Introduction

On January 20, 1942, a conference was held in a villa on the Wannsee near Berlin. Subject of discussion was the Endlösubg der Judenfrage or the final solution of the Jewish problem. Fourteen high ranking officials of the various ministerial departments and SS officers, chaired by SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt, discussed the plan to exterminate all European Jews. Long after the war, it was assumed that during his conference, the decision to set this plan in motion was taken. Although this has long been denied by historians, this is still wrongly assumed by many today

Although this wasn't the decisive moment in the history of the Holocaust, this conference is an important symbol today. It offers an inside view into the organization of the Endlösung and shows how a group of intelligent, civilized officials in the luxurious environment in a beautiful villa in one of the most modern capitals of Europe, discussed the destiny of some 11 million Jews of whom ultimately some 6 million were murdered. The minutes of this conference are one of the most telling written evidence of the Endlösung.

Definitielijst

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

Beginning of the mass murders

The year 1941 was a decisive year for the realization of the Nazi plan to murder all European Jews. That year, Nazi officials accepted mass murder as a solution of the Jewish problem that had been on the agenda since Adolf Hitler seized power in January 1933. During the pre-war years, Jews were gradually isolated from German society. In September 1935, the Nürnberger Rassengesetze (racial laws) had been issued, robbing the Jews of their civil rights. Following Kristallnacht of November 1938, numerous measures were taken to completely isolate Jews, socially and economically, from German society.

As a result of the anti-Semitic policy and under pressure by the Nazis, some 537,000 Jews emigrated from the Third Reich until Hitler prohibited further emigration by Jews on October 31, 1941. Another way to tackle the Jewish problem was chosen: deportation to ghettoes in Poland and occupied areas in the Soviet union. There, they usually lived in deplorable conditions and Jews fit for labor were deployed as slaves in the armament industry.

Meanwhile, German troops had invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. Behind the frontline troops, the so-called Einsatzgruppen caused a blood bath among the Jewish population

Execution carried out by a member of an Einsatzgruppe in the Ukraine, 1942. Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

These murder squads were under command of Reinhard Heydrich. Initially, only Jewish males were being executed but pursuant to an order by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, from July 1942 onwards, females and children were being executed as well. From the spring of 1941 onwards, the mass slaughter on the Eastern Front was being emulated in the ghettoes where local Nazi officials found themselves confronted with overpopulation and an ‘excess’ of Jews unfit for labor. In order to create space, in November 1941 12,000 Jews were murdered in Minsk to make room for Jews from Hamburg. The same occurred when on November 12, 1941, Himmler ordered the evacuation of the ghetto in Riga to make room for the Jews who had been deported from Berlin, the Rhineland and Westphalia. Throughout November and December some 20,000 Jews were executed here, among them German Jews.

Execution of Jews turned out to be a heavy mental burden for the members of the Einsatzgruppen and moreover, from the Nazi point of view, it wasn’t sufficiently effective. Therefore, experiments were conducted with other methods of killing. Thereby, the experience gained from the T-4 euthanasia program, launched in 1939, was very useful. Mentally and physically handicapped persons were murdered in order not to weaken the Aryan race and at the same time, dispose of unnütze Esser or useless eaters in Germany. Initially, these were murdered by administering injections with chemicals but in a later phase, this was done in special euthanasia centers where they were gassed with carbon monoxide in gas chambers. From the end of 1939 until June 1940, gas trucks were deployed. In these trucks, the victims were gassed in the cargo space with the exhaust fumes from the engine. These vans were deployed in Poltava for the first time as an alternative for the mass executions on the Eastern Front but in Chelmno, the first extermination center of the Nazis, this method was used as well.

This center in Chelmno in the Wartheland, (an administrative district, established by the Germans and including Poznan, Lodz and Warsaw) was established in particular to kill ‘unproductive’ Jews from the ghetto of Lodz. The first of them arrived on December 7, 1941 and gassing started the next day. In the southeast of the Lublin district in the General Government, construction of an extermination camp was started on November 1 in Belzec as ordered by local SS and chief of police Odilo Globocnik. It was the prototype of the extermination camps Sobibor and Treblinka, which were also established in the General Government in the spring of 1942. In all three camps, Jews were to be gassed with carbon monoxide in gas chambers. Prior to the Wannsee Conference, the gas chambers in Belzec had been tested with various groups of Jews. On September 5 and 6, 1941, experiments with gassing were conducted in concentration camp Auschwitz, not with carbon monoxide though but with the pesticide Zyklon-B. In addition to Jews, the victims were also Russian prisoners-of-war.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Rhineland

- German-speaking demilitarized area on the right bank of the Rhine which was occupied by Adolf Hitler in 1936 after World War 1.

- Soviet union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Zyklon-B

- Poison gas that was systematically used in German extermination camps, primarily to murder Jews.

Decision making

In 1941, the mass murder was already in full swing. Towards the end of he year, various experiments with gassing had proved successful. At that moment though, there was no question yet of an all-encompassing plan to exterminate all European Jews. These were mostly separate initiatives, carried out with permission or approval from higher authority but those were not yet part of an all-encompassing plan. The first step towards such a plan had already been taken by Reichsmarschal Hermann Göring on July 31, 1941, when he ordered Heydrich ‘to take all required measures […] for the total solution of the Jewish problem within Germany’s sphere of influence in Europe.’ With this, he granted Heydrich and his boss a free hand to see to the Endlösung der Judenfrage.

Hermann Göring ordered Reinhard Heydrich to prepare for the Endlösung der Judenfrage. Source: Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

It isn't likely that total annihilation of the Jews in Europe was meant at that moment. Hitler probably took this definite decision as late as December 7, 1941 after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and Germany had declared war on the United States on the 11th. According to Nazi views the Jews, as alleged fifth column of capitalism and Communism, posed a greater danger to Germany as the country was now at war with both the Soviet Union and the USA. The failure to capture Moscow in November and December may have played a role as well because with this, the hope for a quick victory against the Soviet Union had gone up in smoke. Plans to deport the Jews to camps in Siberia were therefore not feasible in the short run.

One day after the aforementioned declaration, Hitler delivered a speech in the Reichstag in which he, according to Joseph Goebbels, made firm statements concerning the Jewish problem. ‘Regarding the Jewish problem, the Führer has decided to make a clean sweep,’ the minister of propaganda wrote in his diary. ‘He had predicted the Jews would be annihilated once they triggered a world war again. This was no small talk. We are now confronted with a global war and the necessary consequence is the extermination of the Jews.’ Hans Frank, governor of the General Government was present as well during this speech. On December 16, 1942 he delivered a speech himself to his associates in Krakow, declaring he wanted the Jews to be deported out of the General Government. ‘But what should happen to the Jews,’ he asked openly. ‘In Berlin we were told, why take these problems upon ourselves? We can’t do anything with them in the Ostland or in the Reichskommissariat Liquidate them yourselves We must exterminate the Jews wherever we find them and wherever we can to maintain the regime here as well. The General Government must be made free of Jews, just like the Reich.’

Historians remain doubtful about the question when the decision was taken to exterminate all European Jews but they agree this decision wasn't taken during the Wannsee conference. The Nazi officials who were present, were not high ranking enough to come to such a decision. This decision must have been taken by Hitler or at least approved by him first. Before he took power, the Jewish question was one of his most important goals and with the outbreak of a global war, nothing stood in the way of a radical solution anymore. In December 1941, Himmler had various talks with Hitler, unfortunately minutes are not available, where the Jewish question must have been discussed. ‘Jewish question - ausrotten wie Partizane’ (destroy like partisans), the SS leader noted in his agenda after a talk with Hitler on December 18.

Although we will probably never be sure exactly when the decision to murder all European Jews was taken, 1942 was the year in which the extermination camps became operational and in which deportation and extermination of Jews were no longer separate initiatives but a general policy coordinated by the SS. Until then, the various party and government departments had stood in each other’s way frequently when tackling the Jewish question. A good example is the conflict between Governor Hans Frank and the SS which unfolded since the Jews were being deported from the Reich to the General Government. Frank objected to this because he didn't want his domain to be used as a ‘racial garbage dump.’ The relation between the RSHA and the Innenministerium were tiresome as well because it wasn't clear who had authority over Jews of mixed race (Mischlinge.) In order to create clarity for the parties involved, to solve arguments of competence and streamline responsibilities, Heydrich called the Wannsee conference; not to decide to launch the Endlösung as that was already in progress.

Definitielijst

- Communism

- Political ideology originating from the work of Karl Marx “Das Kapital” written in 1848 as a reaction to the so-called class struggle between the proletariat (labourers) and the bourgeoisie. According to Marx the proletariat would take over power from the well-to-do classes though a revolution. The communist movement aspires an ideal situation where the means of production and the means of consumption are common property of all citizens. This should end poverty and inequality (communis = common).

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Liquidate

- Annihilate, terminate, destroy.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- RSHA

- Reichssicherheitshauptamt. The central information and security service of the Third Reich.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wannsee conference

- Conference at the Wannsee on 20 January 1942. The Nazi’s made final agreements about the extermination of Jews in Europe, the Final Solution (Ëndlösung).

Location and participants

Heydrich’s invitations for the Wannsee Conference were sent between November 29 and December 1, 1941. Below is the translation of the invitation to Martin Luther, State undersecretary of the Außenministerium:

’Liebe Parteigenosse Luther,

On July 31, 1941, the Reichsmarschal des Groß Deutschen Reiches has ordered me to make all necessary organizational and technical preparations for an all-encompassing solution of the Jewish problem, in cooperation with the other central authorities and submit an overall proposal to him. Regarding the exceptional importance of these questions and with the intention to reach a mutual stand point of the central organizations involved, I propose to call a meeting to discuss these issues. This is so important because since October 15, 1941, Jews from the Reichsgebiet including the Protektorat Bohemia and Moravia have frequently been evacuated to the east. I therefore invite you to a meeting with breakfast on December 9 at 12:00 hrs.’

As a result of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, the conference was postponed to January 20, 1942 because the presence of some of the invited was required elsewhere. Assuming the decision of total annihilation of Jews in Europe was taken after the attack, the question arises what would have been discussed on the 9th but this can only be guessed at.

Initially, the conference was to be held in the building of Interpol, Am Kleiner Wannsee 16, but it was relocated to the guesthouse of the Sicherheitspolizei, Am Großen Wannsee 56-58. This guesthouse was located in a villa in Wannsee, a suburb in the southwest of Berlin and was named after the two lakes in the vicinity, the Große and Kleine Wannsee. Strandbad Wannsee on the east bank of the larger lake is one of the largest open air bathing sites in Europe. At the time of the Third Reich, the exclusive location and the proximity of the government center drew many prominent Nazis to Wannsee. Joseph Goebbels and Albert Speer, to name just a few, had a house here. The SS also housed various departments in the neighborhood. The villa Am Großen Wannsee 56-58 had been the property of a right wing industrialist, Friedrich Minoux, who had sold the villa to the Stiftung Nordhav, a charity institution that officially occupied itself with acquiring vacation and recuperation homes for members of the SD. In 1941, the villa was transferred and converted into a guesthouse for high ranking members of the Sicherheitspolizei and the Sicherheitsdienst having to spend the night in Berlin.

Not everyone, who had been invited for December 9, was present on January 20. Both Leopold Gutterer of the Propagandaministerium and SS-Gruppenführer Ulrich Greifelt, leader of the Hauptamt Reichskommissariat für die Festigung Deutsches Volkstums were unable to attend. The two most important leaders of the General Government, Governor Hans Frank and HSSPF SS-Obergruppenführer Friedrich Krüger had sent deputies, Dr. Joseph Bühler and SS-Oberführer Dr Karl Eberhard Schöngarth respectively. Franz Schleber, deputy Justizminister, dispatched a representative, Roland Freisler. Gestapo chief SS-Gruppenführer Heinrich Müller, SS-Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann and SS-Sturmbannführer Dr Rudolph Lange were not mentioned on the guest list but were present to support their chief.

Below the list of all present on January 20:

- Gauleiter Dr. Alfred Meyer, Staatssekretär and deputy Reichsminister of the Reichsministerium für den besetzen Gebieten im Osten,

- Reichsamtsleiter Dr. Georg Leibbrandt, chief of the political department of the Reichsministerium für den besetzen Gebieten im Osten,

- Staatssekretär Dr. Wilhelm Stuckart, Staatssekretär des Reichsinnenministeriums,

- Staatssekretär Erich Neumann of Hermann Göring, responsible for the Four-Year-Plan,

- Staatssekretär Dr. Roland Freisler of the Reichsjustizministerium,

- Staatssekretär Dr. Josef Bühler of the office of the General Government in Krakow, Poland,

- Unterstaatssekretär Martin Luther, of the Reichsaußenministerium,

- SS-Oberführer Dr. Gerhard Klopfer, chief of the Staatsrechtliche Abteilung III of the NSDAP Parteikanzlei,

- Ministerialdirektor Friedrich Kritzinger, deputy chief of the Reichskanzlei, responsible for Jewish problems,

- SS-Gruppenführer Otto Hofmann, chief of the Rasse und Siedlungshauptamt of the SS,

- SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt of the SS,

- SS-Gruppenführer

- Heinrich Müller, chief of the Gestapo within the Reichssicherheitshauptamt,

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann, chief of Referat IV B 4, Jewish Affairs and Evacuation within the Reichssicherheitshauptamt,

- SS-Oberführer Dr. Karl Eberhard Schöngarth, commander of the Sicherheitspolizei and Sicherheitsdienst in the General Government and

- SS-Sturmbannführer Dr. Rudolf Lange, commander of the SIPO and SD in Latvia and deputy commander of the SIPO and SD in the Reichskommissariat Ostland.

All those present represented government and party organs who were involved in or responsible for the Jewish question in one way or another. The Justizministerium and the Innenminsterium had been responsible for drafting of and issuing the Nürnberger Rassengesetze in 1935. Both ministeries were involved in shaping government policy as to Jews with mixed ancestry, (Mischlinge) and Jews from mixed marriages, (Mischehe). Their power had to be curtailed. On November 24, 1941, Himmler had already discussed this with State secretary Stuckart of the Innenministerium Point three of Himmler’s agenda was: ‘Jewish question - Mine.’

The Außenministerium felt partly responsible for the removal of Jews from countries occupied by Germany but also urged to incite European allies to deport their Jewish citizens. Even before the conference, State undersecretary Martin Luther had submitted a list to Heydrich with eight wishes and ideas pertaining to the Jewish question in Europe. Luther advocated for instance to deport all Jews from the Reich, including those from Croatia, Slovakia and Romania to the east. He also wanted to encourage the Bulgarian and Hungarian authorities to introduce anti-Semitic legislation like the Nuremberger laws. Other European governments would have to be coaxed accordingly.

Just like the Innenministerium, party leaders in the General Government and the occupied areas in the Soviet Union, concerned themselves with plans to make their territories Judenfrei or free of Jews. The main reason for their invitation was that Heydrich wished to make it clear to them that not they but he bore the ultimate responsibility for the removal of Jews. This was particularly necessary in the General Government, because shortly before the conference, Höhere SS und Polizeiführer or HSSPF Krüger had complained to Heydrich about the opposition he encountered from Governor Hans Frank.

The presence of a relatively high number of SS members undoubtedly served to intimidate hesitant representatives of government and party or at least to lend Heydrich’s words more power of persuasion. Whereas the other representatives mainly concerned themselves with issuing laws and orders, the members of the SS were experts in the field who were directly as well as indirectly involved in the emigration policy and the extermination in the east. Dr Schöngarth as well as Dr Lange, in their allocated areas, had collaborated with or given orders to execute Jews in their masses. In the years before the Wannsee Conference, Adolf Eichmann had been engaged in for instance the emigration policy and had become an expert on Jewish affairs.

Most of those present were young and highly educated. Almost half of them hadn't yet reached the age of 40 and only two were over 50. Of the 15 present, eight of them had a doctors title. Among the academics, the lawyers formed a majority. Most of those present were fanatic Nazis who eagerly embraced the National socialist world view or opportunists who conformed themselves with full devotion to new policy and orders when the Nazis took power. It goes without saying that not a single one of those present would have spoken up for the Jews. Not only because they didn't want to endanger their careers but also because they had supported the radical anti-Jewish policy so far, had collaborated with it or had urged even stronger measures.

Definitielijst

- Abteilung

- Usually part of a Regiment and consisting of several companies. The smallest unit that could operate independently and maintain itself. In theory an Abteilung comprised 500-1,000 men.

- Gauleiter

- Leader and representative of the NSDAP of a Gau.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- SIPO

- ”Sicherheitspolizei”. Combination (since 1936) of the Gestapo and criminal police.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

Heydrich’s explanation

At the conference, many subjects were discussed but the major part of the meeting was an explanation by Reinhard Heydrich, informing those present about the new, definite policy concerning the Jews. That conclusion can at least be drawn from the minutes of the conference - also called the Wannsee Protocol. In March 1947, associates of the American prosecutor at the Nuremberg trial found a copy by accident in a folder at the Außenministerium. The minutes are no verbatim representation of what was actually said but are a formulation of plans and problems that were discussed. For the most part it is a presentation of Heydrich’s words. It can't be established exactly how frequently he was interrupted or what reactions his statements evoked but we can conclude that most decisions and plans couldn't be undone. Those invited were just listeners who only had something to say about details. The mood was relaxed. ‘It proceeded very quietly, very friendly, very polite and courteous; not many words were wasted on the subject, cognac was served by orderlies and then it was all over,’ Adolf Eichmann recalled after the war.

Heydrich began with the announcement that on July 31, 1941 he had been named by Göring Authorized Representative for the preparation of the final solution of the European Jewish question. He stressed that the organizational leadership, regardless of territorial boundaries, was in the hands of the Reichsführer-SS and chief of the German police Heinrich Himmler. Next he explained what measures had already been taken. He informed them that up to October 31, 1941, a total of 537,000 Jews had been incited to emigrate, despite the inherent problems such as the lack of ship capacity, limitations on emigration and blockades. Due to the dangers of emigration in war times and with regard to the possibilities in the east, so Heydrich declared, Jews were no longer allowed to emigrate. The Führer had given permission for the ‘evacuation’ of the Jews to the east. This was only a fallback option but practical experience had been gained which would lead to the Endlösung. With these ‘practical experiences’ he probably meant the experiments with gassings in Chelmno, Belzec and Auschwitz.

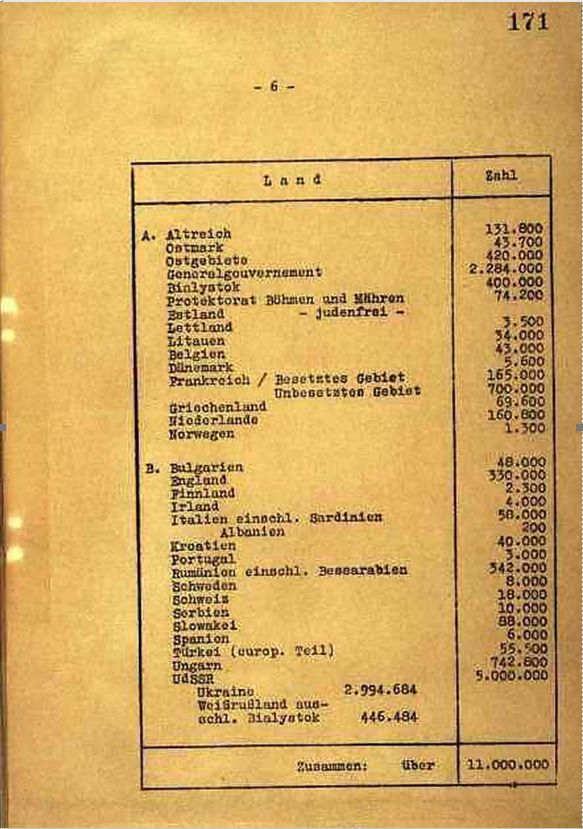

The entire operation would encompass some 11 million Jews. In the minutes, we find a chart showing in which countries these Jews were living:

Included are countries within the German Empire and those occupied by Germany but also allies, hostile and neutral states such as Hungary, Great Britain, Portugal and Switzerland. The message was clear: the whole of Europe, even those outside direct reach of Germany, was to be made Judenfrei in the end. The plans even reached outside the European borders because all Jews in the Asian part of the Soviet Union would be victims as well. Vichy-France also included the Jews in the French colonies in North-Africa.

Nowhere in the minutes, it is stated explicitly that European Jews would be murdered in extermination camps in Poland. As 30 copies were to be distributed among the various agencies involved, the text had been written in veiled language on purpose in order to prevent the secret plans from being openly spread around on paper for non-informed readers. During his trial in Jerusalem, Adolf Eichmann admitted that during the conference, Töten und Eliminieren und Vernichten had been discussed freely, ‘I can't recall all the details, Mr President,’ Eichmann testified, ‘but I know the gentlemen were sitting together and calling a spade a spade, - not the words I noted in the minutes but in unveiled language, - naming the issues by name and not hiding anything. I wouldn't have remembered this if I wouldn't know that I said to myself then "Well, well, look at Stuckart, judicially always meticulous, a nit-pickier and hear him now. All their words had nothing formal anymore."’ During the Nuremberg trial, Stuckart and Kritzinger denied that in Wannsee mass murder had been openly discussed but notwithstanding the veiled language, the text of the minutes is crystal clear.

We read in the minutes that men and women were to be separated and subsequently those who were able to work, were to be put to work building roads. Heydrich probably meant construction of the Durchgangsstraße IV, a road (railway?) between Germany and the eastern front which was already under construction. In the process, a an important part of the Jew would drop out by natürliche Verminderung, natural decrease which could have meant nothing else other than death. The ‘possibly remaining part’ had to be entsprechend behandelt or treated accordingly. These Jews who had survived hard labor were considered the ‘nucleus of a new Jewish generation’ and reproduction of a strong Jewish community had to be avoided. When Israeli interrogators asked Eichmann what was meant by entsprechend behandelt, he stammered: ‘Murdered, murdered of course.’

Not a single word was uttered about what had to be done with Jewish children and the adults considered unfit for work. This omission was significant because what value did those unfit for labor have when even all those fit for labor perished or were killed? Without it being mentioned explicitly, the conclusion is clear: they would be murdered priorto the Jews fit for labor. For the time being, an exception was made for Jews over 65 (30% of the Jews living in Germany and Austria): they would be transferred to a ghetto for the elderly for which Theresienstadt was intended. The same exception applied to Jews who had severely maimed during the First World War and those who had been decorated with for instance the Ehrenkreuz. In the end, this privilege meant little because out of the 140,000 Jews deported to Theresienstadt, 33,000 would die on the spot and 88,000 were deported to extermination camps of which only 3,000 would survive.

The beginning of the ‘evacuation’ was highly dependent on military developments, we read in the minutes. This probably meant that evacuation from countries still outside Germany’s sphere of influence could only begin after a military victory over these countries. The German Empire, including the Protektorat Bohemia and Moravia would come first. This operation would have priority ‘if only because of the housing problems and other social-political needs’. This meant for instance the shortage of housing due to Allied bombardments. In Slovakia and Croatia, this issue wasn't particularly difficult as the ‘essential problems in this case[…] had already been brought to a solution.’ In Romania, people had been appointed meanwhile to tackle the Jewish problem but an advisor for Jewish affairs had to be sent to Hungary on short notice. In Italy, consultation would have to be started with the Italian police. Rounding up and deporting Jews from occupied and non-occupied France would pose no problems. State secretary Martin Luther did envisage problems in the northern countries and he proposed to postpone the deportations there. After all, there were few Jews living there and ‘this delay didn't cause a significant limitation at all’. In southeastern and western Europe the representatives of the Außenminsterium foresaw few problems.

Definitielijst

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Theresienstadt

- City in the Czech Republic. Here the Nazis established a model concentration camp.

Mischlinge and Mischehe

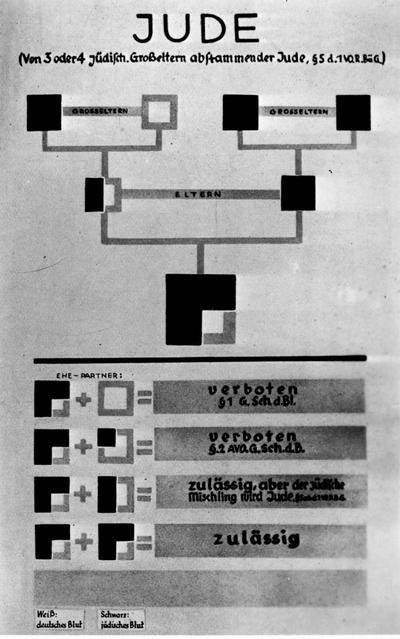

Once the framework of the Endlösung had been explained by Heydrich and the process in the various countries had been discussed, there was discussion about the way how to handle Jews who, according to the Nuremberg Laws were not considered Volljude. Whether someone was considered a Jew depended first and foremost on his ancestry, with Jewish religion and world view in second place.

Full Jews had three or four Jewish grandparents but also people with two grandparents who were married to a Jew or religiously active Jews were placed in this category. In Germany, Jews constituted a well-assimilated section of the population and the many mixed marriages between Jews and non-Jews had produced children with only two grandparents or one in the past decades. Mischlinge or Jews of mixed ancestry in the first degree had two Jewish grandparents but were no followers of the Jewish faith and hadn't been married to a Jew as of September 15, 1935. Jews of mixed ancestry in the second degree had only one Jewish grandparent but Aryans who had been married to a Jew were included in this category as well. In 1939. the Germans had calculated that 52,006 Jews of mixed ancestry in the first degree and 32,669 in the second, lived in the Altreich (Germany within the borders of 1937). Over 90% of these had been converted to Christianity.

SS-Gruppenführer Otto Hofmann of the RuSHA. He offered Mischlinge a choice: ‘evacuation’ or sterilization. This photo was taken in the Netherlands in July 1942. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-B26445 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Heydrich opted for a radical approach as the more Mischlinge received the same treatment as full Jews, the more power he had. As far as Heydrich was concerned, first degree >Mischlinge were considered equal to full Jews except those who were married to an Aryan in which marriage children had been born and those who had been exempted by high party or government agencies. Those exempted from ‘evacuation’ were to be sterilized voluntarily ‘as a condition to be permitted to live in the Reich.’ Second degree Mischlinge had to be considered to be of German blood, except in a few cases. These were those from a bastard marriage (if both partners were Mischlinge; persons with a Jewish appearance or with a certificate showing that ‘he or she feels and behaves like a Jew.’ When a second degree Mischling was married to an Aryan, these exceptions would be dropped and the quarter Jew was exempted from deportation.

Then there were the marriages between full Jews or first degree Mischlinge and Aryans or second degree Mischlinge. According to Nazi calculations from 1939, there were 20,454 mixed marriages within the Great German Empire (at the time including Austria and the Sudetenland). Heydrich now had to reckon with the Aryan partner and non-Jewish family members. If their spouse or next of kin would be deported, this would cause much commotion. This had to be prevented. In order not to endanger the Endlösung and prevent it from ending like the euthanasia program which had been officially cancelled on August 24, 1941 due to pressure from the Church and family members of the victims. As to marriages between full Jews and Aryans, in each case it had to be considered whether the Jewish partner would be ‘evacuated’ or transferred to a ghetto for the elderly. The choice depended on the reaction of the Aryan partner. The same treatment applied to first degree Mischlinge married to an Aryan and the marriage remaining childless. In case such a marriage did produce children, the first degree person wouldn't be deported, provided the children were not considered Jews. If in exceptional situations, this was the case then the parent as well as the children would be deported or transferred to a ghetto. In marriages between two first degree Mischlinge or a full Jew, both partners as well as the children would be deported or transferred to a ghetto for the elderly. The same applied to marriages between first and second degree Mischlinge as children from such marriages displayed, so the minutes read: ‘a stronger influence of Jewish blood.’

Wilhelm Stuckart, state secretary of the Innenministerium. He advocated compulsory sterilization of all Mischlinge. Source: Haus der Wannsee-Konferenz Gedenk- und Bildungsstätte

Not all of those present supported Heydrich’s plans. Otto Hofmann advocated large scale sterilization of Mischlinge. They would have to opt for ‘evacuation’ or sterilization themselves. Hofmann was convinced they would sooner opt for sterilization. Another reference to the fact that evacuation meant nothing other than extermination because would people in their masses opt for sterilization above relocation, the judges argued during the Nuremberg trial. State secretary Wilhelm Stuckart went even further and pleaded mandatory sterilization for all Mischlinge because Heydrich’s plans ‘would entail endless administrative work.’ With this he deviated from the line of his ministry which had advocated so far to grant Mischlinge a separate status, placing them outside the measures of the Endlösung. Furthermore he intended to dissolve all mixed marriages by law. During the Nuremberg trial, Stuckart defended his views by testifying he had tried to prevent the ‘evacuation’ of Mischlinge. he claimed he had wanted to buy time because he knew that his proposed sterilization would be technically impossible. It is probably more likely he made his proposals to maintain the decreasing influence on the Jewish problem of his ministry a little.

Definitielijst

- Endlösung

- Euphemistic term for the final solution the Nazis had in store for the “Jewish problem”. Eventually the Endlösung would get the form of annihilating the entire Jewish people in extermination camps.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Nuremberg Laws

- Laws promulgated by Hitler on the party convention on 15 September 1935. These laws alter alia included regulations about marriage and intercourse between Jews and non-Jews. Jews were deprived of German citizenship. Also known as the racial laws.

Closure of the conference

At the end of the conference, some of those present were given the opportunity to have their own say. State secretary Erich Neumann of the Four Year Plan was worried about the effect ‘evacuation’ would have on economic life. He wanted the Jews, who worked in the armaments industry within the framework of the Arbeitseinsatz, not to be deported, at least as long as replacements were unavailable. Heydrich could put him at ease because based on his directives, such Jews wouldn't be deported. Next State secretary Joseph Bühler pleaded to deport the Jews from the General Government first. He said in particular the Jews here posed an ‘all-encompassing danger’ and their ‘continuous black trade kept disturbing the economic structure of the country.’ Of the nearly 2.5 million Jews living here, he said, the majority would be unfit for labor anyway. He motivated his plea further by saying that the problem of transport didn't play an all-encompassing role in the General Government. He probably referred to the country already having one extermination camp at its disposal, Belzec, and he probably knew about the plan to establish another two.

Bühler’s plea was a token that he fully supported Heydrich’s plan but it must have pleased Heydrich even more that Bühler subsequently made a declaration of loyalty to him. In fact, the state secretary declared that ‘the central leadership of the solution of the Jewish problem in the General Government was in the hands of the chief of the SIPO and SD and that his work would be fully supported by the official agencies in the General Government’. This was exactly what Heydrich had wanted after the problems he had experienced with the administration of the country. This declaration was therefore explicitly included in the minutes. Bühler didn't go after Heydrich’s sympathy but wanted his territory the first to be made Judenfrei. He got what he wanted as from the spring onwards, the Jews from the country where murdered in the extermination camps during Aktion Reinhard.

The last subject discussed, according to the minute, was ‘the various methods to the solution’. It is unknown whether the extermination camps or the gas chambers were discussed. Bühler and Alfred Meyer however stressed that during the preparations for the Endlösung ‘in the areas involved,[…] unrest among the population should be avoided.’ This probably meant that the extermination program should not become known by the indigenous population of the General Government and the occupied areas of the Soviet Union. Subsequently, the meeting was closed but not before Heydrich expressly indicated that the participants ‘would lend him the necessary support in the execution of the work for the Endlösung.’ With that he made them accessories to mass murder and was exactly what he wanted.

Definitielijst

- Arbeitseinsatz

- “Labour deployment”. Forced deployment in the German industry. Approximately 11 million European citizens were rounded up and deployed into forced labour in the Third Reich. Not to be confused with the Arbeidsdienst or labour service, an organisation for national-socialist education for Dutch youngsters.

- Four Year Plan

- A German economic plan focussing at all sectors of the economy whereby established production goals had to be achieved in four years time.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- SIPO

- ”Sicherheitspolizei”. Combination (since 1936) of the Gestapo and criminal police.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

What was achieved?

After the conference, Heydrich made a relaxed impression. During his trial in Jerusalem, Adolf Eichmann testified how he with Heydrich and Müller was sitting at the fire in the guesthouse, smoking and drinking cognac. ‘We were sitting together cozily,’ so Eichmann said, ‘not to talk about the subjects again but to get a little rest after the long exacting hours.’ Heydrich must have been pleased about the outcome of the conference. His exclusive authority as to the Endlösung had been accepted and even the party leaders in the General Government acknowledged his superior role in this explicitly. Nobody had protested against the framework of his plans and cooperation of the various party and government agencies was guaranteed.

Regarding the Mischlinge and the mixed marriages, a breakthrough hadn't yet been reached. These issues were discussed during two follow-up meetings at RSHA HQ. The first was held on March 6, 1942 but didn't produce a definite agreement. Wilhelm Stuckart’s proposal to sterilize first degree Mischlinge and dissolve mixed marriages after the Aryan partner had had sufficient time to decide on divorce, was accepted in principle but right after the meeting this was challenged by Justizminister Franz Schlegelberger. A second meeting was called on October 27 but the participants didn't get beyond the proposals of March 6.

There were various reasons for not executing Stuckart’s proposals. First it turned out that mass sterilization was impossible to achieve although in the summer of 1942 proposals were made that treatment with X-rays might be effective. Secondly, the ministries of Justice and Propaganda were worried about the effect of compulsory divorce. The Propagandaministerium was afraid of strong objection from the Catholic church and the Justizministerium foresaw legal hurdles. The deciding factor was that Hans Lammers, chief of the Reichskanzlei, postponed the plans because he understood from signals from Hitler that the latter didn't wish to be bothered by such a proposal in war time. In October 1943, an agreement was ultimately reached between the Justizministerium and the SS not to deport German Mischlinge during the war. Most of them wouldn't be deported after all.

Jews from mixed marriages would also be left alone for the most part. When in February 1943, some 1,800 Jewish men, most of them married to Aryan women, were picked up, their wives protested. They assembled in front of a building on Rosenstraße where their husbands were detained awaiting deportation. The protest lasted a few days but in the end, Joseph Goebbels, Gauleiter of Berlin in addition to his being Propagandaminister, gave in to prevent further escalation. He was afraid public sentiment would turn against the regime if guards would have been ordered to open fire on Aryan women. It didn't go so easily with all Jews from mixed marriages. In December 1943, deportation of previously privileged women was begun when their husbands had died. From January 1945 onwards, some Jewish women with their Aryan husbands still alive, were also deported.

Heydrich will not have considered the failure of his proposals at the Wannsee Conference regarding Mischlinge and mixed marriages as a major defeat. The agreements in Wannsee only pertained to the Jews within the Reich because the ministries of Justice and Internal Affairs had no authority outside Germany. Generally speaking, the SS had more room to maneuver there to tackle the issues as they wished or Jews were just less assimilated so there was hardly any question of Jews of mixed ancestry or mixed marriages.

Definitielijst

- Gauleiter

- Leader and representative of the NSDAP of a Gau.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- RSHA

- Reichssicherheitshauptamt. The central information and security service of the Third Reich.

After the conference

One day after the conference, Reinhard Heydrich made his report to Heinrich Himmler. Once nothing seemed to stand in their way, they could finally execute their plans on their desired large scale. ‘As in the near future, no new Russian prisoners-of-war can be expected,’ Himmler telegraphed Richard Glücks - chief of the SS department responsible for the camps - he would ‘deport a large number of Jews and Jewesses form Germany’ to the camps. ‘Make arrangements to house hundreds of thousands male Jews and a maximum of 50,000 female Jews in the camps during the next four weeks.’ This hastily planned deportation didn't take place. So short after the Wannsee Conference, they were insufficiently prepared for mass deportations. This also appears from an earlier message from Adolf Eichmann on January 31, 1942 to the Gestapo main offices in Germany. He indicated that ‘the recent evacuation of Jews from Germany to the east from separate parts of the Reich constitute the beginning of the Endlösung of the Jewish question in the Altreich, Austria and the Protektorat Bohemia and Moravia.’ However, he stressed immediately that these evacuations ‘would only be carried out in especially urgent cases.’ After all, work was still going on with new housing possibilities in order to send larger contingents of Jews across the border.

It didn't take long though before the extermination program was running at full steam. The first large deportation to the camps came from the General Government as Dr Joseph Bühler had wished at the Wannsee Conference. This extermination had been given the code name Aktion Reinhard and was carried out in Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka. The first trainload arrived in extermination camp Belzec on March 17, 1942. That same month, construction of camp Sobibor got off the ground, the first transports arriving in May. Treblinka was established in May and the first transport arrived on July 23, 1942. The same year, Jews from Lodz and other towns and villages in the Warthegau were deported to Chelmno. Deportations to Auschwitz-Birkenau had started in March 1942 and that year, transports from Poland, Slovakia, the Netherlands, Belgium, Yugoslavia and Theresienstadt reached the extermination camp. Deportation of West-European Jews had started in the summer of 1942. In the period from March 1942 to the middle of February 1943, half of the total number of Jews had been killed who wouldn't survive the war at the hands of the Nazis.

Jews from the Dutch transit camp Westerbork being deported. Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Despite the agreements at the conference, the Endlösung didn't proceed without problems. Heinrich Himmler and Adolf Eichmann had to intervene frequently. Problems mainly erupted when Jews, important for a war industry short of laborers, had to be deported as had been indicated at the conference by State secretary Erich Neumann of the Four Year Plan. When for instance Himmler gave the order on December 31, 1942 that all Jews from the General Government were to be ‘resettled’, the leadership of the Wehrmacht protested because it couldn't do without the Jewish forced laborers in their work shops. Himmler was compelled to keep certain workers alive and to transfer them to labor camps in Warsaw and Lublin where they, under the leadership of the SS-Wirtschafts- und Verwaltungshauptamt, the economic office of the SS, could continue their work for the Wehrmacht. At the end of the day however these Jews, temporarily exempted, were deported anyway because the aim of the SS was clear: in the end, Europe should be entirely Judenfrei.

Whereas the Endlösung progressed without problems in some countries, often in cooperation with local authorities or collaborating agencies, there also were countries where local authorities refused to cooperate. Deportation of the Italian Jews for instance started as late as the middle of September 1943. Although the Fascist government headed by dictator Benito Mussolini had introduced anti-Semitic legislation and had placed foreign Jews in camps, the Italians refused to cooperate with deportation. The Germans could only push through their plans when the northern part of the country was captured after the Italians had impeached Mussolini and surrendered to the Allies. In Hungary as well, deportations got under way much later than elsewhere in Europe. The country, headed by Miklos Horthy had joined the Axis powers in October 1940. Racial laws comparable to the Nuremberger Laws had been introduced but Horthy as well refused to cooperate with the deportations. These were only carried out when the Germans invaded the country in 1944, after signals had been intercepted indicating that Horthy wanted to denounce the alliance with Germany.

Despite the problems encountered in some countries and the difficult balance between the genocide project and the war industry, the SS eventually managed to murder an estimated total of 5,1 to 6 million Jews. Nearly half of them perished in concentration camps. Below is an overview of the estimated number of victims after the countries of origin according to the boundaries of 1937. The numbers are taken from historian Dieter Pohl:

- Poland 2,900,000 to 3,100,000

- Soviet-Union 950,000 to 1,050,000

- Hungary 270,000 to 300,000

- Romania 275,000 to 285,000

- Czechoslovakia 250,000 to 260,000

- Germany 160,000 to 165,000

- Lithuanian 140,000 to 150,000

- The Nederland 100,000 to 102,000

- France 76,000 to 77,000

- Latvia 65,000 to 70,000

- Austria 65,000

- Yugoslavia 60,000 to 65,000

- Greece 59,000

- Belgium 25,000

- Italy 6,000 to 7,000

- Luxemburg 1,200

- Estonia 1,000

- Norway 758

- Denmark 116

- Albania 100

- Total 5,600,000 to 5,700,000

Definitielijst

- Auschwitz-Birkenau

- The largest German concentration camp, located in Poland. Liberated on 26 January 1945. An estimated 1,1 million people, mainly Jews, perished here mainly in the gas chambers.

- Four Year Plan

- A German economic plan focussing at all sectors of the economy whereby established production goals had to be achieved in four years time.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Theresienstadt

- City in the Czech Republic. Here the Nazis established a model concentration camp.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Epilogue

Out of those present at the Wannsee Conference, at least five of them died before the end of May 1945, others were detained by the Allies and/or charged with war crimes.

- On June 4, 1942, Reinhard Heydrich succumbed in a hospital in Prague to injuries he had sustained during an attack on his life by Czech resistance fighter on May 27

- Roland Freisler lost his life in Berlin on February 3, 1945 in or near the Volksgerichtshof building during an Allied bombardment

- Rudolf Lange was killed in battle on February 23, 1945 near Posen in Poland. Shortly before, February 6, he was rewarded with the Deutsches Kreuz in Gold. According to some sources he didn't die in action but committed suicide

- Alfred Meyer was found dead on the bank of the river Wezer. Cause of death was suicide

- Heinrich Müller was last seen in Berlin on April 29, 1945. His fate is unknown but the most likely theory is that he died in Berlin in May 1945

- Martin Luther saw the end of the war in concentration camp Sachsenhausen following an argument with Außenminister Joachim von Ribbentrop. He died in May 1945, shortly after the liberation of the camp

- Karl Eberhart Schöngarth was charged with war crimes by a British tribunal after the war. He was sentenced to death on February 11, 1946 for having given the order to murder an American prisoner-of-war who had bailed out of his aircraft on November 21, 1944 near Enschede in the Netherlands and was arrested by the Gestapo. He was hanged on May 16, 1946 in Hameln prison

- Friedrich Kritzinger testified before the International Military Tribunal (IMT) he was ashamed of the Nazi crimes. He was released becasuse of his bad health and passed away on April 25, 1947

- Joseph Bühler was witness for Hans Frank during the IMT who was sentenced to death. Bühler was subsequently extradicted to Poland where he stood trial between April 17 and June 5, 1948 in Krakow. He was sentenced to death and executed in August 1948

- Erich Neumann was detained by the Allies in May 1945 but was released in early 1948 because of illness. He died the same year

- Wilhelm Stuckart was sentenced to 3 years and 10 months imprisonment but didn't have to serve his sentence because of his remand. Afterwards he was alderman of finance in Helmstedt and secretary of the Institute to Promote Economy in Lower Saxonia. From 1951 onwards, he was third Landesvorsitzende of the Union of Displaced and Dishonored. In 1953, a denazification court labeled him a Mittläufer and he was fined 50,000 German Mark. He died in a car accident on November 15, 1953

- Adolf Eichmann escaped to Argentina where he was arrested by Israeli secret agents on May 11, 1960 who abducted him to Israel. There he was charged with for instance crimes against the Jewish people and crimes against humanity. He was found guilty on all counts of the indictment and sentenced to death on December 15, 1961. He was hanged in Ramleh prison in the night of May 31 to June 1, 1962

- Georg Leibbrand was made a prisoner-of-war by the Allies and was imprisoned from 1945 to May 1949. Thereafter he worked for an American cultural institution in Munich. In 1950, a preliminary criminal investigation was launched against him into his role in the extermination of Jews, but the case was dropped in August 1950. He was released from prosecution and passed away in 1962

- Otto Hofmann was sentenced to 25 years in prison during the trial in Nuremberg against the Rasse und Siedlungshauptamt but was released in 1954. He worked as a clerc in Württemberg and passed away on December 31, 1982

- Gerhard Klopfer was interned after the war until 1949. He subsequently worked as a tax advisor and later as a lawyer. In 1962, he was released from prosecution by the Generalstaatsanwaltschaft in Ulm. He died there in February 1987

The villa in which the conference had been held was used by the Sicherheitsdienst throughout the war. It was the residence of numerous high ranking officers and from October 1944 onwards, it was used by SS-Gruppenführer Otto Ohlendorf, head of the Innenstelle of the SD as his HQ. After the capitulation, the building was in use by the Allies in 1945 and 1946. In 1947 and 1948 it housed a Volksschule and from 1952 to 1988 an educational center for pupils. From 1965 to 1972, historian Joseph Wulf (1912-1974) attempted to establish a documentation center of the Holocaust in it but to no avail. As late as 1992, exactly 50 years after the conference, a memorial and documentation center was opened in the villa. The permanent exposition on the Wannsee Conference and the Holcaust can be visited daily today.

Definitielijst

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- crimes against humanity

- Term that was introduced during the Nuremburg Trials. Crimes against humanity are inhuman treatment against civilian population and persecution on the basis of race or political or religious beliefs.

- denazification

- Post war policy of the allies in Germany to punish Nazi war criminals and to remove known Nazis from positions of power or public service.

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Wannsee Conference

- Conference at the Wannsee on 20 January 1942. The Nazi’s made final agreements about the extermination of Jews in Europe, the Final Solution (Ëndlösung).

- war crimes

- Crimes committed in wartime. Often concerning crimes committed by soldiers against civilians.

Information

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 15-11-2022

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- ARAD, Y., Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, Indiana University Press, Bloomington (USA), 1999.

- BREITMAN, R., Heinrich Himmler, Verbum, Laren, 2005.

- DEDERICHS, M.R., Heydrich, Fontaine Uitgevers, 's Graveland, 2007.

- EVANS, R.J., Het Derde Rijk deel 2, Spectrum, Utrecht, 2006.

- FRIEDLäNDER, S., Nazi-Duitsland en de Joden, Nieuw Amsterdam, Amsterdam, 2007.

- KERSHAW, I., Hitler - Vergelding 1936-1945, Het Spectrum, Utrecht, 2003.

- KNOPP, G., Hitlers Holocaust, Byblos, Amsterdam, 2001.

- MACLEAN, F., The Field Men, Shiffer Military History, Atglen (USA), 1999.

- POHL, D., Holocaust, Verbum, Laren, 2005.

- REES, L., Auschwitz, Anthos, Amsterdam, 2005.

- ROSEMAN, M., De villa, het meer, de conferentie, Balans, Amsterdam, 2002.

- SPECTOR, S. & ROZETT, R., Encyclopedie van de Holocaust, Kok, Kampen, 2004.

- WISTRICH, R.S., Who's who in Nazi Germany, Routledge, Londen, 2002.