Luther could not enter the civil service. To solve this problem quickly and effectively, Von Ribbentrop contacted Martin Bormann. The latter was at the time the chief of staff to the deputy of the Führer Rudolf Hess and in that position responsible for all important decisions in the party and state apparatus. Von Ribbentrop requested that Bormann settle the matter smoothly and in Luther's favor. Several weeks later, the party court hearing was canceled.

With this, nothing stood in the way of Luther's arrival at the ministry. Luther was initially put in charge of the newly established Sonderreferat Partei (special party department) in late 1938, which served as a liaison between the ministry and the NSDAP. In addition to his work as a liaison officer, Luther was responsible in this position for the participation of senior ministry officials and foreign dignitaries at the party conventions in Nuremberg and for foreign visits by prominent representatives of the party and state.

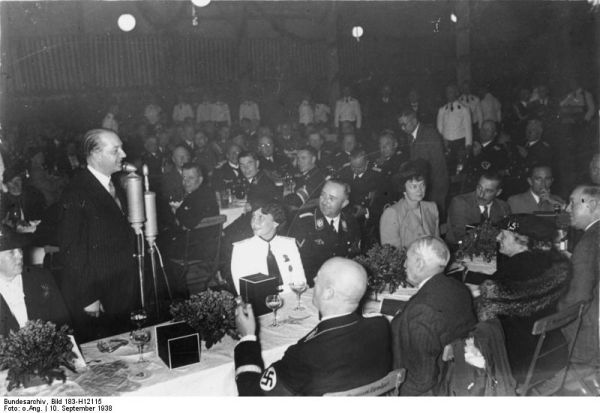

Reception of diplomats at the Reich Party Day in Nuremberg, September 10, 1938. Speaker: The Polish ambassador Josef Lipski. Seated behind the table second from left: Heinrich Himmler with Annelies von Ribbentrop next to him on the right. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-H12115 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Luther quickly moved up the career ladder. On May 7, 1940, he became chief of Abteilung D (Deutschland), which on his initiative arose from a merger of the previously existing Referat Deutschland and the Sonderreferat Partei. In this position, Luther was responsible within the ministry for propaganda and - very importantly - for maintaining contacts with all sections of the NSDAP. In particular, this involved close cooperation with the SS in the person of Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler and with the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA), the central body of the Nazi oppression apparatus headed by Reinhard Heydrich. Through his close personal relationship with Vn Ribbentrop and his network within the ministry, Luther succeeded in further expanding Abteilung D in 1940 and 1941 and making it increasingly influential within the ministry. Luther used his relationships within the NSDAP to draw especially young, highly educated, convinced National Socialists to the ministry as his close associates and department heads. They were to be trained as 'Ein neuer Diplomatentyp,' which was to curb the influence of established diplomacy.

The growing power of Abteilung D, which was increasingly occupied by 'qualified National Socialists,' was a horror in the eyes of older, traditional professional diplomats within the ministry. They saw Abteilung D, as an evil and pervasive symbol of Von Ribbentrop's foreign policy, describing it as 'a tumor in the body of German diplomacy.' It was telling that Abteilung D's office was located elsewhere in Berlin, at 11 Rauchstraße in the Tiergarten district, and not in ministry buildings on Wilhelmstraße. That physical distance was symbolic of Luther's autonomy. Contacts between the ministry and Abteilung D were mainly by telephone, and Luther barely participated in the daily meetings of senior officials at the ministry. Instructions from Von Ribbentrop went directly to Rauchstraße. From mid-1941, the activities of Abteilung D were increasingly shrouded in secrecy. Messages from the SS, Gestapo, and RSHA that were intended for the ministry were sent directly to Luther and not - as usual - through the highest official in the ministry. In this way, Luther and his closest associates determined which matters were and were not shared with other departments in the Wilhelmstrasse. The characteristic of his key position is that from 1941, Luther was the one who almost always represented the ministry in high-level official consultations between the various ministries and the RSHA.

Within Abteilung D Referat D III (subsection D III) - also called Judenreferat - was responsible for 'Judenfrage' and 'Rassenpolitik'. It was headed by the lawyer and Nazi diplomat Franz Rademacher. He was a fanatical anti-Semite, who in 1940 had drawn up the never-executed plan to deport all European Jews to Madagascar. The establishment of Referat D III did not come out of the blue. The fact that the Außenministerium was to play a role in the persecution and mass murder of European Jews, was evident as early as 1939 from a circular in the ministry entitled 'The Jewish Question as a Factor in Foreign Policy in 1938'. It read, among other things: 'The realization that Jewry in the world will always be the uncompromising opponent of the Third Reich, compels the decision to prevent any strengthening of the Jewish position.' The Jews were described as 'the disease of the people's body' and a 'radical solution of the Jewish question' was demanded. The annihilation of European Jews became part of diplomats' duties and a foreign policy goal. A German independent commission of historians concluded in 2010 that after Nazi Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Außenministerium initiated the 'solution of the Jewish question' at the European level. From the outset, the ministry actively participated in the establishment of all measures aimed at the isolation, persecution, expulsion, and extermination of European Jews.

As chief of Abteilung D - and thus also the highest chief of Referat D III - Martin Luther became jointly responsible for organizing the persecution and extermination of European Jews. Working closely with the Judenreferat (Jewry department) of the RSHA, headed by SS-Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann, Luther made Abteilung D of the ministry a government body that actively participated in the organization of the Endlösung der Judenfrage. For example, on December 4, 1941, Luther wrote in a memorandum that the occasion of the war was to be used to definitively 'solve the 'Judenfrage' in Europe'

Luther's duties included preparing and securing deportations at the diplomatic level from the countries occupied by Nazi Germany and non-occupied states allied with Germany. These include Slovakia, Romania, Serbia, Croatia, Bulgaria and Hungary. These countries, while nominally independent, were governed by ultra-nationalist and fascist governments that collaborated closely with Nazi Germany. In these countries during the war, hundreds of thousands of Jews, Roma and Sinti were persecuted, murdered, and deported to concentration and extermination camps. Referat D III chief Franz Rademacher was personally committed to this. For instance, in October 1941 he was responsible for the deportations and mass executions of Serbian Jews. He also participated in organizing the deportations of Jews from France, Belgium and the Netherlands.

Definitielijst

- Abteilung

- Usually part of a Regiment and consisting of several companies. The smallest unit that could operate independently and maintain itself. In theory an Abteilung comprised 500-1,000 men.

- Endlösung

- Euphemistic term for the final solution the Nazis had in store for the “Jewish problem”. Eventually the Endlösung would get the form of annihilating the entire Jewish people in extermination camps.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- NSDAP

- Nazi Party, byname of National Socialist German Workers' Party, German Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP), political party of the mass movement known as National Socialism. Under the leadership of Adolf Hitler , the party came to power in Germany in 1933 and governed by totalitarian methods until 1945.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- RSHA

- Reichssicherheitshauptamt. The central information and security service of the Third Reich.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- ultra

- British intelligence service during World War 2

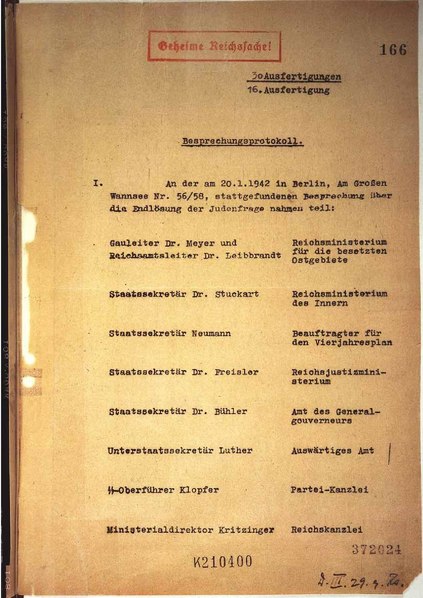

The Wannsee Conference

On January 20, 1942, a conference was held in a villa in Berlin at Am Grossen Wannsee 56/58, the purpose of which was to organize and coordinate the Endlösung der Judenfrage. Here the decision was not made on the mass murder of the European Jews – that decision had in fact already been taken with the mass murders by the Einsatzgruppen in the territories occupied by Nazi Germany in the East following the invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941 - but on the agenda was the organization and coordination of the deportation and extermination of the entire Jewish population in Europe. The German historian Peter Longerich aptly characterizes the conference - in railroad terms - as the proper setting of switches: the when, how, and where of the Final Solution was realigned between the government and party bodies involved.

The meeting had been called by SS-Obergruppenführer,Reinhard Heydrich in his position as chief of the Sicherheitspolizei (SIPO) and the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) and was attended, under his chairmanship, by fourteen senior NSDAP and SS officials, and high-ranking officials from various ministries. Martin Luther attended the conference as a representative of the Außenministerium. The year before, he had been promoted to the high official rank of Ministerialdirektor, and was now allowed to call himself Unterstaatssekretär. Luther was present as the deputy of his chief, the career diplomat Staatssekretär Ernst von Weizsäcker, the ministry's highest official and the father of later German Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker.

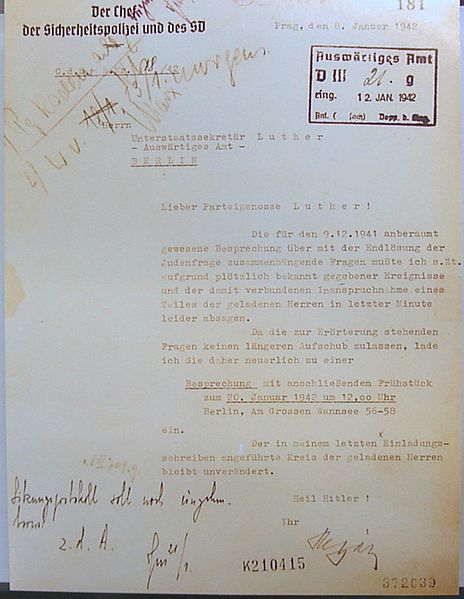

Reinhard Heydrichs invitation to Martin Luther to attend the Wannsee Conference. Source: Public Domain

In preparation for the meeting, Luther had received a written note titled Wünsche und Ideen des Auswärtigen Amtes zur vorgeschlagenen Gesamtlösung der Judenfrage in Europa (Desires and ideas of the Foreign Ministry on the proposed overall solution of the Jewish question in Europe) from his officials in Referat D III on December 8, 1941. The piece - in short - announced the ministry's approval in anticipation of the mass murder of European Jews. The desire was expressed to nach dem Osten abzuschieben (transport to the East) all Jews in the occupied territories, and in the countries allied with Germany. In addition, all European governments were to be urged to introduce Judengesetze (Jewish laws) modelled on the Nuremberg Laws.

Given this official document, Reinhard Heydrich had no trouble at all during the conference in securing Luther's - and thus the State Department's - cooperation in the Endlösung. This is clear from the minutes (the Besprechungsprotokoll, see: Wannseeprotokoll.) of the meeting. It was agreed that in implementing the Final Solution in occupied and German-influenced territories - beeinflußte Europäische Gebiete. Foreign Ministry officials would work closely with the Sicherheitspolizei and the SD.

The situation in different countries was then discussed in the villa. No difficulties were expected in Slovakia and Croatia since the 'essential core issues in this regard' had already been 'resolved.' At that time, the authoritarian and fascist governments in these countries had already started deporting Jews, Roma and Sinti to the concentration and extermination camps. Even Romania was not considered a 'problem case,' as the government there had meanwhile deployed a Judenbeauftragter (Jewish proxy). The Romanian regime would persecute and kill Jews on a large scale during the war. The minutes show that the participants in the conference were not comfortable with the situation in Hungary: it was determined that an advisor for Judenfragen should be added to the Hungarian government in the near future. Ultimately, the large-scale deportation of Jews would not begin in Hungary until after the occupation by German troops in March 1944.

In implementing the Endlösung, Luther did foresee resistance in various areas in Europe, citing the Scandinavian countries as an example. He therefore proposed suspending deportations from here for the time being to concentrate on western and southeastern Europe where he expected no difficulties. Given the small numbers of Jews in the Scandinavian countries, the suspension would not lead to a 'substantial limitation' of Endlösung, in his opinion. It was decided accorddingly.

The participants of the conference parted ways after establishing the chronological course of the following mass murders. They decided to cooperate with the Endlösung under the leadership of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt(RSHA).

Luther was anything but modest about his contribution to the conference. On August 21, 1942 he reported in a telegram to Von Ribbentrop that during the Wannsee Conference he had demanded that all questions relating to foreign affairs be coordinated in advance with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Reinhard Heydrich had promised him that and loyally kept that commitment. According to Luther, this was in line with the conduct of the RSHA department responsible for Judensachen, which had 'implemented all measures from the start in smooth cooperation with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs'.

Definitielijst

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Nuremberg Laws

- Laws promulgated by Hitler on the party convention on 15 September 1935. These laws alter alia included regulations about marriage and intercourse between Jews and non-Jews. Jews were deprived of German citizenship. Also known as the racial laws.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- RSHA

- Reichssicherheitshauptamt. The central information and security service of the Third Reich.

- SIPO

- ”Sicherheitspolizei”. Combination (since 1936) of the Gestapo and criminal police.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wannsee Conference

- Conference at the Wannsee on 20 January 1942. The Nazi’s made final agreements about the extermination of Jews in Europe, the Final Solution (Ëndlösung).

Towards the end

After the Wannsee Conference, Luther initially remained the driving force within the civil service in organizing the persecution and extermination of European Jews. Telling is a letter he sent on December 4, 1942 to Werner von Bargen, at that time the Foreign Ministry representative to the German military administration in Belgium and Northern France. Luther demanded of him an energisches Zugreifen (energetic approach) towards the Belgian Jews, because a 'decisive cleansing of Belgium of Jews would in any case have to take place sooner or later'.

Within the Foreign Ministry, Luther's position had initially grown stronger since he took office. He also rose further in the SA and in 1942 he reached the rank of SA-Brigadeführer. Luther's influence within the civil service went beyond the formal traditional powers of an undersecretary of state. He was the absolute ruler of Abteilung D, and flourished in his own 'empire. However, this did not last long. Already from late 1941 and reinforced from mid-1942, Luther's personal relationship with Von Ribbentrop was deteriorating and his position came under increasing pressure. His weight within the organization began to crumble and, in these circumstances, Luther took a path that would lead to his fall.

It is not clear from the sources what reasons were behind the estrangement between Luther and Von Ribbentrop. In any case, Luther's close and intensive contact with the powerful SS played a role. Von Ribbentrop viewed this with suspicion and increasing irritation. After all, the Außenmimnisterium was engaged in a constant battle of competence with the SS. Abteilung D always remained a subordinate partner of the SS, which certainly did not always consult the ministry in implementing the Endlösung, and sometimes even provided it with incorrect information. Von Ribbentrop felt that Luther neglected the interests of the ministry in this regard. Luther's contacts with Von Ribbentrop's rival Heinrich Himmler were a thorn in the minister's side.

Moreover, it was not insignificant that on a personal level Luther's relationship with Annelies von Ribbentrop was deteriorating. Luther had continued to work for her by helping her furnish her various homes and design her clothing. In Luther's eyes, though, in doing so she treated him condescendingly as a mere member of the household staff. Mrs. Von Ribbentrop, for her part, regarded Luther as an uppity boor.

Luther knew no scruples. Integrity was foreign to him. Even within the Nazi hierarchy of the Third Reich, filled with individuals who generally cared little for a minimum of moral sense, Luther never had a good reputation. Although he had devoted himself most fanatically to the Endlösung, more than all officials in the Außenmimnisterium, he was still accused of embezzling party funds at Zehlendorf.

This reputation for shadowy financial irregularities therefore continued to haunt Luther. On December 12, 1942, the top officials of the ministry launched an investigation into the financial and organizational state of the intelligence agency (Informationsstelle). That section had been established by Luther and fell under Abteilung D. The bureau was suspected of fraudulently squandering official funds. The in-depth investigation lasted for months despite objections, threats and opposition from Luther. One discovered 'a very unpleasant picture of internal conditions.' Incidentally, the investigation was never formally completed.

It is highly unlikely that this investigation could have taken place without Von Ribbentrop's consent. The minister had grown tired of Luther's hard-to-fathom financial mismanagement, and he had also received complaints that his undersecretary did not shy away from blackmailing employees. Now, Luther was certainly not the only official in the ministry who had ever been the subject of investigation, but unlike the career officials, he knew no prudence. Holding back and doubting was something alien to Luther, so he chose the frontal counterattack. His goal: to sidetrack his supreme chief Von Ribbentrop.

Luther realized that his now waning power and influence did not extend so far that he alone could overthrow the minister. He needed an ally, and he found one within the SS in the person of SS-Brigadeführer Walter Schellenberg, the head of the RSHA's foreign intelligence service. This was obvious, because the SS was the organization with which Luther had intensive contact as chief of Abteilung D, and Schellenberg was an important point of contact in this regard. Schellenberg also had his interests: as a matter of fact, he believed that Von Ribbentrop was not devoting enough effort in his foreign policy to ending what he saw as an unholy two-front war against the Western Allies and the Soviet Union which would inevitably lead to German defeat.

Walter Schellenberg, head of the RSHAs foreign intelligence service. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 101III-Alber-178-04A / Alber, Kurt / CC-BY-SA 3.0

It remains unclear how Luther and Schellenberg became aware of each other's plans, and which of the two made the first move toward the other. It is possible that Luther approached Schellenberg to secure the support of SS chief Himmler for his plans. It is also conceivable that Schellenberg asked Luther for incriminating material against Von Ribbentrop and assured him that with Himmler's support he would be able to overthrow the minister. German historian Hans-Jürgen Döscher, a specialist in the history of the Foreign Ministry at the time of National Socialism, supports the latter theory. According to him, the initiative for the coup came from Schellenberg, who himself wanted to succeed Von Ribbentrop as minister. He allegedly used Luther as a pawn within the ministry for this plan.

Luther was digging his own grave. In early 1943 he wrote an extensive memorandum in which he went into detail about what he believed to be Von Ribbentrop's mental weaknesses. He portrayed him as mentally ill and unfit for his position. Luther sent the document to Schellenberg, asking him to present it to Himmler as proof of Von Ribbentrop's unfitness for office. In doing so, Luther crossed a line. Even for Himmler, such blatant disloyalty to a minister was a serious violation of the leadership principle. In early February 1943, Himmler's adjutant,SS-Obergruppenführer Karl Wolff himself delivered the memorandum to Von Ribbentrop.

This sealed Luther's fate. The reprisal came quickly and was fatal. Luther was summoned to Von Ribbentrop's headquarters at the front where he was immediately arrested by the Gestapo on February 10, 1943. He was just able to make one last phone call to a close associate in Berlin. It was clear from his words that Luther understood his fate: 'Everything is over for us. Order two wreaths from Grieneisen (at the time the largest funeral director in Berlin). Walter Schellenberg, incidentally, escaped the dance: when it became clear that the plot failed, he dropped Luther without being exposed as a participant himself.

Von Ribbentrop's revenge was not limited to Luther and affected the entire ministry. After all, if you couldn't trust even Luther who could? Von Ribbentrop used the attempted coup against him as an occasion to cleanse the entire ministry. Abteilung D and such associated offices as the Informationsstelle and the Propagandastelle were dissolved. Functions of the Abteilung were transferred to existing or hastily created new bureaus.

Department heads and their subordinates were sacked. For instance, Luther's close associate Walter Büttner vanished to a front unit of the Waffen-SS, Referat D III chief Franz Rademacher was discharged and served the rest of the war as an officer in the Kriegsmarine. The highest official, Ernst von Weiszäcker, although not involved in the coup, was whisked away as ambassador to the Vatican. Another striking fate befell Undersecretary of State Ernst Woermann, the head of the Ministry's Political Department. He was ordered to embark on a U-boat that took him on a perilous journey halfway around the world via Malacca to China as ambassador to the Japanese puppet regime in Nanking.

Ernst von Weizsäcker, who was named ambassador to the Vatican after the failed coup. Source: Bundesarchiv

A distant and insignificant outpost was not for Luther. After his arrest, he was interrogated by Gestapo chief SS-Gruppenführer Heinrich Gestapo Müller, with whom he had sat at the table more than a year earlier during the Wannsee Conference. Luther was imprisoned in Sachsenhausen concentration camp north of Berlin, where he received preferential treatment as a privilegierter Schutzhäftling (prominent prisoner). Initially, Adolf Hitler wanted him hanged, but it never came to that. A letter from Heinrich Himmler dated June 5, 1944, to the chief of the Sicherheitspolizei and SD Ernst Kaltenbrunner reveals that Hitler personally - following a letter from Luther's wife and at Himmler's recommendation - had decided that Luther would be allowed to live with his wife in a house on the outskirts of the concentration camp during the course of that year. Luther spent his days taking care of the camp's vegetable garden.

Martin Luther made several failed attempts at suicide before the liberation of the camp by the Red Army on April 22, 1945. He died of a heart attack in Berlin on May 13, 1945. His untimely death at the age of 49 allowed him to dodge trial for his shared responsibility in the extermination of European Jews.

Definitielijst

- Abteilung

- Usually part of a Regiment and consisting of several companies. The smallest unit that could operate independently and maintain itself. In theory an Abteilung comprised 500-1,000 men.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Endlösung

- Euphemistic term for the final solution the Nazis had in store for the “Jewish problem”. Eventually the Endlösung would get the form of annihilating the entire Jewish people in extermination camps.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Kriegsmarine

- Germa navy. Part of the Wehrmacht next to Heer and Luftwaffe.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- moral

- The will of the troops/civilians to keep fighting.

- National Socialism

- A political ideology drawn up by Hitler based on the superiority of the German race, the leader principle and fierce nationalism that was fed by the hard Peace of Versailles. National socialism was anti-democratic and racist. The doctrine was elaborated in Mein Kampf and organised in the NSDAP. From 1933 to 1945 National socialism was the basis of totalitarian Germany.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- RSHA

- Reichssicherheitshauptamt. The central information and security service of the Third Reich.

- Socialism

- Political ideology aiming at slight or no class differences. Means of production are owned by the state. Evolved as a response to capitalism. Karl Marx tried to substantiate socialism scientific.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- two-front war

- State that occurs when a country is forced to fight a war on more than one border or different areas. During both wars, the First and second, Germany had to deal with a Western and an Eastern Front. During the World War 2 Germany even faced a third front, the Southern front, including the Mediterranean and North Africa.

- U-boat

- The German name for a submarine. German U-Boats (Submarines) played a very important role during the course of warfare until May 1943. Many cargo and passenger ships were torpedoed and sunk by these assassins of the sea.

- Waffen-SS

- Name of Military section of the SS.

- Wannsee Conference

- Conference at the Wannsee on 20 January 1942. The Nazi’s made final agreements about the extermination of Jews in Europe, the Final Solution (Ëndlösung).

Luther's copy of the Besprechungsprotokoll

Thirty numbered copies were made of the Besprechungsprotokoll of the Wannsee Conference (see: Wannseeprotokoll prepared by Adolf Eichmann) from a stenographic report, stamped Geheime Reichssache, the highest category of secrecy. Each of the conference participants naturally received a copy. That was fifteen people, and since a mailing list was missing, it remains unclear to whom the other fifteen copies were sent. An entry in his diary shows that at least propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels received a copy. The reason was that although his Secretary of State Leopold Gutterer had been invited to the conference, he had not shown up there. Other recipients remain unknown to this day.

Martin Luther received copy number 16 on March 2, 1942, which was placed in the archives of the Interior Department (Inlandsabteilung) of the Außenministerium after his failed coup. Because Luther was imprisoned in Sachsenhausen until the end of the war, the documents incriminating him were not destroyed. The Besprechungsprotokoll, along with other archives, was taken by officials to a more secure location in the Riesengebirge on the border of Poland and the Czech Republic in April 1944 because of the increasing Allied bombing of Berlin. From this location, the Geheime Reichssachen, including the Protokoll, were transferred in January 1945 to Bad Berka, south of Weimar in Thuringia. There everything - it involved more than 400 tons of Foreign Ministry archival material - fell into the hands of the advancing Americans. They then transferred this huge amount of paper to Marburg Castle in Hesse, as the Americans handed over the territory they had conquered in Thuringia to the Soviets.

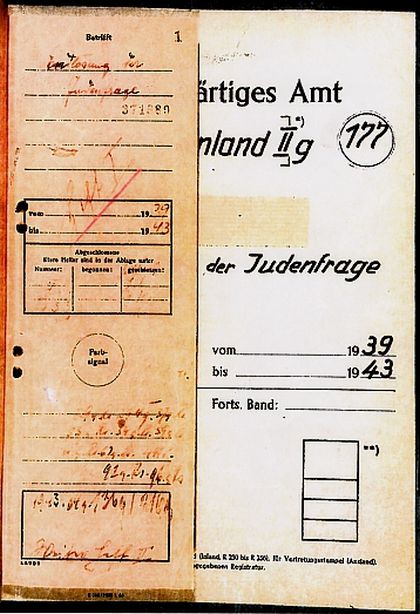

In Marburg followed the first analysis, arrangement and microfilming of the documents for use during the planned postwar trials of war criminals. Four crates of deeds were found along with documents zur Judenfrage. In one of the crates was a folder labeled Endlösung der Judenfrage. It contained the Besprechungsprotokoll; it went unnoticed.

The folder containing the Besprechungsprotokoll. Auswärtiges Amt, Inland IIg. Final Solution to the Judenfrage. 1939-1943. Source: www.ghwk.de

In early February 1946, the archives were transferred to Berlin and stored at Telefunken's Berlin-Lichterfelde plant in the city's American sector. There the documents were further examined and microfilmed. It was not until December 4, 1946, that Luther's copy of the Besprechungsprotokoll was first discovered, the only one known not to have been destroyed during the war.

The discovery of the document came too late for use in the International Military Tribunal against the twenty-four Nazi leaders; sentences had already been handed down on Oct. 1, 1946. It did play an important role in the so-called Wilhelmstraßen-Prozess, which was conducted in Nuremberg from November 1947 to December 1949 against senior officials of the various ministries. Because of his untimely death, Luther escaped this trial, but the irony of history is it was precisely his copy of the Besprechungsprotokoll that contributed to the conviction of his former colleagues.

In the summer of 1948, during the Berlin blockade, the complete archive was transferred to Whaddon Hall country house in Buckinghamshire, England. A second microfilming followed there. Finally, between late 1956 and early 1959, all records were returned to the Political Archive of the German Foreign Ministry, initially located in Bonn and after the German reunification in Berlin. To this day, the only surviving copy of the Besprechungsprotokoll, Martin Luther's copy, is located there.

Definitielijst

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Wannsee Conference

- Conference at the Wannsee on 20 January 1942. The Nazi’s made final agreements about the extermination of Jews in Europe, the Final Solution (Ëndlösung).

Information

- Article by:

- Robert Jan Noks

- Translated by:

- Fernando Lynch

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- CONZE, ECKART e.a., Das Amt und die Vergangenheit, Karl Blessing Verlag, München, 2010.

- JASCH, HANS-CHRISTIAN & KREUTZMüLLER, CHRISTOPH, The Participants, Berghahn Books, New York, 2017.

- KLEE, ERNST, Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich: Wer war was vor und nach 1945, Fisher TB, Frankfurt, 2007.

- LEHRER, STEVEN, Wannsee House and the Holocaust, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, North Carolina, 2000.

- LONGERICH, PETER, Wannsee, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2021.

- MEINHARDT, CAROLINE, Das Auswärtige Amt bei der Wannseekonferenz, GRIN Verlag, 2018.

- PAEHLER, KATRIN, The Third Reich's Intelligence Services, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2017.

- ROSEMAN, MARK, The Villa, The Lake, The Meeting, Penguin Books, London, 2003.

- SEABURY, PAUL, The Wilhelmstrasse, University of California Press, Berkeley/Los Angeles, 1954.

- YOUNG, WILLIAM, German Diplomatic Relations 1871-1945, iUniverse, Inc., New York/Lincoln/Shanghai, 2006.

- de.wikipedia - Martin Luther

- de.wikipedia - Auswärtiges Amt, Deutsches Reich, Zeit des Nationalsozialismus

- de.wikipedia - Rudolf Hess, Reichsminister und Stellvertreter des Führers

- de.wikipedia - Stab des Stellvertreters des Führers

- de.wikipedia - Martin Bormann, Reichsleiter und Stabsleiter von Rudolf Hess

- en.wikipedia - Joachim von Ribbentrop

- en.wikipedia - Martin Luther

- dbpedia.org

- timenote.info

- oorlogsbronnen.nl

- de-academic.com

- archiv.diplo.de

- ghwk.de